John Mervin Nooth

John Mervin Nooth[note 1] FRS (5 September 1737 – 3 May 1828) was an English physician, scientist, and army officer. Nooth earned his medical degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1766 and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1774. In the same year, inspired by Joseph Priestley's work on "fixed air" (now known as carbon dioxide), Nooth invented an instrument for producing carbonated water. The Nooth apparatus, as it came to be called, became popular for household use; the liquid it produced was thought to have medicinal properties. Modified versions of the Nooth apparatus were used in commercial beverage manufacturing and in early experiments with general anaesthesia. Nooth joined the British Army in 1775 and served in North America until 1784, becoming superintendent-general of the British military hospitals in 1779. In 1788 he was deployed to Quebec; he remained in Canada until 1799 and became involved in scientific and political pursuits there. On his return he settled in Bath, England, where he lived until his death.

Early life and education

Nooth was born into an affluent family on 5 September 1737 in Sturminster Newton, Dorset. His father, Henry Nooth, was an apothecary and his mother, Bridget, was an apothecary's daughter. Nooth attended the University of Edinburgh, graduating with a medical degree in 1766. Following his graduation, he carried out independent research and spent a year travelling Europe,[2][3] later settling in London. Nooth's scientific work brought him into contact with Benjamin Franklin, to whom he wrote in 1773 to propose improvements to a machine for generating static electricity. His letter to Franklin was read at the Royal Society of London,[4] and with Franklin's endorsement, among others', Nooth was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1774.[2]

The Nooth apparatus

In December 1774, Nooth's paper entitled "The description of an apparatus for impregnating water with fixed air" was read at the Royal Society. The paper described an instrument used to produce carbonated water (carbon dioxide, at the time, was referred to as "fixed air"). The apparatus consisted essentially of three stacked glass vessels. Carbon dioxide was generated in the bottom vessel by the action of diluted sulfuric acid on pieces of chalk or marble. It diffused through a valve into the middle vessel, which contained the liquid to be carbonated. Liquid displaced by the gas collected in the topmost vessel.[4][5]

The instrument, which later came to be known as the Nooth apparatus, was based on one previously built by Joseph Priestley. Nooth argued that his device was superior because it was easier to use and, unlike Priestley's which used an animal bladder to contain the "fixed air", did not cause the water to taste of urine. Priestley took Nooth's criticism poorly at first;[4] in the second volume of his Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air, he retorted that "when the Doctor shall once more produce this urinous flavour [...] taking care that no careless servant shall have mixed any urine in the water he calls for, I shall give this new objection to my process a farther examination. At present I am inclined to consider this as an experiment of the servant, rather than of the Doctor himself."[6] However, he would eventually come to recommend Nooth's apparatus over his own.[4]

At the time, carbonated drinks were valued more for their supposed medicinal qualities than for their taste, and it was this application that led Nooth to invent his apparatus. David Macbride had recently posited that "putrefactive" conditions—a classification that referred mainly to what are now recognised as infections, but which also included scurvy—were caused by a loss of "fixed air". Drinking water impregnated with the gas therefore seemed like a sensible treatment.[note 2] The ability of carbon dioxide to dissolve some bladder stones under laboratory conditions led researchers to speculate that carbonated water would have the same effect when consumed. The Nooth apparatus could also be used to simulate natural mineral waters, which were believed to have curative properties.[4]

Nooth's apparatus became a popular household implement and was sold worldwide.[4] In the late 1770s, Thomas Henry used a device based on the apparatus to manufacture carbonated water at a commercial scale for the first time,[7] though Johann Jacob Schweppe's design would later come to be favoured over Nooth's for this purpose.[5] The Nooth apparatus remained in production until 1831, but it is unclear how many intact examples survive today.[5]

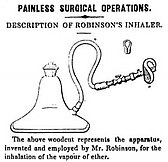

The apparatus later found another purpose, as modified versions were used to administer ether in some of the earliest experiments with general anaesthesia.[4] In 1846 the dentist James Robinson used a device incorporating the bottom of a Nooth apparatus to deliver general anaesthesia for the first time in Britain;[8] not long afterwards, Peter Squire, working with Robert Liston, devised an improved inhaler based on Robinson's design, which was successfully used to anaesthetise a patient during an amputation. These devices quickly fell out of favour, however, because they were fragile and awkward to use.[9]

Military career and later life

Nooth joined the British Army and was appointed Physician Extraordinary and Purveyor to the troops in North America in 1775. Around this time he married Sarah Williams; the couple had three children.[2] Nooth served through the American Revolutionary War, becoming superintendent-general of the British military hospitals in America in 1779, and returned home in 1784. Four years later he was deployed to serve at the hospitals in Quebec (in the meantime he had developed an artificial respiration device). While in Canada, Nooth became involved in politics and continued his scientific and medical pursuits, corresponding frequently on these subjects with Joseph Banks. He was named director of the Agriculture Society of Quebec in 1790. In 1798, Nooth treated Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn after a horse riding accident;[3] he was later appointed physician to his household, serving in that position until the duke's death.[2][3]

In 1799, Nooth's declining health led him to return to London.[3] Not long after his arrival, he had a coughing fit during which he expelled a lead bullet. His symptoms quickly improved, and he published a paper describing these events in the Transactions of a Society for The Improvement of Medical and Chirurgical Knowledge.[4] He resumed his military service in 1804, serving in Gibraltar until 1807; his wife died there in 1804. On his return, he settled in Bath, England, and married Elizabeth Willford.[2] He died in Bath on 3 May 1828.[3]

Notes

References

- ^ Zuck, D (1993). "John Mervyn Nooth". Anaesthesia. 48 (8): 712–714. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07187.x. ISSN 0003-2409. PMID 8214464. S2CID 40557126.

- ^ a b c d e Scott, EL (2004). "Nooth, John Mervin". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40498. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e Roland, CG (1987). "Nooth, John Mervin". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. VI (1821–1835) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Zuck, D (1978). "Dr. Nooth and His Apparatus: The role of carbon dioxide in medicine in the late eighteenth century". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 50 (4): 393–405. doi:10.1093/bja/50.4.393. ISSN 0007-0912. PMID 350247.

- ^ a b c McCloughlin, Thomas J.J. (2021). "Lost and found: The Nooth apparatus". Endeavour. 45 (1–2): 100763. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2021.100763. ISSN 0160-9327. PMID 33784551.

- ^ Priestley, J (1775). Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. Vol. 2. pp. 296–7.

- ^ a b Steen, D; Ashurst, PR (15 April 2008). Carbonated Soft Drinks: Formulation and Manufacture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-4051-7170-0.

- ^ Ellis, RH (1992). James Robinson, England's true pioneer of anaesthesia. Proceedings of the third international symposium on the history of anaesthesia. Atlanta, Georgia.

- ^ Masson, AHB (1989). "Two early ether inhalers". Anaesthesia. 44 (10): 843–846. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1989.tb09106.x. ISSN 0003-2409. PMID 2686482. S2CID 19468585.

Further reading

- Nooth, JM. "To Benjamin Franklin from John Mervin Nooth, [before 22 April 1773]: extract". Letter to Franklin, B.

- Nooth, JM (1775). "The description of an apparatus for impregnating water with fixed air; and of the manner of conducting that process". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 65: 59–66. doi:10.1098/rstl.1775.0005. ISSN 0261-0523.

- Nooth, JM (1804). "Case of a disease of the chest from a leaden shot accidentally passing through the glottis into the trachea". Transactions of a Society for the Improvement of Medical and Chirurgical Knowledge. 3: 1–6.