Juhayman al-Otaybi

Juhayman al-Otaybi | |

|---|---|

جهيمان العتيبي | |

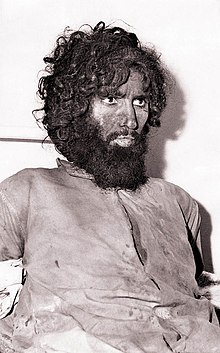

Juhayman in captivity, 1980 | |

| Born | 16 September 1936 Sajir, Saudi Arabia |

| Died | 9 January 1980 (aged 43) Mecca, Saudi Arabia |

| Cause of death | Decapitation |

| Alma mater | Islamic University of Medina |

| Occupation | Leader of the Ikhwan |

| Known for | Directing the Grand Mosque seizure in 1979 |

| Movement | Salafi Islamism/Islamic revivalism |

| Children | Hathal bin Juhayman al-Otaybi[1] |

| Family | Tribe of Otaibah |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | National Guard |

| Years of service | 1955–1973 |

Juhayman ibn Muhammad ibn Sayf al-Otaybi (Arabic: جهيمان بن محمد بن سيف العتيبي; 16 September 1936[2][3] – 9 January 1980) was a Saudi religious dissident and ex-soldier who led the Ikhwan during their Grand Mosque seizure in 1979. He and his followers besieged and took over the Grand Mosque of Mecca on 20 November 1979 (1 Muharram 1400) and held it for two weeks. During this time, he called for an uprising against the House of Saud and also reportedly proclaimed that the Mahdi had arrived in the form of one of the Ikhwan's leading officials; al-Otaybi's insurgency ended with Saudi authorities capturing the surviving militants and publicly executing them all, including al-Otaybi. The incident led to widespread unrest, culminating in large-scale anti-American riots throughout the Muslim world, particularly after Iranian religious cleric Ruhollah Khomeini of the Islamic Revolution claimed over a radio broadcast that Juhayman's insurgency at the holiest Islamic site had been orchestrated by the United States and Israel.[4][5][6]

Biography

Juhayman al-Otaybi was born in al-Sajir, Al-Qassim Province,[7] a settlement established by King Abdulaziz to house Ikhwan Bedouin tribesmen who had fought for him. This settlement (known as a hijra) was populated by members of his tribe, the 'Utaybah,[8] one of the most pre-eminent tribes of the Najd region.[9] Many of Juhayman's relatives participated in the Battle of Sabilla during the Ikhwan uprising against King Abdulaziz, including his father and grandfather, Sultan bin Bajad al-Otaybi. Juhayman grew up aware of the battle and of how, in their eyes, the Saudi monarchs had betrayed the original religious principles of the Saudi state.[10] He finished school without fluent writing ability, but he loved to read religious texts.[11]

He served in the Saudi Arabian National Guard from 1955[12] to 1973.[13][14] He was thin and 6'2 (188 cm) in height according to his friends in the National Guard. His son, Hathal bin Juhayman al-Otaybi, who works for the National Guard, was promoted to the rank of colonel in 2018.[15][16]

Education

Otaybi did not complete primary education, but he attended school until the fourth grade.[17] After his military service he moved to Medina.[13] There he attended religious courses at the Islamic University,[18] where he met with Muhammad ibn Abdullah Al Qahtani.[13]

Otaybi, upon moving to Medina, joined the local chapter of a Salafi group called Al-Jamaa al-Salafiya al-Muhtasiba (The Salafi group that commands right and forbids wrong), which was founded in the mid-1960s by several of Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani's disciples. Many of the group's members and scholars were either of Bedouin descent or non-Saudis residents, and therefore marginalized in the religious establishment. Their activism was at least partially motivated by this marginalization.[19] Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz[20] used his religious stature to arrange fundraising for the group, and Otaybi earned money by buying, repairing and re-selling cars from city auctions.[21][22]

Otaybi lived in a "makeshift compound" about a half hour's walk to the Prophet's Mosque, and his followers stayed in a nearby dirt-floored hostel called Bayt al-Ikhwan ("House of the Brothers"). Otaybi and his devotees obeyed an austere and simple lifestyle, searching the Quran and Hadith for scriptural evidence of what was permissible not only for their beliefs but in their day-to-day lives.[23] Otaybi was perturbed by the encroachment of Western beliefs and Bid‘ah (بدعة, innovation) in Saudi society to the detriment of what he believed to be true Islam. He opposed the integration of women into the workforce, television, the immodest shorts worn by football players during matches, and Saudi currency with an image of the King on it.[24][25]

By 1977, ibn Baz had departed to Riyadh and Otaybi became the leader of a faction of young recruits that developed their own—sometimes unorthodox—religious doctrines. When older members of the Jamaa travelled to Medina to confront Otaybi about these developments, the two factions split from each other. Otaybi attacked the elder sheikhs as government sellouts and called his new group Ikhwan—the name of a Wahhabi religious militia who first fought for the House of Saud in the 1920s against the Hashemites and then revolted against them in 1929.[26]

In the late 1970s, he moved to Riyadh, where he drew the attention of the Saudi security forces. He and approximately 100 of his followers were arrested in the summer of 1978 for demonstrating against the monarchy, but were released after ibn Baz questioned them and pronounced them harmless.[27][28]

He married both the daughter of Prince Sajer Al Mohaya[29] and the sister of Muhammad ibn Abdullah Al Qahtani.[13]

His doctrines are said to have included:[30]

- The imperative to emulate the Prophet's example—revelation, propagation, and military takeover.

- The necessity for the Muslims to overthrow their present corrupt rulers who are forced upon them and lack Islamic attributes since the Quran recognizes no king or dynasty.

- The requirements for legitimate rulership are devotion to Islam and its practice, rulership by the Holy Book and not by repression, Qurayshi tribal roots, and election by the Muslim believers.

- The duty to base the Islamic faith on the Quran and the sunnah and not on the equivocal interpretations (taqlid) of the ulama and on their "incorrect" teachings in the schools and universities.

- The necessity to isolate oneself from the sociopolitical system by refusing to accept any official positions.

- The advent of the Mahdi from the lineage of the Prophet through Husayn ibn Ali to remove the existing injustices and bring equity and peace to the faithful.

- The duty to reject those who associate partners with God (mushrikeen), particularly those who worship Ali, Fatimah and Muhammad.

- The duty to establish a puritanical Islamic community which protects Islam from unbelievers and does not court foreigners.

Insurgency

As his militants seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca and took hostages, Juhayman publicly denounced the House of Saud as corrupt and illegitimate, accusing the country's royals of pursuing alliances with "Christian infidels" and importing secularism into Saudi society.[31] The nature of his allegations echoed that of the charges that his father had brought against Ibn Saud in 1921. Unlike earlier anti-monarchy dissidents in Saudi Arabia, Juhayman directly attacked the country's ulama for failing to protest against Saudi government policies that betrayed Islam; he accused them of accepting the rule of an infidel state and of offering their loyalty to corrupt rulers "in exchange for honours and riches" amidst broader discontent against what he perceived as their un-Islamic teachings.[32]

Consisting of 300 to 600 well-organized militants under Juhayman's leadership, the Ikhwan took hostages from among the worshippers at the Grand Mosque and fought against the Saudi military's attempts to retake it, leading to approximately 800 casualties in total.[33] The Saudi government requested urgent aid from France, which responded by dispatching advisory units from the GIGN to the site. After French operatives provided them with a special type of tear gas that dulls aggression and obstructs breathing, Saudi troops gassed the interior of the Grand Mosque and successfully forced entry.[33] Juhayman was captured during the assault, sentenced to death by Saudi authorities, and subsequently executed by beheading on 9 January 1980.

References

- ^ "Mecca attacker Juhayman's son overcomes father's legacy, becomes Saudi colonel". Al Arabiya. 3 September 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Krämer 2000, p. 262.

- ^ Graham, Douglas F.; Peter W. Wilson (1994). Saudi Arabia: The Coming Storm. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 57. ISBN 1-56324-394-6.

- ^ Wright, Robin B. (2001). Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam. Simon & Schuster. p. 149.

- ^ [On 2 December 1979.] EMBASSY OF THE U.S. IN LIBYA IS STORMED BY A CROWD OF 2,000; Fires Damage the Building but All Americans Escape – Attack Draws a Strong Protest Relations Have Been Cool Escaped without Harm 2,000 Libyan Demonstrators Storm the U.S. Embassy Stringent Security Measures Official Involvement Uncertain, New York Times, 3 December 1979

- ^ Soviet "Active Measures": Forgery, Disinformation, Political Operations (PDF). Bureau of Public Affairs (Report). Washington, D.C., United States of America: United States Department of State. 1 October 1981. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Abir, Mordechai (1988). Saudi Arabia in the Oil Era: Regime and Elites Conflict and Collaboration. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-8133-0643-4.

- ^ Lacey 1981, p. 481; Ruthven, p. 8; Abir, p. 150

- ^ Lunn 2003: 945

- ^ Lacroix & Holoch 2011: 93

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Graham, Douglas F.; Peter W. Wilson (1994). Saudi Arabia: The Coming Storm. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 57. ISBN 1-56324-394-6.

- ^ a b c d "The Dream That Became A Nightmare" (PDF). Al Majalla. 1533. 20 November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2012.

- ^ Quandt, p. 94, gives 1972 as the date of his resignation; Graham and Wilson, ibid., say 1973; Dekmejian, p. 141, says "around 1974"

- ^ "Mecca attacker Juhayman's son overcomes father's legacy, becomes Saudi colonel". Al Arabiya. 3 September 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Son of Makkah Grand Mosque attacker becomes colonel in Saudi National Guards". Samaa TV. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Thomas Hegghammer; Stéphane Lacroix (February 2007). "Rejectionist Islamism in Saudi Arabia: The Story of Juhayman al-ʿUtaybi Revisited" (PDF). International Journal of Middle East Studies. 39 (1): 109. JSTOR 4129114.

- ^ David Commins (2006). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 164. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1010.4254.

- ^ Stéphane Lacroix (Spring 2008). "Al-Albani's Revolutionary Approach to Hadith". ISIM Review. 21: 6–7.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Dekmejian 1985, p. 143; Lacey 1981, p. 483; Krämer 2000, p. 262, p. 282 n. 17

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 12: "Everywhere Juhayman looked he could detect bidaa -- dangerous and regrettable innovations. The Salafi Group That Commands Right and Forbids Wrong was originally intended to focus on moral improvement, not on political grievances or reform. But religion is politics and vice versa in a society that chooses to regulate itself by the Koran. ... [other bidaa included] government making it easier for women to work .... immoral of the government to permit soccer matches, because of the very short shorts that the players wore ... use only coins, not banknotes, because of the pictures of the kings .... like television, a dreadful sin ..."

- ^ Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B.Tauris. p. 166.

As might be expected, a strict puritanical streak runs through Juhayman's writings on satanic innovations. Thus, to his mind, Islam forbids reproducing the human image. Likewise, he objected to the appearance of the king's likeness on the country's currency. As for the availability of alcohol, the broadcast of shameful images on television and the inclusion of women in the workplace, Juyhayman considered them all instance of Al Saud's indifference to upholding Islamic principles.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Lacey 1981, p. 483.

- ^ Graham & Wilson 1994, p. 57.

- ^ The Makkan Siege: In Defense of Juhaymān Archived 2015-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, p.7 pdf. A collection of internet articles.

- ^ Dekmejian 1985, p. 142.

- ^ Rubin, Elizabeth (7 March 2004). "The Jihadi Who Kept Asking Why". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B.Tauris. pp. 165–6.

- ^ a b Karen Elliott House, On Saudi Arabia: Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines, and Future, New York, New York: Alfred P. Knopf, 2012, p. 20

Works cited

- Abir, Mordechai (1988). Saudi Arabia in the Oil Era: Regime and Elites Conflict and Collaboration. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-0643-4.

- Dekmejian, R. Hrair (1985). Islam in Revolution: Fundamentalism in the Arab World. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2329-1.

- Graham, Douglas F.; Wilson, Peter W. (1994). Saudi Arabia: The Coming Storm. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-394-6.

- Lacroix, S., & Holoch, G. (2011). Awakening Islam: The Politics of Religious Dissent in Contemporary Saudi Arabia. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Krämer, Gudrun (2000). "Good Counsel to the King: The Islamist Opposition in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Morocco". In Joseph Kostiner (ed.). Middle East Monarchies: The Challenge of Modernity. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. pp. 257–287. ISBN 1-55587-862-8.

- Lacey, Robert (1981). The Kingdom. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-147260-2.

- Lacey, Robert (2009). Inside the Kingdom: Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia. Penguin Group US. ISBN 9781101140734.

- Lunn, John (2002). "Saudi Arabia: History". The Middle East and North Africa 2003 (49 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-132-2.

- Quandt, William B. (1981). Saudi Arabia in the 1980s: Foreign Policy, Security, and Oil. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. ISBN 0-8157-7286-6.

- Ruthven, Malise (2000). Islam in the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513841-4.

- Trofimov, Yaroslav (2007). The Siege of Mecca: The Forgotten Uprising in Islam's Holiest Shrine and the Birth of Al Qaeda. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51925-0.