Isoquinoline alkaloids

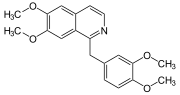

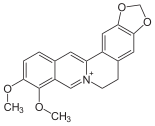

Isoquinoline alkaloids are natural products of the group of alkaloids, which are chemically derived from isoquinoline. They form the largest group among the alkaloids.[1]

Isoquinoline alkaloids can be further classified based on their different chemical basic structures. The most common structural types are the benzylisoquinolines and the aporphines.[2] According to current knowledge, a total of about 2500 isoquinoline alkaloids are known nowadays, which are mainly formed by plants.[3]

Known examples

Occurrence in nature

The isoquinoline alkaloids are primarily formed in the plant families of Papaveraceae, Berberidaceae, Menispermaceae, Fumariaceae and Ranunculaceae.

The opium poppy, which belongs to the Papavaraceae family, is of great interest, since the isoquinoline alkaloids morphine, codeine, papaverine, noscapine and thebaine can be found in its latex.[3] In addition to the opium poppy, there are other poppy plants, such as the celandine, in which isoquinoline alkaloids are found. Their latex contains berberine, which also occurs in other plant families, such as the Berberidaceae.[4] An example of the Berberidaceae with the ingredient berberine is Berberis vulgaris.[5]

The alkaloid tubocurarin is found in the hairy cartilage tree. There the Tubocurarin is extracted from the bark and roots.[6]

- Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy, contains a wealth of alkaloids, including morphine, codeine and papaverine

- Stylophorum diphyllum, the celandine poppy, contains berberine

- Berberis vulgaris, the common barberry, contains berberine

Biological effect

In general, isoquinoline alkaloids can have different effects. The opium alkaloids may have sedative, psychotropic or analgesic properties.[7] Morphine and codeine are indeed used as analgesics.[8]

Papaverine, in contrast, has an antispasmodic effect if it comes from smooth muscles, as is the case in humans in the gastrointestinal tract or blood vessels. This is why it is used as an antispasmodic.[9]

Tubocurarin impairs the transmission of stimuli in the nervous system, so that paralysis may occur in the affected organism.[10]

References

- ^ Gerhard Habermahl, Peter E. Hammann, Hans C. Krebs, Waldemar Ternes: Naturstoffe. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/ Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-73733-9, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73733-9, S. 176–187.

- ^ Bettina Ruff: Chemische und biochemische Methoden zur stereoselektiven Synthese von komplexen Naturstoffen. Verlag Logos, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-8325-3121-8, S. 8. ([1], p. 8, at Google Books)

- ^ a b Jennifer M. Finefield, David H. Sherman, Martin Kreitman, Robert M. Williams: Enantiomere Naturstoffe: Vorkommen und Biogenese. In: Angewandte Chemie. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2012, doi:10.1002/ange.201107204, S. 4905–4915.

- ^ A. Husemann, T. Husemann: Die Pflanzenstoffe in chemischer, physiologischer, pharmakologischer und toxikologischer Hinsicht. Berlin 1871, S. 245–253. (Digitalisat Bayerische Staatsbibliothek).

- ^ Entry on Berberin. at: Römpp Online. Georg Thieme Verlag, retrieved 13. Dezember 2017.

- ^ Rudolf Hänsel, Josef Hölzl: Lehrbuch der pharmazeutischen Biologie. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/ Heidelberg/ New York 2012, 1996, ISBN 3-642-64628-X, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60958-9, S. 302.

- ^ Rainer Nowack: Notfallhandbuch Giftpflanzen: Ein Bestimmungsbuch für Ärzte und Apotheker. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/ Heidelberg 1998, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-58885-3, S. 258.

- ^ Jens Frackenpohl: Morphin und Opioid-Analgetika. In: Chemie unserer Zeit. WILEY-VCH, Weinheim, 2000, doi:10.1002/1521-3781(200004)34, S. 99–112.

- ^ Franz v. Bruchhausen, Gerd Dannhardt, Siegfried Ebel, August-Wilhelm Frahm, Eberhard Hackenthal, Ulrike Holzgrabe: Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis. 5. Auflage. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/ Heidelberg 1994, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-57880-9, S. 16.

- ^ Heinz Lüllmann, Klaus Mohr, Lutz Hein: Pharmakologie und Toxikologie. 16. Auflage. Georg-Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart/ New York 2006, ISBN 3-13-368516-3, S. 255–258.