Islamic garden

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

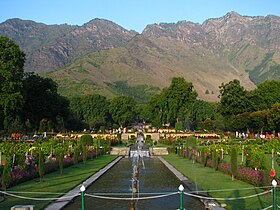

An Islamic garden is generally an expressive estate of land that includes themes of water and shade. Their most identifiable architectural design reflects the charbagh (or chahār bāgh) quadrilateral layout with four smaller gardens divided by walkways or flowing water. Unlike English gardens, which are often designed for walking, Islamic gardens are intended for rest, reflection, and contemplation. A major focus of the Islamic gardens was to provide a sensory experience, which was accomplished through the use of water and aromatic plants.

Before Islam had expanded to other climates, these gardens were historically used to provide respite from a hot and arid environment. They encompassed a wide variety of forms and purposes which no longer exist. The Qur'an has many references to gardens and states that gardens are used as an earthly analogue for the life in paradise which is promised to believers:

Allah has promised to the believing men and the believing women gardens, beneath which rivers flow, to abide in them, and goodly dwellings in gardens of perpetual abode; and best of all is Allah's goodly pleasure; that is the grand achievement. – Qur'an 9.72

Along with the popular paradisiacal interpretation of gardens, there are several other non-pious associations with Islamic gardens including wealth, power, territory, pleasure, hunting, leisure, love, and time and space. These other associations provide more symbolism in the manner of serene thoughts and reflection and are associated with a scholarly sense.

While many Islamic gardens no longer exist, scholars have inferred much about them from Arabic and Persian literature on the subject. Numerous formal Islamic gardens have survived in a wide zone extending from Spain and Morocco in the west to India in the east.[1] Historians disagree as to which gardens ought to be considered part of the Islamic garden tradition, which has influenced three continents over several centuries.

Architectural design and influences

After the Arab invasions of the 7th century CE, the traditional design of the Persian garden was used in many Islamic gardens. Persian gardens were traditionally enclosed by walls and the Persian word for an enclosed space is pairi-daeza, leading to the paradise garden.[2] Hellenistic influences are also apparent in their design, as seen in the use of straight lines in a few garden plans that are also blended with Sassanid ornamental plantations and fountains.[3]

One of the most identifiable garden designs, known as the charbagh (or chahār bāgh), consists of four quadrants most commonly divided by either water channels or walkways, that took on many forms.[4] One of these variations included sunken quadrants with planted trees filling them, so that they would be level to the viewer.[4] Another variation is a courtyard at the center intersection, with pools built either in the courtyard or surrounding the courtyard.[4] While the charbagh gardens are the most identified gardens, very few were actually built, possibly due to their high costs or because they belonged to the higher class, who had the capabilities to ensure their survival.[4] Notable examples of the charbagh include the former Bulkawara Palace in Samarra, Iraq,[5] and Madinat al-Zahra near Córdoba, Spain.[6]

An interpretation of the charbagh design is conveyed as a metaphor for a "whirling wheel of time" that challenges time and change.[7] This idea of cyclical time places man at the center of this wheel or space and reinforces perpetual renewal and the idea that the garden represents the antithesis of deterioration.[7] The enclosed garden forms a space that is permanent, a space where time does not decay the elements within the walls, representing an unworldly domain.[7] At the center of the cycle of time is the human being who, after being released, eventually reaches eternity.[7]

Aside from gardens typically found in palaces, they also found their way into other locations. The Great Mosque of Córdoba contains a continuously planted garden in which rows of fruit trees, similar to an orchard, were planted in the courtyard.[4] This garden was irrigated by a nearby aqueduct and served to provide shade and possibly fruit for the mosque's caretaker.[4] Another type of garden design includes stepped terraces, in which water flows through a central axis, creating a trickling sound and animation effect with each step, which could also be used to power water jets.[4] Examples of the stepped terrace gardens include the Shālamār Bāgh, the Bāgh-i Bābur, and Madinat al-Zahra.[4]

Elements

Islamic gardens present a variety of devices that contribute to the stimulation of several senses and the mind, to enhance a person's experience within the garden. These devices include the manipulation of water and the use of aromatic plants.[8]

Arabic and Persian literature reflect how people historically interacted with Islamic gardens. The gardens' worldly embodiment of paradise provided the space for poets to contemplate the nature and beauty of life. Water is the most prevalent motif in Islamic garden poetry, as poets render water as semi-precious stones and features of their beloved women or men.[9] Poets also engaged multiple sensations to interpret the dematerialized nature of the garden. Sounds, sights, and scents in the garden led poets to transcend the dry climate in desert-like locations.[10] Classical literature and poetry on the subject allow scholars to investigate the cultural significance of water and plants, which embody religious, symbolic, and practical qualities.

Water

Water was an integral part of the landscape architecture and served many sensory functions, such as a desire for interaction, illusionary reflections, and animation of still objects, thereby stimulating visual, auditory and somatosensory senses. The centrally placed pools and fountains in Islamic gardens remind visitors of the essence of water in the Islamic world.

Islam emerged in the desert, and the thirst and gratitude for water are embedded in its nature. In the Qur'an, rivers are the primary constituents of the paradise, and references to rain and fountains abound. Water is the materia prima of the Islamic world, as stated in the Qur'an 31:30: "God preferred water over any other created thing and made it the basis of creation, as He said: 'And We made every living thing of water'." Water embodies the virtues God expects from His subjects. "Then the water was told, 'Be still'. And it was still, awaiting God's command. This is implied water, which contains neither impurity nor foam" (Tales of the Prophets, al-Kisa'). Examining their reflections in the water allows the faithful to integrate the water's stillness and purity, and the religious implication of water sets the undertone for the experience of being in an Islamic garden.[10]

Based on the spiritual experience, water serves as the means of physical and emotional cleansing and refreshment. Due to the hot and arid conditions where gardens were often built, water was used as a way to refresh, cleanse, and cool an exhausted visitor. Therefore, many people would come to the gardens solely to interact with the water.[2]

Reflecting pools were strategically placed to reflect the building structures, interconnecting the exterior and interior spaces.[8] The reflection created an illusion that enlarged the building and doubled the effect of solemnity and formality. The effect of rippling water from jets and shimmering sunlight further emphasized the reflection.[8] In general, mirroring the surrounding structures combined with the vegetation and the sky creates a visual effect that expands the enclosed space of a garden. Given the water's direct connection to paradise, its illusionary effects contribute to a visitor's spiritual experience.

Another use of water was to provide kinetic motion and sound to the stillness of a walled garden,[8] enlivening the imposing atmosphere. Fountains, called salsabil fountains for "the fountain in the paradise" in Arabic, are prevalent in medieval Islamic palaces and residences. Unlike the pools that manifest stillness, these structures demonstrate the movement of water, yet celebrate the solidity of water as it runs through narrow channels extending from the basin.[10]

In the Alhambra Palace, around the rim of the basin of the Fountain of the Lions, the admiration for the water's virtue is inscribed: "Silver melting which flows between jewels, one like the other in beauty, white in purity; a running stream evokes the illusion of a solid substance; for the eyes, so that we wonder which one is fluid. Don't you see that it is the water that is running over the rim of the fountain, whereas it is the structure that offers channels for the water flow."[9] By rendering the streams of water melting silver, the poem implies that though the fountain creates dynamics, the water flowing in the narrow channels allow the structure to blend into the solemn architectural style as opposed to disrupting the harmony. Many Nasrid palaces included a sculpture in their garden in which a jet of water would flow out of the structure's mouth, adding motion and a "roaring sound" of water to the garden.[8]

As the central component of Islamic architecture, water incorporates the religious implications and contributes to the spiritual, bodily and emotional experience that visitors could hardly acquire from the outside world.

Sensory plants

Irrigation and fertile soil were used to support a botanical variety which could not otherwise exist in a dry climate.[11] Many of the extant gardens do not contain the same vegetation as when they were first created, due to the lack of botanical accuracy in written texts. Historical texts tended to focus on the sensory experience, rather than details of the agriculture.[12] There is, however, record of various fruit-bearing trees and flowers that contributed to the aromatic aspect of the garden, such as cherries, peaches, almonds, jasmine, roses, narcissi, violets, and lilies.[2] According to the medico-botanical literature, many plants in the Islamic garden produce therapeutic and erotic aromatics.

Muslim scientist al-Ghazzi, who believed in the healing powers of nature, experimented with medicinal plants and wrote extensively on scented plants.[13] A garden retreat was often a "royal" prescription for treating headaches and fevers. The patient was advised to "remain in cool areas, surrounded by plants that have cooling effects such as sandalwood trees and camphor trees."[14]

Yunani medicine explains the role of scent as a mood booster, describing scent as "the food of the spirit". Scent enhances one's perceptions,[15] stirs memories, and makes the experience of visiting the garden more personal and intimate. Islamic medico-botanical literature suggests the erotic nature of some aromatic plants, and medieval Muslim poets note the role of scents in love games. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah reflects the scents worn by lovers to attract each other, and the presence of aromatic bouquets that provides sensual pleasures in garden spaces.[16]

Exotic plants were also sought by royalty for their exclusivity as status symbols, to signify the power and wealth of the country.[17] Examples of exotic plants found in royal gardens include pomegranates, Dunaqāl figs, a variety of pears, bananas, sugar cane and apples, which provided a rare taste.[17] By the tenth century, the royal gardens of the Umayyads at Cordova were at the forefront of botanical gardens, experimenting with seeds, cuttings, and roots brought from the outermost reaches of the known world.[18]

Dematerialization

The wide variety and forms of devices used in structuring the gardens provide inconsistent experiences for the viewer, and contribute to the garden's dematerialization.[clarification needed][8] The irregular flow of water and the angles of sunlight were the primary tools used to create a mysterious experience in the garden.[8] Many aspects of gardens were also introduced inside buildings and structures to contribute to the building's dematerialization. Water channels were often drawn into rooms that overlooked lush gardens and agriculture so that gardens and architecture would be intertwined and indistinguishable, deemphasizing a human's role in the creation of the structure.[19]

Symbolism

Paradise

Islamic gardens carry several associations of purpose beyond their common religious symbolism.[20] Most Islamic gardens are typically thought to represent paradise. In particular, gardens that encompassed a mausoleum or tomb were intended to evoke the literal paradise of the afterlife.[21]

For the gardens that were intended to represent paradise, there were common themes of life and death present, such as flowers that would bloom and die, representing a human's life.[19] Along with flowers, other agriculture such as fruit trees were included in gardens that surrounded mausoleums.[22] These fruit trees, along with areas of shade and cooling water, were added because it was believed that the souls of the deceased could enjoy them in the afterlife.[22] Fountains, often found in the center of the gardens, were used to represent paradise and were most commonly octagonal, which is geometrically inclusive of a square and a circle.[2] In this octagonal design, the square was representative of the earth, while the circle represented heaven, therefore its geometric design was intended to represent the gates of heaven; the transition between earth and heaven.[2] The color green was also a very prominent tool in this religious symbolism, as green is the color of Islam, and a majority of the foliage, aside from flowers, expressed this color.[2]

Religious references

Gardens are mentioned in the Qur'an to represent a vision of paradise. It states that believers will dwell in "gardens, beneath which rivers flow" (Qur'an 9:72). The Qur'an mentions paradise as containing four rivers: honey, wine, water, and milk; this has led to a common misinterpreted association of the charbagh design's four axial water channels solely with paradise.[23]

Images of paradise abound in poetry. The ancient king Iram, who attempted to rival paradise by building the "Garden of Iram" in his kingdom, captured the imagination of poets in the Islamic world.[relevant?] The description of gardens in poetry provides the archetypal garden of paradise. Pre-Islamic and Umayyad cultures imagined serene and rich gardens of paradise that provided an oasis in the arid environment in which they often lived.[6] A Persian garden, based on the Zoroastrian myth, is a prototype of the garden of water and plants. Water is also an essential aspect of this paradise for the righteous.[6] The water in the garden represents Kausar, the sacred lake in paradise, and only the righteous deserve to drink. Water represents God's benevolence to his people, a necessity for survival.[6] Rain and water are also closely associated with God's mercy in the Qur'an.[2] Conversely, water can be seen as a punishment from God through floods and other natural disasters.[6]

The use of a garden as a metaphor is well established in Deccani literature, with an unkempt garden representing a world in disarray and a "garden of love" suggesting fulfilment and harmony.[24] The Deccani poem Gulshan-i 'Ishq ("Rose Garden of Love"), written by Nusrati in 1657, describes a succession of natural scenes,[24] culminating in a rose garden that serves as a poetic metaphor for spiritual and romantic union.[25]

The four squares of the charbagh refer to the Islamic aspect of universe: that the universe is composed of four different parts. The four dividing water channels symbolize the four rivers in paradise. The gardener is the earthly reflection of Rizvan, the gardener of Paradise. Of the trees in Islamic gardens, "chinar" refers to the Ṭūbā tree that grows in heaven. The image of the Tuba tree is also commonly found on the mosaic and mural of Islamic architecture. In Zoroastrian myth, Chinar is the holy tree which is brought to Earth from heaven by the prophet Zoroaster.

Status symbols

Islamic gardens were often used to convey a sense of power and wealth among its patrons. The magnificent size of palace gardens directly showed an individual's financial capabilities and sovereignty while overwhelming their audiences.[6] The palaces and gardens built in Samarra, Iraq, were massive in size, demonstrating the magnificence of the Abbasid Caliphate.[6]

To convey royal power, parallels are implied to connect the "garden of paradise" and "garden of the king". The ability to regulate water demonstrated the ruler's power and wealth associated with irrigation. The ruling caliph had control over the water supply, which was necessary for gardens to flourish, making it understood that owning a large functioning garden required a great deal of power.[6] Rulers and wealthy elite often entertained their guests on their garden properties near water, demonstrating the luxury that came with such an abundance of water.[6] The light reflected by water was believed to be a blessing upon the ruler's reign.[6] In addition, the well-divided garden implies the ruler's mastery over their environment.

Several palace gardens, including Hayr al-Wuhush in Samarra, Iraq, were used as game preserves and places to hunt.[26] The sheer size of the hunting enclosures reinforced the power and wealth of the caliph.[6] A major idea of the 'princely cycle' was hunting, in which it was noble to partake in the activity and showed greatness.[26]

Variations of design

Many of the gardens of Islamic civilization no longer exist today. While most extant gardens retain their forms, they had not been continually tended and the original plantings have been replaced with contemporary plants.[27] A transient form of architectural art, gardens fluctuate due to the climate and the resources available for their care. The most affluent gardens required considerable resources by design, and their upkeep could not be maintained across eras. A lack of botanical accuracy in the historical record has made it impossible to properly restore the agriculture to its original state.[12]

There is debate among historians as to which gardens ought to be considered part of the Islamic garden tradition, since it spans Asia, Europe, and Africa over centuries.[28]

Umayyad gardens

Al-Ruṣāfa, near the village of the same name in present-day northern Syria, was a palace with an enclosed garden at the country estate of Umayyad caliph Hishām I. It had a stone pavilion in the center with arcades surrounding the pavilion. It is believed to be the earliest example of a formal charbagh design.[12]

Abbasid gardens

The Dar al-Khilafa palace was built in 836 at Samarra, at the order of the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tasim. The palace can be entered through the Bab-al'Amma portal. This portal's second story allowed people to gain an entire view of the nearby landscapes, including a large pool, pavilions and gardens. An esplanade was also included with gardens and fountains. A polo ground was incorporated along the facade of the palace, as well as racetrack and hunting preserves.[29]

Gardens in al-Andalus and the Maghreb

The terraced gardens of Madinat al-Zahra in al-Andalus, built in the 10th century under Abd ar-Rahman III and ruined in the 11th century, are the earliest well-documented examples of a symmetrically-divided enclosed garden in the western Islamic world and among the earliest examples in the Islamic world more generally.[30][31] They are also the earliest example in the region to combine this with a system of terraces.[31] This type of Andalusi garden probably drew its origins from the Persian chahar bagh garden in the east and was imported to the west by Umayyad patrons.[30][31]: 69–70 An older country estate known as al-Qasr ar-Rusafa, built by Abd ar-Rahman I near Cordoba in 777, has not been fully studied but probably also featured gardens and pavilions with elevated views, which suggests that this garden tradition was adopted very early by the Umayyad emirs of Al-Andalus.[31] Symmetrically-divided courtyard gardens, later known as a riyad (or riad), would go on to become a typical feature of western Islamic architecture in the Maghreb and al-Andalus, including later Andalusi palaces such as the Aljaferia and the Alhambra.[32][33][30]

In present-day Algeria, the Qal'at Beni Hammad ("Citadel of the Beni Hammad") was the fortified capital city built by the Hammadid dynasty in the early 11th century. Its ruins have remained uninhabited for 800 years but have been investigated by archeologists. Dar al-Bahr, the Lake Palace, is situated on the southern end of the city. During its time, it was remarked upon by visitors for the nautical spectacles enacted in its large pool. Surrounding the pool and the palace were terraces, courtyards and gardens. Little is known of the details of these gardens, other than the lion motifs carved in their stone fountains.[34] The earliest known example of a riyad garden in the western Maghreb (present-day Morocco) was the palace built by the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf in Marrakesh in the early 12th century, although it is only known from archeological excavations. Riyad gardens continued to proliferate after this period, especially in Marrakesh. Notably, the late 16th-century Saadi sultan Ahmad al-Mansur built very large riyad palaces including the monumental reception palace known as El Badi and a separate leisure palace inside the Agdal Gardens.[32][30][35]

In al-Andalus, the Generalife of Granada, built by the Nasrid dynasty under Muhammad II or Muhammad III on a hill across from Alhambra, is another famous example.[36][37] The palace contains many gardens with fountains, pavilions providing views of the landscape, and shallow-rooted plants. Although it has been modified and replanted over the centuries, two major elements have been preserved from the original design: the Acequia ("canal") Court and the "water stairway" that went to the upper level of the estate.[37]

Mughal gardens

The Mughal gardens of present-day India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, are derived from Islamic gardens with nomadic Turkish-Mongolian influences such as tents, carpets and canopies. Mughal symbols, numerology and zodiacal references were often juxtaposed with Quranic references, while the geometric design was often more rigidly formal. Due to a lack of swift-running rivers, water-lifting devices were frequently needed for irrigation. Early Mughal gardens were built as fortresses, like the Gardens of Babur, with designs later shifting to riverfront gardens like the Taj Mahal.[38][39][40][41]

Ottoman gardens

In the Ottoman era, Ottoman sultans and elites built various palaces, leisure kiosks, and garden estates along the shores of the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara around Constantinople (Istanbul).[42] Unlike Mughal and Safavid gardens where strict geometry and symmetry was observed, the royal gardens in Topkapı Palace (the main residence of the sultans for much of the period) were laid out according to natural topography and emphasized naturalism over geometry. Some were organized as formal gardens whereas others took the appearance of semi-natural parks. Some sections consisted of formal parterres that were then placed inside larger informal garden areas.[42] One documented exception to this general Ottoman trend was the Karabali Garden, laid out in the early 16th century in Kabataş, which had four symmetrical quadrants divided by axial paths.[42] Sultan Suleyman (r. 1520–1566) was noted as a lover of gardens and employed some 2,500 gardeners to tend to roses, cypresses, and other flowering plants.[42] In the Tulip Period, during the reign of Sultan Ahmet III (r. 1703-1730), flowerbeds of tulips were planted.[42] The Topkapı-style tradition of a sprawling palace with multiple pavilions amidst garden was renewed again in the late 19th century when Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876–1909) moved his residence to the new Yıldız Palace, which is set inside a large park area on the slopes overlooking the Bosphorus.[42]

Funerary gardens were often also attached to large mosques. These cemeteries were not only planted with trees and flowers, but the graves themselves may have been imagined as miniature gardens, with plots laid out for planting and some tombstones even having holes to anchor vines.[42] The cemetery behind the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul is one such example, among others.[42]

Evliya Çelebi's 17th century travel book Seyahatnâme contains descriptions of paradise gardens around the towns of Berat and Elbasan, in present-day Albania. According to Robert Elsie, an expert on Albanian culture, very few traces of the refined oriental culture of the Ottoman era remain here today. Çelebi describes the town of Berat as an open town with appealing homes, gardens, and fountains, spread over seven green hills. Çelebi similarly describes the town of Elbasan as having luxurious homes with vineyards, paradise gardens and well-appointed parks, each with a pool and fountain of pure water.[43]

Persian gardens

The building of Chehel Sotoun, Isfahan was completed by Safavid Shah 'Abbas II at 1647, with a reception hall and a fifteen-acre garden. It was located among other royal gardens between the Isfahan palace and the chahar bagh Avenue. Three walkways lead to the reception hall in the garden, and a rectangular pool within the garden reflects the image of the hall in water.[44]

Another example of Persian gardens is Shah-Gul Garden in Tabriz also called the "Royal Basin", built by one of Iran's wealthy families or ruling class in 1785 during the Qajar period, when Tabriz became a popular location for country estates. It is centered around a square lake of about 11 acres. On the south side of the lake, fruit trees surround it, and seven risen stepped terraces originate from these rows of trees. A modern pavilion was built on an eighteenth-century platform at the center of the lake. This garden is one of the few gardens still surviving in Tabriz.[27]

Modern gardens

The Al-Azhar Park in Cairo was opened in 2005 at the Darassa Hill. According to D. Fairchild Ruggles, it is "a magnificent site that evokes historic Islamic gardens in its powerful geometries, sunken garden beds, Mamluk-style polychromatic stonework, axial water channels, and playing fountains, all interpreted in a subdued modern design." As a modern park, it was built as part of a larger urban scheme, designed to serve its nearby communities.[45]

Flora

Common plants found in Islamic gardens include:[46]

- Hollyhock (Althaea)

- Pineapple (Ananas comosus)

- Jackfruit (Artocarpus integrifolia)

- Quince (Cydonia oblonga)

- Hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa sinensis)

- Hyacinth (Hyacinthus)

- Iris (Iris)

- Jasmine (Jasminum auriculatum)

- Apple (Malus)

- Oleander (Nerium)

- Lotus (Nymphaea)

- Date palm (Phoenix dactilifera)

- Apricot (Prunus armenaica)

- Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

- Rose (Rosa glandifulera)

See also

- Mughal gardens: An extension of the Islamic garden tradition during Mughal rule in Indian subcontinent

- Persian gardens: A garden tradition closely related to the Islamic garden

- Al-Masjid an-Nabawi § Rawdah ash-Sharifah: garden of the Prophet's Mosque

References

- ^ Latiff, Zainab; Ismail, Sumarni (March 10, 2016). "The Islamic Garden: Its Origin And Significance" (PDF). Research Journal of Fisheries and Hydrobiology (1816–9112).

- ^ a b c d e f g Clark, Emma. "The Symbolism of the Islamic Garden "Islamic Arts and Architecture". Islamic Arts and Architecture.

- ^ Marie-Luise Gothein, A History of Garden Art, Diederichs, 1914, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ruggles, D. Fairchild. The Encyclopaedia of Islam Three (3rd ed.). Brill. p. Garden Form and Variety.

- ^ Lehrman, Jonas Benzion (1980). Earthly Paradise: Garden and Courtyard in Islam. University of California Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-520-04363-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rivers of paradise : water in Islamic art and culture. Blair, Sheila., Bloom, Jonathan (Jonathan M.), Biennial Hamad bin Khalifa Symposium on Islamic Art and Culture (2nd : 2007 : Dawḥah, Qatar). New Haven: Yale University Press. 2009. ISBN 9780300158991. OCLC 317471939.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Graves, Margaret S. (2012). Islamic Art, Architecture and Material Culture : New Perspectives. England: Archaeopress. pp. 93–99. ISBN 978-1407310350. OCLC 818952990.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 210.

- ^ a b Blair, Sheila S. (2009). Rivers of paradise : water in Islamic art and culture. Yale University Press. pp. Chapter 2. ISBN 9780300158991. OCLC 698863162.

- ^ a b c Blair, Sheila. Bloom, Jonathan (Jonathan M.) (2009). Rivers of paradise : water in Islamic art and culture. Yale University Press. pp. Chapter 1. ISBN 9780300158991. OCLC 317471939.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2007). "Gardens". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three (3rd ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-9004161634.

- ^ Husain, Ali Akbar (2012). Scent in the Islamic garden : a study of literary sources in Persian and Urdu (2nd ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780199062782. OCLC 784094302.

- ^ Husain, Ali Akbar. (2012). Scent in the Islamic garden : a study of literary sources in Persian and Urdu (2nd ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780199062782. OCLC 784094302.

- ^ Husain, Ali Akbar. (2012). Scent in the Islamic garden : a study of literary sources in Persian and Urdu (2nd ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780199062782. OCLC 784094302.

- ^ Husain, Ali Akbar. (2012). Scent in the Islamic garden : a study of literary sources in Persian and Urdu (2nd ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780199062782. OCLC 784094302.

- ^ a b Ruggles, Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 17–18, 29.

- ^ Husain, Ali Akbar. (2012). Scent in the Islamic garden : a study of literary sources in Persian and Urdu (2nd ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780199062782. OCLC 784094302.

- ^ a b Ruggles, D. Fairchild. The Encyclopaedia of Islam Three "Gardens" (3rd ed.). Brill. p. Garden Symbolism.

- ^ Mulder, Stephennie (2011). "Reviewed work: Rivers of Paradise: Water in Islamic Art and Culture, Sheila S. Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 131 (4): 646–650. JSTOR 41440522.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 219.

- ^ a b Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 217.

- ^ Ansari, Nazia (2011). "The Islamic Garden" (PDF). p. 27.

- ^ a b Husain, Ali Akbar (2011). "Reading Gardens in Deccani Court Poetry: A Reappraisal of Nusratī's Gulshan-i 'Ishq". In Ali, Daud; Flatt, Emma J. (eds.). Garden and landscape practices in precolonial India : histories from the Deccan. New Delhi. pp. 149–153. ISBN 978-1-003-15787-8. OCLC 1229166032.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-300-21110-8.

- ^ a b Brey, Alexander (March 2018). The Caliph's Prey: Hunting in the Visual Cultures of the Umayyad Empire (PhD). Bryn Mawr College.

- ^ a b Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4025-2.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1976). "Introduction". The Islamic Garden. Washington, D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks. p. 3.

- ^ "The Palaces of the Abbasids at Samarra." In Chase Robinson, ed., A Medieval Islamic City Reconsidered: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Samarra, 29– 67. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ^ a b c d Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0-8122-4025-2.

- ^ a b c d Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–20, 69–70. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ a b Wilbaux, Quentin (2001). La médina de Marrakech: Formation des espaces urbains d'une ancienne capitale du Maroc. Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 69–75. ISBN 2747523888.

- ^ Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P., eds. (2012). "Būstān". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8122-4025-2.

- ^ Navarro, Julio; Garrido, Fidel; Almela, Íñigo (2017). "The Agdal of Marrakesh (Twelfth to Twentieth Centuries): An Agricultural Space for Caliphs and Sultans. Part 1: History". Muqarnas. 34 (1): 23–42. doi:10.1163/22118993_03401P003.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p.155.

- ^ Villiers-Stuart, Constance Mary. Gardens of the Great Mughals. London: A&C Black, 1913, p.162-167.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Nath, Ram. The Immortal Taj, The Evolution of the Tomb in Mughal Architecture. Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala, 1972, p.58-60.

- ^ Koch, Ebba. "The Mughal Waterfront Garden." In Attilio Petruccioli, ed., Gardens in the Time of the Great Muslim Empires. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 172–177. ISBN 978-0-8122-4025-2.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (January 2005). "Robert Elsie, Early Albania. A reader of historical texts 11th–17th centuries". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 97 (2): 575–576. doi:10.1515/byzs.2004.575. ISSN 0007-7704. S2CID 191317575.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Islamic Gardens and Landscapes, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p.189.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Jellicoe, Susan (1976). "A List of Plants". The Islamic Garden. Washington, D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 131–135.

Further reading

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lehrman, Jonas Benzion (1980). Earthly paradise: garden and courtyard in Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 0520043634.

External links

- ICOMOS information on Islamic gardens in Iran

- Archnet.org Islamic architecture community: digital library on agricultural and garden topics

- Islamic arts: Islamic gardens

- Chapter on Mughal Gardens from Dunbarton Oaks

- How to create an Islamic garden of your own Archived 2020-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Petrucciloli, Rethinking the Islamic Garden