Ian Hacking

Ian Hacking | |

|---|---|

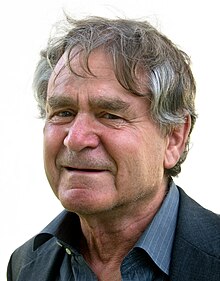

Hacking in 2009 | |

| Born | Ian MacDougall Hacking February 18, 1936 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| Died | May 10, 2023 (aged 87) |

| Alma mater | University of British Columbia Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy |

| Doctoral advisor | Casimir Lewy |

| Doctoral students | David Papineau |

Main interests | Philosophy of science Philosophy of statistics |

Notable ideas | Entity realism Historical ontology (transcendental nominalism) |

Ian MacDougall Hacking CC FRSC FBA (February 18, 1936 – May 10, 2023) was a Canadian philosopher specializing in the philosophy of science. Throughout his career, he won numerous awards, such as the Killam Prize for the Humanities and the Balzan Prize, and was a member of many prestigious groups, including the Order of Canada, the Royal Society of Canada and the British Academy.

Life and career

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, he earned undergraduate degrees from the University of British Columbia (1956) and the University of Cambridge (1958), where he was a student at Trinity College.[2] Hacking also earned his PhD at Cambridge (1962), under the direction of Casimir Lewy, a former student of G. E. Moore.[3]

Hacking started his teaching career as an instructor at Princeton University in 1960 but, after just one year, moved to the University of Virginia as an assistant professor. After working as a research fellow at Peterhouse, Cambridge from 1962 to 1964, he taught at his alma mater, UBC, first as an assistant professor and later as an associate professor from 1964 to 1969. He became a lecturer at Cambridge, again a member of Peterhouse, in 1969 before moving to Stanford University in 1974. After teaching for several years at Stanford, he spent a year at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Bielefeld, Germany, from 1982 to 1983. Hacking was promoted to Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto in 1983 and University Professor, the highest honour the University of Toronto bestows on faculty, in 1991.[3] From 2000 to 2006, he held the Chair of Philosophy and History of Scientific Concepts at the Collège de France. Hacking is the first Anglophone to be elected to a permanent chair in the Collège's history.[4] After retiring from the Collège de France, Hacking was a professor of philosophy at UC Santa Cruz, from 2008 to 2010. He concluded his teaching career in 2011 as a visiting professor at the University of Cape Town.[5]

Hacking was married three times: his first two marriages, to Laura Anne Leach and fellow philosopher Nancy Cartwright, ended in divorce. His third marriage, to Judith Baker, also a philosopher, lasted until her death in 2014. He had two daughters and a son, as well as one stepson.[2]

Hacking died from heart failure at a retirement home in Toronto on May 10, 2023, at the age of 87.[2][6]

Philosophical work

Influenced by debates involving Thomas Kuhn, Imre Lakatos, Paul Feyerabend and others, Hacking is known for bringing a historical approach to the philosophy of science.[7] The fourth edition (2010) of Feyerabend's 1975 book Against Method, and the 50th anniversary edition (2012) of Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions include an Introduction by Hacking. He is sometimes described as a member of the "Stanford School" in philosophy of science, a group that also includes John Dupré, Nancy Cartwright and Peter Galison. Hacking himself identified as a Cambridge analytic philosopher. Hacking was a main proponent of a realism about science called "entity realism."[8] This form of realism encourages a realistic stance towards answers to the scientific unknowns hypothesized by mature sciences (of the future), but skepticism towards current scientific theories. Hacking has also been influential in directing attention to the experimental and even engineering practices of science, and their relative autonomy from theory. Because of this, Hacking moved philosophical thinking a step further than the initial historical, but heavily theory-focused, turn of Kuhn and others.[9]

After 1990, Hacking shifted his focus somewhat from the natural sciences to the human sciences, partly under the influence of the work of Michel Foucault. Foucault was an influence as early as 1975 when Hacking wrote Why Does Language Matter to Philosophy? and The Emergence of Probability. In the latter book, Hacking proposed that the modern schism between subjective or personalistic probability, and the long-run frequency interpretation, emerged in the early modern era as an epistemological "break" involving two incompatible models of uncertainty and chance. As history, the idea of a sharp break has been criticized,[10][11] but competing 'frequentist' and 'subjective' interpretations of probability still remain today. Foucault's approach to knowledge systems and power is also reflected in Hacking's work on the historical mutability of psychiatric disorders and institutional roles for statistical reasoning in the 19th century, his focus in The Taming of Chance (1990) and other writings. He labels his approach to the human sciences transcendental nominalism[12][13] (also dynamic nominalism[14] or dialectical realism),[14] a historicised form of nominalism that traces the mutual interactions over time between the phenomena of the human world and our conceptions and classifications of them.[15]

In Mad Travelers (1998) Hacking provided a historical account of the effects of a medical condition known as fugue in the late 1890s. Fugue, also known as "mad travel," is a diagnosable type of insanity in which European men would walk in a trance for hundreds of miles without knowledge of their identities.[16]

Awards and lectures

In 2002, Hacking was awarded the first Killam Prize for the Humanities, Canada's most distinguished award for outstanding career achievements. He was made a Companion of the Order of Canada (CC) in 2004.[17] Hacking was appointed visiting professor at University of California, Santa Cruz for the Winters of 2008 and 2009. On August 25, 2009, Hacking was named winner of the Holberg International Memorial Prize, a Norwegian award for scholarly work in the arts and humanities, social sciences, law and theology.[18]

In 2003, he gave the Sigmund H. Danziger Jr. Memorial Lecture in the Humanities, and in 2010 he gave the René Descartes Lectures at the Tilburg Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science (TiLPS). Hacking also gave the Howison lectures at the University of California, Berkeley, on the topic of mathematics and its sources in human behavior ('Proof, Truth, Hands and Mind') in 2010. In 2012, Hacking was awarded the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art, and in 2014 he was awarded the Balzan Prize.[19]

Selected works

Books

Hacking's works have been translated into several languages. His works include:

- Logic of Statistical Inference (1965)[20]

- A Concise Introduction to Logic (1972) ISBN 039431008X

- The Emergence of Probability (1975)[21]

- Why Does Language Matter to Philosophy? (1975)[22]

- Scientific Revolutions (1981) ISBN 019875051X

- Representing and Intervening, Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1983.[23][24]

- The Taming of Chance (1990)[25]

- Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory (1995)[26][27]

- Mad Travelers: Reflections on the Reality of Transient Mental Illnesses (1998)[28]

- The Social Construction of What? (1999)[29]

- An Introduction to Probability and Inductive Logic (2001)[30]

- Historical Ontology (2002) ISBN 9780674016071[31]

- Why Is There Philosophy of Mathematics at All? (2014) ISBN 9781107050174

Chapters in books

- Hacking, Ian (1992), "The self-vindication of the laboratory sciences", in Pickering, Andrew (ed.), Science as practice and culture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 29–64, ISBN 978-0-226-66801-7.

- Hacking, Ian (1996), "The Looping Effects of Human Kinds", in Sperber, Dan; Premack, David; Premack, Ann James (eds.), Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Debate, Oxford University Press, pp. 351–394, ISBN 9780191689093

Articles

- Hacking, Ian (1967). "Slightly More Realistic Personal Probability". Philosophy of Science. 34 (4): 311–325. doi:10.1086/288169. S2CID 14344339.

- 1979: "What is Logic?", Journal of Philosophy 76(6), reprinted in A Philosophical Companion to First Order Logic (1993), edited by R.I.G. Hughes

- Hacking, Ian (1988). "Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design". Isis. 79 (3): 427–451. doi:10.1086/354775. S2CID 52201011.

- Hacking, I. (2005). "Truthfulness". Common Knowledge. 11: 160–172. doi:10.1215/0961754X-11-1-160. S2CID 258005264.

- Hacking, Ian (2006). "Genetics, biosocial groups & the future of identity". Daedalus. 135 (4): 81–95. doi:10.1162/daed.2006.135.4.81. S2CID 57563796.

- 2007: "Root and Branch: A Canadian philosopher surveys some of the livelier flashpoints in America's battle over evolution". Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Nation

- Hacking, Ian (January 1, 2007). "Putnam's Theory of Natural Kinds and Their Names is Not the Same as Kripke's". Principia: An International Journal of Epistemology (in Portuguese). 11 (1): 1–24. ISSN 1808-1711.

References

- ^ Storm, Jason Josephson (2021). Metamodernism: The Future of Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-226-78665-0.

- ^ a b c Williams, Alex (May 28, 2023). "Ian Hacking, Eminent Philosopher of Science and Much Else, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Ian Hacking, Philosopher". www.ianhacking.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ Jon Miller, "Review of Ian Hacking, Historical Ontology", Theoria 72(2) (2006), p. 148. doi:10.1111/j.1755-2567.2006.tb00951.x

- ^ "Ian Hacking fonds - Discover Archives". discoverarchives.library.utoronto.ca. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "In memoriam: Ian Hacking (1936-2023)". Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (2002). Historical Ontology. Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1n3x198. ISBN 978-0-674-00616-4. JSTOR j.ctv1n3x198.

- ^ Boaz Miller. "What is Hacking's Argument for Entity Realism?". philarchive.org. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Grandy, Karen. "Ian Hacking". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ Garber, Daniel; Zabell, Sandy (1979). "On the emergence of probability". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 12 (1): 33–53. doi:10.1007/BF00327872. JSTOR 41133550. S2CID 121660640. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Franklin, James (2001). The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 373. ISBN 0-8018-6569-7.

- ^ See Transcendence (philosophy) and Nominalism.

- ^ A view that Hacking also ascribes to Thomas Kuhn (see D. Ginev, Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Issues and Images in the Philosophy of Science: Scientific and Philosophical Essays in Honour of Azarya Polikarov, Springer, 2012, pp. 313–315).

- ^ a b Ş. Tekin (2014), "The Missing Self in Hacking's Looping Effects".

- ^ "Root and Branch". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "Dissociative Amnesia, DSM-IV Codes 300.12 ( Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition )". Psychiatryonline.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Mr. Ian Hacking". Governor General of Canada. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Michael Valpy (August 26, 2009). "From autism to determinism, science to the soul". The Globe and Mail. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ "Ian Hacking – Balzan Prize Epistemology/Philosophy of Mind". www.balzan.org. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ Hacking, Ian; Romeijn, Jan-Willem (2016). Logic of Statistical Inference – Ian Hacking. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316534960. ISBN 9781107144958.

- ^ Barnouw, Jeffrey (1979). "Review of The Emergence of Probability: A Philosophical Study of Early Ideas About Probability, Induction and Statistical Inference". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 12 (3): 438–443. doi:10.2307/2738528. ISSN 0013-2586. JSTOR 2738528.

- ^ Loeb, Louis E. (1977). "Review of Why does Language Matter to Philosophy?". The Philosophical Review. 86 (3): 437–440. doi:10.2307/2183805. ISSN 0031-8108. JSTOR 2183805.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (October 20, 1983). Representing and Intervening: Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28246-8.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (1983). Representing and Intervening: Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28246-8.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (1990). The Taming of Chance. Ideas in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38014-0.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (1995). Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05908-2. JSTOR j.ctt7rr17.

- ^ "Rewriting the soul: Multiple personality and the sciences of memory". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (1998). Mad travelers: reflections on the reality of transient mental illnesses. Page-Barbour lectures for (1. publ ed.). Charlottesville, Va.: Univ. Press of Virginia. ISBN 978-0-8139-1823-5.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (November 15, 2000). The Social Construction of What?. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00412-2.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (July 2, 2001). An Introduction to Probability and Inductive Logic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77501-4.

- ^ Hyder, David (June 1, 2003). "Review of Historical Ontology". Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. ISSN 1538-1617.

Further reading

- Ruphy, Stéphanie (2011). "From Hacking's Plurality of Styles of Scientific Reasoning to "Foliated" Pluralism: A Philosophically Robust Form of Ontologico-Methodological Pluralism". Philosophy of Science. 78 (5). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1212–1222. Bibcode:2010SHPSA..41..158K. doi:10.1086/664571. S2CID 144717363.

- Kusch, Martin (2010). "Hacking's historical epistemology: a critique of styles of reasoning". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 41 (2). Elsevier BV: 158–173. Bibcode:2010SHPSA..41..158K. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2010.03.007. ISSN 0039-3681.

- Resnik, David B. (1994). "Hacking's Experimental Realism". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 24 (3). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 395–411. doi:10.1080/00455091.1994.10717376. ISSN 0045-5091. S2CID 142532335.

- Sciortino, Luca (2017). "On Ian Hacking's Notion of Style of Reasoning". Erkenntnis. 82 (2). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 243–264. doi:10.1007/s10670-016-9815-9. ISSN 0165-0106. S2CID 148130603.

- Sciortino, Luca (2016). "Styles of Reasoning, Human Forms of Life, and Relativism". International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 30 (2). Informa UK Limited: 165–184. doi:10.1080/02698595.2016.1265868. ISSN 0269-8595. S2CID 151642764.

- Tsou, Jonathan Y. (2007). "Hacking on the Looping Effects of Psychiatric Classifications: What Is an Interactive and Indifferent Kind?". International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 21 (3). Informa UK Limited: 329–344. doi:10.1080/02698590701589601. ISSN 0269-8595. S2CID 121742010.

- Vesterinen, Tuomas (2020). "Identifying the Explanatory Domain of the Looping Effect: Congruent and Incongruent Feedback Mechanisms of Interactive Kinds: Winner of the 2020 Essay Competition of the International Social Ontology Society". Journal of Social Ontology. 6 (2). De Gruyter: 159–185. doi:10.1515/jso-2020-0015. ISSN 2196-9663. S2CID 232106024.

- Sciortino, Luca (2023), History of Rationalities: Ways of Thinking from Vico to Hacking and Beyond, New York: Springer- Palgrave McMillan, pp. 1–351, ISBN 978-3-031-24003-4.

- Martínez Rodríguez, María Laura (2021) Texture in the Work of Ian Hacking. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-64785-8

External links

| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- Official website

- Ian Hacking archival papers held at the University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services

- Hacking, Ian (1936–), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy