History of encyclopedias

Encyclopedias have progressed from the beginning of history in written form, through medieval and modern times in print, and most recently, displayed on computer and distributed via computer networks.

Western encyclopedias

Ancient times

Encyclopedias have existed for around 2,000 years, although even older glossaries such as the Babylonian Urra=hubullu and the ancient Chinese Erya are also sometimes described as "encyclopedias".

Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (/ˈmɑːrkəs təˈrɛnʃəs ˈværoʊ/; 116 BC – 27 BC) was an ancient Roman scholar and writer.

His Nine Books of Disciplines became a model for later encyclopedists, especially Pliny the Elder. The most noteworthy portion of the Nine Books of Disciplines is its use of the liberal arts as organizing principles.[1] Varro decided to focus on identifying nine of these arts: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, musical theory, medicine, and architecture. Using Varro's list, subsequent writers defined the seven classical "liberal arts of the medieval schools".[1]

Pliny the Elder

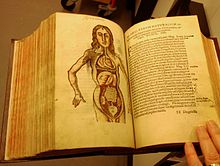

The earliest encyclopedic work to have survived to modern times is the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, a Roman statesman living in the 1st century AD. He compiled a work of 37 chapters covering natural history, architecture, medicine, geography, geology, and all aspects of the world around him. He stated in the preface that he had compiled 20,000 facts from 2000 works by over 200 authors, and added many others from his own experience. The work was published around AD 77–79, although he probably never finished proofing the work before his death in the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79.[2]

My subject is a barren one – the world of nature, or in other words life; and that subject in its least elevated department, and employing either rustic terms or foreign, many barbarian words that actually have to be introduced with an apology. Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one Greek who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject.[2]

He also elaborates on the difficulties of writing such a work:

It is a difficult task to give novelty to what is old, authority to what is new, brilliance to the common-place, light to the obscure, attraction to the stale, credibility to the doubtful, but nature to all things and all her properties to nature.[2]

This work became very popular in Antiquity, and survived, with many copies being made and distributed in the western world. It was one of the first classical manuscripts to be printed in 1470, and has remained popular ever since as a source of information on the Roman world, and especially Roman art, Roman technology and Roman engineering. It is also a recognised source for medicine, art, mineralogy, zoology, botany, geology and many other topics not discussed by other classical authors. Among many interesting entries are those for the elephant and the murex snail, the much sought-after source of Tyrian purple dye.[2]

Although his work has been criticized for the lack of candor in checking the "facts", some of his text has been confirmed by recent research, like the spectacular remains of Roman gold mines in Spain, especially at Las Médulas, which Pliny probably saw in operation while a Procurator there a few years before he compiled the encyclopedia. Although many of the mining methods are now redundant, such as hushing and fire-setting, it is Pliny who recorded them for posterity, thereby helping us understand their importance in a modern context. Pliny makes clear the fact in the preface to his work that he had checked his facts by reading and comparing the works of others, as well as referring to them by name. Many such books are now lost works and remembered only by his references, much like the lost sources mentioned in the work of Vitruvius a century earlier.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

The work De nuptiis Mercurii et Philologiae ("About the wedding of Mercury and Philologia") written by Martianus Capella (4th-5th century) was very influential on the successive medieval encyclopedias. It consists in a complete encyclopedia of classical erudition. It firstly introduced the division and classification of the seven liberal arts (trivium and quadrivium), followed by many successive works along the Middle Ages.

The first Christian encyclopedia was the Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum of Cassiodorus (543–560), which were divided in two parts: the first one dealt with Christian Divinity; the second one described the seven liberal arts.

Saint Isidore of Seville, one of the greatest scholars of the early Middle Ages, is widely recognized as being the author of the first known encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, the Etymologiae or Origines (around 630), in which he compiled a sizable portion of the learning available at his time, both ancient and modern. The encyclopedia has 448 chapters in 20 volumes, and is valuable because of the quotes and fragments of texts by other authors that would have been lost had they not been collected by Saint Isidore.

The most popular encyclopedia of the Carolingian Age was the De universo or De rerum naturis by Rabanus Maurus, written about 830, which was based on the Etymologiae.

Many encyclopedic works were written during the 12th and 13th centuries. Among them was Hortus deliciarum (1167–1185) by Herrad of Landsberg, which is thought to be the first encyclopedia written by a woman. De proprietatibus rerum by Bartholomeus Anglicus (1240) is often described as the most widely read and quoted encyclopedia in the High Middle Ages,[3] while Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Majus (1260) was the most ambitious encyclopedia in the late-medieval period, at over 3 million words.[3]

The first encyclopedias in vernacular languages were translations or abridgements of works in Latin. Among them, the most famous is Li livre dou Trésor, written in French by the Florentine Brunetto Latini. It is mainly based on the Speculum Majus. The works by the Flemish Jacob van Maerlant, as a whole, are regarded as an encyclopedia. These works, too, are based on former Latin texts. In late medieval Europe, several authors had the ambition of compiling the sum of human knowledge in a certain field or overall, for example Bartholomew of England, Vincent of Beauvais, Radulfus Ardens, Sydrac, Brunetto Latini, Giovanni da Sangiminiano, Pierre Bersuire. Some were women, like Hildegard of Bingen and Herrad of Landsberg. The most successful of those publications were the Speculum Maius (Great Mirror) of Vincent of Beauvais and the De proprietatibus rerum (On the Properties of Things) by Bartholomew of England. The latter was translated (or adapted) into French, Provençal, Italian, English, Flemish, Anglo-Norman, Spanish, and German during the Middle Ages. Both were written in the middle of the 13th century. No medieval encyclopedia bore the title Encyclopaedia – they were often called On nature (De natura, De naturis rerum), Mirror (Speculum maius, Speculum universale), Treasure (Trésor).[5] The first encyclopedic work to adopt a single alphabetical order for entries across a variety of topics was the fourteenth-century Omne Bonum, compiled by James le Palmer.

Renaissance

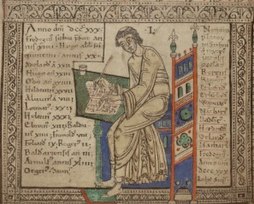

These works were all hand copied and thus rarely available, beyond wealthy patrons or monastic men of learning: they were expensive, and usually written for those extending knowledge rather than those using it.[3]

During the Renaissance, the creation of printing allowed a wider diffusion of encyclopedias and every scholar could have his or her own copy.

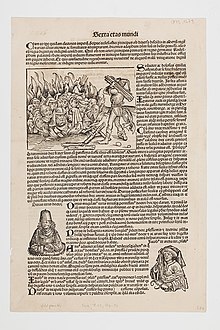

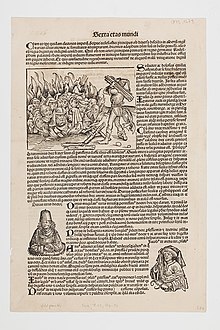

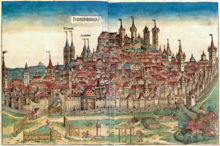

In 1493, the Nuremberg Chronicle was produced, containing hundreds of illustrations, of historical figures, events and geographical places. Written as an encyclopedic chronicle, it remains one of the best-documented early printed books—an incunabulum—and one of the first to successfully integrate illustrations and text. Illustrations depicted many never before illustrated major cities in Europe and the Near East.[6] 645 original woodcuts were used for the illustrations.[7]

The De expetendis et fugiendis rebus by Giorgio Valla was posthumously printed in 1501 by Aldo Manuzio in Venice. This work followed the traditional scheme of liberal arts. However, Valla added the translation of ancient Greek works on mathematics (firstly by Archimedes), newly discovered and translated.

The Margarita Philosophica by Gregor Reisch, printed in 1503, was a complete encyclopedia explaining the seven liberal arts.

Much encyclopaedism of the French Renaissance was based upon the notion of not including every fact known to humans, but only that knowledge that was necessary, where necessity was judged by a wide variety of criteria, leading to works of greatly varying sizes. Béroalde de Verville laid the foundation for his encyclopaedic works in a hexameral poem entitled Les cognoissances nécessaires for example. Often, the criteria had moral bases, such as in the case of Pierre de La Primaudaye's L'Académie française and Guillaume Telin's Bref sommaire des sept vertus &c.. Encyclopaedists encountered several problems with this approach, including how to decide what to omit as unnecessary, how to structure knowledge that resisted structure (often simply as a consequence of the sheer amount of material that deserved inclusion), and how to cope with the influx of newly discovered knowledge and the effects that it had on prior structures.[8]

The term encyclopaedia was coined by 16th-century humanists who misread copies of their texts of Pliny[9] and Quintilian,[10] and combined the two Greek words "enkyklios paedia" into one word, έγκυκλοπαιδεία.[11] The phrase enkyklios paedia (ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία) was used by Plutarch and the Latin word encyclopaedia came from him. The first work titled in this way was the Encyclopedia orbisque doctrinarum, hoc est omnium artium, scientiarum, ipsius philosophiae index ac divisio written by Johannes Aventinus in 1517.[citation needed]

The English physician and philosopher, Sir Thomas Browne used the word 'encyclopaedia' in 1646 in the preface to the reader to define his Pseudodoxia Epidemica, a major work of the 17th-century scientific revolution. Browne structured his encyclopaedia upon the time-honoured scheme of the Renaissance, the so-called 'scale of creation' which ascends through the mineral, vegetable, animal, human, planetary, and cosmological worlds. Pseudodoxia Epidemica was a European best-seller, translated into French, Dutch, and German as well as Latin it went through no fewer than five editions, each revised and augmented, the last edition appearing in 1672.

Financial, commercial, legal, and intellectual factors changed the size of encyclopedias. During the Renaissance, middle classes had more time to read and encyclopedias helped them to learn more. Publishers wanted to increase their output so some countries like Germany started selling books missing alphabetical sections, to publish faster. Also, publishers could not afford all the resources by themselves, so multiple publishers would come together with their resources to create better encyclopedias. When publishing at the same rate became financially impossible, they turned to subscriptions and serial publications. This was risky for publishers because they had to find people who would pay all upfront or make payments. When this worked, capital would rise and there would be a steady income for encyclopedias. Later, rivalry grew, causing copyright to occur due to weak underdeveloped laws. Some publishers would copy another publisher's work to produce an encyclopedia faster and cheaper so consumers did not have to pay as much and thus could sell more. Encyclopedias made it to where middle-class citizens could basically have a small library in their own house. Europeans were becoming more curious about their society around them causing them to revolt against their government.[12]

Traditional encyclopedias

Rise of printed encyclopedias

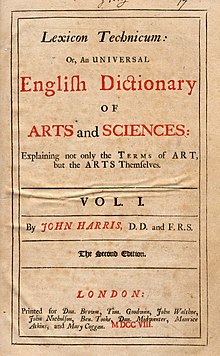

The beginnings of the modern idea of the general-purpose, widely distributed printed encyclopedia precede the 18th century encyclopedists. However, Chambers' Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1728), and the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D'Alembert (1751 onwards), as well as Encyclopædia Britannica and the Conversations-Lexikon, were the first to realize the form we would recognize today, with a comprehensive scope of topics, discussed in depth and organized in an accessible, systematic method. Chambers, in 1728, followed the earlier lead of John Harris's Lexicon Technicum of 1704 and later editions (see also below); this work was by its title and content "A Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves".

John Harris is often credited with introducing the now-familiar alphabetic format in 1704 with his English Lexicon Technicum: Or, A Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves – to give its full title. Organized alphabetically, its content does indeed contain explanation not merely of the terms used in the arts and sciences, but of the arts and sciences themselves. Sir Isaac Newton contributed his only published work on chemistry to the second volume of 1710. Its emphasis was on science—and conformably to the broad 18th-century understanding of the term 'science', its content extends beyond what would be called science or technology today, and includes topics from the humanities and fine arts, e.g. a substantial number from law, commerce, music, and heraldry. At about 1,200 pages, its scope can be considered as more that of an encyclopedic dictionary than a true encyclopedia. Harris himself considered it a dictionary; the work is one of the first technical dictionaries in any language.[citation needed]

Ephraim Chambers published his Cyclopædia in 1728. It included a broad scope of subjects, used an alphabetic arrangement, relied on many different contributors and included the innovation of cross-referencing other sections within articles. Chambers has been referred to as the father of the modern encyclopedia for this two-volume work.

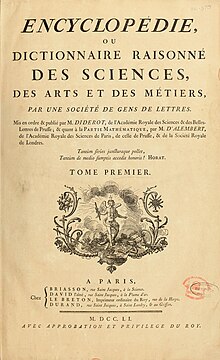

Encyclopédie and Diderot’s perfect encyclopaedia

A French translation of Chambers' work inspired the Encyclopédie, perhaps the most famous early encyclopedia, notable for its scope, the quality of some contributions, and its political and cultural impact in the years leading up to the French Revolution. The Encyclopédie was edited by Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot and published in 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765, and 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772. Five volumes of supplementary material and a two volume index, supervised by other editors, were issued from 1776 to 1780 by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke.

The Encyclopédie represented the essence of the French Enlightenment.[13] The prospectus stated an ambitious goal:

the Encyclopédie was to be a systematic analysis of the "order and interrelations of human knowledge."[14]

Diderot, in his Encyclopédie article of the same name, went further:

"to collect all the knowledge that now lies scattered over the face of the earth, to make known its general structure to the men among we live, and to transmit it to those who will come after us", to make men not only wiser but also "more virtuous and more happy."[15]

Realizing the inherent problems with the model of knowledge he had created, Diderot's view of his own success in writing the Encyclopédie were far from ecstatic. Diderot envisioned the perfect encyclopedia as more than the sum of its parts. In his own article on the encyclopedia, Diderot also wrote, "Were an analytical dictionary of the sciences and arts nothing more than a methodical combination of their elements, I would still ask whom it behooves to fabricate good elements." Diderot viewed the ideal encyclopedia as an index of connections. He realized that all knowledge could never be amassed in just one large work, but he hoped the relations among the subjects could be.

The Encyclopédie in turn inspired the venerable Encyclopædia Britannica, which had a modest beginning in Scotland: the first edition, issued between 1768 and 1771, had just three hastily completed volumes – A–B, C–L, and M–Z – with a total of 2,391 pages. By 1797, when the third edition was completed, it had been expanded to 18 volumes addressing a full range of topics, with articles contributed by a range of authorities on their subjects.

The German-language Conversations-Lexikon was published at Leipzig from 1796 to 1808, in 6 volumes. Paralleling other 18th century encyclopedias, its scope was expanded beyond that of earlier publications, in an effort at comprehensiveness. It was, however, intended not for scholarly use but to provide results of research and discovery in a simple and popular form without extensive detail. This format, a contrast to the Encyclopædia Britannica, was widely imitated by later 19th century encyclopedias in Britain, the United States, France, Spain, Italy and other countries. Of the influential late-18th century and early-19th century encyclopedias, the Conversations-Lexikon is perhaps most similar in form to today's encyclopedias.

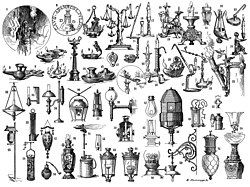

The early years of the 19th century saw a flowering of encyclopedia publishing in the United Kingdom, Europe and America. In England Rees's Cyclopædia (1802–19) contains an enormous amount in information about the industrial and scientific revolutions of the time. A feature of these publications is the high-quality illustrations made by engravers like Wilson Lowry of art work supplied by specialist draftsmen like John Farey, Jr. Encyclopedias were published in Scotland, as a result of the Scottish Enlightenment, for education there was of a higher standard than in the rest of the United Kingdom. The National Revival of Bulgaria, influenced by the Enlightenment, resulted in Petar Beron's Primer with Various Instructions (also known as the Fish Primer) in 1824. It was a small encyclopedia for children, containing fables, proverbs, ancient history, basic arithmetics, zoology and linguistics.[16] Beron later published a 7-volume work in natural sciences known as Panepisteme in 1867.

The 17-volume Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle and its supplements were published in France by Pierre Larousse from 1866 to 1890.

Encyclopædia Britannica appeared in various editions throughout the century, and the growth of popular education and the Mechanics' Institutes, spearheaded by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge led to the production of the Penny Cyclopaedia, as its title suggests issued in weekly numbers at a penny each like a newspaper. A more commercially successful encyclopaedia then Penny Cyclopaedia aimed at the same audiences was Chambers's Encyclopaedia A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People, edited by Andrew Findlanter. It was partly based on a translation into English of the 10th edition of the German-language Konversations-Lexikon, which would become the Brockhaus Enzyklopädie.

The publishers found it necessary, however, to supplement the core text with a significant amount of additional material, including more than 4000 illustrations not present in Brockhaus. Andrew Findlater was the acting editor and spent ten years on the project.1

Chambers's Encyclopaedia first appeared between 1859 and 1868 in 520 weekly parts at three-halfpence each[14] and totalled ten octavo volumes, with 8,320 pages, and over 27,000 articles from over 100 authors. It was also published as bound volumes between 1860 and 1868.

In the early 20th century, the Encyclopædia Britannica reached its eleventh edition, and inexpensive encyclopedias such as Harmsworth's Universal Encyclopaedia and Everyman's Encyclopaedia were common.

Popular and affordable encyclopedias such as Harmsworth's Universal Encyclopaedia and The Children's Encyclopædia appeared in the early 1920s.

In the United States, the 1950s and 1960s saw the introduction of several large popular encyclopedias, often sold on installment plans. The best known of these were World Book and Funk and Wagnalls. As many as 90% were sold door to door. Jack Lynch says in his book You Could Look It Up that encyclopedia salespeople were so common that they became the butt of jokes. He describes their sales pitch saying, "They were selling not books but a lifestyle, a future, a promise of social mobility." A 1961 World Book ad said, "You are holding your family’s future in your hands right now," while showing a feminine hand holding an order form.[17]

The second half of the 20th century also saw the publication of several encyclopedias that were notable for synthesizing important topics in specific fields, often by means of new works authored by significant researchers. Such encyclopedias included The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (first published in 1967 and now in its second edition), and Elsevier's Handbooks In Economics[18] series. This trend has continued into the 21st century, producing encyclopedias of at least one volume in size for most if not all academic disciplines, including, typically, such narrow topics such as bioethics and African-American history.

International development

During the 19th and early 20th century, many smaller or less developed languages saw their first encyclopedias, using French, German, and English role models. While encyclopedias in larger languages, having large markets that could support a large editorial staff, churned out new 20-volume works in a few years and new editions with brief intervals, such publication plans often spanned a decade or more in non-European languages.

The first large encyclopedia in Russian, Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (86 volumes, 1890–1906), was a direct cooperation with the German Brockhaus.

Without such a formal cooperation, the Swedish Conversations-lexicon (4 volumes, 1821–1826) was a translation of Brockhaus 2nd edition. The first encyclopedia written originally in Swedish was Svenskt konversationslexikon (4 volumes, 1845–1851) by Per Gustaf Berg. A more ambitious project was Nordisk familjebok, established in 1875 and intended to comprise 6 volumes. But in 1885, when it had published 8 volumes and gotten only halfways (A–K), the publisher turned to the government for extra funding; encyclopedias had become national monuments. It was finished in 1894 with 18 volumes,[19] with two supplement volumes (1896–1899).

The first major Danish encyclopedia was Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon (19 volumes, 1893–1911).

In Norway, encyclopedias follow the unique history of the Norwegian language, the Bokmål variant having branched off from Danish during the 19th century. After the national independence in 1905, publisher Aschehoug (owned by William Martin Nygaard) hired librarian Haakon Nyhuus to edit Illustreret norsk konversationsleksikon (6 volumes, 1907–1913), in later editions known as Aschehougs konversasjonsleksikon. In the Nynorsk variant of the language, Norsk Allkunnebok (10 volumes, 1948–1966) was the only encyclopedia until the arrival of Wikipedia.

The first major Finnish encyclopedia was Tietosanakirja (11 volumes, 1909–1922). Inspired by the minority language example of Norsk Allkunnebok, a Swedish-language encyclopedia of Finland was initiated in 1969 and eventually published as Uppslagsverket Finland (3 volumes, 1982–1985; 2nd edition in 5 volumes, 2003–2007). With such a small market, the sales revenue only covered the printing cost, while editors were paid by endowments. In 2009 the entire contents was made available online, free of charge.

Already during czarist Russian rule, two editions appeared of the Latvian Konversācijas vārdnīca (2 volumes, 1891–1893; 4 volumes, 1906–1921). The larger Latviešu konversācijas vārdnīca (21 volumes, A–Tjepolo, 1927–1940) was interrupted by World War II and never completed. After the war, Latvian emigrants in Sweden published Latvju enciklopēdija (3 volumes, 1950–1956, with a supplement volume in 1962). Soviet authorise published Latvijas PSR mazās enciklopēdijas (3 volumes, 1967–1970) and Latvijas padomju enciklopēdija (10 volumes, 1981–1988).[20]

Similarly, in the history of Lithuanian encyclopedias, the Lietuviškoji enciklopedija (9 volumes A–J, 1933–1941) was interrupted by World War II and never completed. Lithuanian emigrants in the United States published Lietuvių enciklopedija (35 volumes, 1953–1966). Soviet authorities published Mažoji lietuviškoji tarybinė enciklopedija (3 volumes, 1966–1971), Lietuviškoji tarybinė enciklopedija (12 volumes, 1976–1985), and Tarybų Lietuvos enciklopedija (4 volumes, 1985–1988). First Turkish encyclopedia was Kamus-ül-Ulûm ve’l-Maarif written by Ali Suvai in 1870 after that Ahmet Rifat Efendi's 7 volumes work "Lûgaat-i Tarihiye ve Coğrafiye" (Dictionary of History and Geography) published in Istanbul at 1881.[21]

Emergence of digital and online encyclopedia

Digital technologies and online crowdsourcing allowed encyclopedias to break away from traditional limitations in both breadth and depth of topics covered.

Digital encyclopedias

By the late 20th century, encyclopedias were being published on CD-ROMs for use with personal computers. Microsoft's Encarta, launched in 1993, was a landmark example as it had no printed equivalent. Articles were supplemented with video and audio files as well as numerous high-quality images. After sixteen years, Microsoft discontinued the Encarta line of products in 2009.[22]

Traditional encyclopedias are written by a number of employed text writers, usually people with an academic degree, and distributed as proprietary content.

Encyclopedias are essentially derivative from what has gone before, and particularly in the 19th century, copyright infringement was common among encyclopedia editors. However, modern encyclopedias are not merely larger compendia, including all that came before them. To make space for modern topics, valuable material of historic use regularly had to be discarded, at least before the advent of digital encyclopedias. Moreover, the opinions and world views of a particular generation can be observed in the encyclopedic writing of the time. For these reasons, old encyclopedias are a useful source of historical information, especially for a record of changes in science and technology.[23]

As of 2007, old encyclopedias whose copyright has expired, such as the 1911 edition of Britannica, are also the only free content English encyclopedias released in print form. However, works such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, which were created in the public domain,[citation needed] exist as free content encyclopedias in other languages.

Rise of online, free, crowd-sourced encyclopedias

The concept of a new free encyclopedia began with the Interpedia proposal on Usenet in 1993, which outlined an Internet-based online encyclopedia to which anyone could submit content and that would be freely accessible. Early projects in this vein included Everything2 and Open Site. In 1999, Richard Stallman proposed the GNUPedia, an online encyclopedia which, similar to the GNU operating system, would be a "generic" resource. The concept was very similar to Interpedia, but more in line with Stallman's GNU philosophy.[citation needed]

It was not until Nupedia and later Wikipedia that a stable free encyclopedia project was able to be established on the Internet.[citation needed]

The English Wikipedia, which was started in 2001, became the world's largest encyclopedia in 2004 at the 300,000 article stage.[24] By late 2005, Wikipedia had produced over two million articles in more than 80 languages with content licensed under the copyleft GNU Free Documentation License. As of August 2009, Wikipedia had over 3 million articles in English and well over 10 million combined in over 250 languages. Wikipedia currently has 6,930,549 articles in English. Since 2003, other free encyclopedias like the Chinese-language Baidu Baike and Hudong, as well as English language encyclopedias like Citizendium and Knol have appeared. Knol has been discontinued.[citation needed]

An encyclopedia's hierarchical structure and evolving nature is particularly adaptable to a digital format, and all major printed general encyclopedias had moved to this method of delivery by the end of the 20th century. Disk-based, typically DVD-ROM or CD-ROM format, publications have the advantage of being cheaply produced and easily portable. Additionally, they can include media which are impossible to store in the printed format, such as animations, audio and video. Hyperlinking between conceptually related items is also a significant benefit, although even Diderot's encyclopedia had cross-referencing.[citation needed]

On-line encyclopedias offer the additional advantage of being dynamic: new information can be presented almost immediately, rather than waiting for the next release of a static format, as with a disk- or paper-based publication. Many printed encyclopedias traditionally published annual supplemental volumes ("yearbooks") to update events between editions, as a partial solution to the problem of staying up-to-date, but this of course required the reader to check both the main volumes and the supplemental volumes. Some disk-based encyclopedias offer subscription-based access to online updates, which are then integrated with the content already on the user's hard disk in a manner not possible with a printed encyclopedia.[citation needed]

Information in a printed encyclopedia necessarily needs some form of hierarchical structure. Traditionally, the method employed is to present the information ordered alphabetically by the article title. However, with the advent of dynamic electronic formats the need to impose a pre-determined structure is less necessary. Nonetheless, most electronic encyclopedias still offer a range of organizational strategies for the articles, such as by subject, area, or alphabetically.[citation needed]

Digital encyclopedias also offer greater search abilities than printed versions. While the printed versions rely on indexes to assist in searching for topics, computer accessible versions allow searching through article text for keywords or phrases.[citation needed]

Specialized encyclopedias may offer a more comprehensive content. For example, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ADAM Medical Encyclopedia (which includes over 4,000 articles about diseases, tests, symptoms, injuries, and surgeries), the Wiki Encyclopedia of Law and the Encyclopedia of Earth all provide a more focused list of topics.[citation needed]

Eastern encyclopedias

Byzantine encyclopedias

Byzantine encyclopedias were compendia of information about both Ancient and Byzantine Greece. The first of them was the Bibliotheca written by the patriarch Photius (9th century).

The Suda or Souda (Greek: Σοῦδα) is a massive 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Suidas. It is an encyclopedic lexicon, written in Greek, with 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often derived from medieval Christian compilers.

Arabic and Persian

The early Muslim compilations of knowledge in the Middle Ages included many comprehensive works.

The encyclopedia of Suda, a massive 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia, had 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often derived from medieval Christian compilers. The text was arranged alphabetically with some slight deviations from common vowel order and place in the Greek alphabet.

Around year 960, the Brethren of Purity of Basra were engaged in their Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity.[25]

Additional notable works include Abu Bakr al-Razi's encyclopedia of science, the Mutazilite Al-Kindi's prolific output of 270 books, and Ibn Sina's medical encyclopedia, which was a standard reference work for centuries. Also notable are works of universal history (or sociology) from Asharites, al-Tabri, al-Masudi, Tabari's History of the Prophets and Kings, Ibn Rustah, al-Athir, and Ibn Khaldun, whose Muqadimmah contains cautions regarding trust in written records that remain wholly applicable today.[citation needed] These scholars have influenced methods of research and editing, due in part to the Islamic practice of isnad which emphasized fidelity to written record, checking sources, and skeptical inquiry.[citation needed] An acquisition of knowledge it was believed not only enlightened the mind but also led to a greater appreciation of God. To be remarkable during these times was to keep pace with the ‘march of intellect’ and the printing press became a necessity for the widespread dissemination of this commodity called knowledge. As a means of cultural production, the printing press was the very embodiment of the ideal of ‘Enlightenment’.[26]

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, recent works include the Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam prepared in 10 volumes by The Encyclopaedia Islamica Foundation,[27] the Encyclopaedia of Contemporary Islam published as a four-volume English encyclopedia including around 1200 entries. Other such works are: the Encyclopedia of Imam Ali, the Encyclopedia of Qur'anology, and the Encyclopedia of Lady Fātima, all published by the Islamic Research Institute for Culture and Thought (IICT).[28]

India

The Siribhoovalaya

The Siribhoovalaya (Kannada: ಸಿರಿಭೂವಲಯ), dated between 800 AD to 15th century, is a work of kannada literature written by Kumudendu Muni, a Jain monk. It is unique because rather than employing alphabets, it is composed entirely in Kannada numerals. Many philosophies which existed in the Jain classics are eloquently and skillfully interpreted in the work.

The work also contains valuable information about various sciences including mathematics, chemistry, physics, astronomy, medicine, history, space travel, etc. Karlamangalam Srikantaiah, the editor of the first edition, has claimed that the work contains instructions for travel in water and space travel. It is also said that the work contains information about the production of modern weapons.[29]

The work is said to have around 600,000 verses, nearly six times as big as the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata. Totally there are 26 chapters constituting it a big volume of which only three have been decoded.

Varāhamihira

Varāhamihira's (505–587 AD) Brihat Samhita ("large compilation") is an encyclopedic work, not only dealing with astrology but also rainfall, clouds, water-divination, intentions and characteristics of animals, perfumes, erotic recipes, pimples, temples, architecture and other topics.[30]

China

The enormous encyclopedic work in China of the Four Great Books of Song, compiled by the 11th century during the early Song dynasty (960–1279), was a massive literary undertaking for the time. The last encyclopedia of the four, the Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau, amounted to 9.4 million Chinese characters in 1000 written volumes.

The period of the encyclopedists spanned from the tenth to seventeenth centuries, during which the government of China employed hundreds of scholars to assemble massive encyclopedias.[31] The largest of which is the Yongle Encyclopedia; its compilation was overseen by the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty, and was completed in 1408. It consisted of almost 23,000 folio volumes in manuscript form,[31] the largest encyclopedia in history, until surpassed by Wikipedia in 2007.

In the succeeding Qing dynasty, the Qianlong Emperor personally composed 40,000 poems as part of a 4.7 million page library in 4 divisions, including thousands of essays, called the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries which is probably the largest collection of books in the world. It is instructive to compare his title for this knowledge, Watching the waves in a Sacred Sea to a Western-style title for all knowledge. Encyclopedic works, both in imitation of Chinese encyclopedias and as independent works of their own origin, have been known to exist in Japan since the 9th century.[citation needed]

There were many great encyclopedists throughout Chinese history, including the scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) with his Dream Pool Essays of 1088, the statesman, inventor, and agronomist Wang Zhen (active 1290–1333) with his Nong Shu of 1313, and the written Tiangong Kaiwu of Song Yingxing (1587–1666), the latter of whom was termed the "Diderot of China" by British historian Joseph Needham.[32]

See also

References

- ^ a b Lindberg, David (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d Naturalis Historia

- ^ a b c See "Encyclopedia" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages.

- ^ "Liber Floridus [manuscript]". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Monique Paulmier-Foucart, "Medieval Encyclopaedias", in André Vauchez (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, James Clarke & Co, 2002.

- ^ Hennessy, Kathryn (2018). Remarkable Books, The World's Most Beautiful and Historic Works. New York: DK Penguin Random House. p. 78. ISBN 9781465483065.

- ^ McPhee, John; Museums and Galleries NSW (2008). Great Collections: treasures from Art Gallery of NSW, Australian Museum, Botanic Gardens Trust, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, Museum of Contemporary Art, Powerhouse Museum, State Library of NSW, State Records NSW. Museums & Galleries NSW. p. 37. ISBN 9780646496030. OCLC 302147838.

- ^ Neil Kenny (1991). The Palace of Secrets: Beroalde de Verville and Renaissance Conceptions of Knowledge. Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-19-815862-9.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Preface 14.

- ^ Quintilian, Institutio oratoria, 1.10.1: ut efficiatur orbis ille doctrinae, quem Graeci ἐγκύκλιον παιδείαν vocant.

- ^ έγκυκλοπαιδεία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, at Perseus Project: "f. l. [= falsa lectio, Latin for "false reading"] for ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία"

- ^ Loveland, J. (2012). "Why Encyclopedias Got Bigger … and Smaller". Information & Culture. 47 (2): 233–254. doi:10.1353/lac.2012.0012. S2CID 144466580.

- ^ Himmelfarb, Gertrude (2004). The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4236-4.

- ^ Jean le Rond d'Alembert, "Preliminary Discourse", in Denis Diderot's The Encyclopédie: Selections, ed. and trans. Stephen J. Gendzier (1967), cited in Hillmelfarb 2004

- ^ Denis Diderot, Rameau's Nephew and Other Works, trans. and ed. Jacques Barzun and Ralph H. Bowen (1956), cited in Himmelfarb 2004

- ^ Todorov, Nikolai (1968). Bulgaria: historical and geographical outline. Sofia. p. 263.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Onion, Rebecca (June 3, 2016). "How Two Artists Turn Old Encyclopedias Into Beautiful, Melancholy Art". Slate. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ "Economics and Finance – Elsevier". Elsevier.com. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Slutord, postscriptum to the 1st edition, 1894.

- ^ List of Latvian encyclopedias Archived 2012-12-22 at the Wayback Machine from the website Historia.lv.

- ^ "Ansiklopedi (encyclopedia) (tr)". Yeniansiklopedi.com. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ Important Notice: MSN Encarta to be Discontinued. MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-27.

- ^ Kobasa, Paul A. "Encyclopedia." World Book Online Reference Center. 2008. [Place of access.] 13 Jan. 2008 <http://www.worldbookonline.com/wb/Login?ed=wb&tu=%2Fwb%2FArticle%3Fid%3Dar180800>

- ^ "Wikipedia Passes 300,000 Articles making it the worlds largest encyclopedia", Linux Reviews, 2004 Julich y 7.

- ^ P.D. Wightman (1953), The Growth of Scientific Ideas

- ^ Nair, Savithri Preetha. "'...Of real use to the people': The Tanjore printing press and the spread of useful knowledge." Sage Publications.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Islamica Foundation. بنیاد دائره المعارف اسلامی". Encyclopaediaislamica.com. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ "پژوهشكده دانشنامه نگاري – پژوهشکده دانشنامه نگاری دینی". Ency.iict.ac.ir. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ "Pustak Shakti Product 2". 2012-02-06. Archived from the original on 2012-02-06. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ M. Ramakrishna Bhat. Varahamihira's Brihat Samhita. Motilal Banarsidass.

- ^ a b Murray, Stuart (2009). The library: an illustrated history. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 9781602397064. OCLC 277203534.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 102.

Further reading

- Garfield, Simon (2022). All the Knowledge in the World: The Extraordinary History of the Encyclopaedia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-4746-1077-3.

External links

- Encyclopedia – Diderot's article on the Encyclopedia from the original Encyclopédie

- De expetendis et fugiendis rebus – First Renaissance encyclopedia

- Digital encyclopedias put the world at your fingertips – CNET article

- Chambers' Cyclopaedia, 1728, with the 1753 supplement