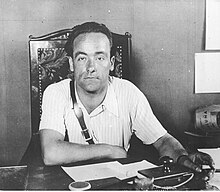

Juan García Oliver

Joan Garcia Oliver | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 4 November 1936 – 17 May 1937 | |

| President | Manuel Azaña |

| Prime Minister | Francisco Largo Caballero |

| Preceded by | Mariano Ruiz-Funes García |

| Succeeded by | Manuel de Irujo y Ollo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 January 1901 Reus, Baix Camp, Spain |

| Died | 13 July 1980 (aged 79) Guadalajara, Mexico |

| Political party | |

| Part of a series on |

| Syndicalism |

|---|

|

Joan Garcia Oliver (1901–1980) was a Catalan anarcho-syndicalist revolutionary and Minister of Justice of the Second Spanish Republic. He was a leading figure of anarchism in Spain.

Career

Childhood and family

Joan Garcia Oliver was born on 20 January 1901, in Reus, Baix Camp, into a working class family. He was the son of Antònia Oliver Figueras, a native of Reus, and José Garcia Alba, a native of Xàtiva. At that time, the family lived at 32 Carrer Sant Elias in the old town of Reus. Joan was the son of his father's second marriage, after being widowed, and he had four siblings, Elvira, Mercè, Pere and Antònia, and three half-siblings, Josep, Dídac and Lluïsa; but their step-siblings did not live with them, instead they lived in Cambrils.[1]

His brother Pere died of meningitis at the age of 7, when Joan was still very young. As a result the family had to go into debt and their mother had to start working on the street. When he was 7 years old, he was able to receive primary education for a few months. But, as a result of the birth of his sister Antònia and the beginning of a strike at the Vapor Nou where his father worked, he was forced to temporarily leave his studies and start working. He worked as a boy, earning one real a day in a small bag factory.[1] In spite of everything, Joan was able to resume his primary studies at the age of 8 in the school of the republican teacher Grau, after passing an entrance exam. His primary schooling finished when he turned 11 years old.[1]

As a young man, Joan Garcia worked in the wine trading house of Lluís Quer's widow, earning 5 pesetas a month, for three years. In the autumn of 1914, at the age of only thirteen and tired of routine work, he decided to escape to France in search of work; he had only a basic knowledge of French which he had learned self-taught. When he was near the border and without money, he realized that this had not been a good idea and returned to Reus. Later, he worked temporarily in several restaurants. First, at the La Nacional inn for 20 pesetas a month, then at the Sport Bar restaurant for a peseta a day and finally, at the Hotel Nacional de Tarragona for 50 pesetas a month. At the age of fifteen, he decided to move to Barcelona to find work and began working as a waiter at La Ibérica del Padre and later at the second-class inn Hotel Jardín.[1]

Social awareness

In Barcelona, the young Garcia Oliver was in a time of great social unrest and intense union struggle. Garcia Oliver experienced the general strike of 1917 as an observer; it was his second experience in a social conflict. Tired of his job as a waiter at the Hotel Jardín, he left and started working at the Las Palmeras bar-restaurant in the Boqueria market. He took a seasonal job as a waiter at the Colònia Puig de Montserrat in the spring of 1918 and, after completing it, at the Hotel Restaurant La Española in Carrer de la Boqueria, where he apprenticed as a cook. In this last job he began to attend the conferences of the Society of Waiters Alliance, that took place in the Cabanyes street.[2]

Anarcho-syndicalism

In 1919 he first joined the Society of Waiters L'Aliança, a member of the UGT, but later participated in the formation of the Union of the Hospitality Industry, Restaurants, Cafes and Annexes which was integrated into the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). Garcia Oliver later organized workers in Reus, led the CNT's provincial committee and was jailed during a strike action.

In 1922, he took part in the formation of the Los Solidarios direct action group which, in 1923, assassinated Cardinal Juan Soldevila y Romero in Zaragoza and General Secretary of the Sindicatos Libres Joan Laguía Lliteras in Manresa. Garcia Oliver subsequently worked as a polisher in France, where he unsuccessfully plotted to kill Alfonso XIII and Benito Mussolini. Upon his reentry to Catalunya in 1924, he was arrested in Manresa and imprisoned in Burgos, before being moved to Pamplona in 1926. He was released when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed and returned to Barcelona, where he joined the Iberian Anarchist Federation (Spanish: Federación Anarquista Ibérica, FAI). He is said to have invented the red and black flag of the CNT, which was first exhibited on 1 May 1931. He was secretary of the FAI and attended the third confederal congress of the CNT in Madrid from 10 to 16 June 1931, where he declared that it was necessary to launch into the revolution without waiting.

In 1932 he took part in the Alt Llobregat insurrection and was imprisoned again. He promoted the formation of the National Revolutionary Committee (which was based in Badalona) and led the January 1933 insurrection, which landed him back in prison. He was released after the electoral victory of the left in February 1936 elections. He participated in the IV Congress of the CNT in Zaragoza in May 1936, and anticipating the military uprising, he was part of the group that sought the supply of weapons. However, this project was not adopted because of the attitude of Federica Montseny and Diego Abad de Santillán, among others. After the July days of fighting in Barcelona, a plenary session of local and regional groups took place on 23 July. Garcia Oliver and the district of Baix Llobregat proposed the proclamation of libertarian communism, but there was unanimity against it. He promoted the formation of the Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia and organized the Harriers Column, which he marched with to the Aragon front. But he was called back to Barcelona to act as a representative of the CNT in the Committee, as the head of the War Department.[3]

On 4 November 1936, the CNT decided to join the war government of Francisco Largo Caballero, with Garcia Oliver acting as the Minister of Justice. He began organizing the "People's War Schools" and set up work camps for political detainees. In his tenure as minister, court fees were abolished and criminal records destroyed. In Barcelona there were a series of confrontations between revolutionary groups and the republican government, known as the May Days. Garcia Oliver urged the Barcelona CNT to abandon the struggle that had broken out in the streets, and called for a ceasefire. With the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, he settled in Sweden, Venezuela and finally Mexico. In 1978, two years before his death, Garcia Oliver published his autobiography, El eco de los pasos.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Alegret 2008, pp. 37–44.

- ^ Alegret 2008, pp. 45–57.

- ^ Massot i Muntaner, Josep (2002). Aspectes de la Guerra Civil a les Illes Balears (in Catalan). Josep Massot i Muntaner. p. 33. ISBN 8484153975.

- ^ Salvadó, Francisco J. Romero (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War. Scarecrow Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8108-8009-2.

Bibliography

- Abbate, Fulvio (2004). Il Ministro anarchico: Juan García Oliver un eroe della rivoluzione spagnola. Romanzi e racconti (in Italian). Milan: Baldini Castoldi Dalai. ISBN 9788884906144.

- Alegret, Lluís (2008). Joan Garcia Oliver: retrat d'un revolucionari anarcosindicalista. Testimonis (in Catalan). Barcelona: Pòrtic. ISBN 978-8498090499.

- Amorós, Miguel (2006). Durruti en el laberinto (in Spanish). Bilbao: Muturreko Burutazioak. ISBN 9788496044739.

- García Oliver, Juan (1978). El eco de los pasos (PDF) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Ibérica de Ediciones y Publicaciones. ISBN 84-85361-06-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011.

- My Revolutionary Life: Juan Garcia Oliver interviewed by Freddy Gomez. Anarchist Library series #19. Translated by Paul Sharkey. Kate Sharpley Library. 2008. ISBN 978-1-873605-72-1.

- Peirats, Jose (2011). Ealham, Chris (ed.). The CNT in the Spanish Revolution. Vol. 1. Oakland: PM Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-1-60486-207-2. OCLC 761890305.