Holdingham

| Holdingham | |

|---|---|

Cottages in the hamlet | |

Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Civil parish | |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

Holdingham is a hamlet in the civil parish and built-up area of Sleaford, in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It is bisected by Lincoln Road (B1518) which joins the A17 and A15 roads immediately north of the settlement; those roads connect it to Lincoln, Newark, Peterborough and King's Lynn. Sleaford railway station is on the Nottingham to Skegness (via Grantham) and Peterborough to Lincoln Lines.

Prehistoric and Romano-British artefacts have been uncovered around Holdingham. There was an early and middle Saxon settlement, which appears to have disappeared in the 9th century. The current settlement's Old English name suggests a pre-conquest origin, though it was not mentioned in the Domesday Book and appears to have formed part of the Bishop of Lincoln's manor of New Sleaford. Holdingham probably functioned as the agricultural focus of the manor, while New Sleaford (0.9 miles or 1.5 km south) was encouraged to expand as a commercial centre. The land was ceded to the Crown in 1540 and was acquired by Robert Carre in 1559; it passed through his family and then, through marriage, to the Earls (later Marquesses) of Bristol, who owned almost all of the land. Enclosed in 1794, it remained a small, primarily agricultural settlement well into the 20th century.

The late 20th century brought substantial change. Holdingham Roundabout was built immediately north of the hamlet in 1975 as part of the A17 bypass around Sleaford; the roundabout also accommodated the A15 bypass which opened in 1993. After Lord Bristol sold the agricultural land around the hamlet, major residential development began; private suburban housing estates were completed either side of Lincoln Road between Sleaford and Holdingham in the 1990s and early 2000s. The hamlet thereby merged into Sleaford's urban area. Further developments took place in the 2010s and more housing has been approved for building in the 2020s on land between Holdingham and The Drove to the south-west.

Holdingham had its own chapel in the Middle Ages, but this was abandoned c. 1550; its site has not been identified securely. It has had a public house since at least the early 19th century, serving drovers bringing their cattle from Scotland to London. The hamlet now has petrol filling stations on the roundabout and Lincoln Road, as well as fast food restaurants, a hotel, a café and a nursing home – all opened since the middle of the 20th century. The nearest schools and other public services are in Sleaford. The hamlet was anciently part of the parish of New Sleaford; in 1866, the civil parish of Holdingham was established but in 1974 was merged into Sleaford civil parish. The hamlet now lends its name to a ward in North Kesteven, although the boundaries differ from those of the old parish. The ward had a population of 2,774 in 2011.

Geography

Topography

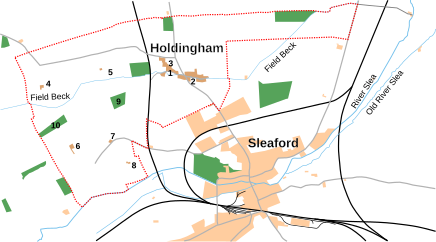

Holdingham is a settlement 0.9 miles (1.5 km) north of Sleaford, a market town in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire. The old hamlet clusters around and is bisected by Lincoln Road (B1518) immediately south of Holdingham Roundabout which connects Lincoln Road to the A17 and A15 roads.[2][3] A stream called Field Beck (also known as Holdingham Beck) runs east−west through the hamlet within a narrow, shallow valley. To the south of the hamlet is modern housing, which creates a contiguous urban area with Sleaford.[4][5]

Holdingham lies between approximately 20 and 30 meters above sea level.[2] The old hamlet on the west side of Lincoln Road is underlain by Jurassic mudstone belonging to the Blisworth Clay Formation, a group of sedimentary rocks formed 165–168 million years ago; this forms a narrow outcrop along Field Beck's shallow valley. The bedrock under the rest of the area (including the modern housing developments) is Cornbrash limestone belonging to the Great Oolite Group of Jurassic rocks formed 161–168 million years ago.[2][6] The soil belongs to the Aswarby series of brown, calcareous earth.[2] It is free-draining, loamy and lime-rich, suited for growing cereals and grasses[7] but classified as a nitrate vulnerable zone.[8]

Parish and ward boundaries

Holdingham gave its name to a civil parish which existed between 1866[9] (when it was separated from the ancient parish of New Sleaford) and 1 April 1974,[10] when it was merged into the current successor civil parish of Sleaford.[11][12] The parish boundaries, which contained the hamlet and adjacent fields and farm houses, were finally amended in 1882.[11]

Since 1998, Holdinham has also given its name to an electoral ward (Sleaford Holdingham) in the district of North Kesteven.[13] The ward's boundaries have been altered several times. As fixed in 2006,[14] they differed from those of the old civil parish by including the Jubilee Grove and Woodside Avenue housing estates, Sleaford Wood, Poplar Business Park and Sleaford Enterprise Park (all east of Lincoln Road); the ward boundaries also excluded most of the land south of the line between The Drove and Sumner's Plantation which had been in the former parish.[n 1] In 2021, the Stokes Drive and St Denys' Avenue housing estates (to the west of Lincoln Road) were transferred to the Sleaford Westholme ward.[15][16]

Climate

The British Isles experience a temperate, maritime climate with warm summers and cool winters.[17] Data from the weather station nearest to Holdingham (at Cranwell, 3 miles north-west), shows that the average daily mean temperature is 9.8 °C (49.6 °F); this fluctuates from a peak of 16.9 °C (62.4 °F) in July to 3.9 °C (39.0 °F) in January. The average high temperature is 13.7 °C (56.7 °F), though the monthly average varies from 6.7 °C (44.1 °F) in January and December to 21.8 °C (71.2 °F) in July; the average low is 5.9 °C (42.6 °F) which reaches its lowest in February at 0.8 °C (33.4 °F) and its highest in July and August at 12.0 °C (53.6 °F).[18]

| Climate data for Cranwell WMO ID: 03379; coordinates 53°01′52″N 0°30′13″W / 53.03117°N 0.50348°W; elevation: 62 m (203 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1930–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

32.9 (91.2) |

39.9 (103.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.6 (88.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.7 (3.7) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 48.1 (1.89) |

38.4 (1.51) |

36.3 (1.43) |

44.6 (1.76) |

48.4 (1.91) |

59.8 (2.35) |

53.5 (2.11) |

59.5 (2.34) |

50.5 (1.99) |

62.4 (2.46) |

56.6 (2.23) |

54.6 (2.15) |

612.6 (24.12) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.9 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 116.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 65.1 | 83.7 | 124.2 | 163.0 | 209.2 | 191.6 | 202.2 | 187.6 | 151.1 | 113.6 | 74.4 | 65.6 | 1,631.3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[20][21] | |||||||||||||

History

Prehistoric, Roman and early Saxon settlements

A Bronze Age flint scraper and two pottery sherds from the same period have been uncovered at Holdingham.[22] Lincoln Road, connecting Sleaford and Lincoln, may have Roman origins, although the stretch between Sleaford and Brauncewell (via Holdingham) could be prehistoric. East of the settlement is a suspected Roman villa and skeletons have been uncovered with Romano-British pottery to the south-west;[2] coins and pottery recovered in archaeological investigations date between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD.[23] Along with ditches and gullies, the remains of early and middle Anglo-Saxon enclosures and post-built buildings have been uncovered east of Holdingham Roundabout (on the sites where the McDonald's restaurant and the Furlong Way housing development have since been built); finds included sherds of pottery, much of it produced locally though some from as far away as Leicestershire. Animal bones, loom weights, querns, metal-working waste, remains of crops and domestic waste were also uncovered.[24] The site dwindled in size and was "largely abandoned" in the 9th century; it probably reverted to agricultural use and it is possible that the settlement shifted to the present location of the hamlet on the western side of Lincoln Road. Its decline may also reflect the growing importance of Sleaford.[25]

Later farming village

The word Holdingham derives from the personal name Hald and the Old English words -inga and -ham, together meaning "Homestead of Hald's family or followers", as the place name historian A. D. Mills puts it.[26] The place name scholars Kenneth Cameron and John Ingsley make him Halda and his followers the Haldingas.[27] Either way, this implies a pre-conquest origin, though the earliest record of the name does not occur until c. 1202.[28] Although not mentioned in the Domesday Book, it was probably a dependent part of the Bishop of Lincoln's manor in Sleaford.[29] In the mid-12th century, the Bishops of Lincoln encouraged trade at New Sleaford (as it became known); they granted it limited liberties and burgage tenure. An estate survey of 1258, however, shows that tenants in Holdingham held land described as tofts and bovates, implying that it remained a centre of demesne farming.[30][31] The arrangement of the manor's open fields around the settlement add credence to this, suggesting, as local historian Simon Pawley wrote, that Holdingham was "the agricultural focus" of the Bishop's estate at Sleaford.[32] By 1334, the settlement was valued at £2 16s. 3¼d.[33] It remained a part of the Bishop's estate until Bishop Holbeach alienated it to the Crown in 1540. Mary I granted it to Edward Clinton, Lord Clinton and later Earl of Lincoln, who sold it to Robert Carre in 1559. It passed through his family and then, by marriage, to the Earls (later Marquesses) of Bristol.[34]

In medieval and early modern times, the settlement was arranged into closes.[35] St Mary's Chapel served the inhabitants from at least 1340 (when it is first recorded) until around 1550, around which time it fell into ruin. Its location is unknown.[36] To the west, the land south of Newark Road was part of the Anna (or Annah) Common.[34][35][n 2] The earliest surviving map of Holdingham dates from 1776 and shows the arrangement of closes, surrounded by open fields (Town Furlong to the south, Waze Furlong to the far east and Walnut Tree Furlong to the east, immediately beneath the row of small closes that lined the drove to Sleaford Moor).[39] In 1794 the Marquess of Bristol enclosed the open fields; he had by far the largest stake in them, at c. 1,000 acres, against the combined 96 acres divided between seven other men. In order to compensate inhabitants with grazing rights, Lord Bristol allocated them land on Sleaford Moor, to the east of Holdingham.[40] The Vicar of Sleaford was allocated a farm on the Anna to compensate for the loss of his tithes.[41]

By the 16th century, the route through Holdingham was used by drovers bringing their cattle from Scotland down to London via Norfolk. The Green Dragon, a public house at Holdingham, sat on four acres of land which drovers used to put their cattle to pasture while they stopped there for a drink just before the tollgate at Sleaford. It was renamed The Jolly Scotchman in 1821, possibly because of this link.[42]

In 1825, Holdingham had eighteen houses and a number of tenements for the poor; together, these housed 25 families.[37] Although anciently a hamlet in the parish of New Sleaford, Holdingham appointed its own parish officers in the early 19th century.[37] In 1866, Holdingham was reorganised into its own civil parish (though the ecclesiastical parish boundaries remained unchanged);[43] at the next census in 1871, it had 27 inhabited houses, 31 families and a population of 143.[44] Over the next seventy years, the parish population stayed fairly static before declining slightly; there were only 75 people living in 22 houses in 1951.[45][46]

Modern developments

A petrol filling station had been built on Lincoln Road, just south of the hamlet, by at least the 1960s; in 1972, this was taken over by Hockmeyer Motors, who later replaced it with a modern filling station.[47][48][n 3] In 1975, Sleaford's eastern bypass opened, which included the construction of Holdingham Roundabout immediately north of the hamlet and at the intersection of the A15, Lincoln Road and the A17, the latter of which was diverted out of the town and east to Kirkby la Thorpe on a new road.[50] The town's western bypass was added in 1993, which diverted the A15 around Sleaford from Holdingham Roundabout south to Silk Willoughby.[51][52] In the early 1990s, a service station opened at Holdingham roundabout with a hotel and restaurant, and a fast food restaurant opened near the roundabout in 2001.[n 4]

From the 1930s onwards, Sleaford's urban area gradually encroached northwards along either side of Lincoln Road: the private North Parade development on the west was built in the 1930s and the interwar and postwar social housing on the east were built near Holdingham's parish boundaries.[n 5] The Marquess of Bristol still owned almost all of the agricultural land in the parish before the 1960s,[60] but then began selling it off, which allowed speculative development to take place around the town including at Holdingham.[61] Suburban housing on St Denys Avenue was built c. 1968,[62] north of the North Parade estate and within the parish boundaries.[59] The parish was merged with New Sleaford, Old Sleaford and Quarrington in 1974 to form the current Sleaford civil parish.[12][11] In the early 1970s, another speculative estate was built within the Holdingham boundaries adjoining the council housing on the east side of Lincoln Road.[n 6] The Woodside Avenue estate was also built in the late 1970s, adjoining the Jubilee Grove estate to the north-east.[63][64]

In 1987, the district council designated as development land sites between St Denys' Avenue and Holdingham village on the west side of Lincoln Road, and between Durham Avenue, the Woodside Avenue estate and Holdingham village on the east side.[65][66] These lands were developed for private housing in the 1990s and early 2000s, effectively making Holdingham part of Sleaford's contiguous urban area.[n 9] As the local historian Simon Pawley remarked in the late 1990s, Holdingham had "begun to look more like a suburb of Sleaford than a village in its own right" as a result of these developments.[76] In the early 2010s, further development took place,[n 10] followed over the next decade by almost 300 houses and a new nursing home at Holdingham Grange, east of the McDonald's and bounded to the north by the A17 bypass.[n 11] The care home opened in 2018.[83]

Future

The Sleaford Masterplan, produced in 2011 for North Kesteven District Council, designated large tracts of land between the existing housing and the A15 bypass as potential housing sites for the period to 2036.[84] In 2017, planning permission was granted to the Drove Landowners Partnership to build 1,400 homes, two schools, a hotel, a community centre and shops on this land, spanning from Holdingham to The Drove; they expected it to be built in phases, with completion in the early 2030s.[85][86]

Economy

Context

The Sleaford built-up area is the urban centre of the North Kesteven district,[87] and one of the district's centres of employment.[88] According to a local authority report, Sleaford is also "the main retail, service and employment centre for people living in the town and in the surrounding villages".[89] Retail, services and distribution make up 22% of the town's workforce.[90]

The public sector is the predominant form of employment in Sleaford civil parish; public administration, education and healthcare collectively account for 29% of the workforce.[91] Sleaford houses the headquarters of North Kesteven District Council,[92] as well as four primary schools and three secondary schools,[93] and is near the Royal Air Force bases at Cranwell, Digby and Waddington which are major employers in the district.[88]

Sleaford also includes one of the district council's three "strategic employment locations", Sleaford Enterprise Park,[88] which lies within the Sleaford Holdingham ward.[94] According to Google Maps, the enterprise park in 2020 housed at least 40 businesses, including a brewer, furniture maker, tarpaulin manufacturer, 12 retailers (including five vehicle dealerships), four wholesalers, a plant hire outlet, a publisher, three leisure services, eight skilled trades (including six vehicle repair shops), and other services. The Sleaford Household Waste Recycling Centre is also on the site. North of the Enterprise Park are outlets housing two wholesalers, a tool manufacturer, an electrician, a training centre and an energy supplier. Immediately adjacent but outside of the ward boundaries are the other business parks and industrial estates which collectively house over 60 more companies, including retailers, wholesalers, services and manufacturing concerns.[95]

Many of North Kesteven's residents also commute out of the district to work, including at Lincoln, Grantham and Newark-on-Trent.[88]

Workforce (Sleaford Holdingham ward)

According to the 2011 census, 74% of the Sleaford Holdingham ward's residents aged between 16 and 74 were economically active, compared with 70% for all of England. 66% were in employment, compared with 62% nationally. The proportion of full-time employment was relatively high, at 44% (against 39% nationally). The proportion of retirees was 14%, the same as the national rate. The proportion of long-term sick or disabled was 3%, slightly lower than England's 4%; 2% of people were long-term unemployed, the same rate as in all of England.[96][97]

The 2011 census revealed that the most common industry that the ward's residents worked in was wholesale and retail trade and the repair of motor vehicles (15%, comparable with England's population as a whole at 16%). Public administration and defence was overrepresented among the ward's population, accounting for 14% of workers compared with 6% nationally. The proportion of people working in manufacturing (12%) was also higher than in England as whole (9%). Human health and social work activities accounted for 12%, almost the same as the national rate. No other sectors accounted for more than 10% of the workforce, with the next highest being construction (8%), education (7%), accommodation and food services (7%) and transport and storage (6%). Professional and scientific activities were underrepresented (at 4% against 7% nationally). The proportion of people working in financial services (1%) was a quarter of the rate nationally.[96][97]

The census also showed that 9% of the working population were managers, directors or senior officials, and 11% were professionals, both lower than the figures for England as a whole (11% and 18% respectively); 12% were associate professionals or people employed in technical occupations, roughly in line with the national figure. A further 10% of people were in administrative or secretarial jobs, lower than in England (12%), while 13% were in skilled trades (higher than in England as a whole). Relative to England, similar proportions of residents worked in caring, leisure or other service occupations (9%) and sales and customer service jobs (8%), but there were higher rates of employment as process, plant and machine operatives (12% against 8% nationally) and in elementary occupations (16% compared with 11% nationally).[96][97] There was wide variation within the ward; 20% of workers on the Stokes Drive estate were in professional jobs, whereas the rate was 3% on some parts of the Jubilee Grove estate; in the latter areas, up to 24% of workers were in elementary occupations, compared with 10% of workers on the Stokes Drive estate.[98]

The census also showed that 23% of residents have no qualifications, in line with the national figure (23%); 20% have a qualification at Level 4 (Certificate of Higher Education) or above, which is a much lower rate than the 27% nationally.[96][97]

Demographics

Population change

There were 20 families living in Holdingham in 1563, according to the diocesan returns of worshippers.[99] This had increased to 25 families in 1825.[37] The 1801 census recorded 113 residents, which rose to 198 in 1841.[99] This fell to 143 in 1871,[100] 120 in 1881 and 89 in 1891, before increasing slightly to 95 in 1901. It rose slightly to 101 in 1921 and 107 ten years later, but had dropped back to 75 by 1951.[45] The parish was merged into Sleaford in 1974.[11][12] Since the 1990s, the hamlet has been incorporated into the built-up area of Sleaford.[76] The modern ward of Sleaford Holdingham (which has different boundaries to former parish) had a total population of 2,774 in 2011;[96] this accounted for 16% of the population of Sleaford (17,671).[101]

Ethnicity, country of origin and religion

According to the 2011 census, the population of Sleaford Holdingham ward was 98% white, 1% Asian or Asian British and 1% mixed or multi-ethnic, with very few black, African, Caribbean or black British people or people of other ethnicities. This implies that the ward was more ethnically homogenous than England as a whole, where 85% of people are white, 8% Asian or Asian British, 2% mixed, 4% black, African, Caribbean or black British, and 1% other. Around 94% of the ward's population were white British and 3% were classed as "other white", whereas 80% of England's population was white British in 2011. Approximately 93% of the ward's residents were born in the United Kingdom (88% in England), 0.4% in Ireland, 4% elsewhere in the European Union (3% in post-2001 accession states), and 3% in other countries; this made the population much more UK-born than England as a whole, where 86% of the population were born in the UK, 1% in Ireland, 4% in the rest of the EU and 9% elsewhere. In 96% of households, all people aged over 16 had English as their first language.[96][97]

In the 2011 census, 69% of Sleaford Holdingham's population stated that they were religious (similar to England's rate of 68%) and 24% stated that they did not follow a religion (the remaining 7% not stating a religion). 68% of the population were Christian, with approximately 40 people belonging to other religions; the proportion of Christians was higher than in England, where 59% are Christian, 5% are Muslim and 4% belong to other religions.[96][97]

Household composition, age, health and housing

In 2011, 49% of the ward's population were male and 51% female. There were 1,148 households in the ward: 26% single-person households, 68% one-family households, and 6% other types; the rate of single-person households was below England's level (30%) and the proportion of one-person households was higher than in England generally (62%). The census showed that 37% of households included a married couple or a couple in a same-sex civil partnership (higher than England's 33%), while 12% comprised a cohabiting couple and 11% a lone parent, compared to 10% and 11% nationally respectively. 34% of households included dependent children (almost half of those were in households with married couples), higher than the national rate of 34%. Of all the residents aged over 16, 50% were married, 30% were single, 11% divorced or formerly in a civil partnership, 6% were widowed, 3% separated and 0.2% were in a same-sex civil partnership; this compared with 47%, 34%, 9%, 7%, 3% and 0.2% nationally, respectively.[96][97]

The mean age in the ward in the 2011 census was 38.2 years and the median 39; the latter was slightly younger than England's national average. 22% of the ward's residents were under 16 (compared to 19% in England), while 15% were aged 65 and over (slightly below England's 16%). 82% of the population reported being in very good or good health (very similar to England's 82% rate) and an additional 13% reported being in fair health, the same as the national rate; 83% reported that their day-to-day activities were not limited, only slightly above England's rate of 82%.[96][97]

According to the 2011 census, a slightly higher proportion of the ward's residents own their own homes with or without a mortgage (65%) than in England as a whole (63%). At 21%, a greater proportion of people in the ward socially rent (the figure is 18% nationally); about three quarters of these people rent from the local authority. 13% of residents rent privately; this is lower than in England as a whole (17%). 98% of the dwellings in the ward were whole houses or bungalows, with only 2% being flats, maisonettes or apartments; most of the dwellings were detached (41%) or semi-detached (42%), with a further 15% being terraced.[96][97]

Deprivation

For measuring deprivation, the Sleaford Holdingham ward is divided into two statistical units called Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs). The 2010 Indices of Multiple Deprivation showed that the ward contains both the second-most deprived and sixth-least deprived LSOAs in North Kesteven (out of 60 such statistical units).[102] The data from the 2019 update showed that there remained a disparity between the two areas; the LSOA which covered all the lands east of Lincoln Road (excluding part of the Durham Avenue estate and all of the Furlong Way estate) ranked among the 40% most deprived LSOAs nationally. By contrast, the LSOA covering the rest of the ward ranked among the 20% least deprived areas in the country.[103]

Government and politics

Local government

Holdingham was a hamlet in the ancient parish of New Sleaford, part of Kesteven's Flaxwell wapentake. It was incorporated into Sleaford Poor Law Union.[11] In 1866, Holdingham was created as a separate civil parish.[11] The Public Health Act 1872 established urban sanitary districts (USD)[104] and Holdingham became part of the Sleaford USD, which in turn was reorganised into Sleaford Urban District (UD) in 1894.[11] Sleaford UD was abolished by the Local Government Act 1972 and, by statutory instrument, Sleaford civil parish became its successor, thus merging Quarrington, New Sleaford, Old Sleaford and Holdingham civil parishes.[12]

Since 1998, Holdingham has fallen within the Sleaford Holdingham wards in Sleaford Town Council and North Kesteven District Council;[105][106][15] it is represented by two councillors on the town council and one councillor in the district.[15] The settlement also falls within the Lincolnshire County Council electoral division of Sleaford, which is represented by one councillor.[106][107][108]

National and European politics

Before 1832, Holdingham was in the Lincolnshire parliamentary constituency. In 1832, the Reform Act divided Lincolnshire. Holdingham was placed in the South Lincolnshire constituency that elected two members to parliament. The constituency was abolished in 1885 and Holdingham was in the new Sleaford (or North Kesteven) constituency. It merged with the Grantham seat in 1918.[109] In 1995, Holdingham was reorganised into Sleaford and North Hykeham, effective from the 1997 general election.[110] The member returned in 2019 for Sleaford and North Hykeham was the Conservative candidate Caroline Johnson, who has been the sitting MP since 2016.[111]

Lincolnshire elected a Member of the European Parliament from 1974 until 1994,[112][113] and then became part of the Lincolnshire and Humberside South constituency until 1999;[114] it then elected members as part of the East Midlands constituency until the United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union in 2020.[115]

Transport

The A17 road from Newark-on-Trent to King's Lynn bypasses Sleaford from Holdingham Roundabout to Kirkby la Thorpe.[4] It ran through the town until the bypass opened in 1975.[50] The Holdingham roundabout connects the A17 to the A15 road from Peterborough to Scawby.[4] It also passed through Sleaford until 1993, when its bypass was completed.[51]

The nearest railway station is at Sleaford, which is a stop on the Peterborough to Lincoln Line and the Poacher Line, from Grantham to Skegness.[116] Grantham, roughly 14+3⁄4 miles (23.7 kilometres) by road and two stops on the Poacher Line, is a major stop on the East Coast Main Line. Trains from Grantham to London King's Cross take approximately 1 hour 15 minutes.[117][118]

Education

The Sleaford Holdingham Ward does not contain any schools or other educational facilities. Education is provided in Sleaford, where there are four primary schools. The nearest are Church Lane School (on Church Lane) and Our Lady of Good Counsel Roman Catholic Primary School (on the Drove); there is also the William Alvey Church of England Primary School on Eastgate and St Botolph's Church of England Primary School in Quarrington. There are also primary schools in the nearby villages of Leasingham, Kirkby la Thorpe and North Rauceby.[119]

There are three secondary schools in Sleaford, each with sixth forms: Carre's Grammar School, a boys' grammar school and selective academy; Kesteven and Sleaford High School, a selective academy and girls' grammar school; and St George's Academy (a mixed non-selective comprehensive school and academy).[119] The grammar schools are selective and pupils are required to pass the Eleven plus exam.[120] St George's is not academically selective.[121] The co-educational Sleaford Joint Sixth Form consortium allows pupils to choose sixth form courses taught at all three schools regardless of which one they are based at.[122]

Religion

Holdingham had a chapel in the Middle Ages, which was last in use in the 1550s; it has subsequently disappeared and its location is not known with certainty.[123] As of 2020, Sleaford provides the focus for religious worship. Anglican services normally take place at St Denys' Church, by the town's market place; Holdingham falls within the ecclesiastical parish of New Sleaford.[124] There is a Catholic church (Our Lady of Good Counsel) on Jermyn Street.[125] Sleaford United Reformed Church and the Sleaford Community Church merged in 2008 to form the Sleaford Riverside Church, which meets at premises on Southgate.[126] Sleaford Methodist Church is located on Northgate.[127] New Life Church Ministries have a centre on Mareham Lane.[128] The Salvation Army has a chapel on West Banks.[129] The Sleaford Muslim Community Association has a prayer hall on Station Road.[130] Sleaford Spiritualist Church operates on Westgate.[131]

Historic buildings

There are seven listed buildings in Holdingham. Three entries are in the hamlet itself: the 17th- or early-18th-century cottage 1, Holdingham;[132] the 18th-century building at 12, Holdingham;[133] and the mid-18th-century buildings at 13 and 14, Holdingham.[134] To the west of the settlement is the 17th- or early 18th-century Anna House Farmhouse and outbuildings.[135][136] To the farthest west in the former parish boundaries are the late-18th-century Holdingham Farmhouse[137] and adjoining mill buildings.[138] In addition to the listed buildings, several others are recorded as having "local interest", including nos. 7–11, Holdingham.[135]

Notable residents

Holdingham gave its name to Richard de Haldingham and Lafford (died 1278) the donor and possible author of the Hereford Mappa Mundi.[139]

References

Notes

- ^ "Map Referred to in the District of North Kesteven (Electoral Changes Order) 2006 Sheet 2 of 2" (PDF). Local Government Boundary Commission for England. Retrieved 28 May 2024. Compare with Ordnance Survey. 6-Inch Map of England and Wales. Lincolnshire Sheets CVI.NW and CVI.NE. Revised 1947 and published 1950. Retrieved via the National Library of Scotland on 25 May 2024.

- ^ The clergyman Rev. Richard Yerburgh suggested that this name derived from the Latin word Hamma, meaning home close or meadow.[37] The Victorian clergyman and antiquarian Edward Trollope speculates that it referred instead to anchorage.[38]

- ^ The garage's owners opened a café in a converted barn adjacent to the site in 2018.[49]

- ^ In 1990, Trusthouse Forte UK were granted permission to build a hotel, services and a petrol station on a site on the north-west;[53] Little Chef opened there in 1991, joined by a Travelodge.[54][55][56] McDonald's opened a restaurant on the site to the south-east in 2001.[57][58]

- ^ Pawley 1996, p. 120 gives the dates of the interwar North Parade and Jubilee Grove developments. For the post-war developments, see North Kesteven District Council 2010, fig. 8 (overleaf from page 5). Compare with the parish boundaries shown in a 1970 Ordnance Survey map of the area.[59]

- ^ This was finished by 1975.[63]

- ^ [67][68][69][70]

- ^ A further 16 homes were fully approved in 2002.[71]

- ^ Planning permission was granted in 1987–91 for private housing developments off Durham Avenue on the east of Lincoln Road totalling 212 homes[n 7][n 8] and most of the estate was complete by 1996.[72] Full planning permission was granted to developers for the construction of 174 houses on the west side of Lincoln Road in 1991 and 1995,[73][74] and these houses were mostly finished by late 2001.[75]

- ^ In 2008 Nottingham Community Housing Association was granted permission to build 97 houses on the greenfield site east of McDonalds,[77] which was largely complete by 2011.[78]

- ^ Outline planning permission was granted to a private house-builder in 2014 for the erection of 290 houses and a 70-bed nursing home on land to the east of this development, which was completed over the late 2010s and early 2020s.[79] the number was reduced to 286 three years later.[80] The rest of the housing development, known as Holdingham Grange,[81] was partially complete as of 2019.[82]

Citations

- ^ Derived from Ordnance Survey. 6-Inch Map of England and Wales. Lincolnshire Sheets CVI.NW and CVI.NE. Revised 1947 and published 1950. Retrieved via the National Library of Scotland on 25 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Cope-Faulkner 2006, p. 2.

- ^ "Holdingham". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 30 August 2015. Note: select "Civil Parishes or Communities" and search for "Sleaford, Lincolnshire".

- ^ a b c "Holdingham". Bing Maps. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ The name "Holdingham Beck" is used by Cope-Faulkner 2006, p. 1.

- ^ "UK Geology or Earthquake Maps". British Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Soilscapes" (interactive map). Cranfield Soil and Agrifood Institute. Cranfield University. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Check for Drinking Water Safeguard Zones and NVZs". Environment Agency. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Relationships and changes Holdingham CP/Hmlt through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. University of Portsmouth and Jisc. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Sleaford & East Kesteven Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Youngs 1991, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d The Local Government (Successor Parishes) Order 1973 (1973, no. 1110). Retrieved 28 May 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Created through The District of North Kesteven (Parishes and Electoral Changes) Order 1998. Retrieved 28 May 2024 - via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ The District of North Kesteven (Electoral Changes) Order 2006 (2006, no. 1405), s. 5. Retrieved 28 May 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ a b c The North Kesteven (Electoral Changes) Order 2021 (2021, no. 1052). Retrieved 28 May 2024 via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Map referred to in the North Kesteven (Electoral Changes) Order 2021" (PDF). Local Government Boundary Commission for England. 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Climate of the World: England and Scotland". Weather Online. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Cranwell 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Cranwell 1991–2020 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Minimum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Bronze Age Finds from Land at Lincoln Road, Holdingham (HER Number 64183)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "Romano-British Features on Land off Lincoln Road, Holdingham (HER Number 64185)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "Early to Middle Saxon Settlement Remains on Land at Holdingham, Sleaford (HER Number 64180)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Cope-Faulkner 2006, pp. 2, 15.

- ^ Mills 2011, p. 242.

- ^ Cameron & Ingsley 1998, p. 64.

- ^ Cope-Faulkner 2006, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Mahany & Roffe 1979, p. 13.

- ^ Mahany & Roffe 1979, p. 18.

- ^ Hosford 1968, p. 28.

- ^ Pawley 1996, pp. 17, 28–29.

- ^ "Settlement of Holdingham (HER Number 63670)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ a b Trollope 1872, pp. 118–119, 181.

- ^ a b Pawley 1996, p. 62.

- ^ "Site of St Mary's Chapel, Holdingham (HER Number 60400)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Yerburgh 1825, p. 90.

- ^ Trollope 1872, p. 181.

- ^ Cope-Faulkner 2000, fig. 3.

- ^ Pawley 1996, p. 63.

- ^ Trollope 1872, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Brand & Pawley 2024, p. 40

- ^ "Holdingham Hmlt/CP". A Vision of Britain through Time. University of Portsmouth and Jisc. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Census Office 1872, p. 226.

- ^ a b "Total Population: Holdingham". A Vision of Britain through Time. University of Portsmouth and Jisc. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Holdingham Hmlt/CP: Housing: Total Houses (Table View)". A Vision of Britain through Time. University of Portsmouth and Jisc. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Home". Hockmeyer Motors. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016.

- ^ "About Us". Hockmeyer Motors. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012.

- ^ Hubbard, Andy (3 July 2019). "New Coffee Shop for Sleaford Is a Truly Family Concern". Sleaford Standard. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b "The £2m Bargain". Sleaford Standard. 4 April 1975. p. 9. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive..

- ^ a b "Traffic Joy as Bypass Opens". Sleaford Standard. 23 September 1993. p. 6. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bypass Named". Sleaford Standard. 17 September 1992. p. 14. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: N/57/0777/90". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Sleaford". Little Chef. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020.

- ^ They were granted permission to erect a sign on the site in 1991: "Planning – Application Summary: 90/1181". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Opening Raises £180". Sleaford Target. 5 September 1991. p. 1. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 01/0146/RESM". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Burger Date for Gruff". Sleaford Standard. 28 June 2001. p. 1. Retrieved 21 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey. 1:2,500 Map of England and Wales. Published 1970. Retrieved 1 October 2020 – via Old-Maps.co.uk.

- ^ Cope-Faulkner 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Pawley 1996, p. 122

- ^ "Cattle Market Noise 'Intolerable'". Sleaford Standard. 25 October 1968. p. 15. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "200 More Homes on the Way". Sleaford Standard. 27 November 1975. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Names". Sleaford Standard. 25 January 1979. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Day 1987, proposals map.

- ^ "Town's District Plan Adopted". Lincolnshire Echo. 2 October 1987. p. 5. Retrieved 24 May 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: N/57/0558/87". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: N/57/1453/88". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: N/57/0554/89". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 91/0941/FUL". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 02/0019/FUL". Planning Portal. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ See 1:10,000 Ordnance Survey map dated 1996.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 91/0166/FUL". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 95/0107/FUL". Planning Portal. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Satellite imagery dated 31 December 2001 and captured by Infoterra and Bluesky, retrieved via Google Earth Pro.

- ^ a b Pawley 1996, p. 122.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 07/1051/FUL". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Google Street View imagery dated March 2011 for the coordinates 53.0115174, −0.422339. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 12/1022/OUT". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning – Application Summary: 17/0866/VARCON". Planning Online. North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Nearly 500 People Register for First Phase of New Sleaford Housing Development". Sleaford Standard. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Historical satellite imagery dated 29 March 2019 retrieved through Google Earth Pro.

- ^ "CQC Says Care Home 'Requires Improvement'". Sleaford Standard. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Gillespies 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Barker, Sarah (16 February 2017). "Revised Plans Submitted for 1,400 Homes, Schools, Restaurant and Hotel in Sleaford". The Lincolnshire Reporter. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Planning Permission Granted for 1,400 New Home Development for Sleaford". Lincolnshire World. 24 March 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Ekosgen & Turley Economics 2015, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d North Kesteven District Council 2024, p. 10.

- ^ Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee 2013, p. 106.

- ^ Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee 2013, pp. 104, 106.

- ^ "Contact Us". North Kesteven District Council. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Search Results". Ofsted. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ The modern ward boundaries can be found by locating Holdingham and toggling the "District Wards" layer at "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Sleaford". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Local Area Report: Sleaford Holdingham". Nomis: Official Labour Market Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Local Area Report: England". Nomis: Official Labour Market Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Census". Datashine. University College London and the Economic and Social Research Council. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Settlement of Holdingham (HER Number: 63670)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Census Office 1873, p. 654

- ^ Calculated from the parish's total population recorded at "Local Area Report: Sleaford Parish". Nomis: Official Labour Market Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ North Kesteven District Council 2014, pp. 17–18

- ^ "Indices of Deprivation 2019 Explorer". Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Status Details for Urban Sanitary District", Vision of Britain (University of Portsmouth and Jisc). Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ The District of North Kesteven (Parishes and Electoral Changes) Order 1998 (1998, no. 2338), schedule 1. Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ a b "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Councillors", Sleaford Town Council. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ The County of Lincolnshire (Electoral Changes) Order 2000, schedule. Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Youngs 1991, pp. 265, 824, 826

- ^ The Parliamentary Constituencies (England) Order 1995 (1995, no. 1626), article 2 and schedule. Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Dr Caroline Johnson". UK Parliament. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ The European Assembly Constituencies (England) Order 1978 (1978, no. 1903). Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ The European Assembly Constituencies (England) Order 1984 (1984, no. 544). Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ The European Parliamentary Constituencies (England) Order 1994. Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ European Parliamentary Elections Act 1999. Retrieved 2 June 2024 – via Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Regional Timetable 7. East Midlands Trains. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ "Route (Road): Sleaford, Lincolnshire, UK, to Grantham Station, Station Road, Grantham". Google Maps. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Timetable: Sunday 10 December 2023 to Saturday 1 June 2024 (PDF). LNER. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Search Results". Ofsted. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "The 11-Plus". Lincolnshire Consortium of Grammar Schools. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ St George's Academy 2019, pp. 4–5.

- ^ "Home". Sleaford Joint Sixth Form. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Site of St Mary's Chapel, Holdingham (HER Number 60400)". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "St Denys'". A Church Near You. The Archbishops' Council. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Home". Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, Sleaford. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "History". Sleaford Riverside Church. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Sleaford". Sleaford Methodist Circuit. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Home". New Life Church Ministries. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Sleaford". The Salvation Army. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "First Mosque Open Day Proves Popular in Sleaford". Sleaford Standard. 10 March 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Sleaford Spiritualist Church". Spiritualists' National Union. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "1, Holdingham (List Entry No. 1062148 (1062148)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "12, Holdingham (List Entry No. 1360439) (1360439)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "13 and 14, Holdingham (List Entry No. 1168227) (1168227)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Anna House Farmhouse (List Entry No. 1168217) (1168217)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Outbuildings to North of Anna House Farmhouse (List Entry No. 1062149) (1062149)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Holdingham Farmhouse (List Entry No. 1062150) (1062150)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Holdingham Farmhouse (List Entry No. 1360440) (1360440)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Ramsay, Nigel (September 2004). ""Holdingham [Haldingham], Richard of"". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37891. Retrieved 5 October 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Bibliography

- Brand, Anthony; Pawley, Simon (2024), Celebrating Fifty (PDF), Sleaford: Sleaford Town Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2024.

- Cameron, Kenneth; Ingsley, John (1998), A Dictionary of Lincolnshire Place-Names, Nottingham: English Place Name Society, ISBN 9780904889581.

- Census Office (1872), Census of England and Wales, 1871: Population Tables: Area, Houses and Inhabitants, vol. 1, London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode.

- Census Office (1873), Census of England and Wales, 1871: General Report, vol. 4, London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode.

- Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee (2013), Central Lincolnshire Local Plan: Core Strategy: Partial Draft Plan for Consultation: Area Policies for Lincoln, Gainsborough and Sleaford, Lincoln: Central Lincolnshire Joint Planning Unit, archived from the original on 21 May 2024.

- Cope-Faulkner, Paul (2000), Desk-Top Assessment of the Archaeological Implications of Proposed Development of Land Adjacent to Lincoln Road, Holdingham, Sleaford, Lincolnshire (PDF), APS Report, vol. 192/00, Heckington: Archaeological Project Services, doi:10.5284/1014209, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2023.

- Cope-Faulkner, Paul (2006), Archaeological Evaluation on Land at Lincoln Road, Holdingham, Sleaford, Lincolnshire (PDF), APS Report, vol. 110/06, Heckington: Archaeological Project Services, doi:10.5284/1015439, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2023.

- Day, R. A. (1987), Sleaford Interim District Plan: Draft Written Statement, Sleaford: North Kesteven District Council.

- Ekosgen; Turley Economics (2015), Central Lincolnshire Economic Needs Assessment: Final Report (PDF), Manchester: Turley, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2021.

- Gillespies (2011), Sleaford Masterplan: Final Report (PDF), Leeds: Gillespies, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2021.

- Hosford, W. H. (1968). "The manor of Sleaford in the thirteenth century". Nottingham Medieval Studies. 12: 21–39. doi:10.1484/J.NMS.3.37.

- Mahany, Christine M.; Roffe, David (1979), Sleaford, Stamford: South Lincolnshire Archaeological Unit, ISBN 0906295025

- Mills, A. D. (2011). "Holdingham". In Mills, A. D. (ed.). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780191739446.

- North Kesteven District Council (2010), Sleaford Masterplan Scoping Report: Final Report, Sleaford: North Kesteven District Council, archived from the original on 17 September 2014.

- North Kesteven District Council (2014), The State of the District (PDF), Sleaford: North Kesteven District Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2020

- North Kesteven District Council (2024), North Kesteven District Profile February 2024 (PDF), Sleaford: North Kesteven District Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2024.

- Pawley, Simon (1996), The Book of Sleaford, Baron Birch for Quotes Ltd., ISBN 0860235599.

- St George's Academy (2019), St George's Academy Admissions Policy, 2019–2020 (PDF), Sleaford: St George's Academy, pp. 4–5, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2024, retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Trollope, Edward (1872), Sleaford and the Wapentakes of Flaxwell and Ashwardhurn, London: W. Kent & Co., OCLC 228661584.

- Yerburgh, Richard (1825), Sketches, Illustrative of the Topography and History of New and Old Sleaford, in the County of Lincoln, and Several Places in the Surrounding Neighbourhood, Sleaford: James Creasey.

- Youngs, Frederic A. (1991), Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, vol. 2, London: Royal Historical Society, ISBN 978-0861931279.