Spread of Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamization |

|---|

|

The spread of Islam spans almost 1,400 years. The early Muslim conquests that occurred following the death of Muhammad in 632 CE led to the creation of the caliphates, expanding over a vast geographical area; conversion to Islam was boosted by Arab Muslim forces expanding over vast territories and building imperial structures over time.[1][2][3][4] Most of the significant expansion occurred during the reign of the rāshidūn ("rightly-guided") caliphs from 632 to 661 CE, which were the first four successors of Muhammad.[4] These early caliphates, coupled with Muslim economics and trading, the Islamic Golden Age, and the age of the Islamic gunpowder empires, resulted in Islam's spread outwards from Mecca towards the Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans and the creation of the Muslim world. The Islamic conquests, which culminated in the Arab empire being established across three continents (Asia, Africa, and Europe), enriched the Muslim world, achieving the economic preconditions for the emergence of this institution owing to the emphasis attached to Islamic teachings.[5] Trade played an important role in the spread of Islam in some parts of the world, such as Indonesia.[6][7] During the early centuries of Islamic rule, conversions in the Middle East were mainly individual or small-scale. While mass conversions were favored for spreading Islam beyond Muslim lands, policies within Muslim territories typically aimed for individual conversions to weaken non-Muslim communities. However, there were exceptions, like the forced mass conversion of the Samaritans.[8]

Muslim dynasties were soon established and subsequent empires such as those of the Umayyads, Abbasids, Mamluks, Seljukids, and the Ayyubids were among some of the largest and most powerful in the world. The Ajuran and Adal Sultanates, and the wealthy Mali Empire, in North Africa, the Delhi, Deccan, and Bengal Sultanates, and Mughal and Durrani Empires, and Kingdom of Mysore and Nizam of Hyderabad in the Indian subcontinent, the Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Samanids in Persia, Timurids, and the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia significantly changed the course of history. The people of the Islamic world created numerous sophisticated centers of culture and science with far-reaching mercantile networks, travelers, scientists, hunters, mathematicians, physicians, and philosophers, all contributing to the Islamic Golden Age. The Timurid Renaissance and the Islamic expansion in South and East Asia fostered cosmopolitan and eclectic Muslim cultures in the Indian subcontinent, Malaysia, Indonesia and China.[9] The Ottoman Empire, which controlled much of the Middle East and North Africa in the early modern period, also did not officially endorse mass conversions, but evidence suggests they occurred, particularly in the Balkans, often to evade the jizya tax. Similarly, Christian sources mention requests for mass conversions to Islam, such as in Cyprus, where Ottoman authorities refused, fearing economic repercussions.[8]

As of 2016, there were 1.7 billion Muslims,[10][11] with one out of four people in the world being Muslim,[12] making Islam the second-largest religion.[13] Out of children born from 2010 to 2015, 31% were born to Muslims,[14] and currently Islam is the world's fastest-growing major religion .[15][16][17]

Terminology

Alongside the terminology of the "spread of Islam", scholarship of the subject has also given rise to the terms "Islamization",[a] "Islamicization",[18] and "Islamification" (Arabic: أسلمة, romanized: aslamah). These terms are used concurrently with the terminology of the "spread of Islam" to refer to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occurred over the course of many centuries since the spread of Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula through the early Muslim conquests, with notable shifts occurring in the Levant, Iran, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, West Africa,[19] Central Asia, South Asia (in Afghanistan, Maldives, Pakistan, and Bangladesh), Southeast Asia (in Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia), Southeastern Europe (in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo, among others), Eastern Europe (in the Caucasus, Crimea, and the Volga), and Southern Europe (in Spain, Portugal, and Sicily prior to re-Christianizations).[20] In contemporary usage, "Islamization" and its variants too can also be used with implied negative connotations to refer to the perceived imposition of an Islamist social and political system on a society with an indigenously different social and political background.

The English synonym of "Muslimization", in use since before 1940 (e.g., Waverly Illustrated Dictionary), conveys a similar meaning as "Islamization". 'Muslimization' has more recently also been used as a term coined to describe the overtly Muslim practices of new converts to the religion who wish to reinforce their newly acquired religious identity.[21]

Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates (610–750)

Within the century of the establishment of Islam upon the Arabian Peninsula and the subsequent rapid expansion during the early Muslim conquests, one of the most significant empires in world history was formed.[22] For the subjects of the empire, formerly of the Byzantine and the Sasanian Empires, not much changed in practice. The objective of the conquests was mostly of a practical nature, as fertile land and water were scarce in the Arabian Peninsula. A real Islamization therefore came about only during the subsequent centuries.[23]

Ira M. Lapidus distinguishes between two separate strands of converts of the time: animists and polytheists of tribal societies of the Arabian Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent and the native Christians and Jews existing before the Muslims arrived.[24]

The empire spread from the Atlantic Ocean to the Aral Sea, from the Atlas Mountains to the Hindu Kush. It was bounded mostly by "a combination of natural barriers and well-organized states".[25]

For the polytheistic and pagan societies, apart from the religious and spiritual reasons that individuals may have had, conversion to Islam "represented the response of a tribal, pastoral population to the need for a larger framework for political and economic integration, a more stable state, and a more imaginative and encompassing moral vision to cope with the problems of a tumultuous society."[24] In contrast, for tribal, nomadic, monotheistic societies, "Islam was substituted for a Byzantine or Sassanian political identity and for a Christian, Jewish or Zoroastrian religious affiliation."[24] Conversion initially was neither required nor necessarily wished for: "(The Arab conquerors) did not require the conversion as much as the subordination of non-Muslim peoples. At the outset, they were hostile to conversions because new Muslims diluted the economic and status advantages of the Arabs."[24]

Only in subsequent centuries, with the development of the religious doctrine of Islam and with that the understanding of the Muslim ummah, would mass conversion take place. The new understanding by the religious and political leadership in many cases led to a weakening or breakdown of the social and religious structures of parallel religious communities such as Christians and Jews.[24]

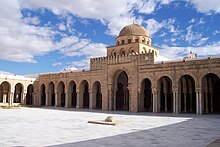

The caliphs of the Arab dynasty established the empire's first school, which taught the Arabic language and Islamic studies. The caliphs furthermore began the ambitious project of building mosques across the empire, many of which remain today, such as the Umayyad Mosque, in Damascus. At the end of the Umayyad period, less than 10% of the people in Iran, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Tunisia and Spain were Muslim. Only the Arabian Peninsula had a higher proportion of Muslims among the population.[26]

Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258)

The Abbasids replaced the expanding empire and "tribal politics" of "the tight-knit Arabian elite[25] with cosmopolitan culture and disciplines of Islamic science,[25] philosophy, theology, law and mysticism became more widespread, and the gradual conversions of the empire's populations occurred. Significant conversions also occurred beyond the extent of the empire such as that of the Turkic tribes in Central Asia and peoples living in regions south of the Sahara and north of the Sahel in Africa through contact with Muslim traders active in the area and Sufi orders. In Africa, Islam spread along three routes, across the Sahara and Sahel via trading towns such as Timbuktu, up the Nile Valley through the Sudan up to Uganda and across the Red Sea and down East Africa through settlements such as Mombasa and Zanzibar. The initial conversions were of a flexible nature.

The reasons that by the end of the 10th century, a large part of the population had converted to Islam are diverse. According to the British-Lebanese historian Albert Hourani, one of the reasons may be that

"Islam had become more clearly defined, and the line between Muslims and non-Muslims more sharply drawn. Muslims now lived within an elaborated system of ritual, doctrine and law clearly different from those of non-Muslims. (...) The status of Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians was more precisely defined, and in some ways it was inferior. They were regarded as the 'People of the Book', those who possessed a revealed scripture, or 'People of the Covenant', with whom compacts of protection had been made. In general, they were not forced to convert, but they suffered from restrictions. They paid a special tax; they were not supposed to wear certain colors; they could not marry Muslim women;."[26]

Most of those laws were elaborations of basic laws concerning non-Muslims (dhimmis) in the Quran, which does not give much detail about the right conduct with non-Muslims, but it in principle recognises the religion of "People of the Book" (Jews, Christians and sometimes others as well) and securing a separate tax from them that replaces the zakat, which is imposed upon Muslim subjects.

Ira Lapidus points towards "interwoven terms of political and economic benefits and of a sophisticated culture and religion" as appealing to the masses.[27] He noted:

"The question of why people convert to Islam has always generated the intense feeling. Earlier generations of European scholars believed that conversions to Islam were made at the point of the sword, and that conquered peoples were given the choice of conversion or death. It is now apparent that conversion by force, while not unknown in Muslim countries, was, in fact, rare. Muslim conquerors ordinarily wished to dominate rather than convert, and most conversions to Islam were voluntary. (...) In most cases, worldly and spiritual motives for conversion blended together. Moreover, conversion to Islam did not necessarily imply a complete turning from an old to a totally new life. While it entailed the acceptance of new religious beliefs and membership in a new religious community, most converts retained a deep attachment to the cultures and communities from which they came."[27]

The result, he points out, can be seen in the diversity of Muslim societies today, with varying manifestations and practices of Islam.

Conversion to Islam also came about as a result of the breakdown of historically-religiously organized societies: with the weakening of many churches, for example, and the favouring of Islam and the migration of substantial Muslim Turkish populations into the areas of Anatolia and the Balkans, the "social and cultural relevance of Islam" were enhanced and a large number of peoples were converted. This worked better in some areas (Anatolia) and less in others (such as the Balkans in which "the spread of Islam was limited by the vitality of the Christian churches".)[24]

During the Abbasid period, economic hardships, social disorder, and pressure from Muslim attackers, led to the mass conversion of Samaritans to Islam.[28]

Along with the religion of Islam, the Arabic language, Arabic numerals and Arab customs spread throughout the empire. A sense of unity grew among many though not all provinces and gradually formed the consciousness of a broadly Arab-Islamic population. What was recognizably an Islamic world had emerged by the end of the 10th century.[29] Throughout the period, as well as in the following centuries, divisions occurred between Persians and Arabs, and Sunnis and Shias, and unrest in provinces empowered local rulers at times.[26]

Seljuk and Ottoman states (950–1450)

The expansion of Islam continued in the wake of Turkic conquests of Asia Minor, the Balkans and the Indian subcontinent.[22] The earlier period also saw the acceleration in the rate of conversions in the Muslim heartland, and in the wake of the conquests, the newly-conquered regions retained significant non-Muslim populations. That was contrast to the regions in which the boundaries of the Muslim world contracted, such as the Emirate of Sicily (Italy) and Al Andalus (Spain and Portugal), where Muslim populations were expelled or forced to Christianize in short order.[22] The latter period of that phase was marked by the Mongol invasion (particularly the Siege of Baghdad in 1258) and, after an initial period of persecution, the conversion of those conquerors to Islam.

Ottoman Empire (1299–1924)

The Ottoman Empire defended its frontiers initially against threats from several sides: the Safavids in the east, the Byzantine Empire in the north until it vanished with the Conquest of Constantinople in 1453, and the great Catholic powers from the Mediterranean Sea: Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, and Venice with its eastern Mediterranean colonies.

Later, the Ottoman Empire set on to conquer territories from these rivals: Cyprus and other Greek islands (except Crete) were lost by Venice to the Ottomans, and the latter conquered territory up to the Danube basin as far as Hungary. Crete was conquered during the 17th century, but the Ottomans lost Hungary to the Holy Roman Empire, and other parts of Eastern Europe, which ended with the Treaty of Carlowitz in 1699.[30]

The Ottoman sultanate was abolished on 1 November 1922 and the caliphate was abolished on 3 March 1924.[31]

20th and 21st centuries

Islam has continued to spread through commerce and migrations, especially in Southeast Asia, America and Europe.[22]

Modern day Islamization appears to be a return of the individual to Muslim values, communities, and dress codes, and a strengthened community.[32]

Another development is that of transnational Islam, elaborated upon by the French Islam researchers Gilles Kepel and Olivier Roy. It includes a feeling of a "growing universalistic Islamic identity" as often shared by Muslim immigrants and their children who live in non-Muslim countries:

The increased integration of world societies as a result of enhanced communications, media, travel, and migration makes meaningful the concept of a single Islam practiced everywhere in similar ways, and an Islam which transcends national and ethnic customs.[33]

This does not necessarily imply political or social organizations:

Global Muslim identity does not necessarily or even usually imply organized group action. Even though Muslims recognize a global affiliation, the real heart of Muslim religious life remains outside politics—in local associations for worship, discussion, mutual aid, education, charity, and other communal activities.[33]

A third development is the growth and elaboration of transnational military organizations. The 1980s and 90s, with several major conflicts in the Middle East, including the Arab–Israeli conflict, Afghanistan in the 1980s and 2001, and the three Gulf Wars (1980–88, 1990–91, 2003–2011) were catalysts of a growing internationalization of local conflicts. [citation needed] Figures such as Osama bin Laden and Abdallah Azzam have been crucial in these developments, as much as domestic and world politics.[33]

Character of conversion

Muslim Arab expansion in the first centuries after Muhammad's death soon established dynasties in North Africa, West Africa, to the Middle East, and south to Somalia by the Companions of the Prophet, most notably the Rashidun Caliphate and military advents of Khalid Bin Walid, Amr ibn al-As, and Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas. The historic process of Islamization was complex and involved merging Islamic practices with local customs. This process took place over several centuries. Some scholars reject the stereotype that this process was initially "spread by the sword" or forced conversions.[34]

There are a number of historians who see the rule of the Umayyads as responsible for setting up the "dhimmah" to increase taxes from the dhimmis to benefit the Arab Muslim community financially and to discourage conversion.[35] Islam was initially associated with the Arabs' ethnic identity and required formal association with an Arab tribe and the adoption of the client status of mawali.[35] Governors lodged complaints with the caliph when he enacted laws that made conversion easier since that deprived the provinces of revenues from the tax on non-Muslims. An enfranchisement was experienced by the mawali during the Abbasid period, and a shift was made in the political conception from that of a primarily-Arab empire to one of a Muslim empire.[36] Around 930 a law was enacted that required all bureaucrats of the empire to be Muslims.[35] Both periods were also marked by significant migrations of Arab tribes outwards from the Arabian Peninsula into the new territories.[36]

Richard Bulliet's "conversion curve" shows a relatively low rate of conversion of non-Arab subjects during the Arab centric Umayyad period of 10%, in contrast with estimates for the more politically-multicultural Abbasid period, which saw the Muslim population grow from around 40% in the mid-9th century, with almost the entire population being converted by the end of the 11th century.[36] That theory does not explain the continuing existence of large minorities of Christians during the Abbasids.[original research?] Other estimates suggest that Muslims were not a majority in Egypt until the mid-10th century and in the Fertile Crescent until 1100. What is now Syria may have had a Christian majority until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.[citation needed]

By region

Arabia

At Mecca, Muhammad is said to have received repeated embassies from Christian tribes.

Greater Syria

Like their Byzantine and late Sasanian predecessors, the Marwanid caliphs nominally ruled the various religious communities but allowed the communities' own appointed or elected officials to administer most internal affairs. Yet the Marwanids also depended heavily on the help of non-Arab administrative personnel and on administrative practices (e.g., a set of government bureaus). As the conquests slowed and the isolation of the fighters (muqatilah) became less necessary, it became more and more difficult to keep Arabs garrisoned. As the tribal links that had so dominated Umayyad politics began to break down, the meaningfulness of tying non-Arab converts to Arab tribes as clients was diluted; moreover, the number of non-Muslims who wished to join the ummah was already becoming too large for this process to work effectively.

Palestine

The Siege of Jerusalem (636–637) by the forces of the Rashid Caliph Umar against the Byzantines began in November 636. For four months, the siege continued. Ultimately, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, an ethnic Arab,[37] agreed to surrender Jerusalem to Umar in person. The caliph, then in Medina, agreed to these terms and travelled to Jerusalem to sign the capitulation in the spring of 637.

Sophronius also negotiated a pact with Umar known as Umar's Assurance, allowing for the religious freedom for Christians in exchange for jizya, a tax to be paid by conquered non-Muslims, called dhimmis. Under Muslim rule, the Jewish and Christian population of Jerusalem in this period enjoyed the usual tolerance given to non-Muslim theists.[38][39]

Having accepted the surrender, Omar then entered Jerusalem with Sophronius "and courteously discoursed with the patriarch concerning its religious antiquities".[40] When the hour for his prayer came, Omar was in the Anastasis church, but refused to pray there, lest in the future Muslims should use that as an excuse to break the treaty and confiscate the church. The Mosque of Umar, opposite the doors of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with the tall minaret, is known as the place to which he retired for his prayer.

Bishop Arculf, whose account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the seventh century, De locis sanctis, written down by the monk Adamnan, described reasonably pleasant living conditions of Christians in Palestine in the first period of Muslim rule. The caliphs of Damascus (661-750) were tolerant princes who were on generally good terms with their Christian subjects. Many Christians, such as John of Damascus, held important offices at their court. The Abbasid caliphs at Baghdad (753-1242), as long as they ruled Syria, were also tolerant to Christians. Harun Abu Jaʻfar (786-809), sent the keys of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to Charlemagne, who built a hospice for Latin pilgrims near the shrine.[38]

Rival dynasties and revolutions led to the eventual disunion of the Muslim world. In the ninth century, Palestine was conquered by the Fatimid Caliphate, whose capital was Cairo. Palestine once again became a battleground as the various enemies of the Fatimids counterattacked. At the same time, the Byzantines continued to attempt to regain their lost territories, including Jerusalem. Christians in Jerusalem who sided with the Byzantines were put to death for high treason by the ruling Shiʻi Muslims. In 969, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, John VII, was put to death for treasonous correspondence with the Byzantines.

As Jerusalem grew in importance to Muslims and pilgrimages increased, tolerance for other religions declined. Christians were persecuted and churches destroyed. The Sixth Fatimid caliph, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, 996–1021, who was believed to be "God made manifest" by his most zealous Shiʻi followers, now known as the Druze, destroyed the Holy Sepulchre in 1009. This powerful provocation helped ignite the flame of fury that led to the First Crusade.[38] The dynasty was later overtaken by Saladin of the Ayyubid dynasty.

Africa

North Africa

In Egypt conversion to Islam was initially considerably slower than in other areas such as Mesopotamia or Khurasan, with Muslims not thought to have become the majority until around the fourteenth century.[42] In the initial invasion, the victorious Muslims granted religious freedom to the Christian community in Alexandria, and the Alexandrians quickly recalled their exiled Monophysite patriarch to rule over them, subject only to the ultimate political authority of the conquerors. In such a fashion the city persisted as a religious community under an Arab Muslim domination more welcome and more tolerant than that of Byzantium.[43] (Other sources question how much the native population welcomed the conquering Muslims.)[44]

Byzantine rule was ended by the Arabs, who invaded Tunisia from 647 to 648[45] and Morocco in 682 in the course of their drive to expand the power of Islam. In 670, the Arab general and conqueror Uqba Ibn Nafi established the city of Kairouan (in Tunisia) and its Great Mosque also known as the Mosque of Uqba;[46] the Great Mosque of Kairouan is the ancestor of all the mosques in the western Islamic world.[41] Berber troops were used extensively by the Arabs in their conquest of Spain, which began in 711.

No previous conqueror had tried to assimilate the Berbers, but the Arabs quickly converted them and enlisted their aid in further conquests. Without their help, for example, Andalusia could never have been incorporated into the Islamic state. At first only Berbers nearer the coast were involved, but by the 11th century Muslim affiliation had begun to spread far into the Sahara and Sahel.[47]

The conventional historical view is that the conquest of North Africa by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate between CE 647–709 effectively ended Catholicism in Africa for several centuries.[48] However, new scholarship has appeared that provides more nuance and details of the conversion of the Christian inhabitants to Islam. A Christian community is recorded in 1114 in Qal'a in central Algeria. There is also evidence of religious pilgrimages after 850 CE to tombs of Catholic saints outside of the city of Carthage, and evidence of religious contacts with Christians of Arab Spain. In addition, calendar reforms adopted in Europe at this time were disseminated amongst the indigenous Christians of Tunis, which would have not been possible had there been an absence of contact with Rome.

During the reign of Umar II, the then governor of Africa, Ismail ibn Abdullah, was said to have won the Berbers to Islam by his just administration, and other early notable missionaries include Abdallah ibn Yasin who started a movement which caused thousands of Berbers to accept Islam.[49]

Horn of Africa

The history of commercial and intellectual contact between the inhabitants of the Somalia and the Arabian Peninsula may help explain the Somali people's connection with Muhammad. The early Muslims fled to the port city of Zeila in modern-day Somaliland to seek protection from the Quraysh at the court of the Aksumite Emperor in present-day Ethiopia. Some of the Muslims that were granted protection are said to have then settled in several parts of the Horn region to promote the religion. The victory of the Muslims over the Quraysh in the 7th century had a significant impact on local merchants and sailors, as their trading partners in Arabia had then all adopted Islam, and the major trading routes in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea came under the sway of the Muslim Caliphs. Through commerce, Islam spread amongst the Somali population in the coastal cities. Instability in the Arabian peninsula saw further migrations of early Muslim families to the Somali seaboard. These clans came to serve as catalysts, forwarding the faith to large parts of the Horn region.[50]

East Africa

On the east coast of Africa, where Arab mariners had for many years journeyed to trade, mainly in slaves, Arabs founded permanent colonies on the offshore islands, especially on Zanzibar, in the 9th and 10th century. From there Arab trade routes into the interior of Africa helped the slow acceptance of Islam.

By the 10th century, the Kilwa Sultanate was founded by Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi (was one of seven sons of a ruler of Shiraz, Persia, his mother an Abyssinian slave girl. Upon his father's death, Ali was driven out of his inheritance by his brothers). His successors would rule the most powerful of Sultanates in the Swahili coast, during the peak of its expansion the Kilwa Sultanate stretched from Inhambane in the south to Malindi in the north. The 13th-century Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta noted that the great mosque of Kilwa Kisiwani was made of coral stone (the only one of its kind in the world).

In the 20th century, Islam grew in Africa both by birth and by conversion. The number of Muslims in Africa grew from 34.5 million in 1900 to 315 million in 2000, going from roughly 20% to 40% of the total population of Africa.[51] However, in the same time period, the number of Christians also grew in Africa, from 8.7 million in 1900 to 346 million in 2000, surpassing both the total population as well as the growth rate of Islam on the continent.[51][52]

Western Africa

The spread of Islam in Africa began in the 7th to 9th century, brought to North Africa initially under the Umayyad Dynasty. Extensive trade networks throughout North and West Africa created a medium through which Islam spread peacefully, initially through the merchant class. By sharing a common religion and a common transliteralization (Arabic), traders showed greater willingness to trust, and therefore invest, in one another.[53] Moreover, toward the 19th century, the Northern Nigeria based Sokoto Caliphate led by Usman dan Fodio exerted considerable effort in spreading Islam.[49]

Persia and the Caucasus

It used to be argued that Zoroastrianism quickly collapsed in the wake of the Islamic conquest of Persia due to its intimate ties to the Sassanid state structure.[7] Now however, more complex processes are considered, in light of the more protracted time frame attributed to the progression of the ancient Persian religion to a minority; a progression that is more contiguous with the trends of the late antiquity period.[7] These trends are the conversions from the state religion that had already plagued the Zoroastrian authorities that continued after the Arab conquest, coupled with the migration of Arab tribes into the region during an extended period of time that stretched well into the Abbasid reign.[7]

While there were cases such as the Sassanid army division at Hamra, that converted en masse before pivotal battles such as the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, conversion was fastest[54] in the urban areas where Arab forces were garrisoned slowly leading to Zoroastrianism becoming associated with rural areas.[7] Still at the end of the Umayyad period, the Muslim community was only a minority in the region.[7]

Through the Muslim conquest of Persia, in the 7th century, Islam spread as far as the North Caucasus, which parts of it (notably Dagestan) were part of the Sasanid domains.[55] In the coming centuries, relatively large parts of the Caucasus became Muslim, while the larger swaths of it would still remain pagan (paganism branches such as the Circassian Habze) as well as Christian (notably Armenia and Georgia), for centuries. By the 16th century, most of the people of what are nowadays Iran and Azerbaijan had adopted the Shia branch of Islam through the conversion policies of the Safavids.[56]

Islam was readily accepted by Zoroastrians who were employed in industrial and artisan positions because, according to Zoroastrian dogma, such occupations that involved defiling fire made them impure.[49] Moreover, Muslim missionaries did not encounter difficulty in explaining Islamic tenets to Zoroastrians, as there were many similarities between the faiths. According to Thomas Walker Arnold, for the Persian, he would meet Ahura Mazda and Ahriman under the names of Allah and Iblis.[49] At times, Muslim leaders in their effort to win converts encouraged attendance at Muslim prayer with promises of money and allowed the Quran to be recited in Persian instead of Arabic so that it would be intelligible to all.[49]

Robert Hoyland argues that the missionary efforts of the relatively small number of Arab conquerors in Persian lands led to "much interaction and assimilation" between rulers and ruled, and to descendants of the conquerors adapting the Persian language and Persian festivals and culture,[57] (Persian being the language of modern-day Iran, while Arabic is spoken by its neighbors to the west.)

Central Asia

A number of the inhabitants of Afghanistan accepted Islam through Umayyad missionary efforts, particularly under the reign of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and Umar ibn Abdul Aziz.[58] Later, starting from the 9th century, the Samanids, whose roots stemmed from Zoroastrian theocratic nobility, propagated Sunni Islam and Islamo-Persian culture deep into the heart of Central Asia. The population within its areas began firmly accepting Islam in significant numbers, notably in Taraz, now in modern-day Kazakhstan. The first complete translation of the Qur'an into Persian occurred during the reign of Samanids in the 9th century. According to historians, through the zealous missionary work of Samanid rulers, as many as 30,000 tents of Turks came to profess Islam and later under the Ghaznavids higher than 55,000 under the Hanafi school of thought.[59] After the Saffarids and Samanids, the Ghaznavids re-conquered Transoxania, and invaded the Indian subcontinent in the 11th century. This was followed by the powerful Ghurids and Timurids who further expanded the culture of Islam and the Timurid Renaissance, reaching until Bengal.

Turkey

Main articles: Arab-Byzantine Wars, Byzantine-Seljuq wars, Byzantine-Ottoman Wars.

Indian subcontinent

Islamic influence first came to be felt in the Indian subcontinent during the early 7th century with the advent of Arab traders. Arab traders used to visit the Malabar region, which was a link between them and the ports of South East Asia to trade even before Islam had been established in Arabia. According to Historians Elliot and Dowson in their book The History of India as told by its own Historians, the first ship bearing Muslim travelers was seen on the Indian coast as early as 630 CE. The first Indian mosque is thought to have been built in 629 CE, purportedly at the behest of an unknown Chera dynasty ruler, during the lifetime of Muhammad (c. 571–632) in Kodungallur, in district of Thrissur, Kerala by Malik Bin Deenar. In Malabar, Muslims are called Mappila.

In Bengal, Arab merchants helped found the Port of Chittagong. Early Sufi missionaries settled in the region as early as the 8th century.[60][61]

H. G. Rawlinson, in his book Ancient and Medieval History of India (ISBN 978-81-86050-79-8), claims the first Arab Muslims settled on the Indian coast in the last part of the 7th century. This fact is corroborated, by J. Sturrock in his South Kanara and Madras Districts Manuals,[62] and also by Haridas Bhattacharya in Cultural Heritage of India Vol. IV.[63]

The Arab merchants and traders became the carriers of the new religion and they propagated it wherever they went.[64] It was, however, the subsequent expansion of the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent over the next millennia that established Islam in the region.

Embedded within these lies the concept of Islam as a foreign imposition and Hinduism being natural condition of the natives who resisted, resulting in the failure of the project to Islamicize the Indian subcontinent is highly embroiled with the politics of the partition and communalism in India. Considerable controversy exists as to how conversion to Islam came about in the Indian subcontinent.[65] These are typically represented by the following schools of thought:[65]

- Conversion was a combination, initially by violence, threat or other pressure against the person.[65]

- As a socio-cultural process of diffusion and integration over an extended period of time into the sphere of the dominant Muslim civilization and global polity at large.[66]

- A related view is that conversions occurred for non-religious reasons of pragmatism and patronage such as social mobility among the Muslim ruling elite or for relief from taxes[65][66]

- Was a combination, initially made under duress followed by a genuine change of heart[65]

- That the bulk of Muslims are descendants of migrants from the Iranian plateau or Arabs.[66]

Muslim missionaries played a key role in the spread of Islam in India with some missionaries even assuming roles as merchants or traders. For example, in the 9th century, the Ismailis sent missionaries across Asia in all directions under various guises, often as traders, Sufis and merchants. Ismailis were instructed to speak to potential converts in their own language. Some Ismaili missionaries traveled to India and employed effort to make their religion acceptable to the Hindus. For instance, they represented Ali as the tenth avatar of Vishnu and wrote hymns as well as a mahdi purana in their effort to win converts.[49] At other times, converts were won in conjunction with the propagation efforts of rulers. According to Ibn Batuta, the Khaljis encouraged conversion to Islam by making it a custom to have the convert presented to the Sultan who would place a robe on the convert and award him with bracelets of gold.[68] During Delhi Sultanate's Ikhtiyar Uddin Bakhtiyar Khilji's control of the Bengal, Muslim missionaries in India achieved their greatest success, in terms of number of converts to Islam.[69]

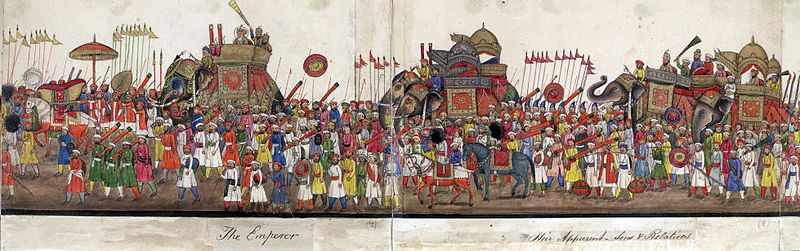

The Mughal Empire, founded by Babur, a direct descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan, was able to conquer almost the entirety of South Asia. Although religious tolerance was seen during the rule of emperor Akbar's, the reign under emperor Aurangzeb witnessed the full establishment of Islamic sharia and the re-introduction of Jizya (a special tax imposed upon non-Muslims) through the compilation of the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri.[70][71] The Mughals, already suffering a gradual decline in the early 18th century, was invaded by the Afsharid ruler Nader Shah.[72] The Mughal decline provided opportunities for the Maratha Empire, Sikh Empire, Mysore Kingdom, Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad and Nizams of Hyderabad to exercise control over large regions of the Indian subcontinent.[73] Eventually, after numerous wars sapped its strength, the Mughal Empire was broken into smaller powers like Shia Nawab of Bengal, the Nawab of Awadh, the Nizam of Hyderabad, and the Kingdom of Mysore, which became the major Asian economic and military power on the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed]

Southeast Asia

Even before Islam was established amongst Indonesian communities, Muslim sailors and traders had often visited the shores of modern Indonesia, most of these early sailors and merchants arrived from the Abbasid Caliphate's newly established ports of Basra and Debal, many of the earliest Muslim accounts of the region note the presence of animals such as orang-utans, rhinos and valuable spice trade commodities such as cloves, nutmeg, galangal and coconut.[74]

Islam came to the Southeast Asia, first by the way of Muslim traders along the main trade-route between Asia and the Far East, then was further spread by Sufi orders and finally consolidated by the expansion of the territories of converted rulers and their communities.[75] The first communities arose in Northern Sumatra (Aceh) and the Malacca's remained a stronghold of Islam from where it was propagated along the trade routes in the region.[75] There is no clear indication of when Islam first came to the region, the first Muslim gravestone markings year 1082.[76]

When Marco Polo visited the area in 1292 he noted that the urban port state of Perlak was Muslim,[76] Chinese sources record the presence of a Muslim delegation to the emperor from the Kingdom of Samudra (Pasai) in 1282,[75] other accounts provide instances of Muslim communities present in the Melayu Kingdom for the same time period while others record the presence of Muslim Chinese traders from provinces such as Fujian.[76] The spread of Islam generally followed the trade routes east through the primarily Buddhist region and a half century later in the Malacca's we see the first dynasty arise in the form of the Sultanate of Malacca at the far end of the Archipelago form by the conversion of one Parameswara Dewa Shah into a Muslim and the adoption of the name Muhammad Iskandar Shah[77] after his marriage to a daughter of the ruler of Pasai.[75][76]

In 1380, Sufi orders carried Islam from here on to Mindanao.[citation needed] Java was the seat of the primary kingdom of the region, the Majapahit Empire, which was ruled by a Hindu dynasty. As commerce grew in the region with the rest of the Muslim world, Islamic influence extended to the court even as the empires political power waned and so by the time Raja Kertawijaya converted in 1475 at the hands of Sufi Sheikh Rahmat, the Sultanate was already of a Muslim character. In Vietnam, the Cham people proselytized due to contact with traders and missionaries from Kelantan.

Another driving force for the change of the ruling class in the region was the concept among the increasing Muslim communities of the region when ruling dynasties to attempt to forge such ties of kinship by marriage.[citation needed] By the time the colonial powers and their missionaries arrived in the 17th century the region up to New Guinea was overwhelmingly Muslim with animist minorities.[76]

Flags of the Sultanates in the East Indies

- Sulu

- Deli

Inner Asia and Eastern Europe

In the mid 7th century AD, following the Muslim conquest of Persia, Islam penetrated into areas that would later become part of European Russia.[78] A centuries later example that can be counted amongst the earliest introductions of Islam into Eastern Europe came about through the work of an early 11th-century Muslim prisoner whom the Byzantines captured during one of their wars against Muslims. The Muslim prisoner was brought[by whom?] into the territory of the Pechenegs, where he taught and converted individuals to Islam.[79] Little is known about the timeline of the Islamization of Inner Asia and of the Turkic peoples who lay beyond the bounds of the caliphate. Around the 7th and 8th centuries some states of Turkic peoples existed - like the Turkic Khazar Khaganate (see Khazar-Arab Wars) and the Turkic Turgesh Khaganate, which fought against the caliphate in order to stop Arabization and Islamization in Asia. From the 9th century onwards, the Turks (at least individually, if not yet through adoption by their states) began to convert to Islam. Histories merely note the fact of pre-Mongol Central Asia's Islamization.[80] The Bulgars of the Volga (to whom the modern Volga Tatars trace their Islamic roots) adopted Islam by the 10th century.[80] under Almış. When the Franciscan friar William of Rubruck visited the encampment of Batu Khan of the Golden Horde, who had recently (in the 1240s) completed the Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria, he noted "I wonder what devil carried the law of Machomet there".[80]

Another contemporary institution identified as Muslim, the Qarakhanid dynasty of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, operated much further east,[80] established by Karluks who became Islamized after converting under Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan in the mid-10th century. However, the modern-day history of the Islamization of the region - or rather a conscious affiliation with Islam - dates to the reign of the ulus of the son of Genghis Khan, Jochi, who founded the Golden Horde,[81] which operated from the 1240s to 1502. Kazakhs, Uzbeks and some Muslim populations of the Russian Federation trace their Islamic roots to the Golden Horde[80] and while Berke Khan became the first Mongol monarch to officially adopt Islam and even to oppose his kinsman Hulagu Khan[80] in the defense of Jerusalem at the Battle of Ain Jalut (1263), only much later did the change became pivotal when the Mongols converted en masse[82] when a century later Uzbeg Khan (lived 1282–1341) converted - reportedly at the hands of the Sufi Saint Baba Tukles.[83]

Some of the Mongolian tribes became Islamized. Following the brutal Mongol invasion of Central Asia under Hulagu Khan and after the Battle of Baghdad (1258), Mongol rule extended across the breadth of almost all Muslim lands in Asia. The Mongols destroyed the caliphate and persecuted Islam, replacing it with Buddhism as the official state religion.[82] In 1295 however, the new Khan of the Ilkhanate, Ghazan, converted to Islam, and two decades later the Golden Horde under Uzbeg Khan (reigned 1313–1341) followed suit.[82] The Mongols had been religiously and culturally conquered; this absorption ushered in a new age of Mongol-Islamic synthesis[82] that shaped the further spread of Islam in central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

In the 1330s, the Mongol ruler of the Chagatai Khanate (in Central Asia) converted to Islam, causing the eastern part of his realm (called Moghulistan) to rebel.[84] However, during the next three centuries these Buddhist, Shamanistic and Christian Turkic and Mongol nomads of the Kazakh Steppe and Xinjiang would also convert at the hands of competing Sufi orders from both east and west of the Pamirs.[84] The Naqshbandis are the most prominent of these orders, especially in Kashgaria, where the western Chagatai Khan was also a disciple of the order.[84]

Muslims of Central Asian origin played a major role in the Mongol conquest of China. Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, a court official and general of Turkic origin who participated in the Mongol invasion of Southwest China, became Yuan Governor of Yunnan in 1274. A distinct Muslim community, the Panthays, was established in the region by the late 13th century.

Europe

Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Muslim general who led the Islamic conquest of Visigothic Hispania in 711-718 A.D. He is considered to be one of the most important military commanders in Iberian history. The name "Gibraltar" is the Spanish derivation of the Arabic name Jabal Tāriq (جبل طارق) (meaning "mountain of Tariq"), named after him.

There are accounts of the trade connections between the Muslims and the Rus, apparently Vikings who made their way towards the Black Sea through Central Russia. On his way to Volga Bulgaria, Ibn Fadlan brought detailed reports of the Rus, claiming that some had converted to Islam.

According to the historian Yaqut al-Hamawi, the Böszörmény (Izmaelita or Ismaili / Nizari) denomination of the Muslims who lived in the Kingdom of Hungary in the 10th to 13th centuries, were employed as mercenaries by the kings of Hungary.

Hispania / Al-Andalus

The history of Arab and Islamic rule in the Iberian peninsula is probably one of the most studied periods of European history. For centuries after the Arab conquest, European accounts of Arab rule in Iberia were negative. European points of view started changing with the Protestant Reformation, which resulted in new descriptions of the period of Islamic rule in Spain as a "golden age" (mostly as a reaction against Spain's militant Roman Catholicism after 1500)[citation needed].

The tide of Arab expansion after 630 rolled through North Africa up to Ceuta in present-day Morocco. Their arrival coincided with a period of political weakness in the three-centuries-old kingdom established in the Iberian peninsula by the Germanic Visigoths, who had taken over the region after seven centuries of Roman rule. Seizing the opportunity, an Arab-led (but mostly Berber) army invaded in 711, and by 720 had conquered the southern and central regions of the peninsula. The Arab expansion pushed over the mountains into southern France, and for a short period Arabs controlled the old Visigothic province of Septimania (centered on present-day Narbonne). The Arab Caliphate was pushed back by Charles Martel (Frankish Mayor of the Palace) at Poitiers, and Christian armies started pushing southwards over the mountains, until Charlemagne established in 801 the Spanish March (which stretched from Barcelona to present day Navarre).

A major development in the history of Muslim Spain was the dynastic change in 750 in the Arab Caliphate, when an Umayyad Prince escaped the slaughter of his family in Damascus, fled to Cordoba in Spain, and created a new Islamic state in the area. This was the start of a distinctly Spanish Muslim society, where large Christian and Jewish populations coexisted with an increasing percentage of Muslims. There are many stories of descendants of Visigothic chieftains and Roman counts whose families converted to Islam during this period. The at-first small Muslim elite continued to grow with converts, and with a few exceptions, rulers in Islamic Spain allowed Christians and Jews the right specified in the Koran to practice their own religions, though non-Muslims suffered from political and taxation inequities. The net result was, in those areas of Spain where Muslim rule lasted the longest, the creation of a society that was mostly Arabic-speaking because of the assimilation of native inhabitants, a process in some ways similar to the assimilation many years later of millions of immigrants to the United States into English-speaking culture. As the descendants of Visigoths and Hispano-Romans concentrated in the north of the peninsula, in the kingdoms of Asturias/Leon, Navarre and Aragon and started a long campaign known as the 'Reconquista' which started with the victory of the Christian armies in Covadonga in 722. Military campaigns continued without pause. In 1085 Alfonso VI of Castille took back Toledo. In 1212 the crucial Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa meant the recovery of the bulk of the peninsula for the Christian kingdoms. In 1238 James I of Aragon took Valencia. In 1236 the ancient Roman city of Cordoba was re-conquered by Ferdinand III of Castille and in 1248 the city of Seville. The famous medieval epic poem 'Cantar de Mio Cid' narrates the life and deeds of this hero during the Reconquista.

The Islamic state centered in Cordoba had ended up splintering into many smaller kingdoms (the so-called taifas). While Muslim Spain was fragmenting, the Christian kingdoms grew larger and stronger, and the balance of power shifted against the 'Taifa' kingdoms. The last Muslim kingdom of Granada in the south was finally taken in 1492 by Queen Isabelle of Castille and Ferdinand of Aragon. In 1499, the remaining Muslim inhabitants were ordered to convert or leave (at the same time the Jews were expelled). Poorer Muslims (Moriscos) who could not afford to leave ended up converting to Catholic Christianity and hiding their Muslim practices, hiding from the Spanish Inquisition, until their presence was finally extinguished.

Balkans

In Balkan history, historical writing on the topic of conversion to Islam was, and still is, a highly charged political issue. It is intrinsically linked to the issues of formation of national identities and rival territorial claims of the Balkan states. The generally accepted nationalist discourse of the current Balkan historiography defines all forms of Islamization as results of the Ottoman government's centrally organized policy of conversion or dawah. The truth is that Islamization in each Balkan country took place in the course of many centuries, and its nature and phase was determined not by the Ottoman government but by the specific conditions of each locality. Ottoman conquests were initially military and economic enterprises, and religious conversions were not their primary objective. True, the statements surrounding victories all celebrated the incorporation of territory into Muslim domains, but the actual Ottoman focus was on taxation and making the realms productive, and a religious campaign would have disrupted that economic objective.

Ottoman Islamic standards of toleration allowed for autonomous "nations" (millets) in the Empire, under their own personal law and under the rule of their own religious leaders. As a result, vast areas of the Balkans remained mostly Christian during the period of Ottoman domination. In fact, the Eastern Orthodox Churches had a higher position in the Ottoman Empire, mainly because the Patriarch resided in Istanbul and was an officer of the Ottoman Empire. In contrast, Roman Catholics, while tolerated, were suspected of loyalty to a foreign power (the Papacy). It is no surprise that the Roman Catholic areas of Bosnia, Kosovo and northern Albania, ended up with more substantial conversions to Islam. The defeat of the Ottomans in 1699 by the Austrians resulted in their loss of Hungary and present-day Croatia. The remaining Muslim converts in both elected to leave "lands of unbelief" and moved to territory still under the Ottomans. Around this point in time, new European ideas of romantic nationalism started to seep into the Empire, and provided the intellectual foundation for new nationalistic ideologies and the reinforcement of the self-image of many Christian groups as subjugated peoples.

As a rule, the Ottomans did not require followers of Greek Orthodoxy to become Muslims, although many did so in order to avert the socioeconomic hardships of Ottoman rule.[85] One by one, the Balkan nationalities asserted their independence from the Empire, and frequently the presence of members of the same ethnicity who had converted to Islam presented a problem from the point of view of the now dominant new national ideology, which narrowly defined the nation as members of the local dominant Orthodox Christian denomination.[86] Some Muslims in the Balkans chose to leave, while many others were forcefully expelled to what was left of the Ottoman Empire.[86] This demographic transition can be illustrated by the decrease in the number of mosques in Belgrade, from over 70 in 1750 (before Serbian independence in 1815), to only three in 1850.

Immigration

Since the 1960s, many Muslims have migrated to Western Europe. They have arrived as immigrants, guest workers, asylum seekers or as part of family reunification. As a result, the Muslim population in Europe has steadily risen.

A Pew Forum study, published in January 2011, forecast an increase of the proportion of Muslims in the European population from 6% in 2010 to 8% in 2030.[87]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Also spelled Islamisation; see spelling differences.

Citations

- ^ Polk, William R. (2018). "The Caliphate and the Conquests". Crusade and Jihad: The Thousand-Year War Between the Muslim World and the Global North. The Henry L. Stimson Lectures Series. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 21–30. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1bvnfdq.7. ISBN 978-0-300-22290-6. JSTOR j.ctv1bvnfdq.7. LCCN 2017942543.

- ^ van Ess, Josef (2017). "Setting the Seal on Prophecy". Theology and Society in the Second and Third Centuries of the Hijra, Volume 1: A History of Religious Thought in Early Islam. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East. Vol. 116/1. Translated by O'Kane, John. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 3–7. doi:10.1163/9789004323384_002. ISBN 978-90-04-32338-4. ISSN 0169-9423.

- ^ Pakatchi, Ahmad; Ahmadi, Abuzar (2017). "Caliphate". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica. Translated by Asatryan, Mushegh. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_05000066. ISSN 1875-9823.

- ^ a b Lewis, Bernard (1995). "Part III: The Dawn and Noon of Islam – Origins". The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. New York: Scribner. pp. 51–58. ISBN 9780684832807. OCLC 34190629.

- ^ Hassan, M. Kabir (30 December 2016). Handbook of Empirical Research on Islam and Economic Life. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78471-073-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gibbon, ci, ed. Bury, London, 1898, V, 436

- ^ a b c d e f Berkey, pg. 101-102

- ^ a b Tramontana, Felicita (2014). "III. Conversion to Islam in the villages of Dayr Abān and Ṣūbā". Passages of Faith: Conversion in Palestinian villages (17th century) (1 ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 69. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc16s06.8. ISBN 978-3-447-10135-6. JSTOR j.ctvc16s06.

- ^ Formichi, Chiara (2020). Islam and Asia: A History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–102. ISBN 978-1-107-10612-3.

- ^ "Executive Summary". The Future of the Global Muslim Population. Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Table: Muslim Population by Country | Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project". Features.pewforum.org. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Hallaq, Wael (2009). An introduction to Islamic law. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-67873-5.

- ^ "Religion and Public Life". Pew Research Center. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "The Changing Global Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Main Factors Driving Population Growth". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Burke, Daniel (4 April 2015). "The world's fastest-growing religion is ..." CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Lippman, Thomas W. (7 April 2008). "No God But God". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

Islam is the youngest, the fastest growing, and in many ways the least complicated of the world's great monotheistic faiths. It is based on its own holy book, but it is also a direct descendant of Judaism and Christianity, incorporating some of the teachings of those religions—modifying some and rejecting others.

- ^ "Islamicization". The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Robinson, David, ed. (2004), "The Islamization of Africa", Muslim Societies in African History, New Approaches to African History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–41, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511811746.004, ISBN 978-0-521-82627-3, retrieved 13 November 2022

- ^ Kennedy, Charles (1996). "Introduction". Islamization of Laws and Economy, Case Studies on Pakistan. Anis Ahmad, Author of introduction. Institute of Policy Studies, The Islamic Foundation. p. 19.

- ^ Lindley-Highfield, M. (2008) '"Muslimization", Mission and Modernity in Morelos: the problem of a combined hotel and prayer hall for the Muslims of Mexico'. Tourism Culture & Communication, vol. 8, no. 2, 85–96.

- ^ a b c d Goddard, pg.126-131

- ^ Hourani, pg.22-24

- ^ a b c d e f Lapidus, 200-201

- ^ a b c Hoyland, In God's Path, 2015: p. 207

- ^ a b c Hourani, pg.41-48

- ^ a b Lapidus, 271.

- ^ לוי-רובין, מילכה (2006). שטרן, אפרים; אשל, חנן (eds.). ספר השומרונים [Book of the Samaritans; The Continuation of the Samaritan Chronicle of Abu l-Fath] (in Hebrew) (2 ed.). ירושלים: יד יצחק בן צבי, רשות העתיקות, המנהל האזרחי ליהודה ושומרון: קצין מטה לארכיאולוגיה. pp. 562–586. ISBN 965-217-202-2.

- ^ Hourani, pg.54

- ^ Hourani, pg.221,222

- ^ Hakan Ozoglu (24 June 2011). From Caliphate to Secular State: Power Struggle in the Early Turkish Republic. ABC-CLIO. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-313-37957-4. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Lapidus, p. 823

- ^ a b c Lapidus, p. 828–30

- ^ Marcia Hermansen (2014). "Conversion to Islam in Theological and Historical Perspectives". In Lewis R. Rambo and Charles E. Farhadian (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press. p. 632.

The process of "Islamization" was a complex and creative fusion of Islamic practices and doctrines with local customs that were considered to be sound from the perspective of developing Islamic jurisprudence. As historian Richard Bulliet has demonstrated based on the evidence of early biographical compendia, in most cases this process took centuries, so that the stereotype of Islam being initially spread by the "sword" and by forced conversions is a false representation of this complex phenomenon

- ^ a b c Fred Astren pg.33-35

- ^ a b c Tobin 113-115

- ^ Donald E. Wagner. Dying in the Land of Promise: Palestine and Palestinian Christianity from Pentecost to 2000

- ^ a b c "Jerusalem". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1910.

- ^ Marcus, Jacob Rader (March 2000). The Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, 315-1791 (Revised ed.). Hebrew Union College Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-87820-217-1.

- ^ Gibbon, ci, ed. Bury, London, 1898, V, 436

- ^ a b The Genius of Arab Civilization. MIT Press. January 1983. ISBN 978-0-262-08136-8. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Hoyland, In God's Path, 2015: p. 161

- ^ "Byzantine Empire - The successors of Heraclius: Islam and the Bulgars". Britannica. 2007.

- ^ Hoyland, In God's Path, 2015: p. 97

- ^ Abun-Nasr, Jamil M.; Abun-Nasr, Jamil Mirʻi Abun-Nasr (20 August 1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002). Pilgrimage. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Islamic world - Berbers". Britannica. 2007.

- ^ "Western North African Christianity: A History of the Christian Church in Western North Africa". Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp.125-258

- ^ "A Country Study: Somalia from The Library of Congress". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b "The Return of Religion: Currents of Resurgence, Convergence, and Divergence- The Cresset (Trinity 2009)". Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Christian Number-Crunching reveals impressive growth". Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Paul Stoller, "Money Has No Smell: The Africanization of New York City," Chicago: University of Chicago Press". Archived from the original on 23 December 2007.

- ^ Raza, Mohammad (21 May 2023). "Who wrote book Theologus Autodidactus ?| How was the Islamic golden age | How Islam spread ? |". Think With Wajahat. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Shireen Hunter; Jeffrey L. Thomas; Alexander Melikishvili; et al. (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. p. 3.

(..) It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin (5 July 2004). The Caspian: politics, energy and security, By Shirin Akiner, pg.158. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-64167-5. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Hoyland, In God's Path, 2015: p. 206

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith, By Thomas Walker Arnold, p. 183

- ^ The History of Iran By Elton L. Daniel, pg. 74

- ^ "New Age | the Outspoken Daily". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Siddiq, Mohammad Yusuf (2015). Epigraphy and Islamic Culture: Inscriptions of the Early Muslim Rulers of Bengal (1205–1494). Routledge. pp. 27–33. ISBN 978-1-317-58745-3.

- ^ Sturrock, J., South Canara and Madras District Manual (2 vols., Madras, 1894–1895)

- ^ ISBN 978-81-85843-05-6 Cultural Heritage of India Vol. IV

- ^ "Mujeeb Jaihoon". jaihoon.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e der Veer, pg 27–29

- ^ a b c Eaton, "5. Mass Conversion to Islam: Theories and Protagonists"

- ^ Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2A, The Indian Sub-Continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, p. 212

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 227–228

- ^ Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-95036-0.

- ^ Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-78347-572-8.

- ^ "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ Ian Copland; Ian Mabbett; Asim Roy; et al. (2012). A History of State and Religion in India. Routledge. p. 161.

- ^ Sinbad the Sailor

- ^ a b c d P. M. ( Peter Malcolm) Holt, Bernard Lewis, "The Cambridge History of Islam", Cambridge University Press, pr 21, 1977, ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8 pg.123-125

- ^ a b c d e Colin Brown, A Short History of Indonesia, Allen & Unwin, July 1, 2003 ISBN 978-1-86508-838-9 pg.31-33

- ^ He changes his name to reflect his new religion.

- ^ Shireen Hunter; Jeffrey L. Thomas; Alexander Melikishvili; et al. (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. p. 3.

(..) It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

- ^ Arnold, Sir Thomas Walker (1896). The Preaching of Islam. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Devin pg. 19

- ^ Devin pg 67-69

- ^ a b c d Daniel W. Brown, " New Introduction to Islam", Blackwell Publishing, August 1, 2003, ISBN 978-0-631-21604-9 pg. 185-187

- ^ Devin 160.

- ^ a b c S. Frederick (EDT) Starr, "Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland", M.E. Sharpe, April 1, 2004 ISBN 978-0-7656-1317-2 pg. 46-48

- ^ "PontosWorld". pontosworld.com.

- ^ a b Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-230-11908-6.

- ^ "Nothing found for The Future Of The Global Muslim Population Aspx?print=true". Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

Sources

- Astren, Fred. Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding, Univ of South Carolina Press, 2004 (ISBN 978-1-57003-518-0).

- Berkey, Jonathan. The Formation of Islam, Cambridge University Press, 2003 (ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3).

- Devin De Weese, Devin A, Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde, Penn State University Press, 1994 (ISBN 978-0-271-01073-1).

- Eaton, Richard M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993.Online version last accessed on 1 May 1948

- Goddard, Hugh Goddard, Christians and Muslims: from double standards to mutual understanding, Routledge (UK), 1995 (ISBN 978-0-7007-0364-7).

- Hourani, Albert, 2002, A History of the Arab Peoples, Faber & Faber (ISBN 978-0-571-21591-1).

- Kayadibi, Saim. Ottoman Connections to the Malay World: Islam, Law and Society, Kuala Lumpur: The Other Press, 2011 (ISBN 978-983-9541-77-9).

- Lapidus, Ira M. 2002, A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Savage, Timothy M. "Europe and Islam: Crescent Waxing, Cultures Clashing" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Quarterly, Summer 2004.

- Schuon, Frithjof, Understanding Islam, World Wisdom Books, 2013.

- Siebers, Tobin. "Religion and the Authority of the Past", University of Michigan Press, 1993 (ISBN 978-0-472-08259-9).

- Soares de Azevedo, Mateus. Men of a Single Book: Fundamentalism in Islam and Christianity, World Wisdom, 2011.

- Stoddart, William, What does Islam mean in today's world?, World Wisdom Books, 2011.

- Stoller, Paul. Money Has No Smell: The Africanization of New York City, (University of Chicago Press, 2001) (ISBN 978-0-226-77529-6).

- van der Veer, Peter. Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India, University of California Press, 1994 (ISBN 978-0-520-08256-4).

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2015). In God's Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford University Press.