Cape Crozier

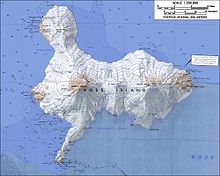

Cape Crozier (77°31′S 169°24′E / 77.517°S 169.400°E) is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's polar expedition of 1839 to 1843 with HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and was named after Commander Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror, one of the two ships of Ross' expedition.[1]

The extinct volcano Mount Terror, also named during the Ross expedition, rises sharply from the Cape to a height of 3,230 m (10,600 ft),[2] and the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf (formerly known as the Barrier or Great Ice Barrier) stretches away to its east.

History

First landing, 1902

The first landing at Cape Crozier was on 22 January 1902, during Captain Scott's Discovery Expedition. A party from RRS Discovery landed by small boat on a stony beach area a little to the west of the Cape. Scott, Edward Wilson and Charles Royds climbed the slope to a vantage point from which they could view the Barrier surface, and they were also able to observe the large Adelie penguin colony which inhabited the surrounding ice-free terrain.

- Historic site

A message box was erected that day, prominently marked, for messages to be collected by any future relief ship. At the time it held a metal message cylinder, which has since been removed. The site has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 69), following a proposal by New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[3]

Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13

Captain Scott seriously considered Cape Crozier as the base for his second Antarctic expedition.[4] On the previous trip, the Discovery had been frozen into its McMurdo Sound berth for nearly two years, and had barely escaped in February 1904, a circumstance that had led to an expensive relief operation and some opprobrium for Scott. There would be no chance of the Terra Nova being icebound in the open seas off Cape Crozier, but the unsheltered location would make landings of stores and personnel difficult, the shore base would be at the mercy of rough weather, and the land route to the Barrier surface was problematic. Scott decided to return to McMurdo Sound for his base, though to a more northerly anchorage (Cape Evans).

Winter journey, 1911

Wilson was keen to continue researching the emperor penguin embryo, and needed to obtain eggs at an early stage of incubation, which meant collecting them in the depth of the Antarctic winter. In the Zoology section of the Discovery Expedition's published Scientific Report he suggested a plan for a "winter journey" whereby these eggs could be retrieved.[5] This journey, with Captain Scott's approval,[6] was undertaken between 27 June and 2 August 1911, by Wilson, Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Henry Robertson Bowers. Cherry-Garrard later described the trek in his book, The Worst Journey in the World. In the winter darkness and extreme weather conditions the journey proved slow and hazardous, but despite mishaps three eggs were retrieved and later presented by Cherry-Garrard to the Natural History Museum.[7] Ultimately, however, their scientific value proved minimal.[8] The remains of a stone hut, constructed in July 1911 by Wilson's winter journey party, have been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 21), following a proposal by New Zealand to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[9]

Restricted site

Cape Crozier is within a restricted area and permission is required to visit it. Cape Crozier is home to one of the largest Adélie penguin colonies in the world (~270,000 breeding pairs as of 2012),[10] one of the two southernmost emperor penguin colonies (>1900 breeding pairs as of 2018),[11] and one of the largest south polar skua colonies in the world (~1,000 breeding pairs).[12] It also hosts several species of lichens, including at least three not previously found in this part of Antarctica.[13] It has been designated an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA 124),[14] and designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International.[15] From 2001 to 2005, two enormous icebergs known as Iceberg B-15 and C16 were present near shore and affected the Adelie and Emperor penguin colonies.[16][17]

Named features

Named features around Cape Crozier include Wood Point, Williamson Rock, Post Office Hill, Topping Cone, The Knoll, Kyle Cone, Bomb Peak and Igloo Spur.[18]

Wood Point

77°25′S 168°57′E / 77.417°S 168.950°E. A point on the north coast of Ross Island, 10 nautical miles (19 km; 12 mi) east-southeast of Cape Tennyson. Named by the United States Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) in 1964 for Robert C. Wood, United States Antarctic Research Program (USARP) biologist who carried on investigations at nearby Cape Crozier in the summer seasons 1961-62, 1962–63, and 1963–64.[19]

Williamson Rock

77°27′S 169°15′E / 77.450°S 169.250°E. A rock lying 4 nautical miles (7.4 km; 4.6 mi) northwest of Cape Crozier, close off the north coast of Ross Island. Charted by the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910–13, under Scott. Named for Thomas S. Williamson, who as able seaman and petty officer accompanied Scott's expeditions of 1901-04 and 1910-13.[20]

Igloo Spur

77°33′S 169°16′E / 77.550°S 169.267°E. A small, isolated spur 160 metres (520 ft) high high at the culmination of the general ridge extending southeast from Bomb Peak. Mapped and so named by the NZGSAE, 1958–59, because it was on this feature that Doctor E.A. Wilson and his party built a stone igloo during the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910-13.[21]

Kaminuma Bluff

77°36′S 168°57′E / 77.6°S 168.95°E. A bold ice-covered bluff that rises to over 200 metres (660 ft) high near the shore in southeast Ross Island. The bluff is midway between Cape Mackay and Cape Crozier. At the suggestion of P.R. Kyle, named by Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) (2000) after Katsutada Kaminuma, National Institute of Polar Research, Japan, who was a founding member of the International Mount Erebus Seismic Study (IMESS), 1980-81 through 1986. This was a joint project with the United States, Japan, and New Zealand. Kaminuma was the lead Japanese member and continued to work in Antarctica and on Mount Erebus for many years.[22]

References

- ^ Alberts 1995, p. 164.

- ^ Edward Wilson's Discovery diary: Map p290 estimates height @ 10,775 ft

- ^ "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ Scott's Last Expedition Vol 1 pp17-18

- ^ Seaver, pp 247-48

- ^ Scott's Last Expedition, Vol 1 p334

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, Worst Journey pp351-53

- ^ "Discover | Natural History Museum". Nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

- ^ "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

- ^ Lyver, P. O.; Barron, M.; Barton, K. J.; Ainley, D. G.; Pollard, A.; Gordon, S.; McNeill, S.; Ballard, G.; Wilson, P. R. (2014). "Trends in the Breeding Population of Adelie Penguins in the Ross Sea, 1981-2012: A Coincidence of Climate and Resource Extraction Effects". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e91188. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091188. PMC 3951313. PMID 24621601.

- ^ Schmidt, Annie E.; Ballard, Grant (2020). "Significant chick loss after early fast ice breakup at a high-latitude emperor penguin colony". Antarctic Science. 32 (3): 180–185. Bibcode:2020AntSc..32..180S. doi:10.1017/S0954102020000048. S2CID 213566527.

- ^ "SCAR Bulletin". Scar.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

- ^ "Additions to the lichen flora of Victoria Land, Antarctica". Polish Polar Research. 2011. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- ^ "Cape Crozier, Ross Island" (PDF). Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 124: Measure 7, Annex. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2008. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- ^ "Cape Crozier". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Kooyman, Gerald L.; Ainley, David G.; Ballard, Grant; Ponganis, Paul. J. (2007). "Effects of giant icebergs on two emperor penguin colonies in the Ross Sea, Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 19 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1017/S0954102007000065.

- ^ Shepherd, L.D.; Millar, C.D.; Ballard, G.; Ainley, D.G.; Wilson, P.R.; Haynes, G.D.; Baroni, C.; Lambert, D.M. (2005). "Microevolution and mega-icebergs in the Antarctic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (46): 16717–16722. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502281102. PMC 1283793.

- ^ Ross Island USGS.

- ^ Alberts 1995, p. 822.

- ^ Alberts 1995, p. 816.

- ^ Alberts 1995, p. 359.

- ^ Kaminuma Bluff USGS.

Sources

- Alberts, Fred G., ed. (1995), Geographic Names of the Antarctic (PDF) (2 ed.), United States Board on Geographic Names, retrieved 2024-01-30

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Board on Geographic Names.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Board on Geographic Names. - "Kaminuma Bluff", Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior

- Ross Island, USGS: United States Geological Survey, retrieved 2024-01-30

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

Bibliography

- Edward Wilson: Diary of the Discovery Expedition, Blandford Press 1966

- Scott's Last Expedition Vol 1, Smith, Elder & Co 1913

- Apsley Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Penguin Travel Library edition 1983

- George Seaver: Edward Wilson of the Antarctic, John Murray 1940 edition