History of Eritrea

| History of Eritrea |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Eritrea |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Eritrea is an ancient name, associated in the past with its Greek form Erythraia, Ἐρυθραία, and its derived Latin form Erythræa. This name relates to that of the Red Sea, then called the Erythræan Sea, from the Greek for "red", ἐρυθρός, erythros. But earlier Eritrea was called Mdre Bahri.[1] The Italians created the colony of Eritrea in the 19th century around Asmara and named it with its current name. After World War II, Eritrea annexed to Ethiopia. Following the communist Ethiopian government's defeat in 1991 by the coalition created by armed groups notably the EPLF, Eritrea declared its independence. Eritrea officially celebrated its 1st anniversary of independence on May 24, 1993.

Prehistory

At Buya in Eritrea, one of the oldest hominids representing a possible link between Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens was discovered by Eritrean and Italian scientists. Dated to over 1 million years old, it is the oldest skeletal find of its kind and provides a link between hominids and the earliest anatomically modern humans.[2] It is believed that the section of the Danakil Depression in Eritrea was also a major player in terms of human evolution, and may contain other traces of evolution from Homo erectus hominids to anatomically modern humans.[3]

During the last interglacial period, the Red Sea coast of Eritrea was occupied by early anatomically modern humans.[4] It is believed that the area was on the route out of Africa that some scholars suggest was used by early humans to colonize the rest of the Old World.[5] In 1999, the Eritrean Research Project Team composed of Eritrean, Canadian, American, Dutch and French scientists discovered a Paleolithic site with stone and obsidian tools dated to over 125,000 years old near the Bay of Zula south of Massawa, along the Red Sea littoral. The tools are believed to have been used by early humans to harvest marine resources like clams and oysters.[6]

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic era from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley.[7][8] Other scholars propose that the Afroasiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[9]

Antiquity

Ona culture

Excavations at Sembel found evidence of an ancient pre-Aksumite civilization in greater Asmara. This Ona urban culture is believed to have been among the earliest pastoral and agricultural communities in the Horn region. Artefacts at the site have been dated to between 800 BC and 400 BC, contemporaneous with other pre-Aksumite settlements in the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands during the mid-first millennium BC.[10]

Additionally, the Ona culture may have had connections with the ancient Land of Punt. In a tomb in Thebes dated to the reign of Pharaoh Amenophis II (Amenhotep II), long-necked pots similar to those made by the Ona people are depicted as part of the cargo in a ship from Punt.[11]

Gash Group

Excavations in and near Agordat in central Eritrea yielded the remains of an ancient pre-Aksumite civilization known as the Gash Group.[12] Ceramics were discovered that were related to those of the C-Group (Temehu) pastoral culture, which inhabited the Nile Valley between 2500 and 1500 BC.[13] Sherds akin to those of the Kerma culture, another community that flourished in the Nile Valley around the same period, were also found at other local archaeological sites in the Barka valley belonging to the Gash Group.[12] According to Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst (2000), linguistic evidence indicates that the C-Group and Kerma peoples spoke Afro-Asiatic languages of the Berber and Cushitic branches, respectively.[14][15]

Kingdom of D'mt

D'mt was a kingdom that encompassed most of Eritrea and the northern fringes of Ethiopia, it existed during the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Given the presence of a massive temple complex, its capital was most likely Yeha. Qohaito, often identified as the town Koloe in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,[16] as well as Matara were important ancient D'mt kingdom cities in southern Eritrea. There are many Ancient cities in Eritrea.

The realm developed irrigation schemes, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. After the fall of Dʿmt in the 5th century BC, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms until the rise of one of these polities during the first century, the Kingdom of Aksum, which was able to reunite the area.[17]

Kingdom of Aksum

Debre Sina monastery from the 4th century is the first Christian place of worship recorded in Eritrea. It was the site of the first Holy Communion prepared in the Eritrean Orthodox Church, by the 4th-century bishop Aba Salama. It is one of the oldest monasteries in Africa and the world, as it was probably built in the third century.

Debre Bizen monastery was built during 1350s near the town of Nefasit in Eritrea. The Kingdom of Aksum was a trading empire centered in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia.[18] It existed from approximately 100–940 AD, growing from the proto-Aksumite Iron Age period c. 4th century BC to achieve prominence by the 1st century AD.

The Aksumites established bases on the northern highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau and from there expanded southward. The Persian religious figure Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his time. The origins of the Axumite Kingdom are unclear, although experts have offered their speculations about it. Even whom should be considered the earliest known king is contested: although Carlo Conti Rossini proposed that Zoskales of Axum, mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, should be identified with one Za Haqle mentioned in the Ethiopian King Lists (a view embraced by later historians of Ethiopia such as Yuri M. Kobishchanov[19] and Sergew Hable Sellasie), G.W.B. Huntingford argued that Zoskales was only a sub-king whose authority was limited to Adulis, and that Conti Rossini's identification can not be substantiated.[20]

According to the medieval Liber Axumae (Book of Aksum), Aksum's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[21] Stuart Munro-Hay cites the Muslim historian Abu Ja'far al-Khwarazmi/Kharazmi (who wrote before 833) as stating that the capital of "the kingdom of Habash" was Jarma (hypothetically from Ge'ez girma, "remarkable, revered").[22] The capital was later moved to Aksum in northern Ethiopia. The Kingdom used the name "Axum" as early as the 4th century.[23][24]

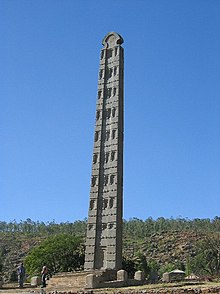

The Aksumites erected a number of large stelae, which served a religious purpose in pre-Christian times. One of these granite columns is the largest such structure in the world, standing at 90 feet.[25] Under Ezana (fl. 320–360), Aksum later adopted Christianity.[26] In 615, during the lifetime of Muhammad, the Aksumite King Sahama provided asylum to early Muslims from Mecca fleeing persecution.[27] This journey is known in Islamic history as the First Hijra. The area is also the alleged resting place of the Ark of the Covenant and the purported home of the Queen of Sheba.[28]

Hawulti (Tigrinya: ሓወልቲ) is a pre-Aksumite obelisk located in Matara, Eritrea. The monument bears the oldest known example of the ancient Ge'ez script.

The kingdom is mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as an important market place for ivory, which was exported throughout the ancient world. Aksum was at the time ruled by Zoskales, who also governed the port of Adulis.[29] The Aksumite rulers facilitated trade by minting their own Aksumite currency.

The state also established its hegemony over the declining Kingdom of Kush and regularly entered the politics of the kingdoms on the Arabian peninsula, eventually extending its rule over the region with the conquest of the Himyarite Kingdom. Inscriptions have been found in Southern Arabia celebrating victories over one GDRT, described as "nagashi of Habashat [i.e. Abyssinia] and of Axum." Other dated inscriptions are used to determine a floruit for GDRT (interpreted as representing a Ge'ez name such as Gadarat, Gedur, or Gedara) around the beginning of the 3rd century. A bronze scepter or wand has been discovered at Atsbi Dera with in inscription mentioning "GDR of Axum". Coins showing the royal portrait began to be minted under King Endubis toward the end of the 3rd century.

Additionally, expeditions by Ezana into the Kingdom of Kush at Meroe in Sudan may have brought about the latter polity's demise, though there is evidence that the kingdom was experiencing a period of decline beforehand. As a result of Ezana's expansions, Aksum bordered the Roman province of Egypt. The degree of Aksum's control over Yemen is uncertain. Though there is little evidence supporting Aksumite control of the region at that time, his title, which includes king of Saba and Salhen, Himyar and Dhu-Raydan (all in modern-day Yemen), along with gold Aksumite coins with the inscriptions, "king of the Habshat" or "Habashite," indicate that Aksum might have retained some legal or actual footing in the area.[30]

Details of the Aksumite Kingdom, never abundant, become even more scarce after this point. The last king known to mint coins is Armah, whose coinage refers to the Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614. Stuart Munro-Hay believes that Axum had been abandoned as the capital by Sahama's reign.[27] However, Kobishchanov suggests that the Axum kingdom retained hegemony over the Arabian ports until at least as late as 702.[31]

Post-classical period

Early developments

From the late first to early second millennium Eritrea witnessed a period of migrations: Since the late 7th century, so with the decline of Aksum, large parts of Eritrea, including the highlands, were overrun by pagan Beja, who supposedly founded several kingdoms on its soil, like Baqlin, Jarin and Qata.[32] The Beja rule declined in the 13th century. Subsequently, the Beja were expelled from the highlands by Abyssinian settlers from the south.[33] Another people, the Bellou, originated from a similar milieu as the Beja. They appeared first in the 12th century, from then on they dominated parts of northwestern Eritrea until the 16th century.[34] After 1270, with the destruction of the Zagwe Kingdom, many Agaw fled to what is now Eritrea. Most were culturally and linguistically assimilated into the local Tigrinya culture, with the notable exception of the Bilen.[35] Yet another people that arrived after the fall of Aksum were the Cushitic-speaking Saho, who had established themselves in the highlands until the 14th century.[36]

Meanwhile, Eritrea witnessed a very slow, but steady conversion to Islam. Muslims had already reached Eritrea in 613/615, during the First Hijra. In 702, Muslim travelers entered the Dahlak islands. In 1060, a Yemeni dynasty fled to Dahlak and proclaimed the Sultanate of Dahlak, which would last for almost 500 years. This sultanate also had sovereignty over the port town of Massawa.[37]

12th century to the Italian arrival

Beginning in the 12th century, however, the Ethiopian Zagwe and Solomonid dynasties held control to a fluctuating extent over the entire plateau and the Red Sea coast of Eritrea.[38][39] Previously, this area has been known as Ma'ikele Bahr ("between the seas/rivers," i.e. the land between the Red Sea and the Mereb river), but during the reign of emperor Zara Yaqob it was rebranded as the domain of the Bahr Negash, the Medri Bahri ("Sea land" in Tigrinya, although it included some areas like Shire on the other side of the Mereb, today in Ethiopia).[40][41] With its capital at Debarwa,[42] the state's main provinces were Hamasien, Serae and Akele Guzai.

The Red Sea coast, having its strategic and commercial importance, was contested by many powers. In the 16th century the Ottomans occupied the Dahlak Archipelago and then Massawa. Also in the 16th century, Eritrea was affected by the invasions of Ahmad Gragn, the Muslim leader of the Sultanate of Adal. After the expulsion of the Adalites, the Ottomans occupied even more of Eritrea's coastal area.[43][44] The Ottoman Empire maintained only tenuous control over much of the territory over the following centuries until 1865, when the Egyptians obtained Massawa from the Ottomans. From there they pushed inland to the plateau, until 1876, when the Egyptians were defeated during the Egyptian-Ethiopian War.[38]

In southern Eritrea, the Aussa Sultanate (Afar Sultanate) succeeded the earlier Imamate of Aussa. The latter polity had come into existence in 1577, when Muhammed Jasa moved his capital from Harar to Aussa (Asaita) with the split of the Adal Sultanate into Aussa and the Sultanate of Harar. At some point after 1672, Aussa declined in conjunction with Imam Umar Din bin Adam's recorded ascension to the throne.[45] In 1734, the Afar leader Kedafu, head of the Mudaito clan, seized power and established the Mudaito dynasty.[46][47] This marked the start of a new and more sophisticated polity that would last into the colonial period.[47]

Italian Eritrea

Establishment

The boundaries of the present-day Eritrea nation state were established during the Scramble for Africa. In 1869[48] or ’70, the then ruling Sultan of Raheita sold lands surrounding the Bay of Assab to the Rubattino Shipping Company.[49] The area served as a coaling station along the shipping lanes introduced by the recently completed Suez Canal. It almost became a part of the Ottoman Habesh Eyalet centered in Egypt, though they withdrew from the place after the resistance of the Eritrean people.[50] The first Italian settlers arrived in 1880.[49]

Later, as the Egyptians retreated out of Sudan during the Mahdist rebellion and failed in their attempts take over the ports and other places on this coast, the British brokered an agreement whereby the Egyptians could retreat through Ethiopia, and in exchange they would allow the Emperor to occupy those lowland districts that he had disputed with the Turks and Egyptians. Emperor Yohannes IV believed this included Massawa, but instead, the port was handed by the British to the Italians, who united it with the already colonised port of Asseb to form a coastal Italian possession. The Italians took advantage of disorder in northern Ethiopia following the death of Emperor Yohannes IV in 1889 to occupy the highlands and established their new colony, henceforth known as Eritrea, and received recognition from Menelik II, Ethiopia's new Emperor.

The Italian possession of maritime areas previously claimed by Abyssinia/Ethiopia was formalized in 1889 with the signing of the Treaty of Wuchale with Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia (r. 1889–1913) after the defeat of Italy by Ethiopia at the battle of Adua where Italy launched an effort to expand its possessions from Eritrea into the more fertile Abyssinian hinterland. Menelik would later renounce the Wuchale Treaty as he had been tricked by the translators to agree to making the whole of Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. However, he was forced by circumstance to live by the tenets of Italian sovereignty over Eritrea.

In the vacuum that followed the 1889 death of Emperor Yohannes IV, Gen. Oreste Baratieri occupied the highlands along the Eritrean coast and Italy proclaimed the establishment of the new colony of Italian Eritrea, a colony of the Kingdom of Italy. In the Treaty of Wuchale (It. Uccialli) signed the same year, King Menelik of Shewa, a southern Ethiopian kingdom, recognized the Italian occupation of his rivals' lands of Bogos, Hamasien, Akkele Guzay, and Serae in exchange for guarantees of financial assistance and continuing access to European arms and ammunition. His subsequent victory over his rival kings and enthronement as Emperor Menelek II (r. 1889–1913) made the treaty formally binding upon the entire territory.[51]

In 1888, the Italian administration launched its first development projects in the new colony. The Eritrean Railway was completed to Saati in 1888,[52] and reached Asmara in the highlands in 1911.[53] The Asmara–Massawa Cableway was the longest of its kind in the world when inaugurated in 1937. It was later dismantled by the British after World War II as war reparations. Besides major infrastructural projects, the colonial authorities invested significantly in the agricultural sector. It also oversaw the provision of urban amenities in Asmara and Massawa, and employed many Eritreans in public service, particularly in the police and public works departments.[54] Thousands of Eritreans were concurrently enlisted in the army, serving during the Italo-Turkish War in Libya as well as the First and second Italo-Abyssinian Wars.

Additionally, the Italian Eritrea administration opened a number of factories, which produced buttons, cooking oil, pasta, construction materials, packing meat, tobacco, hide and other household commodities. In 1939, there were around 2,198 factories and most of the employees were Eritrean citizens. The establishment of industries also made an increase in the number of both Italians and Eritreans residing in the cities. The number of Italians residing in the territory increased from 4,600 to 75,000 in five years; and with the involvement of Eritreans in the industries, trade and fruit plantation was expanded across the nation, while some of the plantations were owned by Eritreans.[55]

In 1922, Benito Mussolini's rise to power in Italy brought profound changes to the colonial government in Italian Eritrea. After il Duce declared the birth of the Italian Empire in May 1936, Italian Eritrea (enlarged with northern Ethiopia's regions) and Italian Somaliland were merged with the just conquered Ethiopia in the new Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana) administrative territory. This Fascist period was characterized by imperial expansion in the name of a "new Roman Empire". Eritrea was chosen by the Italian government to be the industrial center of Italian East Africa. After the revolutional fight by the Eritreans, the Italians left Eritrea.[56]

The Italians brought to Eritrea a huge development of Catholicism. By 1940, nearly one third of the territory's population was Catholic, mainly in Asmara where some churches were built.

Asmara development

Italian Asmara was populated by a large Italian community and the city acquired an Italian architectural look. One of the first building was the Asmara President's Office: this former "Italian government's palace" was built in 1897 by Ferdinando Martini, the first Italian governor of Eritrea. The Italian government wanted to create in Asmara an impressive building, from where the Italian Governors could show the dedication of the Kingdom of Italy to the "colonia primogenita" (first daughter-colony) as was called Eritrea.[57]

Today Asmara is worldwide known for its early twentieth-century Italian buildings, including the Art Deco Cinema Impero, "Cubist" Africa Pension, eclectic Orthodox Cathedral and former Opera House, the futurist Fiat Tagliero Building, the neo-Romanesque Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Asmara, and the neoclassical Governor's Palace. The city is littered with Italian colonial villas and mansions. Most of central Asmara was built between 1935 and 1941, so effectively the Italians managed to build almost an entire city, in just six years.[58]

The city of Italian Asmara had a population of 98,000, of which 53,000 were Italians according to the Italian census of 1939. This fact made Asmara the main "Italian town" of the Italian empire in Africa.In all Eritrea the Italian Eritreans were 75,000 in that year.[59]

Many industrial investments were done by the Italians in the area of Asmara and Massawa, but the beginning of World War II stopped the blossoming industrialization of Eritrea. During the Allied efforts to capture Eritrea from the Italians in spring 1941, most of the infrastructure and the industrial areas were heavily damaged by the fighting.

The following Italian guerrilla war was supported by many Eritrean colonial troops until the Italian armistice in September 1943. Eritrea was placed under British military administration after the Italian surrender in World War II.

The Italian Eritreans strongly rejected the Ethiopian annexation of Eritrea after the war: the Party of Shara Italy of Dr. Vincenzo Di Meglio was established in Asmara in July 1947, and majority of the members were former Italian soldiers and many Eritrean Ascari (the organization was backed up by the government of Italy). This party ruled by Dr. Di Meglio obtained in 1947 the dismissal of a proposal to divide Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia.

The main objective of this italo-Eritrean party was Eritrea freedom, but they had a pre-condition that stated that before independence the country should be governed by Italy for at least 15 years (as with Italian Somalia).

British administration and federalisation

British forces defeated the Italian army in Eritrea in 1941 at the Battle of Keren and placed the colony under British military administration until Allied forces could determine its fate. Several Italian-built infrastructure projects and industries were dismantled and removed to Kenya as war reparations.[60]

In the absence of agreement amongst the Allies concerning the status of Eritrea, the British military administration continued for the remainder of World War II until 1950. During the immediate postwar years, the British proposed that Eritrea be divided along religious lines, with the Muslim population joining Sudan and the Christians Ethiopia. The Soviet Union, anticipating an Italian Communist Party victory in the Italian polls, initially supported returning Eritrea to Italy under trusteeship or as a colony. Soviet diplomats, led by Maxim Litvinov and backed by Ivan Maisky and Vyacheslav Molotov, even attempted to have Eritrea become a trustee of the Soviet Union itself.[61]

Arab states, seeing Eritrea and its large Muslim population as an extension of the Arab world, sought the establishment of an independent state. There are only two main Christian-Muslim conflicts reported in Asmara, Eritrea (the Ethiopians supported by the Unionist Party played a big role in it), one was in 1946 where Sudanese Defence Forces were involved, and the other was in February 1950. This note is about that of 1950.[citation needed]

The UN Commission (UNC) arrived in Eritrea on February 9 and began its months-long inquiry 5 days later. Unionist Shifta activities supported by Ethiopia increased after its arrival, they became daring, better planned, better coordinated and innovative. The main target of the shifta was to disrupt the free movement of the UNC in areas controlled by the independence bloc supporters. The shifta attempted to prevent the rural population that supported independence from having an audience with the UNC. They targeted transportation and communication systems. Telephone lines connecting Asmara with major cities of the predominantly areas pro-independence areas of the western lowlands and Masswa were continuously cut.[citation needed]

An active Muslim League local leader, from Mai Derese, Bashai Nessredin Saeed was killed by the Unionist Shifta while praying, on February 20. According to an account of the incident written by Mufti Sheikh Ibrahim Al Mukhtar, at 07:30 in the evening of a Monday that date 5 shifta came and fired several bullets at him while he was praying. The reason for the killing was that they had asked him to abandon the Muslim League and join the Unionist Party (UP), but he refused. The killing sparked an outrage among Muslims in Asmara. A well organised funeral procession was arranged and attended by youth and Muslim dignitaries. The procession passed through three main streets before they reached the street where the UP Office was located. According to the Mufti, then the UP members started first to throw stones at the procession which was followed by three grenades and then chaos followed. There was open confrontation between both sides and many were killed and injured from both sides. The police intervened by firing live ammunition, but the confrontations continued. Despite all this, the procession continued to the cemetery where the body was buried. The riots then spread to other areas and took a dangerous sectarian form. Many properties were also looted and burned. On Wednesday, the British Military Administration (BMA) declared a curfew, but the riots continued.[citation needed]

On Thursday, the BMA administrator called for a meeting that included the Mufti and Abuna Marcos and asked them to calm the people and ask for reconciliation and both agreed. The wise men from both sides accepted the call, but the looting of properties of Muslim merchants continued for three more days before the riots came to an end.

On Saturday 25 February, the Copts met at the main church and Muslims at the grand mosque and discussed ways to end the violence. Both sides agreed to take an oath to prevent violence against each other. Each side appointed a four-member committee to oversee the agreements. Later 31 members from each side took an oath in front of the eight-member committee. To prevent further violence in other areas, the committee of both sides decided to visit the Muslim and Christian cemeteries and laid flowers on the graveyards of the victims of both sides. More than 62 persons were killed and more than 180 were injured and the damage on the properties was huge. [citation needed] This way the riots, which the Ethiopian Liaison Officer played a big role to ignite, was brought to an end by the wise religious leaders and elders of both sides.

Ethiopian ambition in the Horn was apparent in the expansionist ambition of its monarch when Haile Selassie claimed Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. He made this claim in a letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the Paris Peace Conference and at the First Session of the United Nations.[62] In the United Nations the debate over the fate of the former Italian colonies continued. The British and Americans preferred to cede Eritrea to the Ethiopians if possible as a reward for their support during World War II. "The United States and the United Kingdom have (similarly) agreed to support the cession to Ethiopia of all of Eritrea except the Western province. The United States has given assurances to Ethiopia in this regard."[63] The Independence Bloc of Eritrean parties consistently requested from the UN General Assembly that a referendum be held immediately to settle the Eritrean question of sovereignty.

A United Nations (UN) commission was dispatched to the former colony in February 1950 in the absence of Allied agreement and in the face of Eritrean demands for self-determination. It was also at this juncture that the US Ambassador to the UN, John Foster Dulles, said, "From the point of view of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and the considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country has to be linked with our ally Ethiopia."[64] The Ambassador's word choice, along with the estimation of the British Ambassador in Addis Ababa, makes quite clear the fact that the Eritrean aspiration was for independence.[62]

The commission proposed the establishment of some form of association with Ethiopia, and the UN General Assembly on 2 December 1950 adopted that proposal along with a provision terminating the British military administration of Eritrea no later than 15 September 1952. The British military administration held Legislative Assembly elections on 25 and 26 March 1952, for a representative Assembly of 68 members, evenly divided between Christians and Muslims. This body in turn accepted a draft constitution put forward by the UN commissioner on 10 July. On 11 September 1952, Emperor Haile Selassie ratified the constitution. The Representative Assembly subsequently became the Eritrean Assembly. In 1952 UN General Assembly Resolution 390 to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia went into effect.

The resolution ignored the wishes of Eritreans for independence, but guaranteed the population some democratic rights and a measure of autonomy. Some scholars have contended that the issue was a religious issue, between the Muslim lowland population desiring independence while the highland Christian population sought a union with Ethiopia. Other scholars, including the former Attorney-General of Ethiopia, Bereket Habte Selassie, contend that, "religious tensions here and there...were exploited by the British, [but] most Eritreans (Christians and Moslems) were united in their goal of freedom and independence."[62] Almost immediately after the federation went into effect, however, these rights began to be abridged or violated. Pleas in Eritrea for a referendum for independence were received by the American, British and Ethiopian government, and a confidential American memo estimated around 75% of Eritreans supported the Independence Party.[65]

The details of Eritrea's association with Ethiopia were established by the UN General Assembly Resolution 390A (V) of 2 December 1950. It called for Eritrea and Ethiopia to be linked through a loose federal structure under the sovereignty of the Emperor. Eritrea was to have its own administrative and judicial structure, its own flag, and control over its domestic affairs, including police, local administration, and taxation.[62] The federal government, which for all intents and purposes was the existing imperial government, was to control foreign affairs (including commerce), defense, finance, and transportation. As a result of a long history of a strong landowning peasantry and the virtual absence of serfdom in most parts of Eritrea, the bulk of Eritreans had developed a distinct sense of cultural identity and superiority vis-à-vis Ethiopians. This combined with Eriteans who had a desire for political freedoms alien to Ethiopian political tradition, was the reason why the British administration left the country and the Eritreans finally won that fight. From the start of the federation, however, Haile Selassie attempted to undercut Eritrea's independent status, a policy that alienated many Eritreans. The Emperor pressured Eritrea's elected chief executive to resign, made Amharic the official language in place of Arabic and Tigrinya, terminated the use of the Eritrean flag, imposed censorship, and moved many businesses out of Eritrea. Finally, in 1962 Haile Selassie pressured the Eritrean Assembly to abolish the Federation and join the Imperial Ethiopian fold, much to the dismay of those in Eritrea who favored a more liberal political order.

War for independence

Militant opposition to the incorporation of Eritrea into Ethiopia had begun in 1958 with the founding of the Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM,Arabic: حركات تحرير إريتريا (Movements for liberation of Eritrea), Tigrinya: ማህበር ሸውዓተ Mahber showate (Association of Seven)), an organization made up mainly of students, intellectuals, and urban wage laborers. The ELM, under the leadership of the Eritrean Hamid Idris Awate, engaged in clandestine political activities intended to cultivate resistance to the centralizing policies of the imperial Ethiopian state. By 1962, however, the ELM had been discovered and destroyed by imperial authorities.

Emperor Haile Selassie unilaterally dissolved the Eritrean parliament and illegally annexed the country in 1962. The war continued after Haile Selassie was ousted in a coup in 1974. The Derg, the new Ethiopian government, was a Marxist military junta led by strongman Mengistu Haile Mariam.

In 1960 Eritrean exiles in Cairo founded the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), which led the Eritrean independence struggle during the 1960s. In contrast to the ELM, from the outset the ELF was bent on waging armed struggle on behalf of Eritrean independence. The ELF was composed mainly of Eritrean Muslims from the rural lowlands on the western edge of the territory. In 1961 the ELF's political character was vague, but radical Arab states such as Syria and Iraq saw Eritrea as a predominantly Muslim region struggling to escape Ethiopian oppression and imperial domination. These two countries therefore supplied military and financial assistance to the ELF.

The ELF initiated military operations in 1961 and intensified its activities in response to the dissolution of the federation in 1962. By 1967 the ELF had gained considerable support among peasants, particularly in Eritrea's north and west, and around the port city of Massawa. Haile Selassie attempted to calm the growing unrest by visiting Eritrea and assuring its inhabitants that they would be treated as equals under the new arrangements. Although he doled out offices, money, and titles mainly to Christian highlanders in the hope of co-opting would-be Eritrean opponents in early 1967, the imperial secret police of Ethiopia also set up a wide network of informants in Eritrea and conducted disappearances, intimidations and assassinations among the same populace driving several prominent political figures into exile. Imperial police fired live ammunition killing scores of youngsters during several student demonstrations in Asmara in this time. The imperial army also actively perpetrated massacres until the ousting of the Emperor by the Derg in 1974.

By 1971 ELF activity had become enough of a threat that the emperor had declared martial law in Eritrea. He deployed roughly half of the Ethiopian army to contain the struggle. Internal disputes over strategy and tactics eventually led to the ELF's fragmentation and the founding in 1972 of the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF). The leadership of this multi-ethnic movement came to be dominated by leftist, Christian dissidents who spoke Tigrinya, Eritrea's predominant language. Sporadic armed conflict ensued between the two groups from 1972 to 1974, even as they fought Ethiopian forces. By the late 1970s, the EPLF had become the dominant armed Eritrean group fighting against the Ethiopian Government, and Isaias Afewerki had emerged as its leader. Much of the material used to combat Ethiopia was captured from the army.

By 1977 the EPLF seemed poised to drive the Ethiopians out of Eritrea. However, that same year a massive airlift of Soviet arms to Ethiopia enabled the Ethiopian Army to regain the initiative and forced the EPLF to retreat to the bush. Between 1978 and 1986 the Derg launched eight unsuccessful major offensives against the independence movement. In 1988 the EPLF captured Afabet, headquarters of the Ethiopian Army in northeastern Eritrea, putting approximately a third of the Ethiopian Army out of action and prompting the Ethiopian Army to withdraw from its garrisons in Eritrea's western lowlands. EPLF fighters then moved into position around Keren, Eritrea's second-largest city. Meanwhile, other dissident movements were making headway throughout Ethiopia. At the end of the 1980s the Soviet Union informed Mengistu that it would not renew its defense and cooperation agreement. With the withdrawal of Soviet support and supplies, the Ethiopian Army's morale plummeted, and the EPLF, along with other Ethiopian rebel forces, began to advance on Ethiopian positions. In 1980 the Permanent Peoples' Tribunal determined that the right of the Eritrean people to self-determination does not represent a form of secession.[66]

Provisional Government and People's Front for Democracy and Justice

The United States played a facilitative role in the peace talks in Washington during the months leading up to the May 1991 fall of the Mengistu regime. In mid-May, Mengistu resigned as head of the Ethiopian Government and went into exile in Zimbabwe, leaving a caretaker government in Addis Ababa. Having defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea, EPLF troops took control of their homeland. Later that month, the United States chaired talks in London to formalize the end of the war. These talks were attended by the four major combatant groups, including the EPLF.

Following the collapse of the Mengistu government, Eritrean independence began drawing influential interest and support from the United States. Heritage Foundation Africa expert Michael Johns wrote that "there are some modestly encouraging signs that the front intends to abandon Mengistu's autocratic practices."[67]

A high-level U.S. delegation was also present in Addis Ababa for the July 1–5, 1991 conference that established a transitional government in Ethiopia. The EPLF attended the July conference as an observer and held talks with the new transitional government regarding Eritrea's relationship to Ethiopia. The outcome of those talks was an agreement in which the Ethiopians recognized the right of the Eritreans to hold a referendum on independence.

Although some EPLF cadres at one time espoused a Marxist ideology, Soviet support for Mengistu had cooled their ardor. The fall of communist regimes in the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc convinced them it was a failed system. The EPLF expressed its commitment to establishing a democratic form of government and a free-market economy in Eritrea. The United States agreed to provide assistance to both Ethiopia and Eritrea, conditional on continued progress toward democracy and human rights.

In May 1991 the EPLF established the Provisional Government of Eritrea (PGE) to administer Eritrean affairs until a referendum was held on independence and a permanent government established. EPLF leader Afewerki became the head of the PGE, and the EPLF Central Committee served as its legislative body.

Eritreans voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence between 23 and 25 April 1993 in a UN-monitored referendum. The result of the referendum was 99.83% for Eritrea's independence. The Eritrean authorities declared Eritrea an independent state on 27 April 1993. The government was reorganized and the National Assembly was expanded to include both EPLF and non-EPLF members. The assembly chose Isaias Afewerki as president. The EPLF reorganized itself as a political party, the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ).[68]

After independence

The first President of Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki, has been the President of Eritrea since 1993. People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) is the only legal political party.[69]

On October 25, 1994, the president of Eritrea revoked the citizenship of all of Jehovah's Witnesses born there. While Jehovah's Witnesses are politically neutral, peaceful and obey the laws and pay taxes, they are rounded up and imprisoned simply for their Christian faith.

In July 1996 the Constitution of Eritrea was ratified, but it has yet to be implemented.

In 1998 a border dispute with Ethiopia, over the town of Badme, led to the Eritrean-Ethiopian War in which thousands of soldiers from both countries died. Eritrea suffered from significant economic and social stress, including massive population displacement, reduced economic development, and one of Africa's most severe land mine problems.

The border war ended in 2000 with the signing of the Algiers Agreement. Amongst the terms of the agreement was the establishment of a UN peacekeeping operation, known as the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE); with over 4,000 UN peacekeepers. The UN established a temporary security zone consisting of a 25-kilometre demilitarized buffer zone within Eritrea, running along the length of the disputed border between the two states and patrolled by UN troops. Ethiopia was to withdraw to positions held before the outbreak of hostilities in May 1998. The Algiers agreement called for a final demarcation of the disputed border area between Eritrea and Ethiopia by the assignment of an independent, UN-associated body known as the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), whose task was to clearly identify the border between the two countries and issue a final and binding ruling. The peace agreement would be completed with the implementation of the Border Commission's ruling, which would also end the task of the peacekeeping mission. After extensive study, the Commission issued a final border ruling in April 2002, which awarded some territory to each side, but Badme (the flash point of the conflict) was awarded to Eritrea. The commission's decision was rejected by Ethiopia. The border question remains in dispute, with Ethiopia refusing to withdraw its military from positions in the disputed areas, including Badme, while a "difficult" peace remains in place.

The UNMEE mission was formally abandoned in July 2008, after experiencing serious difficulties in sustaining its troops after fuel stoppages.

Furthermore, Eritrea's diplomatic relations with Djibouti were briefly severed during the border war with Ethiopia in 1998 due to a dispute over Djibouti's intimate relation with Ethiopia during the war but were restored and normalized in 2000. Relations are again tense due to a renewed border dispute. Similarly, Eritrea and Yemen had a border conflict between 1996 and 1998 over the Hanish Islands and the maritime border, which was resolved in 2000 by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

Eritrea has improved health care, and is on track to meet its Millennium Development Goals (MDG) for health, in particular child health.[70] Life expectancy at birth increased from 39.1 years in 1960 to 59.5 years in 2008; maternal and child mortality rates dropped dramatically and the health infrastructure expanded.[70]

Immunisation and child nutrition have been tackled by working closely with schools in a multi-sectoral approach; the number of children vaccinated against measles almost doubled in seven years, from 40.7% to 78.5% and the prevalence of underweight children decreased by 12% from 1995 to 2002 (severe underweight prevalence by 28%).[70] The National Malaria Protection Unit of the Ministry of Health registered reductions in malarial mortality by as much as 85% and in the number of cases by 92% between 1998 and 2006.[70] The Eritrean government has banned female genital mutilation (FGM), saying the practice was painful and put women at risk of life-threatening health problems.[71][70] Malaria and tuberculosis are common.[72] HIV prevalence for ages 15 to 49 years exceeds 2%.[72]

Due to his frustration with the stalemated peace process with Ethiopia, the President of Eritrea Isaias Afewerki wrote a series of Eleven Letters to the UN Security Council and Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Despite the Algiers Agreement, tense relations with Ethiopia have continued and led to regional instability. His government has also been condemned for allegedly arming and financing the insurgency in Somalia; the United States is considering labeling Eritrea a "State Sponsor of Terrorism."[73][74]

In December 2007, an estimated 4000 Eritrean troops remained in the 'demilitarized zone' with a further 120,000 along its side of the border. Ethiopia maintained 100,000 troops along its side.[75]

In September, 2012, the Israeli Haaretz newspaper published an exposé on Eritrea. There are over 40,000 Eritrean refugees in Israel. The NGO Reporters Without Borders has ranked Eritrea in last in freedom of expression since 2007, even lower than North Korea.[76]

The 2013 Eritrean Army mutiny took place on 21 January 2013, when around 100 –200 soldiers of the Eritrean Army in the capital city Asmara briefly seized the headquarters of the state broadcaster, EriTV, and broadcast a message demanding reforms and the release of political prisoners.[77] On 10 February 2013, president Isaias Afwerki commented on the mutiny, describing it as nothing to worry about.[78]

In September 2018, President Isaias Afwerki and Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, signed a historic peace agreement between the two countries.[79]

On 8 July 2017, the entire capital city of Asmara was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with the inscription taking place during the 41st World Heritage Committee Session.[80][81][82][83][84][85]

Relations with neighbours

The BBC published on 19 June 2008 a timeline of Eritrea's conflict with Ethiopia to that date and reported that the "Border dispute rumbles on":[86]

- 2007 September – War could resume between Ethiopia and Eritrea over their border conflict, warns United Nations special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Kjell Magne Bondevik.

- 2007 November – Eritrea accepts border line demarcated by international boundary commission. Ethiopia rejects it.

- 2008 January – UN extends mandate of peacekeepers on Ethiopia-Eritrea border for six months. UN Security Council demands Eritrea lift fuel restrictions imposed on UN peacekeepers at the Eritrea-Ethiopia border area. Eritrea declines, saying troops must leave border.

- 2008 February – UN begins pulling 1,700-strong peacekeeper force out due to lack of fuel supplies following Eritrean government restrictions.

- 2008 April – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon warns of likelihood of new war between Ethiopia and Eritrea if peacekeeping mission withdraws completely. Outlines options for the future of the UN mission in the two countries.

- 2008 May – Eritrea calls on UN to terminate peacekeeping mission.

In relation to the Djiboutian–Eritrean border conflict:

- 2008 April — Djibouti accuses Eritrean troops of digging trenches at disputed Ras Doumeira border area and infiltrating Djiboutian territory.[87] Eritrea denies charge.

- 2008 June – Fighting breaks out between Eritrean and Djiboutian troops.[88]

- 2009, 23 December — the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Eritrea for providing support to armed groups undermining peace and reconciliation in Somalia and because it had not withdrawn its forces following clashes with Djibouti in June 2008. The sanctions consisted of an arms embargo, travel restrictions and a freeze on the assets of its political and military leaders.[89] The sanctions were reinforced on 5 December 2011.[90]

- 2010 June — Djibouti and Eritrea agreed to refer the dispute to Qatar for mediation.[91]

- 2017 June — Following the 2017 Qatar diplomatic crisis, Qatar withdrew its peacekeeping forces from the disputed territory. Shortly after, Djibouti accused Eritrea of reoccupying the mainland hill and Doumeira Island.[92]

In relation to southern Somalia: In December 2009, the United Nations Security Council imposed sanctions on Eritrea, accusing it of arming and providing financial aid to militia groups in southern Somalia's conflict zones.[93] [94] On July 16, 2012, a United Nations Monitoring Group reported that "it had found no evidence of direct Eritrean support for militia groups in the past year."[95]

Since November 2020, Eritrea has been involved in the Tigray War (see Eritrean involvement in the Tigray War).

See also

References

- ^ ἐρυθρός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project. Eritrea was also called Medri Bahri before the arrivalof the Italians.

- ^ McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology (9th ed.). The McGraw Hill Companies Inc. 2002. ISBN 0-07-913665-6.

- ^ "Pleistocene Park". 1999-09-08. Archived from the original on 1999-10-13. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ Walter RC, Buffler RT, Bruggemann JH, et al. (2000). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–9. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. S2CID 4417823.

- ^ Walter, Robert C.; Buffler, RT; Bruggemann, JH; Guillaume, MM; Berhe, SM; Negassi, B; Libsekal, Y; Cheng, H; et al. (2000-05-04). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the lastinterglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–69. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. S2CID 4417823. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "Out of Africa". 1999-09-10. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1990). "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 280 (280): 31–65. doi:10.2307/1357309. JSTOR 1357309. S2CID 163491760.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- ^ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0759104662.

- ^ Schmidt, Peter R. (2002). "The 'Ona' culture of greater Asmara: archaeology's liberation of Eritrea's ancient history from colonial paradigms". Journal of Eritrean Studies. 1 (1): 29–58. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Avanzini, Alessandra (1997). Profumi d'Arabia: atti del convegno. L'ERMA di BRETSCHNEIDER. p. 280. ISBN 8870629759. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ a b Leclant, Jean (1993). Sesto Congresso internazionale di egittologia: atti, Volume 2. International Association of Egyptologists. p. 402. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Cole, Sonia Mary (1964). The Prehistory of East. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 273.

- ^ Marianne Bechaus-Gerst, Roger Blench, Kevin MacDonald (ed.) (2014). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography – "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. p. 453. ISBN 978-1135434168. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Behrens, Peter (1986). Libya Antiqua: Report and Papers of the Symposium Organized by Unesco in Paris, 16 to 18 January 1984 – "Language and migrations of the early Saharan cattle herders: the formation of the Berber branch". Unesco. p. 30. ISBN 9231023764. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, Historical Geography of Ethiopia from the first century AD to 1704 (London: British Academy, 1989), pp. 38f

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard K.P. (17 January 2003)"Let's Look Across the Red Sea I". Archived from the original on 2006-01-09. Retrieved 2013-02-01., Addis Tribune

- ^ David Phillipson: revised by Michael DiBlasi (1 November 2012). Neil Asher Silberman (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780199735785.

- ^ Yuri M. Kobishchanov, Axum, Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator, (University Park, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 1979), pp.54–59.

- ^ Expressed, for example, in his The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: the British Academy, 1989), p.39.

- ^ Africa Geoscience Review, Volume 10. Rock View International. 2003. p. 366. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, pp.95–98.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay (1991). Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (PDF). Edinburgh: University Press. p. 57. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, 2005.

- ^ Brockman, Norbert (2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 30. ISBN 978-1598846546.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 77. ISBN 0748601066. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p.56.

- ^ Raffaele, Paul (December 2007). "Keepers of the Lost Ark?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Periplus of the Erythreaean Sea Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, chs. 4, 5

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 81.

- ^ Kobishchanov, Axum, p.116.

- ^ Dan Connell, Tom Killion (2011): "Historical Dictionary of Eritrea". The Scarecrow. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth. p. 118-119

- ^ Kjetil Tronvoll (1998): "Mai Weini, a Highland Village in Eritrea: A Study of the People". p. 34-35

- ^ Dan Connell, Tom Killion (2011): "Historical Dictionary of Eritrea". The Scarecrow. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth. p. 120-121

- ^ Mussie Tesfagiorgis (2010): "Eritrea". ABC-CLIO. p. 33-34

- ^ Dan Connell, Tom Killion (2011): "Historical Dictionary of Eritrea". The Scarecrow. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth. p. 54

- ^ Dan Connell, Tom Killion (2011): "Historical Dictionary of Eritrea". The Scarecrow. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth. p. 159-160

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia Britannica: History of Eritrea". www.britannica.com.

- ^ Richard Pankhurst (1997): "The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century". Red Sea. Lawrenceville.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p.74.

- ^ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941–2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. United States of America: Signature Book Printing, Inc., 2005, pp.17–8.

- ^ Edward Denison, Guang Yu Ren, Naigzy Gebremedhin Asmara: Africa's secret modernist city, 2003. (page 20)

- ^ Dan Connell, Tom Killion (2011): "Historical Dictionary of Eritrea". The Scarecrow. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth. p. 66-67

- ^ Okbazghi Yohannes (1991). A Pawn in World Politics: Eritrea. University of Florida Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-8130-1044-6. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ Mordechai Abir, The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769–1855 (London: Longmans, 1968), p. 23 n.1.

- ^ Mordechai Abir, The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769–1855 (London: Longmans, 1968), pp. 23–26.

- ^ a b Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea Press. ISBN 0932415199.

- ^ Ullendorff, Edward. The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People 2nd ed., p. 90. Oxford University Press (London), 1965). ISBN 0-19-285061-X.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 747.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 90–119.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Cf. engineer Emilio Olivieri's "La Ferrovia Massaua-Saati". Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-06. report on the construction of the Massawa–Saati Railway] (1888), hosted at Ferrovia Eritrea. (in Italian)

- ^ "Eritrean Railway Archived 2008-02-03 at the Wayback Machine" at Ferrovia Eritrea. (in Italian)

- ^ Eritrea- Contenuti Archived 2008-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Italian administration in Eritrea". Archived from the original on 2015-01-11. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ^ Italian industries in colonial Eritrea Archived April 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ferdinando Martini.RELAZIONE SULLA COLONIA ERITREA – Atti Parlamentari – Legislatura XXI – Seconda Sessione 1902 – Documento N. XVI -Tipografia della Camera dei Deputati. Roma, 1902

- ^ "Reviving Asmara". BBC Radio 3. 2005-06-19. Retrieved 2006-08-30.[dead link]

- ^ http://www.maitacli.it/ [bare URL]

- ^ First reported by Sylvia Pankhurst in her book, Eritrea on the Eve (1947). See Michela Wrong, I didn't do it for you: How the World betrayed a small African nation (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), chapter 6 "The Feminist Fuzzy-wuzzy"

- ^ Vojtech Mastny, The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 23–24; Vladimir O. Pechatnov, "The Big Three After World War II: New Documents on Soviet Thinking about Post-War Relations with the United States and Great Britain Archived 2017-07-06 at the Wayback Machine" (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Cold War International History Project Working Paper 13, May 1995), pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b c d Habte Selassie, Bereket (1989). Eritrea and the United Nations. Red Sea Press. ISBN 0-932415-12-1.

- ^ Top Secret Memorandum of 1949-03-05, written with the UN Third Session in view, from Mr. Rusk to the Secretary of State.

- ^ Heiden, Linda (19 June 1978). "The Eritrean Struggle for Independence". Monthly Review. 30 (2): 15. doi:10.14452/MR-030-02-1978-06_2.

- ^ Department of State, Incoming Telegram, received 1949-08-22, From Addis Ababa, signed MERREL, to Secretary of State, No. 171, 1949-08-19

- ^ "Proceedings of the Permanent Peoples' Tribunal of the International League for the Rights and Liberation of Peoples". Session on Eritrea. Rome, Italy: Research and Information Centre on Eritrea. 1984.

- ^ "Does Democracy Have a Chance?" Archived 2013-08-23 at the Wayback Machine by Michael Johns, The World and I magazine, August 1991 (entered in The Congressional Record, May 6, 1992).

- ^ "A Look Back on Eritrea's Historic 1993 Referendum". 23 April 2018. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Eritrea country profile". BBC News. 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Rodríguez Pose, Romina; Samuels, Fiona (December 2010). "Progress in health in Eritrea: Cost-effective inter-sectoral interventions and a long-term perspective". Overseas Development Institute. London: Overseas Development Institute. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010.

- ^ "IRIN Africa | ERITREA: Government outlaws female genital mutilation | Human Rights". IRIN. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ a b Health profile at Eritrea WHO Country Office Archived 2010-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. afro.who.int

- ^ "US Considers Terror Label for Eritrea". London. Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (2007-09-18). "Eritreans Deny American Accusations of Terrorist Ties". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ "Ethiopia and Eritrea: Bad words over Badme" Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 13 December 2007

- ^ Halper, Yishai (7 September 2012). "'The North Korea of Africa': Where you need a permit to have dinner with friends". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Eritrea mutiny over as government, opposition say 'all calm'". Al-Ahram. AFP. 2013-01-22. Archived from the original on 2021-03-21. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ^ Tekle, Tesfa-Alem (10 February 2013). "Eritrea's president breaks silence over army mutiny incident". Sudan Tribune. Archived from the original on 2013-10-11. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 2019".

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Asmara: A Modernist African City". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Commentary, Tom Gardner (11 July 2017). "Eritrea's picturesque capital is now a World Heritage site and could help bring it in from the cold". Quartz Africa.

- ^ "Eritrea capital, Asmara, makes UNESCO World Heritage list | Africanews". Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Eritrea's capital added to UNESCO World Heritage site list | DW | 08.07.2017". DW.COM.

- ^ "The modernist marvels of Eritrea". Apollo Magazine. 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Exploring Eritrea's UNESCO certified Art-Deco wonderland". The Independent. 9 November 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 2020-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 19 June 2008

- ^ "Djibouti-Eritrea border skirmishes subside as toll hits nine". Agence France-Presse. June 13, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ "US condemns Eritrea 'aggression'". BBC News. June 12, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ "Security Council Imposes Sanctions on Eritrea over Its Role in Somalia, Refusal to Withdraw Troops Following Conflict with Djibouti".

- ^ "Security Council, by Vote of 13 in Favour, Adopts Resolution Reinforcing Sanctions Regime against Eritrea 'Calibrated' to Halt All Activities Destabilizing Region".

- ^ "African Union Praises Eritrea, Djibouti Border Mediation". Voice of America. June 7, 2010. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ "Djibouti, Eritrea in territorial dispute after Qatar peacekeepers leave". Reuters. June 16, 2017.

- ^ "Eritrea rejects U.N. report it backs Somali rebels". Reuters. March 16, 2010. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ "US hits 2 Eritrean army officers with sanctions for supporting radical Somali Islamists". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 2012-07-05. Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "Eritrea reduces support for al Shabaab – U.N. report". Reuters. July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

Further reading

- Peter R. Schmidt, Matthew C. Curtis and Zelalem Teka, The Archaeology of Ancient Eritrea. Asmara: Red Sea Press, 2008. 469 pp. ISBN 1-56902-284-4

- Beretekeab R. (2000); Eritrean making of a Nation 1890–1991, Uppsala University, Uppsala.

- Ghebrehiwot, Petros Kahsai (2006): "A study sample of the Eritrean art and material culture in the collections of the National Museum of Eritrea" Archived 2017-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Mauri, Arnaldo (2004); Eritrea's early stages in monetary and banking development, International Review of Economics, ISSN 1865-1704, Vol. 51, n. 4, pp. 547–569.

- Negash T. (1987); Italian colonisation in Eritrea: policies, praxis and impact, Uppsala University, Uppsala.

- Wrong, Michela. I Didn't Do It For You : How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation. Harper Perennial (2005). ISBN 0-00-715095-4