Józef Piłsudski

Józef Piłsudski | |

|---|---|

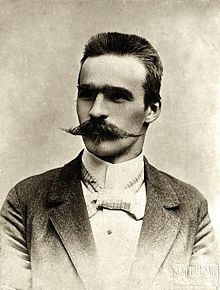

Piłsudski c. 1920s | |

| Chief of State of Poland | |

| In office 22 November 1918 – 14 December 1922 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Regency Council |

| Succeeded by | Gabriel Narutowicz (as President) |

| Prime Minister of Poland | |

| In office 2 October 1926 – 27 June 1928 | |

| President | Ignacy Mościcki |

| Deputy | Kazimierz Bartel |

| Preceded by | Kazimierz Bartel |

| Succeeded by | Kazimierz Bartel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Józef Klemens Piłsudski 5 December 1867 Zułów, Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania) |

| Died | 12 May 1935 (aged 67) Warsaw, Poland |

| Political party | Independent |

| Other political affiliations | Polish Socialist Party (1893–1918)[c] |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Marshal of Poland |

| Battles/wars | |

Józef Klemens Piłsudski[a] (Polish: [ˈjuzɛf ˈklɛmɛns piwˈsutskʲi] ⓘ; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he became an increasingly dominant figure in Polish politics and exerted significant influence on shaping the country's foreign policy. Piłsudski is viewed as a father of the Second Polish Republic, which was re-established in 1918, 123 years after the final partition of Poland in 1795, and was considered de facto leader (1926–1935) of the Second Republic as the Minister of Military Affairs.

Seeing himself as a descendant of the culture and traditions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Piłsudski believed in a multi-ethnic Poland—"a home of nations" including indigenous ethnic and religious minorities. Early in his political career, Piłsudski became a leader of the Polish Socialist Party. Believing Poland's independence would be won militarily, he formed the Polish Legions. In 1914, he predicted a new major war would defeat the Russian Empire and the Central Powers. After World War I began in 1914, Piłsudski's Legions fought alongside Austria-Hungary against Russia. In 1917, with Russia faring poorly in the war, he withdrew his support for the Central Powers, and was imprisoned in Magdeburg by the Germans.

Piłsudski was Poland's Chief of State from November 1918, when Poland regained its independence, until 1922. From 1919 to 1921 he commanded Polish forces in six wars that re-defined the country's borders. On the verge of defeat in the Polish–Soviet War in August 1920, his forces repelled the invading Soviet Russians at the Battle of Warsaw. In 1923, with a government dominated by his opponents, in particular the National Democrats, Piłsudski retired from active politics. Three years later he returned to power in the May Coup and became the strongman of the Sanation government.[1][2][3] He focused on military and foreign affairs until his death in 1935, developing a cult of personality that has survived into the 21st century.

Although some aspects of Piłsudski's administration, such as imprisoning his political opponents at Bereza Kartuska, are controversial, he remains one of the most influential figures in Polish 20th-century history and is widely regarded as a founder of modern Poland.

Early life

Piłsudski was born 5 December 1867 to the noble Piłsudski family at their manor of Zułów near the village of Zułów (now Zalavas in Lithuania).[4][5] At his birth, the village was part of the Russian Empire and had been so since 1795. Before that, it was in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, an integral part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1795. After World War I, the village was part of the Vilnius Region that was contested between Lithuania and Poland throughout the interwar period. From 1922 until 1939, the village was in the Second Polish Republic. During World War II, the village suffered Soviet and German occupations. The estate was part of the dowry brought by his mother, Maria, a member of the wealthy Billewicz family.[6] The Piłsudski family, although pauperized,[7] cherished Polish patriotic traditions,[8][9] and are characterized either as Polish[10][11] or as Polonized Lithuanians.[7][12][b] Józef was the second son born to the family.[13]

Józef was not an especially diligent student when he attended the Russian Gymnasium in Vilnius.[14] Along with his brothers Bronisław, Adam and Jan, Józef was introduced by his mother Maria to Polish history and literature, which were suppressed by the Imperial authorities.[15] His father, also named Józef, fought in the January 1863 Uprising against Russian rule.[8] The family resented the government's Russification policies. Young Józef profoundly disliked having to attend Russian Orthodox Church services [15] and left school with an aversion for the Russian Tsar, its empire, and its culture.[7]

In 1885 Piłsudski started medical studies at Kharkov University where he became involved with Narodnaya Volya, part of the Russian Narodniks revolutionary movement.[16] In 1886, he was suspended for participating in student demonstrations.[8] He was rejected by the University of Dorpat, whose authorities had been informed of his political affiliation.[8] On 22 March 1887, he was arrested by Tsarist authorities on a charge of plotting with Vilnius socialists to assassinate Tsar Alexander III; Piłsudski's main connection to the plot was the involvement of his brother Bronisław.[17][18] Józef was sentenced to five years' exile in Siberia, first at Kirensk on the Lena River, then at Tunka.[8][18]

Siberian exile

While being transported in a prisoners' convoy to Siberia, Piłsudski was held for several weeks at a prison in Irkutsk.[19] During his stay, another inmate insulted a guard and refused to apologize; Piłsudski and other political prisoners were beaten by the guards for their defiance and Piłsudski lost two teeth. He took part in a subsequent hunger strike until the authorities reinstated political prisoners' privileges that had been suspended after the incident.[20] For his involvement, he was sentenced in 1888 to six months' imprisonment. He had to spend the first night of his incarceration in 40-degree-below-zero Siberian cold; this led to an illness that nearly killed him and health problems that would plague him throughout life.[21]

During his exile, Piłsudski met many Sybiraks, groups of people who have resettled to Siberia.[22] He was allowed to work in an occupation of his choosing and tutored local children in mathematics and foreign languages[7] (he knew French, German and Lithuanian in addition to Russian and his native Polish; he would later learn English).[23] Local officials decided that, as a Polish noble, he was not entitled to the 10-ruble pension received by others.[24]

Polish Socialist Party

In 1892 Piłsudski returned from exile and settled in Adomavas Manor near Teneniai. In 1893, he joined the Polish Socialist Party (PPS)[8], and helped organize their Lithuanian branch.[25] Initially, he sided with the Socialists' more radical wing, but despite the socialist movement's ostensible internationalism, he remained a Polish nationalist.[26] In 1894, as its chief editor, he published an underground socialist newspaper called Robotnik (The Worker); he would also be one of its chief writers and a typesetter.[8][16][27][28] In 1895, he became a PPS leader, promoting the position that doctrinal issues were of minor importance and socialist ideology should be merged with nationalist ideology because this combination offered the greatest chance of restoring Polish independence.[16]

On 15 July 1899, while an underground organizer, Piłsudski married a fellow socialist organizer, Maria Juszkiewiczowa, née Koplewska.[29][30][31] According to his biographer Wacław Jędrzejewicz, the marriage was less romantic than pragmatic. Robotnik's printing press was housed in their apartment first in Vilnius, then in Łódź. A pretext of regular family life made them less suspect. Also, Russian law protected a wife from prosecution for the illegal activities of her husband.[32] The marriage deteriorated when, several years later, Piłsudski began an affair with a younger socialist,[26] Aleksandra Szczerbińska. Maria died in 1921; in October that year, Piłsudski married Aleksandra. By then, the couple had two daughters, Wanda and Jadwiga.[33]

In February 1900 Piłsudski was imprisoned at the Warsaw Citadel when Russian authorities found Robotnik's underground printing press in Łódź. He feigned mental illness in May 1901 and escaped from a mental hospital at Saint Petersburg with the help of a Polish physician, Władysław Mazurkiewicz, and others. He fled to Galicia, then part of Austria-Hungary, and thence to Leytonstone in London, staying with Leon Wasilewski and his family.[8]

Armed resistance

In the early 1900s, almost all parties in Russian Poland and Lithuania took a conciliatory position toward the Russian Empire and aimed at negotiating within it a limited autonomy for Poland. Piłsudski's PPS was the only political force prepared to fight the Empire for Polish independence and to resort to violence to achieve that goal.[7]

On the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in the summer of 1904, Piłsudski traveled to Tokyo, Japan, where he tried unsuccessfully to obtain that country's assistance for an uprising in Poland. He offered to supply Japan with intelligence to support its war with Russia, and proposed the creation of a Polish Legion from Poles,[34] conscripted into the Russian Army, who had been captured by Japan. He also suggested a "Promethean" project directed at breaking up the Russian Empire, a goal that he later continued to pursue.[35] Meeting with Yamagata Aritomo, he suggested that starting a guerrilla war in Poland would distract Russia and asked for Japan to supply him with weapons. Although the Japanese diplomat Hayashi Tadasu supported the plan, the Japanese government, including Yamagata, was more skeptical.[36] Piłsudski's arch-rival, Roman Dmowski, travelled to Japan and argued against Piłsudski's plan, discouraging the Japanese government from supporting a Polish revolution because he thought it was doomed to fail.[34][37] The Japanese offered Piłsudski much less than he hoped; he received Japan's help in purchasing weapons and ammunition for the PPS and their combat organisation, and the Japanese declined the Legion proposal.[8][34]

In the fall of 1904, Piłsudski formed a paramilitary unit (the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party, or bojówki) aiming to create an armed resistance movement against the Russian authorities.[37] The PPS organized demonstrations, mainly in Warsaw. On 28 October 1904, Russian Cossack cavalry attacked a demonstration, and in reprisal, during a demonstration on 13 November, Piłsudski's paramilitary opened fire on Russian police and military.[37][38] Initially concentrating their attention on spies and informers, in March 1905, the paramilitary began using bombs to assassinate selected Russian police officers.[39]

Russian Revolution of 1905

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Piłsudski played a leading role in events in Congress Poland. In early 1905 he ordered the PPS to launch a general strike there; it involved some 400,000 workers and lasted two months until it was broken by the Russian authorities.[37] In June 1905, Piłsudski sent paramilitary aid to an uprising in Łódź, later called June Days. In Łódź, armed clashes broke out between Piłsudski's paramilitaries and gunmen loyal to Dmowski and his National Democrats.[37] On 22 December 1905, Piłsudski called for all Polish workers to rise up; the call went largely unheeded.[37]

Piłsudski instructed the PPS to boycott the elections to the First Duma.[37] The decision, and his resolve to try to win Polish independence through revolution, caused tensions within the PPS, and in November 1906, the party fractured over Piłsudski's leadership.[40] His faction came to be called the "Old Faction" or "Revolutionary Faction" ("Starzy" or "Frakcja Rewolucyjna"), while their opponents were known as the "Young Faction", "Moderate Faction" or "Left" ("Młodzi", "Frakcja Umiarkowana", "Lewica"). The "Young" sympathized with the Social Democrats of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania, and believed priority should be given to co-operation with Russian revolutionaries in toppling the Russian Empire and creating a socialist utopia to facilitate negotiations for independence.[16] Piłsudski and his supporters in the Revolutionary Faction continued to plot a revolution against Tsarist Russia to secure Polish independence.[8] By 1909, his faction was the majority in the PPS, and Piłsudski remained an important PPS leader until the outbreak of the First World War.[41]

Prelude to World War I

Piłsudski anticipated a coming European war[42] and the need to organize the leadership of a future Polish army. He wanted to secure Poland's independence from the three empires that partitioned Poland out of political existence in the late 18th century. In 1906 Piłsudski, with the connivance of the Austrian authorities, founded a military school in Kraków for the training of paramilitary units.[40] In 1906 alone, the 800-strong paramilitaries, operating in five-man teams in Congress Poland, killed 336 Russian officials; in subsequent years, the number of their casualties declined, and the paramilitaries' numbers increased to some 2,000 in 1908.[40][43] The paramilitaries also held up Russian currency transports that were leaving Polish territories. On the night of 26/27 September 1908, they robbed a Russian mail train that was carrying tax revenues from Warsaw to Saint Petersburg.[40] Piłsudski, who took part in this Bezdany raid near Vilnius, used the funds so obtained to finance his secret military organization.[44] The funds totaled 200,812 rubles which was a fortune for the time and equaled the paramilitaries' entire income for the two preceding years.[43]

In 1908, Piłsudski transformed his paramilitary units into a "Union of Active Struggle" (Związek Walki Czynnej, or ZWC), headed by three of his associates, Władysław Sikorski, Marian Kukiel and Kazimierz Sosnkowski.[40] The ZWC's main purpose was to train officers and noncommissioned officers for a future Polish Army.[16] In 1910, two legal paramilitary organizations were created in the Austrian zone of Poland, one in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), and one in Kraków, to conduct training in military science. With the permission of the Austrian officials, Piłsudski founded a series of "sporting clubs", then the Riflemen's Association, as cover for the training of a Polish military force. In 1912, Piłsudski (using the pseudonym "Mieczysław") became commander-in-chief of a Riflemen's Association (Związek Strzelecki). By 1914, they had increased to 12,000 men.[8][40] In 1914, while giving a lecture in Paris, Piłsudski declared, "Only the sword now carries any weight in the balance for the destiny of a nation", arguing that Polish independence can only be achieved through military struggle against the partitioning powers.[40][45]

World War I

At a meeting in Paris in 1914, Piłsudski presciently declared that for Poland to regain independence in the impending war, Russia must be beaten by the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires) and the latter powers must in turn be beaten by France, Britain, and the United States.[42][46]

At the outbreak of war, on 3 August in Kraków Piłsudski formed a small cadre military unit called the First Cadre Company from members of the Riflemen's Association and Polish Rifle Squads.[47] That same day, a cavalry unit under Władysław Belina-Prażmowski was sent to reconnoitre across the Russian border before the official declaration of war between Austria-Hungary and Russia on 6 August 1914.[48]

Piłsudski's strategy was to send his forces north across the border into Russian Poland into an area the Russian Army had evacuated in the hope of breaking through to Warsaw and sparking a nationwide revolution.[16][49] Using his limited forces in those early days, he backed his orders with the sanction of a fictitious "National Government in Warsaw",[50] and he bent and stretched Austrian orders to the utmost, taking initiatives, moving forward, and establishing Polish institutions in liberated towns, whereas the Austrians saw his forces as good only for scouting or for supporting main Austrian formations.[51] On 12 August 1914 Piłsudski's forces took the town of Kielce, in Kielce Governorate, but Piłsudski found the residents less supportive than he had expected.[52]

On 27 August 1914 Piłsudski established the Polish Legions, formed within the Austro-Hungarian Army,[53] and took personal command of their First Brigade,[8] which he would lead into several victorious battles.[16] He also secretly informed the British government in the fall of 1914 that his Legions would never fight against France or Britain, only Russia.[49]

Piłsudski decreed that Legions' personnel were to be addressed by the French Revolution-inspired "Citizen" (Obywatel), and he was referred to as "the Commandant" ("Komendant").[54] Piłsudski enjoyed extreme respect and loyalty from his men, which would remain for years to come.[54] The Polish Legions fought against Russia, at the side of the Central Powers, until 1917.[55]

In August 1914 Piłsudski had set up the Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa), which served as a precursor of the Polish intelligence agency and was designed to perform espionage and sabotage missions.[16][49][56]

In mid-1916, after the Battle of Kostiuchnówka, in which the Polish Legions delayed a Russian offensive at a cost of over 2,000 casualties,[57] Piłsudski demanded that the Central Powers issue a guarantee of independence for Poland. He supported that demand with his own proffered resignation and that of many of the Legions' officers.[58] On 5 November 1916 the Central Powers proclaimed the independence of Poland, hoping to increase the number of Polish troops that could be sent to the Eastern Front against Russia, thereby relieving German forces to bolster the Western Front.[44][59]

Piłsudski agreed to serve in the Regency Kingdom of Poland, created by the Central Powers, and acted as minister of war in the newly formed Polish Regency government; as such, he was responsible for the Polnische Wehrmacht.[54] After the Russian Revolution in early 1917, and in view of the worsening situation of the Central Powers, Piłsudski took an increasingly uncompromising stance by insisting that his men no longer be treated as "German colonial troops" and be only used to fight Russia. Anticipating the Central Powers' defeat in the war, he did not wish to be allied with the losing side.[60][61]

In the aftermath of the July 1917 "oath crisis", when Piłsudski forbade Polish soldiers to swear loyalty to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, he was arrested and imprisoned at Magdeburg.[62] The Polish units were disbanded and the men were incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Army,[8][49] while the Polish Military Organization began attacking German targets.[16] Piłsudski's arrest greatly enhanced his reputation among Poles, many of whom began to see him as a leader willing to take on all the partitioning powers.[16]

On 8 November 1918, three days before the Armistice, Piłsudski and his colleague, Colonel Kazimierz Sosnkowski, were released by the Germans from Magdeburg and soon placed on a train bound for the Polish capital, Warsaw – the collapsing Germans hoping that Piłsudski would create a force friendly to them.[49]

Rebuilding Poland

Head of state

On 11 November 1918, Piłsudski was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Polish forces by the Regency Council and was entrusted with creating a national government for the newly independent country. Later that day, which would become Poland's Independence Day, he proclaimed an independent Polish state.[49] That week, Piłsudski negotiated the evacuation of the German garrison from Warsaw and of other German troops from Ober Ost. Over 55,000 Germans peacefully departed Poland, leaving their weapons to the Poles. In the coming months, over 400,000 in total departed over Polish territories.[49][63]

On 14 November 1918, Piłsudski was asked to supervise provisionally the running of the country. On 22 November he officially received, from the new government of Jędrzej Moraczewski, the title of Provisional Chief of State (Tymczasowy Naczelnik Państwa) of renascent Poland.[8] Various Polish military organizations and provisional governments (the Regency Council in Warsaw; Ignacy Daszyński's government in Lublin; and the Polish Liquidation Committee in Kraków) supported Piłsudski. He established a coalition government that was predominantly socialist and introduced many reforms long proclaimed as necessary by the Polish Socialist Party, such as the eight-hour day, free school education and women's suffrage, to avoid major unrest. As head of state, Piłsudski believed he must remain separated from partisan politics.[16][49]

The day after his arrival in Warsaw, he met with old colleagues from his time working with the underground resistance, who addressed him socialist-style as "Comrade" (Towarzysz) and asked for his support for their revolutionary policies. He refused it and supposedly answered:

"Comrades, I took the red tram of socialism to the stop called Independence, and that's where I got off. You may keep on to the final stop if you wish, but from now on let's address each other as 'Mister' [rather than continue using the socialist term of address, 'Comrade']!"[8]

However, the authenticity of this quote is disputed.[64][65] Piłsudski declined to support any party and did not form any political organization of his own; instead, he advocated creating a coalition government.[16][66]

First policies

Piłsudski set about organizing a Polish army out of Polish veterans of the German, Russian, and Austrian armies. Much of former Russian Poland had been destroyed in the war, and systematic looting by the Germans had reduced the region's wealth by at least 10%.[67] A British diplomat who visited Warsaw in January 1919 reported: "I have nowhere seen anything like the evidence of extreme poverty and wretchedness that meet one's eye at almost every turn."[67] In addition, the country had to unify the disparate systems of law, economics, and administration in the former German, Austrian, and Russian sectors of Poland. There were nine legal systems, five currencies, and 66 types of rail systems (with 165 models of locomotives), each needing to be consolidated.[67]

Biographer Wacław Jędrzejewicz described Piłsudski as very deliberate in his decision-making: Piłsudski collected all available pertinent information, then took his time weighing it before arriving at a final decision. He held long working hours, and maintained a simple lifestyle, eating plain meals alone at an inexpensive restaurant.[67] Though he was popular with much of the Polish public, his reputation as a loner (the result of many years' underground work) and as a man who distrusted almost everyone led to strained relations with other Polish politicians.[26]

Piłsudski and the first Polish government were distrusted in the West because he had co-operated with the Central Powers from 1914 to 1917 and because the governments of Daszyński and Moraczewski were primarily socialist.[49] It was not until January 1919, when pianist and composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski became Prime Minister of Poland and foreign minister of a new government, that Poland was recognized in the West.[49] Two separate governments were claiming to be Poland's legitimate government: Piłsudski's in Warsaw and Dmowski's in Paris.[67] To ensure that Poland had a single government and to avert civil war, Paderewski met with Dmowski and Piłsudski and persuaded them to join forces, with Piłsudski acting as Provisional Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief, while Dmowski and Paderewski represented Poland at the Paris Peace Conference.[68] Articles 87–93 of the Treaty of Versailles[69] and the Little Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, formally established Poland as an independent and sovereign state in the international arena.[70]

Piłsudski often clashed with Dmowski for viewing the Poles as the dominant nationality in renascent Poland, and attempting to send the Blue Army to Poland through Danzig, Germany (now Gdańsk, Poland).[71][72] On 5 January 1919, some of Dmowski's supporters (Marian Januszajtis-Żegota and Eustachy Sapieha) attempted a coup against Piłsudski but failed.[73] On 20 February 1919, Polish parliament (the Sejm) confirmed his office when it passed the Little Constitution of 1919, although Piłsudski proclaimed his intention to eventually relinquish his powers to the parliament. "Provisional" was struck from his title, and Piłsudski held the office of the Chief of State until 9 December 1922, after Gabriel Narutowicz was elected as the first president of Poland.[8]

Piłsudski's major foreign policy initiative was a proposed federation (to be called "Międzymorze" (Polish for "Between-Seas"), and known from the Latin as Intermarium, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. In addition to Poland and Lithuania, it was to consist of Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia and Estonia,[49] somewhat in emulation of the pre-partition Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[16][74] Piłsudski's plan met with opposition from most of the prospective member states, which refused to relinquish their independence, as well as the Allied powers, who thought it to be too bold a change to the existing balance-of-power structure.[75] According to historian George Sanford, it was around 1920 that Piłsudski came to realize the infeasibility of that version of his Intermarium project.[76] Instead of a Central and Eastern European alliance, there soon appeared a series of border conflicts, including the Polish–Ukrainian War (1918–19), the Polish–Lithuanian War (1919–1920, culminating in Żeligowski's Mutiny), Polish–Czechoslovak border conflicts (beginning in 1918), and most notably the Polish–Soviet War (1919–21).[16] Winston Churchill commented, "The war of giants has ended; the wars of the pygmies have begun."[77]

Polish–Soviet War

In the aftermath of World War I, there was unrest on all Polish borders. Regarding Poland's future frontiers, Piłsudski said: "All that we can gain in the west depends on the Entente—on the extent to which it may wish to squeeze Germany." The situation was different in the east, of which Piłsudski said that "there are doors that open and close, and it depends on who forces them open and how far."[78] In the east, Polish forces clashed with Ukrainian forces in the Polish–Ukrainian War, and Piłsudski's first orders as Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army, on 12 November 1918, were to provide support for the Polish struggle in Lviv.[79]

Piłsudski was aware that the Bolsheviks would not ally with an independent Poland and predicted that war with them was inevitable.[80] He viewed their advance west as a major problem, but he also considered the Bolsheviks less dangerous for Poland than their White opponents.[81] The "White Russians", representatives of the old Russian Empire, were willing to accept limited independence for Poland, probably within borders similar to those of the former Congress Poland. They objected to Polish control of Ukraine, which was crucial for Piłsudski's Intermarium project.[82] This contrasted with the Bolsheviks, who proclaimed the partitions of Poland null and void.[83] Piłsudski speculated that Poland would be better off with the Bolsheviks, alienated from the Western powers, than with a restored Russian Empire.[81][84] By ignoring the strong pressures from the Entente Cordiale to join the attack on Lenin's struggling Bolshevik government, Piłsudski probably saved it in the summer and the fall of 1919.[85]

After the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919, and a series of escalating battles that resulted in the Poles advancing eastward, on 21 April 1920, Marshal Piłsudski (as his rank had been since March 1920) signed a military alliance called the Treaty of Warsaw with Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura. The treaty allowed both countries to conduct joint operations against Soviet Russia. The goal of the Polish-Ukrainian Treaty was to establish an independent Ukraine and independent Poland in alliance, resembling that once existing within Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[86] The Polish and Ukrainian Armies under Piłsudski's command launched a successful offensive against the Russian forces in Ukraine and on 7 May 1920, with remarkably little fighting, they captured Kiev.[87]

The Bolshevik leadership framed the Polish actions as an invasion, successfully generating popular support for their cause at home.[88] The Soviets then launched a counter-offensive from Belarus, and counterattacked in Ukraine, advancing into Poland[87] in a drive toward Germany to encourage the Communist Party of Germany in their struggles for power.[89] The Soviets announced their plans to invade Western Europe; Soviet Communist theoretician Nikolai Bukharin, writing in Pravda, hoped for the resources to carry the campaign beyond Warsaw "straight to London and Paris".[90] Soviet commander Mikhail Tukhachevsky's order of the day for 2 July 1920 read: "To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration. March upon Vilnius, Minsk, Warsaw!"[91] and "onward to Berlin over the corpse of Poland!"[49]

On 1 July 1920, in view of the rapidly advancing Soviet offensive, Poland's parliament, the Sejm, formed a Council for Defense of the Nation, chaired by Piłsudski, to provide expeditious decision-making as a temporary supplanting of the fractious Sejm.[92] The National Democrats contended that the string of Bolshevik victories had been Piłsudski's fault[93] and demanded that he resign; some even accused him of treason.[94] On 19 July they failed to carry a vote of no-confidence in the council and this led to Dmowski's withdrawal from the council.[94] On 12 August, Piłsudski tendered his resignation to Prime Minister Wincenty Witos, offering to be the scapegoat if the military solution failed, but Witos refused to accept his resignation.[94] The Entente pressured Poland to surrender and enter into negotiations with the Bolsheviks. Piłsudski, however, was a staunch advocate of continuing the fight.[94]

"Miracle at the Vistula"

Piłsudski's plan called for Polish forces to withdraw across the Vistula River and to defend the bridgeheads at Warsaw and on the Wieprz River while some 25% of the available divisions concentrated to the south for a counteroffensive. Afterwards, two armies under General Józef Haller, facing Soviet frontal attack on Warsaw from the east, were to hold their entrenched positions while an army under General Władysław Sikorski was to strike north from outside Warsaw, cutting off Soviet forces that sought to envelop the Polish capital from that direction. The most important role of the plan was assigned to a relatively small, approximately 20,000-man, newly assembled "Reserve Army" (also known as the "Strike Group", "Grupa Uderzeniowa"), comprising the most determined, battle-hardened Polish units that were commanded by Piłsudski. Their task was to spearhead a lightning northward offensive, from the Vistula-Wieprz triangle south of Warsaw, through a weak spot that had been identified by Polish intelligence between the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts. That offensive would separate the Soviet Western Front from its reserves and disorganize its movements. Eventually, the gap between Sikorski's army and the "Strike Group" would close near the East Prussian border, bringing about the destruction of the encircled Soviet forces.[95][96]

Piłsudski's plan was criticized as "amateurish" by high-ranking army officers and military experts, quick to point out Piłsudski's lack of formal military education. However, the desperate situation of the Polish forces persuaded other commanders to support it. When a copy of the plan was acquired by the Soviets, Western Front commander Mikhail Tukhachevsky thought it was a ruse and disregarded it.[97] Days later, the Soviets were defeated in the Battle of Warsaw, halting the Soviet advance in one of the worst defeats for the Red Army.[87][96] Stanisław Stroński, a National Democrat Sejm deputy, coined the phrase "Miracle at the Vistula" (Cud nad Wisłą)[98] to express his disapproval of Piłsudski's "Ukrainian adventure". Stroński's phrase was adopted as praise for Piłsudski by some patriotically- or piously minded Poles, who were unaware of Stroński's ironic intent.[96][99]

While Piłsudski had a major role in crafting the war strategy, he was aided by others, notably Tadeusz Rozwadowski.[100] Later, some supporters of Piłsudski would seek to portray him as the sole author of the Polish strategy, while his opponents would try to minimize his role.[101] On the other hand, in the West, the role of General Maxime Weygand of the French Military Mission to Poland was, for a time, exaggerated.[49][101][102]

In February 1921, Piłsudski visited Paris, where, in negotiations with French President Alexandre Millerand, he laid the foundations for the Franco-Polish alliance, which would be signed later that year.[103] The Treaty of Riga, ending the Polish-Soviet War in March 1921, partitioned Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Russia. Piłsudski called the treaty an "act of cowardice".[104] The treaty and his secret approval of General Lucjan Żeligowski's capture of Vilnius from the Lithuanians marked an end to this incarnation of Piłsudski's federalist Intermarium plan.[16] After Vilnius was occupied by the Central Lithuanian Army, Piłsudski said that he "could not help but regard them [Lithuanians] as brothers".[105] In parliament, Piłsudski once said: "I cannot not reach out to Kaunas. .. I cannot disregard those brothers who consider the day of our triumph a day of shock and mourning."[106] On 25 September 1921, when Piłsudski visited Lwów (now Lviv) for the opening of the first Eastern Trade Fair (Targi Wschodnie), he was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt by Stepan Fedak, acting on behalf of Ukrainian-independence organizations, including the Ukrainian Military Organization.[107]

Retirement and coup

The Polish Constitution of March 1921 severely limited the powers of the presidency intentionally, to prevent Piłsudski from waging war. This caused Piłsudski to decline to run for the office.[16] In the run-up to the first presidential election, a parliamentary election was held, in which Piłsudski endorsed two lists: the National-State Union, and the State Unity in the Kresy,[108] neither of which secured any seats in the Sejm. On 9 December 1922, the Polish National Assembly elected Gabriel Narutowicz of Polish People's Party "Wyzwolenie"; his election, opposed by the right-wing parties, caused public unrest.[109] On 14 December at the Belweder Palace, Piłsudski officially transferred his powers as Chief of State to his friend Narutowicz; the Naczelnik was replaced by the President.[110][44]

Two days later, on 16 December 1922, Narutowicz was shot dead by a right-wing painter and art critic, Eligiusz Niewiadomski, who had originally wanted to kill Piłsudski but had changed his target, influenced by National Democrat anti-Narutowicz propaganda.[111] For Piłsudski, that was a major shock; he started to doubt that Poland could function as a democracy[112] and supported a government led by a strong leader.[113] He became Chief of the General Staff and, together with Minister of Military Affairs Władysław Sikorski, quelled the unrest by instituting a state of emergency.[114]

Stanisław Wojciechowski of Polish People's Party "Piast" (PSL Piast), another of Piłsudski's old colleagues, was elected the new president, and Wincenty Witos, also of PSL Piast, became prime minister. The new government, an alliance among the centrist PSL Piast, the right-wing Popular National Union and Christian Democrat parties, contained right-wing enemies of Piłsudski. He held them responsible for Narutowicz's death and declared that it was impossible to work with them.[115] On 30 May 1923, Piłsudski resigned as Chief of the General Staff.[116]

Piłsudski criticized General Stanisław Szeptycki's proposal that the military should be supervised by civilians as an attempt to politicize the army, and on 28 June, he resigned his last political appointment. The same day, the Sejm's left-wing deputies voted for a resolution, thanking him for his work.[116] Piłsudski went into retirement in Sulejówek, outside Warsaw, at his country manor, "Milusin", presented to him by his former soldiers.[117] There, he wrote a series of political and military memoirs, including Rok 1920 (The Year 1920).[8]

Meanwhile, Poland's economy was a shambles. Hyperinflation fueled public unrest, and the government was unable to find a quick solution to the mounting unemployment and economic crisis.[118] Piłsudski's allies and supporters repeatedly asked him to return to politics, and he began to create a new power base, centred on former members of the Polish Legions, the Polish Military Organization and some left-wing and intelligentsia parties. In 1925, after several governments had resigned in short order and the political scene was becoming increasingly chaotic, Piłsudski became more and more critical of the government and eventually issued statements demanding the resignation of the Witos cabinet.[8][16] When the Chjeno-Piast coalition, which Piłsudski had strongly criticized, formed a new government,[16] on 12–14 May 1926, Piłsudski returned to power in the May Coup, supported by the Polish Socialist Party, Liberation, the Peasant Party, and the Communist Party of Poland.[119] Piłsudski had hoped for a bloodless coup but the government had refused to surrender;[120] 215 soldiers and 164 civilians had been killed, and over 900 persons had been wounded.[121]

In government

On 31 May 1926, the Sejm elected Piłsudski president of the Republic, but Piłsudski refused the office due to the presidency's limited powers. Another of his old friends, Ignacy Mościcki, was elected in his stead. Mościcki then appointed Piłsudski as Minister of Military Affairs (defence minister), a post he held for the rest of his life through eleven successive governments, two of which he headed from 1926 to 1928 and for a brief period in 1930. He also served as General Inspector of the Armed Forces and Chairman of the War Council.[8]

Piłsudski had no plans for major reforms; he quickly distanced himself from the most radical of his left-wing supporters and declared that his coup was to be a "revolution without revolutionary consequences".[16] His goals were to stabilize the country, reduce the influence of political parties (which he blamed for corruption and inefficiency) and strengthen the army.[16][122] His role in the Polish government over the subsequent years has been called a dictatorship or a "quasi-dictatorship".[123]

Internal politics

Piłsudski's coup entailed sweeping limitations on parliamentary government, as his Sanation government (1926–1939), at times employing authoritarian methods, sought to curb perceived corruption and incompetence of the parliament rule, and in Piłsudski's words, restore "moral health" to public life (hence the name of his faction, "Sanation", which could be understood as "moral purification").[124][1][2][3] From 1928, the Sanation government was represented by the Non-partisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR).[1][2][3] Popular support and an effective propaganda apparatus allowed Piłsudski to maintain his authoritarian powers, which could not be overruled either by the president, who was appointed by Piłsudski, or by the Sejm.[8] The powers of the Sejm were curtailed by constitutional amendments that were introduced soon after the coup, on 2 August 1926.[8] From 1926 to 1930, Piłsudski relied chiefly on propaganda to weaken the influence of opposition leaders.[16]

The culmination of his dictatorial and supralegal policies came in the 1930s, with the imprisonment and trial of political opponents (the Brest trials) on the eve of the 1930 Polish legislative election and with the 1934 establishment of the Bereza Kartuska Detention Camp for political prisoners in present-day Biaroza,[16] where some prisoners were brutally mistreated.[125] After the BBWR's 1930 victory, Piłsudski allowed most internal matters to be decided by his colonels while he concentrated on military and foreign affairs.[16] His treatment of political opponents and their 1930 arrest and imprisonment was internationally condemned and the events damaged Poland's reputation.[59]

Piłsudski became increasingly disillusioned with democracy in Poland.[126] His intemperate public utterances (he called the Sejm a "prostitute") and his sending of 90 armed officers into the Sejm building in response to an impending vote of no-confidence caused concern in contemporary and modern observers who have seen his actions as setting precedents for authoritarian responses to political challenges.[127][128][129] He sought to transform the parliamentary system into a presidential system; however, he opposed the introduction of totalitarianism.[16] The adoption of a new Polish constitution in April 1935 was tailored by Piłsudski's supporters to his specifications, providing for a strong presidency; but the April Constitution served Poland until World War II, and carried its Government in Exile until the end of the war and beyond. Piłsudski's government depended more on his charismatic authority than on rational-legal authority.[16] None of his followers could claim to be his legitimate heir, and after his death the Sanation structure would quickly fracture, returning Poland to the pre-Piłsudski era of parliamentary political contention.[16]

Piłsudski's government began a period of national stabilization and of improvement in the situation of ethnic minorities, which formed about a third of the Second Republic's population.[130][131] Piłsudski replaced the National Democrats' "ethnic-assimilation" with a "state-assimilation" policy: citizens were judged not by their ethnicity but by their loyalty to the state.[132][133] Widely recognized for his opposition to the National Democrats' anti-Semitic policies,[134][135][136][137][138][139] he extended his policy of "state-assimilation" to Polish Jews.[132][133][140][141] The years 1926 to 1935 and Piłsudski himself were favorably viewed by many Polish Jews whose situation improved especially under Piłsudski-appointed Prime Minister Kazimierz Bartel.[142][143] Many Jews saw Piłsudski as their only hope for restraining antisemitic currents in Poland and for maintaining public order; he was seen as a guarantor of stability and a friend of the Jewish people, who voted for him and actively participated in his political bloc.[144] Piłsudski's death in 1935 brought a deterioration in the quality of life of Poland's Jews.[139]

During the 1930s, a combination of developments, from the Great Depression[132] to the vicious spiral of OUN terrorist attacks and government pacifications, caused government relations with the national minorities to deteriorate.[132][145] Unrest among national minorities was also related to foreign policy. Troubles followed repressions in the largely-Ukrainian eastern Galicia, where nearly 1,800 persons were arrested. Tension also arose between the government and Poland's German minority, particularly in Upper Silesia. The government did not yield to calls for antisemitic measures, but the Jews (8.6% of Poland's population) grew discontented for economic reasons that were connected with the Depression. By the end of Piłsudski's life, his government's relations with national minorities were increasingly problematic.[146]

In the military sphere, Piłsudski was praised for his plan at the Battle of Warsaw in 1920, but was criticized for subsequently concentrating on personnel management and neglecting modernization of military strategy and equipment.[16][147] According to his detractors, his experiences in World War I and the Polish-Soviet War led him to over-estimate the importance of cavalry, and to neglect the development of armor and air forces.[147] His supporters, on the other hand, contend that, particularly from the late 1920s, he supported the development of these military branches.[148] Modern historians concluded that the limitations on Poland's military modernization in this period was less doctrinal than financial.[149]

Foreign policy

Piłsudski sought to maintain his country's independence in the international arena. Assisted by his protégé, Foreign Minister Józef Beck, he sought support for Poland in alliances with western powers, such as France and Britain, and with friendly neighbors such as Romania and Hungary.[150] A supporter of the Franco-Polish Military Alliance and the Polish–Romanian alliance, part of the Little Entente, Piłsudski was disappointed by the policy of appeasement pursued by the French and British governments, evident in their signing of the Locarno Treaties.[151][152][153] The Locarno treaties were intended by the British government to ensure a peaceful handover of the territories claimed by Germany such as the Sudetenland, the Polish Corridor, and the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk, Poland) by improving Franco-German relations to such extent that France would dissolve its alliances in eastern Europe.[154] Piłsudski aimed to maintain good relations with the Soviet Union and Germany,[151][152][153] and relations with Germany and the Soviet Union during Piłsudski's tenure could, for the most part, be described as neutral.[151][155] Under Piłsudski, Poland maintained good relations with neighboring Romania, Hungary and Latvia, but were strained with Czechoslovakia, and worse with Lithuania.[156]

A recurring fear of Piłsudski was that France would reach an agreement with Germany at the expense of Poland. In 1929, the French agreed to pull out of the Rhineland in 1930, five years earlier than the Treaty of Versailles specified. The same year, the French announced plans for the Maginot Line along the border with Germany, and construction of the Maginot line began in 1930. The Maginot line was a tacit French admission that Germany would be rearming beyond the limits set by the Treaty of Versailles in the near-future and that France intended to pursue a defensive strategy.[157] At the time Poland signed the alliance with France in 1921, the French were occupying the Rhineland and Polish plans for a possible war with Reich were based on the assumption of a French offensive into the north German plain from their bases in the Rhineland. The French pullout from the Rhineland and a shift to a defensive strategy as epitomized by the Maginot line completely upset the entire basis of Polish foreign and defense policy.[158]

In June 1932, just before the Lausanne Conference opened, Piłsudski heard reports that the new German chancellor Franz von Papen was about to make an offer for a Franco-German alliance to the French Premier Édouard Herriot which would be at the expense of Poland.[159] In response, Piłsudski sent the destroyer ORP Wicher into the harbour of Danzig.[159] Though the issue was ostensibly about access rights for the Polish Navy in Danzig, the real purpose of sending Wircher was as a way to warn Herriot not to disadvantage Poland in a deal with Papen.[159] The ensuring Danzig crisis sent the desired message to the French and improved the Polish Navy's access rights to Danzig.[159]

Poland signed the Soviet-Polish Non-Aggression Pact in 1932.[150] Critics of the pact state that it allowed Stalin to eliminate his socialist opponents, primarily in Ukraine. The pacts were supported by advocates of Piłsudski's Promethean programme.[160] After Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933, Piłsudski is rumored to have proposed to France a preventive war against Germany.[161] Lack of French enthusiasm may have been a reason for Poland signing the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact in 1934.[44][150][162][163] Little evidence has, however, been found in French or Polish diplomatic archives that such a proposal for preventive war was ever actually advanced.[164] Critics of Poland's pact with Germany accused Piłsudski of underestimating Hitler's aggressiveness,[165] and giving Germany time to re-arm.[166][167] Hitler repeatedly suggested a German-Polish alliance against the Soviet Union, but Piłsudski declined, instead seeking precious time to prepare for a potential war with either Germany or the Soviet Union. Just before his death, Piłsudski told Józef Beck that it must be Poland's policy to maintain neutral relations with Germany, keep up the Polish alliance with France and improve relations with the United Kingdom.[150] The two non-aggression pacts were intended to strengthen Poland's position in the eyes of its allies and neighbors.[8] Piłsudski was probably aware of the weakness of the pacts, stating: "Having these pacts, we are straddling two stools. This cannot last long. We have to know from which stool we will tumble first, and when that will be".[168]

Economic policy

Despite coming from a socialist background and initially implementing socialist reforms, Piłsudski's government followed the conservative free-market economic tradition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth throughout its existence. Poland had one of the lowest taxation rates in Europe, with 9.3% of taxes as a distribution of national income. Piłsudski's government was also heavily dependent on foreign investments and economies, with 45.4% of Polish equity capital controlled by foreign corporations. After the Great Depression, the Polish economy crumbled and failed to recover until Ignacy Mościcki's government introduced economic reforms with more government interventions with an increase in tax revenues and public spending after Piłsudski's death. These interventionist policies saw Poland's economy recover from the recession until the USSR and the German invasion of Poland in 1939.[169]

Religious views

Piłsudski's religious views are a matter of debate. He was baptised Roman Catholic on 15 December 1867 in the church of Powiewiórka (then Sventsiany deanery). His godparents were Joseph and Constance Martsinkovsky Ragalskaya.[170] On 15 July 1899, at the village of Paproć Duża, near Łomża, he married Maria Juskiewicz, a divorcée. As the Catholic Church did not recognise divorces, she and Piłsudski had converted to Protestantism.[171] Pilsudski later returned to the Catholic Church to marry Aleksandra Szczerbińska. Piłsudski and Aleksandra could not get married as Piłsudski's wife Maria refused to divorce him. It was only after Maria's death in 1921 that they were married, on 25 October that year.[172][173]

Death

By 1935, unbeknown to the public, Piłsudski had for several years been in declining health. On 12 May 1935, he died of liver cancer at Warsaw's Belweder Palace. The celebration of his life began spontaneously within half an hour of the announcement of his death.[174] It was led by military personnel – former Legionnaires, members of the Polish Military Organization, veterans of the wars of 1919–21 – and by his political collaborators from his service as Chief of State, and later, Prime Minister and Inspector-General.[175]

The Communist Party of Poland immediately smeared Piłsudski as a "fascist and capitalist",[175][full citation needed][176][full citation needed] Other opponents of the Sanation government were more civil; socialists (such as Ignacy Daszyński and Tomasz Arciszewski) and Christian Democrats (represented by Ignacy Paderewski, Stanisław Wojciechowski and Władysław Grabski) expressed condolences. The peasant parties split in their reactions. Wincenty Witos voiced criticism of Piłsudski. In contrast, Maciej Rataj and Stanisław Thugutt were supportive, while Roman Dmowski's National Democrats expressed a toned-down criticism.[175][full citation needed]

Condolences were officially expressed by senior clergy, including Pope Pius XI and August Cardinal Hlond, Primate of Poland. The Pope called himself a "personal friend" of Piłsudski. Notable appreciation for Piłsudski was expressed by Poland's ethnic and religious minorities. Eastern Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Protestant, Jewish, and Islamic organizations expressed condolences, praising Piłsudski for his policies of religious tolerance.[175] His death was a shock to members of the Jewish minority amongst which he was respected for his lack of prejudice and vocal opposition to the Endecja.[177][178] Mainstream organizations of ethnic minorities similarly expressed their support for his policies of ethnic tolerance, though he was still criticized by Ukrainian, German, Lithuanian activists and Jewish supporters of the General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland.[175] On the international scene, Pope Pius XI held a special ceremony on 18 May in the Holy See, a commemoration was conducted at League of Nations Geneva headquarters, and dozens of messages of condolence arrived in Poland from heads of state across the world, including Germany's Adolf Hitler, the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin, Italy's Benito Mussolini and King Victor Emmanuel III, France's Albert Lebrun and Pierre-Étienne Flandin, Austria's Wilhelm Miklas, Japan's Emperor Hirohito, and Britain's King George V.[175] In Berlin, a service for Piłsudski was ordered by Adolf Hitler. This was the only time that Hitler attended a Holy Mass as a leader of the Third Reich and probably one of the last times when he was in a church.[179]

Funeral

State funeral ceremonies for Piłsudski was held in Warsaw and Kraków between 15 and 18 May 1935, including official masses and funeral processions in both cities. A funeral train toured Poland before the remains of Piłsudski were laid to rest at Wawel.[180] A series of postcards, stamps and postmarks were also released to commemorate the event. The nation-wide ceremonies were accompanied by extensive media coverage and reflected the personality cult of Piłsudski. The final funeral procession in Krakow on 18 May, with an estimated 300,000 participants and official representatives from 16 foreign states, constituted the largest public funeral in Poland's history.[181] Separate funeral ceremonies were held for the burial of his brain, which Piłsudski had willed for study to Stefan Batory University, and his heart, which was interred in his mother's grave at Vilnius's Rasos Cemetery.[8][182]

In 1937, after a two-year display at St. Leonard's Crypt in Kraków's Wawel Cathedral, Piłsudski's remains were transferred to the cathedral's Crypt under the Silver Bells. The decision, made by his long-standing adversary Adam Sapieha, then Archbishop of Krakow, incited widespread protests that included calls for Sapieha's removal, setting off a series of clashes between the representatives of the Polish Catholic Church and the Polish government in what has come to be known as "konflikt wawelski" ("Wawel conflict"). Despite heavy and protracted criticism, Sapieha never allowed Piłsudski's coffin to be transferred back to St. Leonard's Crypt.[183][184]

Legacy

I am not going to dictate to you what you write about my life and work. I only ask that you not make me out to be a 'whiner and sentimentalist.'

— Józef Piłsudski, 1908[185]

On 13 May 1935, in accordance with Piłsudski's last wishes, Edward Rydz-Śmigły was named by Poland's president and government to be Inspector General of the Polish Armed Forces, and on 10 November 1936, he was elevated to Marshal of Poland.[186] As the Polish government became increasingly authoritarian and conservative, the Rydz-Śmigły faction was opposed by the more moderate Ignacy Mościcki, who remained President.[187] Although Rydz-Śmigły reconciled with the President in 1938, the ruling group remained divided into the "President's Men", mostly civilians (the "Castle Group", after the President's official residence, Warsaw's Royal Castle), and the "Marshal's Men" ("Piłsudski's colonels"), professional military officers and Piłsudski's old comrades-in-arms.[188] Some of this political division would continue in the Polish government-in-exile after the German invasion of Poland in 1939.[189][190]

After World War II, little of Piłsudski's political ideology influenced the policies of the Polish People's Republic, a de facto satellite of the Soviet Union.[191] For a decade after World War II, Piłsudski was either ignored or condemned by Poland's Communist government, along with the entire interwar Second Polish Republic. This began to change after de-Stalinization and the Polish October in 1956, and historiography in Poland gradually moved away from a purely negative view of Piłsudski toward a more balanced and neutral assessment.[192] After the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, Piłsudski once again came to be publicly acknowledged as a Polish national hero.[193] On the sixtieth anniversary of his death on 12 May 1995, Poland's Sejm adopted a resolution:

"Józef Piłsudski will remain, in our nation's memory, the founder of its independence and the victorious leader who fended off a foreign assault that threatened the whole of Europe and its civilization. Józef Piłsudski served his country well and has entered our history forever."[194]

Piłsudski continues to be viewed by most Poles as a providential figure in the country's 20th-century history.[195][196]

Several military units have been named for Piłsudski, including the 1st Legions Infantry Division, armoured train No. 51 ("I Marszałek"—"the First Marshal"),[197] and the Romanian 634th Infantry Battalion.[198] Also named for Piłsudski have been Piłsudski's Mound, one of four-man-made mounds in Kraków;[199] the Józef Piłsudski Institute of America, a New York City research center and museum on the modern history of Poland;[200] the Józef Piłsudski University of Physical Education in Warsaw;[201] a passenger ship, MS Piłsudski; a gunboat, ORP Komendant Piłsudski; and a racehorse, Pilsudski. Many Polish cities have their own "Piłsudski Street".[202] There are statues of Piłsudski in many Polish cities; Warsaw, which has three in little more than a mile between the Belweder Palace, Piłsudski's residence, and Piłsudski Square.[202] In 2020, Piłsudski's manor house in Sulejówek opened as a museum as part of the celebrations of the one hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Warsaw.[203]

Piłsudski has been a character in numerous works of fiction, a trend already visible during his lifetime,[204] including the 1922 novel Generał Barcz (General Barcz) by Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski.[205] Later works in which he is featured include the 2007 novel Ice (Lód) by Jacek Dukaj.[206] Poland's National Library lists over 500 publications related to Piłsudski;[207] the U.S. Library of Congress, over 300.[208] Piłsudski's life was the subject of a 2001 Polish television documentary, Marszałek Piłsudski, directed by Andrzej Trzos-Rastawiecki.[209] He was also the subject of paintings by artists such as Jacek Malczewski (1916) and Wojciech Kossak (leaning on his sword, 1928; and astride his horse, Kasztanka, 1928), as well as photos and caricatures.[210][211] He has been reported to be quite fond of the latter.[212]

Descendants

Both daughters of Marshal Piłsudski returned to Poland in 1990, after the Revolutions of 1989 and the fall of the Communist system. Jadwiga Piłsudska's daughter Joanna Jaraczewska returned to Poland in 1979. She married a Polish Solidarity activist Janusz Onyszkiewicz in a political prison in 1983. Both were very involved in the Solidarity movement between 1979 and 1989.[213]

Honours

Piłsudski was awarded numerous honours, domestic and foreign.

See also

- Józef Piłsudski's cult of personality

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s – 7 June 1926

- List of Poles

- Piłsudskiite (Piłsudczyk)

Notes

a. ^ Józef Klemens Piłsudski was commonly referred to without his middle name, as "Józef Piłsudski". A few English sources translate his first name as "Joseph", but this is not the common practice. As a young man, he belonged to underground organizations and used various pseudonyms, including "Wiktor", "Mieczysław" and "Ziuk" (the latter also being his family nickname). Later he was often affectionately called "Dziadek" ("Grandpa" or "the Old Man") and "Marszałek" ("the Marshal"). His ex-soldiers from the Legions also referred to him as "Komendant" ("the Commandant").

b. ^ Piłsudski sometimes spoke of being a Lithuanian of Polish culture.[214] For several centuries, declaring both Lithuanian and Polish identity was commonplace, but around the turn of the last century it became much rarer in the wake of arising modern nationalisms. Timothy Snyder, who calls him a "Polish-Lithuanian", notes that Piłsudski did not think in terms of 20th-century nationalisms and ethnicities; he considered himself both a Pole and a Lithuanian, and his homeland was the historic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[105]

c. ^ Polish Socialist Party – Revolutionary Faction from 1906 to 1909

References

- ^ a b c Puchalski, Piotr (2019). Beyond Empire: Interwar Poland and the Colonial Question, 1918–1939. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Press. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Kowalski, Wawrzyniec (2020). "From May to Bereza: A Legal Nihilism in the Political and Legal Practice of the Sanation Camp 1926–1935". Studia Iuridica Lublinensia (5). Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Sklodowskiej: 133–147. doi:10.17951/sil.2020.29.5.133-147. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Olstowski, Przemysław (2024). "The Formation of Authoritarian Rule in Poland between 1926 and 1939 as a Research Problem". Zapiski Historyczne (2). Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu: 27–60. doi:10.15762/ZH.2024.13. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

The case of authoritarian rule in Poland [...] following the May Coup of 1926, is notable for its unique origins [...] Rooted in a period when Poland lacked statehood [...] Polish authoritarianism evolved [...] Central to this phenomenon was Marshal Józef Piłsudski, the ideological leader of Poland's ruling camp after the May Coup of 1926

- ^ Hetherington 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Bianchini, Stefano (29 September 2017). Liquid Nationalism and State Partitions in Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-78643-661-0.

- ^ Hetherington 2012, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e Pidlutskyi 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "History – Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935)". Poland.gov. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Lerski 1996, p. 439.

- ^ Davies 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Bideleux & Jeffries 1998, p. 186.

- ^ Reddaway, William Fiddian (1939). Marshal Pilsudski. Routledge. p. 5.

- ^ Roshwald 2001, p. 36.

- ^ a b MacMillan 2003, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Chojnowski, Andrzej. "Piłsudski Józef Klemens". Internetowa encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ "Bronisław Piotr Piłsudski – Calendar of events". ICRAP. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 50.

- ^ Landau, Rom; Dunlop, Geoffrey (1930). Pilsudski, Hero of Poland. Jarrolds. pp. 30–32.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 62–66.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Jędrzejewicz & Cisek 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 71.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 88.

- ^ a b c MacMillan 2003, p. 209.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 93.

- ^ Piłsudski 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Alabrudzińska 1999, p. 99.

- ^ Garlicki 1995, p. 63.

- ^ Pobóg-Malinowski 1990, p. 7.

- ^ Jędrzejewicz 1990, pp. 27–8 (1982 ed.).

- ^ Drążek, Aleksandra (8 August 2021). "Córki Piłsudskiego - co wiemy o losach córek marszałka". kronikidziejow.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Charaszkiewicz 2000, p. 56.

- ^ Kowner 2006, p. 285.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zamoyski 1987, p. 330.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 113–116.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zamoyski 1987, p. 332.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 131.

- ^ a b Roos 1966, p. 14; Rothschild 1990, p. 45.

- ^ a b Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c d Józef Piłsudski at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Chimiak, Galia; Cierlik, Bożena (26 February 2020). Polish and Irish Struggles for Self-Determination: Living near Dragons. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-4764-3.

- ^ Joseph Conrad and his family – who had arrived in Kraków on 28 July 1914, exactly on the outbreak of World War I – in the first days of August took refuge in the Polish mountain resort of Zakopane. There Conrad opined – as Piłsudski had in Paris earlier in 1914 – that, for Poland to regain independence, Russia must be defeated by the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires), and the Central Powers must in turn be beaten by France and Britain. Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Rochester, New York, Camden House, 2007, ISBN 978-1-57113-347-2, p. 464. Soon after the war, Conrad said of Piłsudski: "He was the only great man to emerge on the scene during the war." Zdzisław Najder, Conrad under Familial Eyes, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-521-25082-X, p. 239.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 171–122.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cienciala 2002.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 170–171, 180–182.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel (31 May 2018). Polish Legions 1914–19. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4728-2543-8.

- ^ a b c Zamoyski 1987, p. 333.

- ^ May, Arthur J. (11 November 2016). The Passing of the Hapsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918, Volume 2. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-1-5128-0753-0.

- ^ Wróbel, Piotr J. (15 September 2010). "The Revival of Poland and Paramilitary Violence, 1918-1920". In Bergien, Rüdiger; Pröve, Ralf (eds.). Spießer, Patrioten, Revolutionäre: Militärische Mobilisierung und gesellschaftliche Ordnung in der Neuzeit (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 286. ISBN 978-3-86234-113-9.

- ^ Rąkowski 2005, pp. 109–11.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 251–252.

- ^ a b Biskupski 2000.

- ^ Rothschild 1990, p. 45.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 253.

- ^ "Dream of the Polish Eagle". Warfare History Network. October 2010.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 256, 277–278.

- ^ "Gdzie Piłsudski wysiadł z tramwaju, czyli historie poprzekręcane". histmag.org. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ ""Wysiadłem z czerwonego tramwaju...", czyli czego NIE powiedział Józef Piłsudski". Kurier Historyczny. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Suleja 2004, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d e MacMillan 2003, p. 210.

- ^ MacMillan 2003, pp. 213–214.

- ^ "The Versailles Treaty 28 June 1919: Part III". The Avalon Project. articles 87–93. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Grant 1999, p. 114.

- ^ MacMillan 2003, pp. 211, 214.

- ^ Boemeke et al. 1998, p. 314.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 499–501.

- ^ Jędrzejewicz 1990, p. 93.

- ^ Szymczak, Robert. "Polish-Soviet War: Battle of Warsaw". TheHistoryNet. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Sanford 2002, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Hyde-Price 2001, p. 75.

- ^ MacMillan 2003, p. 211.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 281.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, p. 90.

- ^ a b Kenez 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, p. 83.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 291.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, p. 45.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, p. 92.

- ^ Davies 2003, pp. 95ff.

- ^ a b c Davies 2003

- ^ Figes 1996, p. 699. "Within weeks of Brusilov's appointment, 14,000 officers had joined the army to fight the Poles, thousands of civilians had volunteered for war-work, and well over 100,000 deserters had returned to the Red Army on the Western Front".

- ^ See Lenin's speech on 22 September 1920 at the 9th Conference of the Russian Communist Party. English translation in Pipes 1993, pp. 181–182 and excerpts in Cienciala 2002. The speech was first published in Artizov, Andrey; Usov, R.A. (1992). ""Я прошу записывать меньше: это не должно попадать в печать ...": Выступления В.И.Ленина на IX конференции РКП(б) 22 сентября 1920 г.". Istoricheskii Arkhiv (in Russian). 1 (1). ISSN 0869-6322.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 101.

- ^ Lawrynowicz, Witold. "Battle of Warsaw 1920". Polish Militaria Collector's Association in memory of Andrzej Zaremba. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 341–346, 357–358.

- ^ Suleja 2004, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 341–346.

- ^ Cisek 2002, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b c Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 346–441 [357–358]

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Frątczak, Sławomir Z. (2005). "Cud nad Wisłą". Głos (in Polish) (32). Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ Davies 1998, p. 935.

- ^ Erickson 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b Lönnroth et al. 1994, p. 230.

- ^ Szczepański, Janusz. "Kontrowersje Wokół Bitwy Warszawskiej 1920 Roku (Controversies surrounding the Battle of Warsaw in 1920)". Mówią Wieki online (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 484.

- ^ Davies 2005, p. 399 (1982 ed. Columbia Univ. Press).

- ^ a b Snyder 2004, p. 70.

- ^ "Dialogas tarp lenkų ir lietuvių". Į Laisvę (in Lithuanian). 13 (50). 1957.

Pilsudskis seime kalbėjo; "Negaliu netiesti rankos Kaunui. .. negaliu nelaikyti broliais tų, kurie mūsų triumfo dieną laiko smūgio ir gedulo diena".

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 485.

- ^ Cat-Mackiewicz, Stanisław (2012). Historia Polski od 11 listopada 1918 do 17 września 1939. Universitas. ISBN 97883-242-3740-1.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 487–488.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 488.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 489.

- ^ Suleja 2004, p. 300.

- ^ Davies 1986, p. 140.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 489–490.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 490–491.

- ^ a b Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 490.

- ^ Watt 1979, p. 210.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 502.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, p. 515.

- ^ Suleja 2004, p. 343.

- ^ Roszkowski 1992, p. 53, section 5.1.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 528–539.

- ^ Biskupski 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Biskupski, M. B. B.; Pula, James S.; Wróbel, Piotr J. (15 April 2010). The Origins of Modern Polish Democracy. Ohio University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8214-4309-5.

- ^ Śleszyński, Wojciech (2003). "Aspekty prawne utworzenia obozu odosobnienia w Berezie Kartuskiej i reakcje środowisk politycznych. Wybór materiałów i dokumentów 1". Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne (in Polish). 20. Archived from the original on 25 March 2005 – via kamunikat / Belarusian history journal.

- ^ Cohen 1989, p. 65.

- ^ "Pilsudski Bros". Time. 7 April 1930. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Pilsudski v. Daszynski". Time. 11 November 1929. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (12 September 1993). "Visions of the Past Are Competing for Votes in Poland". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Stachura 2004, p. 79.

- ^ "Poland". Columbia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d Snyder 2004, p. 144.

- ^ a b Zimmerman 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Vital 1999, p. 788.

- ^ Payne 1995, p. 141.

- ^ Lieven 1994, p. 163.

- ^ Engelking 2001, p. 75.

- ^ Flannery 2005, p. 200.

- ^ a b Zimmerman 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Prizel 1998, p. 61.

- ^ Wein 1990, p. 292.

- ^ Cieplinski, Feigue (2002). "Poles and Jews: The Quest For Self-Determination 1919–1934". Binghamton University History Department. Archived from the original on 18 September 2002.

- ^ Paulsson 2003, p. 37.

- ^ Snyder 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Davies 2005, p. 407 (1982 ed. Columbia Univ. Press).

- ^ Leslie 1983, p. 182.

- ^ a b Garlicki 1995, p. 178.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, pp. 330–337.

- ^ Zaloga, Steve; Madej, W. Victor (1990). The Polish Campaign, 1939. Hippocrene Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-87052-013-6.

- ^ a b c d Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 539–540.

- ^ a b c Prizel 1998, p. 71.

- ^ a b Lukacs 2001, p. 30.

- ^ a b Jordan 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Schuker 1999, p. 48-49.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 538–540.

- ^ Goldstein 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Young 1996, p. 19-21.

- ^ Young 1996, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Wandycz 1988, p. 237.

- ^ Charaszkiewicz 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 2, pp. 317–326.

- ^ Torbus 1999, p. 25.

- ^ Quester 2000, p. 27. The author gives a source: Watt 1979.

- ^ Baliszewski, Dariusz (28 November 2004). "Ostatnia wojna marszałka". Wprost (in Polish) (48/2004, 1148). Agencja Wydawniczo-Reklamowa "Wprost". Retrieved 24 March 2005.

- ^ Hehn 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 237.

- ^ Davidson 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Kipp 1993, 95.

- ^ Dadak, Casimir (May 2012). "National Heritage and Economic Policies in Free and Sovereign Poland after 1918". Contemporary European History. 21 (2): 193–214. doi:10.1017/S0960777312000112. ISSN 1469-2171. S2CID 161683968.

- ^ [Adam Borkiewicz: Źródła do biografii Józefa Piłsudskiego the z lat 1867–1892, Niepodległość. T. XIX. Warszawa: 1939.]

- ^ Andrzej Garlicki, Józef Piłsudski: 1867–1935, Warsaw, Czytelnik, 1988, ISBN 8307017157, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Adviser Daria and Thomas, Jozef Pilsudski: Legends and Facts, Warsaw 1987, ISBN 83-203-1967-6, p. 132.]

- ^ Suleja Vladimir, Jozef Pilsudski, Wroclaw – Warsaw – Kraków 2005, ISBN 83-04-04706-3, pp. 290.

- ^ Drozdowski & Szwankowska 1995, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Drozdowski & Szwankowska 1995, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Ideas into Politics: Aspects of European History, 1880–1950 R. J. Bullen, Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, A. B. Polonsky, Taylor & Francis, 1984, p. 138

- ^ Joseph Marcus (18 October 2011). Social and Political History of the Jews in Poland 1919–1939. Walter de Gruyter. p. 349. ISBN 978-3-11-083868-8.

- ^ Aviva Woznica (11 April 2008). Fire Unextinguished. Xlibris Corporation. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4691-0600-7.

- ^ "Adolf Hitler attending memorial service of the Polish First Marshall Jozef Pilsudski in Berlin, 1935 – Rare Historical Photos". 3 December 2013.

- ^ Humphrey 1936, p. 295.

- ^ Kowalski, Waldemar (2017). "Piłsudski pośród królów - droga marszałka na Wawel". dzieje.pl Portal Historyczny (in Polish). Polish Press Agency. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Watt 1979, p. 338.

- ^ To, Wireless (26 June 1937). "Crowds urge Poland to banish Archbishop; Pilsudski Legionnaires also Assail Catholic Church on the Removal of Marshal's Body". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ Lerski 1996, p. 525.

- ^ Urbankowski 1997, vol. 1, pp. 133–141.

- ^ Jabłonowski & Stawecki 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Jabłonowski & Stawecki 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Andrzej Ajnenkiel; Andrzej Drzycimski; Janina Paradowska (1991). Prezydenci Polski (in Polish). Wydawn. Sejmowe. p. 62. ISBN 9788370590000.

grupa pułkowników, zespół wywodzących się z wojska najbliższych współpracowników Marszałka, takich jak płk Sławek czy płk Prystor; ich koncepcje różniły się wyraźnie od stanowiska zajmowanego przez prezydenta.

- ^ Dworski, Michał (2018). "Republic in Exile ͵ Political Life of Polish Emigration in United Kingdom After Second World War". Toruńskie Studia Międzynarodowe. 1 (10): 101–110. doi:10.12775/TSM.2017.008. ISSN 2391-7601.

- ^ Pra ż mowska, Anita (1 July 2013). "The Polish Underground Resistance During the Second World War: A Study in Political Disunity During Occupation". European History Quarterly. 43 (3): 464–488. doi:10.1177/0265691413490495. ISSN 0265-6914. S2CID 220737108.

- ^ Charaszkiewicz 2000, p. 56

- ^ Władyka 2005, pp. 285–311; Żuławnik, Małgorzata & Mariusz 2005.

- ^ Roshwald 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Translation of Oświadczenie Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 12 maja 1995 r. w sprawie uczczenia 60 rocznicy śmierci Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego. (MP z dnia 24 maja 1995 r.). For Polish original online, see here [1].

- ^ K. Kopp; J. Nizynska (7 May 2012). Germany, Poland and Postmemorial Relations: In Search of a Livable Past. Springer. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-1-137-05205-6.

- ^ Ahmet Ersoy; Maciej G¢rny; Vangelis Kechriotis (1 January 2010). Modernism: The Creation of Nation-States: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe 1770?1945: Texts and Commentaries, Volume III/1. Central European University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-963-7326-61-5.

- ^ "Polish Armoured Train Nr. 51 ("I Marszałek")". PIBWL (Prywatny Instytut Badawczy Wojsk Lądowych). Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- ^ "De ce Batalionul 634 Infanterie din Piatra-Neamț se numește "Mareşal Józef Piłsudski"?". ziarpiatraneamt.ro (in Romanian). 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Kopiec Józefa Piłsudskiego". Pedagogical University of Kraków (in Polish). Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "Józef Piłsudski Institute of America Welcome Page". Józef Piłsudski Institute of America. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ "Józef Piłsudski Academy of Physical Education in Warsaw". Polish Ministry of Education and Science. Archived from the original on 23 September 2005. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- ^ a b Jonathan D. Smele (19 November 2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-4422-5281-3.

- ^ "House and home: Piłsudski's old manor opens as museum". Retrieved 16 August 2020.