Kara Sea

| Kara Sea | |

|---|---|

Map showing the location of the Kara Sea. | |

| Location | Arctic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 77°N 77°E / 77°N 77°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Russia |

| Surface area | 926,000 km2 (358,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 131 m (430 ft) |

| Water volume | 121,000 km3 (98×109 acre⋅ft) |

| Frozen | Practically all year round |

| References | [1] |

The Kara Sea[a] is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all extensions of the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia.

The Kara Sea's northern limit is marked geographically by a line running from Cape Kohlsaat in Graham Bell Island, Franz Josef Land, to Cape Molotov (Arctic Cape), the northernmost point of Komsomolets Island in Severnaya Zemlya.

The Kara Sea is roughly 1,450 km (900 mi) long and 970 km (600 mi) wide with an area of around 880,000 km2 (339,770 sq mi) and a mean depth of 110 metres (360 ft).

Its main ports are Novy Port and Dikson and it is important as a fishing ground although the sea is ice-bound for all but two months of the year. The Kara Sea contains the East-Prinovozemelsky field (an extension of the West Siberian Oil Basin), containing significant undeveloped petroleum and natural gas. In 2014, US government sanctions resulted in Exxon having until 26 September to discontinue its operations in the Kara Sea.[2]

Name origin

It is named after the Kara river (flowing into Baydaratskaya Bay), which is now relatively insignificant but which played an important role in the Russian conquest of northern Siberia.[3] The Kara river name is derived from a Nenets word meaning 'hummocked ice'.[4]

Geography

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Kara Sea as follows:[5]

- On the West. The Eastern limit of Barents Sea [Cape Kohlsaat to Cape Zhelaniya (Desire); West and Southwest coast of Novaya Zemlya to Cape Kussov Noss and thence to Western entrance Cape, Dolgaya Bay (70°15′N 58°25′E / 70.250°N 58.417°E) on Vaigach Island. Through Vaigach Island to Cape Greben; thence to Cape Belyi Noss on the mainland].

- On the North. Cape Kohlsaat to Cape Molotov (81°16′N 93°43′E / 81.267°N 93.717°E) (Northern extremity of Severnaya Zemlya on Komsomolets Island).

- On the East. Komsomolets Island from Cape Molotov to South Eastern Cape; thence to Cape Vorochilov, Oktiabrskaya Revolutziya Island to Cape Anuchin. Then to Cape Unslicht on Bolshevik Island. Bolshevik Island to Cape Yevgenov. Thence to Cape Pronchisthehev on the main land (see Russian chart No. 1484 of the year 1935).

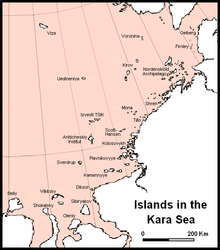

Islands

There are many islands and island groups in the Kara Sea. Unlike the other marginal seas of the Arctic, where most islands lie along the coasts, in the Kara Sea many islands, like the Arkticheskiy Institut Islands, the Izvesti Tsik Islands, the Kirov Islands, Uedineniya or Lonely Island, Wiese Island, and Voronina Island are located in the open sea of its central regions.

The largest group in the Kara Sea is by far the Nordenskiöld Archipelago, with five large subgroups and over ninety islands. Other important islands in the Kara Sea are Bely Island, Dikson Island, Taymyr Island, the Kamennyye Islands and Oleni Island. Despite the high latitude, all islands are unglaciated except for Ushakov Island at the extreme northern limit of the Kara Sea.[6]

Current patterns

Water circulation patterns in the Kara Sea are complex. The Kara Sea tends to be sea ice covered between September and May,[7] and between May and August heavily influenced by freshwater run-off (roughly 1200 km3 yr−1[8]) from the Russian rivers (e.g., Ob, Yenisei, Pyasina, Pur, and Taz). The Kara Sea is also affected by the water inflow from the Barents Sea, which brings 0.6 Sv in August and 2.6 Sv in December.[9] The advected water originates from the Atlantic, but it was cooled and mixed with freshwater in the Barents Sea before it reaches the Kara Sea.[7] Simulations with the Hamburg shelf ocean model (HAMSOM) suggest that no typical water current pattern consists in the Kara Sea throughout the year. Depending on the freshwater run-off, the dominant wind patterns, and the sea ice formation, the water currents change.[7]

Connections to global weather

Barents Sea is the fastest-warming part of the Arctic, and some assessments now treat Barents sea ice as a separate tipping point from the rest of the Arctic sea ice, suggesting that it could permanently disappear once the global warming exceeds 1.5 degrees.[10] This rapid warming also makes it easier to detect any potential connections between the state of sea ice and weather conditions elsewhere than in any other area. The first study proposing a connection between floating ice decline in the Barents Sea and the neighbouring Kara Sea and more intense winters in Europe was published in 2010,[11] and there has been extensive research into this subject since then. For instance, a 2019 paper holds BKS ice decline responsible for 44% of the 1995–2014 central Eurasian cooling trend, far more than indicated by the models,[12] while another study from that year suggests that the decline in BKS ice reduces snow cover in the North Eurasia but increases it in central Europe.[13] There are also potential links to summer precipitation:[14] a connection has been proposed between the reduced BKS ice extent in November–December and greater June rainfall over South China.[15] One paper even identified a connection between Kara Sea ice extent and the ice cover of Lake Qinghai on the Tibetan Plateau.[16]

However, BKS ice research is often subject to the same uncertainty as the broader research into Arctic amplification/whole-Arctic sea ice loss and the jet stream, and is often challenged by the same data.[17] Nevertheless, the most recent research still finds connections which are statistically robust,[18] yet non-linear in nature: two separate studies published in 2021 indicate that while autumn BKS ice loss results in cooler Eurasian winters, ice loss during winter makes Eurasian winters warmer:[19] as BKS ice loss accelerates, the risk of more severe Eurasian winter extremes diminishes while heatwave risk in the spring and summer is magnified.[17][20]History

The Kara Sea was formerly known as Oceanus Scythicus or Mare Glaciale and it appears with these names in 16th century maps. Since it is closed by ice most of the year it remained largely unexplored until the late nineteenth century.

In 1556 Stephen Borough sailed in the Searchthrift to try to reach the Ob River, but he was stopped by ice and fog at the entrance to the Kara Sea. Not until 1580 did another English expedition, under Arthur Pet and Charles Jackman, attempt its passage. They too failed to penetrate it, and England lost interest in searching for the Northeast Passage.

In 1736–1737 Russian Admiral Stepan Malygin undertook a voyage from Dolgy Island in the Barents Sea. The two ships in this early expedition were the Perviy, under Malygin's command and the Vtoroy under Captain A. Skuratov. After entering the little-explored Kara Sea, they sailed to the mouth of the Ob River. Malygin took careful observations of these hitherto almost unknown areas of the Russian Arctic coastline. With this knowledge he was able to draw the first somewhat accurate map of the Arctic shores between the Pechora River and the Ob River.

In 1878, Finnish explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld on ship Vega sailed across the Kara Sea from Gothenburg, along the coast of Siberia, and despite the ice packs, got to 180° longitude by early September. Frozen in for the winter in the Chukchi Sea, Nordenskiöld waited and bartered with the local Chukchi people. The following July, the Vega was freed from the ice, and continued to Yokohama, Japan. He became the first to force the Northeast Passage. The largest group of islands in the Kara Sea, the Nordenskiöld Archipelago, has been named in his honour. The year 1912 was a tragic one for Russian explorers in the Kara Sea. In that fateful year unbroken consolidated ice blocked the way for the Northern Sea Route and three expeditions that had to cross the Kara Sea became trapped and failed: Sedov's on vessel St. Foka, Brusilov's on the St. Anna, and Rusanov's on the Gercules. Georgy Sedov intended to reach Franz Josef Land on ship, leave a depot over there, and sledge to the pole. Due to the heavy ice the vessel could only reach Novaya Zemlya the first summer and wintered in Franz Josef Land. In February 1914 Sedov headed to the North Pole with two sailors and three sledges, but he fell ill and died on Rudolf Island. Georgy Brusilov attempted to navigate the Northeast Passage, was trapped in the Kara Sea, and drifted northward for more than two years reaching latitude 83° 17' N. Thirteen men, headed by Valerian Albanov, left the vessel and started across the ice to Franz Josef Land, but only Albanov and one sailor (Alexander Konrad) survived after a gruesome three-month ordeal. The survivors brought the ship log of St. Anna, the map of her drift, and daily meteorological records, but the destiny of those who stayed on board remains unknown. In the same year the expedition of Vladimir Rusanov was lost in the Kara Sea. The prolonged absence of those three expeditions stirred public attention, and a few small rescue expeditions were launched, including Jan Nagórski's five air flights over the sea and ice from the NW coast of Novaya Zemlya.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the scale and scope of exploration of the Kara Sea increased greatly as part of the work of developing the Northern Sea Route. Polar stations, of which five already existed in 1917, increased in number, providing meteorologic, ice reconnaissance, and radio facilities. By 1932 there were 24 stations, by 1948 about 80, and by the 1970s more than 100. The use of icebreakers and, later, aircraft as platforms for scientific work were developed. In 1929 and 1930 the Icebreaker Sedov carried groups of scientists to Severnaya Zemlya, the last major piece of unsurveyed territory in the Soviet Arctic; the archipelago was completely mapped under Georgy Ushakov between 1930 and 1932.

Particularly worth noting are three cruises of the Icebreaker Sadko, which went farther north than most; in 1935 and 1936 the last unexplored areas in the northern Kara Sea were examined and the small and elusive Ushakov Island was discovered.

In the summer of 1942, German Kriegsmarine warships and submarines entered the Kara Sea to destroy as many Russian vessels as possible. This naval campaign was named "Operation Wunderland". Its success was limited by the presence of ice floes, as well as bad weather and fog. These effectively protected the Soviet ships, preventing the damage that could have been inflicted on the Soviet fleet under fair weather conditions.

In October 2010, the Russian government awarded a license to Russian oil company Rosneft for developing the East-Prinovozemelsky oil and gas structure in the Kara Sea.[21][22]

Nuclear dumping

There is concern about radioactive contamination from nuclear waste the former Soviet Union dumped in the sea and the effect this will have on the marine environment. According to an official "White Paper" report compiled and released by the Russian government in March 1993, the Soviet Union dumped six nuclear submarine reactors and ten nuclear reactors into the Kara Sea between 1965 and 1988.[23] Solid high- and low-level wastes unloaded from Northern Fleet nuclear submarines during reactor refuelings were dumped in the Kara Sea, mainly in the shallow fjords of Novaya Zemlya, where the depths of the dumping sites range from 12 to 135 meters, and in the Novaya Zemlya Trough at depths of up to 380 meters. Liquid low-level wastes were released in the open Barents and Kara Seas. A subsequent appraisal by the International Atomic Energy Agency showed that releases are low and localized from the 16 naval reactors (reported by the IAEA as having come from seven submarines and the icebreaker Lenin) which were dumped at five sites in the Kara Sea. Most of the dumped reactors had suffered an accident.[24]

The Soviet submarine K-27 was scuttled in Stepovogo Bay with its two reactors filled with spent nuclear fuel.[25] At a seminar in February 2012 it was revealed that the reactors on board the submarine could re-achieve criticality and explode (a buildup of heat leading to a steam explosion vs. nuclear). The catalogue of waste dumped at sea by the Soviets, according to documents seen by Bellona, includes some 17,000 containers of radioactive waste, 19 ships containing radioactive waste, 14 nuclear reactors, including five that still contain spent nuclear fuel; 735 other pieces of radioactively contaminated heavy machinery, and the K-27 nuclear submarine with its two reactors loaded with nuclear fuel.[26]

Nature reserve

The Great Arctic State Nature Reserve—the largest nature reserve of Russia—was founded on 11 May 1993, by Resolution No. 431 of the Government of the Russian Federation (RF). The Kara Sea Islands section (4,000 km2) of the Great Arctic Nature Reserve includes: the Sergei Kirov Archipelago, the Voronina Island, the Izvestiy TSIK Islands, the Arctic Institute Islands, the Svordrup Island, Uedineniya (Ensomheden) and a number of smaller islands. This section represents rather fully the natural and biological diversity of Arctic sea islands of the eastern part of the Kara Sea.

Nearby, the Franz Josef Land and Severny Island in northern Novaya Zemlya are also registered as a sanctuary, the Russian Arctic National Park.

See also

- Valerian Albanov

- List of seas

- Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

- Northern Sea Route

- Boris Vilkitsky

- West Siberian petroleum basin

Notes

References

- ^ Stein, R. (2008). Arctic Ocean Sediments: Processes, Proxies, and Paleoenvironment. Elsevier. p. 37. ISBN 9780080558851.

- ^ "Sanksjoner kan avslutte boring i Karahavet" [Sanctions could end drilling in the Kara Sea]. DN (in Norwegian). 16 September 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Pospelov, E.M. (1998). Geograficheskie nazvaniya mira [Geographic names of the world] (in Russian). Moscow. p. 191.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vize, V.Yu. (1939). Karskoye more // Morya Sovetskoy Arktiki: Ocherki po istorii issledovaniya [Kara Sea // Seas of the Soviet Arctic: Essays on the history of research] (in Russian). Leningrad. pp. 180–217.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Arctic Glaciers; Ushakov Island

- ^ a b c Harms, I. H.; Karcher, M. J. (15 June 1999). "Modeling the seasonal variability of hydrography and circulation in the Kara Sea" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 104 (C6): 13431–13448. Bibcode:1999JGR...10413431H. doi:10.1029/1999JC900048.

- ^ Pavlov, V.K.; Pfirman, S.L. (1995). "Hydrographic structure and variability of the Kara Sea: Implications for pollutant distribution". Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 42 (6): 1369–1390. Bibcode:1995DSRII..42.1369P. doi:10.1016/0967-0645(95)00046-1.

- ^ Schauer, Ursula; Loeng, Harald; Rudels, Bert; Ozhigin, Vladimir K; Dieck, Wolfgang (2002). "Atlantic Water flow through the Barents and Kara Seas". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 49 (12): 2281–2298. Bibcode:2002DSRI...49.2281S. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00125-5.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Petoukhov, Vladimir; Semenov, Vladimir A. (2010). "A link between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D21): D21111. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11521111P. doi:10.1029/2009JD013568.

- ^ Mori, Masato; Kosaka, Yu; Watanabe, Masahiro; Nakamura, Hisashi; Kimoto, Masahide (14 January 2019). "A reconciled estimate of the influence of Arctic sea-ice loss on recent Eurasian cooling". Nature Climate Change. 9 (2): 123–129. Bibcode:2019NatCC...9..123M. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0379-3. S2CID 92214293.

- ^ Xu, Bei; Chen, Haishan; Gao, Chujie; Zhou, Botao; Sun, Shanlei; Zhu, Siguang (1 July 2019). "Regional response of winter snow cover over the Northern Eurasia to late autumn Arctic sea ice and associated mechanism". Atmospheric Research. 222: 100–113. Bibcode:2019AtmRe.222..100X. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2019.02.010. S2CID 126675127.

- ^ He, Shengping; Gao, Yongqi; Furevik, Tore; Wang, Huijun; Li, Fei (16 December 2017). "Teleconnection between sea ice in the Barents Sea in June and the Silk Road, Pacific–Japan and East Asian rainfall patterns in August". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 35: 52–64. doi:10.1007/s00376-017-7029-y. S2CID 125312203.

- ^ Yang, Huidi; Rao, Jian; Chen, Haishan (25 April 2022). "Possible Lagged Impact of the Arctic Sea Ice in Barents–Kara Seas on June Precipitation in Eastern China". Frontiers in Earth Science. 10: 886192. Bibcode:2022FrEaS..10.6192Y. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.886192.

- ^ Liu, Yong; Chen, Huopo; Wang, Huijun; Sun, Jianqi; Li, Hua; Qiu, Yubao (1 May 2019). "Modulation of the Kara Sea Ice Variation on the Ice Freeze-Up Time in Lake Qinghai". Journal of Climate. 32 (9): 2553–2568. Bibcode:2019JCli...32.2553L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0636.1. S2CID 133858619.

- ^ a b Song, Mirong; Wang, Zhao-Yin; Zhu, Zhu; Liu, Ji-Ping (August 2021). "Nonlinear changes in cold spell and heat wave arising from Arctic sea-ice loss". Advances in Climate Change Research. 12 (4): 553–562. Bibcode:2021ACCR...12..553S. doi:10.1016/j.accre.2021.08.003. S2CID 238716298.

- ^ Dai, Aiguo; Deng, Jiechun (4 January 2022). "Recent Eurasian winter cooling partly caused by internal multidecadal variability amplified by Arctic sea ice-air interactions". Climate Dynamics. 58 (11–12): 3261–3277. Bibcode:2022ClDy...58.3261D. doi:10.1007/s00382-021-06095-y. S2CID 245672460.

- ^ Zhang, Ruonan; Screen, James A. (16 June 2021). "Diverse Eurasian Winter Temperature Responses to Barents-Kara Sea Ice Anomalies of Different Magnitudes and Seasonality". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (13). Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4892726Z. doi:10.1029/2021GL092726. S2CID 236235248.

- ^ Sun, Jianqi; Liu, Sichang; Cohen, Judah; Yu, Shui (2 August 2022). "Influence and prediction value of Arctic sea ice for spring Eurasian extreme heat events". Communications Earth & Environment. 3 (1): 172. Bibcode:2022ComEE...3..172S. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00503-9. S2CID 251230011.

- ^ "Rosneft and Gazprom clinch Arctic acreage". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 15 October 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "BP and Rosneft in exploration pact". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 14 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Radioecological Hazard of Ship Nuclear Reactors Sunken in the Arctic", Atomic Energy, Vol.79, No. 3, 1995.

- ^ Mount, M.E., Sheaffer, M.K. and Abbott, D.T. (1994). "Kara Sea radionuclide inventory from naval reactor disposal". J. Environ. Radioactivity, 25, 1–19.

- ^ "Lifting Russia's accident reactors from the Arctic seafloor will cost nearly €300 million". The Barents Observer. 8 March 2020.

- ^ Charles Digges (28 August 2012). "Russia announces enormous finds of radioactive waste and nuclear reactors in Arctic seas". Bellona. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

External links

- International Atomic Energy Agency:Radiological Conditions of the Western Kara Sea Archived 27 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- J. Zeeberg. Into the Ice Sea.

- Sea ice and polynias in the Kara Sea: [1] & [2]

- Marine pollution in the Kara Sea: [3]

- Ecological assessment at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 30 September 2006)

- "Russians Describe Extensive Dumping of Nuclear Waste", The New York Times, 27 April 1993