Hurdy-gurdy

| |

| Other names | Wheel fiddle, wheel vielle, vielle à roue, zanfona, draailier, ghironda |

|---|---|

| Classification | String instrument (bowed) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-72 (Composite chordophone sounded by rosined wheel) |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by a hand-crank-turned, rosined wheel rubbing against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin (or nyckelharpa) bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar to those of a violin. Melodies are played on a keyboard that presses tangents—small wedges, typically made of wood or metal—against one or more of the strings to change their pitch. Like most other acoustic stringed instruments, it has a sound board and hollow cavity to make the vibration of the strings audible.

Most hurdy-gurdies have multiple drone strings, which give a constant pitch accompaniment to the melody, resulting in a sound similar to that of bagpipes. For this reason, the hurdy-gurdy is often used interchangeably or along with bagpipes. It is mostly used in Occitan, Aragonese, Cajun French, Asturian, Cantabrian, Galician, Hungarian, and Slavic folk music. It can also be seen in early music settings such as medieval, renaissance or baroque music.[1] One or more of the gut strings called 'trompette' usually passes over a buzzing bridge called the 'chien' that can be made to produce a distinctive percussive buzzing sound as the player turns the wheel.

History

The hurdy-gurdy is generally thought to have originated from fiddles in either Europe or the Middle East (e.g., the rebab instrument) before the eleventh century A.D.[2] The first recorded reference to fiddles in Europe was in the 9th century by the Persian geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih (d. 911) describing the lira (lūrā) as a typical instrument within the Byzantine Empire.[3] One of the earliest forms of the hurdy-gurdy was the organistrum, a large instrument with a guitar-shaped body and a long neck in which the keys were set (covering one diatonic octave). The organistrum had a single melody string and two drone strings, which ran over a common bridge, and a relatively small wheel. Due to its size, the organistrum was played by two people, one of whom turned the crank while the other pulled the keys upward. Pulling keys upward is cumbersome, so only slow tunes could be played on the organistrum.[4]

The pitches on the organistrum were set according to Pythagorean temperament and the instrument was primarily used in monastic and church settings to accompany choral music. Abbot Odo of Cluny (died 942) is supposed to have written a short description of the construction of the organistrum entitled Quomodo organistrum construatur (How the Organistrum Is Made),[5][6] known through a much later copy, but its authenticity is very doubtful. Another 10th-century treatise thought to have mentioned an instrument like a hurdy-gurdy is an Arabic musical compendium written by Al Zirikli.[2] One of the earliest visual depictions of the organistrum is from the twelfth-century Pórtico da Gloria (Portal of Glory) on the cathedral at Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain: it has a carving of two musicians playing an organistrum.[7]: 47 [8]: 3

Later, the organistrum was made smaller to let a single player both turn the crank and work the keys. The solo organistrum was known from Spain and France, but was largely replaced by an improved variant, known as a symphonia, in the 13th century, a small box-shaped version of the hurdy-gurdy with three strings and a diatonic keyboard. At about the same time, a new form of key pressed from beneath was developed. These keys were much more practical for faster music and easier to handle; eventually they completely replaced keys pulled up from above. Medieval depictions of the symphonia show both types of keys.

During the Renaissance, the hurdy-gurdy was a very popular instrument (along with the bagpipe) and the characteristic form had a short neck and a boxy body with a curved tail end. It was around this time that buzzing bridges first appeared in illustrations. The buzzing bridge (commonly called the dog) is an asymmetrical bridge that rests under a drone string on the sound board. When the wheel is accelerated, one foot of the bridge lifts from the soundboard and vibrates, creating a buzzing sound. The buzzing bridge is thought to have been borrowed from the tromba marina (monochord), a bowed string instrument.

During the late Renaissance, two characteristic shapes of hurdy-gurdies developed. The first was guitar-shaped and the second had a rounded lute-type body made of staves. The lute-like body is especially characteristic of French instruments.

By the end of the 17th century changing musical tastes demanded greater polyphonic capabilities than the hurdy-gurdy could offer and pushed the instrument to the lowest social classes; as a result it acquired names like the German Bauernleier 'peasant's lyre' and Bettlerleier 'beggar's lyre'. During the 18th century, however, French Rococo tastes for rustic diversions brought the hurdy-gurdy back to the attention of the upper classes, where it acquired tremendous popularity among the nobility, with famous composers writing works for the hurdy-gurdy. The most famous of these is Nicolas Chédeville's Il pastor Fido, published under the name Antonio Vivaldi. At this time the most common style of hurdy-gurdy developed, the six-string vielle à roue. This instrument has two melody strings and four drones. The drone strings are tuned so that by turning them on or off, the instrument can be played in multiple keys (e.g., C and G, or G and D).

During this time the hurdy-gurdy also spread further to Central Europe, where further variations developed in western Slavic countries, German-speaking areas and Hungary (see the list of types below for more information on them). Most types of hurdy-gurdy were essentially extinct by the early twentieth century, but a few have survived. The best-known are the French vielle à roue, the Hungarian tekerőlant, and the Spanish zanfoña. In Ukraine, a variety called the lira was widely used by blind street musicians, most of whom were purged by Stalin in the 1930s (see Persecuted bandurists).[unreliable source?]

The hurdy-gurdy tradition is well-developed particularly in Hungary, Poland, Belarus, Southeastern France and Ukraine. In Ukraine, it is known as the lira or relia. It was and still is played by professional, often blind, itinerant musicians known as lirnyky. Their repertoire has mostly para-religious themes. Most of it originated in the Baroque period. In Eastern Ukraine, the repertoire includes unique historic epics known as dumy and folk dances.

Lirnyky were categorised as beggars by the Russian authorities and fell under harsh repressive measures if they were caught performing in the streets of major cities until 1902, when the authorities were asked by ethnographers attending the 12th All-Russian Archaeological conference to stop persecuting them.

The hurdy-gurdy is the instrument played by Der Leiermann, the street musician portrayed in the last, melancholy song of Schubert's Winterreise. It is also featured and played prominently in the film Captains Courageous (1937) as the instrument of the character Manuel, played by Spencer Tracy.

The instrument came into a new public consciousness when Donovan released his hit pop song "Hurdy Gurdy Man" in 1968. Although the song does not use a hurdy-gurdy, the repeated reference to the instrument in the song's lyrics sparked curiosity and interest among young people, eventually resulting in an annual hurdy-gurdy music festival in the Olympic Peninsula area of the state of Washington each September.[9]

Today, the tradition has resurfaced. Revivals have been underway for many years as well in Austria, Belarus, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands,[10]: 85–116 Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and Ukraine. As the instrument has been revived, musicians have used it in a variety of styles of music (see the list of recordings that use hurdy-gurdy), including contemporary forms not typically associated with it.

Terminology

A person who plays the hurdy-gurdy is called a hurdy-gurdist, or (particularly for players of French instruments) viellist.

In France, a player is called un sonneur de vielle (literally "a sounder of vielle"), un vielleux or un vielleur.

Because of the prominence of the French tradition, many instrument and performance terms used in English are commonly taken from the French, and players generally need to know these terms to read relevant literature. Such common terms include:

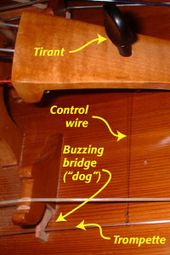

- Trompette: the highest-pitched drone string that features the buzzing bridge

- Mouche: the drone string pitched a fourth or fifth below the trompette

- Petit bourdon: the drone string pitched an octave below the trompette

- Gros bourdon: the drone string pitched an octave below the mouche

- Chanterelle(s): melody string(s), also called chanters or chanter strings in English

- Chien: (literally "dog"), the buzzing bridge

- Tirant: a small peg set in the instrument's tailpiece that is used to control the sensitivity of the buzzing bridge

Nomenclature

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the mid 18th century origin of the term hurdy-gurdy is onomatopoeic in origin, after the repetitive warble in pitch that characterizes instruments with solid wooden wheels that have warped due to changes in humidity or after the sound of the buzzing-bridge.[11] Alternately, the term is thought to come from the Scottish and northern English term for uproar or disorder, hirdy-girdy[7]: 41 or from hurly-burly,[7]: 40 an old English term for noise or commotion. The instrument is sometimes more descriptively called a wheel fiddle in English, but this term is rarely used among players of the instrument. Another possible derivation is from the Hungarian hegedűs (Slovenian variant hrgadus) meaning a fiddle.[12]

In France, the instrument is known as vielle à roue (wheel fiddle) or simply vielle (even though there is another instrument with this name), while in the French-speaking regions of Belgium it is also known in local dialects as vièrlerète/vièrlète or tiesse di dj'va ('horse's head').[7]: 38 The Flemings and the Dutch call it a draailier, which is similar to its German name, Drehleier. An alternate German name, Bauernleier, means "peasant's lyre". In Italy, it is called the ghironda or lira tedesca while in Spain, it is a zanfona in Galicia, zanfoña in Zamora, rabil in Asturias and viola de roda in Catalonia. In the Basque language, it is known as a zarrabete. In Portugal, it is called sanfona.[13]: 211–221

The Hungarian name tekerőlant and the alternative forgólant both mean "turning lute". Another Hungarian name for the instrument is nyenyere, which is thought to be an onomatopoeic reference to the repetitive warble produced by a wheel that is not even. This term was considered derogatory in the Hungarian lowlands, but was the normal term for the instrument on Csepel island directly south of Budapest.[citation needed] The equivalent names ninera and niněra are used in Slovakia and the Czech Republic respectively. In Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian the instrument is called "wheel lyre" (колёсная лира, колісна ліра, колавая ліра). In Poland it is called "cranked lyre" (lira korbowa).

Leier, lant, and related terms today are generally used to refer to members of the lute or lyre family, but historically had a broader range of meaning and were used for many types of stringed instruments.

In the eighteenth century, the term hurdy-gurdy was also applied to a small, portable barrel organ or street organ (a cranked box instrument with a number of organ pipes, a bellows and a barrel with pins that rotated and programmed the tunes) that was frequently played by poor buskers, street musicians specifically called organ grinders. Such organs require only the turning of the crank to play; the music is coded by pinned barrels, perforated paper rolls, and, more recently, by electronic modules.[14] The French call these organs Orgue de Barbarie ("Barbary organ"), while the Germans and Dutch say Drehorgel and draaiorgel ("turned organ"), instead of Drehleier ("turning lyre"). In Czech, the organ is called flašinet.

Design

Shape

In her overview of the instrument's history, Palmer recorded twenty-three different forms,[7]: 23–34 and there is still no standardized design today.

The six-stringed French vielle à roue is the best-known and most common sort. A number of regional forms developed, but outside France the instrument was considered a folk instrument and there were no schools of construction that could have determined a standard form.

There are two primary body styles for contemporary instruments: guitar-bodied and lute-backed. Both forms are found in French-speaking areas, while guitar-bodied instruments are the general form elsewhere. The box form symphonia is also commonly found among players of early music and historical re-enactors.

Strings

Historically, strings were made of gut, which is still a preferred material today and modern instruments are mounted with violin (D or A) and cello (A, G, C) strings.[8]: 10–12 However, metal-wound strings have become common in the twentieth century, especially for the heavier drone strings or for lower melody strings if octave tuning is used. Nylon is also sometimes used, but is disliked by many players. Some instruments also have optional sympathetic strings, generally guitar or banjo B strings.[8]: 10–12

The drone strings produce steady sounds at fixed pitches. The melody string(s) (French chanterelle(s), Hungarian dallamhúr(ok)) are stopped with tangents attached to keys that change the vibration length of the string, much as a guitarist uses his or her fingers on the fretboard of a guitar. In the earliest hurdy-gurdies these keys were arranged to provide a Pythagorean temperament, but in later instruments the tunings have varied widely, with equal temperament most common because it allows easier blending with other instruments. However, because the tangents can be adjusted to tune individual notes, it is possible to tune hurdy-gurdies to almost any temperament as needed. Most contemporary hurdy-gurdies have 24 keys that cover a range of two chromatic octaves.

To achieve proper intonation and sound quality, each string of a hurdy-gurdy must be wrapped with cotton or similar fibers. The cotton on melody strings tends to be quite light, while drone strings have heavier cotton. Improper cottoning results in a raspy tone, especially at higher pitches. In addition, individual strings (in particular the melody strings) often have to have their height above the wheel surface adjusted by having small pieces of paper placed between the strings and the bridge, a process called shimming. Shimming and cottoning are connected processes since either one can affect the geometry of the instrument's strings.

Buzzing bridge

In some types of hurdy-gurdy, notably the French vielle à roue ('fiddle with a wheel') and the Hungarian tekerőlant (tekerő for short), makers have added a buzzing bridge—called a chien (French for dog) or recsegő (Hungarian for "buzzer")—on one drone string. Modern makers have increased the number of buzzing bridges on French-style instruments to as many as four. This mechanism consists of a loose bridge under a drone string. The tail of the buzzing bridge is inserted into a narrow vertical slot (or held by a peg in Hungarian instruments) that holds the buzzing bridge in place (and also serves as a bridge for additional drone strings on some instruments).

The free end of the dog (called the hammer) rests on the soundboard of the hurdy-gurdy and is more or less free to vibrate. When the wheel is turned regularly and not too fast the pressure on the string (called the trompette on French instruments) holds the bridge in place, sounding a drone. When the crank is struck, the hammer lifts up suddenly and vibrates against the soundboard, producing a characteristic rhythmic buzz that is used as an articulation or to provide percussive effect, especially in dance pieces.

On French-style instruments, the sensitivity of the buzzing bridge can be altered by turning a peg called a tirant in the tailpiece of the instrument that is connected by a wire or thread to the trompette. The tirant adjusts the lateral pressure on the trompette and thereby sets the sensitivity of the buzzing bridge to changes in wheel velocity. When hard to trigger, the strike or the bridge is said "sec" (dry), "chien sec", or "coup sec". When easy to trigger, the strike or the bridge is said "gras" (fat), "chien gras", or "coup gras".

There are various stylistic techniques that are used as the player turns the crank, striking the wheel at various points in its revolution. This technique is often known by its French term, the coup-de-poignet (or, more simply, the shortened coup). The percussion is transmitted to the wheel by striking the handle with the thumb, fingers or base of the thumb at one or more of four points in the revolution of the wheel (often described in terms of the clock face, 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock) to achieve the desired rhythm. A long buzz can also be achieved by accelerating the wheel with the handle. It is called either "un glissé" (a slide) or "une trainée" (a streak). More accomplished players are able to achieve six, eight, or even twelve buzzes within one turn of the wheel.

On the Hungarian tekerő the same control is achieved by using a wedge called the recsegőék (control wedge, or literally "buzzer wedge") that pushes the drone string downward. In traditional tekerő playing, the buzzing bridge is controlled entirely by the wrist of the player and has a very different sound and rhythmic possibilities from those available on French instruments.

Regional types

Regional types of hurdy-gurdies since the Renaissance can also be classified based on wheel size and the presence or absence (and type) of a buzzing bridge. The following description of various types uses this framework:[15][16]: 23–40

Small wheel

Small-wheeled (wheel diameter less than 14 cm, or about 5.5 inches) instruments are traditionally found in Central and Eastern Europe. They feature a broad keybox and the drone strings run within the keybox. Because of the small size of the wheel these instruments most commonly have three strings: one melody string, one tenor drone, and one bass drone. They sometimes have up to five strings.

- String-adjusted buzzing bridge

- German pear-shaped Drehleier. Two to three drone strings and one or two chromatic melody strings. Characteristic V-shaped pegbox. Often extensively decorated. The type of buzzing bridge found on this instrument usually has the adjustment peg set in a block next to the string, rather than in the tailpiece (as is typical of French instruments).

- lira/vevlira (Sweden). Revived in the twentieth century based on historical examples. Two body forms: an elongated boxy shape and a long pear shape. Usually diatonic, but has been extended with a chromatic range with the additional keys placed below the normal diatonic range (the opposite of most chromatic hurdy-gurdy keyboards).

- Wedge-adjusted buzzing bridge

- tekerőlant (Hungarian). Usually two drones (sometimes three) + one or two chromatic melody strings. The broad keybox is often carved or decorated extensively.

- Tyrolian Drehleier (Austria). Very similar to the tekerőlant, but usually has a diatonic keyboard. May be the historical source for the tekerő.[15]

- No buzzing bridge

Slovak-style hurdy-gurdy (ninera) made and played by Tibor Koblicek - lira korbowa (Poland). Guitar-shaped. Two drones + one diatonic melody string.

- lira/лира (Russia). Guitar-shaped. Two drones + one diatonic melody string. Evenly spaced keyboard.

- lira/ліра or relia/реля (Ukraine). Guitar-shaped. Two drones + one diatonic melody string. Two body types: carved from a single piece of wood and guitar-shaped with transverse pegs and mult-piece construction with vertical pegs. Evenly spaced keyboard.

- ninera/kolovratec (Slovakia). Guitar-shaped. Two drones + one diatonic melody string. Broad keybox. Superficially similar to the tekerő, but lacks the buzzing bridge.

- German tulip-shaped Drehleier. Three drones + one diatonic melody string.

Large wheel

Large-wheeled instruments (wheel diameters between 14 and 17 cm, or about 5.5 – 6.6 inches) are traditionally found in Western Europe. These instruments generally have a narrow keybox with drone strings that run outside the keybox. They also generally have more strings, and doubling or tripling of the melody string is common. Some modern instruments have as many as fifteen strings played by the wheel, although the most common number is six.

- String-adjusted buzzing bridge

- vielle à roue (French). Usually four drones + two melody strings, but often extended to have more strings. Two body forms: guitar-bodied and lute-backed (vielle en luth). French instruments generally have a narrow key box with drone strings that run on the outside of the key box. Traditional French instruments have two melody strings and four drone strings with one buzzing bridge. Contemporary instruments often have more: the instrument of well-known player Gilles Chabenat has four melody strings fixed to a viola tailpiece, and four drone strings on a cello tailpiece. This instrument also has three trompette strings.

- Niněra (Czech). Guitar-shaped. Two forms: one has a standard drone-melody arrangement, while the other runs the drone strings between the melody strings in the keybox. Both diatonic and chromatic forms are found. Other mechanisms for adjusting the amount of "buzz" on the trompette string.

- No buzzing bridge

- Zanfona (Spain). Typically guitar-shaped body, with three melody strings, and two drone strings. Some older examples had a diatonic keyboard, and most modern models have a chromatic keyboard. Zanfonas are usually tuned to the key of C major, with the melody strings tuned in unison to G above the middle C on the piano. The drones are: the bordonciño in G (one octave below the melody strings) and the bordón in C (two octaves below middle C). Sometimes, two of the melody strings are in unison, and the remaining string is tuned an octave lower, in unison with the bordonciño (this string was sometimes known as the human voice, because it sounds as if someone is humming the melody an octave lower).

- niněra (Czech). Guitar-shaped. Two forms: one has a standard drone-melody arrangement, while the other runs the drone strings between the melody strings in the keybox. Both diatonic and chromatic forms are found.

Electric and electronic versions

In pop music, especially in the popular neo-medieval music, electric hurdy-gurdies are used, wherein electro magnetic pickups convert the vibration of its strings into electrical signals. Similar to electric guitars, the signals are transmitted to an instrument amplifier or reproduced by synthesizer in a modified form.[17]

Electronic hurdy-gurdies, on the other hand, have no strings. The signals for the melody strings are generated electronically by the keys and also in combination with the rotation of the wheel. The signals for drone strings and the snares are generated by the crank movements of the wheel. Depending on the technical equipment of the instrument, the digital audio signal can be output directly via an integrated processor and sound card. The data exchange of the musical information between the hurdy-gurdy and connected computers, samplers or synthesizers are managed via MIDI interface.[18]

Musicians

See also

- Bowed clavier

- Donskoy ryley

- Dulcigurdy

- Kaisatsuko

- Nyckelharpa

- Recordings featuring the hurdy-gurdy

- Viola organista

- The Gizmo

References

- ^ "Hurdy-Gurdy (Baroque) – Early Music Instrument Database".

- ^ a b Baines, Anthony (May 1976). "Reviewed work(s): Die Drehleier, ihr Bau und ihre Geschichte by Marianne Bröcker". The Galpin Society Journal. 29: 140–141 [140]. doi:10.2307/841885. JSTOR 841885.

- ^ Margaret J. Kartomi: On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology, University of Chicago Press, 1990

- ^ Christopher Page, "The Medieval Organistrum and Symphonia. 1: A Legacy From the East?," The Galpin Society Journal 35:37–44, and "The Medieval Organistrum and Symphonia. 2: Terminology," The Galpin Society Journal 36:71–87

- ^ Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra potissimum, 3 vols., ed. Martin Gerbert (St. Blaise: Typis San-Blasianis, 1784; reprint ed., Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), 1:303. Available online at http://www.chmtl.indiana.edu/tml/9th-11th/ODOORG_TEXT.html

- ^ Franz Montgomery, "The Etymology of the Phrase by Rote." Modern Language Notes 46/1 (Jan. 1931), 19–21.

- ^ a b c d e Palmer, Susann (1980). The Hurdy-Gurdy. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7888-0.

- ^ a b c Muskett, Doreen (1998). Hurdy-Gurdy Method. England: Muskett Music. ISBN 0-946993-07-6.

- ^ About the Over The Water Hurdy-Gurdy Association. From the 'Over The Water' website. Retrieved on January 9, 2014

- ^ Anthoons, Jan; Dewit, Herman, eds. (1983). Volksmuziekatelier — Jaarboek 1. Lennik, Belgium: Jan Verhoeven.

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionaries online entry for hurdy-gurdy". oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Slovene Folklore, Author(s): F. S. Copeland, Source: Folklore, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Dec. 31, 1931)

- ^ Veiga de Oliveira, Ernesto (2000) [1964]. Instrumentos Musicais Populares Portugueses. Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. ISBN 972-666-075-0.

- ^ Azumi, Eric (27 April 2017). "Hurdy Gurdy History: History Of The Hurdy Gurdy". Lark in the Morning. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ a b Lommel, Arle; Nagy, Balázs (April 2007). "The Form, History and Classification of the Tekerőlant (Hungarian Hurdy-Gurdy)". The Galpin Society Journal. 60. London and New York: The Galpin Society: 181–190. JSTOR i25163886.

- ^ Description of types based on Nagy, Balázs (2006). Tekerőlantosok könyve: Hasznós kézikönyv tekerőlant-játékosok és érdeklődők számára / The Hurdy-Gurdy Handbook: A Practical Handbook for Players and Aficionados of the Tekerő (Hungarian Hurdy-Gurdy). Budapest: Hagyományok Háza / Hungarian Heritage House. ISBN 963-7363-10-6. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ Izci, Aylin (2017-06-23). "Alles andere als altmodisch: die elektrische Drehleier" [All-other than old-fashioned: the electric hurdy-gurdy]. enemy.at (in German). Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Banshee in Avalon (2014-11-27). "A Hurdy Gurdy and MIDI controller". audiofanzine. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

Further reading

- "Hurdy-gurdy: contemporary destinations" (2012), dissertation by Piotr Nowotnik

- "Hurdy-gurdy: new articulations" (2016), dissertation by Piotr Nowotnik

External links

- Hurdy-gurdy for beginners Archived 2014-02-18 at the Wayback Machine (video), a TED talk by Caroline Phillips with Mixel Ducau

- A demonstration of hurdy-gurdies from Poland from the Polish National Institute of Music and Dance