Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür

| Emperor Wenzong of Yuan 元文宗 Jayaatu Khan 札牙篤汗 ᠵᠠᠶᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12th Khagan of the Mongol Empire (Nominal due to the empire's division) Emperor of China (8th Emperor of the Yuan dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portrait of Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temur (Emperor Wenzong) during the Yuan era. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Yuan dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 16 October 1328 – 26 February 1329[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 16 October 1328 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ragibagh Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Khutughtu Khan Kusala | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 8 September 1329 – 2 September 1332 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Khutughtu Khan Kusala | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Rinchinbal Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 February 1304 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2 September 1332 (aged 28) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Empress | Empress Budashiri of the Khongirad (m. 1324–1332) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House | Borjigin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Yuan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Külüg Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Zhenge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jayaatu Khan (Mongolian: Заяат хаан ᠵᠠᠶᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤ; Jayaγatu qaγan; Chinese: 札牙篤汗), born Tugh Temür (Mongolian: Төвтөмөр ᠲᠦᠪᠲᠡᠮᠦᠷ; Chinese: 圖帖睦爾), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Wenzong of Yuan (Chinese: 元文宗; 16 February 1304 – 2 September 1332), was an emperor of the Yuan dynasty of China. Apart from Emperor of China, he is regarded as the 12th Khagan of the Mongol Empire, although it was only nominal due to the division of the empire.

He first ruled from 16 October 1328 to 26 February 1329 before abdicating in favour of his brother Kusala (Emperor Mingzong), and again ruled from 8 September 1329 to 2 September 1332 after Kusala's death.

Thanks to his father's loyal partisans, Tugh Temür did restore the line of Khayishan (Emperor Wuzong) to the throne but persecuted his eldest brother Kusala's family, and later expressed remorse for what he had done to him. His name means "Blessed/lucky Khan".

Tugh Temür sponsored many cultural activities, wrote poetry, painted, and read Chinese classical texts.[2] Examples of his quite competent poetry and calligraphy have survived. He mandated and closely monitored the compilation called "The Imperial Dynasty's grand institutions for managing the world"; through this textual production, he proclaimed his reign as new beginning, which took stock of the administrative practices and rules of the past and looked forward to a fresh chapter in Yuan dynastic governance.[3] But his reign was brief, and his administration was in the hands of powerful ministers, such as El Temür of the Qipchaq and Bayan of the Merkid who had helped him to win the succession struggle in 1328.

Early life

He was the second son of Khayishan (Külüg Khan or Emperor Wuzong) and a Tangut woman, and a younger brother of Kuśala. When his father Khayishan suddenly died and his younger brother Ayurbarwada inherited the Yuan throne in 1311, he and his brother were removed from the central government by his grandmother Dagi and other Khunggirad faction members including Temüder since they were not mothered by Khunggirad khatuns. After Ayurbarwada's son Shidibala ascended the throne in 1320, Tugh Temür was banished to Hainan.[4] When Shidibala was assassinated and Yesün Temür took over as the new ruler, conditions improved for Tugh Temür. He was given the title of Prince of Huai (Chinese: 懷王) and relocated to Jiankang (modern-day Nanjing) and then to Jiangling.[5] By this time he already showed a wide range of scholarly and artistic interests and had surrounded himself with many distinguished Chinese literati and artists. As the persecuted sons of Khayishan Külüg Khan, Tugh Temür and Kusala still enjoyed a measure of sympathy among the Borjigin princes and, more importantly, the lingering loyalty of some of their father's followers who had survived various political purges.

Civil war

The death of Yesün Temür Khan in Shangdu in 1328 gave Khayishan's line an opportunity to surface. But it was mainly due to El Temür's political ingenuity, whose Qipchaq family reached its zenith under Khayishan. He activated a conspiracy in the capital Khanbaliq (Dadu, modern Beijing) to overthrow the court at Shangdu. He and his entourages enjoyed enormous geographical and economic advantages over the loyalists of Yesun Temur. Tugh Temür was recalled to Khanbaliq by El Temür since his more influential brother Kuśala stayed in far-away Central Asia. He was installed as the new ruler in Khanbaliq in September while Yesün Temür's son Ragibagh succeeded to the throne in Shangdu with the support from Yesün Temür's favourite retainer Dawlat Shah.

Ragibagh's forces broke through the Great Wall at several points, and penetrated as far as the outskirts of Khanbaliq. El Temür, however, was able to turn the tide quickly in his favour. The restorationists from Manchuria (Liaodong) and eastern Mongolia launched a surprise attack on the loyalists. Their army under the command of Bukha Temur and Orlug Temur, descendants of Genghis Khan's brothers, surrounded Shangdu on 14 November, at a time most of the loyalists were involved on the Great Wall front.[6] The loyalists in Shangdu surrendered on the very next day, and Dawlat Shah and most of the leading loyalists were taken prisoner and later executed. Ragibagh was reported to be missing.[2] With the surrender of Shangdu, the way to restoring Khayishan's imperial line was cleared, although the loyalists elsewhere continued the fighting until 1332.

Regicide and purge

At the same time, however, his elder brother Khutughtu Khan Kusala gathered support from princes and generals in Mongolia and Chagatai Khanate and entered Karakorum with the overwhelming military presence. Realizing disadvantages, Tugh Temür declared abdication and summoned his brother. Accompanied by the Chagatai ruler Eljigidey, Kusala in response enthroned himself on 27 February 1329 north of Karakorum.[7] El Temür brought the imperial seal to Kuśala in Mongolia and announced Dadu's intent to welcome him, and Tugh Temür was made heir apparent. According to an oral tradition, Kusala's retainers treated him discourteously when he came to the camp of Kusala, thus making him both fearful and angry.[8] But Kusala thanked El Temür and appointed him grand councillor of the right wing of the Secretariat with the title of Darqan taishi.[9] Kuśala had proceeded to appoint his own loyal followers to important posts in the Secretariat, the Bureau of Military Affairs, and the Censorate.

On his way to Dadu, on 26 August, Kuśala met with Tugh Temür in Ongghuchad near Shangdu. Only 4 days after a banquet with Tugh Temür, he suddenly died, or was supposedly killed with poison by El Temür who feared losing power to princes and officers of Chaghadayid Khanate and Mongolia who followed Kuśala. Tugh Temür was restored to the throne on 8 September 1329. His conspiracy and victory over the loyalists and the death of Kusala eliminated the power of the steppe candidates from Mongolia.

Tugh Temür's administration carried out a bloody purge against its enemies. Not only leading supporters of Yesün Temür's successor Raghibagh were executed and exiled, but their properties were confiscated. Tugh Temür denied posthumous names of Yesün Temür and Raghibagh, and destroyed the chamber in the imperial shrine which contained the tablet of Yesün Temür's father Gammala. El Temür purged pro-Kuśala officers and brought power to warlords.

Reign

Efforts to win recognition

Because Tugh Temür's accession was so transparently illegitimate, it was more important for his regime than for any previous reign to rely on liberal enfeoffments and generous awards to rally support from the nobility and officialdom. During his four-year reign, twenty-four princely titles were handed out, nine of which were of the first rank. Of these nine first-rank princes, seven were not even Kublai Khan's descendants. Not only were the imperial grants restored in 1329, but all the properties confiscated from the Shangdu loyalists also were given to princes and officials who had made contributions to the restoration; in all, 125 individual properties are estimated to have changed hands.

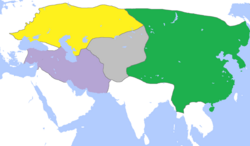

Action was also taken to win recognition from the other Mongol khanates to be accepted as their nominal suzerain. Tugh Temür sent three princes with lavish gifts to the Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate and the Ilkhanate.[10] And he also sent Muqali's descendant Naimantai to Eljigidey, who strongly supported Kusala, to give the royal seal and gifts in order to mollify his anger. However, Tugh Temür made regarding success, and saw favourable responses. Thus Tugh Temür was able to re-establish suzerainty over the Mongol world for himself and to maintain a close relationship with the three western khanates.[11]

Administration and court life

The four-year reign of Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür was dominated by El Temur and Bayan of the Merkid. As the persons who had been chiefly responsible for making the restoration possible, they acquired a measure of power and honour that had never before been attained by any official in the Yuan. They built their own power bases in the bureaucracy and the military, and their role overshadowed Tugh Temür. Tugh Temür honoured his father's former ministers and gave them honorific titles, and restored the honours of Sanpo and Toghto who had been persecuted by Ayurbarwada. The participants in the restoration were given most of the positions of importance in his administration. A few of the Muslims held posts in provinces, however, they did not have any position in the central government.

In the latter part of 1330 the Emperor went in person to perform the great sacrifice to the sky, which was done by deputy. This was followed by a general amnesty, and by the proclamation of his young son Aratnadara as heir apparent in January 1331. Tugh Temür's consort Budashiri, having a grudge against Babusha, the widow of Kusala, had her assassinated by a eunuch.[12] Then she sent Kusala's son Toghon Temür in exile to Korea to secure her son's succession; but Aratnadara died one month after his designation as heir.[13] This sudden death of his son completely upset Tugh Temür's plan for succession. Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür caused his another son, Gunadara (Kulatana), to live with El Temur and recognize him as his father, and changed his name to El Tegus.[14]

Because a budget deficit of the government drastically increased, and reached 2.3 million ding of paper currency in 1330 alone, Tugh Temür's court attempted to curtail its spending on such items as imperial grants, Buddhist sacrifices, and palace expenses. With those measures, they could keep the budget deficit within manageable figure, and had sufficient grain reserves at its disposal.

Prince Tugel Rebellion

The added costs of the war against the loyalists and the suppression of the revolts by the ethnic minorities, and natural disasters heavily taxed resources of Tugh Temür's government. The war in Yunnan continued with doubtful success, but the Imperial general Aratnashiri having collected an army of 100,000 men, defeated the Lolos and other mountaineers, and killed two of their chiefs. He seems to have quelled the rebellion and pacified Yunnan and Sichuan. Lo yu, one of the rebel chiefs in Yunnan, had escaped to the mountains; he collected a body of his people, and, dividing them into sixty small parties, overran the country of Chunyuen, where they committed frightful devastation. A force marched against them and Tugh Temür's army stormed their chief stronghold. Three sons and two brothers of Prince Tugel were made prisoners, while a third brother drowned himself rather than fall into the hands of the imperial army. Tugel's partisans gave up their cause in March 1332.[15] This campaigns costed 630,000 ding of paper currency.[16] Tugh Temür, who preferred luxury life, hardly deigned to show any interest in this distant campaign. The conduct of the Emperor caused much discontent, and Yelu Timur, son of Ananda who attempted to take the throne in 1307, in conjunction with the heads of the Lama religion in China, formed a plot to displace him; but this was discovered, and they were duly punished.

Academy, arts and learning

Tugh Temür had a good knowledge of the Chinese language and history and was also a creditable poet, calligrapher, and painter. With his actual power greatly circumscribed by El Temür, Tugh Temür is known for his cultural contribution. Posing as a cultivated sovereign of the Yuan, Tugh Temür adopted many measures honouring Confucianism and promoting Chinese cultural values. In 1330, he awarded laudatory titles to several past Confucian sages and masters, and himself performed the suburban offerings (Chinese: 孝祖) to Heaven, and thus became the first Yuan emperor to perform in person this important traditional Chinese state observance.[17] To promote Confucian morality, the court each year honoured many men and women who were known for their filial piety and chastity.

To prevent the Chinese from following Mongolian and hence un-Confucian customs, the government decreed in 1330 that men who took their widowed stepmothers or sister-in-law as wives, in violation of their own community's customs, would be punished. In the meantime, to encourage the Mongols and the Muslims to follow the Chinese customs, the officials of these two ethnic groups were allowed in 1329 to observe the Chinese custom of three years of mourning for deceased parents. He supported Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism and also devoted himself in Buddhism. He supervised the construction of the Stupa of Master Zhaozhou in the Buddhist Bailin Temple.

His most concrete effort to patronize Chinese learning was his founding of the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature (Chinese: 奎章閣學士院), first established in the spring of 1329, and was designed to undertake "a number of tasks relating to the transmission of Confucian high culture to the Mongolian imperial establishment". These tasks included the elucidation of the Confucian classics and Chinese history to the emperor; the education of the scions of high-ranking notables and the younger members of the kesig; the collection, collation, and compilation of books; and the appraisal and classifications of the paintings and calligraphic works in the imperial collection. Of the 113 officials successively serving in the academy, there were many distinguished Chinese literati, and the best Mongolian and Muslim scholars of Chinese learning of the time. Concentrating so many talents in one governmental organ to perform various literary, artistic, and educational activities was unprecedented not only in the Yuan dynasty but also in Chinese history.

The academy was responsible for compiling and publishing a number of books. But its most important achievement was its compilation of a vast institutional compendium named Jingshi Dadian (Chinese: 經世大典, "Grand canon for governing the world"). The purpose of bringing together and systematizing all important Yuan official documents and laws in this work according to the pattern of Huiyao (Chinese: 會要, "Comprehensive essentials of institutions") of the Tang and Song dynasties was apparently to demonstrate that Yuan rule was as perfect as that of earlier Chinese dynasties. Started in May 1330, this ambitious project was completed in thirteen months. It later provided the basis for the various treatises of the Yuanshi (History of Yuan), which was compiled at the beginning of the Ming dynasty.

Later life

Due to the fact that the bureaucracy was dominated by El Temür, whose despotic rule clearly marked the decline of the empire, the actual impact of the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature on the government as a whole was limited. El Temür eventually seized control of the academy in early 1332, just six months before the death of Tugh Temür. The academy had come to an end after Tugh Temür's death. Although El Tegüs was still alive, on his deathbed Tugh Temür expressed remorse for what he had done to his elder brother, Kusala, and his intention to pass the throne to Toghon Temür. After Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür died on 2 September 1332, Kuśala's second son Rinchinbal was installed by El Temür only at the age of six because Toghon Temür was far away from the central government.

Family

- Parents:

- Wives and children:

See also

- List of emperors of the Yuan dynasty

- List of Mongol rulers

- List of rulers of China

- Chinese art

- War of the Two Capitals

- Yuan dynasty in Inner Asia

- Yuan dynasty poetry

References

- ^ Moule 1957, p. 104.

- ^ a b Frederick W. Mote-Imperial China 900–1800, p. 471.

- ^ On Cho Ng, Q. Edward Wang-Mirroring the past, p. 184.

- ^ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank-The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, p. 542.

- ^ Yuan shi, 35. p. 387.

- ^ Yuan shi, 32, p. 605.

- ^ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank-The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, p. 545.

- ^ Fujishima Tateki-Gen no Minso no Shogai, p. 22.

- ^ Sh.Tseyen-Oidov-Chinggis bogdoos Ligden Khutughtu hurtel (khaad), p. 108.

- ^ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett- Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368 p. 543.

- ^ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett- Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368 p. 550.

- ^ It is said that Budashiri accused her of installing his son Toghon Temür to the throne instead of the living khan's line

- ^ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank-The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, p. 557.

- ^ Yuan shi, 35, p. 790.

- ^ Yuan shi, 31, p. 701.

- ^ li-Yuan shih hsian chiang, vol.3, p. 527.

- ^ Henry H.Howorth-History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century: part 1, p. 309.

- The Cambridge History of China By Denis Twitchett, Herbert Franke, John K. Fairbank ISBN 0-521-24331-9, Cambridge University Press, 1994

- Mediaeval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources By E. Bretschneider, Routledge ISBN 0-415-24486-2, Routledge, 2001

- "The Chaghadaids and Islam: the conversion of Tarmashirin Khan (1331–34)". The Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1 October 2002. Biran

- Moule, Arthur C. (1957). The Rulers of China, 221 BC-AD 1949. London: Routledge. OCLC 223359908.