Japan Crude Cocktail

| Country | Japan, South Korea, India, Taiwan, China |

|---|---|

| Refinery details | |

| Commissioned | 1950s |

The Japan Crude Cocktail (JCC) is the informal nickname given to the pricing index of Crude Oil used in most East Asian countries.[1] The JCC is the average price of customs-cleared crude oil imports into Japan and is published by the Petroleum Association of Japan.[2] The official name of the JCC is the Japan Customs-cleared Crude Oil Price.[3] The valuation of the JCC closely reflects the market state of supply and demand. Clear fluctuations in JCC pricing can be linked to distinct events such as the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis and the 2011 Fukushima Disaster.[4]

The JCC was historically the main index to price Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) contracts as no global benchmark existed. However, as JCC is based on oil prices as opposed to gas, there has been a rise in objection to its use. In Europe and most North American nations, LNG pricing has shifted from use of the JCC to gas-based indexes (e.g. Henry Hub).[3]

Historical Development

Following the end of World War II, Japan's rapid industrialisation made them one of the largest energy consumers.[5] However, Japan's limited domestic resources of fuel means the country relies heavily on imports. In the 1950s, the Japan Crude Cocktail was formulated to create a pricing index of customs-cleared crude oil imports.[1]

The Customs-cleared crude oils applicable have the following Harmonised System codes; 2709.00 100, 2709.00 900, 2710.19 162, 2710.19 164, 2710.19 166, 2710.19 169, 2710.19 172, 2710.19 174, 2710.19.179.[2]

Petroleum Association of Japan

This Petroleum Association of Japan (PAJ) was established in 1955,[6] around the time of the JCC development. The PAJ consists of 11 refiners and primary distributors in Japan.[7] They are responsible for providing central information on the petroleum industry for the public, as well as advocating, researching and enhancing communication among the public and oil companies.

The 11 refiners and primary distributors of the PAJ are Idemitsu Kosan, Cosmo Oil Marketing, TOA Oil, ENEOS, KASHIMA Oil, Kygnus Sekiyu, Taiyo Oil Company, Showa Yokkaichi Sekiyu, Fuji Oil Company, Seibu Oil and Cosmo Oil Company.[8]

The PAJ publish a range of oil statistics monthly on their website, including the JCC.

Users

LNG Contracts

Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) contracts are legal agreements for the sale and purchase of LNG between sellers and buyers[9] LNG is an energy commodity, just like crude oil, allowing for a price relationship between the two.[10]

LNG contract pricing has been based on the JCC index since the 1970s.[11] LNG was initially introduced in Japan as an energy substitute to reduce the country's high dependence on oil.[12] In turn, this guaranteed that gas could remain competitive with oil by having similar pricing. The JCC is used as the pricing index in LNG contracts mainly in Asia Pacific (APAC) and Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA).[2] For example, the index is heavily used in China, South Korea, India, Taiwan.[3]

JCC Formula

JCC

The JCC pricing index is based on the average price of customs-cleared crude oil imports into Japan. The Ministry of Finance sector within the Japanese government publishes the data used to calculate the JCC each month.$X = The total value of customs cleared crude oil imports

Y = The total volume of customs cleared crude oil imports

LNG Contracts

The JCC figure is then used to generate the price of LNG contracts using the following formula.[13]

PLNG = The Cost, Insurance and Freight (CIF) price of LNG

a = The extent to which the PLNG changes in response to changes in the JCC, also known as the ‘slope’

b = The additional freight charges, discounts or premiums incurred. This constant term is determined through contract negotiations.

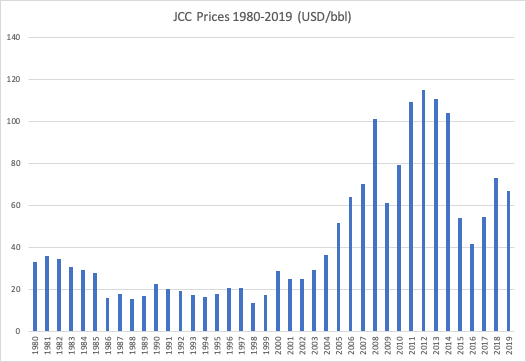

Pricing, 1980-2019

The Japan Crude Cocktail prices are given in USD per barrel (USD/bbl). JCC prices are available from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[14]

The JCC has had continuous price fluctuations over its history, whilst still steadily increasing. From the raw data and graph, the two major spikes in prices can be seen in 2008 and 2011–12. A comparatively dramatic price low can be observed in 2016.[14]

| Year | Price USD/bbl |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 33.11 |

| 1981 | 35.92 |

| 1982 | 34.57 |

| 1983 | 30.47 |

| 1984 | 29.35 |

| 1985 | 27.9 |

| 1986 | 16.08 |

| 1987 | 17.99 |

| 1988 | 15.47 |

| 1989 | 16.91 |

| 1990 | 22.64 |

| 1991 | 20.14 |

| 1992 | 19.3 |

| 1993 | 17.47 |

| 1994 | 16.48 |

| 1995 | 18.02 |

| 1996 | 20.55 |

| 1997 | 20.55 |

| 1998 | 13.68 |

| 1999 | 17.38 |

| 2000 | 28.72 |

| 2001 | 25.01 |

| 2002 | 24.96 |

| 2003 | 29.26 |

| 2004 | 36.59 |

| 2005 | 51.57 |

| 2006 | 64.03 |

| 2007 | 70.09 |

| 2008 | 100.98 |

| 2009 | 61.29 |

| 2010 | 79.43 |

| 2011 | 109.3 |

| 2012 | 114.75 |

| 2013 | 110.61 |

| 2014 | 104.16 |

| 2015 | 54.2 |

| 2016 | 41.79 |

| 2017 | 54.42 |

| 2018 | 72.85 |

| 2019 | 66.78 |

Price Variations

First Oil Crisis 1973

The Yom Kippur War between Israel and Arab nation resulted in the first oil crisis internationally. In October 1973, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) started an oil embargo, targeted at nations thought to be supporting Israel during the conflict. The countries primarily targeted were Japan, US, Canada, UK and the Netherlands. Originally, oil exports from Arab nations were to be reduced by 5% monthly until Israel met the demands of the Arab nations.[15] However, in December, a full embargo was put in place, restricting all trade of oil. Following the events of this first oil crisis, Japan became more aware to their vulnerability to external oil prices and began focusing on increasing their self-dependence on their own natural resources and energy sources. Their whole oil industry was redesigned.

The first oil crisis resulted in recession, inflation and a trade deficit in Japan as all purchasing power was removed from Japan and given to the Arab oil producing nations.[16] In regard to the JCC, the ban on supply heavily increased import prices. Crude oil import prices rose by 300% globally. In 1970, almost 85% of Japan's crude oil imports came from the Middle East.[17]

Global Financial Crisis 2007-2008

The Global Financial Crisis 2007-2008 (GFC) was one of the greatest periods of extreme economic stress since the 1930s. Thousands of businesses suffered heavy losses and/or bankruptcy, with millions of people losing their jobs. The intense period of recession's influential impact on the JCC is highly notable, observed in the first spike seen in 'Crude oil import Prices in Japan 1980-2019' graph.

Worldwide, oil demand heavily relies upon income rather than market demand.[18] When Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is in elevated periods, disposable income is greater, allowing for increased purchase of goods. This creates dependent relationship oil consumption growth rates have with GDP growth rates. It can be observed that in periods of high GDP growth rate, oil consumption growth rates soon also increase. The same can be said for decreases in GDP grow rates.

The period of 2008-2009 saw a decline in both GDP growth rate and oil consumption growth rate in Japan. JCC spiked in 2008 at US$100.98/bbl before dramatically declining in 2009 to $61.29. This aligns with the economic concepts of recession. In times of recession, demand dramatically reduces, driving down prices for suppliers

In the recent years leading to the GFC, China's crude oil imports exponentially increased. With greater economic resources, China began to dominate the consumption of crude oil, reducing crude oil supply available and thus consumption for other nations. From 2005 to 2007, Japan's crude oil consumption per day reduced by 318,000 barrels.[18] Limited supply, drives prices up, reflected in the 2005-2007 JCC increased from US$51.57/bbl to US$70.09/bbl.

Fukushima Disaster 2011

In March 2011, the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami hit the east coast of Japan. The generators at the Fukushima Nuclear Power plant nearby shut down automatically after detecting the earthquake.[19] The shortly followed tsunami flooded the nuclear power plants, destroying the reactors and releasing radiation. This destruction of the nuclear plant is known as the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster.[20]

All 50 reactors were recorded as offline by 2012. One fifth of Japan's energy generating capacity was lost as a result.[21] The loss of domestic energy sources created immense pressure on the Japanese economy as demand for LNG imports rose substantially.[22] In the initial years and immediately after the disaster, LNG imports accounted for 40% of Japan's power.[4] The sudden steep incline in demand rapidly drove prices. From 2010 to 2012, JCC rose from US$79.43/bbl to US$114.75/bbl.

It wasn't until 2015 when some of Japan's nuclear plants were restarted, that JCC prices to return to a lower price.

COVID-19 Pandemic

In 2020, the COVID-19 exponentially infected all parts of the globe, creating an international health outbreak and pandemic. Many nations were sent into lockdown as a result of the health risks. The World Bank stated that the "global economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has driven most commodity prices down and is expected to result in substantially lower prices over 2020".[23] This is due to the mass mandatory quarantine that restricted any movement of people, domestically and internationally. Lockdown created a halt in economic activity as people were unable to leave home to attend jobs or to support the economy (e.g. tourism, travel, shopping),[24][1] affecting both supply and demand. Inability for movement impacted the oil industry heavily as travel restrictions correlate to a cut in demand for jet fuel.[25] The closure of factories and reduced commute amid the crisis further reduced need for fuels.

In Japan, crude oil imports dropped by 25% in 2020, with only 2.28 million barrels per day imported in May 2020.[26] This figure is the lowest it has been in 53 years. This is a direct result of the abrupt freeze of production and supply amid the pandemic. Price of the JCC during the pandemic can be observed in the table generated below.[27] Prices fell to US$24.55/bb in June 2020 as demand for crude oil in Japan dramatically declined.

| Month (2020) | Price of Crude Oil USD/bb |

|---|---|

| January | 70.33 |

| February | 70.63 |

| March | 62.16 |

| April | 42.21 |

| May | 24.96 |

| June | 24.55 |

| July | 32.78 |

| August | 43.42 |

| September | |

| October | |

| November | |

| December |

Future Directions of JCC

The JCC price index was established in the early 1950s to reflect the market fundamentals of the time. However, as these have shifted over time, the JCC has failed to keep up to date with these changes.[12] After the impacts of the Fukushima Disaster, JCC reached an all-time high of US$114.75/bbl in 2014. Since this event, there has been growing unrest amongst users of the index.[28]

The main concern for users is that JCC is predominately used for pricing LNG contracts. Oil-based LNG contracts are priced considerably higher than alternatives as they reflect the price of oil imports.[28] In European and North American nations, LNG pricing has already shifted from an oil-based pricing index to hub-based pricing such as the Henry Hub and Dutch Title Transfer. However, most East Asian nations continue to use the JCC to price LNG. cheaper alternative. In 2014, senior gas analyst at the Institute of Energy Economics, Hiroshi Hashimoto, stated “the aim is to link 100% to Henry Hub prices, rather than JCC as has been the custom globally”.[29]

In addition to the cheaper prices that a gas-based index would offer, the shift would also remove the current time lag between crude oil and LNG prices. The LNG pricing formula in Japan is . (See JCC formula subheading). JCC prices take on average 5 months to be reflected in LNG contract prices.[30] This is due to the fact that the JCC is derived from the price of crude oil when imported into Japan. However, this figure can greatly change from the international market price on the day of transportation. By shifting to a gas-based pricing index, LNG contracts can be based on current market value, remaining competitive with other indexes.

References

- ^ a b c Stern, Jonathon (2020). "A Comparative History of Oil and Gas Markets and Prices: is 2020 just an extreme cyclical event or an acceleration of the energy transition?" (PDF). OIES Energy Insight: 1–22 – via University of Oxford.

- ^ a b c CME Group (2020). "FAQ: Japan Crude Cocktail".

- ^ a b c Stern, Jonathon (2014). "Challengest o JCC Pricing in Asian LNG Markets" (PDF). Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

- ^ a b Nikkei (2017). "Japanese LNG prices cool off 6 years after Fukushima". Nikkei.

- ^ US Energy Information Administration (2020). "Japan". US Energy Information Administration.

- ^ Knoema (2020). "Petroleum Association of Japan". Knoema.

- ^ Petroleum Association of Japan (2015). "About PAJ". Petroleum Association of Japan.

- ^ Petroleum Association of Japan (2015). "Members of PAJ". Petroleum Association of Japan.

- ^ Law Insider (2020). "Definition of LNG Contracts". Law Insider.

- ^ Andrew, Hecht (2020). "Crude Oil vs. Natural Gas". The Balance.

- ^ Shi, Xungpeng (2016). "Gas and LNG pricing and trading hub in East Asia: An introduction". Natural Gas Industry B. 3 (4): 352–356. Bibcode:2016NGIB....3..352S. doi:10.1016/j.ngib.2016.12.008. hdl:10453/145718.

- ^ a b Xunpeng, Shi (2016). "Gas and LNG Pricing and Trading Hub in East Asia: An introduction". Natural Gas Industry B. 3 (4): 352. Bibcode:2016NGIB....3..352S. doi:10.1016/j.ngib.2016.12.008. hdl:10453/145718.

- ^ Energy Information Administration (2017). "Perspectives on the Development of LNG Market Hubs in the Asia Pacific Region" (PDF).

- ^ a b OECD (2020). "Crude oil import prices". OECD Library.

- ^ History (2010). "OPEC enacts oil embargo". History.com.

- ^ Marius, Mihut (2012). "First Oil Shock Impact on the Japanese Economy". Procedia Economics and Finance. 3: 1042–1048. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(12)00271-7.

- ^ Nippon (2019). "Japan Still Reliant on Middle Eastern Oil". Nipon.com.

- ^ a b James, Hamilton (2009). "Causes and Consequences of the Oil Shock of 2007–08" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2009: 215–283. doi:10.1353/eca.0.0047. S2CID 201760160.

- ^ World Nuclear Association (2020). "Fukushima Daiichi Accident". World Nuclear Association.

- ^ Lonsdorf, Kat (2020). "How The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Affected The Energy Industry In Japan". NPR.

- ^ Hayashi, Masatsugu (2013). "The Fukushima nuclear accident and its effect on global energy security". Energy Policy. 59: 102–111. Bibcode:2013EnPol..59..102H. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.11.046 – via Science Direct.

- ^ ADBI Institute (2017). "Impact of Fukushima Nuclear Disaster on Oil-Consuming Sectors of Japan" (PDF).

- ^ Felsenthal, Mark (2020). "Most Commodity Prices to Drop in 2020 As Coronavirus Depresses Demand and Disrupts Supply". The World Bank.

- ^ PwC (2020). "The possible economic consequences of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic" (PDF). PwC.

- ^ Sell, Christopher (2020). "How the Pandemic Wiped Out Oil Demand Around the World". Bloomberg Green.

- ^ Takeo, Kumagai (2020). "Japan's May crude imports fall to 53-year low as COVID-19 cuts oil demand". S&P Global.

- ^ PAJ (2020). "Oil Statistics". Petroleum Association of Japan.

- ^ a b Energy Information Administration (2017). "Perspectives on the Development of LNG Market Hubs in the Asia Pacific Region" (PDF). US Energy Information Administration.

- ^ MJM Energy (2014). "East meets West - Japan Crude Cocktail and Henry Hub". MZINE.

- ^ Koyama, Ken (2015). "Time Lag between Crude Oil and LNG Price Movements" (PDF).