Propaganda in Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II

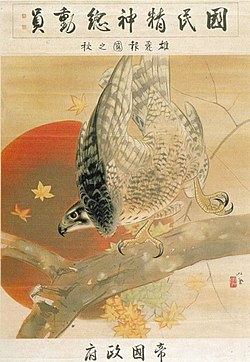

Japanese propaganda in the period just before and during World War II, was designed to assist the regime in governing during that time. Many of its elements were continuous with pre-war themes of Shōwa statism, including the principles of kokutai, hakkō ichiu, and bushido. New forms of propaganda were developed to persuade occupied countries of the benefits of the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, to undermine American troops' morale, to counteract claims of Japanese atrocities, and to present the war to the Japanese people as victorious. It started with the Second Sino-Japanese War, which merged into World War II. It used a large variety of media to send its messages.

Films

The Film Law of 1939 decreed a "healthy development of the industry" which abolished sexually frivolous films and social issues.[1] Instead, films were to elevate national consciousness, present the national and international situation appropriately, and otherwise aid the "public welfare."[2]

The use of propaganda in World War II was extensive and far reaching but possibly the most effective form used by the Japanese government was film.[3] Japanese films were produced for a far wider range of audiences than American films of the same period.[4] From the 1920s onward, Japanese film studios produced films legitimizing the colonial project that were set in its colonies of Taiwan, Korea, and on the Chinese mainland.[5] By 1945 propaganda film production under the Japanese had expanded throughout the majority of their empire including Manchuria, Shanghai, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia.[5]

In China, Japan's use of propaganda films was extensive. After Japan's invasion of China, movie houses were among the first establishments to be reopened.[3] Most of the materials being shown were war news reels, Japanese motion pictures, or propaganda shorts paired with traditional Chinese films.[3] Movies were also used in other conquered Asian countries usually with the theme of Japan as Asia's savior against the Western tyrants or spoke of the history of friendly relations between the countries with films such as, The Japan You Don't Know.[6][7]

China's rich history and exotic locations made it a favorite topic of Japanese film makers for over a decade before the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[5][6] Of particular note were a popular trio of "continental goodwill films" (大陸親善映画) set throughout the Chinese continent and starring Hasegawa Kazuo as the Japanese male romantic lead with Ri Kōran (Yoshiko Yamaguchi) as his Chinese love interest.[5] Among these films, Song of the White Orchid (1939, 白蘭の歌), China Nights (1940, 支那の夜), and Vow in the Desert (1940, 熱砂の誓い) mixed romantic melodrama with propaganda in order to represent a figurative and literal blending of the two cultures onscreen.[8]

‘National policy films’ or propaganda pictures used in World War II included combat films such as Mud and Soldiers (1939, 土と兵隊) and Five Scouts (1938, 五人の斥候兵), spy films such as The Spy isn't Dead (1942, 間諜未だ死せず) and They're After You (1942, あなたは狙われている) and lavish period pictures such as The Monkey King (1940, 孫悟空) and Genghis Khan (1943, 成吉斯汗).[5] In the early stages of the war with China, so-called "Humanistic war films" such as The Five Scouts attempted to depict the war without nationalism. But with Pearl Harbor, the Home Ministry demanded more patriotism and "national polity themes" – or war themes.[9] Japanese directors of war films set in China had to refrain from explicit anti-Chinese rhetoric. The risk of alienating the same cultures that the Japanese ostensibly were "liberating" from the yoke of Western colonial oppression was a powerful deterrent in addition to government pressure.[5] Even so, as the war in China worsened for Japan, action films such as The Tiger of Malay (1943, マライの虎) and espionage dramas like The Man From Chungking (1943, 重慶から来た男) more overtly criminalized Chinese as enemies of the Empire.[5] In contrast to its representations of China as antiquated and inflexible, Western nations were often portrayed as overindulgent and decadent.[10] Such negative stereotypes had to be adjusted when Japanese film makers were asked to collaborate with Nazi film crews on a number of Axis co-productions that followed the conclusion of the Tripartite Pact.[11]

As Westerners increasingly fought in the Pacific Theater, the Japanese directed their prejudices towards them too. In Fire on That Flag! (1944, あの旗を撃て!) the cowardice of the fleeing American military is juxtaposed with the moral supremacy of the imperial Japanese army during the occupation of the Philippines. Japan's first full-length animated feature film Momotarō: Divine Soldiers of the Sea (1945, 桃太郎海の神兵) similarly portrays the Americans and British in Singapore as morally decadent and physically weak "devils".[5] A sub-category of the costume picture is the samurai movie.[6] Themes used within these films include self-sacrifice and honor to the emperor.[10] Japanese films often did not shy away from the use of suffering, often portraying its troops as the underdog. This had the effect of making Japan look as though it was the victim inciting greater sympathy from its audience.[4] The propaganda pieces also often illustrated the Japanese people as pure and virtuous depicting them as superior both racially and morally.[10] The war is portrayed as continuous and is usually not adequately explained.[10]

Some other examples of propaganda films include Momotarō no Umiwashi and The Most Beautiful.

Magazines and newspapers

Magazines supported the war from its beginnings as the Second Sino-Japanese War with stories of heroism, tales of war widows, and advice on making do.[12]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, control tightened, aided by the patriotism of many reporters.[13] Magazines were told that the cause of the war was the enemy's egoistic desire to rule the world, and ordered, under the guise of requests, to promote anti-American and anti-British sentiment.[14] When Jun'ichirō Tanizaki began to serialize his novel Sasameyuki, a nostalgic account of pre-war family life, the editors of Chūōkōron were warned it did not contribute to the needed war spirit.[15] Despite Tanizaki's history of treating Westernization and modernization as corrupting, a "sentimental" tale of "bouregeoise family life" was not acceptable.[16] Fearful of losing supplies of paper, it cut off the serialization.[15] A year later Chūōkōron and Kaizō were forced to "voluntarily" dissolve after police beat confessions out of "Communist" staffers.[16]

Newspapers added columnists to whip up martial fervor.[17] Magazines were ordered to print militaristic slogans.[18] An article "Americanism as the Enemy" said that the Japanese should study American dynamism, stemming from its social structure, which was taken as praise despite the editor's having added "as the Enemy" to the title, and resulted in the withdrawal of the issue.[19]

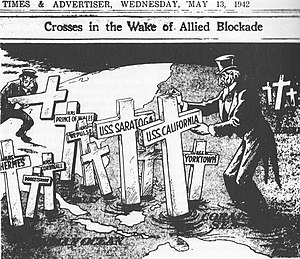

Cartoons

Cartoonists formed a patriotic association to promote fighting spirit, stir up hatred of the enemy, and encourage people to economize.[20] A notable example was the Norakuro manga, which began pre-war as humorous episodes of anthropomorphic dogs in the army, but eventually developed into propaganda tales of military exploits against the "pigs army" on the "continent" - a thinly-veiled reference to the Second Sino-Japanese War.

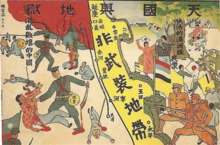

Cartoons were also used to create informational papers, to instruct occupied populations, and also soldiers about the countries they occupied.[5][21]

Kamishibai

A form of propaganda unique to Japan was war themed Kamishibai "paper plays": a street performer uses Emakimono "picture scrolls" to convey the story of the play. Audiences typically included children who would buy candy from the street performer providing his source of income. Unlike American propaganda that often focused on the enemy, Japanese wartime "National Policy" Kamishibai usually focused on themes of self-sacrifice for the nation, the heroism of martyrs, or instructional messages such as how to respond to an air-raid warning.[22]

Books

The Shinmin no Michi or Path of Subjects described what the Japanese should aspire to be, and depicted Western culture as corrupt.[23]

The booklet Read This and the War is Won, printed for distribution to the army, not only discussed tropical fighting conditions but also why the army fought.[23] Colonialism was presented as a tiny group of colonists living in luxury by placing burdens on Asians; because ties of blood connected them to the Japanese, and Asians had been weakened by colonialism, it was Japan's place to "make men of them again."[24]

Textbooks

The Ministry of Education, led by a general, sent out propagandistic textbooks.[25] Military oversight of education was intense, with officers arriving at any time to inspect classes and sometimes rebuke the instructor before the class.[26]

Similarly, textbooks were revised in occupied China to instruct Chinese children in heroic Japanese figures.[27]

Education

Even prior to the war, military education treated science as a way to teach that the Japanese were a morally superior race, and history as teaching pride in Japan, with Japan not being only the most splendid nation, but the only splendid one.[28]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, elementary schools were renamed "National Schools" and charged to produce "children of the Emperor" who would sacrifice themselves for the nation.[29] Children were marched to school where half their time was spent on indoctrination on loyalty to the emperor, and frugality, obedience, honesty, and diligence.[30] Teachers were instructed to teach "Japanese science" based on the "Imperial Way", which precluded evolution in view of their claims to divine descent.[31] Students were given more physical education and required to perform community service.[32] Compositions, drawings, calligraphy, and pageants were based on military themes.[33] Those who left school after completing six years were required to attend night school for Japanese history and ethics, military training for boys, and home economics for girls.[32]

As the war went on, teachers lay more emphasis on the children's destiny as warriors; when one child grew airsick on a swing, a teacher told him he would not be a good fighter pilot.[34] Pupils were shown caricatures of Americans and British to instruct them about their enemy.[34]

Girls graduating on Okinawa heard a speech by their principal on how they must work hard to avoid shaming the school before they were inducted into the Student Corps to act as nurses.[35]

Radio

News reports were required to be official state announcements, read exactly, and as the war in China went on, even entertainment programs addressed wartime conditions.[36]

The announcement of the war was made by radio, soon followed by an address from Tojo, who informed the people that in order to annihilate the enemy and ensure a stable Asia, a long war had to be anticipated.[37]

To take advantage of the radio's adaptability to events, "Morning Addresses" were made twice a month for schools.[26]

Short wave radios were used to broadcast anti-European propaganda to Southeast Asia even before the war.[38] Japan, fearful of foreign propaganda, had banned such receivers for Japanese, but built broadcasters for all the occupied countries to extol the benefits of Japanese rule and attack Europeans.[39] "Singing towers" or "singing trees" had loudspeakers on them to spread the broadcasts.[40]

Broadcasts to India urged revolt.[41]

Tokyo Rose's broadcasts were aimed at American troops.[41]

Negro propaganda operations

In an effort to exacerbate racial tensions in the United States, the Japanese enacted what was titled, "Negro Propaganda Operations."[42] This plan, created by Yasuichi Hikida, the director of Japanese propaganda for Black Americans, consisted of three areas.[42] First was gathering information pertaining to Black Americans and their struggles in America, second was the use of Black prisoners of war in the propaganda, and third was the use of short-wave radio broadcasts.[42] Through shortwave radio broadcasts, Japanese used their own radio announcers and African American POWs to spread propaganda to the United States. Broadcasts focused on U.S. news stories involving racial tension, such as the Detroit Race riots and lynchings.[43][44] For example, one broadcast commented, "notorious lynchings are a rare practice even among the most savage specimens of the human race."[42] In an effort to gain more listeners, POWs would be allowed to address family members back home.[43] The Japanese believed propaganda would be the most effective if they used African American POWs to communicate to African Americans back home. Using programs titled "Conversations about Real Black POW Experiences" and "Humanity Calls", POWs would speak on the conditions of war, and their treatment in the military. POWs with artistic strengths were used in plays and or songs that were broadcast back home.[42] The success of this propaganda is much debated, as only a small minority of people in America had shortwave radios.[43] Even so, some scholars believe that the Negro Propaganda Operations, "evoked a variety of responses within the Black community and the sum total of these reactions forced America’s government to improve conditions for Blacks in the military and society."[42] Even the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) saw the propaganda as, "...a media tool in the struggle against racial discrimination".[42] Despite these debates both sides agree that these programs were particularly dangerous because of their foundation in truth.[42][43][44]

Leaflets

Leaflets in China asked why they were not better defended after all the money they had spent.[45]

Leaflets were dropped by airplane on the Philippines, Malaya, and Indonesia, urging them to surrender as the Japanese would be better than the Europeans.[46] They were also dropped in India to encourage a revolt against British rule now that Great Britain was distracted.[41]

Slogans

Slogans were used throughout Japan for propaganda purpose.[47] They were used as patriotic exortion – "National Unity", "One Hundred Million With One Spirit" – and to urge frugality – "Away with frivolous entertainment!".[48]

Themes

Kokutai

Kokutai, meaning the uniqueness of the Japanese people in having a leader with spiritual origins, was officially promulgated by the government, including a text book sent about by the Ministry of Education.[25] The purpose of this instruction was to ensure that every child regarded himself first of all as a Japanese and was grateful for the "family polity" structure of government, with its apex in the emperor.[49] Indeed, little effort was made during the course of the war to explain to the Japanese people what it was fought for; instead, it was presented as a chance to rally about the emperor.[50]

In 1937, the pamphlet Kokutai no Hongi was written to explain the principle.[51] It clearly stated its purpose: to overcome social unrest and to develop a new Japan.[52] From this pamphlet, pupils were taught to put the nation before the self, and that they were part of the state and not separate from it.[53] The Ministry of Education promulgated it throughout the school system.[51]

In 1939, Taisei Yokusankai (Imperial Rule Assistance Association) was founded by the prime minister to "restore the spirit and virtues of old Japan".[54] When the number of patriotic associations during the war worried the government, they were folded into the IRAA, which used them to mobilize the nation and promote unity.[55]

In 1941, Shinmin no Michi was written to instruct the Japanese what to aspire to.[56] Ancient texts set forth the central precepts of loyalty and filial piety, which would throw aside selfishness and allow them to complete their "holy task."[57] It called for them to become "one hundred million hearts beating as one" – a call that would reappear in American anti-Japanese propaganda, though Shinmin no Michi explicitly said that many Japanese "failed" to act in this manner.[58] The obedience called for was to be blind and absolute.[59] The war would be a purifying experience to draw them back to the "pure and cloudless heart" of their inherent character that they had strayed from.[60] Their natural racial purity should be reflected in their unity.[61] Patriotic war songs seldom mentioned the enemy, and then only generically; the tone was elegiac, and the topic was purity and transcendence, often compared to cherry blossom.[62]

The final letters of kamikaze pilots expressed, above all, that their motivations were gratitude to Japan and to its Emperor as the embodiment of kokutai.[63] One letter, after praising Japanese history and the way of life their ancestors had passed down to them, and the Imperial family as the crystallization of Japan's splendour, concluded, "It is an honor to be able to give my life in defense of these beautiful and lofty things."[64]

Intellectuals at an "overcoming modernity" conference proclaimed that prior to the Meiji Restoration, Japan had been a classless society under a benevolent emperor, but the restoration had plunged the nation into Western materialism (an argument that ignored commercialism and ribald culture in the Tokugawa era), which had caused people to forget their nature, which the war would enable them to reclaim.[65]

Baseball, jazz, and other Western profligate ways were singled out in government propaganda to be abandoned for a pure spirit of sacrifice.[65]

This Yamato spirit would allow them to overcome the vast disproportion in fighting material.[66] This belief was so well indoctrinated that even as Allied victories overwhelmed the ability of the Japanese government to cover them up with lies, many Japanese refused to believe that "God's country" could be defeated.[67] The military government likewise fought on hopes that the casualty lists would undermine the Allied will to fight.[68] General Ushijami, addressing his troops in Okinawa, told them their greatest strength lay in moral superiority.[69] Even as American forces proceeded from victory to victory, Japanese propaganda claimed military superiority.[70] The attack on Iwo Jima was announced by the "Home and Empire" broadcast with uncommon praise of the American commanders but also the confident declaration that they must not leave the island alive.[71] The dying words of President Roosevelt were altered to "I have made a terrible mistake" and some editorials proclaimed it a punishment of Heaven.[72] American interrogators of prisoners found that they were unshakable in their conviction of Japan's sacred mission.[73] After the war, one Japanese doctor explained to American interrogators that the people of Japan had foolishly believed that the gods would indeed help them out of their predicament.[74]

This also gave them a sense of racial superiority to the Asian peoples they claimed to liberate, which did much to undermine Japanese propaganda for racial unity.[75] Their "bright and strong" souls made them the superior race, and therefore their proper place was in the leadership of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[76] Anyone not Japanese was an enemy – devilish, animalistic – including other Asian peoples such as the Chinese.[77] Strict racial segregation was maintained in conquered regions, and they were encouraged to think of themselves as "the world's foremost people."[78]

This race was, indeed, to be further improved with physical fitness and social-welfare programs, and population policies to increase their number.[79] A campaign to promote fertility, in order to produce future citizens, continued through 1942, and no efforts were made to recruit women to war work for this reason.[64] The slogan "Be fruitful and multiply" was used in campaigns.[80]

Rural life

Despite its military strength being dependent on industrialization, the regime glorified rural life.[81] The traditional rural and agricultural life was opposed to the modern city; proposals were made to fight the atomizing effects of cities by locating schools and factories in the countryside, to maintain the rural population.[79] Agrarianist rhetoric exulted village harmony, even while tenants and landlords were pitted against each other by war needs.[82]

Spiritual mobilization

The National Spiritual Mobilization Movement was formed from 74 organizations to rally the nation for a total war effort. It carried out such tasks as instructing schoolchildren on the "Holy war in China", and having women roll bandages for the war effort.[83]

Production

Even prior to the war, the organization Sanpo existed to explain the need to meet production quotas, even if sacrifices were needed; it did so with rallies, lectures, and panel discussion, and also set up programs to assist workers' lives to attract membership.[16]

Among the early victories was one that secured an oil field, giving Japan its own source for the first time; propaganda exulted that Japan was no longer a "have-not" nation.[84]

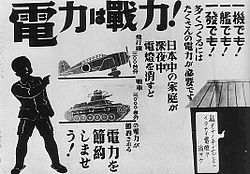

In 1943, as the American industrial juggernaut produced material superiority for the American forces, calls were made for a more war-like footing on part of the population, in particular in calls for increases in war materials.[85] The emphasis on training soldiers rather than arming them had left the armed forces dangerously ill-supplied after the heavy attrition.[86] Morning assemblies at factories had officers address the workers and enjoin them to meet their quotas.[87] The production levels were kept up, albeit at the price of extraordinary sacrifice.[88]

Privation

The government urged Japanese people to do without basic necessities (privation). For example, magazines gave advice on economizing on food and clothing as soon as war broke out with China.[12]

After the outbreak of war with the United States, early suggestions that the people enjoyed the victories too much and were not prepared for the long war ahead were not taken, and so early propaganda did not contain warnings.[89]

In 1944, propaganda endeavoured to warn the Japanese people of disasters to come, and install in them a spirit as in Saipan, to accept more privation for the war.[90] Articles were written claiming the Americans could not stage air-raids from Saipan, although since they could from China, they clearly could from Saipan; the purpose was to subtly warn of the dangers to come.[91] The actual bombing raids brought new meaning to the slogan "We are all equal."[92] Early songs proclaiming that the cities had iron defenses and it was an honor to defend the homeland quickly lost their luster.[93] Still, continued calls to sacrifice were honored; neighborhood association helped, as no one wanted to be seen quitting first.[94]

Accounts of self-sacrificing privation were common in the press: a teacher dressed in tatters who refused to wear a new shirt because all his friends are likewise tattered, and officers and governmental officials who made do without any form of heating.[95] This reflected the privation actually in society, where clothing was at premium and the work week was seven days long, with schooling cut to a minimum so that children could work.[96]

Hakkō ichiu

Like Nazi Germany's demands for Lebensraum, Japanese propaganda complained of being kept trapped in its own home waters.[25] Hakkō ichiu, "to bring the eight corners of the world under one roof", added a religious overtone to the theme.[25] It was based on the story of Emperor Jimmu, who had founded Japan, and finding five races on it, had made them all as "brothers of one family."[97] In 1940, the Japan Times and Mail recounted the story of Jimmu on the 2600 anniversary.[97]

The news of Hitler's success in Europe, followed by Mussolini's joining in the conflict, produced the slogan "Don't miss the bus!" as the European war gave them the opportunity to conquer Southeast Asia for its resources.[98]

On the outbreak of war, Tojo declared that as long as there remains a spirit of loyalty and patriotism under this policy, there was nothing to fear.[99]

An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus explicitly called for such expansion; although a secret document for use of the policy-makers, it laid out explicitly what is elsewhere hinted at in.[100] It explicitly laid out that the superior position of Japan in the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, showing the subordination of other nations was not forced by the war, but part of explicit policy.[101]

This was also justified on the grounds that the resource-poor Japanese could not count on any sources of raw material that they did not control themselves.[102] Propaganda stated that Japan was being strangled by "ABCD" – America, Britain, China, and Dutch East Indies—through trade embargoes and boycotts.[103] Even in preparation of the war, the newspapers reported that unless negotiations improved, Japan would be forced to engage in self-defense measures.[104]

Bushido

The samurai code bushido was pressed into service for indoctrination in militarism.[105] This was used to present war as purifying, and death a duty.[106] This worked to prevent surrenders, both of those who adhered to it, and of those who feared disgrace if they did not die.[106] This was presented as revitalizing traditional values and "transcending the modern."[107] War was presented as a purifying experience, albeit only for the Japanese.[108] Bushido would provide a spiritual shield to let soldiers fight to the end.[109] All soldiers were expected to adhere to it, although historically it had been the duty of higher ranked samurai and not common soldiers.[110]

As taught, it produced a reckless indifference to the technological side of warfare. Japan's production was a fraction of America's, making equipment difficult.[111] Officers declared themselves indifferent to radar, because they had perfectly good eyes.[112] The blue-eyed Americans would necessarily be inferior to the dark-eyed Japanese at night attacks.[113] At Imphal, the commander declared to his troops that it was a battle between their spiritual strength and the British material strength, a command which became famous as rubric of Japanese spirit.[114]

Soldiers were told that the bayonet was their central weapon, and many kept them affixed at all times.[115] Guns were treated as symbolic representations of martial spirit and loyalty, so any negligence regarding them was severely punished.[116]

As early as the Shanghai Incident, the principles of victory or death were already implemented, and much was made of a captured Japanese soldier who returned to the site of his capture to commit seppuku.[117] Three troopers who had blown themselves up on a section of barbed wire were lauded as "three human bombs" and featured in no less than six films, even though they may have died only because their fuses were too short.[118] Tojo himself, in a 1940 booklet, urged the spirit of self-sacrifice on soldiers, to not consider death.[119] It unquestionably contributed to the maltreatment of prisoners of war, who had performed the disgraceful act of surrender.[120] Another consequence was that nothing was done to train soldiers for captivity, with the result that Americans found Japanese prisoners much easier to get information from than the Japanese found American prisoners.[121]

In 1932, Akiko Yosano's poetry urged Japanese soldiers to endure sufferings in China and compared the dead soldiers to cherry blossoms, a traditional image that would be put to great use throughout the war.[12]

The emphasis on this tradition and the lack of a comparable military tradition in the United States led to an underestimating of American fighting spirit, which surprised Japanese forces at Midway, Bataan, and other Pacific War battles.[122] It also emphasized attack at the expense of defense.[123] Bushido argued for bold advances in the face of common sense, which was urged on the troops.[124]

The dead were treated as "war gods", starting with the nine submariners who died at Pearl Harbor (with the tenth, taken prisoner, never being mentioned in Japanese press).[125] The burials of and memorials for "hero gods" who had fallen in battle provided the Japanese public with news of battle that had not been otherwise released, as when a submarine attack on Sydney was revealed through burial of four who died; this propaganda frequently clashed with propaganda on victory.[126] Even years before the war, children had been instructed in school that dying for the emperor transformed one into a deity.[127] As the war turned, the spirit of bushido was invoked to urge that all depended on the firm and united soul of the nation.[128] Media were filled with stories of samurai, old and new.[129] Newspapers printed bidan, beautiful stories, about dead soldiers with their photographs and having a family member speak of them; before Pearl Harbor and the crushing casualties of the Pacific War, they endeavoured to get such a story for every fallen soldier.[130] While fighting in China, the casualties were low enough that individual cases were glorified.[118] Letters from "fallen heroes" became a staple of Japanese newspapers by 1944.[131]

Defeats were treated chiefly in terms of resistance to death. The Time magazine article on Saipan and the mass civilian suicides there was widely reported with the "awe-filled" enemy reports treated as evidence of the glory of sacrifice and the pride of Japanese women.[132] When the Battle of Attu was lost, attempts were made to make the more than two thousand Japanese deaths an inspirational epic for the fighting spirit of the nation.[133] Suicidal rushes were glorified as showing the Japanese spirit.[134] Arguments that the plans for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, involving all Japanese ships, would expose Japan to serious danger if they failed, were countered with the plea that the Navy be permitted to "bloom as flowers of death."[135] The last message of the forces on Peleliu was "Sakura, Sakura" – cherry blossoms.[136]

The first proposals of organized suicide attacks met resistance because while bushido called for a warrior to be always aware of death, he was not to view it as the sole end.[137] The Japanese Imperial Navy had not ordered any attacks it was impossible to survive; even with the midget submarines in the Pearl Harbor attack, plans had been made for rejoining the mother ship, if feasible.[138] The desperate straits brought about acceptance.[137] Propagandists immediately set about ennobling such deaths.[139] Such attacks were acclaimed as the true spirit of bushido,[140] and became an integral part of strategy with Okinawa.[141]

Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi addressed the first kamikaze (suicide attack) unit, telling them that their nobility of spirit would keep the homeland from ruin even in defeat.[142] The names of four sub-units within the Kamikaze Special Attack Force were Unit Shikishima, Unit Yamato, Unit Asahi, and Unit Yamazakura.[143] These names were taken from a patriotic poem (waka or tanka), Shikishima no Yamato-gokoro wo hito towaba, asahi ni niou yamazakura bana by the Japanese classical scholar, Motoori Norinaga.[144]

If someone asks about the Yamato spirit [Spirit of Old/True Japan] of Shikishima [a poetic name for Japan]—it is the flowers of yamazakura [mountain cherry blossom] that are fragrant in the Asahi [rising sun].

This also drew upon popular symbolism in Japan of the fall of the cherry blossom as a symbol of mortality.[145] These, and other kamikaze attackers, were acclaimed as national heroes.[146] Divers, prepared for such work in the event of the invasion of Japan, were given individual ensigns, to indicate they could replace an entire ship, and carefully separated so that they would die from their own handiwork rather than another's.[147]

The propaganda urging such deaths, and resistance to death, was issued in hopes that the bitter resistance would induce the Americans to offer terms.[148] When Togo made approaches to the Soviet Union, these were interpreted as asking for peace, which the newspapers instantly repudiated—they would not seek peace but win the war—a view enforced by the kempeitai, who arrested for any hint of "defeatism."[149] The army's manual on defending the homeland called for the slaughter of any Japanese who impeded the defense.[150]

Japanese propaganda of "fighting to the bitter end" and "the hundred-year war", indeed, led many Americans, beyond questions of hatred and racism, to conclude that a war of extermination might be the only possibility of victory, the question being whether the Japanese would surrender before such extermination was complete.[151]

Even after the atomic attacks and the Emperor's insistence that they surrender, Inaba Masao issued a statement urging the Army to fight to the bitter end; when other colonels informed him of a proclamation made to hint of the prospect of surrender to the population, they rushed to ensure Inaba's was broadcast, to create conflicting messages.[152] This caused consternation in the government for fear of American reaction, and to prevent delay, the surrender was sent out as a news story, in English and Morse code to prevent military censors from halting it.[153]

Intelligence

Early training for intelligence agents tried to infuse the service with the traditional mystery of spying in Japan, citing the spirit of the ninja.[154]

In China

In occupied China, textbooks were revised to omit tales of Japanese atrocities and instead focus on heroic Japanese figures, including one officer who divorced his wife before going to China, so that he could focus on the war, and she would be free of the burden of filial piety toward his parents, since he would certainly die.[27]

Against atrocity claims

Tight government censorship prevented the Japanese population from hearing of atrocities in China.[155]

When news of atrocities reached Western countries, Japan launched propaganda to combat it, both denying it and interviewing prisoners to counter it.[156] They were, it was proclaimed, being well-treated by virtue of bushido generosity.[157] The interviews were also described as being not propaganda but out of sympathy with the enemy, such sympathy as only bushido could inspire.[158] The effect on Americans was tempered by subtle messages imbedded by the prisoners, including such comments as the declaration they were allowed to continue to wear the clothes they had been captured in.[158]

As early as the Bataan Death March, the Japanese had The Manila Times claim that the prisoners were treated humanely and their death rate had to be attributed to the intransigence of the American commanders who did not surrender until their men were on the verge of death.[159] After the torture and execution of several of the Doolittle Raiders, the Nippon Times proclaimed the humane treatment of American and British prisoners of war in order to declare that British forces were treating German prisoners inhumanely.[160]

Anti-Western

The United States and Great Britain were attacked years before the war, with any Western idea conflicting with Japanese practice being labeled "dangerous thoughts."[38] They were attacked as materialistic and soulless, both in Japan and in short-wave broadcasts to Southeast Asia.[38] Not only were such thoughts censored through strict control of publishing, the government used various popular organizations to foment hostility to them.[161] Great Britain was attacked with particular fervor owing to its many colonies, and blamed for the continued stalemate in China.[162] Chiang Kai-shek was denounced as a Western puppet,[163] supplied through British and American exploitation of Southeast Asian colonies.[164] Militarists, hating the arms control treaties that allowed Japan only 3 ships for British and American 5, used "5-5-3" as a nationalistic slogan.[165] Furthermore, they wished to escape an international capitalist system dominated by British and American interests.[166]

Newspapers, in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor, kept up an ominous repetition of intransigence on the part of the United States.[167]

The news of the attack on Pearl Harbor resulted in newspapers staging a "Rally to Crush the United States and Great Britain."[168] When the government found the war songs too abstract and elegiac, it staged a nationwide competition for a song to a march tune with the title "Down with Britain and America."[169]

After such atrocities as the Bataan Death March, cruel treatment of prisoners of war was justified on the grounds they had sacrificed other people's lives but surrendered to save their own, and had acted with utmost selfishness throughout their campaign.[120]

The pamphlet The Psychology of the American Individual, addressed to soldiers, informed them that Americans had no thought of the glory of their ancestors, their posterity, or their family name, they were daredevils in search of publicity, they feared death and did not care what happened after it, they were liars and easily taken in by flattery and propaganda, and being materialistic, they relied on material superiority rather than spiritual incentive in battle.[170]

Praise of the enemy was treated as treason, and no newspaper could print anything mentioning the enemy favorably, no matter how much the Japanese forces found enemy combat spirit and effectiveness praiseworthy.[171]

Intellectuals promulgated anti-Western views with particular fervor.[172] A conference on "overcoming modernity" proclaimed the "world historical meaning" of the war was resistance to the Western cultural ideas imposed on Japan.[172] The Meiji Restoration had plunged the nation into Western materialism (an argument that ignored commercialism and ribald culture in the Tokugawa era), which had caused people to forget they were a classless society under a benevolent emperor, but the war would shake off these notions.[65] The government likewise urged the abandonment of Western ways—such as baseball and jazz—for a pure spirit of sacrifice.[65]

Officially, Japan did not present itself as completely anti-Western, because of the alliance with Italy and Germany, and to some policymakers, because such a claim was incompatible with Japan's high moral purpose. But as the alliance was both secure and solely of expedience, much antiwhite rhetoric was promulgated.[173] A propagandistic account of Germans in Java depicted them as grateful to be now under Japanese protection.[174] In the United States, Elmer Davis of the Office of War Information argued that this propaganda could be combated by deeds that counteracted this, but was unable to get support.[175]

Weakness

The Allies were also attacked as weak and effete, unable to sustain a long war, a view at first supported by a string of victories.[176] The lack of a warrior tradition such as bushido reinforced this belief.[177] The armed forces were told that American forces would not come to fight them, that Americans could not fight in the jungle and indeed could not stand warfare.[178] Accounts of prisoners of war depicted the Americans as cowardly and willing to do anything to gain favor.[179] Subordinates were actively encouraged to treat prisoners contemptuously, to foster feelings of superiority toward them.[180]

Both Americans and British were presented as figures of fun, resulting in serious weakness when complacency induced by propaganda met the actual enemy strength.[181]

Shortly prior to the Doolittle Raid, Radio Tokyo jeered at a foreign report of bombing on the grounds it was impossible.[182] The Doolittle Raid itself was minimized, reporting little damage, and concluding, correctly, that it had been carried out for American morale.[183]

Many Japanese pilots believed that their strength and American softness would result in their victory.[184] The ferocity and self-sacrificing attacks of American pilots at the Battle of Midway undermined the propaganda, as did the fighting at the Battle of Bataan and other Pacific battlefields.[122]

The surrender terms offered by the United States were scorned by the newspapers as ludicrous, urging that the government remain silent about them, which indeed, the government did, a traditional Japanese technique for dealing with the unacceptable.[185]

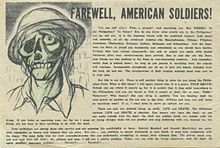

Against American morale

Most propaganda attacks against the American troops were aimed at morale.[56] Tokyo Rose gave sentimental broadcasts, designed to arouse homesickness.[41] She would also taunt the troops as suckers, with the prospect of their wives and sweethearts taking up with new men while they fought.[186] There were also broadcasts of prisoners of war speaking on the radio, to assure that they were being treated well; these were sandwiched between news reports of varying lengths, so that the entire broadcast had to be heard to be sure of hearing the prisoner.[187]

These programs were not well designed, as they assumed that the Americans did not want to fight, underestimating the psychological effect of Pearl Harbor, and that hostility to Roosevelt's domestic policies translated into hostility to his foreign policy.[188] Indeed, they believed that the Pearl Harbor attack would be regarded as a defensive act, forced on them by "Roosevelt and his clique".[188] American forces were less wed to the notion of "decisive battle" than Japanese were, and so the opening string of victories had less impact on them than expected.[189]

Furthermore, the prisoners who spoke often included subtle messages that undermined the anti-atrocity propaganda, stating they had been "allowed" the clothing they had worn when captured to make it clear that they had been given no new clothes.[158]

A pamphlet dropped on the forces on Okinawa declared that President Roosevelt's death had been caused by the extensive damage the Japanese had inflicted on American ships, which would continue until the ships were all sunk, and the American forces thus orphaned.[190] One soldier, reading it while the ships were bombarding the shore, asked where they thought the gunfire was coming from.[190]

Anti-communist

Communism was enumerated among the Western dangerous ideas. However, during the invasion of China, Japanese propaganda to the United States played on American anti-communism to win support.[191] It[clarification needed] was also offered to the Japanese people as a way of forging a bulwark against communism.[163] Propaganda was also used to demonise the Chinese Communist Party.

Allied atrocities

Shinmin no Michi, the Path of the Subject, discussed American historical atrocities[56] and presented Western history as brutal wars, exploitation, and destructive values.[23] Its colonialism was based on its destructive individualism, materialism, utilitarianism, and liberalism, all which allowed the strong to prey on the weak.[192]

While minimizing the effect of the Doolittle Raid, propaganda also depicted the raiders as inhuman demons attacking civilians.[193] Shortly after those of the raiders who had been captured had been tortured, and some executed, the Nippon Times denounced British treatment of German prisoners of war, claiming that American and British prisoners held by Japan were being treated in accordance with international law.[160]

Allied war purposes were presented as annihilation.[194] Japanese civilians were told that the Americans would commit rape, torture, and murder and they therefore were to kill themselves rather than surrender; on Saipan and Okinawa, large majorities of the civilian population did commit suicide or kill each other before the American victory.[195] Those captured on Saipan were often terrified of their captors, particularly of the black soldiers, although this was not solely due to propaganda, but because many had never seen blacks before.[196] The demand for unconditional surrender was heavily exploited.[197] Interrogated prisoners reported that this propaganda was widely believed and therefore people would resist to the death.[34]

Accounts of American soldiers murdering German prisoners of war were also told, regardless of accuracy.[198]

Much play was made of American soldiers desecrating the bodies of the dead, omitting that such acts were condemned by both military authorities and from America pulpits.[199] That President Roosevelt was presented with a gift from a Japanese soldier's forearm was reported, but not that he refused it and argued for a decent burial.[200]

In American propaganda, much was made of Japanese calls to devotion to death.[201] Some soldiers attacked civilians, on the grounds they would not surrender, and which in turn served as grist for Japanese propaganda about American atrocities.[202]

Even before the American pamphlets warning of the great power of atomic explosions, newspapers commenting on the atomic attacks reported that the bombs could not be taken lightly; The Nippon Times reported that it was clearly intended to kill many innocent people, to end the war quickly, and others proclaimed it a moral outrage.[203]

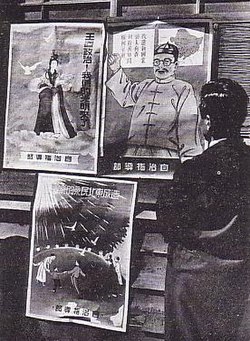

To the occupied countries

Extensive use of posters was made in China, to endeavour to convince the Chinese that the Europeans were enemies, especially the Americans and British.[204] Much was made of the opium trade.[204]

Similarly, the Philippines were propagandized about "American exploitation," "American Imperialism," and "American tyranny," and blame was laid on the United States for starting the war.[56] They were assured that they were not Japan's enemies, and that the American forces would not return.[5][56] The effect of this was considerably undermined by the actions of the Japanese Army, and the Filipinos soon wanted the Americans to return to free them from the Japanese.[56] Black propaganda posed as American instructions to avoid venereal disease by having sexual intercourse with wives or other respectable Filipina women rather than prostitutes.[56]

After the fall of Singapore, American and British were sent as prisoners to Korea to eradicate Korean admiration for them.[205] Ragged prisoners of war, brought to Korea as forced labor, were also marched through the streets, to show how the European forces had fallen.[206]

In the occupied countries short-wave radios attacked Europeans, particularly "White Australia", which, broadcasts claimed, could support 100 million instead of the current 7 million, if the industrious Asians were allowed to make it bloom.[39]

Broadcasts and leaflets urged India to revolt against British rule now that Great Britain was distracted.[41] Other leaflets and posters, aimed at Allied forces of different nationalities, attempted to drive a wedge between them by attacking other Allied countries.[56]

Antisemitic

This Western hegemony was presented, sometimes, as being masterminded by Jews.[60] Especially in the early years of the war, a spate of anti-Jewish propaganda was produced, which appears to be the effect of the Nazi alliance.[207]

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

During the war, "Asia for the Asians" was a widespread slogan, though undermined by brutal Japanese treatment in occupied countries.[208] This was in service of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, where the new Japanese empire was presented as an Asian equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine.[5][209] The regions of Asia, it was argued, were as essential to Japan as Latin America was to the United States.[210]

This was initially, while plausible, very popular among the occupied nations.[5][211] Japanese victories were initially cheered in support of this aim.[212] Many Japanese remained convinced, throughout the war, that the Sphere was idealistic, offering slogans in a newspaper competition, praising the sphere for constructive efforts and peace.[213]

During the war with China, the prime minister announced on radio they were seeking only a new order to ensure the stability of East Asia, unfortunately prevented because Chiang Kai-shek was a Western puppet.[163] The failure to win the Second Sino-Japanese War was blamed on British and American exploitation of Southeast Asian colonies to supply the Chinese, even though the Chinese received far more assistance from the Soviet Union.[164]

Later, pamphlets were dropped by airplane on the Philippines, Malaya, and Indonesia, urging them to join this movement.[46] Mutual cultural societies were founded in all conquered nations to ingratiate with the natives and try to supplant English with Japanese as the commonly used language.[214] Multi-lingual pamphlets depicted many Asians marching or working together in happy unity, with the flags of all the nations and a map depicting the intended sphere.[215] Others proclaimed that they had given independent governments to the countries they occupied, a claim undermined by the lack of power given these puppet governments.[56] In Thailand, a street was built to demonstrate it, to be filled with modern buildings and shops, but nine-tenths of it consisted of false fronts.[216]

The Greater East Asia Conference was highly publicized.[217] Tojo greeted them with a speech praising the "spiritual essence" of Asia, as opposed to the "materialistic civilization" of the West.[218] At it Ba Maw declared that his Asian blood had always called out to other Asians, and that it was not time to think with minds, but with blood, and many other Asian leaders supported Japan in terms of an East vs. West conflict of bloods.[217] Japanese oppression and racial pretensions slowly undermined this dream.[219]

The booklet Read This and the War is Won was intended for the Japanese army.[23] It presented colonialism as a tiny group of colonists living in luxury by burdening Asians; because ties of blood connect them to Japanese, and Asians had been weakened by colonialism, it was Japan's place to "make men of them again."[24]

China

In China, leaflets were dropped arguing that the "mandate of heaven" had clearly been lost, so that authority moved to the new leaders.[56] Propaganda also spoke of the benefits of the "kingly way" (王道 wang tao or, in Japanese odo) as a solution to both nationalism and radicalism.[220]

Philippines

The Philippines were their first target after Pearl Harbor, and instructions to propagandists called for rousing "the spirit of the Far East" and inspiring them with militarism to fight beside the Japanese.[56] "Surrender cards" were dropped to allow soldiers to surrender safely by handing over a card.[56] Jorge B. Vargas, the Chairman of the Executive Committee, Provisional Philippine Council of State, signed one leaflet that was dropped urging surrender.[56]

Korea

Korea was annexed in 1910. The Governor-General of Korea[which?] said that the colony's economic progress in the ensuing 30 years was because its Japanese administrators had devoted themselves to its benefit.[221]

The Japanese attempted to co-opt the Koreans, urging them to view themselves as part of one "imperial race" with Japan, and even presenting themselves as rescuing a nation too long under the shadow of China.[222]

[better source needed]

However, native Koreans lost their estate, society and position, which encouraged resistance.[223]

India

The Battle of Imphal was fought, in part, to show the Indian National Army to the Indians, in hopes of provoking a revolt against the Raj.[224]

Self-defense

Propaganda declared that the war had been forced on them in self-defense. As early as the Manchurian Incident, the mass media uncriticially spread the report that the Chinese had caused the explosion, attacking Japan's rights and interests, and therefore the Japanese must defend their rights, even at great sacrifice.[225] This argument was made even to the League of Nations: they were only trying to prevent anti-Japanese activities by the Guomindang.[226]

Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, newspapers reported that unless negotiations improved, Japan would be forced to engage in self-defense measures.[104] Indeed, after the attack, propaganda to American forces operated on the assumption that Americans would regard Pearl Harbor as a defensive act, forced on them by "Roosevelt and his clique".[188]

Victories

For propaganda purposes, defeats were presented at home as great victories.[50] Much was made of Japan's 2,600-year history without defeats.[227] The wars of 1895 and 1904 were presented by historians as overwhelming triumphs instead of narrowly won.[228] For a long time, the armed forces held to the belief that a string of victories would demoralize the Americans sufficiently for a negotiated peace.[229]

This began with the claims about the war in China.[230] It continued with newspaper exultation over the attack on Pearl Harbor.[231] and continued with the string of early Japanese successes.[232] This produced an exuberance in the people that did not brace them for a long war, but suggestions that it be tempered were not accepted.[89] Even in the early stages, exaggerated claims were made, such as that Hawaii was in danger of starvation even though the Japanese submarines were not raiding commerce, as would have been needed to bring this about.[233] The capture of Singapore was triumphantly declared as deciding the general situation of the war.[234] The Doolittle Raid produced considerable shock and efforts to counter the impact were made.[235] The army, after some victories, clearly began to believe its own propaganda.[236] Very few statements even hinted that more was needed prior to victory.[237]

The prolonged resistance at Bataan was in part enabled by orders that required a spectacular victory for propaganda points, resulting in Japanese forces taking Manila while American forces entrenched.[238] Dogged American resistance at Corregidor resulted in occasional declarations that its defeat was near, followed by weeks of silence.[239] The Battle of Coral Sea was presented as a victory rather than inconclusive, exaggerating American losses and understating Japanese ones.[240] Indeed, it was presented as a sweeping triumph, rather than the marginal tactical victory that could reasonably be claimed.[241] Declarations were made that the battle had rendered the Americans panic-stricken, when in fact, they had also proclaimed it a victory.[242]

The attack on Midway was rendered crucial by the Doolittle Raid, which had sneaked through the defensive perimeter at that point and, while not causing serious damage, had caused humiliation and propaganda difficulties.[243] The clear defeat at the Battle of Midway continued this pattern.[50] Newspapers were informed only of American damage, with the Japanese losses entirely omitted.[244] The survivors of the lost ships were sworn to silence and packed off to distant fronts to prevent the truth becoming known.[245] Even Tojo was not informed of the truth until a month after the battle.[246]

The word "retreat" was never used, even to the troops.[247] In 1943, the army invented a new verb tenshin, to march elsewhere, to avoid referring to their forces as retreating.[50] Japanese who used the term "strategic retreat" were warned against doing so.[248] One reason for the execution of captured American aircrew was to hide their presence, evidence that the Japanese forces were falling back.[249]

By the time of the Guadalcanal Campaign newspapers were no longer covering their first pages with victories but adding stories about the battles in Europe and the Prosperity Sphere, but some battles had to be presented as victories.[250] Reporters wrote articles as if they were winning.[251] Japanese authorities published accounts boasting of the casualties inflicted before withdrawal.[252] The Battle of the Eastern Solomons was reported not only exaggerating American damage, but claiming that the carrier Hornet had been sunk, thus taking revenge for its part in the Doolittle Raid, when in fact Hornet had not been in the battle.[253] The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, while a Japanese tactical victory, gained time for the Americans on Guadalcanal and inflicted heavy losses on Japanese aircraft; it was considered so momentous that it was praised in an imperial rescript.[254]

However, by 1943, the Japanese population was aware of the stark difference between the crude propaganda and the facts.[255] The death of Isoroku Yamamoto inflicted a severe blow.[133] It was followed by defeat at the Battle of Attu, which propaganda could not make inspirational.[133]

Accounts of the battle at Saipan concentrated on the fighting spirit and the heavy American casualties, but familiarity with geography would demonstrate that the battles slowly progressed northwards as the American forces advanced, and the reports stopped with the final battle, which was not reported.[256] Reports of "annihilation" did not prevent American forces from continuing to fight.[257] Furthermore, newspapers were allowed to speculate about the future of the war as long as they did not predict defeat or otherwise evince disloyalty; the truth could be discerned from their presuppositions.[258]

After Saipan had led to the resignation of Tojo as prime minister, an accurate account of the fall of Saipan was published by the army and navy, including the nearly total loss of all Japanese soldiers and civilians on the island, and the use of "human bullets", leading many to conclude that the war was lost.[259] This was the first uncensored war news they had issued since 1938, during the war with China.[83] The simultaneous and disastrous Battle of Philippine Sea was still obfuscated in the old manner.[259] A battle off Formosa was declared a victory, and a holiday declared, when in fact Americans had inflicted heavy damage and drawn off planes needed to defend the Philippines.[260] Inexperienced pilots reported crippling attacks on the ships of United States Third Fleet shortly prior to the Battle of Leyte, which were accepted at face value when the pilots had in fact not sunk a single ship.[261] The first suicide attacks were likewise presented as successful in causing damage, in contradiction of the facts.[262]

A shot-down B-29 was displayed along with the boast that it was one of hundreds.[91]

Peace

When the offer to surrender had been made, Kōichi Kido showed the Emperor the American pamphlets telling of the offer and stated that uninformed soldiers might start an uprising if this fell into their hands.[263] The Cabinet agreed that the proclamation had to come from the emperor himself, although in concession to his position it was decided to make it a recording rather than a live broadcast.[264] The Kyūjō Incident, attempting to prevent the broadcast, failed.[265]

See also

- American propaganda during World War II

- British propaganda during World War II

- Jikyoku Iinkai

- Nazi propaganda

- Propaganda of Fascist Italy

References

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 441 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 442 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ a b c Ward, Robert Spencer (1945). Asia for the Asiatics?: The Techniques of Japanese Occupation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Baskett, Michael (2008). The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- ^ a b c Desser, D. (1995). "From the opium war to the pacific war: Japanese propaganda films of world war II." Film History 7(1), 32-48.

- ^ Kushner, Barak (2006). The Thought War: Japanese Imperial Propaganda. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Baskett, Michael (2005). "Rediscovering and remembering Manchukuo in Japanese "Goodwill Films" in Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire ed., Mariko Tamanoi. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 120-134.

- ^ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p250 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b c d Brcak, N., & Pavia, J. R. (1994). "Racism in japanese and U.S. wartime propaganda." Historian 56(4), 671.

- ^ Baskett, Michael (2009). "All Beautiful Fascists? Axis Film Culture in Imperial Japan" in The Culture of Japanese Fascismed. Alan Tansman. Duke University Press.

- ^ a b c James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 427 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 490-1 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p66 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ a b Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan p 643 ISBN 0-674-00334-9

- ^ a b c James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 491 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan p 644 ISBN 0-674-00334-9

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p67 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p68 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p95 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p96 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ "Die for Japan: Wartime Propaganda Kamishibai (paper plays; 国策紙芝居)". Dym Sensei. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ a b c d John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p24 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ a b John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p24-5 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ a b c d Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p246 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p246, 248 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 156 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 173 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p172 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 257-8 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p635 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ a b James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 466 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p343 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ a b c Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p41 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p355 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 467 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 228 Random House New York 1970

- ^ a b c Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p249 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p255 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p255-6 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b c d e Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p256 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b c d e f g h Masaharu, Sato, and Barak Kushner (1999). "'Negro propaganda operations’: Japan’s short-wave radio broadcasts for world war II black Americans." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 19(1), 5-26.

- ^ a b c d Menefee, Selden C. (1943) "Japan’s psychological war." Social Forces 21(4), 425-436.

- ^ a b Padover, Saul K. (1943) "Japanese race propaganda." The Public Opinion Quarterly 7(2), 191-204.

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 239 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ a b Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p253 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p174 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p633 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan p 600-1 ISBN 0-674-00334-9

- ^ a b c d Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, p 299 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ a b Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p199, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 465-6 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ W. G. Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan, p 187 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 189 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 493 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "JAPANESE PSYOP DURING WWII"

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p27 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p30-1 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ "Zen and the Art of Divebombing"

- ^ a b John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p225 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p439-40 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p213-4 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p309 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ a b James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 505 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ a b c d Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p219-20, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p 34 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p262 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ "Japan in World War II Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p285 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 368 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 655 Random House New York 1970

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 701 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan p 655 ISBN 0-674-00334-9

- ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, p 302 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p46 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p211 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p 32 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p 37 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ a b John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p271 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p173 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Michael Burleigh, Moral Combat: Good And Evil In World War II, p 13 ISBN 978-0-06-058097-1

- ^ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p215, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ a b Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 257 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 247 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 332 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, p 222-3 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p190 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 523 Random House New York 1970

- ^ a b John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 258 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 362 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ a b Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 363 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 670 Random House New York 1970

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 745 Random House New York 1970

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 509 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 371-2 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 523-4 Random House New York 1970

- ^ a b John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p223 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 60 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 231 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p262-3 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p263-4 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p438 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 215 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ a b Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 219 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ "No Surrender: Background History"

- ^ a b David Powers, "Japan: No Surrender in World War Two"

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p1 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p216 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won p 6 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p264 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p35 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p47 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Masanori Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy p25 New York W.W. Norton & Company 1956

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 413 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 350 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 350-1 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 100-1 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ a b Michael Burleigh, Moral Combat: Good And Evil In World War II, p 16 ISBN 978-0-06-058097-1

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 198 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ a b John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 301 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 382 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ a b William L. O'Neill, A Democracy At War: America's Fight At Home and Abroad in World War II, p 125, 127 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 386 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 428 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p307 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 317 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 258 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 334 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 334-5 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p214 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 369-70 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p339 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ a b c John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 444 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook, Japan At War: An Oral History p263-4 ISBN 1-56584-014-3

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 539 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 424 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ a b Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 356 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Masanori Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy p161-2 New York W.W. Norton & Company 1956

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p167 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 360 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 713 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p284 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p289 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p289-90 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ Ivan Morris, The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, p290 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p172 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 389 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 396 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 397 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p439 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p57 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 815-6 Random House New York 1970

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 816 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 378 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 449 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 256-7 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 256 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ a b c Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 257 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 300 Random House New York 1970

- ^ a b John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 598 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Beasley, William G.,The Rise of Modern Japan, p 185 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p639 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ a b c James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 451 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ a b James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 471 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ William L. O'Neill, A Democracy At War: America's Fight At Home and Abroad in World War II, p 52 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 460 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 189-90 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 243-4 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p214 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 651 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Masanori Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy p125 New York W.W. Norton & Company 1956

- ^ a b Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p219, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p206-7 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 259 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 453 Random House New York 1970

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p36 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ William L. O'Neill, A Democracy At War: America's Fight At Home and Abroad in World War II, p 125-6 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, p 317 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 258 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 476 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 418 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 305 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 273-4 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ William L. O'Neill, A Democracy At War: America's Fight At Home and Abroad in World War II, p 125 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p471-2 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45 p 12 ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3

- ^ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p256-7 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ a b c Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p257 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 394 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- ^ a b John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 702 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 165 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p26-7 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 310 Random House New York 1970

- ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, p 309-310 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p45 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 515-6, 563 Random House New York 1970