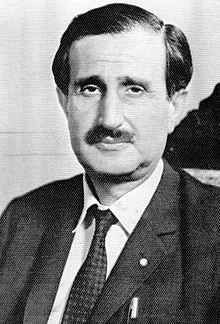

Kamal Jumblatt

Kamal Jumblatt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

كمال جنبلاط | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Progressive Socialist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 May 1949 – 16 March 1977 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Post established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Walid Jumblatt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 6 December 1917 Moukhtara, Chouf, Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon, Ottoman Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 March 1977 (aged 59) Baakleen, Chouf, Mount Lebanon, Lebanon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manner of death | Assassination by gunshots | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Mukhtara Palace | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Progressive Socialist Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | May Arslan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Walid Jumblatt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Nazira, Fouad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | St. Joseph University Sorbonne University Lebanese University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kamal Fouad Jumblatt (Arabic: كمال فؤاد جنبلاط; 6 December 1917 – 16 March 1977) was a Lebanese politician who founded the Progressive Socialist Party. He led the National Movement during the Lebanese Civil War. He was a major ally of the Palestine Liberation Organization until his assassination in 1977.[1] He authored more than 40 books centred on various political, philosophical, literary, religious, medical, social, and economic topics.[2] In September 1972, Kamal Jumblatt received the International Lenin Peace Prize.[3] He is the father of the Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt and the son-in-law of the Arab writer and politician Shakib Arslan.

Early life and education

Kamal Jumblatt was born on 6 December 1917 in Moukhtara.[note 1] He was born into the Jumblatt family, a prestigious family originally from present-day Syria, whose members were traditional leaders of the Lebanese Druze community. His father Fouad Joumblatt, the powerful Druze chieftain and director of the Chouf District, was murdered in an ambush on 6 August 1921.[5][6] Kamal was just four years old when his father was killed.[7][5] After his father’s death, his mother Nazira played a significant political role in the Druze community during the following two decades.[8]

In 1926, Kamal Jumblatt joined the Lazarus Fathers Institute in Aintoura, where he completed his elementary studies in 1928. He achieved his high school diploma, having studied French, Arabic, science and literature, in 1936, and a philosophy diploma in 1937.

Jumblatt then pursued higher studies in France, where he attended the Faculty of Arts at the Sorbonne University and obtained a degree in psychology and civil education, and another one in sociology. He returned to Lebanon in 1939, after the outbreak of World War II and continued his studies at Saint Joseph University where he obtained a law degree in 1945.

Early political career

Kamal Jumblatt practised law in Lebanon from 1941 to 1942 and was designated the Official State Lawyer for the Lebanese Government. In 1943, at the young age of twenty-six years and following the unexpected death of Hikmat Joumblatt, he became the leader of the Jumblatt clan, bringing him into the Lebanese political scene.[8] Despite his influential political role, throughout his career, he was in a rivalry over the political leadership over the Lebanese Druze with Majid Arslan.[9] Arslan was often preferred to represent the Druze faction and the longest serving Minister in Lebanese politics and served 22 terms as the Lebanese Defense Minister.[9] In September 1943 Kamal Jumblatt was elected to the National Assembly for the first time,[10] as a deputy of Mount Lebanon. He joined the National Bloc led by Émile Eddé, thus opposing the rule of the Constitutional Bloc, headed by the then-President, Bechara El Khoury. On 8 November 1943, however, he signed the constitutional amendment (which abolished the articles referring to the Mandate) demanded by the Constitutional Bloc. On 14 December 1946, he was appointed minister for the first time, for the portfolio of economy, in Riad Al Solh's cabinet.[11] His term was from 14 December 1946 to 7 June 1947, and he replaced Saadi Al Munla.[11] Sleiman Nawfal replaced Jumblatt as economy minister.[11]

In 1947, in spite of his own election for the second time as deputy, he thought of resigning from the government. He began to believe that change through the Lebanese political system was impossible.

Kamal Jumblatt officially founded the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) on 1 May 1949.[12] The PSP was a socialist party espousing secularism and officially opposed to the sectarian character of Lebanese politics. In practice, it has been led and largely supported since its foundation by various segments of Lebanese society, especially members of the Druze community, and the Jumblatt clan in particular. In 1949, Jumblatt firmly opposed the execution of political leader Antoun Saadeh and held the government responsible for his assassination. In the name of the PSP, Jumblatt called the first convention of the Arab Socialist Parties, which was held in Beirut in May 1951. Prior to the 1952 elections, Jumblatt declared the formation of the opposition salvation front electoral list in a rally on 18 March 1951 in the village of Barouk, Mount Lebanon. Clashes between Jumblatt's supporters and Lebanese security forces led to the death of four, three of them were PSP supporters. After this incident, he gave his famous speech: "Today, our party was baptized with blood". In the same year, he was re-elected for the third time as Deputy of Mount Lebanon.

Jumblatt regularly published articles in Al Anbaa, which was founded by him in 1951.[13][14] His writings frequently contained criticisms against President Bechara El Khoury.[13] In 1952, he represented Lebanon at the Cultural Freedom Conference held in Switzerland. In August 1952, he organized a National Conference at Deir El Kamar, in the name of the National Socialist Front, calling for the resignation of the President. Due mainly to these pressures, the President resigned the same year.

The 1958 revolt

In 1952, after the resignation of Bechara El Khoury Jumblatt's bloc nominated Camille Chamoun for the presidency. Chamoun was elected president in September 1952.

In 1953, Jumblatt was re-elected Deputy for the fourth time. He founded the Popular Socialist Front in the same year and led the opposition against the new president, Camille Chamoun. During his presidency, the pro-Western President Chamoun tied Lebanon to the policies of the United States and the United Kingdom, who were at that time involved in the creation of the Baghdad Pact, comprising Hashemite Iraq, Turkey and Pakistan. This was seen by pan-Arabists as an imperialist coalition, and it was strongly opposed by the influential Nasserist movement. Jumblatt supported Egypt against an attack by Israel, France, and the United Kingdom in the Suez War of 1956, while Chamoun and parts of the Maronite Christian elite in Lebanon tacitly supported the invasion. The sectarian tensions of Lebanon greatly increased in this period, and both sides began to brace for violent conflict.

In 1957, Jumblatt failed for the first time in the parliamentary elections, complaining of electoral gerrymandering and election fraud by the authorities. A year later, he was the main leader of a major political uprising against Camille Chamoun's Maronite-dominated government, which soon escalated into street fights and guerilla attacks. While the revolt reflected a number of political and sectarian conflicts, it had a pan-Arabist ideology and was heavily supported through Syria by the newly formed United Arab Republic. The uprising ended after the United States intervened on the side of the Chamoun government and sent the U.S. Marine Corps to occupy Beirut. A political settlement followed by which Jumblatt's candidate Fuad Chehab was appointed new President of the Republic.

Uniting the opposition

Jumblatt chaired the Afro-Asian People's Conference in 1960 and founded the same year, the National Struggle Front (NSF) (جبهة النضال الوطني), a movement which gathered a large number of nationalist deputies. That same year, he was reelected Deputy for the fifth time and the NSF won 11 seats within the Lebanese Parliament. From 1960 to 1961 he was Minister for the second time, for the National Education portfolio and then in 1961, he was appointed Minister of Public Work and Planning. From 1961 to 1964 he served as Interior Minister.

On 8 May 1964, he won at the parliamentary elections for the sixth time. In 1965, he began joining Arab nationalist and progressivist politicians into a Nationalist Personalities Front. In 1966, he was appointed Minister of Public Work and Minister of PTT. He also represented Lebanon at the Congress of Afro-Asian Solidarity and presided over the parliamentary and popular delegation to the People’s Republic of China in 1966.

He supported the Palestinians in their struggle against Israel for ideological reasons, but also to garner support from the Palestinian fedayeen based in Lebanon's refugee camps. The presence in Lebanon of large numbers of Palestinian refugees was resented by most Christians, but Jumblatt strived to build a hard core of opposition around the Arab nationalist slogans of the Palestinian movement. Demanding a new Lebanese order based on secularism, socialism, Arabism and abolition of the sectarian system, Jumblatt began gathering disenchanted Sunnis, Shi'a and leftist Christians into an embryonic national opposition movement.

Build-up to civil war

On 9 May 1968, Jumblatt was reelected Deputy for the seventh time. In 1970, he was once again appointed Minister of the Interior, a reward for his last-minute switch of allegiance in the presidential election that year, which resulted in Suleiman Franjieh's victory by one vote over Elias Sarkis. His support of Franjieh, whose presidency 1970-1976 is regarded as egregiously corrupt, from a sometime supporter of the Chebab reforms, was crucial.[15] As Interior Minister, he legalized the Communist Party (LCP) and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). In 1972, Jumblatt was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union. The same year, he was reelected Deputy for the eighth time. The following year, he was unanimously elected Secretary General of the Arab Front, a movement supportive of the Palestinian revolution.

The 1970s in Lebanon were characterized by rapidly building tension between the Christian-dominated government and Muslim and leftist opposition forces, demanding better representation in the government apparatus and a stronger Lebanese commitment to the Arab world. The conflict took place more or less along the same sectarian and political lines as the 1958 rebellion.

Both the opposition and their mainly Christian opponents organized armed militias, and the risk of armed conflict increased steadily. Jumblatt had organized his own PSP into an armed force and made it the backbone of the Lebanese National Movement (LNM), a coalition of 12 left-wing parties and movements.[16] He also headed this coalition.[16] The LNM demanded the abolition of the sectarian quota system that permeated Lebanese politics, which discriminated against Muslims. The LNM was further joined by Palestinian radicals of the Rejectionist Front, and maintained good relations with the officially non-committal Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[17] The Palestinian presence in the ranks of the opposition was a new development compared to the 1958 conflict.

The Lebanese Civil War

In April 1975, a series of tit-for-tat killings culminating in a Phalangist massacre of Palestinian civilians, prompted full-blown fighting in Beirut. In August 1975, Jumblatt declared a program for reform of the Lebanese political system, and the LNM openly challenged the government's legitimacy. In October 1975, a new round of fighting broke out, and quickly spread throughout the country: the Lebanese Civil War had begun.

During the period between 1975 and 1976, Jumblatt acted as the main leader of the Lebanese opposition in the war, and with the aid of the PLO the LNM rapidly gained control over nearly 80% of Lebanon. They were on the verge of military decisiveness and putting the civil war to an end. Jumblatt paid a visit to Hafez al-Assad in March 1976, during which it was made clear that the Syrian position was very contrary to the one of the LNM.[18] This prompted an end of the political relationship between the two political leaders.[19] The Syrian intervened militarily on 1 June 1976, since the Syrian government claimed to fear a collapse of the Christian-dominated order and a subsequent Israeli invasion in order to aid the Christians and control the country, thus furthering Israel's influence in the region. However, this claim proved to be wrong for Israelis invaded Southern Lebanon in 1978 under the pretext of defending its northern borders from any possible Syrian aggression. Some 40,000 Syrian soldiers invaded Lebanon in 1976 and quickly smashed the LNM's favourable position; a truce was declared and the fighting subsided. During a pan-Arabic conference in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in the same year, an agreement was signed which included the presence of a Syrian military peacekeeping force under the auspices of the Arab League.[20]

Jumblatt's son Walid Jumblatt was kidnapped by Christian militants during the civil war and released after the intervention of former president Camille Chamoun.[21] Kamal Jumblatt was the target of an assassination attempt during the same period. Although he survived, his sister Linda was killed by a group of armed men who burst into their apartment in 1976.[21]

Personal life

Born in the Druze faith, Kamal Jumblatt adopted Christian teachings at his alma mater, the Lazarus Fathers Institute in Aintoura. He would regularly attend mass with his fellow students, and was found reciting Catholic prayers several years later over his cousin Hikmat Joumblatt's deathbed.[22]

Many of his acquaintances said that he understood the theology of Catholic teaching more than some priests

He was also very interested in Hinduism, in the early 1950s he visited India many times, where he met the Indian ambassador to Lebanon

On 1 May 1948, Jumblatt married May Arslan, daughter of Prince Shakib Arslan (the Arslans being the other prominent Lebanese Druze family), in Geneva.[23] Their only son, Walid Jumblatt, was born on 7 August 1949.

Kamal Jumblatt lectured extensively and wrote more than 1200 editorials in both Arabic and French. He is described as a socialist idealist under the influence of the European left movement.[24] He published his mémoires under the title I Speak for Lebanon.[23]

Death

On 16 March 1977, Kamal Jumblatt was gunned down in his car near the village of Baakline in the Chouf mountains by unidentified gunmen.[25][26][27] His bodyguard and driver also died in the attack.[25]

Prime suspects include the Ba'ath Party. In June 2005, former secretary general of the Lebanese Communist Party George Hawi claimed in an interview with Al Jazeera, that Rifaat al-Assad, brother of Hafez al Assad and uncle of Syria's President Bashar al-Assad, had been behind the killing of Jumblatt.[28]

His son Walid Jumblatt immediately succeeded him as the main Druze leader of Lebanon and as head of the PSP. He was elected leader of the PSP on 1 May 1977.[25] In 2015, Walid Jumblatt accused two Syrian officers, Ibrahim al-Hiwaija and Mohammed al-Khauli, as being responsible for killing his father.[29]

Kamal Jumblatt Centennial (1917-2017)

On the centennial anniversary of the birth of Kamal Jumblatt, the Leadership of the Progressive Socialist Party launched the " Kamal Jumblatt Centennial". During the celebration of this anniversary, a small bust of Kamal Jumblatt with a certificate signed by the PSP chief Walid Jumblatt with a yellow pin badge of the People's Liberation Army has been awarded to more than 22,000 PSP supporters, PLA supporters, National Movement supporters, and veterans, all over Lebanon.

See also

Notes

- ^ Some sources indicate that Kamal Jumblatt was born in Deir El Kamar.[4]

References

- ^ El-Khazen, Farid (2000). The Breakdown of the State in Lebanon, 1967-1976. Harvard University Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-674-08105-5. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Dar al Takadoumya".

- ^ "Timeline | Kamal Joumblatt Digital Library".

- ^ "Kamal Jumblatt". Wars of Lebanon. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Le camarade Kamal Bey Joumblatt, seigneur de Moukhtara (1/3)". www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Rowayheb, Marwan G. (18 February 2011). "Walid Jumblat and Political Alliances: The Politics of Adaptation". Middle East Critique. 20 (1): 47–66. doi:10.1080/19436149.2011.544535. ISSN 1943-6149.

- ^ Gambill, Gary C.; Nassif, Daniel (May 2001). "Walid Jumblatt". Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. 3 (5). Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b Schenk, Bernadette (1994). Kamal Gunbulat, Das arabisch-islamische Erbe und die Rolle der Drüsen in seiner Konzeption der libanesischen Geschichte. Berlin: Karl Schwarz Verlag. p. 60. ISBN 3-87997-225-7.

- ^ a b Schenk, Bernadette (1994) p.66–67

- ^ Schenk, Bernadette (1994) p.61

- ^ a b c "About Us". Ministry of Economy. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Schenk, Bernadette (1994) p.71

- ^ a b Jens Hanssen; Hicham Safieddine (Spring 2016). "Lebanon's al-Akhbar and Radical Press Culture: Toward an Intellectual History of the Contemporary Arab Left". The Arab Studies Journal. 24 (1): 201. JSTOR 44746852.

- ^ "Timeline. Al Anba'". Kamal Jumblatt Digital Library. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ David Gilmour, 'Lebanon, The Fractured Country', p.46

- ^ a b Yassin, Nasser (2010). "Violent urbanization and homogenization of space and place: Reconstructing the story of sectarian violence in Beirut" (PDF). World Institute for Development Economics Research. Working paper. 18. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Barry Barry Alexander Kosmin; Keysar, Ariela (1 May 2009). Secularism, Women and the State. ISSSC. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-692-00328-2. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Schenk, Bernadette (1994).p.87

- ^ Schenk, Bernadette (1994), p.88

- ^ Schenk, Bernadette (1994), p.89

- ^ a b "Leftist Jumblatt slain in Lebanon". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Beirut. UPI. 17 March 1977. Retrieved 15 December 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chammoun, Camille (1963). Crise au Moyen-Orient. Paris: Gallimard. p. 391.

- ^ a b Glass, Charles (1 March 2007). "The lord of no man's land: A guided tour through Lebanon's ceaseless war". Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Pokrupová, Michaela (2010). "The Chameleon's Jinking. The Druze Political Adaptation in Lebanon" (PDF). Beyond Globalisation: Exploring the Limits of Globalisation in the Regional Context (Conference Proceedings): 73–78.

- ^ a b c O'Ballance, Edgar (1998). Civil War in Lebanon, 1975-92. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-312-21593-4.

- ^ Llewellyn, Tim (2010). Spirit of the Phoenix: Beirut and the Story of Lebanon. I.B.Tauris. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-1-84511-735-1.

- ^ Knudsen, Are (2010). "Acquiescence to Assassinations in Post-Civil War Lebanon?". Mediterranean Politics. 15 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/13629391003644611. S2CID 154792218.

- ^ "George Hawi knew who killed Kamal Jumblatt". Ya Libnan. 22 June 2005. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "البيك في لحظة استقرار: الاغتيال ضد مصلحة سوريا". Al-Akhbar (in Arabic). 8 May 2015.

External links

- Podcast on Kamal Jumblatt's political life and legacy by The Lebanese Politics Podcast.

- Christopher Solomon, A look back at Kamal Jumblatt and the Progressive Socialist Party, 16 March 2019, Syria Comment