History of dolphin fishing and utilization in Japan

This article describes the history of dolphin fishing and utilization in Japan. Dolphins capturing are sometimes referred to as hunting and sometimes as fishing. In Japan, the word fishing (漁) has traditionally been used instead of hunting (猟) for dolphin capturing, so this article will use the word "fishing" for convenience. The catch of dolphins is not stable every year; sometimes they are caught in large quantities, and sometimes they are rarely caught. Also, when a large school of dolphins arrives, a large number of workers are temporarily needed. As a result, dolphin fishing profits were often allocated and taxed as contingent. In many cases, there was also a rule that those with dolphin fishing rights could call in personnel when fishing for dolphins.

Dolphin fishing has been conducted irregularly, and in many cases, there are no records of its implementation. Therefore, the following examples are only those that can be confirmed in the literature and do not describe the entire history of dolphin fishing in Japan.

Ancient times

Dolphin fishing began at the Okinoshima site (now Tateyama) about 10,000 years ago in the early Jōmon period,[1]: 217 and large numbers of dolphin bones have been excavated from the Tanimukai shell mound (Minamibōsō) and Inahara shell mound (Tateyama). Dolphin bones with obsidian punctures have also been found in Inahara shell mound.[1]: 22 In addition, dolphin bones have been found in Nego shell mound (Kamagaya), Kosaku shell mound (Funabashi), Hatagiri Cave site (Tateyama,)[2]: 96 and Hamazume site (Kyōtango.)[3]

Older traces of dolphin fishing have been found at the Mawaki Site (Noto), which flourished from about 6,000 to about 2,000 years ago.[4]

Dolphin bones have also been found at Irie shell mound (Tōyako),[5] Inariyama shell mound (Yokohama),[6] Shomyoji shell mound (Yokohama),[7] Idogawa site.[8]

Although it is uncertain whether it actually exists or not, there is a tradition that Emperor Ōjin, who is said to have been an emperor around the 5th century, was presented with a dolphin as a reward from the gods when he was a crown prince.[9]

Written in 733, Izumo Fudoki (出雲国風土記) contains a description of dolphin meat.[10] However, this is the only reference that states that dolphins were eaten during this period.[11]

Middle ages

The earliest known record of the systematic capture of dolphins in Japan is a descendant left in 1377 by Aokata Shigeshi of the Aokata clan, a powerful family on the Gotō Islands, which suggests that a "dolphin net fishing" (Yuruka-ami) already existed at that time.[12]

青方重置文案

かつをあミ、しひあみ、ゆるかあみ、ちからあらハせうせうハ人をもかり候いて、しいたしてちきょうすへし、

ゑいわ三年三月十七日

— 『青方文書』

Nakamura Yoichiro, a professor at Shizuoka Sangyo University, interpreted this as follows: "In a letter left by Aokata Shigeshi to his descendants, he wrote that nets targeting bonito, tunas, and dolphines should be managed and operated with great effort, even if it means mobilizing human labor," and inferred the existence of a dolphin fishing by setting up tatekiri nets.[13] A tatekiri net is a net used to partition the area from the seafloor to the sea surface.[14] The tatekiri nets are not used exclusively for dolphin fishing, but are a tool used to catch tuna and other fish.[15]

Even in medieval Tsushima Island, there are documents that suggest that a large number of people were needed to dolphin fishing. A document written in 1404 contains the local lord's instructions for dolphin fishing.[16] Fishing in this period was often done by catching one by one with a harpoon or by using a net to drive in those that happened to stray into the bay.[15]

Documents such as Yamanouchiryourisho and Shijouryuhouchodo, which were probably written in the 15th century, mention dolphin dishes as banquet food. The document Teikinorai, written around the same time, also contains a description of dried dolphin meat.[10]

In January 1557, a nobleman, Yamashina Tokitsugu visited Imagawa Yoshimoto in Suruga Province and was presented with dolphin meat.[17][18] The dolphin meat was presented along with burdock root, and it has been suggested that the meat may have been boiled in miso, as it is today.[19]

Around 1563, the Katsurayama clan, who lived in Katsurayama (present-day Shizuoka Prefecture), gave written instructions that if dolphins came to the cove, gather people to capture them. And they sent officers to take the tax against fishing.[20]

In 1580, a proclamation was issued in Tsushima Island, stipulating that local residents could be temporarily used as workers when dolphins arrived.[21]

Edo period (1603 - 1867)

Taiji (now in Wakayama Prefecture) is said to be the birthplace of old-style whaling and has a whaling history of about 400 years. In this area, not only whales but also dolphins were eaten. In the Edo period, there was gondoh whale fishing mainly offshore with a poking stick. Also, pilot whales that happened to stray into a harbor or other location was sometimes captured by driving it into the water.[22]

In 1625, a decree was issued in Tsushima, giving priority to dolphin fishing even if it meant interfering with the harvesting of kelp.[23]

The ryorimonogatari, written in 1635, describes how to make dolphins meat into sashimi, soup, and stew with vinegar.[10]

Records from 1673 show that of the sales of dolphins caught in Tsushima, one-third was allocated to the local community and two-thirds to the regional government.[24]

In 1675, in Karakuwa, now Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture, there is a record that when a herds of dolphins came in, takikiri nets were set up between the Karakuwa Peninsula and Oshima Island to drive the dolphins in. In Karakuwa, drive fishing was practiced until the beginning of the Meiji era.[25][26]

In 1683, a family in Tsushima had its privileges regarding tax rates on dolphin fishing abolished because of a dispute. This was seen as a move to strengthen the Tsushima local government's control.[27]

The Honcho-Shokukan (本朝食鑑), written in 1692, describes dolphin meat as effective for hemorrhoids and rectal prolapse, although it is almost equal to whale meat.[28]

There was a dispute over fishing rights in Ofunato Bay (present Iwate Prefecture) in 1699, and 32 times were recorded until 1867. These records indicate that nets for sardine fishing were used for dolphin fishing in the region.[29]

In 1716, a group wanted to enter the dolphin fishery in Ohura (now Yamada, Iwate) instead of paying a hefty trade tax to the local government. So the local residents, who have had fishing rights for more than a decade, filed a petition to stop it. It is believed that dolphin fishing began in this village at the initiative of an engineer from what is now Wakayama Prefecture.[30] In response, the local government made a decision to recognize the fishing rights of the local fishing village from the perspective of maintaining the fishing village.[31]

In 1718, it was recorded that 415 dolphins were captured over a period of six days at Yotsugaura in Tsushima Island.[32]

The 1724 pictorial map Yosano Dai Ezu (与謝之大絵図) describes "catching dolphins on the shallow beach" in Hirata village in Tango Province.[3]

In 1745, a dispute related to the large-scale capture of dolphins is recorded in the Yukawa village of in present-day Shizuoka Prefecture.[33]

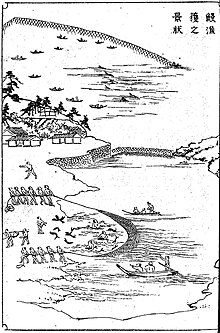

In March 1773, one of the "Hizen Province Product Drawings (肥前国産物図考)", "Dolphin and tuna fishing figure, and Snapper fishing and sea Matters (海豚漁事・鮪網之図・鯛網・海士)" was written by Kizaki Yuken, a samurai of the Karatsu domain.[34] Of these, "Dolphin fissing" depicts the driving fishing to capture a herd of dolphines.[35] The dolphins caught were used for food as well as for liting oil.[36]

According to "Toyu-ki" written by Hezutu Tohsaku in 1786, Ainu people living in Esashi, Hokkaido did not catch whales, but they did catch dolphins, extracted their oil, and used them for food.[37]

The June 1792 account of Ezo, Ezo no Teburi, describes an Ainu fisherman attempting to harvest dolphins.[38]

In 1834, a large Ema (votive tablet) showing dolphin fishing was delivered to Isozaki Shrine (in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture). The picture depicts how dolphins were driven in with nets used for sardine fishing and captured by holding them by hand or poking them with a harpoon.[39]

In 1838, "Noto province fishery pictorial book (能登国採魚図絵)" written by Kitamura Kokujitu, there is a record of dolphin fishing in the village of Manawaki (now Ishikawa Prefecture). According to the report, from March to April of the lunar calendar, about 3 or 4 boats with 6 or 7 crews go out to the sea 3 Li (ca. 5.6 km) offshore as "fish watching boats." When they find a herds of dolphines, they surround it with a coarse net and send a signal to land, and 6 or 7 boats with 3 or 4 crews come to support them. These boats make noise by banging on the edges of the boats, etc., and drive the herds into the bay to be caught. At the most, about 1,000 dolphins were driven in, and it sometimes took two days to catch them all.[40]

In 1858, the catch in Ohura (now Yamada, Iwate) was recorded as 2,200 harbor porpoise and 3,590 common dolphins. They were sold for a total of 800 ryō, with 150 ryō going to taxes, the remaining 60% to the village, and 40% to the investors.[41]

According to "Ito's history" written by Takeo Hamano at the middle of the 19th century, there were few organized fishing groups in Shizuoka at that time, and only Yugawa Village, Matsubara Village (now Itō City) and Inatori Village (now Higashiizu Town) were involved in the practice.[42]

Meiji era (1868 - 1912)

In 1868, Japan underwent a major change of government, known as the Meiji Restoration, and became a centralisation nation. 1875, the Japanese government declared that all fishing rights along the coast of Japan were owned by the Japanese government. The Japanese government leased fishing rights to fishermen through a bidding process, but after some confusion, including capitalists buying up fishing rights, the government decided to recognize traditional fishing rights for villages in 1877.[43] However, dolphin fishing was not specified in these programs because of the limited area in which it was conducted.[43]

Dolphin fishing was abolished in many places after the Meiji Era. For example, in Shizuoka's Yugawa and Matsubara, the fishery was abolished. In Inatori, there is a testimony that the fishery was abolished in the early year of Meiji Era because the arrival of dolphins was unstable and it was unprofitable to fish once or twice a year.[44] However, in Inatori, every time dolphins come to the area, the drive fishing has been revived.[45]

In Kesennuma, Karakuwa in Miyagi Prefecture and Yamada in Iwate Prefecture, schools of dolphins stopped congregating after the early year of the Meiji Era and no more drive fishing was conducted[46]

In the Meiji Era, dolphin fishing began in Kawana, Futo (now Itō City), Tago (now Nishiizu Town), and other areas in Shizuoka Prefecture.[44] Dolphin fishing began in Kawana in 1888, and in 1922, an ema (votive tablet) of dolphin fishing was dedicated to a local shrine.[47] In Futo, the fishery started about 10 years after Kawana, but due to a dispute with Kawana in 1903, not much pursuit fishing was done until after the World War II.[48]

In 1889, a request was made to the Iwate Prefecture local government for a survey of dolphin fishing. According to the survey, the common dolphin and pilot whale were used for food, while the harbor porpoises were used for oil extraction. The number of dolphins caught varied greatly from year to year, sometimes as many as 3,000 were caught in a single fishing trip, and sometimes less than 100.[49]

In 1899, a lookout spotted a herd of 61 pilot whale.[50] A 1906 report to the government explained that the origins of the drive fishing were unknown and that the proceeds of the fishing, which was a communal activity of the village, became the common property of the village.[51]

In 1901, there is a record of profit distribution when 900 dolphins were captured in Tsushima. The profit at that time was basically distributed to the main household, called Honke, and not to the sub-household, called Bunke. Sales at this time amounted to 1,474 yen, and expenses were 550 yen. 524 yen in profit was distributed among 195 honke, which amounted to 4.6 yen per honke. In 1895, however, distribution was made on a different basis.[52]

In 1902, the Fisheries Law was passed in Japan, and in 1903, detailed regul.ations were established. Here, the position of dolphin drive fishing was clearly stated. In response, the residents of Oura in Iwate Prefecture applied for a license to fish for dolphins. The application required, among other things, the provision of documents showing past performance.[53]

A record from 1908 describes the method of dolphin drive fishing. According to the report, 50 to 60 fishing boats surrounded the school in a half-moon shape and drove them into the bay by throwing stones, hitting the surface of the water, and striking the edges of the boats. The bay was then blocked with a tatekiri net. In addition to tailing, a harpoon method called tsukitori was used to catch the fish as they breathed.[54] In those days, meat was used for food, fat for oil, and leather for goods (especially shoes.) As a food, it was commonly boiled in miso with gobo (Arctium lappa), etc.[54]。In Shizuoka Prefecture, they were grilled and eaten after being pickled in soy sauce or mirin and dried in the sun. Oil was extracted from the peel and used to make fried oil and soap. The squeezed peel was deep-fried and eaten as a snack. The rest was used as a good fertilizer.[55]

In Nago City, Okinawa Prefecture, dolphins (small cetaceans) are called pitu or heatu, and although the origin of the fishery is unknown,[56] they were fished as late as the early Meiji period and were an important source of protein. The method is fishing using traditional Okinawa boats, Sabani.[56] According to the Japan Fisheries Agency's classification, the type of fishing is considered to be poking with a stick, and in recent years, most of the fish are caught by hand-thrown harpoons.[57][56] The main targets are short-finned pilot whale and common bottlenose dolphin, which migrate to Nago Bay from February to June every year.[58]

Taishō to end of World War II (1912 - 1945)

In Shizuoka Prefecture, from the beginning of the Taishō era to the early Showa period, it declined temporarily due to a decrease in dolphin migration.[59]

In the 1920s, the last large-scale dolphin fishery took place in Ofunato Bay, Iwate Prefecture. By that time, the custom of eating dolphin meat in Ofunato had died out, and it was transported to the mountains of Tōhoku region, far from the sea. The fishermen considered dolphins only as a commodity, not for eating.[60]

In 1928, a school of dolphins came to Kariya Bay in Saga Prefecture and over 300 were caught. However, this was the last time a large-scale dolphin fishery was conducted in there.[61]

In 1933, dolphins caught in Taiji town were shipped to an aquarium in the Hanshin area for the first time. In 1936, it was brought to Hanshin Koshien Park (amusement park 1929 - 1943.)[22]

The Goto Ethnographic Magazine (五島民族図誌) published in 1934 contains articles and photographs of dolphin fishing in Gotō Islands.[13]

The History of Shizuoka Prefecture (静岡県史) published in 1934 also mentions Tsumara, Koura (now Minamiizu Town), Arari (now Nishiizu Town), and Omaezaki.

Contributors to the dolphin fishery were given dorsal and tail fins. They sometimes ate them and had the custom of displaying them under the eaves for years. Others dedicated them to shrines dedicated to dolphins. In 1936, the "Dolphin Association Statute" was established, specifying that dorsal and caudal fins would be awarded to those who had made meritorious contributions to the fishery.[13]

In Hokkaido, dolphin fishing was conducted in Abashiri.[62]

In 1942, large-scale dolphin migrations began again in Shizuoka Prefecture. A catch of 20,000 was reported in Arari.[63] This is thought to be due to food shortages caused by World War II and the fact that coastal fisheries became the main source of income as large vessels were confiscated by the Japanese military.[64]

End of World War II to 1960s

In 1949, a memorial was built on Fukue Island (Nagasaki Prefecture) on the grounds that dolphins are animals.[65]

From 1950 to 1956, folklorist Tsuneichi Miyamoto conducted research on Tsushima's fishing industry, and after his death, History of Tsushima Fishery was published. In this book, dolphin fishing is mentioned throughout.[16]

In 1951, NHK broadcast a 74-second clip of the pursuit of Short-finned pilot whales. At that time, 40 whales were captured.[66]

In Tsushima Island, the coastal rias are used for drive fishing. Around 1960, about 1,000 dolphins arrived, and for the next several years, 200 - 300 dolphins were caught annually.[67]

In Shizuoka Prefecture, the annual catch peaked in the 1960s with an average of 11,000 animals per year.[68]

In 1969, fishermen in the town of Taiji were asked to catch dolphins for a display at the Whale Museum in the town, and after 12 years of successful fishing.[22] Around this time, dolphin fishing techniques were introduced from Futo and Kawana in Shizuoka Prefecture.[69][22][70]

In Shizuoka Prefecture, from this time on, the number of vessels navigating increased due to economic growth, and the number of fish such as saury and sardines that the dolphins could feed on decreased, so the dolphins stopped coming and the dolphin fishery declined.[71] For this reason, dolphins caught in Iwate and other prefectures are now eaten in Shizuoka Prefecture.[72] In Shizuoka Prefecture, dolphin meat are eaten as miso-broiled. Dolphin meat are cut into bite-sized pieces and stir-fried, burdock root is added and stir-fried further, then seasoned with sake, oy sauce, sugar and miso.[73]

Around 1970, in Nago City, Okinawa Prefecture, dolphin fishing reached its peak,[74] when almost all the boats in the harbor sailed with the strong support of the citizens and the fishing cooperative, catching as many as 250 animals at once.[58]

1970s

On Iki Island in Nagasaki Prefecture, a large-scale pursuit fishery was conducted from 1976 to 1986 for the purpose of vermin control. According to fishermen in Iki Island, since 1965, schools of dolphin have appeared in the surrounding waters and intercepted yellowtails caught on the hooks of pole-and-line fisheries, and the small whales have caused the loss of fish stocks. According to fishermen in the Iki island, schools of dolphins have been appearing in nearby waters since 1965 and have disrupted the fishing industry. After 10 years of attempts to exterminate them by sound intimidation and gunfire with little effect, they had no choice but to introduce drive fishing under the technical guidance of Taiji in Wakayama Prefecture and Futo in Shizuoka Prefecture. Because Iki did not have the custom of eating dolphins, they were used as livestock feed or fertilizer material or were buried on the beach, with the exception of a few.[75] A dedicated grinder was also purchased for feed and fertilizer production. The extermination of cetaceans by drive fishing was said to have had some effect. Fishing for the purpose of vermin control on Iki Island was scaled down after 1986 due to a decrease in the number of dolphins migrating.[76]

Dolphin fishing on Iki Island was condemned by many parts of the world after a video of the capture was released in 1978. Singer Olivia Newton-John postponed her April visit to Japan for her second solo performance. Six months later, after a solo performance, Olivia learned that dolphin fishing was a way for the fishermen of Iki to survive, and during a performance in Japan, she donated $20,000 to the Marine Ecology Research Institute in Chiba Prefecture for research on how dolphins and humans can coexist.[77]。

1980s

In 1980, a foreign activist cut nets to release 250 to 300 dolphins caught in fishing on Iki Island.[75]: 80–81 Peter Singer, a researcher in ethical philosophy, came to Japan from Australia to defend. A Japanese district court sentenced the activist to six months in prison, suspended for three years.[78]

In December 1980, a joint operation between Futo and Kawana was being conducted in Futo, when a small whale escaped by foreign activists.[79]。

Demand for dolphins increased as a substitute for whales around the time of the commercial whaling moratorium. The number of porpoises captured increased from 16,515 in 1986 to 40,367 in 1988. As a result, catch limits were established for each fishing method and for each dolphin species, beginning with the 1991 porpoises.[75]

1990s

On November 2–3, 1990, 582 Risso's dolphin drifted ashore at Shirarake Beach in Gotō Islands, Nagasaki Prefecture. When these were taken and used for food, the Chunichi Shimbun and other Japanese mass media simultaneously reported that the heads were beaten and dismantled for food.[80] The British newspapers reported and condemned it as dolphin slaughter or a disgrace to the whole world.[81] On the other hand, a Japanese weekly defended the dolphins on the Gotō Islands, saying that there was a tradition that dolphins were a gift from the gods and that they were distributed as an important source of protein because they were a remote island.[82]

Although Shizuoka Prefecture was allotted an annual quota of about 600 animals, the annual quota has been less than 100 animals since 1993, and since 1997, the quota has been reduced to 71 animals in 1999.[83]

In 1996, Futo in Shizuoka Prefecture caught 50 False killer whale and sold them for food and to an aquarium, but the Elsa Nature Conservation Society, which monitored the fishing, pointed out that False killer whale were not a species to be caught and demanded that the situation be corrected.[79] Two months later, on December 1, the Izu Shimbun newspaper published a memoir by a fisherman titled Dolphins are eating humans, in which he wrote about the terrible damage to the fishing industry caused by dolphins and the unreasonableness of having to release them.[79]。

2000s

In 2003, the Taiji Fisheries Cooperative Association's counselor said that dolphin fishing is not contrary to the objectives of the International Whaling Commission, that whaling in Taiji is a tradition and drive fishing is an important component, and that whalers in Taiji have been providing food for local residents for generations and will continue to fish in the future.[84]

Dolphin fishing on the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture was discontinued after 2004.[85]

In November 2005, Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare announced its opinion that pregnant women can consume dolphins at a frequency of approximately 80 grams per serving: up to once every two months for Common bottlenose dolphin, once every two weeks for Short-finned pilot whale, and twice a week for Dall's porpoise. At the same time, they also announced that there is no concern about adverse effects of mercury on the health of the general public, including children, as long as they eat normal amounts.[86]

In November 2007, actress Hayden Panettiere and others attempted to save a dolphin about to be driven in the Taiji dolphin fishery by approaching it with surfboards, but failed when the fishermen pushed them away.[87] This scene was used in the 2009 film The Cove.[88]

In 2009, a film The Cove was released criticizing Taiji's dolphin fishery.It was an indictment of the cruel killing of dolphins and the high mercury content of dolphin meat.[89] A July 2009 National Geographic article reported, What he did was by all accounts illegal and dangerous and borderline stupid. But so is killing a dolphin.[90] The film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 82nd Academy Awards in 2010.[91]

After 2010

In September 2010, the nets of a cage used to store captured dolphins were cut at a fishing port in the town of Taiji. According to Japanese police, seven of the eleven cages were cut, leaving a hole of approximately 50 cm to 150 cm. It is believed that the cages was cut with a sharp knife. The European-based conservation group The Black Fish claimed in the same month that it had cut dolphin nets at a fishing port in Taiji Town and rescued many dolphins.[93]

In December 2010, Wakayama Prefecture issued a statement criticizing the film The Cove, saying, "Criticizing dolphin fishing based on one-sided values and misinformation, as this film does, is an unjust act that threatens the livelihood of people who have long been involved in dolphin fishing in Taiji Town and damages the history and pride of the town and must never be allowed. The statement criticized the dolphin fishery as "unjust and unforgivable. [94]

In 2011, the Dolphin Project, founded by Ric O'Barry, called for a JAPAN DOLPHINS DAY on September 1 each year, when dolphin fishing begins in Taiji Town, to organize a positive event in their city, preferably near a Japanese embassy or consulate general.[95]

In 2012, a Sea Shepherd member was arrested by Wakayama Prefectural Police for allegedly hanging onto the harpoon end of a monument to a fisherman with a harpoon in a park in Taiji Town and bending the tip.[96]

In April 2013, the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, a peer-reviewed academic journal, published an article stating that the method of slaughtering dolphins in Taiji Town "does not conform to the recognized requirement for “immediate insensibility” and would not be tolerated or permitted in any regulated slaughterhouse process in the developed world."[97]

In 2013, the number of dolphins caught in drive fishing in Japan was 1,239, which were caught in Taiji Town, Wakayama Prefecture. There were 498 striped dolphins, 298 risso's dolphins, 126 pantropical spotted dolphins, 190 common bottlenose dolphins, 88 pilot whales and 39 pacific white-sided dolphins. And the number of live cetaceans (live dolphins) shipped to aquariums and dolphinariums were 1 striped dolphin, 12 risso's dolphins, 45 pantropical spotted dolphins, 84 common bottlenose dolphins, 1 Pilot whale, and 29 pacific white-sided dolphins.[98] In 2014, 937 dolphins were taken, of which 84 were shipped as live cetaceans.[83]

About 200 activists from anti-whaling groups visited Taiji in 2013.[99]

In January 2014, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy expressed her opinion on Twitter that drive hunt dolphin killing is inhumane.[100]

In February 2014, the Japanese cabinet decided on a written response regarding Japan's dolphin fishery, stating that it is one of the traditional fisheries of our country and is properly conducted in accordance with the law.[101]

In April 2015, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (Waza) suspended the status of the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums (Jaza) for violating its code of ethics on animal welfare by fishing for dolphins. In May, JAWA agreed to stop purchasing dolphins taken in captivity in the town of Taiji, thus avoiding expulsion from WAZA.[102]

The Wakayama Prefectural Government stated, "The dolphin fishery in Taiji Town has been the target of radical animal rights groups coming from abroad on numerous occasions. They repeatedly sabotaging the fishery and psychologically attacking the dolphins."[103][94]

In June 2015, the Kyodo News reported that about half of the live dolphins caught in pursuit fisheries in Taiji Town, Wakayama Prefecture, are exported to China, South Korea, Russia, and other foreign countries. Exports to China amounted to 216 dolphins, 36 to Ukraine, 35 to South Korea, 15 to Russia, and 12 other countries in the last five years, including one to the U.S. The export of dolphins to China is handled by specialized companies. The exports were handled by a specialized company, and the Taiji Fisheries Cooperative was not directly involved.[104]

In June 2015, Wakayama Prefecture Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Committee propose to the Wakayama Prefectural Assembly. That stated "Extreme criticism and dangerous disturbances by the anti-whaling group Sea Shepherd have already continued for more than 10 years. Although the unceasing efforts of the prefectural police and Japan Coast Guard to strengthen their vigilance have helped to calm the situation, the mental and physical pain inflicted by the endless protests is immeasurable."[105] The opinion was approved by all.[106][107]

In December 2016, English actress Maisie Williams visited Taiji Town, Wakayama Prefecture, to protest dolphin drive fishing.[108]

In January 2017, someone cut the net of a dolphin cage at a leisure facility in Taiji, Wakayama Prefecture, causing four dolphins to get out, but three returned to the cage on their own.[108]

In October 2017, a man and a woman, a Dutch and a Belgian, jumped into the pool where a dolphin show was being held at [[ Adventure World (Japan)| Adventure World]], a leisure facility in Wakayama Prefecture, and held placards in the water protesting dolphin fishing, disrupting the show. A fellow man videotaped it, and the three were arrested by prefectural police on charges of obstruction of business.[109]

In 2017, 50 activists from anti-whaling groups were identified in the town of Taiji in Wakayama Prefecture.[99]

In 2019, Itō's fishery cooperative lifted the ban on dolphin drive fishing, which had been suspended since 2004, to keep the tradition of dolphin fishing alive, but only for capturing live animals for sale to aquariums and other institutions.[110]

Japanese dolphin catches for the 2022 fishing season were 10,950 in total, 745 in Hokkaido, 7,757 in Iwate, 141 in Miyagi, 2,210 in Wakayama, and 97 in Okinawa. The highest number of captured was 8,535 in Dall's porpoise.[92]

References

- ^ a b 天野努『図説 安房の歴史』

- ^ 村山:2009

- ^ a b 中村 2011, p. 304.

- ^ "真脇遺跡 - 遺跡の環境". Archived from the original on 2014-04-02. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- ^ 入江高砂貝塚館(洞爺湖町)

- ^ 神奈川県教育委員会 2019年『縄文の海 縄文の森』平成27年(2019年)度かながわの遺跡展・巡回展図録 pp.8-14

- ^ 横浜市歴史博物館 2016年『称名寺貝塚 土器とイルカと縄文人』横浜市歴史博物館 平成27年(2015年)度企画展

- ^ 小野, 真一; 竹田, 伸一; 秋本, 真澄 (1983-03-30). 伊豆井戸川遺跡. 静岡県伊東市和田町.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 国学院大学. "神名データベース 伊奢沙和気大神之命". Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ a b c 岡田 2019, p. 61.

- ^ 板橋 2002, p. 93.

- ^ 【2004年度調査報告】 - 立教大学

- ^ a b c 中村 2005.

- ^ コトバンク. "建切網". Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ^ a b 中村 2006, p. 449.

- ^ a b 中村 2006, p. 450.

- ^ 岩永紘和 (2023). "『言継卿記』に見る一六世紀の魚介類消費". 琵琶湖博物館研究調査報告. 36: 139.

- ^ 山科言継 (1914). "言継卿記 第三". Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ 中村 2012, p. 122.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 448.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 447.

- ^ a b c d 遠藤愛子 (2011). "捕鯨・ナマコと国際社会 : 変容する鯨類資源の利用実態 : 和歌山県太地町の小規模沿岸捕鯨業を事例として". 国立民族学博物館調査報告. 97 (97). 国立民族学博物館: 237–267. doi:10.15021/00000996. ISSN 1340-6787.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 446.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 442.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 12.

- ^ 宇野修平『陸前唐桑の史料』(1955)

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 444.

- ^ 板橋 2002, p. 82.

- ^ 中村 2008, p. 256.

- ^ 中村 2007, p. 262.

- ^ 中村 2007, p. 257.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 437.

- ^ 和田 2004, p. 14.

- ^ 森弘子 (2014). "西海捕鯨絵巻の特徴 ―紀州地方の捕鯨絵巻との比較から―". 西南学院大学国際文化論集. 26 (2). 西南学院大学学術研究所: 117–155. ISSN 0913-0756.

- ^ 『肥前国産物図考』:海豚漁事・鮪網之図・鯛網・海士 Archived 2015-07-11 at the Wayback Machine国立公文書館デジタルアーカイブ:重要文化財等コンテンツ

- ^ 中村 2005, p. 380.

- ^ 宇仁義和 (2012-09-03). "近世文献に見る北海道の鯨類利用" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ 児島恭子 (2013-10-22). "アイヌの捕鯨文化". 国際常民文化研究機構: 115–121.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 438.

- ^ 伊藤 康宏 (1995). 日本農書全集. Vol. 58. 農山漁村文化協会. pp. 124, 142. ISBN 978-4540950049.

- ^ 中村 2007, p. 256.

- ^ 和田 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b 中村 2007, p. 255.

- ^ a b 和田 2004, p. 18.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 30.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 12,13.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 16-21.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 21.

- ^ 中村 2007, p. 252.

- ^ 浜中栄吉, ed. (1979). 太地町史. 太地町. p. 493.

- ^ 粕谷俊雄 (2011). イルカ―小型鯨類の保全生物学. 東京大学出版会. p. 119. ISBN 978-4130661607.

- ^ 中村 2006, p. 424.

- ^ 中村 2007, p. 248.

- ^ a b 『日本百科大事典』第1巻、1908年(The reference is to a 1988 reprint by the Famous Books Popularization Society ISBN 4-89551-358-0)The section on "The Dolphin."

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 34.

- ^ a b c 琉球新報社編『最新版 沖縄コンパクト事典』琉球新報社 2003年 ISBN 4-89742-050-4 Section "ひーとぅがり"

- ^ 水産庁 平成17年 小型鯨類の漁業と資源調査(PDF) Archived 2007-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b 沖縄県水産試験場編『沖縄県の漁具漁法』(財)沖縄県漁業振興基金発行 1986 p.216

- ^ 和田 2004, p. 36.

- ^ 中村 2008, p. 229.

- ^ 中村 2005, p. 383.

- ^ 宇仁義和 (2001). "北海道近海の近代海獣猟業の統計と関連資料". 知床博物館研究報告22: 81.

- ^ 和田 2004, p. 39.

- ^ 岡田 2019, p. 59.

- ^ 中村 2005, p. 370.

- ^ 宇仁義和 (2014). "NHKアーカイブス保存映像の文化人類族学的調査の可能性" (PDF). 北海道民族学 (10). 北海道民族学会: 77–86. ISSN 1881-0047.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 38.

- ^ 和田 2004.

- ^ 川島 2008, p. 26.

- ^ 松本博之 (2011). "海洋環境保全の人類学". 国立民族学博物館調査報告. 97 (97). 国立民族学博物館: 3–19. doi:10.15021/00000986. ISSN 1340-6787.

- ^ 岡田 2019, p. 60.

- ^ 岡田 2019, p. 57.

- ^ 三島市郷土資料館 (2004-12-01). "伊豆の家庭料理 イルカの味噌煮". Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- ^ ピトゥと名護人. 名護博物館. 1994.

- ^ a b c 川端裕人 (1997). イルカとぼくらの微妙な関係. 時事通信社. p. 73.

- ^ イルカの追い込み猟を巡る最近の動向 エルザ会報No.126(2004年2月10日発行)

- ^ 『海からの使者イルカ』藤原英司 朝日新聞社 261頁 ISBN 402260770X

- ^ 村山司 (2009). イルカ―生態、六感、人との関わり. 中央公論新社. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-4121020185.

- ^ a b c 板橋悦子 (2003). "<研究ノート>静岡県におけるイルカ漁・イルカ食の現状". 常民文化 (26). 成城大学: 41–62. ISSN 0388-8908.

- ^ ストランディングデータベース - 長崎県 公益財団法人 下関海洋科学アカデミー鯨類研究室

- ^ 中村 2005, p. 378.

- ^ 中村 2005, p. 377.

- ^ a b "和歌山県:来期も同じイルカ漁獲枠 知事「削減考えなし」". Mainichi Shimbun. 2015-05-26. Archived from the original on 2015-05-27.

- ^ Cypress.ne.jp, article retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "「イルカ漁などで保留」から2年、伊豆半島ジオパーク世界加盟「再審査」へ". THE PAGE. 2017-06-02. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ 厚生労働省医薬食品局食品安全部基準審査課長 (2005-11-02). "妊婦への魚介類の摂食と水銀に関する注意事項について". Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Protests against Japan's slaughter of porpoises". Telegraph.co.uk. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Top 10 Celebrity Protesters". TIME. 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Exposing ugly secrets". Los Angeles Times. 2009-07-31. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "The Cove: Filmmaker's Team Infiltrates Japan's Dolphin Slaughter". National Geographic. 2009-07-15. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Nominees for the 82nd Academy Awards" Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ a b 水産庁 (2023). "捕鯨をめぐる情勢" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "イルカ保管の網切られる 和歌山・太地町、海外保護団体が声明". 産経ニュース. 2010-09-29. Archived from the original on 2010-10-02. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ a b イルカ漁等に対する和歌山県の見解(項目追記) 和歌山県ホームページ

- ^ Dolphin Project (2011-07-05). "CELEBRATE JAPAN DOLPHINS DAY". Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "漁師像を損壊の疑い、反捕鯨団体員を逮捕 和歌山・太地町". 日本経済新聞. 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ Andrew Butterworth, Philippa Brakes, Courtney S. Vail &Diana Reiss (2013-04-01). "A Veterinary and Behavioral Analysis of Dolphin Killing Methods Currently Used in the "Drive Hunt" in Taiji, Japan". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science: 184–204.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 国立研究開発法人 水産研究・教育機構 (2015). "小型鯨類の漁業と資源調査(総説)" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ a b "反捕鯨活動家が減少 イルカ漁9月1日解禁". 毎日新聞. 2018-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Japan officials defend dolphin hunting at Taiji Cove". CNN. 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "「イルカ漁は適切」政府が答弁書を決定 「わが国の伝統的な漁業」". 産経ニュース. 2014-02-25. Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Japan aquariums to stop taking dolphins from annual Taiji hunt". CNN. 2015-05-21. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ イルカ漁への和歌山県の見解を記した文書が素晴らしいと話題に BIGLOBEニュース編集部, 2015年5月27日]

- ^ "追い込み漁の太地イルカ、半数は海外に輸出". 日本経済新聞. 2015-06-08. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "捕鯨とイルカ漁業への妨害や不当な圧力に対する抗議と地域食文化を継承するための措置を求める意見書" (PDF). 2005-06-26. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "和歌山県議会 意見書・決議案(第18期分)". Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "イルカ漁への圧力に抗議 和歌山県議会が意見書可決". 産経新聞. 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ a b "いけすの網切られ外に出たイルカ、3頭戻り 和歌山県太地町". BBC. 2017-01-05. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "まるで英雄気取り、イルカショー妨害の外国人男女…犯行予告にビデオ撮影、逮捕後も反省なし". 産経新聞. 2017-11-20. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ 農林水産省. "イルカの味噌煮". Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- 和田雄剛 (2004). 静岡いるか漁ひと物語. 静岡郷土史研究会(国会図書館蔵).

- 辺見栄 (2005). 日本のイルカ追い込み猟の現状. エルザ自然保護の会(国会図書館蔵).

- 名護博物館 (1994). ピトゥと名護人. 名護博物館(国会図書館蔵).

- 村山司 (2009). イルカ. 中公新書. ISBN 978-4-12-102018-5.

- 日本鯨類研究所 編 (2007). "日本伝統捕鯨地域サミット 開催の記録". 日本鯨類研究所. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- 濱岡伸也ら校注・執筆 (1995). 日本農書全集58. 農山漁村文化協会. ISBN 4-540-95004-5.

- 天野努監修 (2009). 図説 安房の歴史. 郷土出版社. ISBN 978-4-86375-053-1.

- 川島秀一 (2008). 追込漁. 法政大学出版局. ISBN 978-4-588-21421-9.

- 秋道知彌編著 (1995). イルカとナマコと海人たち. 日本放送出版協会. ISBN 4-14-001745-7.

- 関口雄祐 (2010). イルカを食べちゃダメですか?. 光文社. ISBN 978-4-334-03576-1.

- 中村羊一郎 (2006). "対馬におけるイルカ漁の歴史と民俗". 静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要 (8). 静岡産業大学情報学部: 452–407. This paper is in descending order of page numbers because it appears at the end of a left-opening journal volume as a right-opening paper.

- 中村羊一郎 (2005). "玄海灘におけるイルカ漁と漁業組織". 静岡産業大学国際情報学部研究紀要 (7). 静岡産業大学国際情報学部: 386–341.This paper is in descending order of page numbers.

- 中村羊一郎 (2007). "陸中海岸におけるイルカ漁の歴史と民俗 (上)". 静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要 (9). 静岡産業大学情報学部: 226–225.This paper is in descending order of page numbers.

- 中村羊一郎 (2008). "陸中海岸におけるイルカ漁の歴史と民俗 (下)". 静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要 (10). 静岡産業大学情報学部: 262–221.This paper is in descending order of page numbers.

- 中村羊一郎 (2011-03-01). "丹後国伊根におけるイルカ漁と漁株制". 静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要: 272–314.This paper is in descending order of page numbers.

- 中村羊一郎 (2012-03-01). "沼津市浦及び西伊豆町田子におけるイルカ追込み漁について". 静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要: 125–103.This paper is in descending order of page numbers.

- 岡田 夕佳, 丸山 真史 (2019-12-26). "静岡県におけるイルカの食文化と消費動向" (PDF). 東海大学紀要海洋学部: 57–65.

- 板橋悦子 (2002). "近世におけるイルカ食の効能". 常民文化: 96–79. This paper is in descending order of page numbers.