José María de Torrijos y Uriarte

José María de Torrijos y Uriarte | |

|---|---|

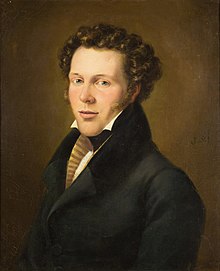

José María Torrijos in a portrait by Ángel Saavedra | |

| Born | March 20, 1791 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | December 11, 1831 Málaga, Spain |

| Allegiance | Spain |

| Rank | General |

| Battles / wars | Spanish War of Independence |

| Awards | Earl of Torrijos, posthumously Count of Torrijos {posthumously) |

Jose Maria Torrijos y Uriarte (March 20, 1791 – December 11, 1831), Count of Torrijos, a title granted posthumously by the Queen Governor, also known as General Torrijos, was a Spanish Liberal soldier. He fought in the Spanish War of Independence and after the restoration of absolutism by Ferdinand VII in 1814 he participated in the pronouncement of John Van Halen of 1817 that sought to restore the Constitution of 1812, for which he spent two years in prison until he was released after the triumph of the Riego uprising in 1820. He returned to fight the French when the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis invaded Spain to restore the absolute power of Ferdinand VII and when those triumphed ending the liberal triennium exiled to England. There he prepared a statement which he himself led, landing on the coast of Málaga from Gibraltar on December 2, 1831, with sixty men accompanying him, but they fell into the trap that had been laid before him by the absolutist authorities and were arrested. Nine days later, on December 11, Torrijos and 48 of his fellow survivors were shot without trial on the beach of San Andres de Málaga, a fact that was immortalized by a sonnet of José de Espronceda entitled To the death of Torrijos and his Companions, Enrique Gil y Carrasco's A la memoria del General Torrijos, and by a well-known 1888 painting by Antonio Gisbert. "The tragic outcome of his life explains what has happened to history, in all fairness, as a great symbol of the struggle against despotism and tyranny, with the traits of epic nobility and serenity typical of the romantic hero, eternalized in the famous painting by Antonio Gisbert."[1] The city of Málaga erected a monument to Torrijos and his companions in the Plaza de la Merced, next to the birthplace of the painter Pablo Picasso. Under the monument to Torrijos in the middle of the square are the tombs of 48 of the 49 men shot; One of them, British, was buried in the English cemetery (Málaga).

Biography

Childhood and youth

Torrijos was born March 20, 1791, in Madrid to a family of Andalusian bureaucrats in the service of the Monarchy. He was the third of four children born to Cristóbal de Torrijos and Chacón, of Seville, and Maria Petronila Uriarte and Borja, in El Puerto de Santa María. His paternal grandfather, Bernardo de Torrijos, was from Málaga, and belonged to the Royal Council and was prosecutor of the Royal Chancery of Granada. His father was knight of the Order of Carlos III and valet of the King Carlos IV. Thanks to the position he held, Jose Maria served ten years as the King's page. He immediately decided on a military career and, at the age of thirteen, he entered the Academy of Engineers where he specialized in engineering. [2]

War of Independence (1808–1814)

Torrijos participation in the War of Independence began the same day that the war began, May 2, 1808. He came to the aid of the officers Luis Daoiz and Pedro Velarde who were out of ammunition in the artillery park of Madrid. They sent him to negotiate with the French general Gobert but in the middle of the mission, the popular anti-French revolt erupted in the capital and so he was arrested. He was only saved from being shot by the intervention of a field helper who knew Joaquin Murat. At that time he was seventeen and had the rank of captain. [3]

He later joined the defence of Valencia, Murcia and those of Catalonia, being "one of the few military cadres of the old army who put themselves at the head of the national resistance in the name of the liberal principles of freedom and independence. He detached himself from the French and collaborationist camp chosen by many illustrated and clearly confronted with absolutism. " In 1810, at nineteen years old, he reached the rank of lieutenant colonel. He was taken prisoner by the French, after being wounded, but escaped and returned to fight in the war, "consecrating like a military of great boldness and value". He was appreciated by the two sides – the French general Suchet offered him the chance to defect, and the British Doyle asked of the Cortes of Cadiz that he be given a distinguished command in the reorganised forces in the Island of Leon. It was under the orders of the Duke of Wellington in the decisive Battle of Vitoria, that was going to lead to the end of the war. Three months earlier, in March 1813, he had married Luisa Carlota Sáenz de Viniegra, daughter of an honorary intendant of the army, with whom he had a daughter in 1815 who died shortly after birth. [4] Torrijos ended the war with the rank of brigadier general at only twenty-three years of age.

Failed plot against Ferdinand VII and prison (1817–1820)

After the return of Ferdinand VII and the restoration of the Absolute Monarchy in 1814, Torrijos was appointed military governor of Murcia, Cartagena and Alicante, receiving in 1816 the Great Cross of San Fernando for his military merits. But Torrijos soon became involved in the liberal conspiratorial plot that was intended to end at last the absolute power of the king and reinstate the Constitution of Cadiz. In order to do so he apparently joined the Masonry by adopting the name "Aristogiton." [5]

The conspiracy in which he participated directly was led by Juan Van Halen, which was going to take place in the area under his command. He engaged in the attempt to enlist Lorraine who was in charge, with the help of his friend the Lieutenant Colonel Juan López Pinto, and contacted various clandestine liberal groups in his territory. But Torrijos was discovered and detained on December 26, 1817, first imprisoned in the Santa Barbara Castle Alicante and then in the prison of the Inquisition of Murcia. There he spent the next two years, although he did not give up conspiratorial activity thanks to his wife who visited him in jail and sent him the clandestine papers, as she narrated herself, " either putting the papers inside the bones of the flesh , or in the handles of the silverware or in the hem of the tablecloths and napkins. " For his part Van Halen escaped in 1818 from the prisons of the Holy Office.

The liberal triennium (1820–1823)

He left the prison thanks to the triumph of the Rafael del Riego uprising that on February 29, 1820, led to the proclamation of the Constitution of 1812 in Murcia. King Fernando VII, after being forced to accept the Constitutional Monarchy, tried to attract Torrijos to his side and offered to transfer him to Madrid with the position of colonel of the regiment that bore his name, but Torrijos flatly refused. Which was worth the marginalization of any responsibility on the part of the "moderate" liberal governments. [6]

He supported the patriotic societies defended by the liberals "exaltados" and was inducted in June 1820 into the famous Fontana de Oro and in the Lovers of the Constitutional Order. Torrijos and other "exalted" Liberals created a secret society known as La Comunería, whose purpose was to defend the Constitution, and which shortly before the end of Trienio was split between a "radical" sector linked to the newspaper "Zurriago" and that of the "constitutional comuneros", of which Torrijos was a part. [6]

When the royalist uprisings took place, Torrijos participated in the war against the royalist parties in Navarre and in Catalonia – where he was the lieutenant of General Francisco Espoz y Mina -, which earned him the promotion to Field Marshall by order of the "exalted" government of Evaristo San Miguel. Shortly thereafter, on February 28, 1823, he was appointed Minister of War but failed to take office when the king revoked the "exalted" government of which Torrijos was a part. [7]

When in May 1823 the invasion of the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis sent by the Holy Alliance to restore the absolute power of the King Ferdinand VII, acted under the orders of general Ballesteros. But this, so that Torrijos did not bother him in his intended maneuver of not offering any resistance to the enemy, sent it destined for Cartagena to the control of the VIII military District. There he defended the plaza along with Francisco Valdés and Juan López Pinto until a month after the government and the Cortes had capitulated before the Duke of Angoulême in September Of 1823 after the fall of the fort Trocadero of Cadiz, which ended up giving the name to a celebrated square of Paris. Thus Torrijos in Cartagena, along with Espoz y Mina in Barcelona, were the last military that resisted. In the act of surrender to the French troops signed on November 3, 1823-it had been a month since Ferdinand VII had restored absolutism-Torrijos got the officers who went into exile to collect their salaries in the emigration, according to their condition of Refugees, not political prisoners. "It surrendered with all the honors: the arms were seized, but no one was shot, neither were prisoners nor reprisals. In the few days, on November 7, 1823, Rafael del Riego was Executed on the Plaza de la Cebada in Madrid, was the sad symbol of the defeat of the liberals at the hands of the Holy Alliance, and on November 18 Torrijos and his wife embarked for Marseilles, where they arrived on 1 December. Thus began an exile that would irreversibly change their lives."[8]

Exile in England (1824–1830)

In France he stayed only five months because of the hostility shown by his government to the Spanish liberal exiles, who were heavily guarded by the police and who were not allowed to reside in the border departments with Spain. At that time Torrijos claimed for him and for his subordinates the salary stipulated in the agreement of surrender of Cartagena which the government refused to pay (they only collected after the revolution of 1830, triumphed in France) – and entered in Contact with the general Lafayette, deputy and one of the main leaders of the liberal opposition to the Monarchy of Louis XVIII, with which it maintained an active correspondence of the one that created a long friendship.[9]

On April 24, 1824, Torrijos and his wife embarked for England and during the first two years lived in a modest house of Blackheath until at the end of 1826 they moved to London. During that time he lived on the help of his former boss the Duke of Wellington, then British Prime Minister, which held until July 1829 when he was withdrawn because of the increase in his conspiratorial activity. As this grant was not very large he had to devote work to translation. Thus he translated from French into Castilian the Napoleon's Memories, preceded by an introduction – in which he showed his admiration for Bonaparte as a forger of a "national" army, among other reasons – and supplemented by numerous notes, and from English into Spanish the "Memoirs of General Miller," who had participated in the Peruvian war. Torrijos had personally met General Miller in 1812 during the campaigns of the Spanish War of Independence. In the prologue of the latter Torrijos emphasized that Miller had left his land to fight for the freedom "of South America", without even knowing the language, and that "it always served to the homeland that had adopted, doing as it should abstraction of people and matches. "[10]

A few months after going to live in London, the most radical Spanish liberal exiles created on 1 February 1827 a "Board of the uprising in Spain" that was presided over by Torrijos, thus becoming the top leader of this liberal sector " Exalted "who had distanced himself from the more moderate positions of Francisco Espoz and Mina, who until then had been the leader of liberals exiled in England and who at the time was quite skeptical about the chances of success of a pronouncement in Spain against the absolutism of Fernando VII. [11]

The pronouncement of 1831

In May of 1830 Torrijos presented his plan for the insurrection consisting in the penetration "in circumference" in the Peninsula to attack the center, Madrid, from several points, which would begin the "break", that is to say, the entrance in Spain of the conspirators in London led by himself would be the signal for the uprising. On July 16, 1830, the Board of London was dissolved. Appointed on an interim basis until the nation was "freely assembled" an Executive Commission of the uprising was created led by Torrijos himself, as the chief military officer, and by Manuel Flores Calderón, former president of the Cortes del Trienio Liberal as a civil authority. Torrijos and his followers arrived in Gibraltar at the beginning of September via Paris and Marseilles. In Gibraltar they remained for a whole year until the end of November 1831, and from there Torrijos promoted several insurrectional conquests in February and March 1831, which were answered by a brutal repression of the absolutist government of Ferdinand VII, whose most famous victim was Mariana Pineda, executed in Granada the 26 of May of that year. [12]

In September 1831 the captain general of Andalusia proposed to the government "to seize the revolutionary caudillo Torrijos by surprise or stratagem". The main protagonist of this would be the governor of Málaga, Vicente González Moreno, who from the previous month had initiated an active correspondence with Torrijos under the pseudonym of Viriato, posing as a liberal who assured him that the best place for the landing would be the coast of Málaga, where he would have secured the support of the garrisons and where all the liberals were willing to second him."[13]

Unfortunately Torrijos paid more attention to Viriato, and to some genuine liberals who also wrote him encouraging him, than to the Junta de Málaga that tried to dissuade him from landing on those shores if he did not have enough forces. [14]

On November 30, two boats with sixty men headed by Torrijos, who were sufficient for the project since the landing did not have a military character, only intended to tread Spanish land and "pronounce", which would constitute the "break" that would trigger the Liberal uprising throughout Spain. They had printed a Manifesto to the Nation, in addition to several proclamations. "As symbolic elements, uniforms, tricolor flags (red and yellow, with two blue-blue stripes) and emblems with arms of Spain. Their mottos:" Patria, Libertad e Independencia ", and the cry of" Long live the freedom! "[15]

On the morning of December 2, they saw the city of Málaga, after almost forty hours of travel. Arriving at the coast they were surprised by the ship Neptune , which opened fire on the liberals. With no more shelter than the land itself, Torrijos and his men hurried to the beach of El Charcón. Then the group of Torrijos began its way towards the Sierra de Mijas. When they were near the town of Mijas they saw formations arranged to cut off their passage and to capture them and the men Torrijos orders in that border the town. After several days of walking, they descended along the north slope of the Sierra de Mijas and enter the Guadalhorce valley towards Alhaurín de la Torre, located twenty kilometers from Málaga. They took refuge in Torrealquería of the Count of Mollina in Alhaurín de la Torre. With the first light of day December 4, 1831, Realist Volunteers fired their weapons to indicate that the liberals had been located and were surrounded. Then the attack began. The Liberals, for their part, opened fire from within. Torrijos finally decided to surrender and hope that in Málaga the course of events had changed.

The group was taken prisoner and marched to the Convent of San Andrés (Málaga) | Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos de San Andrés, where they spent their last hours. At 11:30 in the morning on Sunday 11 December, Torrijos and his 48 companions were executed.[16] A monument honors the memory of the companions who were shot with General Torrijos. They were shot without trial in two groups on the San Andrés beach of Málaga.[17] "In the first one was Torrijos, who was not allowed to send for the execution squad, as he had requested." [18]

References

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 77.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Castells 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 85, 89.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 94.

- ^ Castells 2000, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 95.

- ^ "Cementerio Histórico de San Miguel". Archived from the original on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- ^ Torrijos and his comrades 'return' to San Andrés[permanent dead link] », 7 / 12/2009.

- ^ Castells 2000, p. 96.

Bibliography

- Castells, Irene (2000). "José María Torrijos (1791-1831). Conspirador romántico". Liberales, agitadores y conspiradores. Biografías heterodoxas del siglo. Burdiel. ISBN 84-239-6048-X.

- Del Pino Chica, Enrique (2001). Editorial Alhulia (ed.). Retama Field. ISBN 8495136759.

External links

- Moreno Espinosa, Alfonso (1915). Compendio de historia de España, distribuído en lecciones y adaptado á la índole y extensión de esta asignatura en la segunda enseñanza (in Spanish). Tipografia el Anuario de la exportacion. p. 483. Retrieved June 23, 2022.