Kawkab al-Hawa

Kawkab al-Hawa كوكب الهوا Kaukab al Hawa | |

|---|---|

The northwestern tower of Belvoir Fortress, outside which the village Kawkab al-Hawa expanded. | |

| Etymology: "star of the wind"[1] | |

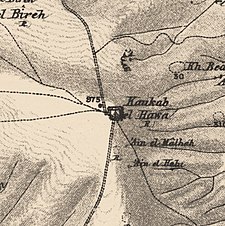

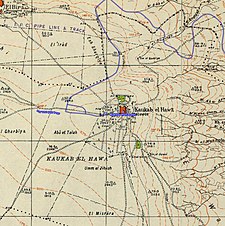

A series of historical maps of the area around Kawkab al-Hawa (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°35′43″N 35°31′12″E / 32.59528°N 35.52000°E | |

| Palestine grid | 199/222 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Baysan |

| Date of depopulation | 16 May 1948[4] |

| Area | |

• Total | 9,949 dunams (9.949 km2 or 3.841 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

• Total | 300[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Belvoir Castle |

Kawkab al-Hawa (Arabic: كوكب الهوا), is a depopulated former Palestinian village located 11 km north of Baysan. It was built within the ruins of the Crusader fortress of Belvoir, from which it expanded. The Crusader names for the Frankish settlement at Kawkab al-Hawa were Beauvoir, Belvoir, Bellum videre, Coquet, Cuschet and Coket.[5][6][7] During Operation Gideon in 1948, the village was occupied by the Golani Brigade and depopulated.[8]

History

Yaqut al-Hamawi, writing in the 1220s, referred to the place as a castle near Tiberias. According to him, it fell in ruins after the reign of Saladin.[9] The Ayyubid commander of Ajlun, Izz al-Din Usama, was given Kawkab al-Hawa as an iqta ("fief") by Saladin in the late 1180s and it remained in his hands until 1212, when it was seized by sultan al-Mu'azzam.[10][11]

An inscription in the Ustinow collection, dated, tentatively, to the 13th century, Ayyubid period, was found incised on a basalt rock near the spring at Kawkab al-Hawa. The inscription state: "He ordered to make this blessed fountain the illustrious amir, Shuja ad-Din, may his glory be perpetuated".[12]

Ottoman era

In 1517 the village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Kawkab al-Hawa belonged to Turabay Emirate (1517-1683), which encompassed also the Jezreel Valley, Haifa, Jenin, Beit She'an Valley, northern Jabal Nablus, Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, and the northern part of the Sharon plain.[13][14]

In 1596, Kawkab al-Hawa was administrated by nahiya ("subdistrict") of Shafa under the liwa' ("district") of Lajjun. It had a population of 9 Muslim households, an estimated 50 persons. The villagers paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat, beans and melons, as well as on vineyards; a total of 4,500 akçe.[15]

Pierre Jacotin named the village Kaoukab on his map from 1799.[16] The scholar Edward Robinson described the place in 1838 as a small village ("Kaukab el-Hawa"), situated "on the brow of the Jordan Valley", and he identified the place as the former Belvoir fortress.[5]

In 1870/1871 (1288 AH), an Ottoman census listed the village in the nahiya (sub-district) of Shafa al-Shamali.[17]

Victor Guérin visited in 1875, and found some families using the vaulted spaces still standing inside the fortress.[18]

Since the village was built within the outlines of the fortress of Belvoir, it was slow to expand. The villagers, who numbered about 110 in 1859, resided within the fortress walls and cultivated about 13 faddans outside them.[19]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the Mandatory Palestine authorities, Kukab had a population of 167, all Muslims,[20] increasing in the 1931 census to 220, still all Muslims, in 46 houses.[21]

In time the village expanded to the north and the west in a circle around the fortress. The Muslim population of the village used their land, which lay outside the village walls, for agriculture.[22]

In the 1945 statistics Kawkab al-Hawa had a population of 300 Muslims[2] with a total of 9,949 dunes of land.[3] Of this, a total of 5,839 dunums was allocated to cereals; 170 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[23][22] while 56 dunams was built-up land.[24]

1948 War and aftermath

According to Benny Morris, Kibbutzniks demanded – and often themselves carried out – the destruction of neighbouring villages as a means of blocking the return of the Arab villagers. For this reason a veteran local leader, Nahum Hurwitz of Kfar Gil'adi appealed in a letter in September 1948 for permission to destroy Kawkab al-Hawa, Jabbul, al-Bira and al-Hamidiyya in the area for fear that they may be used by Arabs for military operations and to enable them to "take the village's lands, because the Arabs won't be able to return there".[25]

Walid Khalidi described the remaining structures of the village in 1992:

"The village has been eliminated, but the site of the Belvoir Castle has been excavated and turned into a tourist attraction. Fig and olive trees grow on the village site. The slopes overlooking the Baysan Valley and Wadi al-Bira are used by Israelis as grazing areas; they also cultivate the other surrounding lands."[22]

According to Meron Benvenisti, Kawkab al-Hawa represents one of the most conspicuous examples of the Israeli practice of removing Arab settlements of all Arab structures which did not interest them. At Kawkab al-Hawa (and at Caesarea) all Arab structures (except those useful as tourist amenities) were demolished by the Israelis, while the Crusader buildings were restored and made into tourist attractions. According to Benvenisti: "In the Israeli context, it is preferable to immortalize those who exterminated the Jewish communities of Europe (in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries) and murdered the Jews of Jerusalem in 1099 than to preserve relics of the local Arab civilization with which today's Israelis coexist. Crusader structures, both authentic and fabricated, lend a European, romantic character to the country's landscape, whereas Arab buildings spoil the myth of an occupied land under foreign rule, awaiting liberation at the hands of the Jews returning to their homeland."[26]

See also

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p.162

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 6

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 43

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village # 115

- ^ a b Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 226

- ^ Stubbs and Hassall, 1902, p. 329

- ^ Ellenblum, 2003, p. 56

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 260

- ^ Mu'jam Al-Buldan, cited in Le Strange, 1890, p.483. Also quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p.53.

- ^ Humphreys, 1977, p. 144

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, pp. 117-119

- ^ Sharon, 2007, pp. 131-134

- ^ al-Bakhīt, Muḥammad ʻAdnān; al-Ḥamūd, Nūfān Rajā (1989). "Daftar mufaṣṣal nāḥiyat Marj Banī ʻĀmir wa-tawābiʻihā wa-lawāḥiqihā allatī kānat fī taṣarruf al-Amīr Ṭarah Bāy sanat 945 ah". www.worldcat.org. Amman: Jordanian University. pp. 1–35. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Marom, Tepper; Adams, Matthew, J (2023). "Lajjun: Forgotten Provincial Capital in Ottoman Palestine". Levant. 55 (2): 218–241. doi:10.1080/00758914.2023.2202484. S2CID 258602184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 157. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 53

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 169 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grossman, David (2004). Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. p. 256.

- ^ Guérin, 1880, pp. 129-132

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 85, Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 53.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table IX, p. 31

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 79

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p. 53

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 85

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 135

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 357. Quotes from Peterzil to Erem, Bentov, Hazan and Cisling (August 10, 1948), quoting an extract from an undated letter from Faivel Cohen of Ma'ayan Barukh, to Peterzil, HHA-ACP 10.95.10(5)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) therein. - ^ Benvenisti, 2001, pp. 169, 303

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2001). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Conder, C.R. (1874). "Lieut. Claude R. Conder´s reports". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 6: 178–187. (Conder, 1874, pp. 179-180)

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Ellenblum, R. (2003). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52187-1.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Humphreys, R.S. (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193-1260. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-263-7.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp. 177, 219)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray. (pp. 310, 314, 329, 339)

- Sharon, M. (2007). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Addendum. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15780-4.

- Stubbs, W.; Hassall, Arthur, eds. (1902). Historical Introductions to the Rolls Series. London, New York: Longmans, Green, and co.

External links

- Welcome to Kawkab-al-Hawa

- Kawkab al-Hawa, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 9: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Kawkab al-Hawa, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Kawkab Al-Hawa photos from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh