CORONA (satellite)

The CORONA[1] program was a series of American strategic reconnaissance satellites produced and operated by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Directorate of Science & Technology with substantial assistance from the U.S. Air Force. The CORONA satellites were used for photographic surveillance of the Soviet Union (USSR), China, and other areas beginning in June 1959 and ending in May 1972.

History

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite. Officially, Sputnik was launched to correspond with the International Geophysical Year, a solar period that the International Council of Scientific Unions declared would be ideal for the launching of artificial satellites to study Earth and the solar system. However, the launch led to public concern about the perceived technological gap between the West and the Soviet Union.[2] The unanticipated success of the mission precipitated the Sputnik Crisis, and prompted President Dwight D. Eisenhower to authorize the Corona program, a top priority reconnaissance program managed jointly by the Air Force and the CIA. Satellites were developed to photograph denied areas from space, provide information about Soviet missile capability and replace risky U-2 reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory.[3]

Overview

CORONA started under the name "Discoverer" as part of the WS-117L satellite reconnaissance and protection program of the U.S. Air Force in 1956. The WS-117L was based on recommendations and designs from the RAND Corporation.[4] The primary goal of the program was to develop a film-return photographic satellite to replace the U-2 spyplane in surveilling the Sino-Soviet Bloc, determining the disposition and speed of production of Soviet missiles and long-range bombers assets. The CORONA program was also used to produce maps and charts for the Department of Defense and other U.S. government mapping programs.[5]

The CORONA project was pushed forward rapidly following the shooting down of a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union on 1 May 1960.[6]

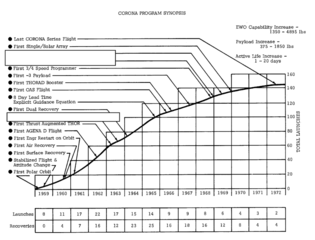

CORONA ultimately encompassed eight separate but overlapping series of satellites (dubbed "Keyhole" or KH[7]), launched from 1959 to 1972.[8]: 231 CORONA was complemented and ultimately succeeded by the higher resolution KH-7 Gambit and KH-8 Gambit 3 series of satellites.[9]

An alternative concurrent program to the CORONA program was SAMOS. That program included several types of satellite which used a different photographic method. This involved capturing an image on photographic film, developing the film aboard the satellite and then scanning the image electronically. The image was then transmitted via telemetry to ground stations. The Samos E-1 and Samos E-2 satellite programs used this system, but they were not able to take very many pictures and then relay them to the ground stations each day. Two later versions of the Samos program, such as the E-5 and the E-6, used the bucket-return approach pioneered with CORONA, but neither of the latter Samos series were successful.[10]

Spacecraft

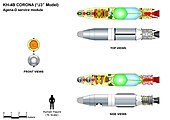

The CORONA satellites were designated KH-1, KH-2, KH-3, KH-4, KH-4A and KH-4B. KH stood for "Key Hole" or "Keyhole" (Code number 1010),[7] with the name being an analogy to the act of spying into a person's room by peering through their door's keyhole. The incrementing number indicated changes in the surveillance instrumentation, such as the change from single-panoramic to double-panoramic cameras. The "KH" naming system was first used in 1962 with KH-4, the earlier numbers being applied retroactively.[11]

- KH-1 CORONA main features

- KH-2 CORONA main features

- KH-3 CORONA main features

- KH-4 CORONA-M (Agena-B service module) main features

- KH-4 CORONA-M (Agena-D service module) main features

- KH-4A CORONA-J1 main features

- KH-4B CORONA-J3 main features

Below is a list of CORONA launches, as compiled by the United States Geological Survey.[12] This table lists government's designation of each type of satellite (C, C-prime, J-1, etc.), the resolution of the camera, and a description of the camera system.

| Time period | No. | Nickname | Resolution | Notes | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 1959 – August 1960 | Test | Engineering test flights | 5 systems; 1 recovery [13][14] | ||

| June 1959 – September 1960 | KH-1 | "CORONA", C | 7.5 m | First series of American imaging spy satellites. Each satellite carried a single panoramic camera and a single return vehicle. | 10 systems; 1 recovery |

| October 1960 – October 1961 | KH-2 | CORONA′, C′ (or "C-prime")* |

7.5 m | Improved single panoramic camera (affording differing orbits) [8]: 63–64 and a single return vehicle. | 10 systems; 6 recoveries |

| August 1961 – January 1962 | KH-3 | CORONA‴, C‴ (or "C-triple-prime")* |

7.5 m | Single panoramic camera and a single return vehicle. | 6 systems; 5 recoveries |

| February 1962 – December 1963 | KH-4 | CORONA-M, Mural | 7.5 m | Film return. Two panoramic cameras. | 26 systems; 20 recoveries |

| August 1963 – October 1969 | KH-4A | CORONA J-1 | 2.75 m | Film return with two reentry vehicles and two panoramic cameras. Large volume of imagery. | 52 systems; 94 recoveries |

| September 1967 – May 1972 | KH-4B | CORONA J-3 | 1.8 m | Film return with two reentry vehicles and two panoramic rotator cameras | 17 systems; 32 recoveries |

| February 1961 – August 1964 | KH-5 | ARGON | 140 m | Low-resolution mapping missions;single frame camera | 12 systems; 5 recoveries |

| March 1963 – July 1963 | KH-6 | LANYARD | 1.8 m | Experimental camera in a short-lived program | 3 systems; 1 recovery [8]: 231 |

*(The stray "quote marks" are part of the original designations of the first three generations of cameras.)

Program history

Discoverer

As American space launches were not classified until late 1961,[8]: 176 [15] the first CORONA satellites were cloaked with disinformation as being part of a space technology development program called Discoverer. To the public, Discoverer missions were scientific and engineering missions, the film-return capsules being used to return biological specimens. To facilitate this deception, several CORONA capsules were built to house a monkey passenger. Many test monkeys were lost during ground tests of the capsule's life support system.[8]: 50 The Discoverer cover proved to be cumbersome, inviting scrutiny from the scientific community. Discoverer 37, launched 13 January 1962, was the last CORONA mission to bear the Discoverer name. Subsequent CORONA missions were simply classified as "Department of Defense satellite launches".[16]: xiii–xiv

KH-1

The first series of CORONA satellites were the Keyhole 1 (KH-1) satellites based on the Agena-A upper stage, which offered housing and an engine that provided attitude control in orbit. The KH-1 payload included the C (for CORONA) single panoramic camera built by Fairchild Camera and Instrument with a f/5.0 aperture and 61 cm (24 in) focal length. It had a ground resolution of 12.9 m (42 ft). Film was returned from orbit by a single General Electric Satellite Return Vehicle (SRV). The SRV was equipped with a small onboard solid-fuel retro motor to deorbit the payload at the end of the mission. Recovery of the capsule was done in mid-air by a specially equipped aircraft.[17]

There were three camera-less test launches in the first half of 1959, none of them entirely successful. Discoverer 1 was a test vehicle carrying no SRV nor camera. Launched on 28 February 1959, it was the first man-made object put into a polar orbit, but only sporadically returned telemetry. Discoverer 2 (14 April 1959) carried a recovery capsule for the first time but no camera. The main bus performed well, but the capsule recovery failed, the SRV coming down over Spitzbergen rather than Hawaii. The capsule was never found. Discoverer 3 (3 June 1959), the first Discoverer to carry a biological package (four black mice in this case) failed to achieve orbit when its Agena crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

The pressure to orbit a photographic surveillance satellite to succeed the Lockheed U-2 was so great that operational, camera-equipped KH-1 launches began 25 June 1959 with the (unsuccessful) launching of Discoverer 4, despite there not having been a successful test of the life-support unit for biological passengers. This proved to be a moot point by this time as the link between the Discoverer series and living payloads had been established by the attempted flight of Discoverer 3.[8]: 51–54

The three subsequent Discoverers were successfully orbited, but all of their cameras failed when the film snapped during loading. Ground tests determined that the acetate-based film became brittle in the vacuum of space, something that had not been discovered even in high altitude, low pressure testing. The Eastman Kodak Company was tasked with creating a more resilient replacement. Kodak developed a technique of coating a high-resolution emulsion on a type of polyester from DuPont. Not only was the resulting polyester-based film resistant to vacuum brittling, it weighed half as much as the prior acetate-based film.[8]: 56

There were four more partially successful and unsuccessful missions in the KH-1 series before Discoverer 13 (10 August 1960), which managed a fully successful capsule recovery for the first time.[18] This was the first recovery of a man-made object from space, beating the Soviet Korabl Sputnik 2 by nine days. Discoverer 13 is now on display in the "Milestones of Flight" hall in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Two days after the 18 August 1960 launch of Discoverer 14, its film bucket was successfully retrieved in the Pacific Ocean by a Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar transport plane. This was the first successful return of a payload from orbit, occurring just one day before the launch of Korabl-Sputnik 2, a biosatellite that took into orbit the two Soviet space dogs, Belka and Strelka, and safely returned them to Earth.[19]

The impact of CORONA on American intelligence gathering was tremendous. With the success of Discoverer 14, which returned 16 lb (7.3 kg) of film and provided more coverage of the Soviet Union than all preceding U2 flights, for the first time the United States had a clear picture of the USSR's strategic nuclear capabilities. Before CORONA, the National Intelligence Estimates (NIE) of CIA were highly uncertain and strongly debated. Six months before Discoverer 14, an NIE predicted that the Soviets would have 140–200 ICBMs deployed by 1961. A month after the flight of Discoverer 14, that estimate was refined to just 10–25.[8]: 38–39

Additionally, CORONA increased the pace at which intelligence could be received, with satellites providing monthly coverage from the start. Photographs were more easily assessed by analysts and political leaders than covert agent reports, improving not just the amount of intelligence but its accessibility.[8]: 38–39

The KH-1 series ended with Discoverer 15 (13 September 1960), whose capsule successfully deorbited but sank into the Pacific Ocean and was not recovered.[20]

Later KH Series

In 1963, the KH-4 system was introduced with dual cameras and the program made completely secret by then president, John Kennedy. The Discoverer label was dropped and all launches became classified. Because of the increased satellite mass, the basic Thor-Agena vehicle’s capabilities were augmented by the addition of three Castor solid-fueled strap-on motors. On 28 February 1963, the first Thrust Augmented Thor lifted from Vandenberg Air Force Base at Launch Complex 75 carrying the first KH-4 satellite. The launch of the new and unproven booster went awry as one SRB failed to ignite. Eventually the dead weight of the strap-on motor dragged the Thor off its flight path, leading to a Range Safety destruct. It was suspected that a technician had not attached an umbilical on the SRB properly. Although some failures continued to occur during the next few years, the reliability rate of the program significantly improved with KH-4.[21][22] Maneuvering rockets were also added to the satellite beginning in 1963. These were different from the attitude stabilizing thrusters which had been incorporated from the beginning of the program. CORONA orbited in very low orbits to enhance resolution of its camera system. But at perigee (the lowest point in the orbit), CORONA endured drag from the atmosphere of Earth. In time, this could cause its orbit to decay and force the satellite to re-enter the atmosphere prematurely. The new maneuvering rockets were designed to boost CORONA into a higher orbit, and lengthen the mission time even if low perigees were used.[23] For use during unexpected crises, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) kept a CORONA in "R-7" status, meaning ready for launch in seven days. By the summer of 1965, NRO was able to maintain CORONA for launch within one day.[24]

Nine of the KH-4A and KH-4B missions included ELINT subsatellites, which were launched into a higher orbit.[25][26]

Some P-11 reconnaissance satellites were launched from KH-4A.[27]

At least two launches of Discoverer were used to test satellites for the Missile Defense Alarm System (MIDAS), an early missile-launch-detection program that used infrared cameras to detect the heat signature of launch vehicles launching to orbit.[28]

The last launch under the Discoverer cover name was Discoverer 38 on 26 February 1962. Its bucket was successfully recovered in midair during the 65th orbit (the 13th recovery of a bucket; the ninth one in midair).[29] Following this last use of the Discoverer name, the remaining launches of CORONA satellites were entirely TOP SECRET. The last CORONA launch was on 25 May 1972. The project ended when CORONA was replaced by the KH-9 Hexagon program.[30]

Technology

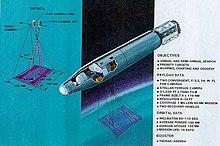

Cameras

The CORONA satellites used special 70 mm film with a 24 in (610 mm) focal length camera.[31] Manufactured by Eastman Kodak, the film was initially 0.0003 in (7.6 μm) thick, with a resolution of 170 lines per mm (0.04 inch) of film.[32][33] The contrast was 2-to-1.[32] (By comparison, the best aerial photography film produced in World War II could produce just 50 lines per mm (1250 per inch) of film).[32] The acetate-based film was later replaced with a polyester-based film stock that was more durable in Earth orbit.[34] The amount of film carried by the satellites varied over time. Initially, each satellite carried 8,000 ft (2,400 m) of film for each camera, for a total of 16,000 ft (4,900 m) of film.[32] But a reduction in the thickness of the film stock allowed more film to be carried.[34] In the fifth generation, the amount of film carried was doubled to 16,000 ft (4,900 m) of film for each camera for a total of 32,000 ft (9,800 m) of film. This was accomplished by a reduction in film thickness and with additional film capsules.[35] Most of the film shot was black and white. Infrared film was used on mission 1104, and color film on missions 1105 and 1008. Color film proved to have lower resolution, and so was never used again.[36]

The cameras were manufactured by the Itek Corporation.[37] A 12 in (30 cm), f/5 triplet lens was designed for the cameras.[38] Each lens was 7 in (18 cm) in diameter.[32] They were quite similar to the Tessar lenses developed in Germany by Carl Zeiss AG.[39] The cameras themselves were initially 5 ft (1.5 m) long, but later extended to 9 ft (2.7 m) in length.[40] Beginning with the KH-4 satellites, these lenses were replaced with Petzval f/3.5 lens.[36] The lenses were panoramic, and moved through a 70° arc perpendicular to the direction of the orbit.[32] A panoramic lens was chosen because it could obtain a wider image. Although the best resolution was only obtained in the center of the image, this could be overcome by having the camera sweep automatically ("reciprocate") back and forth across 70° of arc.[41] The lens on the camera was constantly rotating, to counteract the blurring effect of the satellite moving over the planet.[36]

The first CORONA satellites had a single camera, but a two-camera system was quickly implemented.[42] The front camera was tilted 15° aft, and the rear camera tilted 15° forward, so that a stereoscopic image could be obtained.[32] Later in the program, the satellite employed three cameras.[42] The third camera was employed to take "index" photographs of the objects being stereographically filmed.[43] The J-3 camera system, first deployed in 1967, placed the camera in a drum. This "rotator camera" (or drum) moved back and forth, eliminating the need to move the camera itself on a reciprocating mechanism.[44] The drum permitted the use of up to two filters and as many as four different exposure slits, greatly improving the variability of images that CORONA could take.[45] The first cameras could resolve images on the ground down to 40 ft (12 m) in diameter. Improvements in the imaging system were rapid, and the KH-3 missions could see objects 10 ft (3.0 m) in diameter. Later missions would be able to resolve objects just 5 ft (1.5 m) in diameter.[46] 3 ft (0.91 m) resolution was found to be the optimum resolution for quality of image and field of view.[citation needed]

The initial CORONA missions suffered from mysterious border fogging and bright streaks which appeared irregularly on the returned film. Eventually, a team of scientists and engineers from the project and from academia (among them Luis Alvarez, Sidney Beldner, Malvin Ruderman, Arthur Glines,[47] and Sidney Drell) determined that electrostatic discharges (called corona discharges) caused by some of the components of the cameras were exposing the film.[48][49] Corrective measures included better grounding of the components, improved film rollers that did not generate static electricity, improved temperature controls, and a cleaner internal environment.[49] Although improvements were made to reduce the corona, the final solution was to load the film canisters with a full load of film and then feed the unexposed film through the camera onto the take-up reel with no exposure. This unexposed film was then processed and inspected for corona. If none was found or the corona observed was within acceptable levels, the canisters were certified for use and loaded with fresh film for a launch mission.

Calibration

CORONA satellites were allegedly calibrated using the calibration targets located outside of Casa Grande, Arizona. The targets consisted of concrete arrows located in and to the south of the city, and may have helped to calibrate the cameras of the satellites.[50][51][52] These claims about the purpose of the targets, perpetuated by online forums and featured in National Geographic and NPR articles, have since been disputed, with aerial photogrammetry proposed as a more likely purpose for them.[53]

Recovery

Film was retrieved from orbit via a reentry capsule (nicknamed "film bucket"), designed by General Electric, which separated from the satellite and fell to Earth.[54] After the fierce heat of reentry was over, the heat shield surrounding the vehicle was jettisoned at 60,000 ft (18 km) and parachutes deployed.[55] The capsule was intended to be caught in mid-air by a passing airplane[56] towing an airborne claw which would then winch it aboard, or it could land at sea.[57] A salt plug in the base would dissolve after two days, allowing the capsule to sink if it was not picked up by the United States Navy.[58] After Reuters reported on a reentry vehicle's accidental landing and discovery by Venezuelan farmers in mid-1964, capsules were no longer labeled "SECRET" but offered a reward in eight languages for aerial footage return to the United States.[59] Beginning with flight number 69, a two-capsule system was employed.[48] This also allowed the satellite to go into passive (or "zombie") mode, shutting down for as many as 21 days before taking images again.[35] Beginning in 1963, another improvement was "Lifeboat", a battery-powered system that allowed for ejection and recovery of the capsule in case power failed.[21][60] The film was processed at Eastman Kodak's Hawkeye facility in Rochester, New York.[61]

The CORONA film bucket was later adapted for the KH-7 GAMBIT satellites, which took higher resolution photos.

Launch

CORONA were launched by a Thor-Agena rocket, which used a Thor first stage and an Agena as the second stage of the rocket lifting the CORONA into orbit.

The first satellites in the program orbited at altitudes 100 mi (160 km) above the surface of the Earth, although later missions orbited even lower at 75 mi (121 km).[36] Originally, CORONA satellites were designed to spin along their main axis so that the satellite would remain stable. Cameras would take photographs only when pointed at the Earth. The Itek camera company, however, proposed to stabilize the satellite along all three axes—keeping the cameras permanently pointed at the earth.[39] Beginning with the KH-3 version of the satellite, a horizon camera took images of several key stars.[43] A sensor used the satellite's side thruster rockets to align the rocket with these "index stars", so that it was correctly aligned with the Earth and the cameras pointed in the right direction.[62] Beginning in 1967, two horizon cameras were used. This system was known as the Dual Improved Stellar Index Camera (DISIC).[45]

Operations

The United States Air Force credits the Sunnyvale Air Force Station (now Onizuka Air Force Station) as being the "birthplace of the CORONA program".[63] In May 1958, the Department of Defense directed the transfer of the WS-117L program to Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). In FY1958, WS-117L was funded by the USAF at a level of US$108.2 million (inflation adjusted US$1.14 billion in 2025). For DISCOVERER, the Air Force and ARPA spent a combined sum of US$132.3 million in FY1959 (inflation adjusted US$1.38 billion in 2025) and US$101.2 million in FY1960 (inflation adjusted US$1.04 billion in 2025).[64] According to John N. McMahon, the total cost of the CORONA program amounted to $US850 million.[65]

The procurement and maintenance of the CORONA satellites were managed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which used cover arrangements lasting from April 1958 to 1969 to get access to the Palo Alto plant of the Hiller Helicopter Corporation for the production.[66] At this facility, the rocket's second stage Agena, the cameras, film cassettes, and re-entry capsule were assembled and tested before shipment to Vandenberg Air Force Base.[67] In 1969, assembly duties were relocated to the Lockheed facilities in Sunnyvale, California.[68] (The NRO was worried that, as CORONA was phased out, skilled technicians worried about their jobs would quit the program—leaving CORONA without staff. The move to Sunnyvale ensured that enough skilled staff would be available.)

The decisions regarding what to photograph were made by the CORONA Target Program. CORONA satellites were placed into near-polar orbits.[46] This software, run by an on-board computer, was programmed to operate the cameras based on the intelligence targets to be imaged, the weather, the satellite's operational status, and what images the cameras had already captured.[69] Ground control for CORONA satellites was initially conducted from Stanford Industrial Park, an industrial park on Page Mill Road in Palo Alto, California. It was later moved to Sunnyvale Air Force Base near Sunnyvale, California.[70]

Design staff

Minoru S. "Sam" Araki, Francis J. Madden, Edward A. Miller, James W. Plummer, and Don H. Schoessler were responsible for the design, development, and operation of CORONA. For their role in creating the first space-based Earth photographic observation systems, they were awarded the Charles Stark Draper Prize in 2005.[71] Walter Gize, of Palo Alto, was the program design senior electrical engineer for 'power' requirements.

Declassification

The CORONA program was officially classified top secret until 1992. On 22 February 1995, the photos taken by the CORONA satellites, and also by two contemporary programs (ARGON and KH-6 LANYARD) were declassified under an Executive Order signed by President Bill Clinton.[72] The further review by photo experts of the "obsolete broad-area film-return systems other than CORONA" mandated by President Clinton's order led to the declassification in 2002 of the photos from the KH-7 and the KH-9 low-resolution cameras.[73]

The declassified imagery has since been used by a team of scientists from the Australian National University to locate and explore ancient habitation sites, pottery factories, megalithic tombs, and Palaeolithic archaeological remains in northern Syria.[74][75] Similarly, scientists at Harvard have used the imagery to identify prehistoric traveling routes in Mesopotamia.[76][77]

The U.S. Geological Survey hosts more than 860,000 images of the Earth’s surface from between 1960 and 1972 from CORONA, ARGON, and LANYARD programs.

Launches

| Mission No. | Cover Name | Launch Date | NSSDC ID No. | Alt. Name | Camera | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R&D | Discoverer Zero [78] | 21 January 1959 | 1959-F01 | none | Agena ullage/separation rockets ignited on the pad while the launch vehicle was being fueled prior to the flight. | |

| R&D | Discoverer 1 | 28 Feb 1959 | 1959-002A | 1959 Beta 1 | none | Decay: 17 March 1959.[5] |

| R&D | Discoverer 2 | 13 April 1959 | 1959-003A | 1959 GAM | none | First three-axis stabilized satellite; capsule recovery failed. |

| R&D | Discoverer 3 | 3 June 1959 | DISCOV3 | 1959-F02 | none | Agena guidance failure. Vehicle fell into the Pacific Ocean |

| 9001 | Discoverer 4 | 25 June 1959 | DISC4 | 1959-U01 | KH-1 | Insufficient Agena engine thrust. Vehicle fell into the Pacific Ocean |

| 9002 | Discoverer 5 | 13 Aug 1959 | 1959-005A | 1959 EPS 1 | KH-1 | Mission failed. Power supply failure. No recovery. |

| 9003 | Discoverer 6 | 19 Aug 1959 | 1959-006A | 1959 ZET | KH-1 | Mission failed. Retro rockets malfunctioned negating recovery. |

| 9004 | Discoverer 7 | 7 Nov 1959 | 1959-010A | 1959 KAP | KH-1 | Mission failed. Satellite tumbled in orbit. |

| 9005 | Discoverer 8 | 20 Nov 1959 | 1959-011A | 1959 LAM | KH-1 | Mission failed. Eccentric orbit negating recovery. |

| 9006 | Discoverer 9 | 4 February 1960 | DiSC9 | 1960-F01 | KH-1 | Agena accidentally damaged during on-pad servicing. Premature cutoff and staging signal sent to Thor. |

| 9007 | Discoverer 10 | 19 Feb 1960 | DISC10 | 1960-F02 | KH-1 | Control failure, RSO destruct T+52 sec after launch |

| 9008 | Discoverer 11 | 15 April 1960 | 1960-004A | 1960 DEL | KH-1 | Attitude control system malfunctioned. No film capsule recovery. |

| R&D | Discoverer 12 | 29 June 1960 | DISC12 | 1960-F08 | none | Agena attitude control malfunction. No orbit. |

| R&D | Discoverer 13 | 10 Aug 1960 | 1960-008A | 1960 THE | none | Tested capsule recovery system; first successful capture. |

| 9009 | Discoverer 14 | 18 Aug 1960 | 1960-010A | 1960 KAP | KH-1 | First successful recovery of IMINT from space. Cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 9010 | Discoverer 15 | 13 September 1960 | 1960-012A | 1960 MU | KH-1 | Mission failed. Attained orbit successfully. Capsule sank prior to retrieval. |

| 9011 | Discoverer 16 | 26 Oct 1960 | 1960-F15 | 1960-F15 | KH-2 | Agena failed to separate from Thor. |

| 9012 | Discoverer 17 | 12 November 1960 | 1960-015A | 1960 OMI | KH-2 | Mission failed. Obtained orbit successfully. Film separated before any camera operation leaving only 1.7 ft (0.52 m) of film in capsule. |

| 9013 | Discoverer 18 | 7 Dec 1960 | 1960-018A | 1960 SIG | KH-2 | First successful mission employing KH-2 camera system. |

| RM-1 | Discoverer 19 | 20 Dec 1960 | 1960-019A | 1960 TAU | none | Test of Missile Defense Alarm System |

| 9014A | Discoverer 20 | 17 Feb 1961 | 1961-005A | 1961 EPS 1 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| RM-2 | Discoverer 21 | 18 Feb 1961 | 1961-006A | 1961 ZET | none | Test of restartable rocket engine |

| 9015 | Discoverer 22 | 30 Mar 1961 | DISC22 | 1961-F02 | KH-2 | Agena control malfunction. No orbit. |

| 9016A | Discoverer 23 | 8 April 1961 | 1961-011A | 1961 LAM 1 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9018A | Discoverer 24 | 8 June 1961 | DISC24 | 1961-F05 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9017 | Discoverer 25 | 16 June 1961 | 1961-014A | 1961 XI 1 | KH-2 | Capsule recovered from water on orbit 32. Streaks throughout film. |

| 9019 | Discoverer 26 | 7 July 1961 | 1961-016A | 1961 PI | KH-2 | Main camera malfunctioned on pass 22. |

| 9020A | Discoverer 27 | 21 July 1961 | DISC27 | 1961-F07 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9021 | Discoverer 28 | 4 Aug 1961 | DISC28 | 1961-F08 | KH-2 | Thor guidance failure. RSO destruct at T+60 seconds. |

| 9022 | Discoverer 30 | 12 Sep 1961 | 1961-024A | 1961 OME 1 | KH-3 | Best mission to date. Same out-of-focus condition as in 9023. |

| 9023 | Discoverer 29 | 30 Aug 1961 | 1961-023A | 1961 PSI | KH-3 | First use of KH-3 camera system. All frames out of focus. |

| 9024 | Discoverer 31 | 17 September 1961 | 1961-026A | 1961 A BET | KH-3 | Mission failed. Power failure and loss of control gas on orbit 33. Capsule was not recovered. |

| 9025 | Discoverer 32 | 13 Oct 1961 | 1961-027A | 1961 A GAM 1 | KH-3 | Capsule recovered on orbit 18. 96% of film out of focus. |

| 9026 | Discoverer 33 | 23 Oct 1961 | DISC33 | 1961-F10 | KH-3 | Satellite failed to separate from Thor booster, no orbit. |

| 9027 | Discoverer 34 | 5 Nov 1961 | 1961-029A | 1961 A EPS 1 | KH-3 | Mission failed. Improper launch angle resulted in extreme orbit. Gas valve failed |

| 9028 | Discoverer 35 | 15 Nov 1961 | 1961-030A | 1961 A ZET 1 | KH-3 | All cameras operated satisfactorily. Grainy emulsion noted. |

| 9029 | Discoverer 36 | 12 Dec 1961 | 1961-034A | 1961 A KAP 1 | KH-3 | Best mission to date. Launch carried OSCAR 1 to orbit. |

| 9030 | Discoverer 37 | 13 Jan 1962 | DISC37 | 1962-F01 | KH-3 | Mission failed. No orbit. |

| 9031 | Discoverer 38 | 27 Feb 1962 | 1962-005A | 1962 EPS 1 | KH-4 | First mission of the KH-4 series. Much of film slightly out of focus. |

| 9032 | 1962 Lambda 1 | 18 April 1962 | 1962-011A | 1962 LAM 1 | KH-4 | Best mission to date. |

| 9033 | FTV 1125 | 28 April 1962 | 1962-017A | 1962 RHO 1 | KH-4 | Mission failed. Parachute ejector squibs holding parachute container cover failed to fire. No recovery. |

| 9034A | FTV 1126 | 15 May 1962 | 1962-018A | 1962 SIG 1 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9035 | FTV 1128 | 30 May 1962 | 1962-021A | 1962 PHI 1 | KH-4 | Slight corona static on film. |

| 9036 | FTV 1127 | 2 June 1962 | 1962-022A | 1962 CHI 1 | KH-4 | Mission failed. During air catch. Launch carried OSCAR 2 to orbit. |

| 9037 | FTV 1129 | 23 June 1962 | 1962-026A | 1962 A BET | KH-4 | Corona static occurs on some film. |

| 9038 | FTV 1151 | 28 June 1962 | 1962-027A | 1962 A GAM | KH-4 | Severe corona static. |

| 9039 | FTV 1130 | 21 July 1962 | 1962-031A | 1962 A ETA | KH-4 | Aborted after 6 photo passes. Heavy corona and radiation fog. |

| 9040 | FTV 1131 | 28 July 1962 | 1962-032A | 1962 A THE | KH-4 | No filters on slave horizon cameras. Heavy corona and radiation fog. |

| 9041 | FTV 1152 | 2 Aug 1962 | 1962-034A | 1962 A KAP 1 | KH-4 | Severe corona and radiation fog. |

| 9042A | FTV 1132 | 1 Sep 1962 | 1962-044A | 1962 A UPS | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9043 | FTV 1133 | 17 September 1962 | 1962-046A | 1962 A CHI | KH-4 | placed in highly eccentric orbit (207 x 670 km), capsule called down after one day, film suffered severe radiation fog due to South Atlantic Anomaly crossing[79][80][81] |

| 9044 | FTV 1153 | 29 Aug 1962 | 1962-042A | 1962 A SIG | KH-4 | Erratic vehicle attitude. Radiation fog minimal. |

| 9045 | FTV 1154 | 29 Sep 1962 | 1962-050A | 1962 B BET | KH-4 | First use of stellar camera |

| 9046A | FTV 1134 | 9 Oct 1962 | 1962-053A | 1962 B EPS | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9047 | FTV 1136 | 5 Nov 1962 | 1962-063A | 1962 B OMI | KH-4 | Camera door malfunctioned |

| 9048 | FTV 1135 | 24 Nov 1962 | 1962-065A | 1962 B RHO | KH-4 | Some film exposed through base. |

| 9049 | FTV 1155 | 4 Dec 1962 | 1962-066A | 1962 B SIG | KH-4 | Mission failed. During air catch chute tore |

| 9050 | FTV 1156 | 14 Dec 1962 | 1962-069A | 1962 B PHI | KH-4 | Best mission to date. |

| 9051 | OPS 0048 | 7 Jan 1963 | 1963-002A | 1963-002A | KH-4 | Erratic vehicle attitude. Frame ephemeris not created. |

| 9052 | OPS 0583 | 28 Feb 1963 | 1963-F02 | 1963-F02 | KH-4 | Mission failed. Destroyed by range safety officer |

| 9053 | OPS 0720 | 1 Apr 1963 | 1963-007A | 1963-007A | KH-4 | Best imagery to date. |

| 9054 | OPS 0954 | 12 Jun 1963 | 1963-019A | 1963-019A | KH-4 | Some imagery seriously affected by corona. |

| 9055A | OPS 1008 | 26 Apr 1963 | 1963-F07 | 1963-F07 | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9056 | OPS 0999 | 26 Jun 1963 | 1963-025A | 1963-025A | KH-4 | Experimental camera carried. Film affected by light leaks. |

| 9057 | OPS 1266 | 19 Jul 1963 | 1963-029A | 1963-029A | KH-4 | Best mission to date. |

| 9058A | OPS 1561 | 29 Aug 1963 | 1963-035A | 1963-035A | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9059A | OPS 2437 | 29 Oct 1963 | 1963-042A | 1963-042A | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9060 | OPS 2268 | 9 Nov 1963 | 1963-F14 | 1963-F14 | KH-4 | Mission failed. No orbit. |

| 9061 | OPS 2260 | 27 Nov 1963 | 1963-048A | 1963-048A | KH-4 | Mission failed. Return capsule separated from satellite but remained in orbit. |

| 9062 | OPS 1388 | 21 Dec 1963 | 1963-055A | 1963-055A | KH-4 | Corona static fogged much of film. |

| 9065A | OPS 2739 | 21 Aug 1964 | 1964-048A | 1964-048A | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 9066A | OPS 3236 | 13 Jun 1964 | 1964-030A | 1964-030A | KH-5 | See KH-5 |

| 1001 | OPS 1419 | 24 Aug 1963 | 1963-034A | 1963-034A | KH-4A | First mission of KH-4A. Some film was fogged. Two buckets but 1001-2 was never recovered. |

| 1002 | OPS 1353 | 23 Sep 1963 | 1963-037A | 1963-037A | KH-4A | Severe light leaks |

| 1003 | OPS 3467 | 24 Mar 1964 | 1964-F04 | 1964-F04 | KH-4A | Mission failed. Guidance system failed. No orbit. |

| 1004 | OPS 3444 | 15 Feb 1964 | 1964-008A | 1964-008A | KH-4A | Main cameras operated satisfactorily. Minor degradations due to static and light leaks. |

| 1005 | OPS 2921 | 27 Apr 1964 | 1964-022A | 1964-022A | KH-4A | Mission failed. Recovery vehicle impacted in Venezuela. |

| 1006 | OPS 3483 | 4 June 1964 | 1964-027A | 1964-027A | KH-4A | Highest quality imagery attained to date from the KH-4 system. |

| 1007 | OPS 3754 | 19 Jun 1964 | 1964-032A | 1964-032A | KH-4A | Out-of-focus area on some film. |

| 1008 | OPS 3491 | 10 Jun 1964 | 1964-037A | 1964-037A | KH-4A | Cameras operated satisfactorily |

| 1009 | OPS 3042 | 5 Aug 1964 | 1964-043A | 1964-043A | KH-4A | Cameras operated successfully. |

| 1010 | OPS 3497 | 14 Sep 1964 | 1964-056A | 1964-056A | KH-4A | Small out of focus areas on both cameras at random times throughout the mission. |

| 1011 | OPS 3333 | 5 Oct 1964 | 1964-061A | 1964-061A | KH-4A | Primary mode of recovery failed on second portion of the mission (1011-2). Small out of focus areas present at random on both cameras. |

| 1012 | OPS 3559 | 17 Oct 1964 | 1964-067A | 1964-067A | KH-4A | Vehicle attitude became erratic on the second portion of the mission necessitating an early recovery. |

| 1013 | OPS 5434 | 2 Nov 1964 | 1964-071A | 1964-071A | KH-4A | Program anomaly occurred immediately after launch when both cameras operated for 417 frames. Main cameras ceased operation on rev 52D of first portion of mission negating second portion. About 65% of aft camera film is out of focus. |

| 1014 | OPS 3360 | 18 Nov 1964 | 1964-075A | 1964-075A | KH-4A | Cameras operated successfully. |

| 1015 | OPS 3358 | 19 Dec 1964 | 1964-085A | 1964-085A | KH-4A | Discrepancies in planned and actual coverage due to telemetry problems during the first 6 revolutions. Small out-of-focus areas on film from aft camera. |

| 1016 | OPS 3928 | 15 Jan 1965 | 1965-002A | 1965-002A | KH-4A | Smearing of highly reflective images due to reflections within camera. |

| 1017 | OPS 4782 | 25 Feb 1965 | 1965-013A | 1965-013A | KH-4A | Capping shutter malfunction occurred during last 5 passes of mission. |

| 1018 | OPS 4803 | 25 Mar 1965 | 1965-026A | 1965-026A | KH-4A | Cameras operated successfully. First KH-4A reconnaissance system to be launched into a retrograde orbit. |

| 1019 | OPS 5023 | 29 Apr 1965 | 1965-033A | 1965-033A | KH-4A | Cameras operated successfully. Malfunction in recovery mode on 1019-2 negated recovery. |

| 1020 | OPS 8425 | 9 Jun 1965 | 1965-045A | 1965-045A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. Erratic attitude caused an early recovery after the second day of 1020–2. |

| 1021 | OPS 8431 | 18 May 1965 | 1965-037A | 1965-037A | KH-4A | Aft camera ceased operation on pass 102. |

| 1022 | OPS 5543 | 19 Jun 1965 | 1965-057A | 1965-057A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1023 | OPS 7208 | 17 Aug 1965 | 1965-067A | 1965-067A | KH-4A | Program anomaly caused the fore camera to cease operation during revolutions 103–132. |

| 1024 | OPS 7221 | 22 Sep 1965 | 1965-074A | 1965-074A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. Cameras not operated on passes 88D-93D. |

| 1025 | OPS 5325 | 5 Oct 1965 | 1965-079A | 1965-079A | KH-4A | Main cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1026 | OPS 2155 | 28 Oct 1965 | 1965-086A | 1965-086A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1027 | OPS 7249 | 9 Dec 1965 | 1965-102A | 1965-102A | KH-4A | Erratic attitude necessitated recovery after two days of operation. All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1028 | OPS 4639 | 24 Dec 1965 | 1965-110A | 1965-110A | KH-4A | Cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1029 | OPS 7291 | 2 Feb 1966 | 1966-007A | 1966-007A | KH-4A | Both panoramic cameras were operational throughout. |

| 1030 | OPS 3488 | 9 Mar 1966 | 1966-018A | 1966-018A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1031 | OPS 1612 | 7 April 1966 | 1966-029A | 1966-029A | KH-4A | The aft-looking camera malfunctioned after the recovery of bucket 1. No material was received in bucket 2 (1031-2). |

| 1032 | OPS 1508 | 3 May 1966 | 1966-F05A | 1966-F05 | KH-4A | Mission failed. Vehicle failed to achieve orbit. |

| 1033 | OPS 1778 | 24 May 1966 | 1966-042A | 1966-042A | KH-4A | The stellar camera shutter of bucket 2 remained open for approximately 200 frames. |

| 1034 | OPS 1599 | 21 June 1966 | 1966-055A | 1966-055A | KH-4A | Failure of velocity altitude programmer produced poor imagery after revolution 5. |

| 1035 | OPS 1703 | 20 September 1966 | 1966-085A | 1966-085A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. First mission flown with pan geometry modification. |

| 1036 | OPS 1545 | 9 Aug 1966 | 1966-072A | 1966-072A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1037 | OPS 1866 | 8 Nov 1966 | 1966-102A | 1966-102A | KH-4A | Second pan geometry mission. Higher than normal base plus fog encountered on both main camera records. |

| 1038 | OPS 1664 | 14 Jan 1967 | 1967-002A | 1967-002A | KH-4A | Fair image quality. |

| 1039 | OPS 4750 | 22 Feb 1967 | 1967-015A | 1967-015A | KH-4A | Normal KH-4 mission. Light from horizon camera on both main camera records during 1039–1. |

| 1040 | OPS 4779 | 30 Mar 1967 | 1967-029A | 1967-029A | KH-4A | Satellite flown nose first. |

| 1041 | OPS 4696 | 9 May 1967 | 1967-043A | 1967-043A | KH-4A | Due to the failure of the booster cut-off switch, the satellite went into a highly eccentric orbit. There was significant image degradation. |

| 1042 | OPS 3559 | 16 June 1967 | 1967-062A | 1967-062A | KH-4A | Small out-of-focus area in forward camera of 1042–1. |

| 1043 | OPS 4827 | 7 Aug 1967 | 1967-076A | 1967-076A | KH-4A | Forward camera film came out of the rails on pass 230D. Film degraded past this point. |

| 1044 | OPS 0562 | 2 Nov 1967 | 1967-109A | 1967-109A | KH-4A | All cameras operated fine. |

| 1045 | OPS 2243 | 24 Jan 1968 | 1968-008A | 1968-008A | KH-4A | All cameras operated satisfactorily. |

| 1046 | OPS 4849 | 14 Mar 1968 | 1968-020A | 1968-020A | KH-4A | Image quality good for 1046-1 and fair for 1046–2. |

| 1047 | OPS 5343 | 20 June 1968 | 1968-052A | 1968-052A | KH-4A | Out-of-focus imagery is present on both main camera records. |

| 1048 | OPS 0165 | 18 Sep 1968 | 1968-078A | 1968-078A | KH-4A | Film in the forward camera separated and camera failed on mission 1048-2 |

| 1049 | OPS 4740 | 12 Dec 1968 | 1968-112A | 1968-112A | KH-4A | Degraded film |

| 1050 | OPS 3722 | 19 Mar 1969 | 1969-026A | 1969-026A | KH-4A | Due to abnormal rotational rates after revolution 22 |

| 1051 | OPS 1101 | 2 May 1969 | 1969-041A | 1969-041A | KH-4A | Imagery of both pan camera records is soft and lacks crispness and edge sharpness. |

| 1052 | OPS 3531 | 22 Sep 1969 | 1969-079A | 1969-079A | KH-4A | Last of the KH-4A missions |

| 1101 | OPS 5089 | 15 Sep 1967 | 1967-087A | 1967-087A | KH-4B | First mission of the KH-4B series. Best film to date. |

| 1102 | OPS 1001 | 09 Dec 1967 | 1967-122A | 1967-122A | KH-4B | Noticeable image smear for forward camera |

| 1103 | OPS 1419 | 1 May 1968 | 1968-039A | 1968-039B | KH-4B | Out-of-focus imagery is present on both main camera records. |

| 1104 | OPS 5955 | 7 August 1968 | 1968-065A | 1968-065A | KH-4B | Best imagery to date on any KH-4. Bicolor and color infrared experiments conducted, incl. SO-180 IR camouflage detection film[82] |

| 1105 | OPS 1315 | 3 Nov 1968 | 1968-098A | 1968-098A | KH-4B | Image quality is variable and displays areas of soft focus and image smear. |

| 1106 | OPS 3890 | 5 Feb 1969 | 1969-010A | 1969-010A | KH-4B | The best image quality to date. |

| 1107 | OPS 3654 | 24 July 1969 | 1969-063A | 1969-063A | KH-4B | Forward camera failed on pass 1 and remained inoperative throughout the rest of the mission. |

| 1108 | OPS 6617 | 4 December 1969 | 1969-105A | 1969-105A | KH-4B | Cameras operated satisfactorily and the mission carried 811 ft (247 m) of aerial color film added to the end of the film supply. |

| 1109 | OPS 0440 | 4 March 1970 | 1970-016A | 1970-016A | KH-4B | Cameras operated satisfactorily but the overall image quality of both the forward and aft records is variable. |

| 1110 | OPS 4720 | 20 May 1970 | 1970-040A | 1970-040A | KH-4B | The overall image quality is less than that provided by recent missions and 2 |

| 1111 | OPS 4324 | 23 June 1970 | 1970-054A | 1970-054A | KH-4B | The overall image quality is good. |

| 1112 | OPS 4992 | 18 Nov 1970 | 1970-098A | 1970-098A | KH-4B | The forward camera failed on pass 104 and remained inoperative throughout the rest of the mission. |

| 1113 | OPS 3297 | 17 Feb 1971 | 1971-F01A | 1971-F01 | KH-4B | Failure of Thor booster, destroyed shortly after launch |

| 1114 | OPS 5300 | 24 March 1971 | 1971-022A | 1971-022A | KH-4B | Overall image quality good, comparable to the best of past missions. On-board program failed after pass 235 |

| 1115 | OPS 5454 | 10 Sep 1971 | 1971-076A | 1971-076A | KH-4B | Overall image quality good |

| 1116 | OPS 5640 | 19 April 1972 | 1972-032A | 1972-032A | KH-4B | Very successful mission and image quality was good. |

| 1117 | OPS 6371 | 25 May 1972 | 1972-039A | 1972-039A | KH-4B | Last KH-4B. Very successful, failure to deploy one solar panel and leak in Agena gas system shortened mission from 19 to 6 days[81] |

Image gallery

- Air Force Satellite Control Facility during recovery operations

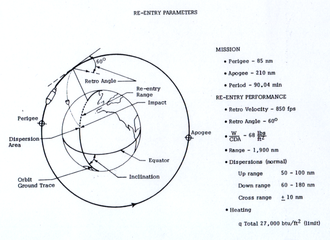

- CORONA re-entry parameters

- "A Point in Time: The CORONA Story" – a documentary movie about the first in history project of spy satellites, created by the CIA and NRO in 1995 to commemorate declassification of CORONA project

- CORONA full-frame stereo pair image of the Salton Sea California

- Stereo medium CORONA image of Dinuba, California 1970

In popular culture

The 1963 thriller novel Ice Station Zebra and its 1968 film adaptation were inspired, in part, by news accounts from 17 April 1959, about a missing experimental CORONA satellite capsule (Discoverer 2) that inadvertently landed near Spitzbergen on 13 April 1959. While Soviet agents may have recovered the vehicle,[67][83] it is more likely that the capsule landed in water and sank.[59]

See also

- Cold War

- Deep Black (1986 book)

- KH-5 ARGON, KH-6 LANYARD, KH-7 GAMBIT, KH-8 GAMBIT 3

- KH-9 Hexagon "Big Bird"

- KH-10 DORIAN or Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL program)

- KH-11, KH-12, KH-13.

- Richard M. Bissell Jr.

- SAMOS

- Satellite imagery

- Zenit

References

- ^ CIA History Staff (1995). CORONA America's First Satellite Program (PDF). CIA Codl War Records. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "Sputnik Launched". Archived from the original on 7 March 2010.

- ^ Angelo, Joseph A. (14 May 2014). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. Infobase. p. 489. ISBN 9781438110189.

- ^ Rich, Michael D. (1998). "RAND's Role in the CORONA Program". RAND Corporation. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 1". NSSDCA. NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 1". NSSDCA. NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: United States; Central Intelligence Agency; Ruffner, Kevin Conley (1995). CORONA America's first satellite program. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency. p. xiii. OCLC 42006243.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: United States; Central Intelligence Agency; Ruffner, Kevin Conley (1995). CORONA America's first satellite program. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency. p. xiii. OCLC 42006243.

- ^ a b Yenne, Bill (1985). The Encyclopedia of US Spacecraft. Exeter Books (A Bison Book), New York. ISBN 978-0-671-07580-4. p. 82 Key Hole

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Day, Dwayne A.; Logsdon, John M.; Latell, Brian (1998). Eye in the Sky: The Story of the Corona Spy Satellites. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-830-4. OCLC 36783934.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "HEXAGON America's eyes in space" (PDF). Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "HEXAGON America's eyes in space" (PDF). Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan (26 August 2000). "9.3.1: SAMOS". Jonathon's Space Report. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Corona Program". Mission and Spacecraft Library - NASA. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

This designation system came into use during 1962 with the 4th camera system, with its predecessors retroactively identified as KH-1, KH-2, and KH-3.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Declassified Intelligence Satellite Photographs Fact Sheet 090-96". United States Geological Survey. February 1998. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Declassified Intelligence Satellite Photographs Fact Sheet 090-96". United States Geological Survey. February 1998. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007.

- ^ "Discoverer 2, 3, 12, 13". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Discoverer 1". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Space Science and Exploration". Collier's Encyclopedia. Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. 1964. OCLC 1032873498.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Robert Perry (October 1973). A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume 1 (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. OCLC 794229594.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Robert Perry (October 1973). A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume 1 (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. OCLC 794229594.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter. "KH-1 Corona". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 13 – 1960-008A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 13 – 1960-008A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Sputnik 5 – 1960-011A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Sputnik 5 – 1960-011A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 15 – 1960-012A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Discoverer 15 – 1960-012A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b Ruffner, p. 32.

- ^ National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 52 Accessed 2012-06-06

- ^ Ruffner, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Day, Dwayne Allen (12 January 2009). "Ike's gambit: The KH-8 reconnaissance satellite". The Space Review. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "1967-043B". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "1967-043B". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "1970-098B". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "1970-098B". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. "The wizard war in orbit (part 4)". The Space Review. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Sturdevant, Rick. "From the Pied Piper Infrared Reconnaissance Subsystem to the Missile Defense Alarm System: Space-Based Early Warning Research and Development, 1955–1970". AIAA SPACE 2010 Conference & Exposition.

- ^ Yenne, Bill (1985). The Encyclopedia of US Spacecraft. Exeter Books (A Bison Book), New York. ISBN 978-0-671-07580-4. p. 37 Discoverer

- ^ Hammer, Emily; FitzPatrick, Mackinley; Ur, Jason (14 March 2022). "Succeeding CORONA: declassified HEXAGON intelligence imagery for archaeological and historical research". Antiquity. 96 (387): 679–695. doi:10.15184/aqy.2022.22. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Yenne, p. 63; Jensen, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f g Drell, "Physics and U.S. National Security", p. S462

- ^ Brown, Stewart F. "America's First Eyes in Space", Popular Science February 1996, p. 46

- ^ a b Brown, Stewart F., "America's First Eyes in Space", Popular Science February 1996, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b Peebles, p. 157

- ^ a b c d Olsen, p. 57

- ^ Yenne, p. 64

- ^ Smith, pp. 111–114

- ^ a b Lewis, p. 93

- ^ Monmonier, p. 24

- ^ Day, Logsdon, and Latell, pp. 192–196.

- ^ a b Ruffner, p. 37

- ^ a b Kramer, p. 354

- ^ Ruffner, pp. 34, 36

- ^ a b Ruffner, p. 36

- ^ a b Chun, p. 75

- ^ personal memoirs of Arthur R. Glines, CORONA program engineer, 1/1962 to 6/1967

- ^ a b Ruffner, p. 31

- ^ a b Drell, "Reminiscences of Work on National Reconnaissance", p. 42

- ^ Manaugh, Geoff (8 April 2014). "Zooming-In on Satellite Calibration Targets in the Arizona Desert". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Hider, Anna (3 October 2014). "What the heck are these abandoned cement targets in the Arizona desert?". Roadtrippers. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "CORONA Test Targets". borntourist.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Page II, Joseph T. (21 December 2020). "Candy CORN: analyzing the corona concrete crosses myth". The Space Review. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Peebles, p. 48.

- ^ Collins, p. 108

- ^ Hickam Kukini, p. A-4, Vol 15, No 48, Friday, 5 December 2008, Base newspaper from Hickam AFB

- ^ Monmonier, pp. 22–23

- ^ Monmonier, p. 23

- ^ a b Day, Dwayne Allen (18 February 2008). "Spysat down!". The Space Review. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Peebles, p. 159

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 58 Accessed 2012-06-06

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 58 Accessed 2012-06-06

- ^ Brown, p. 44; Burrows, p. 231

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "'Mission accomplished' for NRO at Onizuka AFS". USAF. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "'Mission accomplished' for NRO at Onizuka AFS". USAF. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Chronology of Air Force space activities" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Chronology of Air Force space activities" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "CIA Holds Landmark Symposium on CORONA". Federation of American Scientists. June 1995.

- ^ Peebles, p. 51

- ^ a b National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 154 Accessed 2012-06-06

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, The Corona Story, BYE 140001-98, December 1988, p. 32 Archived 2016-01-22 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2012-06-06

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, The Corona Story, BYE 140001-98, December 1988, p. 32 Archived 2016-01-22 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2012-06-06

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 118 Accessed 2012-06-06

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Reconnaissance Office, "National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide for Automatic Declassification of 25-Year-Old Information, Version 1.0, 2006 edition, p. 118 Accessed 2012-06-06

- ^ Chien, Phillip, "High Spies", Popular Mechanics, February 1996, p. 49

- ^ "2005 Draper Prize – Corona Historic Images". NAE Website.

- ^ Executive Order 12951

- ^ Broad, William J. (12 September 1995). "Spy Satellites' Early Role As 'Floodlight' Coming Clear". The New York Times.

- ^ "Satellite images spy ancient history in Syria". PhysOrg. 3 August 2006.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (7 August 2006). "Ancient Syrian Settlements Seen in Spy Satellite Images". LiveScience.

- ^ Ur, Jason. "Ancient Communication Networks in Northern Mesopotamia". Harvard University. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Ur, Jason. "Archaeological Applications of Declassified Satellite Photographs". Harvard University. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. (23 March 2009). "Battle's Laws". The Space Review.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "MISSION 9043 SUCCESSFUL AIR RECOVERY" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 21 September 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "MISSION 9043 SUCCESSFUL AIR RECOVERY" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 21 September 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Photographic Evaluation Report: Mission 9043" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 31 October 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Photographic Evaluation Report: Mission 9043" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 31 October 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Robery Perry (October 1973). "A History of Satellite Reconnaissance: Volume I – Corona (page 215)" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Robery Perry (October 1973). "A History of Satellite Reconnaissance: Volume I – Corona (page 215)" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2010.

- ^ "MEMO: PHOTOGRAPHIC RECONNAISSANCE SYSTEMS, PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES" (PDF). NRO. 5 September 1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Taubman, Secret Empire p. 287

Sources

- Burrows, William E., This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age, New York, Random House, 1998 [ISBN missing]

- Chun, Clayton K.S., Thunder Over the Horizon: From V-2 rockets to Ballistic Missiles, Westport, Praeger Security International, 2006 [ISBN missing]

- Collins, Martin, After Sputnik: 50 Years of the Space Age, New York, Smithsonian Books/HarperCollins, 2007 [ISBN missing]

- "Corona", Mission and Spacecraft Library, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, No date Accessed 2012-60-06

- Day, Dwayen A.; Logsdon, John M.; and Latell, Brian, eds. Eye in the Sky: The Story of the Corona Spy Satellites, Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998 ISBN 978-1560988304

- "Discoverer/Corona: First U.S. Reconnaissance Satellite". National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. 2002. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- Drell, Sidney D., "Physics and U.S. National Security", Reviews of Modern Physics, 71:2 (1999), pp. S460–S470

- Drell, Sidney D., "Reminiscences of Work on National Reconnaissance", in Nuclear Weapons, Scientists, and the Post-Cold War Challenge: Selected Papers on Arms Control, Sidney D. Drell, ed. Hackensack, New Jersey, World Scientific, 2007

- Jensen, John R., Remote Sensing of the Environment: An Earth Resource Perspective, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007 [ISBN missing]

- Kramer, Herbert J., Observation of the Earth and Its Environment: Survey of Missions and Sensors, Berlin, Springer, 2002 [ISBN missing]

- Lewis, Jonathan E., Spy Capitalism: Itek and the CIA, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-300-09192-3

- Monmonier, Mark S., Spying With Maps: Surveillance Technologies and the Future of Privacy, Chicago, Illinois, University of Chicago Press, 2004 [ISBN missing]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Societal Impact of Spaceflight, Washington, D.C., NASA, 2009

- Olsen, Richard C., Remote Sensing From Air and Space. Bellingham, Washington, SPIE Press, 2007

- Peebles, Curtis, The Corona Project: America's First Spy Satellites, Annapolis, Maryland, Naval Institute Press, 1997 [ISBN missing]

- Ruffner, Kevin C., ed. Corona: America's First Satellite Program, New York, Morgan James, 1995 [ISBN missing]

- Smith, F. Dow, "The Design and Engineering of Corona's Optics", in CORONA: Between the Sun and the Earth: The First NRO Reconnaissance Eye in Space, Robert McDonald, ed. Bethesda, Maryland: ASPRS, 1997

- Taubman, Phil, Secret Empire: Eisenhower, the CIA, and the Hidden Story of America's Space Espionage, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2003. ISBN 0-684-85699-9

- Yenne, Bill, Secret Gadgets and Strange Gizmos: High-Tech (and Low-Tech) Innovations of the U.S. Military, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Publishers Group Worldwide, 2006 [ISBN missing]

External links

- US Geological Survey Satellite Images: Photographic imagery from the CORONA, ARGON and LANYARD satellites (1959 to 1972).

- GlobalSecurity.org: Imagery Intelligence

- A Point in Time: The Corona Story is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Swords into Ploughshares: Archaeological Applications of CORONA Satellite Imagery in the Near East