Terminology of homosexuality

Terms used to describe homosexuality have gone through many changes since the emergence of the first terms in the mid-19th century. In English, some terms in widespread use have been sodomite, Achillean, Sapphic, Uranian, homophile, lesbian, gay, effeminate, queer, homoaffective, and same-gender attracted. Some of these words are specific to women, some to men, and some can be used of either. Gay people may also be identified under the umbrella term LGBT.

Homosexual was coined in German in 1868.[1] Academia continues to coin related terms, including androphilia and gynephilia which designate only the object of attraction, thus divorcing the terms from sexual orientation entirely.

Numerous slang terms exist for homosexuals or homosexuality. Some communities have cants, a rich jargon used among a subgroup almost like a secret language, such as Polari in the UK, and others.

Prescribed usage

The term homosexual can be used as an adjective to describe the sexual attractions and behaviors of people attracted to the same sex. Author and gay pioneer Quentin Crisp said that the term should be "homosexualist", adding that no one says "I am a sexual."[2] Some gay people argue that the use of homosexual as a noun is offensive, arguing that they are people first and their homosexuality being merely an attribute of their humanity. Even if they do not consider the term offensive, some people in same-gender relationships may object to being described as homosexual because they identify as bisexual+, or another orientation.[3]

Some style guides recommend that the terms homosexual and homosexuality be avoided altogether, lest their use cause confusion or arouse controversy. In particular, the description of individuals as homosexual may be offensive, partially because of the negative clinical association of the word stemming from its use in describing same-gender attraction as a pathological state before homosexuality was removed from the American Psychiatric Association's list of mental disorders in 1973.[4] The Associated Press and New York Times style guides restrict usage of the terms.[5]

Same-gender oriented people seldom apply such terms to themselves, and public officials and agencies often avoid them. For instance, the Safe Schools Coalition of Washington's Glossary for School Employees advises that gay is the "preferred synonym for homosexual",[6] and goes on to suggest avoiding the term homosexual as it is "clinical, distancing, and archaic".

However, the terms homosexual and homosexuality are sometimes deemed appropriate in referring to behavior (although same-gender is the preferred adjective). Using homosexuality or homosexual to refer to behavior may be inaccurate but does not carry the same potentially offensive connotations that using homosexual to describe a person does. When referring to people, homosexual might be considered derogatory and the terms gay and lesbian are preferred. Some have argued that homosexual places emphasis on sexuality over humanity, and is to be avoided when describing a person. Gay man or lesbian are the preferred nouns for referring to people, which stress cultural and social matters over sex.[6]

The New Oxford American Dictionary[7] says that gay is the preferred term.

People with a same-gender sexual orientation generally prefer the terms gay, lesbian, or bisexual. The most common terms are gay (both men and women) and lesbian (women only). Other terms include same gender loving and same-sex-oriented.[4]

Among some sectors of gay sub-culture, same-gender sexual behavior is sometimes viewed as solely for physical pleasure instead of romantic. Men on the down-low (or DL) may engage in covert sexual activity with other men while pursuing sexual and romantic relationships with women.

History

The choice of terms regarding sexual orientation may imply a certain political outlook, and different terms have been preferred at different times and in different places.

Early history

Historian and philosopher Michel Foucault argued that homosexual and heterosexual identities did not emerge until the 19th century. Prior to that time, he said, the terms described practices and not identity. Foucault cited Karl Westphal's famous 1870 article Contrary Sexual Feeling as the "date of birth" of the categorization of sexual orientation.[8] Some scholars, however, have argued that there are significant continuities between past and present conceptualizations of sexuality, with various terms having been used for homosexuality.[9][10]

In his Symposium, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato described (through the character of the profane comedian Aristophanes) three sexual orientations – heterosexuality, male homosexuality, and female homosexuality – and provided explanations for their existence using an invented creation myth.[11]

Tribadism

Although this term refers to a specific sex act between women today, in the past it was commonly used to describe female-female sexual love in general, and women who had sex with women were called Tribads or Tribades. As author Rictor Norton explains:

The tribas, lesbian, from Greek tribein, to rub (i.e. rubbing the pudenda together, or clitoris upon pubic bone, etc.), appears in Greek and Latin satires from the late first century. The tribade was the most common (vulgar) lesbian in European texts for many centuries. 'Tribade' occurs in English texts from at least as early as 1601 to at least as late as the mid-nineteenth century before it became self-consciously old-fashioned—it was in current use for nearly three centuries.[12]

Fricatrice, a synonym for tribade that also refers to rubbing but has a Latin rather than a Greek root, appeared in English as early as 1605 (in Ben Jonson's Volpone). Its usage suggests that it was more colloquial and more pejorative than tribade. Variants include the Latinized confricatrice and English rubster.[13]

Sodomy

Though sodomy has been used to refer to a range of homosexual and heterosexual "unnatural acts", the term sodomite usually refers to a homosexual male even though the real meaning is of unreproductive sex.[14][15] The term is derived from the Biblical tale of Sodom and Gomorrah, and Christian churches have referred to the crimen sodomitae (crime of the Sodomites) for centuries. The modern association with homosexuality can be found as early as AD 96 in the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus. In the early 5th century, Jerome, a priest, historian, and theologian used the forms Sodoman, in Sodomis, Sodomorum, Sodomæ, Sodomitæ.[16] The modern German word Sodomie and the Norwegian sodomi also refer to bestiality.[17][18] Sodomy in historical biblical reference may not pertain to the acts of homosexuality, but the acts of bestiality and female and male castration for the purpose of sexual slavery.[citation needed]

Lesbianism

Lesbian writer Emma Donoghue found that the term lesbian (with its modern meaning) has been in use in the English language from at least the 18th century. The 1732 epic poem by William King, The Toast, uses "lesbian loves" and "tribadism" interchangeably: "she loved Women in the same Manner as Men love them; she was a Tribad".[19]

Sapphism

Named after the female Greek poet Sappho who lived on Lesbos Island and wrote love poems to women, this term has been in use since at least the 18th century, with the connotation of lesbian. In 1773, a London magazine described sex between women as "Sapphic passion".[20] The adjective form Sapphic is sometimes used nowadays as an inclusive umbrella term that expresses the sexuality and romantic attraction of queer women, including bisexuals, nonbinary, and trans people[21][22][23][24] However, this is not accepted by all women who identify as lesbian.[citation needed]

Pederasty

Today, pederasty refers to male attraction towards adolescent boys,[25] or the cultural institutions that support such relations, as in ancient Greece.[26] However, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the word usually referred to male homosexuality in general.[citation needed] A pederast was also the active partner in anal sex, whether with a male or a female partner.[citation needed] This relationship is socially frowned upon in modern cultures while legally defined by the age of consent.

Homosexual

The word homosexual translates literally as "of the same sex", being a hybrid of the Greek prefix homo- meaning 'same' (as distinguished from the Latin root homo meaning 'human') and the Latin root sex meaning 'sex'.

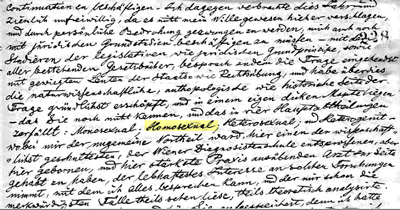

The first known public appearance of the term homosexual in print is found in an 1869 German pamphlet 143 des Preussischen Strafgesetzbuchs und seine Aufrechterhaltung als 152 des Entwurfs eines Strafgesetzbuchs für den Norddeutschen Bund ("Paragraph 143 of the Prussian Penal Code and Its Maintenance as Paragraph 152 of the Draft of a Penal Code for the North German Confederation"). The pamphlet was written by Karl-Maria Kertbeny, but published anonymously. It advocated the repeal of Prussia's sodomy laws.[27] Kertbeny had previously used the word in a private letter written in 1868 to Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. Kertbeny used Homosexualität (in English, 'homosexuality') in place of Ulrichs' Urningtum; Homosexualisten ('male homosexualists') instead of Urninge, and Homosexualistinnen ('female homosexualists') instead of Urninden.

The term was coined and originally used primarily by German psychiatrists and psychologists. Havelock Ellis in his 1901 Studies in the Psychology of Sex wrote about the evolving terminology in the area, which ended up settling on homosexuality. In the preface to the first edition (1900), Ellis calls it sexual inversion, and volume 2 of the book is titled "Sexual Inversion". In the preface to the third edition (1927) Ellis referred to it as "the study of homosexuality". On the first page of chapter 1, he discusses the terminology, naming Ulrichs' use of Uranian (German: Uranier) from 1862, which later morphed into Urning, and using Urningtum as the name of the condition. Ellis reported that the first accepted scientific term was contrary sexual feeling (Konträre Sexualempfindung), coined by Westphal in 1869, and used by Krafft-Ebing and others. This term was never used outside Germany, and soon went out of favor even there. The term homosexuality was invented by Kertbeny in the same year (1869) but attracted no attention for some time, later achieving prominence, and was easily translatable into many languages, including by Hirschfeld in his 1914 book Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes, one of the top authorities in the field. Ellis continued to use both the terms sexual inversion and homosexuality in the 3rd edition, with slightly different meanings.[28]

The first known use of homosexual in English is in Charles Gilbert Chaddock's 1892 translation of Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis, a study on sexual practices.[29] The term was popularized by the 1906 Harden–Eulenburg Affair.

The word homosexual itself had different connotations 100 years ago than today. Although some early writers used the adjective homosexual to refer to any single-gender context (such as an all-girls school),[citation needed] today the term implies a sexual aspect. The term homosocial is now used to describe single-sex contexts that are not of a romantic or sexual nature.[30]

The colloquial abbreviation homo for homosexual is a coinage of the interbellum period, first recorded as a noun in 1929, and as an adjective in 1933.[31] Today, it is often considered a derogatory epithet.[32][5]

Other late 19th and early 20th century sexological terms

- Antipathic sexual instinct: deviant sexual behavior outlined in Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Pychopathia Sexualis[33]

- Sexual inversion[34]

- Psychosexual hermaphroditism: bisexuality. It was believed gay men desired a female body and lesbians desired a male body. Bisexuals desired to become intersex.[35]

- The intermediate sex: similar to sexual inversion, Edward Carpenter believed gay men possessed a male body and a female temperament and vice versa for lesbians[36]

- Similisexualism, simulsexuality[37] or similsexualism: homosexuality[38]

- Intersexuality[39][citation needed]

- Catamite[40]

- Invert[40]

- Third sex[40]

Homophile

Coined by the German astrologist, author and psychoanalyst Karl-Günther Heimsoth in his 1924 doctoral dissertation Hetero- und Homophilie, the term was in common use in the 1950s and 1960s by homosexual organizations and publications; the groups of this period are now known collectively as the homophile movement.[41] Popular in the 1950s and 1960s (and still in occasional use in the 1990s, particularly in writing by Anglican clergy),[42] the term homophile was an attempt to avoid the clinical implications of sexual pathology found with the word homosexual, emphasizing love (-phile) instead.[43] The first element of the word, the Greek root homo-, means 'same'; it is unrelated to Latin homo, 'person'. In almost all languages where the words homophile and homosexual were both in use (i.e., their cognate equivalents: German Homophil and Homosexuell, Italian omofilo and omosessuale, etc.), homosexual won out as the modern conventional neutral term. However, in Norway, the Netherlands and the Flemish/Dutch part of Belgium, the term is still widely used.[44]

Recent academic terms

Not all terms have been used to describe same-gender sexuality are synonyms for the modern term homosexuality. Anna Rüling,[45] one of the first women to publicly defend gay rights, considered gay people a third gender, different from both men and women. Terms such as gynephilia and androphilia have tried to simplify the language of sexual orientation by making no claim about the individual's own gender identity. However, they are not commonly used.

Side

Side[46] describes someone who does not practice anal sex and therefore does not define himself as top, bottom or versatile.

This term is sometimes used in American literature[47] to present an alternative to the binary classification which notes the preferred sexual position, such as top or bottom; the term side indicates one's affinity for neither of this binary classification.[48]

Jargon and slang

Cants

There are established languages of slang (sometimes known as cants) such as Polari in Britain, Swardspeak in the Philippines, Bahasa Binan in Indonesia, Lubunca in Turkey, and Kaliardá (Καλιαρντά) in Greece.[citation needed]

Slang

A variety of LGBT slang terms have been used historically and contemporarily within the LGBT community.

In addition to the stigma surrounding homosexuality, terms have been influenced by taboos around sex in general, producing a number of euphemisms. A gay person may be described as "that way", "a bit funny", "light in his loafers", "on the bus", "batting for the other team", "a friend of Dorothy", "women who wear comfortable shoes" (lesbians), although such euphemisms are becoming less common as homosexuality becomes more visible.[citation needed]

Harry Hay frequently stated that, in the 1930s–1940s, gay people referred to themselves as temperamental.[49]

Gay

Although the word was originally synonymous with happy or cheerful, in the 20th century it gradually came to designate someone who is romantically or sexually attracted to someone of the same gender or sex.[50]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Feray, Jean-Claude, and Manfred Herzer. 1990. « Homosexual Studies and Politics in the 19th Century »: Journal of Homosexuality 19 (1): 23‑48. p.29.

- ^ Quentin Crisp on the gay liberation movement, 1977: CBC Archives. CBC. June 28, 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Savin-Williams, Ritch C. (July 14, 2016). "Bisexual, Not Bisexual". Psychology Today.

- ^ a b GLAAD GLAAD Media Reference Guide - Terms To Avoid Archived 2012-04-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b GLAAD GLAAD Media Reference Guide - AP & New York Times Style Archived 2014-11-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Glossary" (PDF). Safe Schools Coalition. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ^ "NOAD". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ Foucault, 1976

- ^ Norton, Rictor (2016). Myth of the Modern Homosexual. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781474286923. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-06-01. The author has made adapted and expanded portions of this book available online as A Critique of Social Constructionism and Postmodern Queer Theory Archived 2019-03-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Boswell, John (1989). "Revolutions, Universals, and Sexual Categories" (PDF). In Duberman, Martin Bauml; Vicinus, Martha; Chauncey, George Jr. (eds.). Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Penguin Books. pp. 17–36. S2CID 34904667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-04.

- ^ Classical Myth Archived 2005-04-05 at the Wayback Machine on glbtq.com

- ^ Rictor Norton (July 12, 2002). "A Critique of Social Constructionism and Postmodern Queer Theory, "The 'Sodomite' and the 'Lesbian'". infopt.demon.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ Andreadis, Harriette (2001). Sappho in Early Modern England: Female Same-Sex Literary Erotics, 1550–1714. University of Chicago Press. pp. 41, 49–51. ISBN 0-226-02009-6.

- ^ Albert Barnes' Notes on the Bible

- ^ Vincent's Word Studies

- ^ Hallam 1993

- ^ "Duden | Sodomie | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition, Herkunft". www.duden.de (in German). Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ "Ordbøkene.no - Bokmålsordboka og Nynorskordboka". ordbokene.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ Trumbach, Randolph (1994). De Jean, Joan; Dekker, Rudolf M.; van de Pol, Lotte C.; Dugaw, Dianne; Faderman, Lillian; Kennedy, Elizabeth Lapovsky; Davis, Madeline D.; Lewin, Ellen; Newton, Esther (eds.). "The Origin and Development of the Modern Lesbian Role in the Western Gender System: Northwestern Europe and the United States, 1750-1990". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 20 (2): 287–320. ISSN 0315-7997. JSTOR 41298998.

- ^ "Anonymous (1773),The Covent Garden Magazine Or the Amorous Repository, Vol.2, London, p.226". 1773. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "What Does It Mean to Be Sapphic?". them. 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Sapphic - What is it? What does it mean?". Taimi. 3 December 2021. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Identidade sáfica: como uma poeta nascida há 2 mil anos virou referência nos estudos de gênero". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2021-06-26. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Sapphic - What Does Sapphic Mean?". Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ Based on the OED definition: "A man who has or desires sexual relations with a boy."

- ^ "Ancient Greek Pederasty: Education or Exploitation?". StMU Research Scholars. December 3, 2017.

- ^ Bullough et al. ed. (1996)

- ^ Ellis, Havelock (1927) [1900]. "Chapter I.—Introduction". Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Vol. II Sexual Inversion (3rd, revised and enlarged ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. pp. 1–4. OCLC 786194611. Archived from the original on 2019-12-06.

- ^ David Halperin, One Hundred Years of Homosexuality, Routledge, 1990, page 15

- ^ Merl Storr, Latex and Lingerie (2003) pp. 39–40

- ^ OED, "homo, n.2 and a."

- ^ Wolinsky and Sherrill (eds.), Gays and the military: Joseph Steffan versus the United States, Princeton University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-691-01944-4, pp. 49–55.

- ^ Used by Richard von Krafft-Ebing in "Psychopathia Sexualis, with Special Reference to the Antipathic Sexual Instinct: A Medico-Forensic Study", 1886.

- ^ Used by Krafft-Ebing and also Havelock Ellis and John Addington Symonds in "Sexual Inversion", 1897. Popularised by Radclyffe Hall's use of it in her novel The Well of Loneliness.

- ^ Used by Krafft-Ebing and later Ellis to mean bisexuality, as opposed to complete inversion (exclusive homosexuality). Freud uses the term in "Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality" (1905) to refer to male homosexuality.

- ^ Used by Edward Carpenter in "The Intermediate Sex", 1908

- ^ "simulsexual - Dictionary of sexual terms". www.sex-lexis.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-08. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ^ Used by Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson [writing as Xavier Mayne] in "The Intersexes: A History of Similisexualism as a Problem in Social Life", 1908.

- ^ Used around 1900 as a synonym for "inversion"; the term now has a different meaning—see intersexuality.

- ^ a b c Gifford (1995). Dayneford's Library American Homosexual Writing, 1900-1913. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-87023-993-7.

- ^ Clayton Whisnant (2012). Male Homosexuality in West Germany — Between Persecution and Freedom, 1945–69. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137028341. ISBN 978-1-349-34681-3. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- ^ Issues in Human Sexuality: A Statement by the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England, December 1991 (London: Church House Publishing, 1991). "Annotated Notes on Issues in Human Sexuality". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ MD, Reidar Kjær (2003-02-25). "Look to Norway? Gay Issues and Mental Health Across the Atlantic Ocean". Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy. 7 (1–2): 55–73. doi:10.1300/J236v07n01_05. ISSN 0891-7140. S2CID 142840589.

- ^ "Homofili", from Norsk (nynorsk) Wikipedia Archived 2008-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, entry retrieved 2012-06-19. Original text: "I den grad «homophile» hadde fått noko gjennomslag i engelsk og amerikansk, overtok «homosexual», «gay» og «lesbian» denne plassen frå slutten av 1960-talet. «Homofili» blei første gong nytta på norsk i ein brosjyre av den norske avdelinga av det danske «Forbundet af 1948» i 1951. Noreg er eit av dei få (det einaste?) landet der dette omgrepet framleis har stor utbreiing."

- ^ Rowold, Katharina (1865–1914). The Educated Woman: Minds, Bodies, and Women's Higher Education in Britain. Germany and Spain: Routledge. ISBN 1-134-62584-7.

- ^ "Side Guys: Thinking Beyond Gay Male "Tops" and "Bottoms" | Psychology Today". www.psychologytoday.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ "Meet The 'Sides,' Gay Men Who Don't Like Anal Sex". MEL Magazine. 2019-05-09. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ Kort, Joe (2013-04-16). "Guys On The 'Side': Looking Beyond Gay Tops And Bottoms". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ "Harry Hay Interview - The Progressive". progressive.org. 2016-08-09. Archived from the original on 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- ^ "gay". Online Etymology Dictionary.

References

- Dalzell, Tom; Victor, Terry (2007). The concise new Partridge dictionary of slang and unconventional English. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21259-5.

- Dalzell, Tom (2008). The Routledge dictionary of modern American slang and unconventional English. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-37182-7.

- Dynes, Wayne R.; Johansson, Warren; Percy, William A.; Donaldson, Stephen (1990). Encyclopedia of homosexuality, Volume 1. Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-6544-7.

- Green, Jonathon (2005). Cassell's dictionary of slang (2 ed.). Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-304-36636-1.

- Marks, Georgette A.; Johnson, Charles Benjamin; Pratt, Jane (1984). Harrap's Slang dictionary: English-French/French-English. Harrap. ISBN 978-0-245-54047-9.

- Partridge, Eric; Dalzell, Tom; Victor, Terry (2006). The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: J-Z (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-25938-5.

- Schemann, Hans; Knight, Paul (1995). German-English dictionary of idioms. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14199-4.

External links

- "Gay Language Guide" – gay slang in various languages: French, German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, Japanese, Hungarian, Russian, Thai

- "The Homophobic Alphabet Euphemism Collection" Archived 2010-01-31 at the Wayback Machine: an ongoing collection of euphemisms for gay men and lesbians.

- Homosexual Terms in 18th-century Dictionaries – catamite, madge, indorser, windward passage, and more