Hoda Afshar

Hoda Afshar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1983 (age 40–41) |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Known for | documentary photography |

| Notable work | Remain (2018) |

| Awards | National Photographic Portrait Prize (2015), Bowness Photography Prize (2018) |

| Website | hodaafshar |

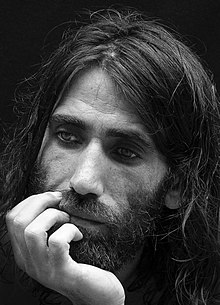

Hoda Afshar (born 1983) is an Iranian documentary photographer who is based in Melbourne. She is known for her 2018 prize-winning portrait of Kurdish-Iranian refugee Behrouz Boochani, who suffered a long imprisonment in the Manus Island detention centre run by the Australian government. Her work has been featured in many exhibitions and is held in many permanent collections across Australia.

Since 2019 and as of 2023 Afshar teaches at the Victorian College of the Arts and Photography Studies College in Melbourne.[1][2]

Early life and early education

Afshar was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1983,[1] four years after the Iranian Revolution.[3]

Initially hoping to study theatre and become an actor, but she was only granted her second choice, photography, at university.[3] She earned a bachelor's degree in fine art (photography) with first class honours[2] at the Azad University of Art and Architecture in Tehran.[1] During her studies and subsequently, she photographed many of her friends' theatre performances, coming to realise that photography was essentially theatrical too.[3]

Life and work

Her first project, in 2005, was a series of black and white photographs documenting Tehran's underground parties called Scene, but she could not show them in public.[1] From 2005 to 2006, Afshar worked as a photojournalist for Hamvatan newspaper in Tehran.[2]

She moved to Australia in 2007,[1] and in the same year completed a course at University of Technology Sydney, "Photojournalism Essential". In 2009 she completed a fine art diploma in photography and sculpture at the Meadowbank TAFE in Sydney.[2]

From 2013 to 2021 Afshar lectured at the Photography Studies College in Melbourne.[2]

Her first solo exhibition, Behold (2017, at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne), comprised a set of grainy photographs of men in a gay bathhouse taken in Iran in 2016.[3][4]

Afshar's two-channel video work, Remain (2018), includes spoken poetry by Kurdish-Iranian refugee Behrouz Boochani and Iranian poet Bijan Elahi. Afshar describes her method as "staged documentary", in which the men on the island are able to "re-enact their narratives with their own bodies and [gives] them autonomy to narrate their own stories". The video was shown as part of the Primavera 2018 exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, from 9 November 2018 to 3 February 2019.[5][6][7] One of the photographs of Boochani taken for this project won the Bowness Photography Prize.[8][9] This portrait, along with several others taken as part of the Remain project, are held by the Art Gallery of New South Wales.[10]

In 2019 Afshar completed her PhD in creative arts at Curtin University, with the subject of her thesis being "images of Islamic female identity".[1][2] In 2019 and Afshar started teaching at the Victorian College of the Arts and Photography Studies College in Melbourne.[1][2]

Afshar was the subject of a Compass program on ABC Television in 2019.[11]

Afshar's book Speak the Wind (2021) documents the landscapes and people of the islands of Hormuz, Qeshm, and Hengam, in the Persian Gulf off the south coast of Iran.[12][13] She got to know some of the people there, travelling there frequently over the years, and they told her about the history of the place. She said that "their narrations led the project", and she explores "the idea of being possessed by history, and in this context, the history of slavery and cruelty".[14]

In March 2021, an exhibition of Afshar's portraits of nine whistleblowers was mounted at St Paul's Cathedral in Melbourne, in an exhibition named Agonistes (after the Greek word agonistes, meaning a person engaged in a struggle).[1][15]

From September 2023 to January 2024, the Art Gallery of New South Wales mounted an exhibition of Afshar's work over the past decade, A Curve is a Broken Line.[16][17] It contained several of her earlier works, along with a series of 12 large photographs commissioned by AGNSW, In Turn. The photos featured four Iranian Australian women plaiting one another's hair, and first holding a white dove before releasing it. This is based on a kind of ritualistic practice among Kurdish female fighters before setting out to fight Islamic State. The photographs are a response to the killing of Mahsa Jina Amini in Iran in September 2022.[3] A book of the same name was published to accompany the exhibition.[18]

She is a board member of the Centre for Contemporary Photography.[19][2]

Practice and themes

Afshar says that her work explores how photographs may be "used or misused by power systems create certain hierarchies between people"; and that "[documentary photography] is a visual language that has been formed and established through the lens of colonisation".[1] Her early understanding of photography as a theatrical art informs her practice, and she collaborates with her subjects, whom she sees as "actors", in a way that gives them agency.[3]

Awards and recognition

- Moran Contemporary Photographic Prize (2015), finalist for Dog's Breakfast[20]

- National Photographic Portrait Prize (2015), winner for Portrait of Ali[21]

- Bowness Photography Prize (2017), finalist for Untitled #1[22][23]

- Sotheby's Australia People's Choice Award (2018), winner for Portrait of Behrouz Boochani, Manus Island[9]

- Bowness Photography Prize (2018), winner for Portrait of Behrouz Boochani, Manus Island[9]

- Olive Cotton Award for Photographic Portraiture (2019), finalist, for Portrait of Shamindan & Ramsiyar Manus Island[24]

- Ramsay Art Prize (2021), Art Gallery of South Australia; finalist[25][26] and People's Choice Prize, for Agonistes[27]

- Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship (2021), an award of A$160,000 given to mid-career creatives and thought leaders[28]

Publications

- Speak the Wind. London: Mack, 2021. With an essay by Michael Taussig. ISBN 978-1-913620-18-9.

Selected exhibitions

Solo

- Behold (2017), Centre for Contemporary Photography, Fitzroy, Melbourne[4]

- Remain (2018–2019), consisting of a video and a series of black-and-white portraits, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney;[1] University of Queensland Art Museum[29]

- Agonistes (February–March 2021), St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne[30]

- Speak the Wind (April–May 2022), Monash Gallery of Art, Melbourne. One of a series of official exhibitions of PHOTO 2022: International Festival of Photography, taking place in Melbourne and regional Victoria[31]

- A Curve is a Broken Line (September 2023 – January 2024) Art Gallery of New South Wales[16]

Group

- Primavera (2018), Museum of Contemporary Art Australia[32]

- Enough خلص Khalas: Contemporary Australian Muslim Artists (2018), UNSW Galleries[33]

- Women in Photography 2019: Remedy for Rage (2019), Objectifs[34]

- The Shouting Valley (2019), Gus Fisher Gallery,[35] (2020) The Physics Room[36]

- Just Not Australian (2019), Artspace Visual Arts Centre[37]

- Defining Place/Space: Contemporary Photography from Australia (2019), Museum of Photographic Arts[38]

- Civilization: The Way We Live Now (2019), National Gallery of Victoria[39][40]

- Refracted Reality (2020), Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts[41]

- f_OCUS (2020), Counihan Gallery[42]

- The Burning World (2020), Bendigo Art Gallery[43]

Collections

Afshar's work is held in the following permanent collections:

- National Gallery of Victoria: 8 works (as of 27 December 2024)[44]

- Monash Gallery of Art: 8 prints (as of 27 December 2024)[45]

- Art Gallery of New South Wales: 17 prints (as of 27 December 2024)[46]

- Monash University Museum of Art (Behold #1, Behold #6, and Behold #12)[47]

- University of Queensland Art Museum (Remain)[29]

- Murdoch University Art Gallery: (Westoxicated #7, Westoxicated #9, Westoxicated #3, Westoxicated #1, Westoxicated #5, and Westoxicated #4)[48]

- Buxton Contemporary (University of Melbourne) (Westoxicated #1, Westoxicated #2, Westoxicated #4, Westoxicated #5, Westoxicated #6, Westoxicated #7, and Westoxicated #9)[49]

- Deakin University Art Collection[50]

- Art Gallery of Western Australia (Remain)[51]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Reich, Hannah (6 March 2021). "Hoda Afshar documents Australian government whistleblowers in new photography and film project". ABC News. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "CV". Hoda Afshar. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Dow, Steve (7 September 2023). "Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line". The Monthly. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ a b "The hidden lives of gay men in the Middle East – in pictures". the Guardian. 27 March 2018. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Robson, Megan (6 November 2018). "Why is identity important today?". MCA. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Jefferson, Dee (3 February 2019). "These Australian artists are making waves with work that explores the complex, contested issue of identity". ABC News. Photography by Teresa Tan. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore, Clarissa (13 November 2019). "From Manus Island to sanctions on Iran: the art and opinions of Hoda Afshar". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Boochani, Behrouz (24–30 November 2018). "This human being". No. 232. Translated by Omid Tofighian. The Saturday Paper. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "2018 William & Winifred Bowness Photography Prize". Monash Gallery of Art. 2018. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Behrouz Boochani – Manus Island, 2018, Remain by Hoda Afshar". Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Boerne, Deborah (14 July 2019). "The Eyes Have It". Compass. ABC (Australian TV channel). Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Hoda Afshar's Speak The Wind | The Brooklyn Rail". brooklynrail.org. 30 July 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Colberg, Jörg (16 August 2021). "Speak The Wind". Conscientious Photography Magazine. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Grieve, Michael (19 July 2021). "Hoda Afshar captures the wind and rituals of the islands in the Strait of Hormuz". 1854 Photography. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "From Behrouz Boochani to Bernard Collaery: Photographer Hoda Afshar points lens at whistleblower". Sydney News Today. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Hoda Afshar". Art Gallery of NSW. 30 August 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line". Australian Arts Review. 2 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Brendan McCleary on Hoda Afshar's A Curve is a Broken Line". Photo Australia. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Team & Board". ccp.org.au. Centre for Contemporary Photography. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "2012 Photographic Prize: Open - finalists". moranprizes.com.au. Moran Arts Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Portrait of Ali, 2014 by Hoda Afshar". portrait.gov.au. National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "2017 William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize". mga.org.au. Monash Gallery of Art. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ William and William Bowness Photography Prize (PDF). Monash Gallery of Art. 2017. p. 66. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ 2019 Olive Cotton Award For Photographic Portraiture (PDF). Tweed Regional Gallery. June 2019. p. 6. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Keen, Suzie (22 April 2021). "2021 Ramsay Art Prize finalists announced". InDaily. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Hoda Afshar". AGSA - The Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Ramsay Art Prize 2021". AGSA - The Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ "Past Award Recipients". Sidney Myer Fund & The Myer Foundation. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Hoda Afshar: Remain". University of Queensland Art Museum. 14 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Burke, Kelly (10 February 2021). "From Behrouz Boochani to Bernard Collaery: photographer Hoda Afshar turns her lens on whistleblowers". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Speak the Wind". MGA: the Australian home of photography. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Primavera 2018: Young Australian Artists". mca.com.au. Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Enough خلص Khalas: Contemporary Australian Muslim Artists". unsw.edu.au. UNSW Sydney Art & Design. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Women in Photography 2019: Remedy for Rage". objectifs.com.sg. Objectifs. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "The Shouting Valley: Interrogating the Borders Between Us". gusfishergallery.auckland.ac.nz. Gus Fisher Gallery. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "The Shouting Valley: Interrogating the Borders Between Us". physicsroom.org.nz. The Physics Room. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Just Not Australian". artspace.org.au. Artspace Gallery. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Defining Place/Space: Contemporary Photography from Australia". mopa.org. Museum of Photographic Arts. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Civilization: The Way We Live Now". ngv.vic.gov.au. National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Civilization: The Way We Live Now - Artwork Labels (PDF). National Gallery of Victoria. p. 52. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Refracted Reality". pica.org.au. Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. 11 September 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "f_OCUS in the Counihan Virtual Gallery". moreland.vic.gov.au. Moreland City Council. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "The Burning World". bendigoregion.com.au. Bendigo Art Gallery. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Artists | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Hoda Afshar: Born 1983". maph.org.au. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Works by Hoda Afshar | Art Gallery of NSW". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ Monash University Museum Annual Report 2019. Monash University. 2020. p. 24. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "2018 Acquisitions". murdoch.edu.au. Murdoch University. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ From the Collection: National Anthem & A New World Order. University of Melbourne. 2019. pp. 21, 31, 36, 37. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ New exhibition celebrates Deakin's rich and varied art collection (Media Release), Deakin University, 7 November 2019, retrieved 25 March 2021

- ^ "Remain". artgallery.wa.gov.au. Art Gallery of Western Australia. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

Further reading

- Afshar, Hoda (5 July 2020). "Hoda Afshar". Artist Profile (Interview). Interviewed by Shkembi, Nur.

This interview was originally published in Artist Profile, Issue 45, 2018

- Afshar, Hoda (24 February 2021). "Hoda Afshar and Clarice Beckett" (Audio). ABC Radio National (Interview). The Art Show. Interviewed by Benson, Namila.

Expires: Sat 27 Apr 2024.

Afshar talks about Agonistes.