Joshua Reed Giddings

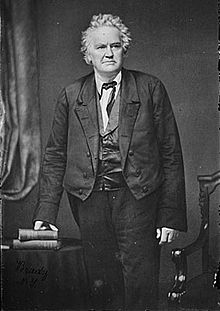

Joshua Giddings | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Mathew Brady | |

| Dean of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office March 4, 1855 – March 3, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Linn Boyd |

| Succeeded by | John S. Phelps |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio | |

| In office December 5, 1842 – March 3, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | John Hutchins |

| Constituency | 16th district (1842–1843) 20th district (1843–1859) |

| In office December 3, 1838 – March 22, 1842 | |

| Preceded by | Elisha Whittlesey |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| Constituency | 16th district |

| Member of the Ohio House of Representatives | |

| In office 1826–1827 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joshua Reed Giddings October 6, 1795 Tioga Point, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | May 27, 1864 (aged 68) Montreal, Canada |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (before 1834) Whig (1834–1848) Free Soil (1848–1854) Opposition (1854–1856) Republican (1856–1864) |

| Signature | |

Joshua Reed Giddings (October 6, 1795 – May 27, 1864) was an American attorney, politician and abolitionist. He represented Northeast Ohio in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1838 to 1859. He was at first a member of the Whig Party and was later a Republican, helping found the party.

Giddings is noted as a leading abolitionist of his era. He was censured in 1842 for violating the gag rule against discussing slavery in the House of Representatives when he proposed a number of Resolutions against federal support for the coastwise slave trade, in relation to the Creole case. He quickly resigned, but was overwhelmingly re-elected by his Ohio constituents in a special election to fill the vacant seat. He returned to the House and served a total of nearly twenty more years as representative.

Giddings is one of the main reasons that the Western Reserve was, before the Civil War, one of the most anti-slavery regions of the country.

Early life and education

Joshua Reed Giddings was born in Bradford County, Pennsylvania at Tioga Point, now Athens, on October 6, 1795.[1] His family moved that same year to Canandaigua, New York, where they spent the next ten years.[2]: xiv In 1806 his parents Elizabeth (née Pease) and Joshua Giddings moved the family to Ashtabula County, Ohio, which was then sparsely settled.[3] Here they settled on Ohio's Western Reserve, which "provided him with the occupational and social mobility so characteristic of the early nineteenth-century frontier",[2]: xiv where Giddings lived for most of the rest of his life. Many settlers from New England went there. As the Reserve was widely famous for its radicalism, Giddings may have been inspired in his first stirrings of passion for antislavery.

Giddings first worked on his father's farm and, although he received no systematic education, devoted much time to study and reading.[3] At 17 he joined a militia regiment for the War of 1812. He served for five months, including battles against American Indian allies of the British.

After 1814 Giddings was a schoolteacher. He married Laura Waters, daughter of a Connecticut emigrant, in 1819.[2]: xiv One of their children, Grotius Reed Giddings (1834–1867), was Major of the 14th United States Infantry in the American Civil War.

Giddings later read law with Elisha Whittlesey in preparation for a career as an attorney. He made some money through land speculation.[2]: xiv

Career

In February 1821 Giddings was admitted to the bar in Ohio. He soon built up a large practice, particularly in criminal cases. From 1831 to 1837 he was in partnership with Benjamin Wade, a future U.S. Senator.[3] Influenced by Theodore Weld, the two formed the local antislavery society.[2]: xv

Giddings and his friend Wade were both elected to Congress, where they were outspoken opponents of slavery throughout their careers. Wade was elected president of the Senate during the Andrew Johnson administration. He would have succeeded to the presidency of the United States had one more senator voted for the impeachment of Andrew Johnson.

Political career

Giddings was first elected to the Ohio House of Representatives, serving one term from 1826 to 1827.[4]

The Panic of 1837, in which Giddings lost a great deal of money, caused him to cease practicing law. He ran for federal office and was elected to Congress, "with instructions to bring abolition into national focus in any way possible".[2]: xvi Consistently re-elected to office, from December 1838 until March 1859, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing first Ohio's 16th district until 1843, and then Ohio's 20th district until 1859. Giddings ran first as a Whig, then as a Free-soiler, next as a candidate of the Opposition Party, and finally as a Republican. From 1838 until 1843, his district included the city of Youngstown. From 1843 to 1853, the boundaries were shifted northwest to include Cleveland and Youngstown was subtracted from his constituency; from 1853, Cleveland was again swapped for Youngstown.

For the start of the 1841 session Giddings and some of his colleagues, Seth M. Gates of New York, William Slade of Vermont, Sherlock J. Andrews of Ohio, and others, constituted themselves a Select Committee on Slavery, devoted to driving that institution to extinction by any parliamentary and political means, legitimate or otherwise. Not being an official committee, they met their operating expenses out of their own pockets. The expenses included the board and keep of Theodore Dwight Weld, the prominent Abolitionist lecturer, who researched and helped prepare the speeches by which the members excited public opinion against slavery at every opportunity. Their headquarters was in Mrs. Sprigg's boarding-house, directly in front of the Capitol, where Gates, Slade, Giddings, Weld, and the influential abolitionist minister Joshua Leavitt, lived during sessions of Congress; others gradually joined them.[5][2]: xvi John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts was not a member of the committee, but acted as a powerful ally.

Giddings found an early opportunity to attack slavery when on February 9, 1841, he delivered a speech upon the Seminole War in Florida, insisting that it was waged in the interest of slavery.[6]

In the Creole case of 1841, American slaves had revolted and forced the brig Creole into Nassau, Bahamas, where they gained freedom as Britain had abolished slavery in its territories in 1834.[7] Southern slaveholders argued for the federal government to demand the return of the slaves or compensation.

Giddings emphasized that slavery was a state institution, with which the Federal government had no authority to interfere; he noted that slavery only existed by specific state enactments. For that reason, he contended that slavery in the District of Columbia and in the Territories was unlawful and should be abolished, as these were administered by the federal government. Similarly, he argued that the coastwise slave trade in vessels flying the national flag, like the international slave trade, should be rigidly suppressed as unconstitutional, as the states had no authority to extend slavery to ships on the high seas, and the federal government had no separate interest in it. He also held that Congress had no power to pass any act that in any way could be construed as a recognition of slavery as a national institution.[3]

His statements in the Creole case attracted particular attention, as he had violated the House's gag rule barring antislavery petitions.[7]

The U.S. government attempted to recover the slaves from the Creole, initiating an international scuffle with Britain.[7] Daniel Webster, then U.S. Secretary of State under President John Tyler, asserted that as the slaves were on an American ship, they were under the jurisdiction of the U.S., and by U.S. law they were property.[7]

On March 21, 1842, before the case was settled, Giddings introduced a series of resolutions in the House of Representatives. He asserted that in resuming their natural rights of personal liberty, the slaves violated no law of the U.S.[8] He contended the U.S. should not try to recover them, as it should not take the part of a state. For offering these resolutions, Giddings was attacked by numerous critics. The House formally censured him for violating the gag rule, and he was not permitted to speak in his own defense.[7] He resigned, appealing to his constituents, who immediately reelected him by an overwhelming margin of 7,469 to 383 in the special election to fill his seat.[9] That was the widest margin of victory that had ever been achieved in a contest for a seat in the House of Representatives, in any Congress. The House abandoned any thought of disciplining Giddings, and his colleagues on the Select Committee on Slavery discovered that his impunity extended to them.[10] With increasing anti-slavery agitation, the House repealed its "gag rule" three years later on December 3, 1844.

Giddings' daughter Lura Maria, an active Garrisonian, convinced her father to attend the meetings held by Garrison's followers, which heightened his anti-slavery position. William Lloyd Garrison was a spiritual as well as political leader. In the 1850s Giddings also adopted other progressive ideas, identifying with perfectionism, spiritualism, and religious radicalism. He claimed that his antislavery sentiments were based on a higher natural law, rather than just on the rights of the Constitution. Giddings called the caning of Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate by an opponent a crime "against the most vital principles of the Constitution, against the Government itself, against the sovereignty of Massachusetts, against the people of the United States, against Christianity and civilization." Many of these views were reflected in his noted "American Infidelity" speech of 1858.

Giddings often used violent language, and did not hesitate to encourage bloodshed. He talked about the justice of a slave insurrection and the duty of Northerners to fully support such an insurrection. He opposed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and advised escaping slaves to shoot at their potential captors.

Giddings led the Congressional opposition by Free State politicians to any further expansion of slavery to the West. Accordingly, he condemned the annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas–Nebraska Act, all of which contributed to expansion of slavery in the West. Following the war with Mexico, Giddings cast the only ballot against a resolution of thanks to General Zachary Taylor.

With increasing political activism related to slavery, Giddings shifted from the Whig party to the Free Soil Party, "which undoubtedly cost him a seat in the United States Senate", with the Whigs opposing him.[2]: xviii In 1854–55, he became one of the leading founders of the Republican party. Giddings campaigned for John C. Frémont and Abraham Lincoln, although Giddings and Lincoln disagreed over the uses of extremism in the anti-slavery movement. Before the Civil War, he helped support the Underground Railroad to help fugitive slaves reach freedom. He was widely known (and condemned by some) for his egalitarian racial beliefs and actions.

On the eve of the war, a Virginia newspaper offered $10,000 for his seizure and shipment to Richmond, or $5,000 for his head alone.[2]: xxii

In 1859 he was not renominated by the Republican Party to Congress. Giddings retired from Congress after a continuous service of more than twenty years.[11] In 1861 he was appointed by Lincoln as U.S. consul general in Canada, and served there until his death at Montreal on May 27, 1864.[12] He is buried at Oakdale Cemetery in Jefferson, Ohio.

Honors and legacy

Joshua R. Giddings Elementary School in Washington, DC was constructed in 1887 and named in his honor.[13] It closed in the 1990s and now is a sports club and gym.[14]

His law office in Jefferson, Ohio has been preserved as a National Historic Landmark.[15]

A life-size bronze depiction of Giddings is featured inside the Cuyahoga County Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument.[16]

Published works

- Giddings, Joshua R. (c. 1842). Pacificus: The Rights and Privileges of the Several States in Regard to Slavery. being a series of essays, published in the Western Reserve Chronicle, (Ohio) after the election of 1842.

- Giddings, Joshua R. (1842). An expose of the circumstances which led to the resignation by the Hon. Joshua R. Giddings of his office of representative in the Congress of the United States, from the sixteenth Congressional district of Ohio, on the 22d March, 1842.

- Giddings, Joshua R. (c. 1844). The rights of the free states subverted, or, An enumeration of some of the most prominent instances in which the federal Constitution has been violated by our national government, for the benefit of slavery, by a Member of Congress. Enumeration of some of the most prominent instances in which the federal constitution has been violated by our national government for the benefit of slavery. pp. 16 pages. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Speeches in Congress (1853)

- Giddings, Joshua R. (1858). The Exiles of Florida: or, The Crimes Committed by Our Government against the Maroons, who Fled from South Carolina and other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Laws. Follett, Foster and Company. Retrieved May 8, 2018. Reprinted with introduction by Arthur Thompson, University of Florida Press, 1964.

- History of the Rebellion: Its Authors and Causes (1864).

Archival material

The Indiana State Library has a collection of his correspondence and memoirs. "The collection consists primarily of memoirs of Joshua R. Giddings. Also included are family correspondence (mainly between father and daughter Laura Giddings), journal entries by the elder Giddings, diaries of Laura, photographs, and a biography of Giddings by his daughter."[17]

See also

- Joshua R. Giddings Law Office National Historic Landmark

- List of United States representatives expelled, censured, or reprimanded

Notes

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. II. James T. White & Company. 1921. p. 329. Retrieved May 9, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Thompson, Arthur W. (1964). "Introductory". The Exiles of Florida. By Giddings, Joshua. University of Florida Press.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 1.

- ^ Ohio General Assembly (1917). Manual of legislative practice in the General Assembly. State of Ohio. p. 262.

- ^ Barnes, Gilbert Hobbs, The Anti-Slavery Impulse 1830–1844. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, etc., 1933, 1964, pp. 177–190.

- ^ Gilman, Peck & Colby 1906.

- ^ a b c d e "The House Censured Rashida Tlaib for Political Speech Plain and Simple". Esquire. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Gerald Horne, Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation, New York University (NYU) Press, 2012, p. 137

- ^ Barnes, Gilbert Hobbs, The Anti-Slavery Impulse 1830–1844. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, etc., 1933, 1964, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 2.

- ^ "Hon. Joshua R. Giddings". Brooklyn Times-Union. May 28, 1864. p. 2. Retrieved May 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harris, Gabriela (May 2008). "Historic Schools in Washington, DC: Preserving a Rich Heritage". Digital Repository at the University of Maryland. University of Maryland: 31–33.

- ^ Cinelli, Pattie (April 13, 2017). "The New Sport & Health". Hill Rag.

- ^ "Giddings, Joshua Reed, Law Office". National Register Digital Assets. National Park Service. May 30, 1974.

- ^ Pacini, Lauren R. (2019). Honoring their memory : Levi T. Scofield, Cleveland's monumental architect and sculptor. Cleveland [Ohio]. ISBN 978-0-578-48036-7. OCLC 1107321740.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Indiana State Library. "Giddings, Joshua R. (finding aid)". Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giddings, Joshua Reed". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. This work in turn cites:

- Buel, Joshua R. Giddings (Cleveland, 1882)

- Julian, George Washington, Life of Joshua R. Giddings (Chicago, 1892). Julian was his son-in-law.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1906). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

References

- Julian, George Washington. The Life of Joshua R. Giddings, A.C. McClurg & Company, 1892

- Stewart, James Brewer, Joshua R. Giddings and the Tactics of Radical Politics, (Cleveland, 1970).

Further reading

- Julian, George W. (1892). "The Life of Joshua R. Giddings". A.C. McClurg.

- Ludlum, Robert P. (1936). Joshua R. Giddings, Antislavery Radical (1795-1844). Ph.D. diss., Cornell University.

- Solberg, Richard W. (1952). Joshua Giddings, Politician and Idealist. Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

- Stewart, James Brewer (1970). Joshua R. Giddings and the Tactics of Radical Politics. Press of Case Western Reserve University. ISBN 9780829501698.

- Gamble, Douglas A. (Winter 1979). "Joshua Giddings and the Ohio Abolitionists: A Study in Radical Politics". Ohio History. 88: 37–56.

External links

- Works by Joshua Reed Giddings at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Joshua Reed Giddings at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Joshua Reed Giddings at the Internet Archive

- United States Congress. "Joshua Reed Giddings (id: G000167)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Joshua Reed Giddings at Find a Grave