Jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots

The jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), are mainly known through the evidence of inventories held by the National Records of Scotland.[1] She was bought jewels during her childhood in France, adding to those she inherited. She gave gifts of jewels to her friends and to reward diplomats. When she abdicated and went to England many of the jewels she left behind in Scotland were sold or pledged for loans, first by her enemies and later by her allies. Mary continued to buy new jewels, some from France, and use them to reward her supporters. In Scotland her remaining jewels were worn by her son James VI and his favourites.

French fashion and the Scottish queen

Mary, Queen of Scots, inherited personal jewels belonging to her father, James V. For a time, the Earl of Arran was ruler of Scotland as regent. In 1556, after her mother Mary of Guise had become regent, Arran returned a large consignment of royal jewels to the young queen in France.[2] Among these jewels was a pendant or hat badge made in Edinburgh by John Mosman from Scottish gold, featuring a mermaid set with diamonds and holding a mirror and a ruby comb.[3] Mary mentioned in an undated letter to her mother that a member of the entourage of James Hamilton, 3rd Earl of Arran (then serving in the Scottish Guards in France) had told her that his father intended to send her some jewels, "quelques bagues".[4]

Mary had jewels repaired and refashioned by Parisian jewellers including Robert Mangot, who made paternoster beads or components, and Mathurin Lussault, who also provided gloves, pins, combs and brushes.[5] Lussault himself was a patron of the sculptor Ponce Jacquiot, who designed a fireplace for the goldsmith.[6] Her clothes were embroidered with jewels, a white satin skirt front and sleeves featured 120 diamonds and rubies, and coifs for her hair had gold buttons or rubies, sewn by her tailor Nicolas du Moncel in 1551.[7] In 1551, while she was in France, Mary of Guise considered buying necklaces from a Paris merchant called Ronnet (possibly for her daughter), and he supplied a valuation made by a Parisian jeweller and lapidary Allart Plombier or Plommyer, who sold jewels to the French royal family.[8]

In 1554 the queen's governess Françoise d'Estainville, Dame de Paroy, wrote to Mary of Guise asking permission to buy two diamonds to lengthen one of Mary's "touret" headbands, incorporating rubies and pearls the queen already owned, set in gold entredeux or chatons. She also wanted to buy a gown of cloth-of-gold for the queen to wear at the wedding of Nicolas, Count of Vaudémont (1524–1577), and Princess Joanna of Savoy-Nemours (1532–1568) at Fontainebleau. This new costume was intended to emulate the fashion adopted by the French princesses Elisabeth and Claude.[9]

The French court patronised an artist Jean Court dit Vigier who worked in enamels on metal, and he decorated and signed a cup or tazza with scenes of the Triumph of Diana and the Feast of the Gods, with the coat of arms of Scotland on the foot. The arms are surmounted by the Dauphin's crown and the piece has been called the queen's "betrothal cup", as it was conjectured it had been made for the occasion. The tazza is now in the collection of the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris.[10][11] It is not clear if the painter Jean de Court who received a pension from Mary and was listed as a 'valet' and painter in her household expenses was the same artist as the enameller.[12]

Jewels for wedding in Paris

Mary's mother, Mary of Guise, asked her to buy a chiming watch for her, from a maker who worked for Henry II.[13] Mary was betrothed to the French prince Francis, and was given jewels to wear which were regarded as the property of the French crown. Her jewelled appearance at their wedding in 1558 included a necklace with a pendant of "incalculable value", described as "a son col pendoit une bague d'une valeur inestimable.[14][15] Mary wrote that Henry II of France, Catherine, and her uncles had each given her a brodure de piarrerie, a border (perhaps for a French hood) set with precious stones.[16]

On the day of her wedding, suspended at her forehead from her crown, was the famous ruby called the "Egg of Naples".[18] Mary's mother-in-law, Catherine de' Medici, gave her the necklace and pendant which she had commissioned from goldsmiths in Lyon and Paris.[19] By the time of Mary's marriage, Mathurin Lussault was known as Mary's goldsmith. Other goldsmiths who worked for the wedding ensemble were; Jean Joly, Jean Doublet (the Dauphin's goldsmith), and Nicolas Vara, a gilder and engraver. Denis Gilbert trawled the shops of Paris for rings and stones, and a lapidary called Badouet supplied 58 emerald buttons. Two merchants from Lyon, Pierre Vast and Michel Fauré, supplied a faceted diamond set in a shield for the necklace that Catherine de' Medici gave Mary on her wedding day. The diamond cost 380 livres. Claude Héry supplied a cabochon diamond, costing 292 livres.[20] The pendant may have been the jewel later known as the Great H of Scotland.[21][22]

On 6 July 1559, Mary, as Reine dauphine, ordered counterfeit precious stones for masque costumes from a painter Éloi Lemannyer, for the weddings of Elisabeth of Valois and Margaret of Valois. Lemmanyer, an usher of the Dauphin's chamber, provided 1,262 imitation rubies, diamonds, and emeralds.[23] Henry II of France was injured at a tournament and died on 10 July. Mary asked the Duchess of Valentinois to make an inventory of the French king's cabinet and all his jewels.[24][25][26]

In the 1570s, Mary sent her godchild, a daughter of the French ambassador Michel de Castelnau, a jewel which had been a present in her childhood from Henry II as a pledge of her affection to the girl and her family.[27]

Gems and cuts

The inventories of Mary's jewels mention the cut of stones, referring in French to facets, points, triangles, and lozenge cuts. A diamond quarre was table-cut. A cabochon is a rounded form.[28][29] Mary had "ung saffiz taille a viij pampes", a sapphire cut in eight petals.[30] A small sapphire set a jour was prized as remedy for sore eyes, "ung petit saffiz a jour pour frotter les yeux". This sapphire was pierced to wear as a pendant and set with two gold leaves.[31] According to Hildegard of Bingen, a sapphire used as remedy for conjunctivitis was placed in the mouth and then a dab of saliva would be rubbed in the eye.[32] A jewel described as set a jour was of fine cut, colour, and quality, and did not need to be enhanced with foil in its setting.[33]

Heart-shaped stones were prized, and used in gift exchanges with Elizabeth I in the 1560s. Mary sent Elizabeth a "fair ring with a diamond made like a heart".[34] In 1577, Mary's secretary Claude Nau wrote to his brother in Paris for a heart-shaped or triangular diamond or emerald, a "beau et excellent diamant ou esmeraulde ... Je desire que ce soit ung coeur ou en triangle parfaict".[35] Mary sent James VI a ring in 1581, which he received in "good heart" and may have had heart-shaped diamond,[36] and in 1584, James VI used a heart-shaped cipher for his own name.[37] Diamond cutting in Europe has been associated with Louis de Berghem or de Berquen of Bruges, who is said to have cut a heart shaped diamond for Charles the Bold in 1475, although the story seems to be the invention of a 17th-century writer Robert de Berquen.[38][39]

Diamonds for jewellery in this period came from India, and many were cut and finished and traded at Antwerp.[40] Natural diamond crystals that did not require cutting were sold in Paris and Lisbon. Instead of diamonds, rock-crystal, "paste" or glass substitutes were used, which seem to have been acceptable in fine jewellery. Rubies came from Myanmar,[41] the balas ruby from Badakshan,[42] sapphires from Sri Lanka and Myanmar. Emeralds may have been sourced in the Salzburg Alps, and were brought from Colombia by the Spanish. Turquoise came from the Khorasan province of Iran and the Sinai. A costly amatiste orientalle listed among the jewels she left behind in France may have been a purple hued ruby or sapphire, a type of corundum sometimes called an "oriental amethyst", rather than a quartz amethyst.[43]

The inventories say little about the gold settings, except the predominant colours of any enamel decoration. Analysis of a small number of pieces from this period has shown the use of gold of around 21 carat purity.[44] In England, in 1576, Elizabeth I allowed the goldsmith John Mabbe to market his stock of jewellery made with gold under 22 ct fineness.[45]

Pearls

In 1562 Mary bought 264 large pearls from John Gilbert, an Edinburgh goldsmith.[46][47] Some of these were sent to Paris to be made into buttons, and the others were incorporated in jewellery made in Edinburgh.[48] Most pearls used in jewellery came from marine oysters and were imported. In the 16th-century marine pearls were collected on the coast of Venezuela and Cubagua by indigenous divers and enslaved Africans working for the Spanish Empire,[49] while Portugal exploited pearl fishing in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf.[50][51]

Scottish freshwater river pearls were also used and seem to have been usually smaller than marine pearl.[52] Scottish pearls were noted as an export to Flanders in 1435.[53] A daughter of Thomas Thomson, one of Mary's apothecaries, wore a headdress set with 73 Scottish pearls all of equal size.[54] In 1568, some of Mary's pearls were sold to Elizabeth I. The consignment included pearls as big as nutmegs, according to the diplomat Jacques Bochetel de la Forest. His French word for nutmeg was mistranslated as "black pearls".[55]

Mary returns to Scotland

After Francis II died in December 1560, Mary had to return many of the French crown jewels to Claude de Beaune, Dame du Gauguier, a lady-in-waiting and treasurer to Catherine de' Medici. The diamonds were described in detail and valued in the inventory.[56][57] The most important suite of hairpieces and necklaces featured the repeated crowned initial "F" for Francis. One large ruby was known as the "Egg of Naples", a large emerald was from Peru.[58][59] Catherine de' Medici gave Mary a receipt on 6 December 1560. An inventory in the National Records of Scotland shows Mary was allowed to keep some pieces, and she would later insist that much of her personal jewellery had been given to her in France. The inventory also records that Mary gave gifts of jewellery to Jane Dormer, Duchess of Feria, when she came to Amboise in April 1560.[60]

John Lesley, Bishop of Ross, provided a description of Mary's arrival in Scotland in September 1561. He said her luggage included furniture, hangings, apparel, many costly jewels and golden work, precious stones, "orient pearls most excellent of any kind that was in Europe", and many costly ornaments or "abilyeamentis" for her body, with much silver work of costly cupboards, cups, and plate.[61] Jewels for immediate or regular use were kept near her bedchamber. One of her French gentlewomen, Mademoiselle Rallay, was given lengths of linen, called "plette", to keep these jewels in.[62]

Mary had several sets of back and fore "garnishings" sometimes with a matching necklace. These were worn on the headband or coif over the forehead. In French they were called bordures.[63] One garnishing consisting of large pearls was listed as sewn on black velvet, but usually any fabric components were not mentioned.[64] Other items of clothing were densely embroidered with pearls, including a black velvet trimming for a gown, a "garniture de robe" banded with pearls in her English wardrobe in 1586.[65] She wore coifs, a kind of hair net, one threaded with beads of jet.[66] In 1578, left behind in Edinburgh Castle, were "sevin quaiffis of gold, silver, silk, and hair".[67] Her ear rings were described in Scots as "hingaris at luggis".[68]

Watches associated with Mary were made in France. One example is said to have been lost while riding between Hermitage Castle and Jedburgh and discovered in the early 19th-century. The emblems engraved on one of her watches were recorded and sketched in January 1575. The device of a tortoise and palm tree was used in 1565 on her silver "ryal" coins and some of the other emblems were embroidered by Mary and Bess of Hardwick on the Oxburgh Hangings.[69]

Rings for Elizabeth and Mary

Jewels were exchanged as gifts between monarchs.[70] Monarchs exchanged their portraits, and gifts of jewels were sometimes made in lieu of pictures. These gifts had differing nuances and significances. Queen Elizabeth I of England proposed sending her portrait to Mary in Scotland in January 1562, but her painter was unwell.[71]

Mary, Queen of Scots, told the English ambassador Thomas Randolph that she would send Elizabeth a ring with a diamond made like a heart by the envoy who brought the portrait, or with René II de Lorraine, Marquis d'Elbeuf who intended to visit the English court.[72] After the portrait failed to materialise, in June 1562 she told Randolph she would send the ring with some verses she had written herself in French.[73] Mary hoped to meet Elizabeth, and they would be "good sisters together". She put Elizabeth's letter near her heart, and told Randolph that the French diplomat Philibert du Croc would carry the ring and her letter to Elizabeth.[74]

Meanwhile, in August 1562, Mary sent Robert Dudley, later the Earl of Leicester, a "token" to wear, as remembrance of their "reciproque gude mynd". The jewel was carried to England by her French administrator Monsieur Pinguillon.[75] In different circumstances, Mary considered sending another token to the Earl of Leicester in May 1578.[76]

A diamond talks

George Buchanan wrote two Latin epigrams concerning Mary's gifts of diamond rings to Elizabeth, one titled Loquitur adamas in cordis effigiem sculptus, quem Maria Elizabethae Anglae misit, said to be a translation of Mary's original. A French translation is titled Un Dyamant parle, a diamond talks.[77][78] The English courtier and poet Sir Thomas Chaloner also translated the verse.[79] The gift to Elizabeth was widely reported, and the English bishop John Jewel sent copies of the verses to his friends. He was sceptical of Mary's diplomatic overtures and plans for a meeting of the two queens.[80]

It was said that King James or Charles I gave this ring with a heart-shaped diamond to Sir Thomas Warner which passed to his descendants including the surgeon Joseph Warner. The Warner ring has a rose pear-shaped diamond in a black-enamelled setting. The ring was also said to be one which Elizabeth gave to the Earl of Essex and he returned to her from the Tower of London. In various 19th-century accounts of the "Essex" and Warner rings, Mary's gift and the verses are associated incorrectly with her marriage to Darnley in 1565.[81]

Two jewels I have

Elizabeth sent Mary a diamond ring in December 1563, which she "marvellously esteemed".[82] Elizabeth, at this time, was trying to assert her power over Mary's marriage plans.[83] The ambassador Thomas Randolph delivered the ring to Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll, for Mary, because the Mary was staying in bed at Holyrood Palace after exhausting herself dancing at twenty-first birthday celebrations.[84] Still in bed, she held an audience for Randolph and showed him Elizabeth's diamond ring on her finger, which the company admired with compliments to the giver, and then Mary displayed the ring from her marriage to Francis II, saying "two jewels I have that must die with me, and willingly shall never out of my sight".[85]

Later, at supper after a wedding, Randolph heard Mary toast Elizabeth as "De Bon Coeur", meaning of good heart or "willingly".[86] The phrase was sometimes used on rings, and the idea of a heart was frequently evoked in ring exchange, whether or not the stone was heart shaped.[87] In January 1564, Mary held masques, with a costume theme of white and black. Randolph noted that she wore no other jewels except the diamond ring, the gift which he had brought from Elizabeth, worn as a pendant.[88]

Mary's portrait and Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I obtained a miniature portrait of Mary, presumably as a gift. In 1564, she showed a picture of Mary to the Scottish envoy Sir James Melville with other miniature portraits in a desk in her bed chamber.[89][90] Elizabeth gave Melville a diamond as a token for Mary.[91] In April 1566, Elizabeth I wore a miniature portrait of Mary on a gold chain at her waist or girdle. She made a point of showing the image to the Spanish ambassador Diego Guzmán de Silva, saying she was sorry to hear of Mary's troubles and the murder of David Rizzio.[92]

Gifts and jewels at the Scottish court

In October 1564 Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, arrived at the Scottish court, and gave Mary a "marvellous fair and rich" jewel, a clock and dial, and a looking glass set with precious stones in the "4 metals". He gave diamond rings to several courtiers and presents to the queen's four Maries.[93] The English ambassador Thomas Randolph observed Mary playing dice with Lennox, wearing a mask after dancing, and losing a "pretty jewel of crystal well set in gold" to the earl.[94]

In July 1565 Mary paid a French goldsmith, Ginone Loysclener, £76 Scots. This was probably for gifts at her wedding to Lord Darnley.[95] Mary's household list of 1567 includes a French goldsmith called Pierre Richevilain, but it is unclear if he ever worked in Scotland.[96] Mary employed and patronised goldsmiths in Edinburgh and Paris. French purchases were made from her French incomes, for which few records survive. In 1562 Mary bought 64 large pearls from an Edinburgh goldsmith John Gilbert. Four were added to a gold "pair of hours", 27 were sent to Paris to be made into buttons, and the rest were incorporated in a chain to hang from her girdle with rubies and diamonds.[97] Elizabeth I also bought jewels in Paris, and a list of queries made by her ambassador Nicholas Throckmorton gives an insight into purchasing and material literacy.[98] John Gilbert was described as the queen's goldsmith.[99] By 1566, Michael Gilbert, a wealthy Edinburgh burgess, was the queen's master goldsmith, and he was exempted from any military service that would take him away from his royal duties.[100]

A gold locket with a chalcedony cameo portrait of Mary, heart-shaped with a ruby tail, was once thought to have been assembled in Edinburgh, perhaps during Mary's reign.[101] It includes an enamelled gold oval backplate that appears to have been made as part of another locket. The heart locket is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland,[102] and is now recognised as the work of a 19th-century goldsmith Alfred André. The cameo portrait itself seems to be from Mary's time.[103] Mary wrote to France for portrait jewels, possibly cameos or miniature portraits, to give to her supporters in 1575.[104]

Marriage, pregnancy, pomander beads, and the Queen's will

Mary married Lord Darnley at Holyrood Palace with three rings, including a rich diamond.[105] Soon after the marriage the couple faced a rebellion now known as the Chaseabout Raid. In need of money, it was said they tried to pawn some of her jewels in Edinburgh for 2,000 English marks, but no-one would lend this sum.[106]

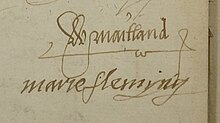

When Mary, Queen of Scots, was pregnant in 1566 she made an inventory of her jewels, leaving some as permanent legacies to the crown of Scotland, and others to her relations, courtiers, and ladies-in-waiting.[107] The inventory is regarded as a kind of will,[108] and was rediscovered at General Register House in Edinburgh in August 1854.[109] Mary Livingston and Margaret Carwood helped her and signed the documents.[110] The jewellery is sorted in categories, seven pieces were described as recent purchases.[111] The names of those who would have received jewels were used in studies of the members of the court and household of Mary by the historian Rosalind K. Marshall.[112]

Mary wanted the Earl of Bothwell to have a jewel for a hat with a mermaid set with diamonds and a ruby, which she kept close by her in her cabinet.[113] An "ensign" or hat badge in the form of a turtle "en tortue" with ten rubies had been a gift from David Rizzio and was bequeathed to his brother Joseph.[114] The queen's four year old nephew Francis Stewart, son of Lord John Stewart, would have had several sets of gold buttons and aiglets, and a slice of unicorn horn mounted on silver chain, used to test for poison.[115]

Marten furs and zibellini

If Mary had died in childbirth, one Scottish lady in waiting, Annabell Murray, Countess of Mar, and her daughter Mary Erskine would have received jewels including a belt of amethysts and pearls, a belt of chrysoliths with its pendant chain, bracelets with diamonds, rubies and pearls, pearl earrings, a zibellino with a gold marten's head, and yet another belt with a miniature portrait of Henri II of France.[116]

An Edinburgh goldsmith, John Mosman, had made a gold marten's head for her mother, Mary of Guise, in 1539. Mary had several, some described in French as "hermines" or as a "teste de marte" with matching gold feet to clip to the fur,[117] two heads were made of rock crystal.[118] Mary gave her mother's fur with a gold head and feet to Mademoiselle Rallay to mend, described as an item to wear around her neck, in December 1561.[119] In 1568, Mary left her sable and marten furs, and presumably the jewelled heads and feet, in Scotland with Mary Livingston and her husband John Sempill.[120] In June 1580, Mary wrote from Sheffield Castle to the Archbishop of Glasgow in Paris, asking him to send a "double marten" with gold head and feet, set with precious stones, to the value of 400 or 500 Écu. She wanted to wear it at the christening of Mary Talbot a daughter of the Countess of Shrewsbury.[121]

The accessory seems to have had allusions to pregnancy and fertility.[122][123][124] The Countess of Pembroke owned a diamond-studded sable head with a set of gold claws in 1562.[125] An engraving for the use of jewellery makers was published by Erasmus Hornick in 1562, which depicts a muzzled animal head with similarities to a zibellino belonging to Anna of Austria drawn by Hans Muelich in 1552, and another held by Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex, in one of her portraits at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge.[126][127]

Anne of Denmark may have inherited one of these, described in her inventory of 1606 as, "a sable head of gold with a collar or muzzle attached, garnished with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, with 4 feet".[128] The Earl of Leicester gave Queen Elizabeth a similar gold sable head and feet in 1585.[129] An example with a ruby tongue and feet set with turquoises was listed in the 1547 inventory of Henry VIII,[130] and was given to Lady Jane Grey,[131] and was among Elizabeth's remaining jewels in January 1604 valued at £19.[132] A gold head, with a marten skin, was imported with other jewels to London by an Italian merchant and milliner, Christopher Carcano, in 1544.[133]

Scented pomander beads and the rosary

Mary had two complete suites of head-dresses, necklaces and belts comprising openwork gold perfume beads to hold scented musk.[134] Mary bequeathed one set, with pearl settings in between the scented beads, to her half-sister Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll, the other to her sister-in-law Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray.[135] These items are not listed in later Scottish inventories and Mary may have given them away. The beads are known as pomander beads from the name of the scented compound or "sweet paste".[136] In 1576 a London goldsmith, John Mabbe, had 224 "pomanders of gold filled with pomander".[137]

Mary also had a pair of scented bracelets, described by the goldsmith, James Mosman, "ane pair of braslatis of gold of musk contenand everilk braslat four pieces and in every piece viij dyamonds and vij rubis and xj pearls in thaim both", which she bequeathed to the Countess of Mar.[138] In England, on 31 August 1568, Mary sent a chain of pomander beads strung on gold wire to Catherine, Lady Knollys, the wife of her keeper at Bolton Castle, Francis Knollys.[139] Knollys was at Seaton Delaval, and Mary sent the gift to him with a letter written in English and the Scots Language,[140] mentioning she had not yet met Lady Knollys. Lady Knollys was a courtier and close to Elizabeth.[141][142]

Rosary beads were known as "pairs of beads" and larger beads separating "decades" of beads were called "gawds" in Scotland and England.[143] Smaller spacing beads were called "jerbes" or "gerbes", a French term.[144] Mary gave Anne Percy, Countess of Northumberland, a "pair of beads of gold of perfume" which had been her gift from the Pope.[145] Mary gave other pieces with scented beads to her servants in England including a chain to Elizabeth Curle and bracelets to Mary, the daughter of Bastian Pagez. The Penicuik necklace (see below), in the National Museums of Scotland, comprises this type of pomander beads, and was Mary's gift to Gillis Mowbray.[146]

James V had owned perfumed beads, and in 1587, Jane Stewart, Countess of Argyll, Mary's half-sister, bequeathed her perfumed beads, described as "ane pair of muist beidis of gold", to Marie Stewart, Mistress of Gray.[147] New jewellery commissioned in Edinburgh in 1578 for Margaret Kennedy, Countess of Cassilis, included a locket or tablet filled with "fyne muist".[148]

The Royal Collection Trust has a larger silver gilt segmented pomander for scent traditionally identified as Mary's.[149] Pomander beads occur in the inventories of several royal women and aristocrats. A chain of small pomander beads with pearl "true-loves" was noted in the inventory of Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset.[150] Philip II of Spain gave Mary I of England a bracelet of 57 little pomander beads. Later Lady Anne Clifford owned this scented bracelet and wore it under her stomacher.[151][152] Lady Catherine Gordon, the widow of Perkin Warbeck, owned a "great pomander of gold" which she would have worn suspended by a chain from her belt or girdle.[153]

Accounts of Mary disrobing for her execution mention a chain of pomander beads, or her wearing a pomander necklace with an "Agnus Dei".[154] The inventories mention a rock crystal "Agnus Dei".[155] Contemporary accounts of the execution mention that Mary wore a "chaplet or beads, fastened to her girdle, with a gold cross" or "a pair of beads at her girdle with a golden cross".[156][157] Her two women, Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle, disrobed her of her "chayne of pomander beades and all other her apparell".[158]

Mary had written to the Bishop of Glasgow in November 1577 that she had been sent "chaplets" and an "Agnus Dei" from Rome. These may be the items mentioned in the narrative of her execution.[159] The gold rosary beads and a crucifix worn by Mary at her execution are said to have been bequeathed to Anne Dacre, Countess of Arundel, kept by the Howards of Corby Castle, and displayed at Arundel Castle.[160] The various manuscript accounts of Mary's death do not all agree on costume details, but it was noted in August 1586 that Mary usually wore a gold cross.[161] In Scotland, it was rumoured that Queen Elizabeth wore a crucifix hanging from a pair of beads, in the same manner, for three days in March 1565.[162]

Gifts at the baptism of Prince James

Mary safely gave birth to Prince James at Edinburgh Castle. According to Anthony Standen a diamond cross was fixed to James's swaddling clothes in the cradle.[163] His christening was held at Stirling Castle on 17 December 1566. Mary gave presents of her jewels as diplomatic gifts. The Earl of Bedford represented Queen Elizabeth at the baptism and was guest of honour at the banquet and masque.[164] She gave him a gold chain set with pearls, diamonds, and rubies.[165] According to James Melville of Halhill she also gave Christopher Hatton a chain of pearls and a diamond ring, a ring and a chain with her miniature picture to George Carey, and gold chains to five English gentlemen of "quality".[166] She received a necklace of pearl and rubies and earrings from the French ambassador, the Count de Brienne. In January 1567, Obertino Solaro, Sieur de Moretta, an ambassador of the Duke of Savoy, who was late for the baptism, gave Mary a fan with jewelled feathers. Bedford refused to go in the chapel at the baptism, and so Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll, went in his place, as godmother, and he gave her a ring with a ruby, from Elizabeth.[167]

Imagery of a mourning ring in the Casket Letters

It was said (in November 1573), that Mary gave James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell jewels worth 20 or 30,000 crowns.[168] The valet Nicolas Hubert alias French Paris said that Mary told him to give Bothwell a coffer of jewels and silverware.[169] Bothwell was said to have left jewels given to him by Mary worth 20,000 crowns in Edinburgh Castle when he fled to Orkney.[170]

After Mary was deposed, her enemies produced the Casket Letters, which she was said to have written to Bothwell and which demonstrated her involvement in the murder of Lord Darnley.[172] One of these letters, usually known as the third casket letter,[173] which was claimed to prove Mary's affection for Bothwell,[174] powerfully invokes the imagery of the gift of a memento mori ring in the context of Bothwell's absence and her regret.[175] She sends the ring with her servant, French Paris,[176] as a token not of mourning, but of her love, steadfastness, and their marriage. A French version of the letter describes the object as a jewel containing his name and memory joined with a lock of her hair, comme mes chevaulx en la bague.[177] The Scottish text of the letter was published by George Buchanan in his Detectioun, and, as printed by Robert Lekprevik at St Andrews in 1572, includes:

I have send yow ... the ornament of the heid [a skull, or a lock of her hair], quhilk is the chief gude of the uther memberis, ... the remnant cannot be bot subject to yow, and with consenting of the hart, ... I send unto yow a sepulture of hard stane, colourrit with black, sawin with teiris and banes. The stane I compare with my hart, ... your name and memorie that ar thairin inclosit, as is my hear[t] in this ring, never to cum forth quhill [till] deith grant unto yow to ane trophee of victorie of my banes, in signe that yow haif maid ane full conqueist of me, of myne hart, ... The ameling [enamel] that is about is blak, quhilk [which] signifyis the steidfastnes of hir that sendis the same. The teiris ar without number[178][179][180]

The phrases and metaphors in this letter, and the equation of the precious stone and Mary's heart, can be compared with the verses associated with Mary's previous gift of a ring to Elizabeth I. The word "sawin" means sown or strewn, the equivalent of French semée, the heraldic sprinkling of teardrops and bones that decorate a tomb.[181] When Mary was pregnant in 1566, she made a will bequeathing to Bothwell a diamond-set mermaid hat badge and a table diamond enamelled black, and to his countess Jean Gordon, a headdress, collar, and sleeves set with rubies, garnets, and pearls. Some writers have identified the diamond in the letter as the jewel in the bequest. Mary owned at least other two black-enamelled diamond rings.[182]

A literary parallel, noted by George Saintsbury, occurs in the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, in a tale (no. 26) where a woman gives her lover a gold ring decorated with tears, esmaillée de larmes noires,[183][184] as a sign of fidelity,[185] and such rings are found in French inventories, described as verges, the name for a ring given to a spouse.[186] It has been suggested that Jean Gordon or Anna Throndsen might have written such a letter to Bothwell.[187] John Guy concludes the original letter may have been from Mary to Darnley.[188]

The lion and the mouse

In 1567 Mary, Queen of Scots, was deposed and imprisoned in Lochleven Castle. Around the time she was made to abdicate, William Maitland of Lethington and Mary Fleming sent her a gold jewel or ring depicting the lion and mouse of Aesop's fable. This was a token alluding to the possibility of escape, and their continuing support for her, the mouse could free the lion by nibbling away the knots of the net. It had an Italian motto A chi basto l'animo, non mancano la forze, – to those with enough spirit, there is no shortage of strength. "All the place saw her wear it", and Marie Courcelles said it was a gift from Fleming.[189]

George Buchanan included the story in his Chamaeleon, a satirical account of Maitland's career, as "ane picture of the deliverance of the Lyoun by the Mouse".[190] Claude Nau described the jewel as a small oval gold locket with an enamelled picture, saying the queen's cipher was engraved inside the lid and it enclosed a paper with verses written in Italian.[191] This jewel seems to be listed in Mary's final inventory, in the keeping of Elizabeth Curle at Fotheringhay, as "A device of Esope in gold". Another list mentions a round jewel set with diamonds with an amethyst engraved with a lion and a motto.[192]

Regent Moray and the queen's jewels

When Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned at Lochleven Castle, in 1567, the Confederate Lords ordered that some of her silver plate, including a table ship called a nef, should be melted down and coined.[193][194]

Mary had asked an Edinburgh goldsmith James Mosman to convert a chain set with little diamonds into a hairband garnishing.[195] Mosman gave the finished item to Andrew Melville of Garvock, and he took it to the captive queen at Lochleven with some other pieces from her cabinet at Holyrood Palace.[196]

Her half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, returned from France. According to Nicholas Throckmorton, when he visited Mary at Lochleven in August, she asked him to look after her jewels for her son James and confirmed this in a letter.[197] Soon after, Moray became the ruler of Scotland and was known as Regent Moray. His secretary John Wood and Mary's wardrobe servant Servais de Condé made inventories of Mary's clothes and jewels.[198][199]

Her jewels and clothes in Edinburgh Castle were given up by the depute-governor Sir James Balfour in September 1567,[200] and were found to be of much greater value than first estimated.[201] Moray appointed his friend William Kirkcaldy of Grange as keeper of Edinburgh Castle and the jewel coffer. James Melville of Halhill wrote to the recently departed English diplomat Nicholas Throckmorton, that the Hamilton family, supporters of Mary, were disappointed that Edinburgh Castle and the jewels had been delivered to Moray and the Lords, an event that "cooled many of their stomachs".[202]

An English diplomat at Berwick, William Drury, observed that Regent Moray was "very bare of money, and of his own, little means to make money. The Queen's jewels shall go to gage, if not sold outright, if a chapman or lender upon reasonable interest may be gotten".[203] Regent Moray and the treasurer Robert Richardson raised loans with Mary's jewels as security and sold some pieces with precious stones to Edinburgh merchants.[204][205][206] In the Scots language, a jewel pledged for a loan was said to be "laid in wed". Robert Melville arranged with Valentine Browne, treasurer of Berwick, for loans secured on the jewels.[207][208]

Elizabeth buys Mary's pearls

John Wood and Nicoll Elphinstone marketed Mary's jewels in England.[209] Nicoll Elphinstone sold Mary's pearls to Queen Elizabeth, despite offers from Catherine de' Medici.[210][211] The chains of pearls were described by the French ambassador Jacques Bochetel de la Forest, some of the pearls were as big as nutmegs. There were no black pearls.[212][213] They are thought to be represented in Elizabeth's "Armada Portrait".[214] Elizabeth of Bohemia inherited these outsize pearls on the death of James VI and I in 1625.[215]

Jewels, merchants, loans, and widows

Other jewels sold by Regent Moray ended up in the hands of the widows of two merchants who dealt with him. Helen Leslie, the "Goodwife of Kinnaird", was the widow of James Barroun, who had loaned money to Moray. An emerald pledged to Barroun was sold in Paris. Helen Leslie married James Kirkcaldy, whose brother, Moray's friend William Kirkcaldy of Grange, unexpectedly declared for Mary in 1570.[216]

Helen, or Ellen, Achesoun, a daughter of the goldsmith John Achesoun,[217] was the widow of William Birnie, a merchant who had bought the lead from the roof of Elgin Cathedral in 1568 expecting a lucrative deal in scrap metal.[218] Achesoun and Birnie had lent Moray £700 Scots and taken as security some of Mary's "beltis and cousteris". The "couster", or in French a "cottouere" or "cotiere", was the gold chain that descended from a woman's belt with its terminal pendant. One of these was described in Scots as, "ane belt with ane cowter of gold and ceyphres (ciphers) and roissis quheit and reid inamelit (roses enamelled white and red), contenand knoppis and intermiddis (entredeux) with cleik (clasp) and pandent 44 besyd the said pandent."[219]

After Birnie died, Achesoun married Archibald Stewart, a future Provost of Edinburgh and friend of John Knox. A silver mounted "mazer" or cup made for the couple by James Gray, engraved with their initials, survives.[220][221] Despite their Protestant credentials, they later became financial backers of Mary's cause in Scotland by lending money to William Kirkcaldy, on the security of more of the queen's jewels.[222] In August 1579, James VI gave Robert Richardson, the son of the treasurer Robert Richardson, £5,000 Scots for the return of jewels pledged to his father in Regent Moray's time.[223]

Mary escapes from Lochleven castle and goes to England

After Mary escaped from Lochleven in May 1568, Robert Melville brought some jewels to her at Hamilton in the days before the Battle of Langside, including a ring and four or five target hat badges. Mary used these jewels as tokens in letters sent to her allies in Scotland, and sent the ring to Queen Elizabeth. There is some confusion about the ring or rings Mary sent to Elizabeth, either before or after Langside, from Scotland, or when she arrived in England.[224]

After her defeat at Langside, Mary made her way to England. Traditionally, she is said to have stayed her last night in Scotland at Dundrennan Abbey. An alternative tradition is that she stayed at a laird's house nearby, and gave her host a ring and a damask cloth.[225] The text of a letter to Elizabeth from Mary at Dundrennan returning Elizabeth's "token" of a ring after her defeat at Langside survives, apparently from a copy obtained by Michel de Castelnau.[226]

According to a contemporary chronicle, The Historie of James the Sext, Mary sent a message from Dundrennan before she left Scotland, and Elizabeth sent her a ring as a token of good faith.[227] John Maxwell, 4th Lord Herries of Terregles, wrote that he carried a diamond ring from Cockermouth to Elizabeth in London, one which Elizabeth had previously given Mary as a token of friendship.[228] Herries and Lord Fleming were watched by English guards in London in June 1568. The Spanish ambassador Diego Guzmán de Silva heard that Herries said to the Chancellor that Elizabeth ought to help Mary, according to a letter that Elizabeth recently had sent Mary with a token of a jewel.[229]

According to her secretary, Claude Nau, Mary sent Elizabeth ring with a diamond fait en roche with her servant John Beaton, which Elizabeth had given her after Mary had sent her the heart shaped diamond ring.[230] Robert Melville mentioned this ring in 1573, and that Mary gave four or five brooches or "targets" to her supporters at Hamilton.[231] A later letter of Mary also confirms the story of the ring, in November 1582, Mary wrote to Elizabeth, reminding her that when she had escaped from Lochleven and was about to do battle with her rebels, she sent Elizabeth a diamond ring.[232] The ring had been a gift from Elizabeth, with her promise to help.[233] Elizabeth gave her reply to her diplomat Robert Beale, saying her promise of help was offered before Darnley was killed.[234] Mary sent rings as gifts and tokens over the coming years, in January 1581 to James VI, probably intended as a New Year's Day gift.[235] James promised to take good care of the ring in her honour, and sent another in return.[236] She intended to send James a jewel, probably a ring, before her execution.[237]

A goldsmith at Bolton Castle

Mary's English household included a goldsmith in the first months. Possibly he mended fixings for her clothing, a role which Jacob Kroger supplied for Anne of Denmark. Francis Knollys worried that he might counterfeit seals from wax impressions for forged letters.[238] The goldsmith at Bolton Castle may have been Guyon Losselleur, named as kitchen servant in England,[239] who may have been the "Ginone Loysclener" mentioned as a goldsmith working for Mary in July 1565.[240]

Jewel sales are halted

The sale of Mary's jewels in England by Moray in 1568 were halted for diplomatic reasons after she arrived in England. Mary instructed her ally Lord Fleming to request that Charles IX prevent sales of her jewels in France.[241] Most of the remaining pieces which Mary had left behind in Scotland were kept in a coffer in Edinburgh Castle. In August 1568, the Parliament of Scotland exonerated Regent Moray from selling Mary's jewels, "with liberty to 'dispone' the rest as occasion shall serve".[242] Queen Elizabeth, following a request from Mary, wrote to ask him not to sell her jewels despite the powers granted by Parliament in August. Moray agreed and claimed he and his friends had not personally been "enriched worth the value of a groat of any of her goods to our private uses".[243]

An account written in French by or for Servais de Condé of costume and thread for textile crafts sent to Mary at Lochleven and in England from the wardrobe at Holyrood survives. It includes a girdle, a ceinture, of coral and pearl and the matching descending element then known as a cottoire, which was among the costume sent to Mary at Carlisle in July 1568: "plus, une sainture de corrall et de perlles avec le cattoyre de mesmes". This coral belt may have come into the possession of Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray,[244][245] another coral belt or girdle with gold spacer beads known as "gerbes" was in Edinburgh Castle in 1578.[246][247][248]

Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray, and the Great H of Scotland

After Regent Moray was assassinated in January 1570, Mary wrote from Tutbury and Sheffield Castle to his widow, Agnes Keith, asking for "our H", the "Great H of Scotland" and other pieces. Regent Moray and his secretary John Wood had taken them to England and brought them back unsold.[249] Mary's secretary wrote in Scots in March 1570:

we ar informit ye have tane in possession certane of oure jowalles sic as oure H of dyamant and ruby with a nombre of other dyamantis, rubiz, perles, and goldwark, wherof we have the memoir to laye to your charge. Quhilkis jowalles, incontinent eftir the sycht heirof ye sall delyver to oure richt trusty cousigns and counsalouris the earle of Huntley oure Lieutennent, and my Lord Setoun, quha will in sa doing give yow discharge of the same in oure nayme, and will move ws to have the more pitie of yow and your cheldren.

[modernised], we are informed you have taken possession of certain of our jewels such as our H of diamond and ruby with a number of other diamonds, rubies, pearls, and goldwork, whererof we have a memoir to lay to your charge. Which jewels, straightaway after the sight hereof you shall deliver to our right trusty cousins and counsellors, the Earl of Huntly, our Lieutenant, and my Lord Seton, who will in so doing give you discharge (a receipt and exoneration) in our name, and will move us to have the more pity of you and your children.[250]

Mary added a postscript in her own handwriting that her family and retainers would feel her "displesour".[251][252] Agnes Keith kept the jewels and sent no answer to Mary. Mary wrote for the jewels again in January 1571, again mentioning consequences for the children of the countess.[253] Moray's successor Regent Lennox wanted the jewels from her, writing in September 1570, while the Earl of Huntly wrote for them for Mary. Agnes Keith did not oblige.[254] The "Great H" or "Harry" may have been the priceless pendant which Mary had worn at her first wedding in 1558.[255]

Regent Lennox said in August 1570 he would not borrow money on the security of Mary's jewels, and promised to make an inventory of her things, her gowns and furnishings, which were safe in Edinburgh castle, apart from the tapestry hanging at Stirling Castle.[256] Mary wrote in November that Lennox "presumes to spoil us of certain jewels; yea, of the best we have". She heard that Lennox had imprisoned John Sempill in Blackness Castle for keeping some of her jewels and marten and sable furs, which she had left in Scotland with his wife Mary Livingston.[257]

Jewels and the Lang siege

During the "Lang Siege" of Edinburgh Castle, the last action of the Marian Civil War, the Captain of the castle, William Kirkcaldy of Grange gave jewels to supporters of Mary as pledges for loans. He used the money to pay his garrison. They also collected silver to mint coins in the castle.[258] The goldsmiths James Mosman and James Cockie valued the jewels as pledges for loans, and Mosman loaned his own money and accepted jewels as security.[259] Several documents concerning the jewels and loans survive from this time, retrieved from the jewel coffer in the castle, and are held by the National Records of Scotland, including a note about Mary's marriage ring, which was in the hands of Archibald Douglas.[260] On 1 March 1570, Grange wrote a memorandum about the jewels and the coffer. He noted that the keys to the castle jewel coffer were held by James Murray of Polmaise and Regent Moray had kept a key to one of the locks in his purse:

My awin hand writ is in the coffer for certen of the jowalls that wer tane out, quhairof James Murray hes the keys and quha sa ever got me lord purs quhen he deit hes the key of the hinging lok for he ware it aw' in his awin purs.

(modernised) My own hand writ is in the coffer for certain of the jewels that were taken out, whereof James Murray has the keys and whosoever got my Lord's purse when he died has the key of the hanging lock for he wore it always in his own purse.[261]

The siege caused great suffering in Edinburgh. The new ruler of Scotland Regent Morton, sent the Earl of Rothes to try to negotiate a surrender in the first days of April 1573.[262] Rothes discussed an exoneration for Grange for his "intromission" with Mary's jewels, which was understood to be for the "maintenance of her cause".[263]

Grange and the Castilians did not surrender. Instead, an English force was invited into Scotland, bringing artillery to bombard the castle. Morton made strenuous efforts to recover the jewels after the castle surrendered on 28 May 1573.[264] As English and Scottish soldiers entered the castle, James Mosman gave his share of the queen's jewels to Kirkcaldy, wrapped in an old cloth or "evill favoured clout", and he put them in a chest in his bedchamber.[265] The English commander at the siege, William Drury, recovered the jewel coffer from a vault and redeemed some jewels from lenders including Helen Leslie, Lady Newbattle, and Helen Achesoun. They came to his lodging at Leith where Kirkcaldy was held.[266] Henry Killigrew described the discovery of the jewel coffer, the Honours of Scotland, and the paperwork which identified those holding jewels as pledges:

in Grange's chamber sundry papers was found, and lately the crown, sword, and sceptre, and hidden in a wooden chest in a cave, where the inventory was of the jewels, which are many and rich, but the most part in gage [pawned], some with the lord of Ferniehirst, some with my Lady Hume, some with my Lady Lethington, and many with sundry other persons, who be all known.[267]

Grange had sent his cousin, Henry Echlin of Pittadro, to negotiate handing the Honours of Scotland (the crown, sceptre, and sword) and any other jewels that were not pawned to Regent Morton.[268] Thomas Randolph later recalled that William Drury and Archibald Douglas were involved in the sale of jewels and loans, earlier during the siege, when Drury and Randolph were ambassadors together.[269]

John Mowbray of Barnbougle presented a paper to Regent Morton, on behalf of 60 lairds, with offers to save the life of William Kirkcaldy of Grange. The offers included £20,000 worth of Mary's jewels remaining in her supporter's hands.[270] On 3 August 1573 William Kirkcaldy, his brother James, James Cockkie, and James Mosman were executed by hanging.[271]

Regent Morton and the jewels

Morton obtained the records of the loans and pledges made by Kirkcaldy, which survive today in the National Records of Scotland.[272] He later wrote of his pleasure at this find to the Countess of Lennox.[273] Kirkcaldy made a statement about the jewels for the benefit of William Drury. Amongst the papers from the castle, Kirkcaldy had written in the margins of an inventory gifts made, or to be made, to Margery Wentworth, Lady Thame, widow of John Williams, Master of the Jewels, and wife of William Drury. Kirkcaldy had blotted out some of these marginal notes, and now signed a statement that Lady Thame had refused any gifts of Mary's jewels from him back in April 1572 when she was staying at Restalrig.[274]

Mary Fleming, who had helped make this inventory of the jewels with her husband William Maitland and Lady Seton, was ordered to return a chain or necklace of rubies and diamonds.[275][276] Agnes Gray, Lady Home, surrendered a jewel with fifteen diamonds set in gold with white enamel and a pearl "carcat" necklace which together had been her security for a loan of £600 Scots.[277] The lawyer Robert Scott returned a "carcan" or garnishing, circled about with pearls, rubies and diamonds.[278] Two Fife lairds, Andrew Balfour of Montquhanie and Patrick Learmonth of Dairsie, who had made loans to Grange and charged interest, were ordered to surrender the jewels pledged to them.[279]

William Sinclair of Roslin had sold his pledge of 200 gold royal buttons weighing 31 ounces to the lawyer, Thomas McCalzean for 500 merks. McCalzean surrendered the buttons to the Privy Council and Morton on 6 July.[280] On 28 July 1573 the triumphant Regent sent Mary's gold buttons and pearl-set "horns", recovered from the Duke of Chatelherault, to Annabell Murray at Stirling Castle to be sewn on the king's clothes.[281]

On 3 August Morton sent a copy of Kirkcaldy's inventory to the Countess of Lennox, in the hope that she could get all the jewels still in William Drury's hands and now in Berwick sent to him.[282][283] On 7 August, on behalf of the Earl of Huntly, Alexander Drummond of Midhope brought Morton a garnishing for the queen's headband comprising seven diamonds (one large and cut square), six rubies, and twelve pearls set in gold. Huntly had raised a loan for this piece with Alexander Bruce of Airth.[284]

Morton wrote to Countess of Lennox again later in August, asking for a progress report. Ninian Cockburn, the bearer of his letter, had delivered some jewels from Archibald Douglas to Valentine Browne, treasurer of Berwick.[285] The French ambassador in London, Bertrand de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon summarised Morton's actions in September, saying that he reclaimed the jewels from those in Scotland that had them as pledges with threats or menaces, as they had lent money to rebels.[286] In October 1573 Morton sent money to Berwick to redeem one of the queen's garnishings, comprising a pair of headbands and a necklace of "roses of gold" set with diamonds.[287] Robert Melville was interrogated about the jewels in October.[288]

Mary was unhappy at the prospect of her jewels in Morton's hands and in the hands of merchants of goldsmiths, and wrote to the French ambassador in London, Bertrand de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon, about her concerns in November 1573. She wanted a fresh inventory and hoped Elizabeth I would intervene on her behalf. Mary wrote to Mothe-Fénelon that she hoped the jewels would be looked after in Scotland until her son James came of age.[289]

Gilbert Edward, the page of Valentine Browne, the treasurer of Berwick, ran away from his master and stole several jewels, including a jewelled mermaid.[290] Browne's mermaid was described in similar terms to an "ensign" Mary had inherited from her father, James V which he wore on a bonnet.[291][292] Mermaid jewels continued to be sewed on men's hats, in 1584 pirates stole a hat belonging to a David MacGill with a gold mermaid set with two rubies and a diamond, and three pendant pearls. The diamond typically formed the mermaid's mirror, with a ruby for her comb.[293]

Morton had a prolonged negotiation with Moray's widow, Annas or Agnes Keith, now Countess of Argyll, for the return of the diamond and cabochon ruby pendant called the "Great H of Scotland" and other pieces.[294] Unsurprisingly, Mary wrote again to the countess asking her to return the jewels to her instead. Agnes Keith claimed the jewels were security for her late husband's unpaid expenses as Regent, but she gave them to Morton in March 1575. A paper noting the return of the "Great H" to the crown by Agnes Keith, now the "Lady Ergile", and the recovery of other jewels survives in the National Archives of Scotland.[295] Around this time, Agnes Keith had to pawn her own jewels for money, raising 600 merks for her diamond-set "principal tablet" from a kinsman James Keith.[296]

In July 1575, there was a rumour that some of Mary's jewels had been exported from England at Gravesend, despite a prohibition.[297] Morton resigned the regency in March 1579, and his half-brother, George Douglas of Parkhead, made an inventory of royal jewels, her costume and her dolls, furnishings, and library.[298] The taking of this inventory was described in the chronicle attributed to David Moysie.[299]

Mary in England

When Mary was recently arrived in England, at Bolton Castle in July 1568, she asked a dependant of the border warden Lord Scrope called Garth Ritchie to ask Lord Sempill's son, John Sempill of Beltrees, the husband of Mary Livingston, to send her the jewels in their keeping. Garth Ritchie managed to bring some of the queen's clothes and a cloth of estate from Lochleven Castle, but Regent Moray would not give Sempill permission to send any jewels.[300] Regent Lennox would later ask John Sempill to return jewels and furs belonging to Mary to him, including sable and marten furs or zibellini. Mary declared that the jewels Sempill had were gifts from the King of France and did not pertain to Scotland.[301]

At Coventry in 1569, Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk gave Lord Boyd a diamond to deliver to Mary as a token of his affection and fidelity. Mary wrote to the Earl of Norfolk in December 1569, that she "would keep the diamond unseen about her neck till I give it again to the owner of it and me both".[302]

Mary had some jewelry and precious household goods with her in England. Inventories were made at Chartley in 1586 of pieces in the care of Jean Kennedy,[303] and at Fotheringhay in February 1587.[304] She usually wore a cross of gold and pearl earrings. Another gold cross was engraved with the Mysteries of the Passion.[305] She kept in her cabinet a gold chain with a miniature portrait of Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici. The chain had 44 pieces made as royal ciphers or initials, enamelled blue and red. The portrait was in a gold case called a "livret", an enamelled little gold book. The piece was probably worn as a belt or girdle.[306]

A mirror for her girdle

Mary wore a girdle around her waist with a descending chain and pendant, called in French a ceinture and cottoire. Some Scots language notes of some her jewels calls these items "beltis and cousturis", and a "belt and cowter with ane pandent of gold".[307] In January 1575, she wrote to James Beaton, Archbishop of Glasgow, in Paris for a pendant jewel, which she called "ung beau miroier d'or" – a fine gold mirror. She wanted it decorated with her cipher or initials and Elizabeth's combined, a motif designed by her uncle, the Cardinal of Lorraine.[308] Mary's inventory of 1586, includes a similar piece with her own portrait, to wear suspended from the girdle, "venant au dessoubs de la ceinture".[309] A list of other items taken from Mary Queen of Scots in 1586 includes a looking glass decorated with miniature portraits of Mary and Elizabeth (probably the girdle jewel with the combined cipher). There was also a gold pincase, an etui, to wear on a girdle.[310] In the same January 1575 letter, Mary also asked the Archbishop for four copies of her portrait set in gold, to distribute amongst her allies. They should be sent in secret. These were possibly cameo portraits, carved in hard stone, or miniature paintings.[311]

New Year's Day gifts

Mary continued to give New Year's Day gifts of gold jewellery, and in 1580 asked her ally James Beaton, Archbishop of Glasgow, to help buy and pay for these.[312][313] In October 1581, Mary planned with the Archbishop to make a declaration that her jewels (wherever they were now held) should be annexed and joined as to the crown jewels of Scotland. She noted that most of her jewels had been acquired during her time in France. This was drafted as part of a treaty known as the "Association", which was intended to restore Mary as joint ruler of Scotland with her son, James VI.[314]

Medical materials

A longer list of the queen's jewels was made at Chartley in 1586, and after her execution.[315] There were two porcelain spoons, one silver, one gold, a bezoar stone set in silver, and a slice of unicorn horn set in gold with a gold chain. There was a charm stone against poison, as big as a pigeon's egg, with a gold cover, and another stone to guard against melancholy. There were boxes of costly terra sigillata (an andidote to poison), powdered mummy, coral, and pearls. Some of these items were in the keeping of her physician Dominique Bourgoing.[316]

Pyramus and Thisbe

The Chartley inventory includes a jewel given to Mary by Elizabeth I,[317] depicting the story of Pyramus and Thisbe with the mulberry trees where the legendary couple met. The piece was described in French;

Un roc arbrisseaux d'or, enrichis de pierreries, répresentant l'histoire de Pyramys

A rock with golden shrubs, enriched with stones, representing the story of Pyramus.[318]

Described again in 1587 as a jewel in the form of rock, set with diamonds and rubies, in the keeping of Jane Kennedy, it was said to have been a gift from Elizabeth I eleven years before, brought to Mary by Robert Beale.[319] Beale had visited Mary's keeper, the Earl of Shrewsbury, in September 1575, and related Elizabeth's pleasure at receiving a gift from Mary, probably an embroidered skirt.[320]

Henry VIII gave a comparable jewel to Princess Mary in July 1546, described as a "broche of t'history of Piramys and Tysbye with a fayr table diamond in it". The brooch was also set with four rubies. Mary I gave it to her sister, the Lady Elizabeth, on 21 September 1553.[321] A jewel depicting Pyramus and Thisbe belonging to Claude of Valois, described in 1593, was made in the "German manner" and had a large round Scottish pearl as a pendant.[322] The Walters Art Museum has an oval renaissance locket with enamelled figures of Thisbe and Pyramus by a fountain, set on leaves of agate.[323]

Mary had been contrasted with Thisbe by her enemies. A ballad printed and circulated in Edinburgh in 1567 after the death of Darnley compared her alleged lack of grief to Thisbe's, "Hir lauchter lycht be lyke to trim Thysbie, Quhen Pyramus sho fand deid at the well".[324]

Jewels and portraits with political messages

Mary wrote from Sheffield Castle in 1574 and 1575 to her ally, the Archbishop of Glasgow, in Paris asking him to commission jewellery for her. She wanted gold lockets with her portrait to send to her friends in Scotland. Mary wanted bracelets or a pendant,[325][326] She wrote about a device, to be realised in gold and enamel, again in October 1578, to a token carried to her son.[327]

These requests to The Archbishop of Glasgow may be associated with the rosary beads and cross with an image of Susanna and the Elders inscribed Angustiae Undique (Beset on all sides) worn at her waist, as depicted in her so-called Sheffield Portraits.[328][329] The Archbishop also sent Mary a watch in January 1576, and she wrote to thank him for its jolie devises.[330] Although the watch does not survive, the devices or emblems were copied down. Six of the emblems also appear on the Oxburgh Hangings or were listed amongst her embroideries.[331]

The portraits she requested, "peinctures", intended to be distributed as keepsakes for her supporters,[332] may have been her profile cut in cameo. Several examples exist, and one is said to have been Mary's gift to Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk.[333][334][335] She also asked for a gold belt and necklace as a present for the daughter of her chancellor, Gilles du Verger.[336][337]

At this time, lockets with miniature portraits were generally known as "tablets" in England and Scotland. James VI and I wrote a poem addressed to his mistress Anne Murray, describing a gold tablet, its enamel decoration, and the absence of its painted portrait.[338]

The Duke of Norfolk, who entertained the idea of marrying the Scottish queen, had a gold tablet with her picture in 1570, and he sent her two diamond rings. An intercepted letter from Mary's supporters at Angers around this time mentioned a painter making pictures for Mary.[339] Mary sat for her portrait at Sheffield in August 1577, intending to send it to the Archbishop of Glasgow.[340][341] In the same month, her secretary Claude Nau wrote twice to his brother in Paris, Jean Champhuon, sieur du Ruisseau, asking him to buy some jewellery and send it to him in a small sealed box (une petite boite fermee et cachetee); a pair of bracelets made in the latest fashion and a diamond or emerald shaped like a heart or triangle.[342]

A sapphire ring in the possession of the Duke of Hamilton is thought to have been sent by Mary to Lord John Hamilton.[343] Mary sometimes sent rings with letters to her supporters. A ring reached Janet Scott at Ferniehirst Castle in October 1583 with Mary's letter. She received the letter from her son, and hoped to speak with the bearer of the letter who would have personal news from Mary.[344]

While she was at Chatsworth in September 1578, Mary wrote to the Archbishop of Glasgow again, sending a "device", a description of the concept and theme for a jewel she wanted to be made in gold and enamel as a gift for her son, James VI.[345][346]

Perhaps around the year 1584, Robert Beale brought Mary a jewel, fashioned like a rock with pearls and rubies. He was involved in negotiations about Mary's "Association". The jewel was presumably a gift from Elizabeth I.[347]

The lion shall be lord of all

In 1570 the Countess of Atholl, and her friends, known as the "Witches of Atholl", had commissioned a jewel which referred directly to the succession to the crown of England.[348][349] The jewel was discovered in October 1570 in a package sent to Mary, and described by the English ambassador Thomas Randolph,[350] and Alexander Hay. Hay wrote that its diameter was "na mair nor a mannis hand", just less than a hand's breadth, and it was "well dekkit with gold and anamelit". The shape of the piece was described, perhaps obscurely, as "maid in the form of a heirse of a harthorne".[351]

The jewel depicted a crowned queen in royal robes and the arms of Scotland, a thistle and a rose, with two lions. The motto was "Fall what may fall, the lion shall be lord of all".[352][353] Hay heard that Elizabeth I was disturbed by reports of the jewel the "familiar interpretation" of its message concerning the succession.[354] Years after, Mary wrote to the Countess of Atholl in March 1580, and mentioned "tokens", a gift of a book and her "picture" sent to Lord Seton and others.[355] Mary owned a jewel en rond in 1586 featuring a lion, apparently engraved on an amethyst.[356]

Lennox jewel

The surviving "Lennox Jewel" now in the Royal Collection and displayed at Holyrood Palace is a propaganda jewel of this type, thought to have been commissioned by Mary's mother-in-law Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox.[357] Its main inscriptions are "Quha hopis stil constantly vith patience sal obteain victorie in yair pretence", meaning that the patient and constant will be victorious in their claims,[358] and "My stait to yir I may compaeer for zou quha is of bontes rair", my state to these I may compare, for you whore are of rare goodness.[359]

The Lennox jewel has sometimes been attributed to prominent Edinburgh goldsmiths including Mungo Brady, Michael Gilbert, George Heriot and James Gray because the mottoes appear to be in Scots, although no evidence has yet been found that it, or the Countess of Atholl's jewel, were made in Scotland.[360] Recent researchers propose that Margaret Douglas commissioned the jewel from a London maker.[361]

The exact moment for the which the Lennox Jewel was made remains unclear. It has been suggested that it was made as a gift for Mary, Queen of Scots, before her marriage to Lord Darnley around 1564.[362] An alternative view relates the motifs and emblems to James VI and Regent Lennox, and the king of Scots' claim to the English throne. Perhaps, because Margaret Douglas did not use Scots spelling in her own writings, the piece was meant as a gift for James.[363]

Mary in chains

Some jewels were made to denigrate Mary's cause.[364] The Spanish ambassador in London, Antonio de Guarás, reported that the Earl of Leicester gave Queen Elizabeth as a New Year's Day gift in 1571 a jewel with a miniature painting showing her enthroned with Mary in chains at her feet, while Spain, France and Neptune bowed to her.[365][366][367]

Relics and the Earl of Northumberland

Mary owned two holy thorns, relics of the crown of thorns, a gift from her father-in-law, Henri II. The thorns had been bought in 1238 by Louis IX in Constantinople. Mary is said to have given the two thorns to Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland. One now belongs to Stonyhurst College, a gift from Thomas Weld. The thorn is housed in a gold reliquary decorated with spirals of pearls commissioned in 1590 by an English Catholic Jane Wiseman.[368][369] Jane Wiseman had a similar reliquary made for Mary's other thorn, lacking the pearls. This reliquary eventually found a home at Saint Michael's Church, Ghent.[370]

Mary sent other gifts to the Earl of Northumberland according to the confession of his servant Hameling in 1570, including an enamelled gold ring, a diamond ring, and for the Countess of Northumberland a pair of perfumed gold paternoster beads which the Pope had given to Mary and an enamelled silver necklace, the latter item delivered by Francis More. The Earl sent Mary a jewel that had been a gift to his wife from a Spanish courtier in the time of Mary I of England and a diamond ring from the Countess, and Mary swore she would always wear it.[371]

Crucifixes and rosaries

In 1566, an English spy, Christopher Rokeby visited Mary at Edinburgh Castle shortly before the birth of James VI. Mary's secretary, Claude Nau, wrote that "Ruxby" gave her an ivory locket depicting the crucifixion.[372] Mary's 1586 Chartley inventory mentions a gold cross that she habitually wore, and another engraved with the Mysteries of the Passion.[373]

A gold and enamelled crucifix is said to have been Mary's gift to John Feckenham, Abbot of Westminster, and contain a relic of the True Cross.[374] A much less elaborate silver crucifix found at Craigmillar Castle before 1815 is said to have hers. A sixteenth-century locket with a cameo vignette of the crucifixion and on the other side, the Assumption of Mary, is said have been her gift to Thomas Andrews, Sheriff of Northampton, shortly before her execution at Fotheringhay Castle.[375]

Abbot Feckenham's cross and the gold rosary beads with a crucifix said to be those worn at her execution are part of the collection at Arundel Castle,[376] and were stolen with other items on 21 May 2021.[377] Another rosary of garnet beads, with a silver gilt crucifix and medallion of the Virgin Mary, thought to have belonged to Mary, held by the Royal Collections Trust since 1980, is displayed at Holyroodhouse.[378]

According to Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, the gold cross at Fotheringhay contained a fragment of the True Cross with an image of Jesus. She passed it to one her ladies but the excutioner took it. The gentlewoman offered three times its value to recover it. Other accounts of the execution mention beads hanging at her girdle and an ivory crucifix in her hands.[379]

A full-length portrait of Mary now in the Scottish Portrait Gallery shows her wearing a crucifix, and a rosary of black beads and gold beads suspended from a cross-shaped jewel. The centre of this cross has a roundel depicting the story of Susanna and the elders, with the inscription angustiae undique – trouble is all around. Margaret Tudor and Mary I of England also owned jewellery depicting Susanna, a narrative championing innocence over conspiracy.[380]

A cross and rosary of gold filigree work, with 110 small beads and ten larger beads or "decades", was illustrated in William Bell Scott's 1851 Antiquarian Gleanings in the North of England, with a suggested provenance from Mary and the Melville family. The rosary then belonged to George Mennell of Picton House, Newcastle.[381]

James VI

James VI was able to wear the jewelled gold buttons that had belonged to his mother, and adapt the gold settings from her necklaces to adorn his bonnets. In October 1579 he became an adult ruler and left Stirling Castle. He ordered workmen to carry the coffer with his mother's jewels from Edinburgh Castle to Holyroodhouse.[382] In January 1581, Mary sent him a ring, and he sent another in return, entreating her in French "to receive from me in as good heart (dans sy bon cueur) as I took yours".[383] James sent a ring to Elizabeth I in July 1583.[384]

He gave several of his mother's jewels to his favourite Esmé Stewart in October 1581, including the "Great H" and a gold cross set with seven diamonds and two rubies. In September 1584 a German travel writer Lupold von Wedel saw James, who was staying at Ruthven Castle, wearing this cross on his hat ribbon in St John's Kirk in Perth.[385] In October the valet John Gibb returned the cross to the Master of Gray, the newly appointed Master of the Royal Wardrobe.[386] It was probably the same diamond and ruby cross that his grandmother, Mary of Guise, had pawned to John Home of Blackadder for £1000 when she was Regent of Scotland, and Mary, Queen of Scots, had redeemed.[387] Probably the same gold cross, with seven diamonds and two rubies, was pawned by Anne of Denmark to George Heriot in May 1609.[388] At this time, the king's hats were made by John Hepburn.[389]

The emerald and diamond tablet

On 24 April 1584 James VI obtained a loan of 6,000 merks from the burgh council Edinburgh, "for the supply of our present necessity". As security, his wardrobe servant John Gibb delivered a jewel called a tablet, set with a great emerald and a diamond to the Provost of Edinburgh, Alexander Clark of Balbirnie.[390] In October 1589 the next Provost John Arnot gave the jewel back to the king as a gift on his marriage.[391] It was delivered by Clark's son-in-law John Provand to William Fairlie, who commissioned the goldsmith David Gilbert to refashion and upgrade it, and the refashioned jewel, with pendant pearls, was presented in a velvet case decorated with the letter "A" to Anne of Denmark as the town's gift during her Entry to Edinburgh in May 1590.[392][393]

James Stewart, Earl of Arran

James Stewart, Earl of Arran, and Elizabeth Stewart, Countess of Arran, directed the Master of Gray to dress the king in his exiled mother's jewels. He had one of the queen's head garnishings of diamonds, pearls, and rubies broken up to embroider a cloak for the young king, during the visit of the English ambassador Edward Wotton in May 1585. Some of the gold settings were put on a bonnet string.[394] The English diplomat William Davison reported that the Countess of Arran had new keys made for the coffers containing Mary's jewels and clothes.[395] She was said to have tried on many of the old queen's garments to see if they fitted her, and chosen what she likes.[396][397] When Francis Walsingham came as a diplomat to Scotland in 1583, and James VI gave him a ring, Arran had substituted an inexpensive crystal for the diamond.[398]

According to the English ambassador William Knollys, the Countess of Arran was imprisoned at Blackness Castle in November 1585 for giving her husband jewels worth 20,000 crowns from Edinburgh Castle when he tried to leave the country.[399] Arran embarked on Robert Jameson's boat carrying royal jewellery including "Kingis Eitche", the Great H of Scotland. He was forced to give his treasure up to William Stewart of Caverston aboard ship in the coastal water known as the Fairlie Road.[400] Arran returned all the jewels in January 1586.[401]

Thomas Foulis and England

James VI gave some jewels to the goldsmith and financier Thomas Foulis to sell in England in the 1590s.[402] On 3 February 1603 King James gave James Sempill of Beltries, a son of Mary Livingston, a jewel which had belonged to Mary as a reward for his good service and faithful conduct in diplomatic negotiations in England. The jewel was a carcatt (a necklace chain) with a diamond in one piece and a ruby in another, with a tablet (a locket) set with a carbuncle of a diamond and ruby, set around with diamonds.[403]

In 1604 King James had the "Great H" dismantled and the large diamond was used in the new "Mirror of Great Britain" which James wore as a hat badge.[404]

The Eglinton parure

A necklace from the collection of the Earls of Eglinton is traditionally believed to have been Mary's gift to Mary Seton. The piece includes "S-shaped snakes in translucent dark-green enamel". It was divided into two in the 17th-century, one part is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland and the other, held by the Royal Collection, at Holyrood Palace. These may have been pieces of a longer chain or cotiere.[405][406][407]

The necklace and a painting once attributed to Hans Holbein were said to have come into the Eglinton family from the Setons in 1611, when Alexander Seton of Foulstruther, a son of Robert Seton, Earl of Winton and Margaret Montgomerie, became Earl of Eglinton.[408] He changed his surname to Montgomerie, and married Anne Livingstone, the childhood companion of Elizabeth of Bohemia and favourite of Anne of Denmark.[409]

Mary's biographer Agnes Strickland visited Eglinton Castle in 1847 and Theresa, Lady Eglinton lent her the necklace. Strickland's assistant Emily Norton made a drawing of it.[410] In 1894 George Montgomerie, 15th Earl of Eglinton rediscovered the necklace in the muniment room at Eglinton.[411] He sold it by auction, for the benefit of his sisters, according to his father's will. By this time the jewel had long been divided into at least two pieces, another chain with green serpents was at Duns Castle in the possession of the Hay family.[412] This section of the necklace came to the Hay family when Elizabeth Seton married William Hay of Drumelzier in 1694. The moiety from Eglinton was presented by Lilias Countess Bathurst to Queen Mary in 1935.[413]

Golf and the Seton necklace

Mary, Queen of Scots, and Lord Darnley played games like bowls and wagered high stakes, and in April 1565 when Mary Beaton won at Stirling Castle, Darnley gave her a ring and a brooch set with two agates worth fifty crowns.[414] A similar story is told of the Seton necklace, that the queen gave it to Mary Seton after she won a round of golf at Seton Palace. Mary certainly played golf at Seton, and in 1568 her accusers said she had played "pall-mall and golf" as usual at Seton in the days after Darnley's death.[415]

Mary Seton's golf connection was publicised around the time of the auction in Golf Magazine (March 1894), followed up by Robert Seton's 1901 Golf Illustrated article, 'Archery and Golf in Queen Mary's Time'.[416]

The Penicuik jewels and Gillis Mowbray

The Penicuik jewels were heirlooms in the family of John Clerk of Penicuik. They consist of a necklace, locket and pendant. The necklace has 14 large filigree open-work "paternoster" beads which could be filled with perfumed musk.[417] The locket has tiny portraits of woman and a man, traditionally identified as Mary and James VI. The gold pendant set with pearls may have been worn with the locket. The Penicuik jewels are displayed at the National Museum of Scotland.[418]

These pieces are traditionally believed to have belonged to Gilles or Gillis Mowbray of Barnbougle,[419][420] who served Mary, Queen of Scots, in England and was briefly betrothed to her apothecary, Pierre Madard.[421] Gillis Mowbray made her own way to London in September 1585 and made a request to join Mary's household.[422] Her sister Barbara Mowbray was already in the queen's household at Tutbury Castle and betrothed to marry the queen's secretary Gilbert Curll, and they married on 24 October 1585. Gillis was sent to Derby, and arrived at Tutbury on 9 November.[423] According to a list made in 1589, Gillis Mowbray (but perhaps Barbara), and her sister Jean Mowbray received pensions from Spain paid in gold ducats.[424]

Mary is known to have bought cloths and jewels for her household women. In September 1583 she wrote from Worksop Manor to Bess Pierpont mentioning that she had prepared a new black gown for her and had ordered her a "garniture" from London.[425] Mary bequeathed Gillis Mowbray jewels, money, and clothes, including a pair of gold bracelets, a crystal jewel set in gold, and a red enamelled "oxe" of gold.[426] She kept Mary's virginals, a kind of harpsichord, and her cittern.[427] It is possible that the bracelets comprised filigree beads which were converted into the Penicuik jewels necklace,[428] although Mary's inventories do include a little "carcan" necklace with small gold beads for perfume and with little gold grains as entredeux.[429] In August 1577, Mary's French secretary Claude Nau wrote to his brother in Paris, Jean Champhuon, sieur du Ruisseau, asking him to buy a pair of bracelets made in the latest fashion worth about 25 or 30 crowns and a precious stone, and sent them to him closed-up in a small box under seal.[430]