Banu Ifran

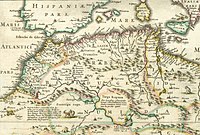

The Banu Ifran (Arabic: بنو يفرن, Banu Yafran) or Ifranids,[1] were a Zenata Berber tribe prominent in the history of pre-Islamic and early Islamic North Africa. In the 8th century, they established a kingdom in the central Maghreb, with Tlemcen as its capital.

Prior to the 8th century, the Banu Ifran resisted or revolted against foreign occupiers—Romans, Vandals, and Byzantines—of their territory in Africa. In the seventh century, they sided with Kahina in her resistance against the Muslim Umayyad invaders. In the eighth century they mobilized around the Sufri dogma, revolting against the Arab Umayyads and Abbasids.

In the 10th century they founded a dynasty opposed to the Fatimids, the Zirids, the Umayyads, the Hammadids and the Maghraoua. The Banu Ifran were defeated by the Almoravids and the invading Arabs (the Banu Hilal and the Banu Sulaym)[2] at the end of the 11th century. The Ifranid dynasty[3] was recognized as the only dynasty that defended the indigenous people of the Maghreb, by the Romans referred to as the Africani.[4] In 11th century Iberia, the Ifranids founded a Taifa of Ronda in 1039[5] at Ronda in Andalusia and governed from Cordoba for several centuries.[6]

Etymology

According to Ibn Khaldun, the Banu Ifran are named after an ancestor, Ifri, whose name in Berber languages meant "cavern".[1]

History

Early history

The oldest mentions concerning the Banu Ifran situate the bulk of their people in the western region of Mauretania Caesariensis.[7] The Banu Ifran were one of the four major tribes of the Zenata or Gaetulia[8] confederation in the Aurès Mountains, and were known as expert cavalrymen. According to Ibn Khaldun, "Ifrinides" or "Ait Ifren" successfully resisted Romans, Vandals and Byzantines who sought to occupy North Africa before the arrival of the Muslim armies. According to Corippus in his Iohannis,[9] during the reign of Justinian I between 547 and 550, the Banu Ifran challenged the Byzantine armies under John Troglita to war.[10][11][12]

At the time of the Arab-Muslim conquests, they were located in the region of Yafran in Tripolitania (present-day Libya). The conquests most likely caused them to move from there to the Aurès region, and an Abbasid invasion of Ifriqiya in 761 likely made them move further into what is now north-western Algeria.[13] Their chief Abu Qurra founded the city of Tlemcen in this region in 765 (over the site of the former Roman city of Pomaria) and established an emirate based here.[1][13]

In the 10th century the Ifranids were enemies with the Fatimid Caliphate, aligning themselves with the Maghrawa tribe and the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, although they themselves became Kharijites. Led by Abu Yazid, they surged east and attacked Kairouan in 945. Another leader, Yala ibn Mohammed captured Oran and constructed a new capital, Ifgan, near Mascara. Under the leadership of their able general Jawhar, who killed Ya'la, in battle in 954,[14] the Fatimids struck back and destroyed Ifgan, and for some time afterward the Banu Ifran reverted to being scattered nomads in perpetual competition with their Sanhaja neighbours. Some settled in regions of Spain, such as Málaga. Others, led by Hammama, managed to gain control of the Moroccan province of Tadla. Later, led by Abu al-Kamāl, they established a new capital at Salé on the Atlantic coast, though this brought them into conflict with the Barghawata tribes on the seaboard.[citation needed] The Banu Ifran had also founded Tadla and Sale where Tamim ibn Ziri built the Great Mosque of Sale.[15][16][17] the Ifrenid emirate fell in 1058, after a Hilalian invasion on western Algeria, in which the Banu Ifren led by Abu Soda collaborated with the Hammadids but were defeated nevertheless, and Abu Soda was killed[18][19] however, their capitultion was not caused by the Arab invasion, as after suffering defeat, Hammadid leader Buluggin ibn Muhammad expediated to Tlemcen in the same year, sacking it and disperising the Banu Ifren into many different tribes[20] it was not until 1066 that the Almoravids led by Ibn Tashfin finished off the tribes by capturing Tlemcen and effectivly ending the Banu Ifren.[21][22]

Banu Ifran in the Maghreb al-Aqsa

During the 11th century, the Banu Ifran contested with the Maghrawa tribe for the control of the Maghreb al-Aqsa (present-day Morocco) after the fall of the Idrisid dynasty. Ya'la's son Yaddū took Fes by surprise in January 993 and held it for some months until the Maghrawa ruler Ziri ibn Atiyya returned from Spain and reconquered the region.

In 1029, the Banu Ifran led by Temim conquered Tamesna from the Barghawata, Temim then expulsed half the population and putting the rest to slavery, he managed to then put his residence there.[23][24]

In May or June 1033, Fes was recaptured by Ya'la's grandson Tamīm. Fanatically devoted to religion, he began a persecution of the Jews,[25] and is said to have killed 6000 of their men while confiscating their wealth and women, but Ibn Khaldun says only persecution without killing.[26] It was described to have been a bloodbath and the women were reduced to slavery while the men were massacred.[27][28] Sometime in the period 1038–1040 the Maghrawa tribe retook Fes, forcing Tamīm to flee to Salé.

Soon after that time, the Almoravids began their rise to power and effectively conquered both the Banu Ifran and their brother-rivals the Maghrawa.

Banu Ifran in Al-Andalus

The Banu Ifran were influential in al-Andalus (present-day Spain) in the 11th century AD: the Ifran house of Corra ruled the Andalusian city of Ronda. Yeddas was the military leader of the Berber troops who were at war against the Christian king and El Mehdi. Abu Nour or Nour of the house of Corra became lord of Ronda and then Seville in Andalusia from 1023 to 1039 and from 1039 to 1054. The son of Nour bin Badis Hallal ruled Ronda from 1054 to 1057, and Abu Nacer from 1057 to 1065.[29][better source needed]

Religion

Before Islam

Among the Ifran, animism was the principal spiritual philosophy. Ifri was also the name of a Berber deity, and their name may have an origin in their beliefs.[30] Ifru rites symbolized in caves were held to gain favor or protection for merchants and traders. The myth of this protection is befittingly depicted on Roman coins.[31][32]

Ifru was regarded as a sun goddess, cave goddess and protector of the home.[33][34] Ifru or Ifran was regarded as a Berber version of Vesta.

Dihya, usually referred to as the Kahina, was the Jarawa Berber queen, prophetess, and leader of the non-Muslim response to the advancing Arab armies. Some historians claim Kahina was Christian,[35] or a follower of the Judaic faith,[25][36][37] though few of the Ifran were Christians, even after more than half a millennium of Christianity among the urban populations and the more sedentary tribes. Ibn Khaldun simply states that the Ifran were Berbers, and says nothing of their religion before the advent of Islam.

During Islam

The Banu Ifran were opposed to the Sunnis of the Arab armies. They eventually converted, but joined the Kharidjite movement within Islam. Ibn Khaldun claimed that the "Zenata people say they are Muslims but they still oppose the Arab army".[38][39] After 711, the Berbers were systematically converted to Islam and many became devout members of the faith.

Notes

- ^ a b c Lewicki, T. (1960–2007). "Banu Ifran". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Histoireg des BerbYres et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique ... – ʻAbd al-Raḥman b. Muḥammad Ibn Khaldчn – Google Livres. 1856. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Histoire politique du Maroc: pouvoir, légitimités, et institutions, ʻAbd al-Laṭīf Aknūsh, Abdelatif Agnouche, p.85, Afrique Orient, 1987 book on line

- ^ Compleḿent de l'Encycloped́ie moderne: dictionnaire abreǵe ́ des sciences, des ... – Noel̈ Desverges, Lжon Renier, Edouard Carteron, Firmin Didot (Firm). – Google Livres. 1857. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Histoire Des Musulmans D'espagne, Reinhart Pieter et Anne Dozy, p.238 Book on line

- ^ Rachel Arié (199O). Études sur la civilisation de l'Espagne musulmane [Studies on the Civilization of Muslim Spain]. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 154. ISBN 90-04-09116-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Agabi, C. "Ifren (Beni)." Encyclopédie berbère 24 (2001): 3657-3659.

- ^ Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société archélologique de la province de Constantine (in French). Alessi et Arnolet. 1874. p. 131.

- ^ Niebuhr, Barthold Georg (1836). Corpus scriptorum historiae byzantinae (in Latin). impensis E. Weberi. p. 90.

- ^ Corripus, la Johannide

- ^ Monographie de l'aurès, Delartigue

- ^ Lipiński, Edward (2004). Itineraria Phoenicia. Peeters Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 978-90-429-1344-8.

- ^ a b Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0521337674.

- ^ So says the Rawd al-Qirtas. But according to Ibn Khaldun, Ya'la died assassinated by a member of the Fatimides in 958.

- ^ ʻAbd al-Laṭīf Aknūsh et Abdelatif Agnouche, Histoire politique du Maroc : pouvoir, légitimités, et institutions, Afrique Orient, 1987

- ^ "وزارة الأوقاف و الشؤون الإسلامية" (in Arabic). Islamic Morocco. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Aḥmad ibn Khālid al-Salāwī, Kitāb el-istiqça li akhbār doual el-Maghrib el-Aqça : Histoire du Maroc, vol. 30–31, Paris, Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1923, p. 156.

- ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1868). Les prolégomènes d'Ibn Khaldoun (in French). Imprimerie impériale.

- ^ Constantine, Société Archéologique de la Province de (1865). Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société Archéologique de la Province de Constantine (in French).

- ^ Lugan, Bernard; Fournel, Bernadette; Fournel, André (2018). Atlas historique de l'Afrique: des origines à nos jours. Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-09644-5.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (7 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-7919-5.

- ^ indigènes, Morocco Direction des affaires (1920). Villes et tribus du Maroc: documents et renseignements (in French). H. Champion.

- ^ Bakrī, Abū ʻUbayd ʻAbd Allāh ibn ʻAbd al-ʻAzīz (1965). كتاب المغرب في ذكر بلاد افريقية والمغرب: وهو جزء من اجزاء الكتاب المعروف بالمسالك والممالك (in French). Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient Adrien-Maisonneuve.

- ^ Journal asiatique (in French). Société asiatique. 1859.

- ^ a b Relations judéo-musulmanes au Marocperceptions et réalités, Michel Abitbol [1]

- ^ Ibn Khaldoun, Histoire des Berbères

- ^ Histoire de l'Afrique septentrionale (Berbérie) depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a la conquête français (1830), Volume 1 Ernest Mercier Ernest Leroux,

- ^ ISRAEL AGAINST ALL ODDS: Anti-Semitism From Its Beginnings to the Holocaust Years Christopher H. K. Persaud Christian Publishing House,

- ^ [2] list of leaders in arabic

- ^ Archives des missions scientifiques et littéraires, France Commission des missions scientifiques et littéraires, France, [3]

- ^ Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société archéologique, historique, du département de Constantine, Arnolet, 1878

- ^ Recueil des notices et mщmoires de la Sociщtщ archщologique, historique, et ... – Google Livres. 1878. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Les cultes païens dans l'Empire romain, Jules Toutain, page 416, p635 and p636

- ^ Toutain, Jules (1920). Les cultes paяens dans l'Empire romain – Jules Toutain – Google Livres. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Moderan, Y. (2005). "Kahena". Encyclopédie Berbère (27): 4102–4111. doi:10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.1306. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ The FalashasA Short History of the Ethiopian Jews, David Kessler

- ^ Ibn Khaldoun, Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale, traduction de William McGuckin de Slane, éd. Paul Geuthner, Paris, 1978, tome 1, pp. 208–209 .

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Histoire des berberes, Traduction Slane, édition Berti

- ^ La Berbérie et L'Islam et la France, Eugène Guernier, party 1, édition de l'union française, 1950

References

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

- Ibn Abi Zar, Rawd al-Qirtas. Annotated Spanish translation: A. Huici Miranda, Rawd el-Qirtas. 2nd edition, Anubar Ediciones, Valencia, 1964. Vol. 1 ISBN 84-7013-007-2.

- C. Agabi (2001), article "Ifren" in Encyclopédie Berbère vol. 24, p. 3657–3659 (Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, ISBN 2-85744-201-7)

- Ibn Khaldun, Kitab el Ibar, French translation (ISBN 2-7053-3638-9)

- Le passé de l'Afrique du Nord. Écrit par E.F. Gautier. Édition Payot, Paris

- KITAB EL-ISTIQÇA. TRADUCTION A. GRAULLE. Auteur AHMED BEN KHALED EN-NACIRI ES-SLAOUI

- Ibn Khaldoun Les prolégomènes El Mokadima

- Gisèle Halimi. Title: La Kahina.