Jane Cobden

Jane Cobden | |

|---|---|

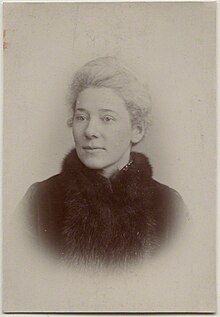

Portrait, 1890s | |

| Born | Emma Jane Catherine Cobden 28 April 1851 Westbourne Terrace, London, England |

| Died | 7 July 1947 (aged 96) Fernhurst, Surrey, England |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | |

| Father | Richard Cobden |

| Relatives | Anne Cobden-Sanderson (sister) |

Emma Jane Catherine Cobden (28 April 1851 – 7 July 1947) was a British Liberal politician who was active in many radical causes. A daughter of the Victorian reformer and statesman Richard Cobden, she was an early proponent of women's rights, and was one of two women elected to the inaugural London County Council in 1889. Her election was controversial; legal challenges to her eligibility hampered and eventually prevented her from serving as a councillor.

From her youth Jane Cobden, together with her sisters, sought to protect and develop the legacy of her father. She remained committed throughout her life to the "Cobdenite" issues of land reform, peace, and social justice, and was a consistent advocate for Irish independence from Britain. The battle for women's suffrage on equal terms with men, to which she made her first commitment in 1875, was her most enduring cause. Although she was sympathetic and supportive of those, including her sister Anne Cobden-Sanderson, who chose to campaign using militant, illegal methods, she kept her own activities within the law. She stayed in the Liberal Party, despite her profound disagreement with its stance on the suffrage issue.

After her marriage to the publisher Thomas Fisher Unwin in 1892, Jane Cobden extended her range of interests into the international field, in particular advancing the rights of the indigenous populations within colonial territories. As a convinced anti-imperialist she opposed the Boer War of 1899–1902, and after the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 she attacked its introduction of segregationist policies. In the years prior to World War I she opposed Joseph Chamberlain's tariff reform crusade on the grounds of her father's free trade principles, and was prominent in the Liberal Party's revival of the land reform issue. In the 1920s she largely retired from public life, and in 1928 presented the old Cobden family residence, Dunford House, to the Cobden Memorial Association as a conference and education centre dedicated to the issues and causes that had defined Cobdenism.

Early years

Family background and childhood

Jane Cobden was born on 28 April 1851 in Westbourne Terrace, London. She was the third daughter and fourth child of Richard Cobden,[1] who at the time of her birth was a Radical MP for the West Riding. With John Bright he had co-founded the Anti-Corn Law League which in the 1840s had spearheaded the successful campaign for the abolition of the Corn Laws.[2] Jane's mother was Catherine Anne, née Williams, the daughter of a timber merchant from Machynlleth in Wales; the older Cobden children were Richard ("Dick"), born 1841; Kate, born 1844; and Ellen, born 1848. Two further daughters followed Jane: Anne, born 1853, and Lucy, born 1861.[1]

In the 1830s, Richard had handed control of his prosperous calico-printing business to his brothers, so that he could concentrate on public service.[3] By 1849, the business was failing and Richard was close to financial ruin. He was saved from bankruptcy by a public subscription which not only settled his debts but also enabled him to acquire the farmhouse in which he had been born in 1804, at Dunford, near Heyshott in Sussex.[2][4] He rebuilt the property as a large villa, Dunford House, which became Jane Cobden's childhood home from the beginning of 1854.[5] In April 1856 Dick, who was at school at Weinheim in Germany, died there after a short illness.[6][n 1] The news was a devastating shock to the family,[7] and caused Richard's temporary withdrawal from public life. This hiatus was prolonged when, in 1857, he lost his parliamentary seat.[8] He returned to the House of Commons in May 1859, as Liberal MP for Rochdale.[9]

Because of his many absences from home, on parliamentary and other business, Richard Cobden was a somewhat remote figure to his daughters, although his letters indicate that he felt warmly towards them and that he wished to direct their political education. In later years they would all acknowledge his influence over their ideas. Both parents impressed on the girls their responsibilities for the poor in the local community; Jane Cobden's 1864 diary records visits to homes and workhouses. She and her younger sister Anne, at the ages of 12 and 10 respectively, taught classes in the local village school. The girls were encouraged by their father to contribute what money they possessed to relieve local poverty: "Do not keep the money ... as you have now made up your minds to give it to poor sufferers, let your own neighbours have it. Your Mama will tell you how to dispose of it, and tell me all about it".[10]

Sisterhood

Richard Cobden died after a severe bronchial attack on 2 April 1865, a few weeks before Jane's 14th birthday.[11] There followed a time of domestic uncertainty and financial worry, eventually resolved by a pension from the government of £1,500 a year, and the establishment of a "Cobden Tribute Fund" by his friends and followers.[12] After their father's death Jane and Anne attended Warrington Lodge school in Maida Hill but, following a disagreement the nature of which is unclear, both were removed from the school—"thrown on my hands", their mother complained.[13] In this difficult time, Catherine did not withdraw into seclusion; in 1866 she supervised the re-publication of her husband's Political Writings,[12] and in the same year became one of the 1,499 signatories to the "Ladies Petition", an event that the historian Sophia Van Wingerden marks as the beginning of the organised women's suffrage movement.[14]

"No more aimless wanderings abroad for me, I shall enter into the Women's Suffrage Campaign and so have a real interest in life".

In 1869 Dunford House was let. Catherine and her four younger daughters moved to a house in South Kensington—the eldest, Kate, had married in 1866. The ménage proved unsatisfactory; Ellen, Jane and Anne were now displaying considerable independence of spirit, and differences of opinion arose between mother and daughters. Catherine moved out, taking the youngest daughter Lucy, and went to Wales where she lived until her death in 1877.[15] In South Kensington, Ellen, Jane and Anne, often joined by Kate, established a sisterhood determined both to preserve Richard Cobden's memory and works and to uphold his principles and radical causes by actions of their own.[1] Together they stopped publication of a memoir of their father, sponsored by his former colleagues and compiled by a family friend, Julie Salis Schwabe. This caused some offence; Schwabe had given the family financial and emotional support after Richard's death.[16][n 2] However, Jane in particular wanted a more substantial memorial, and secured the services of John Morley, whose biography of Richard Cobden was published in 1881.[1][n 3]

During these years Jane often travelled abroad. In London, she and her sisters extended their range of acquaintances into literary and artistic circles; among their new friends were the writer George MacDonald and the Pre-Raphaelites William and Jane Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Ellen later married the painter Walter Sickert.[10] Jane developed an interest in the question of women's suffrage after attending a conference in London, in 1871.[18] In 1875 she made a specific commitment to this cause, although she did not become active in the movement for several years.[1] In the meantime, in 1879, she helped to found the Cobden Club in Heyshott, close to her father's birthplace.[10]

Early campaigns

Women's suffrage

From the late 1870s the Cobden sisters began to follow different pathways. Anne married Thomas Sanderson in 1882; inspired by her friendships within the Morris circle, her interests turned towards arts and crafts and eventually to socialism.[19] After her marriage to Sickert failed, Ellen became a novelist.[10] Jane became an active Liberal, on the radical wing of the party. In about 1879 she became a member of the National Society for Women's Suffrage, which had been founded in 1867 in the wake of the 1866 "Ladies Petition".[20] Jane joined the National Society's finance committee, and by 1880 was serving as its treasurer.[18] That year she was a speaker at a "Grand Demonstration" at St James's Hall, London, and in the following year addressed a similar meeting in Bradford.[18] In 1883 she attended a conference in Leeds, jointly organised by the National Liberal Federation and the National Reform Union, where she supported a motion proposed by Henry William Crosskey and seconded by Walter McLaren (John Bright's nephew), to extend the vote in parliamentary elections to certain women—those who, "possessing the qualifications that entitle men to vote, have now the right of voting in all matters of local government".[21]

The National Society's general stance was cautious; it avoided close identification with political parties, and for this reason would not accept affiliation from branches of the Women's Liberal Federation.[22] This, and its policy of excluding married women from any extension of the franchise, led to a split in 1888, with the formation of a breakaway "Central National Society" (CNS). Jane joined the executive committee of the new body, which encouraged the affiliation of Women's Liberal Associations and hoped that a future Liberal government would grant women's enfranchisement. However, the more radical members of the CNS felt that its commitment to votes for married women was too half-hearted.[23] In 1889 this group, which included Jane Cobden and Emmeline Pankhurst, formed the Women's Franchise League (WFL) with a specific policy of seeking votes for women on the same basis as for men, and the eligibility of women for all offices.[24]

Ireland

In 1848, Richard Cobden had written: "Almost every crime and outrage in Ireland is connected with the occupation or ownership of land ... if I had the power, I would always make the proprietors of the soil resident, by breaking up the large properties. In other words, I would give Ireland to the Irish".[25] Nevertheless, his views were held in the context of Unionism; he had condemned the 1848 "Young Ireland" rebellion as an act of insanity.[26] Jane adopted her father's standpoint on Irish land reform, yet embraced the cause of Irish home rule—on which she lectured regularly—and was a strong supporter of the Land League.[1] After visiting Ireland with the Women's Mission to Ireland in 1887, she subsequently used the pages of the English press to expose the mistreatment of evicted tenants. In a letter to The Times,[27] Jane and her associates cited one particular case—that of the Ryan family of Cloughbready in County Tipperary—to illustrate the British government's harshness towards even the most vulnerable of individuals. Jane sent money and food to alleviate the Ryan family's distress.[28]

Jane was in contact with Irish Land League leaders, including John Dillon and William O'Brien, and lobbied for the release of the latter after his imprisonment under the Protection of Person and Property Act 1881. She and her sisters supported the Irish Plan of Campaign, a scheme whereby tenants acted collectively to secure fair rents from their landlords. This plan was eventually denounced by the Roman Catholic Church as contrary to natural justice and Christian charity, although some priests supported it.[29][n 4] The attachment of Jane and her sisters to the rebellious factions in Ireland strained relations between the sisters and many of their father's former Liberal Unionist colleagues, but won approval from Thomas Bayley Potter, who had succeeded Richard Cobden as MP for Rochdale.[30] In October 1887 he wrote to Jane: "You are true to the living and just instincts of your father ... You know your father's heart better than John Bright does".[1]

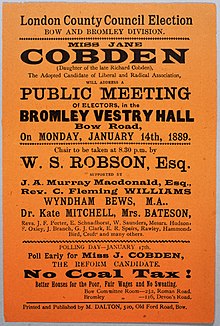

London County Council election 1889

Under the Municipal Corporations Act 1882 some women were qualified to vote in municipal elections, but were excluded from serving as councillors. However, the Local Government Act 1888, which created county councils, was interpreted by some as allowing women's election to these new bodies.[31] On 17 November 1888 a group of Liberal women decided to test the legal position. They formed the Society for Promoting the Return of Women as County Councillors (SPRWCC), established an election fund of £400 and selected two women—Jane Cobden and Margaret Sandhurst— as Liberal candidates for the newly created London County Council. Cobden was adopted by the party's Bow and Bromley division, and Sandhurst by Brixton.[32] Despite objections from the Conservatives, the women's nominations were accepted by the local returning officers.[33] Cobden's campaign in Bow and Bromley was organised with considerable enthusiasm and efficiency by the 29-year-old George Lansbury, then a Radical Liberal, later a socialist and eventually leader of the Labour Party.[34] Both Cobden and Sandhurst were victorious in the elections on 19 January 1889; they were joined by Emma Cons, whom the Progressive majority on the council selected to serve as an alderman.[35]

The women took their places on the inaugural council, and each accepted a range of committee assignments. Almost immediately, however, Sandhurst's defeated Conservative opponent, Beresford Hope, lodged a legal challenge against her election. When this was heard on 18 March, the judges ruled Sandhurst disqualified under the provisions of the 1882 Act. Her appeal was dismissed, and Beresford Hope was installed in her place. Cobden faced no such challenge, since her runner-up was a fellow-Liberal who had promised to support her.[35] Even so, her position on the council remained precarious, particularly after an attempt in parliament to legalise women's rights to serve as county councillors gained little support. A provision of the prevailing election law provided that anyone elected, even improperly, could not be challenged after twelve months, so on legal advice Cobden refrained from attending council or committee meetings until February 1890. When the statutory twelve months elapsed without challenge, she resumed her full range of duties.[36]

Although Cobden was now protected from challenge, the Conservative member for Westminster, Sir Walter De Souza, instituted fresh court proceedings against both Cobden and Cons. He argued that since they had been elected or selected unlawfully, their votes in the council had likewise been unlawful, making them liable to heavy financial penalties. In court the judge ruled against both women, though on appeal in April 1891 the penalties were reduced from an original £250 to a nominal £5. Cobden was urged by Lansbury and others not to pay even this token, but to go to prison; she declined this course of action. After a further parliamentary attempt to resolve the situation failed, she sat out the remaining months of her term as a councillor in silence, neither speaking nor voting, and did not seek re-election in the 1892 county elections.[36] Women did not receive the right to sit on county councils until 1907, with the passage of the Qualification of Women Act.[37][38][n 5]

In his account of the 1888–89 election, the historian Jonathan Schneer marks the campaign as a step in what he terms "working-class disenchantment with official Liberalism",[32] citing in particular Lansbury's departure from the Liberal Party in 1892. Schneer also remarks that this "pioneering political venture of British feminism ... provides at once an anticipation of, and a direct contrast to, the militant suffragism of the Edwardian era".[32][39]

Marriage, wider interests

In 1892, at the age of 41, Cobden married Thomas Fisher Unwin, an avant-garde publisher whose list included works by Henrik Ibsen, Friedrich Nietzsche, H. G. Wells and the young Somerset Maugham.[1] Unwin's involvement in a range of world and humanitarian causes led Cobden—who adopted the surname "Cobden Unwin"—to extend her interests to international peace and justice, reform in the Congo, and more generally the rights of aboriginal peoples.[1] She and Unwin opposed the Boer War (1899–1902); both were founder-members of the pro-Boer South African Conciliation Committee, Cobden acting as the committee's secretary.[28] The couple settled in South Kensington, from where Cobden continued to pursue her own causes. In 1893, with Laura Ormiston Chant, she represented the WFL in Chicago at the World Congress of Representative Women.[40] At home, she assisted women candidates in the 1894 Kensington "vestry" elections.[41] In 1900 she accepted the presidency of the Brighton Women's Liberal Association,[42] and in the same year wrote an extended tract, The Recent Development of Violence in our Midst, published by the Stop-the-War Committee.[43]

Edwardian campaigner

Votes for women, 1903–14

Although Cobden's views were more progressive than those of the Liberal Party's mainstream, she stayed a member of the party, believing that it remained the best political vehicle whereby her causes could be advanced. Other suffragists, including Anne Cobden Sanderson, took a different view, and aligned themselves with socialist movements.[44] When the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) began its militant campaign in 1905, Cobden refrained from participation in illegal actions, although she spoke out for her sister when Anne became one of the first suffragists to be sent to prison, after a demonstration outside Parliament in October 1906.[19] On Anne's release a month later, Cobden and her husband attended a celebration banquet at the Savoy Hotel, together with other WSPU prisoners. Cobden moved closer to the militant wing in 1907 when she endorsed the WSPU's new magazine, Votes for Women. That year she hosted an "At Home" meeting at which the WSPU leader Christabel Pankhurst was the principal speaker.[18] The WSPU was split when members who objected to the Pankhurst family's authoritarian leadership formed themselves into the Women's Freedom League;[45] Cobden did not join Anne in the breakaway movement, although she supported its associated body, the Women's Tax Resistance League.[18]

In 1911, Cobden was responsible for the Indian women's delegation in the Women's Coronation Procession, a London demonstration organised by suffrage associations from Britain and the Empire. The procession marched on 17 June 1911, a few days before King George V's coronation.[18][46] During 1910–12 several Conciliation Bills extending the parliamentary vote to a limited number of propertied women, were debated in the House of Commons. When the third of these was under discussion, Cobden sought the help of the Irish Parliamentary Party by reminding them of the support women had given to Ireland during the Land League agitation: "In the name of those 40,000 Englishwomen we urge you to support at every division this Bill by your presence and your vote".[28] The bill was finally abandoned when the Liberal prime minister, H. H. Asquith, replaced it with a bill extending the male suffrage.[47] In protest against the Liberal government's suffrage policies and its harsh treatment of militants, Cobden resigned her honorary presidency of the Women's Liberal Association in Rochdale, her father's last constituency.[18]

Social, political and humanitarian activities

Although the cause of women's suffrage remained her principal concern, at least until the First World War, Cobden was active in other campaigns. In 1903 she defended the principles of free trade, as expressed by her father, against Joseph Chamberlain's tariff reform crusade. Chamberlain had called for a policy of Imperial Preference, and the imposition of tariffs against countries opposed to Britain's imperial interests.[48] To a meeting in Manchester, Cobden expressed confidence that "Manchester ... will tell Mr Chamberlain that it is still loyal to our old flag: free trade, peace and goodwill among nations".[49] In 1904, Richard Cobden's centenary year, she published The Hungry Forties, described by Anthony Howe in a biographical article as "an evocative and brilliantly successful tract". It was one of several free trade books and pamphlets issued by the Fisher Unwin press which, together with celebratory centenary events, helped to define free trade as a major progressive cause of the Edwardian era.[1]

The Cobdenite cause of land reform was revived in the 1900s as a major Liberal policy,[50] helped in 1913 by the publication of Jane Cobden's book The Land Hunger: Life under Monopoly. The dedication read: "To the memory of Richard Cobden who loved his native land, these pages are dedicated by his daughter, in the hope that his desire—'Free Trade in Land'—may be fulfilled".[16] Cobden did not confine her interests to domestic affairs. From 1906, along with Helen Bright Clark, she was an active member of the Aborigines' Protection Society,[51] an organisation concerned with the rights of indigenous peoples under colonial rule; the society merged with the Anti-Slavery Society in 1909.[52] In 1907 she lobbied the prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, on behalf of the Friends of Russian Freedom, seeking his support for amendments to the Hague Convention, then in session in Geneva[28] Her efforts for the poorest in society encompassed appeals on behalf of the families of striking workers in London and Dublin during the labour unrest of 1913–14, and of starving women and children in Tripoli.[1] She also found time to act as secretary to the memorial fund for Emma Cons, after the latter's death in 1912.[n 6]

Late campaigns

During the war years 1914–18, with the issue of women's suffrage quiescent,[n 7] Cobden became increasingly involved in South African affairs. She supported Solomon Plaatje's campaign against the segregationist Natives' Land Act of 1913, a stance that led, in 1917, to her removal from the committee of the Anti-Slavery Society. The Society's line was to support the Botha government's land reform policy; Cobden denounced Sir John Harris, the Society's parliamentary representative, for being a false friend to the native people by secretly working against them.[28] Cobden maintained her commitment to the cause of Irish independence, and offered personal help to victims of the Black and Tans during the Irish War of Independence, 1919–21.[1]

In 1920, Cobden gave Dunford House to the London School of Economics (LSE), of which she had become a governor. According to Beatrice Webb, co-founder of the School, she soon regretted the gift; Webb wrote in her diary on 2 May 1923: "The poor lady ... makes fretful complaints if a single bush is cut down or a stone shifted, whilst she vehemently resents the high spirits of the students ... not to mention the opinions of some of the lecturers".[56] Later in 1923, LSE returned the house to Cobden; in 1928 she donated it to the Cobden Memorial Association. With the help of the writer and journalist Francis Wrigley Hirst and others, the house became a conference and education centre for pursuing the traditional Cobdenite causes of free trade, peace and goodwill.[57]

Final years, death and legacy

After 1928, Jane Cobden's chief occupation was the organisation of her father's papers, some of which she placed in the British Museum.[1] Others were eventually collected, with other Cobden family documents, by the West Sussex County Council Record Office at Chichester.[2] In old age she lived quietly at Oatscroft, her home near Dunford House, and following her husband's death in 1935 made few interventions in public life.[1] During the 1930s, under Hirst's direction, Dunford House continued to preach what Howe describes as "the pure milk of the Cobdenian faith": the conviction that in Britain and in continental Europe, peace and prosperity would develop from individual ownership of the soil.[58] Jane Cobden died, aged 96, on 7 July 1947, at Whitehanger Nursing Home in Fernhurst, Surrey.[1] In the years following her death her papers were collected and deposited as part of the family archive in Chichester.[2] In 1952 Dunford House was transferred to the YMCA, although its general educational functions and mission remained unchanged. The house contains numerous memorabilia of the Cobden family.[57]

Howe depicts Jane Cobden as a formidable personality, known by her husband's publishing colleagues as "The Jane", who took a keen and even intrusive interest in the work of the publishing house. She was, Howe says, "a woman of sentiment and enthusiasm who took up (and sometimes speedily dropped) causes with a fire which brooked no opposition".[1] In an essay on the Cobden sisterhood, the feminist historian Sarah Richardson remarks on the different paths chosen by the sisters by which to take their father's legacy forward: "Jane's activities showed that it was still possible to follow a radical agenda within the aegis of Liberalism". Richardson indicates that the main collective achievement of Jane and her sisters was to ensure that the Cobden name, with its radical and progressive associations, survived well into the 20th century. "In doing so", Richardson concludes, "they proved themselves worthy successors to their father, guaranteeing that his contribution was not only sustained, but remodelled for a new age".[59]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Morley's biography of Richard Cobden records Dick's death, but does not name him. The book makes no references to any of the Cobden daughters.[7]

- ^ A French version of Schwabe's book was published in Paris; the English version was delayed until 1895, when it was published by Thomas Fisher Unwin, who had by then become Jane's husband.[16]

- ^ Morley had never met Richard Cobden, but was given full access to the family's papers. Morley's own biographer, Richard Jackson, describes the Cobden book as "overlong" and uncritical, though "an unpretentious and attractive personality emerges clearly".[17]

- ^ According to the historian Michael J. F. O'Donnell, the principles of the Plan of Campaign were: "The tenants of a locality were to form themselves into an association, each member of which was to proffer to the landlord or his agent a sum which was estimated by the general body as a fair rent for his holding. These sums, if refused by the landlord, were pooled and divided by the association for the maintenance of those tenants who were evicted".[29]

- ^ In 1889 Jane Cobden's portrait was painted by her friend Emily Osborn, with whom she was then sharing a house. The portrait was exhibited at the Society of Lady Artists in 1891, and was later installed in the council chamber of the London County Council (LCC). In 1989 it was cut from its frame and stolen, after the abolition of the LCC's successor body, the Greater London Council.[18]

- ^ The funds eventually went to the Old Vic theatre, which Cons's niece Lilian Baylis developed from the "Royal Victoria Coffee Music Hall" established by Cons in 1880.[53]

- ^ The women's suffrage campaigns were suspended on the outbreak of war in 1914. Younger women volunteered in large numbers to help the war effort; in July 1915 Christabel Pankhurst led a "right to serve" march down Whitehall. Partly in recognition of women's contributions, the Representation of the People Act 1918 extended the parliamentary franchise to women over 30, subject to a property qualification.[54][55]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Howe, Anthony (May 2006). "Unwin, (Emma) Jane Catherine Cobden". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38683. Retrieved 16 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Miles (May 2009). "Cobden, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5741. Retrieved 16 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Morley, pp. 117–18

- ^ "The Cobden Archives". West Sussex County Council. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Rogers, pp. 84–91

- ^ Rogers, pp. 115–16

- ^ a b Morley, pp. 645–50 and pp. 965–72

- ^ Morley, p. 657

- ^ Morley, p. 689

- ^ a b c d Richardson, pp. 235–36

- ^ Rogers, pp. 175–76

- ^ a b Rogers, p. 178

- ^ Rogers, p. 179

- ^ Van Wingerden, pp. 1–2

- ^ Rogers, pp. 180–81

- ^ a b c Richardson, p. 231

- ^ Jackson, p. 76

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crawford, pp. 694–96

- ^ a b Howe, Anthony (January 2004). "Sanderson, (Julia Sarah) Anne Cobden". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56224. Retrieved 17 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Rosen, pp. 6–7

- ^ Crawford, p. 154

- ^ Howarth, Janet (October 2007). "Fawcett, Dame Millicent Garrett". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33096. Retrieved 17 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Crawford, pp. 103–04

- ^ Rosen, p. 17

- ^ Letter 28 October 1848, quoted in Morley, p. 493

- ^ Letter 21 July 1848, quoted in Morley, p. 488

- ^ Rowntree, Isabella, Sickert, Ellen and Cobden, Jane (27 October 1887). "The Administration of the Law in Ireland". The Times. p. 6.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Richardson, pp. 238–39

- ^ a b O'Donnell, pp. 103–04

- ^ Howe, Anthony (January 2008). "Potter, Thomas Bayley". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22621. Retrieved 18 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Hollis, pp. 306–07

- ^ a b c Schneer, Jonathan (January 1991). "Politics and Feminism in 'Outcast London': George Lansbury and Jane Cobden's Campaign for the First London County Council". Journal of British Studies. 30 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1086/385973. JSTOR 175737. S2CID 155015712. (subscription required)

- ^ Hollis, p. 309

- ^ Shepherd, pp. 21–23

- ^ a b Hollis, pp. 310–11

- ^ a b Hollis, pp. 311–15

- ^ Hollis, p. 392

- ^ Wilson, p. 48

- ^ Shepherd, p. 24

- ^ Crawford, p. 105

- ^ Hollis, p. 343

- ^ Crawford, p. 293

- ^ The recent development of violence in our midst. London: Stop-the-War Committee. 1900. OCLC 25172346.

- ^ Richardson, p. 242

- ^ Pugh, p. 144 and pp. 163–67

- ^ "Indian suffragettes in the Women's Coronation Procession". Museum of London. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Britain 1906–18: Gaining Women's Suffrage". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Marsh, Peter T (January 2011). "Chamberlain, Joseph (Joe)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32350. Retrieved 5 April 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Richardson, p. 232

- ^ Baines, Malcolm (September 1996). "God Gave the Land to the People" (PDF). Liberal Democrat History Group Newsletter (12): 11. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ Crawford, p. 114

- ^ "Papers of the Anti-Slavery Society: Organizational history". Bodleian Library of Commonwealth & African Studies. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "The Royal Victoria Hall – "The Old Vic"". University of London & History of Parliament Trust. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Taylor A.J.P., p. 68 and pp. 133–34

- ^ "Representation of the People Act, 1918" (PDF). Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "Beatrice Webb's typescript diary: entry 2 May 1923". LSE Digital Library. p. 426. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Cobden Country" (PDF). The Midhurst Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Howe, Anthony (May 2006). "Hirst, Francis Wrigley". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33891. Retrieved 27 March 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Richardson, p. 246

Sources

- Crawford, Elizabeth (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866–1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 0-415-23926-5.

- Hollis, Patricia (1987). Ladies Elect: Women in English Local Government 1865–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822699-3.

- Jackson, Patrick (2012). Morley of Blackburn: A Literary and Political Biography of John Morley. Plymouth: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1-61147-534-0.

- Morley, John (1903). The Life of Richard Cobden. London: T. Fisher Unwin. OCLC 67567974. (First published by Chapman and Hall, London 1881)

- O'Donnell, Michael (1908). Ireland and the Home Rule movement. Dublin: Maunsel & Co. OCLC 2282481.

- Pugh, Martin (2008). The Pankhursts. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-952043-6.

- Richardson, Sarah, in Howe, Anthony and Morgan, Simon (eds): Nineteenth Century Liberalism: Richard Cobden bicentenary essays (2006). You Know Your Father's Heart: The Cobden Sisterhood and the Legacy of Richard Cobden. Aldershot, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5572-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rogers, Jean Scott (1990). Cobden and his Kate: The story of a marriage. London: Historical Publications. ISBN 0-948667-11-7.

- Rosen, Andrew (1974). Rise Up, Women!. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7934-6.

- Shepherd, John (2002). George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820164-8.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1970). English History 1914–45. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-021181-0.

- Van Wingerden, Sophia A. (1999). The Women's Suffrage in Britain, 1866–1928. Basingstoke, UK and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-66911-8.

- Wilson, A.N. (2006). After the Victorians. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-945187-7.