History of brewing in Rochester, New York

The city of Rochester, New York—before being known as the birthplace of Kodak, Xerox, and Bausch & Lomb—was internationally known for its robust brewing industry. Indeed, the city was uniquely positioned for such an industry in the early 19th century. The corn, rye, barley, wheat, and other grains grown in the Genesee River Valley were shipped down river to be milled in such quantity that by 1838 Rochester was world's largest flour producer, earning it the nickname the Flour City.

When the Erie Canal opened in Rochester in 1823 the city became a true western Boomtown, growing from a population of 9,200 in 1821 to 36,000 by 1850—a year in which the city has at least 20 breweries in operation.[1] The emergence of the canal also allowed for the easy delivery of hops, grown to such an extent in area the between Albany and Syracuse that by 1849 the region produced more than anywhere else in the country, eventually selling more than three million pounds annually by 1855.[2][3]

A large influx of German immigrants escaping famine and war in the late 1840s also contributed to the industry's growth.[4] During the 1850s another dozen breweries began operating. By 1880, 13 breweries produced a product valued at $1,411,000. By the early 20th century, brewing was an immensely successful industry in the city. In 1901 470,000 barrels of beer and another 105,000 barrels of ale were produced.[5] In 1909 nine major breweries supplied not only the local market, but the entire northeast.

While the breweries themselves were large employers, they also supported a number of other industries including bottlers; salesmen; teamsters; ice cutters; farmers growing wheat, barley, and hops; tavern keepers; lithographers (for labels); wagon makers and horsemen. In turn, the sale of brewery grain to farmers brought about $100,000 to local brewers. Beer was applauded by brewers and many doctors as healthy a liquid bread.[6][7]

Prohibition shuttered the Rochester brewing scene in 1919. After Prohibition, only five breweries would reopen in Rochester. By 1970, only the Genesee Brewing Company was left.

Today, more than a dozen independent craft brewers operate in the City of Rochester, and another two dozen within Monroe County.

Pre-prohibition

- 1819 The first person known to brew beer in the village of Rochester on any scale was Nathan Lyman, nephew of Red Mill owner Hervey Eli.[8] He did so with water taken from a natural spring around the area where St Paul St and Central Avenue meet to his home on Water Street close to the present day Main Street Bridge.[6] Subsequent city directories list the address of Lyman's brewery as "south end of Water Street" (1834), "East end of the aqueduct" (1838), 17 Water Street (1841), and 40 South St. Paul St. (1844). The address of the spring is listed as 67 North St. Paul St. by a later purchase of that property.

- 1824 A January advertisement in the Rochester Telegraph promotes cash paid for corn, rye, and barley by Captain Ely's Brewery.[9] In October, Reuben Bennet, of Manilus, repairs and extends an existing brewery owned by Ely & Ensworth,[10] likely located on the site of the present Powers Building.[11] Other advertisements that year note “Cash paid for Barley at the new brewery at the east end of the aqueduct," “fresh yeast for sale” and “malting done on short notice.”

- 1825 A Rochester Telegraph article describing a recent census notes the village has two breweries in operation.[12]

- 1826 An advertisement for a brewery operated by Stebbins and Doyle serving Bennet's Beer appears.[13] An 1829 advert locates the brewery next door to a tannery located at 8 Buffalo St, near Water St.[14]

- 1834 John and Gabriel Longmuir establish a brewery at 8 North Water Street, later identified as Rochester Brewery.[15] In 1837 a natural spring is discovered on the brothers’ property; Longmuir Springs and Baths opens to the public in a building adjoining the brewery.[16]

- 1838 Matthias Sparks takes over operation of City Springs Brewery from Richard Cristie.[17]

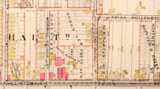

- 1840 Samuel Warren establishes City Spring Brewery, so called because of a fresh water spring just east of the establishment, likely the same spring from which Nathan Lyman used. The brewery was located on a block bounded by Central Ave. and Water, River, and North St. Paul Strs., currently part of the Inner Loop (see map below). Warren is said to be to the first to introduce pale ale to Rochester. Warren died in January 1844 and passed the brewery to his son, Edward K. Warren, who in turn passed it to his son, Edward C. Warren. By 1848 the brewery employs 20 men and brews 75 barrels per week.[18] In 1885 a new building is erected.[19] On July 1, 1893, the E.K. Warren Brewery Company was incorporated with a capital stock of $35,000.[20] Warren's Champagne Ale and Burton Ale were specialties. In 1877 the brewery employed 15 men and produced 9,000 barrels; by 1894, it was producing 20,000 barrels annually.[21][22] James Hanley purchases the brewery in August, 1899.[23] Nathan Lyman no longer appears in the City Directory.

- 1841 George Marburger establishes his brewery along a single-track railway at 80 Clinton Avenue North. In 1848 he is put in charge of Marburger Brothers, a company composed of himself and Jacob and Louis Marburger. In 1849 Charles Rau is hired as brewmaster. George dies in 1854 leaving his widow, Elizabeth and brother, Jacob, in control. When Jacob and Elizabeth Rau move on to other ventures, Jacob Marburger partners with George Spies, forming Marburger & Spies Brewery on the site. The buildings were demolished in 1881 in favor of a new train station for Central Railway.[24][4][25]

- 1849 Louis Bauer constructs a brewery on Lyell Street, just west of the canal, near the bridge, which operates for 20 years.[26] In 1870 his son, Louis Bauer Jr., takes charge, partnering with George B. Swikehard to form Louis Bauer Jr. and Company. Bauer Jr. relocates to 23 Hudson Avenue the next year but is out business by 1873. Swikehard stays at the Lyell facility until 1874; in 1875 the City Directory lists him as a brewer at the Rochester Brewery. In 1881, Bauer Sr. sells the brewery building to H. Likely and Co., trunk manufacturer.[27]

- 1852 Henry Bartholomay comes to Rochester, entering into business with Phillip Wills. On December 7 their brewery serves the first glass of lager beer produced in Rochester.

- 1852 Frederick Miller establishes a brewery on Brown Street. In 1861 he purchased a new site on Lake Avenue and built a new facility. The original building was destroyed in fire in 1869 and rebuilt, only to burn down again in 1876,[28] again being rebuilt.[6] In 1883 the Miller Brewery Company was incorporated. The company added an ale house in 1889 and later introduced its famous Acme Ale. Its name was changed to Flower City Brewing in 1902 and would operate until Prohibition.[29][30][31][32]

- 1853 Jacob Baetzel opens a brewery on the corner of North Clinton and Marietta Streets, later listed as 86 N Clinton. In 1864, the brewery in located on N Clinton near Clifford, listed, in 1888, as 855 N Clinton. Baetzel dies 16 June 1870. His son, J. George Baetzel resumes the business and, in 1890, is vice-president of the Union Brewing Company, operating in the same facility; he dies May 24, 1892.

- 1855 Frederick Loebs and Christian Meyer establish Meyer & Loebs Brewery on the corner of Hudson and Merrimac. In 1879, the name is changed to Lion Brewing Company and Loebs's son, Frederick C. Loebs, joins the firm;[33] in 1885, it is called Loebs Brothers. Finally, in 1889, it is incorporated under the name American Brewing Company (ABC); a new facility is built, designed by Adam C. Wagner, and brews until Prohibition.[6][34] In 1898 an ale brewery is erected. By 1903 capacity 100,000 barrels;[35] by 1907, 200,000 barrels. ABC's bottled beer takes prizes at the 1900 Paris Exposition and the 1901 the Marseilles Fair. Standard Brewing is also incorporated, initially brewing only in bulk.[30]

- 1856 Charles Rau, now-husband to George Marburger's widow, Elizabeth, establishes Jacob Rau Brewing on St. Paul Street.[4] He later takes on a partner to form Rau & Reisky. In 1874 the brewery becomes known as Reisky & Spies.[30]

- 1858 Patrick Enright establishes Enright Brewing Company at 149 Mill Street on the corner Factory Street. According to The Western Brewer, in 1879 the brewery sells 3,333 barrels of beer. Patrick dies 25 June 1883, at which point his son, Thomas J. Enright, takes over.[36] In 1887 Michael P. Enright is in charge and three stories are added.[37][38] The brewery is sold to Frank H. Falls in 1905 for $50,000[39][40] and operates until 1907.[41][6][30] Parts of the Enright Brewery were used in construction of the brewery at the Genesee Country Village and Museum, though that structure burned down in 1888.[42]

- 1860 Joseph Nunn opens a brewery at 347 Brown Street, on the corner of Wentworth, which operates until 1890 when Nunn founds Nunn Brass Works.[43] The building still stands as 641 Brown Street.

- 1861 Joseph Yaman, previously a baker, opens a brewery at 247 Exchange Street, on the north side of the Clarissa Street Bridge. In 1864 he moves his operations to 120 Jay Street, on the corner of Saxton (now 446 Jay Street). From 1880 to 1881 he brings on John Kase as a partner. Kase then opens his own brewery on the corner of Colvin and Syke Streets. The Yaman brewery operates until 1889.[44]

- 1863 Frank Weinmann opens a brewery on Jay Street, near Whitney—the address changes over the years from 35 to 351 and finally to 635. Frank dies in March 1876 and his wife, Margaret, takes over operating the brewery until she retires in 1889 when their son, Charles G., takes control the brewery until 1911, when the brewery ceases operations.

- 1864 The Longmuir brothers sell their brewery to Charles Gordon who partners with Henry H. Bevier, forming H.H. Bevier & Co.. In 1869 H. B. Hathaway entered the partnership.[45][46] A new building is erected on Water Street connecting it with the older brewery building by underground tunnel. They later build a stable for 32 horses in order to deliver beer throughout the city. It is the first stable in Rochester in which the horses sleep on the second floor. Bevier died 1872 and the firm changed its name to Hathaway and Gordon. Upon his death Bevier left a sum of money to his wife, Susan, who, upon her death in 1903, left a gift of more than $300,000 to the Mechanics Institute—predecessor to Rochester Institute of Technology—for the construction of the Bevier Memorial Building, built on the site of Nathaniel Rochester's second home in the village.[47][6][48]

- 1864 William Miller first appears as a brewer on North Avenue (now Portland) near German Street (now Central Park) and Draper Street. The address is later listed as 58 North Avenue. A Union and Advertiser article from December 30, 1876, notes the brewery was “destroyed by fire this morning.”

- 1868 Jacob Rauber and George Meyer (sometimes spelled Mayer) establish their brewery at 111 North St. Paul Street, previously occupied by the Rau brewery. In 1873 Rauber retires due to ill health and the business is sold to Emil Reisky and Henry Spies[49] who operate the Reisky and Spies brewery until 1878. Meyer operates his own brewery on Cottage Street near Exchange from 1873 to 1876,[50] briefly taking on Charles Seiler as a partner before becoming a brewer at Frederick Miller's Lake Avenue brewery.

- 1874 Henry Bartholomay organizes the Bartholomay Brewing Company with a capital stock of $250,000. He opens a modern facility on St. Paul St. near Vincent on the eastern bluffs of the Genesee River. Its first year of production saw 3,000 barrels; and 125,000 in the next. The malt house had a capacity of 25,000 bushels. By 1890, the annual production is 350,000 barrels of beer with a malting capacity of 200,000 bushels.[51] The company would eventually have offices in New York City, Boston, and Baltimore. At one point in the 1880s it operated the largest ice house in New York State.[4]

- 1874 The Rochester Brewing Company is founded on Cliff Street. By 1884 the brewery is producing approximately 75,000 barrels and distributing to Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Maryland among other places.[52] In 1889 it begins operating as a branch of Bartholomay Brewing. By 1890, it is selling 130,000 barrels per year in US and foreign markets. The brewery's capacity that year is 225,000 barrels, with the ability to store 60,000 barrels in their cellars.[51] By 1902 it is independent once more and continues to operate until Prohibition.[53]

- 1874 The Boehm and Zimmerman brewery first appears in the City Directory. Census records indicate the two—John Boehm and George Zimmerman—were neighbors and brewers in Gates before the Rochester venture. By 1876 the two are listed as brewers at separate locations (Boehm on the corner of Colvin and Maple; Zimmerman on the corner of Colvin and Syke—one block apart). John Boehm no longer appears as a brewer after 1877 and Zimmerman remains in business until his death in May 1881.

- 1877 Rochester Ale Company opens briefly on Lyell Street on the site of Louis Bauer's brewery.[54]

- 1878 Mathias Kondolf takes charge of Reisky & Spies, organizes a stock company and changes its name to the Genesee Brewing Company.[30]

- 1879 The Western Brewer reports annual barrel sales of Rochester breweries as follows: Bartholomay Brewing, 61,824; Genesee Brewing Company, 9,579; Rochester Brewing Company, 50,724; Frederick Miller, 5,805; Marburger & Spies, 2,805.[55]

- 1880 Thirteen breweries in Rochester produced a product valued at $1,411,000, approximately $41M 2021 dollars.[56]

- 1882 The Rochester Brewers Association is founded.[35]

- 1884 Casper Pfaudler, an apprentice at Bartholomay Brewing, invents vacuum fermentation, called the F.F. Vacuum Process, and organizes the Pfaudler Vacuum Fermentation Process Co. The system speeds up the process of fermentation by means of vacuum in glass-lined, steel containers. The process transforms the systems for the handling, storing, and transportation of beer and is installed in breweries across America and in Europe.[35][57]

- 1884 Reported annual barrel sales of Rochester breweries are as follows: Bartholomay Brewery, 150,000; Rochester Brewing Company, 75,000; Genesee Brewing Company, 45,000; Miller Brewing Company, 20,000; Hathaway & Gordon, 10,000; E.K. Warren & Son (City Spring), 8,000.[58]

- 1889 A British syndicate known as the City of London Contract Corporation Limited purchases the Bartholomay, Genesee, and Rochester Brewing companies. It is organized under the name Bartholomay Brewing Company, though each company keeps its own name.[59]

- 1889 Standard Brewing opens at 13 Cataract Street at the end of Platt St., not far from the Genesee Brewing Company.[60] It is built by famed brewery architect Adam C. Wagner.[61] By 1903 it was brewing 40,000 barrels per year.[35]

- 1890 Bartholomay and Rochester Breweries began to using water from the Genesee River for icemaking and other maintenance, a practice which saves The Rochester Brewery approximately $65 per day. The Bartholomay and Genesee Breweries dig wells into the river bed with a capacity of 160,000 gallons. The water is naturally filtered and kept cool by the rock.[6][62]

- 1891 Staub & Angele begins brewing on Wentworth, near Brown Streets. John Staub dies in January 1892 at the age of 25 and operations cease. George Angele dies a few years later at 31.

- 1892 George Emich partners with 3 different men (Charles Müller, George Myer, and Charles Miller) between 1892 and 1897—also on Wentworth near Brown Streets—to form Emich & Müller (1892–93), Emich & Myer (1894–96), and Emich & Miller (1897).

- 1898 Burton Brewing Company begins operation at 23 Wentworth Street—formerly the Nunn brewery—established by father and son Charles and Henry Malleson.[63] It is incorporated with a capital stock of $20,000 in June 1901[64] and operates until 1905.

- 1899 Rochester Chamber of Commerce reports that for the year ending April 1899, 470,000 barrels of beer and 68,000 barrels of ale are brewed in the city, and more than 650 people are employed in the industry.[65]

- 1899 Monroe Brewing Company is formed from a purchase of Union Brewing. It is located at 855 N Clinton, the site of the Baetzel Brewery.[66] In 1915 the address is listed as 1121 Clinton Avenue North, though appears to be the same location; the company is dissolved in 1927.[67] The location is now occupied by Hickey Freeman.

- 1908 Mattias Kondolf opens the Moerlbach Brewery on Emerson Street (in what was then the Town of Gates) with a capacity of 100,000 barrels per year.[68][69][70][71][72] It is shuttered as a result of Prohibition.[48]

- 1917 The seven remaining Rochester breweries, with a combined capital stock of just under $3M, directly employ 614 persons, who collect $625,000 in combined wages. Nearly $7M is estimated to be invested in the total beer and liquor trade in Rochester with about $2.5M being paid in taxes. Rochester breweries pay $82,000 per year in local taxes.[73]

- 1918 Even before passage of the 18th Amendment, the War-Time Prohibition Act ordered that all breweries stop brewing beer, ostensibly to conserve manpower while increasing efficiency of war materials production. At the time, Rochester breweries had an estimated 200,000 barrels on hand.[74] The Flower City Brewing Company incorporates Qualtop Beverages and begins to manufacture non-alcoholic drinks under that name.[75]

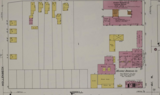

Maps of Brewery Locations

- Lyman Brewery (1820)

- Louis Bauer's Brewery, Lyell Street. (1851)

- Burtis & Symes, S Water (1851)

- Marburger Brewery (1851)

- Baetzel Brewery (1875)

- Bartholomay, Oothout, and Rau Breweries (1875)

- Bauer Brewery (1875)

- Boehm Brewery, Colvin Street (1875)

- City Spring Brewery (1875)

- Enright Brewery, Mill Street (1875)

- Joseph Yaman Brewery, Jay Street, 1875

- Marburger Brewery in 1875

- Joseph Nunn Brewery, Brown Street (1875)

- William Miller's brewery, North Ave. 1875

- Miller Brewing Company Lake Avenue (1888)

- American Brewing Co., Hudson Avenue (1892)

- Nunn Brewery (1892)

- Rochester Brewing Co., Cliff Street (1892)

- Union Brewing (1892)

- Monroe Brewing Company (1900)

- Rochester Brewing Company, Cliff Street (1900)

- American Brewing Company, Hudson Avenue (1910)

- Moerlbach Brewing Company (1910)

- Monroe Brewing Co., Clinton Avenue North (1911)

- Standard Brewing, Lake Avenue (1950)

Post-prohibition

There were at least seven breweries operating in Rochester as the 18th amendment ended production of most alcohol. Some successfully converted to other industries. Bartholomay, for example, converted to dairy production, introducing Bartholomay Quality Ice Cream in July 1919.[76] The American Brewing Company changed its name to Rochester Food Products Corporation and sold malt extract, apple cider, vinegar, and Rochester Special “near beer,” a legal product that contained less than 0.05% alcohol.

- 1932 Louis Wehle, a former brewmaster at Genesee Brewing Company (as well as an assistant brewmaster at Bartholomay Brewing), purchases the brewery buildings and recipes and hires many former employees, incorporating the business on July 8.[77][78] On April 29, 1933, Genesee sold their first brew, their famous Liebotschaner.[79][80] The first year's production totaled approximately 150,000 barrels and by 1934 Wehle had nearly 1,000 employees.[6]

- 1933 On March 22, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Cullen–Harrison Act, authorizing the sale of 3.2 percent beer and wine.

- 1933 ABC reopens as a brewery and introduces its most well-known label, Tam O’Shanter. Other ABC brands include American Bock Beer, American Porter, Apollo Beer, Liberty Beer and Seneca Ale. The brewery closes in June, 1950. Standard Brewing Company reopens at 436 Lake Avenue, in the old Flower City Brewery. Cataract Brewery opens at 13 Cataract Street, the former location of Standard Brewing. It closed in 1940.[81]

- 1934 Rochester Brewing Company reopens at 777 Emerson St and introduces Old Topper Ale, which it brewed until 1970 when the brewery closed down. Topper was then brewed the Eastern Brewing Company of New Jersey.[82]

- 1956 Rochester Brewing Company merges with Standard Brewing Company, creating Rochester-Standard Brewing Company. Standard Brewing's Lake Ave location closes and all brewing in consolidated on Emerson St. This brewery closes in 1970, leaving the Genesee Brewing Company as Rochester's sole brewer.[83][84][85]

See also

References

- ^ McDaniels, Skeeter (2008). Brewed in Rochester A Photographic History of Beer in Rochester, NY 1885-1975. Rochester, NY: Mountain Air Books. ISBN 9780615249414.

- ^ Robinson, Alex (25 July 2019). "New York Farmers Hope To Discover New Hops". Modern Farmer. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Baur, JOe (24 October 2013). "New York State: America's Former Hop Capital". craftbeer.com. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Pfaefflin, Hermann; Wallenberg, Rudolf; Swinney, H.J. (2007). A 100-Year History of the German Community in Rochester, NY 1815-1915. Rochester, NY: The Federation of German-American Societies. ISBN 9780615163352

- ^ Rochester: The Power City 1900-1901. Rochester, NY: Rochester Chamber of Commerce. 1901. p. 169.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rosenberg-Naparsteck, Ruth (1992). "A Brief History of Brewing in Rochester" (PDF). Rochester History. LIV (2). Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ McKelvey, Blake (January 1958). "The Germans of Rochester Their Traditions and Contributions" (PDF). Rochester History. 20 (1).

- ^ Ely, Heman (1885). Records of the Descendants of Nathaniel Ely. Cleveland, Ohio: Short & Porman, Printers and Stationers. pp. 174, 71, 34. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "To Farmers". Rochester Telegraph. 13 January 1824. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Rochester Brewery". Rochester Telegraph. 26 October 1824. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Walking Tour of Rochester's One Hundred Acre Plot". lowerfalls.org. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Our Village". No. 15 February 1825. Rochester Telegraph. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Rochester Brewery". Rochester Telegraph. 16 January 1827. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Sheep Skins Wanted". Rochester Antimasonic Inquirer. 15 September 1829. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Rochester Directory (PDF). Rochester, NY: C. & M. Morse. 1834. p. 60.

- ^ "Rochester Mineral Springs and Bath". Rochester Republican. 6 June 1837. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "City Springs Brewery". Rochester Republican. 22 May 1838. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Warren Brewery". Rochester Daily American. 6 May 1848. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Warren". Democrat and Chronicle. 13 December 1885. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Doing a Good Business". Democrat and Chronicle. 23 May 1896. p. 16. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ History and Commerce of Rochester Illustrated, 1894. New York: A.F. Parsons Publishing Company. 1894. p. 84. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ McIntosh, W.H. (1877). History of Monroe County, NY. Philadelphia: Everts, Ensign, and Everts. p. 119. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Warren Brewery Sold". Democrat and Chronicle. 23 August 1889. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "German News". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (1871-1884). Vol. 49, no. 240. Rochester Publishing Company. August 28, 1881. ProQuest 1924297108. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Old New York Central railroad station". Monroe County Library. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Pfaefflin, Hermann; Wallenberg, Rudolf; Swinney, H.J. (2007). A 100-Year History of the German Community in Rochester, NY 1815-1915. Rochester, NY: The Federation of German-American Societies. ISBN 9780615163352.

- ^ "Bought for a Factory". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (1871-1884). 31 August 1881. ProQuest 1924297822. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Brewery Burned". Vol. 44, no. 179. Democrat and Chronicle. 27 July 1876. p. 4. ProQuest 1924172455. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "Brewery to Change Its Name". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 13 August 1902. ProQuest 1926390883. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e A History of the Brewery and Liquor Industry of Rochester, NY (PDF). Rochester, NY: The Kearse Publishing Company. 1907. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Rochester and Monroe County Pictorial and Biographical (PDF). New York and Chicago: The Pioneer Publishing Co. 1908. pp. 199–201. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Peck, William (1908). History of Rochester and Monroe County, New York From the Earliest Historic Times to the Beginning of 1907. New York and Chicago: The Pioneer Publishing Co. pp. 555–6. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ The Industrial Advance of Rochester: A Historical, Statistical, and Descriptive Review. National Publishing Company. 1884. p. 123. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ "New Brewing Company". Democrat and Chronicle. 9 July 1889. p. 7. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d One Hundred Years of Brewing A Complete History of the Progress Made in the Art, Science and Industry of Brewing in the World, Particularly During the Nineteenth Century. Chicago and New York: H.S. Rich and Co. 1903. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ The Rochester Directory (PDF). Rochester, NY: Drew, Allis & Company. 1884. p. 194. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Building Notes". Democrat and Chronicle. 23 November 1887. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Mortuary Calendar". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 28 June 1889. ProQuest 1924545730. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Enright Brewery Changes Hands". Democrat and Chronicle. 1 April 1905. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Enright & Co". Democrat and Chronicle. 24 September 1905. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Enright Brewery Closes Plant". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 23 September 1907. ProQuest 1925496725. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Polmenteer, Vaughn (9 July 1978). "Genesee Country Museum". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). ProQuest 1937299205. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Joseph Nunn". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). Rochester Printing Company. 28 February 1904. ProQuest 1925438748. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Honored by His Friends: Supervisor Joseph Yawman Observes his Golden Wedding". Democrat and Chronicle. 29 May 1888. ProQuest 1924517438. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Notice of Sale in Partition". Democrat and Chronicle. 29 June 1915. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Extension Across River". Democrat and Chronicle. 22 April 1906. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Walking Tour of Rochester's One Hundred Acre Plot". lowerfalls.org. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sharp, Brian; Cleveland, Will (6 April 2018). "Rochester aims to recapture its rich brewery history". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "A Change in Business". Democrat and Chronicle. 2 October 1873. ProQuest 1924020586. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "United States District Couty". Democrat and Chronicle. 10 May 1877. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ a b The City of Rochester Illustrated (PDF). Rochester NY: The Post-Express Printing Company. 1890. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ The Industrial Advance of Rochester: A Historical, Statistical, and Descriptive Review. National Publishing Company. 1884. p. 100. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ "Rochester Brewing Co". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Laws of the State of New York. Albany: A. Bleecker Banks. 1878. p. 526. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Brewing in New York State Thirty-Five Years Ago". The Western Brewer. 45 (15): 10. July 15, 1915. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Skoal! Beer puts big head on city's history". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 10 November 1974. ProQuest 1936828387. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Deckert, Andrea (22 February 2013). "Pfaudler becomes piece of $20B Houston company". Rochester Business Journal. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Parker, Jenny Marsh (1884). Rochester A Story Historical. Rochester, NY: Scrantom, Wetmore and Co. p. 395. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Buying Up Breweries" (PDF). The New York Times. 15 February 1889. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Leavy, Michael; Leavy, Glenn (2004). Rochester's Dutchtown. Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 0738536857.

- ^ "From Eyesore to Opportunity: Rochester's Cataract Brewhouse – Landmark Society".

- ^ "400,000 Gallons a Day". Democrat and Chronicle. 6 August 1890. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Serious Explosion Three Men Injured by Natural Gas in a Well". Democrat and Chronicle. 26 June 1900. ProQuest 1925245184. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Stock Companies Certificates of Incorporation Filed at Albany Yesterday". Democrat and Chronicle. 27 June 1901. ProQuest 1925288490. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Illustrated Rochester, 1898-1899. Rochester Chamber of Commerce. 1899. p. 31. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ "Transfers of Union Brewery Plant to Monroe Brewing Company". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 6 September 1899. ProQuest 1924972411. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "New Real Estate Brokerage Stock Issue Austhorized". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 10 May 1927. ProQuest 1927476513. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Engines Started at New Brewery". Democrat and Chronicle. 18 December 1908. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Large Brewing Plant to Be Built With Park for Employees". Democrat and Chronicle. 7 December 1907. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "New Brewery Files Papers". Democrat and Chronicle. 25 January 1908. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Kondolf Chosen Brewery's Head". Democrat and Chronicle. 3 March 1908. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Work Well Advanced at Moerlbach Brewery". Democrat and Chronicle. 12 April 1908. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Investment in Drink Business Here $7,000,000". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Beer Making To Cease Saturday in All Plants". Democrat and Chronicle. 29 November 1918. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "To Use Part of Brewery for Making Soft Drinks". Democrat and Chronicle. 23 May 1918. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Announcing Bartholomay Quality Ice Cream". Democrat and Chronicle. 20 July 1919. p. 40. ProQuest 1926249249. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Genesee Country Bringing the Beer Home". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 13 September 1980. ProQuest 1937526069. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Rochesterians Reorganizing Brewing Firm". Democrat and Chronicle. 6 July 1932. ProQuest 1927500357. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "A Law is Modified..A Law-Abiding Rochester Institution Resumes Operation". Rochester Evening Journal. Rochester, NY. 22 March 1933. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Gillman, Gary. "Liebotschaner – of Genesee, of Liebotschan. Part I." Gary Gillman's Beer et seq. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Morrell, Alan. "Whatever Happened To ... Standard Brewery?". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ McDaniels, Skeeter (2008). Brewed in Rochester A Photographic History of Beer in Rochester, NY 1885-1975. Rochester, NY: Mountain Air Books. ISBN 9780615249414.

- ^ "Brewery Bankrupt Suds to Stop at Standard". Democrat and Chronicle (1884-2009). 9 June 1970. ProQuest 1936191816. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Finney, Michael. "N.Y. Brewery advertisement on a N.Y. made lidded beer stein". Stein Collectors International. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Morrell, Alan (21 May 2016). "Whatever Happened To ... Standard Brewery?". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

Sources

- "Rochester City Directories by Decade". Rochester Public Library. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- Rosenberg-Naparsteck, Ruth (1992). "A Brief History of Brewing in Rochester" (PDF). Rochester History. LIV (2). Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- The City of Rochester Illustrated (PDF). Rochester NY: The Post-Express Printing Company. 1890. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- One Hundred Years of Brewing A Complete History of the Progress Made in the Art, Science and Industry of Brewing in the World, Particularly During the Nineteenth Century. Chicago and New York: H.S. Rich and Co. 1903. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Clune, Henry (1988). The Genesee. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815624360.

- A History of the Brewery and Liquor Industry of Rochester, N.Y (PDF). Rochester, NY: The Kearse Publishing Company. 1907. Retrieved 22 May 2022.