History of Jamaica

The Caribbean Island of Jamaica was initially inhabited in approximately 600 AD or 650 AD by the Redware people, often associated with redware pottery.[1][2][3] By roughly 800 AD, a second wave of inhabitants occurred by the Arawak tribes, including the Tainos, prior to the arrival of Columbus in 1494.[1] Early inhabitants of Jamaica named the land "Xaymaca", meaning "land of wood and water".[4] The Spanish enslaved the Arawak, who were ravaged further by diseases that the Spanish brought with them.[5] Early historians believe that by 1602, the Arawak-speaking Taino tribes were extinct. However, some of the Taino escaped into the forested mountains of the interior, where they mixed with runaway African slaves, and survived free from first Spanish, and then English, rule.[6][7][8]

The Spanish also captured and transported hundreds of West African people to the island for the purpose of slavery. However, the majority of Africans were brought into Jamaica by the English.

In 1655, the English invaded Jamaica, and defeated the Spanish. Some African enslaved people took advantage of the political turmoil and escaped to the island's interior mountains, forming independent communities which became known as the Maroons.[9] Meanwhile, on the coast, the English built the settlement of Port Royal, a base of operations where piracy flourished as so many European rebels had been rejected from their countries to serve sentences on the seas. Captain Henry Morgan, a Welsh plantation owner and privateer, raided settlements and shipping bases from Port Royal, earning him his reputation as one of the richest pirates in the Caribbean.

In the 18th century, sugar cane replaced piracy as British Jamaica's main source of income. The sugar industry was labour-intensive and the British brought hundreds of thousands of enslaved black Africans to the island. By 1850, the black and mulatto Jamaican population outnumbered the white population by a ratio of twenty to one. Enslaved Jamaicans mounted over a dozen major uprisings during the 18th century, including Tacky's Revolt in 1760. There were also periodic skirmishes between the British and the mountain communities of the Jamaican Maroons, culminating in the First Maroon War of the 1730s and the Second Maroon War of 1795–1796.

The aftermath of the Baptist War shone a light on the conditions of slaves which contributed greatly to the abolition movement and the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which formally ended slavery in Jamaica in 1834. However, relations between the white and black community remained tense coming into the mid-19th century, with the most notable event being the Morant Bay Rebellion in 1865. The latter half of the 19th century saw economic decline, low crop prices, droughts, and disease. When sugar lost its importance, many former plantations went bankrupt, and land was sold to Jamaican peasants and cane fields were consolidated by dominant British producers.

Jamaica's first political parties emerged in the late 1920s, while workers association and trade unions emerged in the 1930s. The development of a new Constitution in 1944, universal male suffrage, and limited self-government eventually led to Jamaican Independence in 1962 with Alexander Bustamante serving as its first prime minister. The country saw an extensive period of postwar growth and a smaller reliance on the agricultural sector and a larger reliance on bauxite and mining in the 1960s and 1970s. Political power changed hands between the two dominant parties, the JLP and PNP, from the 1970s to the present day. While Jamaica's murder rate fell by nearly half after the 2010 Tivoli Incursion, the country's murder rate remains one of the highest in the world. Economic troubles hit the country in 2013, the IMF agreed to a $1 billion loan to help Jamaica meet large debt payments, making Jamaica a highly indebted country that spends around half of its annual budget on debt repayments.

Pre-Columbian Jamaica

The first inhabitants of Jamaica probably came from islands to the east in two waves of migration. About 600 CE the culture known as the “Redware people” arrived. Little is known of these people, however, beyond the red pottery they left behind.[1] Alligator Pond in Manchester Parish and Little River in St. Ann Parish are among the earliest known sites of this Ostionoid person, who lived near the coast and extensively hunted turtles and fish.[10]

Around 800 CE, the Arawak tribes of the Tainos arrived, eventually settling throughout the island. Living in villages ruled by tribal chiefs called the caciques, they sustained themselves on fishing and the cultivation of maize and cassava. At the height of their civilization, their population is estimated to have numbered as much as 60,000.[1]

The Arawak brought a South America system of raising yuca known as "conuco" to the island.[11] To add nutrients to the soil, the Arawak burned local bushes and trees and heaped the ash into large mounds, into which they then planted yuca cuttings.[11] Most Arawak lived in large circular buildings (bohios), constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. The Arawak spoke an Arawakan language and did not have writing. Some of the words used by them, such as barbacoa ("barbecue"), hamaca ("hammock"), kanoa ("canoe"), tabaco ("tobacco"), yuca, batata ("sweet potato"), and juracán ("hurricane"), have been incorporated into Spanish and English.[12]

- Cassava (yuca) roots, the Taínos' main crop

- Dujo, a wooden chair crafted by Taínos.

- Reconstruction of a Taíno village in Cuba

- Caguana Ceremonial Ball Courts Site (batey), outlined with stones in Utuado, Puerto Rico

The Spanish period (1494–1655)

Christopher Columbus is believed to be the first European to reach Jamaica. He landed on the island on 5 May 1494, during his second voyage to the Americas.[13] Columbus returned to Jamaica during his fourth voyage to the Americas. He had been sailing around the Caribbean for nearly a year when a storm beached his ships in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, on 25 June 1503. Columbus and his men remained stranded on the island for one year, finally departing on June 1504.

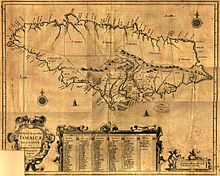

The Spanish crown granted the island to the Columbus family, but for decades it was something of a backwater, valued chiefly as a supply base for food and animal hides. In 1509 Juan de Esquivel founded the first permanent European settlement, the town of Sevilla la Nueva (New Seville), on the north coast of the island. A decade later, Friar Bartolomé de las Casas wrote to Spanish authorities about Esquivel's conduct during the Higüey massacre of 1503.[citation needed]

In 1534 the capital was moved to Villa de la Vega (later Santiago de la Vega), now called Spanish Town. This settlement served as the capital of both Spanish and English Jamaica, from its founding until 1872, after which the capital was moved to Kingston.

The Spanish enslaved many of the Arawak.[12] Some escaped to the mountains to join the Maroons.[7][8] However, most died from European diseases as well as from being overworked.[14] The Spaniards also introduced the first African slaves into the island. By the early 17th century, when most of the Taino had died out, the population of the island was about 3,000, including a small number of African slaves.[15] Disappointed in the lack of gold on the island, Jamaica was mainly used as a military base to supply colonization efforts in the mainland Americas.[16]

The Spanish colonists did not bring women in the first expeditions and took Taíno women for their common-law wives, resulting in mestizo children.[17]

Although the Taino referred to the island as "Xaymaca", the Spanish gradually changed the name to "Jamaica".[18] In the so-called Admiral's map of 1507 the island was labeled as "Jamaiqua" and in Peter Martyr's work Decades of 1511, he referred to it as both "Jamaica" and "Jamica".[18]

British rule (1655–1962)

17th century

English conquest

In late 1654, English leader Oliver Cromwell launched the Western Design armada against Spain's colonies in the Caribbean. In April 1655, General Robert Venables led the armada in an attack on Spain's fort at Santo Domingo, Hispaniola. After the Spanish repelled this poorly executed attack, the English force then sailed for Jamaica, the only Spanish West Indies island that did not have new defensive works. In May 1655, around 7,000 English soldiers landed near Jamaica's capital, named Spanish Town and soon overwhelmed the small number of Spanish troops (at the time, Jamaica's entire population only numbered around 2,500).[19]

Spain never recaptured Jamaica, losing the Battle of Ocho Rios in 1657 and the Battle of Rio Nuevo in 1658. In 1660, a group of maroons, under the leadership of Juan de Bolas, broke their alliance with the Spanish and allied themselves with the English, which served as a turning point in the English domination of the island.[20] For England, Jamaica was to be the "dagger pointed at the heart of the Spanish Empire," but in fact, it was a possession of little economic value then.[21] England gained formal possession of Jamaica from Spain in 1670 through the Treaty of Madrid. Removing the pressing need for constant defence against a Spanish attack, this change served as an incentive to planting.

British colonization

Cromwell increased the island's European population by sending indentured servants and prisoners to Jamaica. Due to Irish emigration resulting from the wars in Ireland at this time two-thirds of this 17th-century European population was Irish. But tropical diseases kept the number of Europeans under 10,000 until about 1740. Although the African slave population in the 1670s and 1680s never exceeded 10,000, by the end of the 17th century imports of slaves increased the black population to at least five times greater than the white population. Thereafter, Jamaica's African population did not increase significantly in number until well into the 18th century, in part because ships coming from the west coast of Africa preferred to unload at the islands of the Eastern Caribbean.[citation needed] At the beginning of the 18th century, the number of slaves in Jamaica did not exceed 45,000, but by 1800 it had increased to over 300,000.

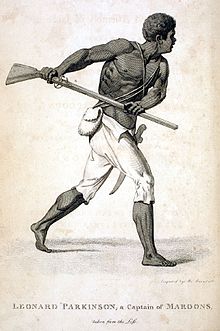

Maroons

When the English captured Jamaica in 1655, the Spanish colonists fled, leaving a large number of African slaves. These former Spanish slaves organised under the leadership of rival captains Juan de Serras and Juan de Bolas. These Jamaican Maroons intermarried with the Arawak people, and established distinct independent communities in the mountainous interior of Jamaica. They survived by subsistence farming and periodic raids of plantations. Over time, the Maroons came to control large areas of the Jamaican interior.[23]

In the second half of the seventeenth century, de Serras fought regular campaigns against English colonial forces, even attacking the capital of Spanish Town, and he was never defeated by the English. Throughout the seventeenth century, and in the first few decades of the eighteenth century, Maroon forces frequently defeated the British in small-scale skirmishes. The British colonial authorities dispatched numerous expeditions in an attempt to subdue them, but the Maroons successfully fought a guerrilla campaign against the British in the mountainous interior, and forced the British government to seek peace terms to end the expensive conflict.[24]

In the early eighteenth century, English-speaking escaped Akan slaves were at the forefront of the Maroon fighting against the British.

The House of Assembly

Beginning with the Stuart monarchy's appointment of a civil governor to Jamaica in 1661, political patterns were established that lasted well into the 20th century. The second governor, Lord Windsor, brought with him in 1662 a proclamation from the king giving Jamaica's non-slave populace the same rights as those of English citizens, including the right to make their own laws. Although he spent only ten weeks in Jamaica, Lord Windsor laid the foundations of a governing system that was to last for two centuries — a crown-appointed governor acting with the advice of a nominated council in the legislature. The legislature consisted of the governor and an elected but highly unrepresentative House of Assembly. For years, the planter-dominated Assembly was in continual conflict with the various governors and the Stuart kings; there were also contentious factions within the assembly itself. For much of the 1670s and 1680s, Charles II and James II and the assembly feuded over such matters as the purchase of slaves from ships not run by the royal English trading company. The last Stuart governor, Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle, who was more interested in treasure hunting than in planting, turned the planter oligarchy out of office. After the duke's death in 1688, the planters, who had fled Jamaica to London, succeeded in lobbying James II to order a return to the pre-Albemarle political arrangement (the local control of Jamaican planters belonging to the assembly).

Jamaica's pirates

Following the 1655 conquest, Spain repeatedly attempted to recapture Jamaica. In response, in 1657, Governor Edward D'Oyley invited the Brethren of the Coast to come to Port Royal and make it their home port. The Brethren was made up of a group of pirates who were descendants of cattle-hunting boucaniers (later Anglicised to buccaneers), who had turned to piracy after being robbed by the Spanish (and subsequently thrown out of Hispaniola).[25] These pirates concentrated their attacks on Spanish shipping, whose interests were considered the major threat to the town. These pirates later became legal English privateers who were given letters of marque by Jamaica's governor. Around the same time that pirates were invited to Port Royal, England launched a series of attacks against Spanish shipping vessels and coastal towns. By sending the newly appointed privateers after Spanish ships and settlements, England had successfully set up a system of defense for Port Royal.[25] Jamaica became a haven of privateers, buccaneers, and occasionally outright pirates: Christopher Myngs, Edward Mansvelt, and most famously, Henry Morgan.

England gained formal possession of Jamaica from Spain in 1670 through the Treaty of Madrid. Removing the pressing need for constant defense against a Spanish attack, this change served as an incentive to planting. This settlement also improved the supply of slaves and resulted in more protection, including military support, for the planters against foreign competition. As a result, the sugar monoculture and slave-worked plantation society spread across Jamaica throughout the 18th century, decreasing Jamaica's dependence on privateers for protection and funds.

However, the English colonial authorities continued to have difficulties suppressing the Spanish Maroons, who made their homes in the mountainous interior and mounted periodic raids on estates and towns, such as Spanish Town. The Karmahaly Maroons, led by Juan de Serras, continued to stay in the forested mountains, and periodically fought the English. In the 1670s and 1680s, in his capacity as an owner of a large slave plantation, Morgan led three campaigns against the Jamaican Maroons of Juan de Serras. Morgan achieved some success against the Maroons, who withdrew further into the Blue Mountains, where they were able to stay out of the reach of Morgan and his forces.[26]

Another blow to Jamaica's partnership with privateers was the violent earthquake which destroyed much of Port Royal on 7 June 1692. Two-thirds of the town sank into the sea immediately after the main shock.[27] After the earthquake, the town was partially rebuilt but the colonial government was relocated to Spanish Town, which had been the capital under Spanish rule. Port Royal was further devastated by a fire in 1703 and a hurricane in 1722. Most of the sea trade moved to Kingston. By the late 18th century, Port Royal was largely abandoned.[28]

18th century

Jamaica's sugar boom

In the mid-17th century, sugarcane was introduced to the British West Indies by the Dutch,[29][30] from Brazil. Upon landing in Jamaica and other islands, they quickly urged local growers to change their main crops from cotton and tobacco to sugarcane. With depressed prices of cotton and tobacco, due mainly to stiff competition from the North American colonies, the farmers switched, leading to a boom in the Caribbean economies. Sugarcane was quickly snapped up by the British, who used it in cakes and to sweeten tea. In the 18th century, sugar replaced piracy as Jamaica's main source of income. The sugar industry was labor-intensive and the British brought hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans to Jamaica. By 1832, the median-size plantation in Jamaica had about 150 slaves, and nearly one of every four bondsmen lived on units that had at least 250 slaves.[31] In The Book of Night Women, author Marlon James indicates that the ratio of slave owners to enslaved Africans is 1:33.[citation needed] James also depicts atrocities that slave owners subjected slaves to along with violent resistance from the slaves as well as numerous slaves who died in pursuit of freedom. After slavery was abolished in 1834, sugarcane plantations used a variety of forms of labour including workers imported from India under contracts of indenture.

The 18th century saw thousands of slaves imported into Jamaica into the now profitable sugar plantations. From 1740 to 1834, the estimated slave population continued to grow, reaching into the three hundred thousands by the end of the century.[32] The sugar boom of Jamaica would change the dynamics of the slave market and the economics of the West Indies. Towards the end of the 18th century, Jamaica became the leader of sugar production for the British empire, producing up to 66% of the empire's sugar in 1796.[32] The price of sugar would rise tremendously as the market for sugar in Great Britain was large, especially with the rich. From 1748 to 1755, the value of sugar exportations from Jamaica increased by nearly three times, going from £688,000 to £1,618,000 over the period.[32] With the high demand for sugar out of Jamaica, the demand for slaves increased, leading to an increase in prices for slaves. From 1750 to 1807, the average price for a slave in the Caribbean would continue to steadily rise, reaching a high of £73 in 1805.[32] Prices soared towards the dawn of the new century as a result of the plantation system in Saint-Domingue falling due to the Haitian revolution, putting more emphasis on Jamaica. Interestingly, the most efficient plantations employed fewer slaves per acre of land, which was observed in St. Andrews parish.[33] This created a higher demand for slaves that were efficient and in good health and shape, inflating the prices of those individuals and creating a quality over quantity dynamic. Internal markets would also develop, namely in Kingston, that allowed for plantations to reallocate labor and to disuade or break-up bonds and families made by slaves.[34]

With an increase in traffic of ships, sugar, and slaves, British merchants implemented the guarantee system, in which a merchant would be appointed to guarantee payment upon the delivery of the enslaved.[35] This system served as a safety net for merchants as they had no influence over the price of the enslaved sold as age, weight, and vitality effected price range. With a safe system of commerce and the rising prices of sugar, the opportunity to make riches presented itself and attracted thousands of merchants and sailors looking to gain riches. Most of the slaves and their sales would be run through middlemen known as "Guinea Factors" who served as "the indispensable nexus between the transatlantic slave trade and the plantation complex," according to Radburn.[36] These factors were instrumental in keeping the slave trade and economy running smoothly, as everything went in and out through them. Records of some of the factors and how many slaves they sold show just how much their work perpetuated the slave economy. From 1785 to 1796, five factors sold 78,258 slaves combined, with a Alexandre Lindo accounting for 25,706 of them a 17% share of the entire Jamaican slave trade.[36] Such a large amount of slaves sold by one man in a little over ten years shows just how popular and profitable the slave market had become.

First Maroon War

Starting in the late seventeenth century, there were periodic skirmishes between the English colonial militia and the Windward Maroons, alongside occasional slave revolts. In 1673 one such revolt in St. Ann's Parish of 200 slaves created the separate group of Leeward Maroons. These Maroons united with a group of Madagascars who had survived the shipwreck of a slave ship and formed their own maroon community in St. George's parish. Several more rebellions strengthened the numbers of this Leeward group. Notably, in 1690 a revolt at Sutton's plantation in Clarendon Parish of 400 slaves considerably strengthened the Leeward Maroons.[37] The Leeward Maroons inhabited "cockpits," caves, or deep ravines that were easily defended, even against troops with superior firepower. Such guerrilla warfare and the use of scouts who blew the abeng (the cow horn, which was used as a trumpet) to warn of approaching enemies allowed the Maroons to evade, thwart, frustrate, and defeat the British.[citation needed]

Early in the 18th century, the Maroons took a heavy toll on British colonial militiamen who sent against them in the interior, in what came to be known as the First Maroon War. In 1728, the British authorities sent Robert Hunter to assume the office of governor of Jamaica; Hunter's arrival led to an intensification of the conflict. However, despite increased numbers, the British colonial authorities were unable to defeat the Windward Maroons.[38]

In 1739–40, the British government in Jamaica recognised that it could not defeat the Maroons, so they offered them treaties of peace instead. In 1739, the British, led by Governor Edward Trelawny, sued for peace with the Leeward Maroon leader, Cudjoe, described by British planters as a short, almost dwarf-like man who for years fought skilfully and bravely to maintain his people's independence. Some writers maintain that during the conflict, Cudjoe became increasingly disillusioned, and quarrelled with his lieutenants and with other Maroon groups. He felt that the only hope for the future was a peace treaty with the enemy which recognized the independence of the Leeward Maroons. In 1742, Cudjoe had to suppress a rebellion of Leeward Maroons against the treaty.[39]

The First Maroon War came to an end with a 1739–1740 agreement between the Maroons and the British government. In exchange, they were asked to agree not to harbour new runaway slaves, but rather to help catch them. This last clause in the treaty naturally caused a split between the Maroons and the mainly mulatto population, although from time to time runaways from the plantations still found their way into maroon settlements, such as those led by Three Fingered Jack (Jamaica). Another provision of the agreement was that the Maroons would serve to protect the island from invaders. The latter was because the Maroons were revered by the British as skilled warriors.

A year later, the even more rebellious Windward Maroons led by Quao also agreed to sign a treaty under pressure from both white Jamaican militias and the Leeward Maroons. Eventually, Queen Nanny agreed to a land patent which meant that her Maroons also accepted peace terms.

The Maroons were to remain in their five main towns (Accompong; Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town); Nanny Town, later known as Moore Town; Scott's Hall (Jamaica); and Charles Town, Jamaica), living under their own rulers and a British supervisor.

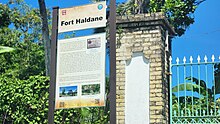

Tacky's revolt

In May 1760, Tacky, a slave overseer on the Frontier plantation in Saint Mary Parish, led a group of enslaved Africans in taking over the Frontier and Trinity plantations while killing their enslavers. They then marched to the storeroom at Fort Haldane, where the munitions to defend the town of Port Maria were kept. After killing the storekeeper, Tacky and his men stole nearly 4 barrels of gunpowder and 40 firearms with shot, before marching on to overrun the plantations at Heywood Hall and Esher.[40]

By dawn, hundreds of other slaves had joined Tacky and his followers. At Ballard's Valley, the rebels stopped to rejoice in their success. One slave from Esher decided to slip away and sound the alarm.[40] Obeahmen (Caribbean witch doctors) quickly circulated around the camp dispensing a powder that they claimed would protect the men from injury in battle and loudly proclaimed that an Obeahman could not be killed. The confidence was high.[40] Soon there were 70 to 80 mounted militia on their way along with some Maroons from Scott's Hall, who were bound by treaty to suppress such rebellions. When the militia learned of the Obeahman's boast of not being able to be killed, an Obeahman was captured, killed, and hung with his mask, ornaments of teeth and bone and feather trimmings at a prominent place visible from the encampment of rebels. Many of the rebels, confidence shaken, returned to their plantations. Tacky and 25 or so men decided to fight on.[40] Tacky and his men went running through the woods being chased by the Maroons and their legendary marksman, Davy the Maroon.

While running at full speed, Davy shot Tacky and cut off his head as evidence of his feat, for which he would be richly rewarded. Tacky's head was later displayed on a pole in Spanish Town until a follower took it down in the middle of the night. The rest of Tacky's men were found in a cave near Tacky Falls, having committed suicide rather than going back to slavery.[40]

Second Maroon War

In 1795, the Second Maroon War was instigated when two Maroons were flogged by a black slave for allegedly stealing two pigs. When six Maroon leaders came to the British to present their grievances, the British took them as prisoners. This sparked an eight-month conflict, spurred by the fact that Maroons felt that they were being mistreated under the terms of Cudjoe's Treaty of 1739, which ended the First Maroon War. The war lasted for five months as a bloody stalemate. The British colonial authorities could muster 5,000 men, outnumbering the Maroons ten to one, but the mountainous and forested topography of Jamaica proved ideal for guerrilla warfare. The Maroons surrendered in December 1795. A treaty signed in December between Major General George Walpole and the Maroon leaders established that the Maroons would beg on their knees for the King's forgiveness, return all runaway slaves, and be relocated elsewhere in Jamaica. The governor of Jamaica ratified the treaty but gave the Maroons only three days to present themselves to beg forgiveness on 1 January 1796. Suspicious of British intentions, most of the Maroons did not surrender until mid-March. The British used the contrived breach of the treaty as a pretext to deport the entire Trelawny Town Maroons to Nova Scotia. After a few years, the Maroons were again deported to the new British settlement of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

19th century

Slave resistance

Hundreds of runaway slaves secured their freedom by escaping and fighting alongside the Maroons of Trelawny Town. About half of these runaways surrendered with the Maroons, and many were executed or re-sold in slavery to Cuba. However, a few hundred stayed out in the forests of the Cockpit Country, and they joined other runaway communities. In 1798, a slave named Cuffee ran away from a western estate, and established a runaway community which was able to resist attempts by the colonial forces and the Maroons remaining in Jamaica to subdue them.[41] In the early nineteenth century, colonial records describe hundreds of runaway slaves escaping to "Healthshire" where they flourished for several years before they were captured by a party of Maroons.[42]

In 1812, a community of runaways started when a dozen men and some women escaped from the sugar plantations of Trelawny into the Cockpit Country, and they created a village with the curious name of Me-no-Sen-You-no-Come. By the 1820s, Me-no-Sen-You-no-Come housed between 50 and 60 runaways. The headmen of the community were escaped slaves named Warren and Forbes. Me-no-Sen-You-no-Come also conducted a thriving trade with slaves from the north coast, who exchanged their salt provisions with the runaways for their ground provisions.[43] In October 1824, the colonial militias tried to destroy this community. However, the community of Me-no-Sen-You-no-Come continued to thrive in the Cockpit Country until Emancipation in the 1830s.[44]

The Baptist War

In 1831, enslaved Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe led a strike among demanding more freedom and a working wage of "half the going wage rate." Upon refusal of their demands, the strike escalated into a full rebellion, in part because Sharpe had also made military preparations with a rebel military group known as the Black Regiment led by a slave known as Colonel Johnson of Retrieve Estate, about 150 strong with 50 guns among them. Colonel Johnson's Black Regiment clashed with a local militia led by Colonel Grignon at old Montpelier on December 28. The militia retreated to Montego Bay while the Black Regiment advanced an invasion of estates in the hills, inviting more slaves to join while burning houses, fields, and other properties, setting off a trail of fires through the Great River Valley in Westmoreland and St. Elizabeth to St James.[45]

The Baptist War, as it was known, became the largest slave uprising in the British West Indies,[46] lasting 10 days and mobilised as many as 60,000 of Jamaica's 300,000 slaves.[47] The rebellion was suppressed by colonial forces under the control of Sir Willoughby Cotton.[48] The reaction of the Jamaican Government and plantocracy[49] was far more brutal. Approximately five hundred slaves were killed in total: 207 during the revolt and somewhere in the range between 310 and 340 slaves were killed through "various forms of judicial executions" after the rebellion was concluded, at times, for quite minor offenses (one recorded execution indicates the crime being the theft of a pig; another, a cow).[50] An 1853 account by Henry Bleby described how three or four simultaneous executions were commonly observed; bodies would be allowed to pile up until workhouse slaves carted the bodies away at night and buried them in mass graves outside town.[46] The brutality of the plantocracy during the revolt is thought to have accelerated the process of emancipation, with initial measures beginning in 1833.

Emancipation

The British Parliament held two inquires as a result of the loss of property and life in the 1831 Baptist War rebellion.[citation needed] Their reports of the conditions of the slaves contributed greatly to the abolition movement and helped lead to the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, formally ending slavery in Jamaica on August 1, 1834. However, the act stipulated that all slaves above the age of 6 on the date abolition took effect, were bound (indentured) in service to their former owners', albeit with a guarantee of rights, under what was called the "Apprenticeship System". The length of servitude that was required varied based on the former slaves’ responsibilities with "domestic slaves" owing four years of service and "agriculture slaves" owing six. In addition to the apprentice system, former slave owners were to be compensated for the loss of their "property." By 1839, "Twenty Million Pounds Sterling" was paid out to the owners of slaves freed in the Caribbean and Africa under the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, half of whom were absentee landlords residing in Great Britain.

The apprentice system was unpopular amongst Jamaica's "former" slaves — especially elderly slaves — who unlike slave owners were not provided any compensation. This led to protests. In the face of mounting pressure, a resolution was passed on August 1, 1838, releasing all "apprentices" regardless of position from all obligations to their former masters.

With the abolition of the slave trade in 1808 and slavery itself in 1834, the island's sugar- and slave-based economy faltered. The period after emancipation in 1834 initially was marked by a conflict between the plantocracy and elements in the Colonial Office over the extent to which individual freedom should be coupled with political participation for blacks. In 1840 the assembly changed the voting qualifications in a way that enabled a majority of blacks and people of mixed race (browns or mulattos) to vote. But neither change in the political system, nor abolition of slavery, changed the planter's chief interest — which lay in the continued profitability of their estates — and they continued to dominate the elitist assembly. Nevertheless, at the end of the 19th century and in the early years of the 20th century, the Crown began to allow some Jamaicans – mostly local merchants, urban professionals, and artisans—to hold seats on appointed councils.

Rumblings of emancipation movements had begun as early as the 1780s which scared many planters. With the fear of being unable to purchase a sufficient labor force through the slave trade, the value of women increased. From 1788 to 1807, some planters began to buy women at a higher rate, trying to balance the gender ratio to 50-50.[51] The reason for buying women in higher amounts was so that they could give birth to more slaves. This served two purposes, one was to supply their labor force even in the eventual passing of emancipation, and secondly to cut down on future spending by instead having your slave be born instead of purchased. Minimizing spending became a large priority following emancipation and the decline of the sugar based economy of Jamaica, making running a plantation very expensive. Merchants still found a way to stay wealthy in the wake of emancipation through the importation of British goods into Spanish America, enabling communities such as Kingston that were built on the economy of the slave trade to see continued economic prosperity.[52]

The Morant Bay Rebellion

Tensions between blacks and whites resulted in the October 1865 Morant Bay rebellion led by Paul Bogle. The rebellion was sparked on 7 October, when a black man was put on trial and imprisoned for allegedly trespassing on a long-abandoned plantation. During the proceedings, James Geoghegon, a black spectator, disrupted the trial, and in the police's attempts to seize him to remove him from the courthouse, a fight broke out between the police and other spectators. While pursuing Geoghegon, two policemen were beaten with sticks and stones.[53] The following Monday, arrest warrants were issued for several men for rioting, resisting arrest, and assaulting the police. Among them was Baptist preacher Paul Bogle. A few days later on 11 October, Mr. Paul Bogle marched with a group of protesters to Morant Bay. When the group arrived at the courthouse they were met by a small and inexperienced volunteer militia. The crowd began pelting the militia with rocks and sticks, and the militia opened fire on the group, killing seven black protesters before retreating.

Governor John Eyre sent government troops, under Brigadier-General Alexander Nelson,[54] to hunt down the poorly armed rebels and bring Paul Bogle back to Morant Bay for trial. The troops met with no organized resistance, yet they killed blacks indiscriminately, most of whom had not been involved in the riot or rebellion. According to one soldier, "We slaughtered all before us... man or woman or child.”[citation needed] In the end, 439 black Jamaicans were killed directly by soldiers, and 354 more (including Paul Bogle) were arrested and later executed, some without proper trials. Paul Bogle was executed "either the same evening he was tried or the next morning."[55] Other punishments included the flogging of over 600 men and women (including some pregnant women), and long prison sentences. Thousands of homes belonging to black Jamaicans were burned down without any justifiable reason.

George William Gordon, Jamaican-born plantation owner, businessman and politician, who was the mixed-race son of Scottish-born plantation owner of Cherry Gardens in St. Andrew, Joseph Gordon, and his black enslaved mistress. Gordon, had been critical of Governor John Eyre and his policies, and was later arrested by the Governor who believed he had been behind the rebellion. Despite having very little to do with the rebellion, Gordon was eventually executed. Though he was arrested in Kingston, he was transferred by Eyre to Morant Bay, where he could be tried under martial law. The execution and trial of Gordon via martial law raised some constitutional issues back in Britain, where concerns emerged about whether British dependencies should be ruled under the government of law, or through a military license.[56] Gordon hanged on 23 October, after a speedy trial — just two days after his trial had begun. He and William Bogle, Paul's brother, "were both tried together, and executed at the same time.”[citation needed]

Decline of the sugar industry

During most of the 18th century, the monocrop economy based on sugarcane production for export flourished. In the last quarter of the century, however, the Jamaican sugar economy declined as famines, hurricanes, colonial wars, and wars of independence disrupted trade. By the 1820s, Jamaican sugar became less competitive with the high-volume producers like Cuba, and production subsequently declined. By 1882 sugar output was less than half what it was in 1828. A major reason for the decline was the British Parliament's 1807 abolition of the slave trade, under which the transportation of slaves to Jamaica after 1 March 1808 was forbidden. The abolition of the slave trade was followed by the abolition of slavery in 1834 and full emancipation of slaves within four years. Unable to convert the ex-slaves into a sharecropping tenant class similar to the one established in the post-Civil War South of the United States, planters became increasingly dependent on wage labour and began recruiting workers abroad, primarily from India, China, and Sierra Leone. Many of the former slaves settled in peasant or small farm communities in the interior of the island like the "yam belt," where they engaged in subsistence and some cash crop farming.

The second half of the 19th century was a period of severe economic decline for Jamaica. Low crop prices, droughts, and disease led to serious social unrest, culminating in the Morant Bay rebellions of 1865. However, renewed British administration after the 1865 rebellion, in the form of crown colony status, resulted in some social and economic progress as well as investment in the physical infrastructure. Agricultural development was the centrepiece of restored British rule in Jamaica. In 1868 the first large-scale irrigation project was launched. In 1895 the Jamaica Agricultural Society was founded to promote more scientific and profitable methods of farming. Also in the 1890s, the Crown Lands Settlement Scheme was introduced, a land reform program of sorts, which allowed small farmers to purchase two hectares or more of land on favorable terms.

Between 1865 and 1930, the character of landholding in Jamaica changed substantially, as sugar declined in importance. As many former plantations went bankrupt, some land was sold to Jamaican peasants under the Crown Lands Settlement whereas other cane fields were consolidated by dominant British producers, most notably by the British firm Tate and Lyle. Although the concentration of land and wealth in Jamaica was not as drastic as in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, by the 1920s the typical sugar plantation on the island had increased to an average of 266 hectares. But, as noted, smallscale agriculture in Jamaica survived the consolidation of land by sugar powers. The number of small holdings in fact tripled between 1865 and 1930, thus retaining a large portion of the population as peasantry. Most of the expansion in small holdings took place before 1910, with farms averaging between two and twenty hectares.

The rise of the banana trade during the second half of the 19th century also changed production and trade patterns on the island. Bananas were first exported in 1867, and banana farming grew rapidly thereafter. By 1890, bananas had replaced sugar as Jamaica's principal export. Production rose from 5 million stems (32 percent of exports) in 1897 to an average of 20 million stems a year in the 1920s and 1930s, or over half of domestic exports. As with sugar, the presence of American companies, like the well-known United Fruit Company in Jamaica, was a driving force behind renewed agricultural exports. Competition was introduced by the Jamaican-Italian firm Lanasa & Goffe raising the price paid for bananas in 1906. The British also became more interested in Jamaican bananas than in the country's sugar. Expansion of banana production, however, was hampered by serious labour shortages. The rise of the banana economy took place amidst a general exodus of up to 11,000 Jamaicans a year.

Coffee plantations also suffered as a result of emancipation. Even with paid labor becoming a fixture on these coffee plantations, the newfound wages that ex-slaves were paid and lower profits made it difficult to effectively run the plantation financially. One planter found that running his plantation cost about £2400 per year, which was about double of what it had cost in the years before 1839.[57] Some planters attempted to tie the now free laborers to the land by making them have to pay rent if they worked and lived on the plantation. Many laborers of course rejected these arrangements, as with a declining plantation economy they sought to separate themselves from the plantation.[57] Following these trends, the market for many of these workers declined on the plantation and shifted to the more urban centers such as Kingston, leaving the plantation economy of Jamaica behind.

Jamaica as a Crown Colony

In 1846 Jamaican planters — adversely affected by the loss of slave labour — suffered a crushing blow when Britain passed the Sugar Duties Act, eliminating Jamaica's traditionally favoured status as its primary supplier of sugar. The Jamaica House of Assembly stumbled from one crisis to another until the collapse of the sugar trade, when racial and religious tensions came to a head during the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865. Although suppressed ruthlessly, the severe rioting so alarmed the planters that the two-centuries-old assembly voted to abolish itself and asked for the establishment of direct British rule. In 1866 the new governor John Peter Grant arrived to implement a series of reforms that accompanied the transition to a crown colony. The government consisted of the Legislative Council and the executive Privy Council containing members of both chambers of the House of Assembly, but the Colonial Office exercised effective power through a presiding British governor. The council included a few handpicked prominent Jamaicans for the sake of appearance only.[citation needed] In the late 19th century, crown colony rule was modified; representation and limited self-rule were reintroduced gradually into Jamaica after 1884. The colony's legal structure was reformed along the lines of English common law and county courts, and a constabulary force was established. The smooth working of the crown colony system depended on a good understanding and an identity of interests between the governing officials, who were British, and most of the nonofficial, nominated members of the Legislative Council, who were Jamaicans. The elected members of this body were in a permanent minority and without any influence or administrative power. The unstated alliance – based on shared color, attitudes, and interest – between the British officials and the Jamaican upper class was reinforced in London, where the West India Committee lobbied for Jamaican interests. Jamaica's white or near-white propertied class continued to hold the dominant position in every respect; the vast majority of the black population remained poor and disenfranchised.

Religion

Until it was disestablished in 1870, the Church of England in Jamaica was the established church. It represented the white English community. It received funding from the colonial government and was given responsibility for providing religious instruction to the slaves. It was challenged by Methodist missionaries from England, and the Methodists in turn were denounced as troublemakers. The Church of England in Jamaica established the Jamaica Home and Foreign Missionary Society in 1861; its mission stations multiplied, with financial help from religious organizations in London. The Society sent its own missionaries to West Africa. Baptist missions grew rapidly, thanks to missionaries from England and the United States, and became the largest denomination by 1900. Baptist missionaries denounced the apprentice system as a form of slavery. In the 1870s and 1880s, the Methodists opened a high school and a theological college. Other Protestant groups included the Moravians, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Seventh-day Adventist, Church of God, and others. There were several thousand Roman Catholics.[58] The population was largely Christian by 1900, and most families were linked with the church or a Sunday School. Traditional pagan practices persisted in an unorganized fashion, such as witchcraft.[59]

Kingston, the new capital

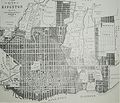

In 1872, the government passed an act to transfer government offices from Spanish Town to Kingston. Kingston had been founded as a refuge for survivors of the 1692 earthquake that destroyed Port Royal. The town did not begin to grow until after the further destruction of Port Royal by fire in 1703. Surveyor John Goffe drew up a plan for the town based on a grid bounded by North, East, West, and Harbour Streets. By 1716 it had become the largest town and the center of trade for Jamaica. The government sold the land to people with the regulation that they purchase no more than the amount of the land that they owned in Port Royal, and the only land on the sea front. Gradually wealthy merchants began to move their residences from above their businesses to the farm lands north on the plains of Liguanea. In 1755 the governor, Sir Charles Knowles, had decided to transfer the government offices from Spanish Town to Kingston. It was thought by some to be an unsuitable location for the Assembly in proximity to the moral distractions of Kingston, and the next governor rescinded the Act. However, by 1780 the population of Kingston was 11,000, and the merchants began lobbying for the administrative capital to be transferred from Spanish Town, which was by then eclipsed by the commercial activity in Kingston. The 1907 Kingston earthquake destroyed much of the city. Considered by many writers of that time one of the world's deadliest earthquakes, it resulted in the death of over 800 Jamaicans and destroyed the homes of over 10,000 more.[60]

- Kingston in 1891

- Horse-drawn carriages in Kingston, 1891

- Map of Kingston in 1897

- View of Kingston in 1907 showing damage caused by the earthquake.

Early 20th century

Bananas

The earliest modern plantations originated in Jamaica and the related Western Caribbean Zone, including most of Central America. It involved the combination of modern transportation networks of steamships and railroads with the development of refrigeration that allowed more time between harvesting and ripening. North American shippers like Lorenzo Dow Baker and Andrew Preston, the founders of the Boston Fruit Company started this process in the 1870s, but railroad builders like Minor C. Keith also participated, eventually culminating in the multi-national giant corporations like today's Chiquita Brands International and Dole. These companies were monopolistic, vertically integrated (meaning they controlled growing, processing, shipping and marketing) and usually used political manipulation to build enclave economies (economies that were internally self-sufficient, virtually tax exempt, and export-oriented that contribute very little to the host economy). Alfred Constantine Goffe was a Jamaican Businessman whose St. Mary Banana co-op was the first in Jamaica, opposed the larger export companies and by 1909 had the largest Jamaican owned Banana export company.[61] The resurgence of the Baltimore docks and newer, faster boats, refrigeration on board steamships and rail-cars enabled bananas to travel further to meet the demand for the yellow fruit, for which the firm of Lanasa and Goffe excelled .

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, a black activist, Trade Unionist, and husband to Amy Jacques Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League in 1914, one of Jamaica's first political parties in 1929, and a workers association in the early 1930s. Garvey also promoted the Back-to-Africa movement, which called for those of African descent to return to the homelands of their ancestors.[62] Garvey, a controversial figure, had been the target of a four-year investigation by the United States government. He was convicted of mail fraud in 1923 and had served most of a five-year term in an Atlanta penitentiary when he was deported to Jamaica in 1927. Garvey left the colony in 1935 to live in the United Kingdom, where he died heavily in debt five years later. He was proclaimed Jamaica's first national hero in the 1960s after Edward P.G. Seaga, then a government minister arranged the return of his remains to Jamaica. In 1987 Jamaica petitioned the United States Congress to pardon Garvey on the basis that the federal charges brought against him were unsubstantiated and unjust.[63]

Rastafari movement

The Rastafari movement, a new religion, emerged among impoverished and socially disenfranchised Afro-Jamaican communities in 1930s Jamaica. Its Afrocentric ideology was largely a reaction against Jamaica's then-dominant British colonial culture. It was influenced by both Ethiopianism and the Back-to-Africa movement promoted by black nationalist figures like Marcus Garvey. The movement developed after several Christian clergymen, most notably Leonard Howell, proclaimed that the crowning of Haile Selassie as Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930 fulfilled a Biblical prophecy. By the 1950s, Rastafari's counter-cultural stance had brought the movement into conflict with wider Jamaican society, including violent clashes with law enforcement. In the 1960s and 1970s, it gained increased respectability within Jamaica and greater visibility abroad through the popularity of Rasta-inspired reggae musicians like Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Enthusiasm for Rastafari declined in the 1980s, following the deaths of Haile Selassie and Marley.[64]

The Great Depression and worker protests

The Great Depression caused sugar prices to slump in 1929 and led to the return of many Jamaicans. Economic stagnation, discontent with unemployment, low wages, high prices, and poor living conditions caused social unrest in the 1930s. Uprisings in Jamaica began on the Frome Sugar Estate in the western parish of Westmoreland and quickly spread east to Kingston. Jamaica, in particular, set the pace for the region in its demands for economic development from British colonial rule.

Because of disturbances in Jamaica and the rest of the region, the British in 1938 appointed the Moyne Commission. An immediate result of the commission was the Colonial Development Welfare Act, which provided for the expenditure of approximately Ł1 million a year for twenty years on coordinated development in the British West Indies. Concrete actions, however, were not implemented to deal with Jamaica's massive structural problems.

New unions and parties

The rise of nationalism, as distinct from island identification or desire for self-determination, is generally dated to the 1938 labor riots that affected both Jamaica and the islands of the Eastern Caribbean. William Alexander Bustamante (formerly William Alexander Clarke), a moneylender in the capital city of Kingston who had formed the Jamaica Trade Workers and Tradesmen Union (JTWTU) three years earlier, captured the imagination of the black masses with his messianic personality, even though he himself was light-skinned, affluent, and aristocratic. Bustamante emerged from the 1938 strikes and other disturbances as a populist leader and the principal spokesperson for the militant urban working class, and in that year, using the JTWTU as a stepping stone, he founded the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union (BITU), which inaugurated Jamaica's worker's movement.

A first cousin of Bustamante, Norman W. Manley, concluded as a result of the 1938 riots that the real basis for national unity in Jamaica lay in the masses. Unlike the union-oriented Bustamante, however, Manley was more interested in access to control over state power and political rights for the masses. On 18 September 1938, he inaugurated the People's National Party (PNP), which had begun as a nationalist movement supported by Bustamante and the mixed-race middle class (which included the intelligentsia) and the liberal sector of the business community with leaders who were highly educated members of the upper middle class. The 1938 riots spurred the PNP to unionize labor, although it would be several years before the PNP formed major labor unions. The party concentrated its earliest efforts on establishing a network both in urban areas and in banana-growing rural parishes, later working on building support among small farmers and in areas of bauxite mining.

The PNP adopted a socialist ideology in 1940 and later joined the Socialist International, allying itself formally with the social democratic parties of Western Europe. Guided by socialist principles, Manley was not a doctrinaire socialist. PNP socialism during the 1940s was similar to British Labour Party ideas on state control of the factors of production, equality of opportunity, and a welfare state, although a left-wing element in the PNP held more orthodox Marxist views and worked for the internationalization of the trade union movement through the Caribbean Labour Congress. In those formative years of Jamaican political and union activity, relations between Manley and Bustamante were cordial. Manley defended Bustamante in court against charges brought by the British for his labor activism in the 1938 riots and looked after the BITU during Bustamante's imprisonment.

Bustamante had political ambitions of his own, however. In 1942, while still incarcerated, he founded a political party to rival the PNP, called the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP). The new party, whose leaders were of a lower class than those of the PNP, was supported by conservative businessmen and 60,000 dues-paying BITU members, who encompassed dock and sugar plantation workers and other unskilled urban laborers. On his release in 1943, Bustamante began building up the JLP. Meanwhile, several PNP leaders organized the leftist-oriented Trade Union Congress (TUC). Thus, from an early stage in modern Jamaica, unionized labor was an integral part of organized political life.

For the next quarter-century, Bustamante and Manley competed for center stage in Jamaican political affairs, the former espousing the cause of the "barefoot man"; the latter, "democratic socialism," a loosely defined political and economic theory aimed at achieving a classless system of government. Jamaica's two founding fathers projected quite different popular images. Bustamante, lacking even a high school diploma, was an autocratic, charismatic, and highly adept politician; Manley was an athletic, Oxford-trained lawyer, Rhodes scholar, humanist, and liberal intellectual. Although considerably more reserved than Bustamante, Manley was well-liked and widely respected. He was also a visionary nationalist who became the driving force behind the crown colony's quest for independence.

Following the 1938 disturbances in the West Indies, London sent the Moyne Commission to study conditions in the British Caribbean territories. Its findings led in the early 1940s to better wages and a new constitution. Issued on 20 November 1944, the Constitution modified the crown colony system and inaugurated limited self-government based on the Westminster model of government and universal adult suffrage. It also embodied the island's principles of ministerial responsibility and the rule of law. Thirty-one percent of the population participated in the 1944 elections. The JLP – helped by its promises to create jobs, its practice of dispensing public funds in pro-JLP parishes, and the PNP's relatively radical platform – won an 18 percent majority of the votes over the PNP, as well as 22 seats in the 32-member House of Representatives, with 5 going to the PNP and 5 to other short-lived parties. In 1945 Bustamante took office as Jamaica's first premier (the pre-independence title for head of government).

Under the new charter, the British governor, assisted by the six-member Privy Council and 10-member Executive Council, remained responsible solely to the crown. The Jamaican Legislative Council became the upper house, or Senate, of the bicameral Parliament. House members were elected by adult suffrage from single-member electoral districts called constituencies. Despite these changes, ultimate power remained concentrated in the hands of the governor and other high officials.[65][66]

Independent Jamaica (1962–present)

1960s

The road to independence

After World War II, Jamaica began a relatively long transition to full political independence. Jamaicans preferred British culture over American, but they had a tumultuous relationship with the British and resented British domination, racism, and the dictatorial Colonial Office. Britain gradually granted the colony more self-government under periodic constitutional changes. Jamaica's political patterns and governmental structure were shaped during two decades of what was called "constitutional decolonisation," the period between 1944 and independence in 1962.

Having seen how little popular appeal the PNP's 1944 campaign position had, the party shifted toward the centre in 1949 and remained there until 1974. The PNP actually won a 0.8-percent majority of the votes over the JLP in the 1949 election, but the JLP won a majority of the House seats. In the 1950s, the PNP and JLP became increasingly similar in their sociological composition and ideological outlook. During the Cold War years, socialism became an explosive domestic issue. The JLP exploited it among property owners and churchgoers, attracting more middle-class support. As a result, PNP leaders diluted their socialist rhetoric, and in 1952 the PNP moderated its image by expelling four prominent leftists who had controlled the TUC. The PNP then formed the more conservative National Workers Union (NWU). Henceforth, PNP socialism meant little more than national planning within a framework of private property and foreign capital. The PNP retained, however, a basic commitment to socialist precepts, such as public control of resources and more equitable income distribution. Manley's PNP came to the office for the first time after winning the 1955 elections with an 11-percent majority over the JLP and 50.5 percent of the popular vote.

Amendments to the constitution that took effect in May 1953 reconstituted the Executive Council and provided for eight ministers to be selected from among House members. The first ministries were subsequently established. These amendments also enlarged the limited powers of the House of Representatives and made elected members of the governor's executive council responsible to the legislature. Manley, elected chief minister beginning in January 1955, accelerated the process of decolonisation during his able stewardship. Further progress toward self-government was achieved under constitutional amendments in 1955 and 1956, and cabinet government was established on 11 November 1957.

Assured by British declarations that independence would be granted to a collective West Indian state rather than to individual colonies, Manley supported Jamaica's joining nine other British territories in the West Indies Federation, established on 3 January 1958. Manley became the island's premier after the PNP again won a decisive victory in the general election in July 1959, securing 30 out of 45 House seats.

Membership in the federation remained an issue in Jamaican politics. Bustamante, reversing his previously supportive position on the issue, warned of the financial implications of membership – Jamaica was responsible for 43 percent of its own financing – and inequity in Jamaica's proportional representation in the federation's House of Assembly. Manley's PNP favoured staying in the federation, but he agreed to hold a referendum in September 1961 to decide on the issue. When 54 percent of the electorate voted to withdraw, Jamaica left the federation, which dissolved in 1962 after Trinidad and Tobago also pulled out. Manley believed that the rejection of his pro-federation policy in the 1961 referendum called for a renewed mandate from the electorate, but the JLP won the election of early 1962 by a fraction. Bustamante assumed the premiership that April and Manley spent his remaining few years in politics as leader of the opposition.

Jamaica received its independence on 6 August 1962. The new nation retained, however, its membership in the Commonwealth of Nations and adopted a Westminster-style parliamentary system. Bustamante, at the age of 78, became the nation's first prime minister.[67][68]

Jamaica under Bustamante

Bustamante subsequently became the first Prime Minister of Jamaica. The island country joined the Commonwealth of Nations, an organisation of ex-British territories.[69] Jamaica continues to be a Commonwealth realm, with the British monarch as King of Jamaica and head of state.

An extensive period of postwar growth transformed Jamaica into an increasingly industrial society. This pattern was accelerated with the export of bauxite beginning in the 1950s. The economic structure shifted from a dependence on agriculture that in 1950 accounted for 30.8 percent of GDP to an agricultural contribution of 12.9 percent in 1960 and 6.7 percent in 1970. During the same period, the contribution to the GDP of mining increased from less than 1 percent in 1950 to 9.3 percent in 1960 and 12.6 percent in 1970.[70]

Bustamante's government also continued the government's repression of Rastafarians. During the Coral Gardens incident, one prominent example of state violence against Rastafarians, where following a violent confrontation between Rastafarians and police forces at a gas station, Bustamante issued the police and military an order to "bring in all Rastas, dead or alive."[71] 54 years later, following a government investigation into the incident, the government of Jamaica issued an apology, taking unequivocal responsibility for the Bustamante government's actions and making significant financial reparations to remaining survivors of the incident.[72]

Jamaica under Donald Sangster and Hugh Shearer

Bustamante was succeeded as the prime minister in February 1967 by Donald Sangster, who in the same year died in office. Hugh Shearer, a protégé of Bustamante, succeeded Sangster and served from 1967 to 1972. Investments in tourism, bauxite mining, and light manufacturing industries fueled economic growth.

In October 1968 when the Shearer government banned Dr. Walter Rodney from returning to his teaching position at the University of the West Indies, so-called Rodney riots started. They were a part of an emerging black consciousness movement in the Caribbean.

Reggae

Jamaica's reggae music developed from Ska and rocksteady in the 1960s. The shift from rocksteady to reggae was illustrated by the organ shuffle pioneered by Jamaican musicians like Jackie Mittoo and Winston Wright and featured in transitional singles "Say What You're Saying" (1967) by Clancy Eccles and "People Funny Boy" (1968) by Lee "Scratch" Perry. The Pioneers' 1968 track "Long Shot (Bus' Me Bet)" has been identified as the earliest recorded example of the new rhythm sound that became known as reggae.[73]

Early 1968 was when the first bona fide reggae records were released: "Nanny Goat" by Larry Marshall and "No More Heartaches" by The Beltones. That same year, the newest Jamaican sound began to spawn big-name imitators in other countries. American artist Johnny Nash's 1968 hit "Hold Me Tight" has been credited with first putting reggae in the American listener charts. Around the same time, reggae influences were starting to surface in rock and pop music, one example being 1968's "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" by The Beatles.[74] Other significant reggae pioneers include Prince Buster, Desmond Dekker and Ken Boothe.

Bob Marley

The Wailers, a band started by Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer in 1963, is perhaps the most recognised band that made the transition through all three stages of early Jamaican popular music: ska, rocksteady and reggae.[75] The Wailers would go on to release some of the earliest reggae records with producer Lee Scratch Perry.[76] After the Wailers disbanded in 1974,[77] Marley then went on to pursue a solo career that culminated in the release of the album Exodus in 1977, which established his worldwide reputation and produced his status as one of the world's best-selling artists of all time, with sales of more than 75 million records.[78][79] He was a committed Rastafari who infused his music with a sense of spirituality.[80]

1970s and 1980s

Michael Manley

In the election of 1972, the PNP's Michael Manley defeated the JLP's unpopular incumbent Prime Minister Hugh Shearer. Under Manley, Jamaica established a minimum wage for all workers, including domestic workers. In 1974, Manley proposed free education from primary school to university. The introduction of universally free secondary education was a major step in removing the institutional barriers to the private sector and preferred government jobs that required secondary diplomas. The PNP government in 1974 also formed the Jamaica Movement for the Advancement of Literacy (JAMAL), which administered adult education programs with the goal of involving 100,000 adults a year.

Land reform expanded under his administration. Historically, land tenure in Jamaica has been rather inequitable. Project Land Lease (introduced in 1973), attempted an integrated rural development approach, providing tens of thousands of small farmers with land, technical advice, inputs such as fertilisers, and access to credit. An estimated 14 percent of idle land was redistributed through this program, much of which had been abandoned during the post-war urban migration and/or purchased by large bauxite companies.

The minimum voting age was lowered to 18 years, while equal pay for women was introduced.[81] Maternity leave was also introduced, while the government outlawed the stigma of illegitimacy. The Masters and Servants Act was abolished, and a Labour Relations and Industrial Disputes Act provided workers and their trade unions with enhanced rights. The National Housing Trust was established, providing "the means for most employed people to own their own homes," and greatly stimulated housing construction, with more than 40,000 houses built between 1974 and 1980.[81]

Subsidised meals, transportation and uniforms for schoolchildren from disadvantaged backgrounds were introduced,[82] together with free education at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.[82] Special employment programmes were also launched,[83] together with programmes designed to combat illiteracy.[83] Increases in pensions and poor relief were carried out,[84] along with a reform of local government taxation, an increase in youth training,[85] an expansion of day care centres.[86] and an upgrading of hospitals.[86]

A worker's participation program was introduced,[87] together with a new mental health law[85] and the family court.[85] Free health care for all Jamaicans was introduced, while health clinics and a paramedical system in rural areas were established. Various clinics were also set up to facilitate access to medical drugs. Spending on education was significantly increased, while the number of doctors and dentists in the country rose.[86]

One Love Peace Concert

The One Love Peace Concert was a large concert held in Kingston on April 22, 1978, during a time of political civil war in Jamaica between the rival Jamaican Labour Party and the People's National Party. The concert reached its peak during Bob Marley & The Wailers' performance of "Jammin'", when Marley joined the hands of political rivals Michael Manley (PNP) and Edward Seaga (JLP).

Edward Seaga

In the 1980 election, Edward Seaga and the JLP won by an overwhelming majority – 57 percent of the popular vote and 51 of the 60 seats in the House of Representatives. Seaga immediately began to reverse the policies of his predecessor by privatising the industry and seeking closer ties with the USA. Seaga was one of the first foreign heads of government to visit newly elected US president Ronald Reagan early the next year and was one of the architects of the Caribbean Basin Initiative, which was sponsored by Reagan. He delayed his promise to cut diplomatic relations with Cuba until a year later when he accused the Cuban government of giving asylum to Jamaican criminals.

Seaga supported the collapse of the Marxist regime in Grenada and the subsequent US-led invasion of that island in October 1983. On the back of the Grenada invasion, Seaga called snap elections at the end of 1983, which Manley's PNP boycotted. His party thus controlled all seats in parliament. In an unusual move, because the Jamaican constitution required an opposition in the appointed Senate, Seaga appointed eight independent senators to form an official opposition.

Seaga lost much of his US support when he was unable to deliver on his early promises of removing the bauxite levy, and his domestic support also plummeted. Articles attacking Seaga appeared in the US media and foreign investors left the country. Rioting in 1987 and 1988, the continued high popularity of Michael Manley, and complaints of governmental incompetence in the wake of the devastation of the island by Hurricane Gilbert in 1988, also contributed to his defeat in the 1989 elections.

Hurricane Gilbert

In 1988, Hurricane Gilbert produced a 19 ft (5.8 m) storm surge and brought up to 823 millimetres (32.4 in) of rain in the mountainous areas of Jamaica,[88] causing inland flash flooding. 49 people died.[89] Prime Minister Edward Seaga stated that the hardest hit areas near where Gilbert made landfall looked "like Hiroshima after the atom bomb."[90] The storm left US$4 billion (in 1988 dollars) in damage from destroyed crops, buildings, houses, roads, and small aircraft.[91] Two people eventually had to be rescued because of mudslides triggered by Gilbert and were sent to the hospital. The two people were reported to be fine. No planes were going in and out of Kingston, and telephone lines were jammed from Jamaica to Florida.

As Gilbert lashed Kingston, its winds knocked down power lines, uprooted trees, and flattened fences. On the north coast, 20 feet (6.1 m) waves hit Ocho Rios, a popular tourist resort where hotels were evacuated. Kingston's airport reported severe damage to its aircraft, and all Jamaica-bound flights were cancelled at Miami International Airport. Unofficial estimates state that at least 30 people were killed around the island. Estimated property damage reached more than $200 million. More than 100,000 houses were destroyed or damaged and the country's banana crop was largely destroyed. Hundreds of miles of roads and highways were also heavily damaged.[92] Reconnaissance flights over remote parts of Jamaica reported that 80 percent of the homes on the island had lost their roofs. The poultry industry was also wiped out; the damage from agricultural loss reached $500 million (1988 USD). Hurricane Gilbert was the most destructive storm in the history of Jamaica and the most severe storm since Hurricane Charlie in 1951.[91][93]

- Hurricane Gilbert approaching Jamaica on 12 September

- Buildings destroyed by Hurricane Gilbert

- People lined up to get water in the wake of Hurricane Gilbert

Birth of Jamaica's film industry

Jamaica's film industry was born in 1972 with the release of The Harder They Come, the first feature-length film made by Jamaicans. It starred reggae singer Jimmy Cliff, was directed by Perry Henzell, and was produced by Island Records founder Chris Blackwell.[94][95] The film is famous for its reggae soundtrack that is said to have "brought reggae to the world".[96] Jamaica's other popular films include 1976's Smile Orange, 1982's Countryman, 1991's The Lunatic, 1997's Dancehall Queen, and 1999's Third World Cop. Major figures in the Jamaican film industry include actors Paul Campbell and Carl Bradshaw, actress Audrey Reid, and producer Chris Blackwell.

1990s and 2000s

18 years of PNP rule

- Michael Manley, Prime Minister from 1989 to 1992 (his second term)

- P. J. Patterson, Prime Minister from 1992 to 2006

- Portia Simpson-Miller, Prime Minister from 2006 to 2007 (her first term) and from 2012 to 2016

The 1989 election. was the first election contested by the People's National Party since 1980, as they had boycotted the 1983 snap election. Prime Minister Edward Seaga announced the election date on January 15, 1989, at a rally in Kingston.[97] He cited emergency conditions caused by Hurricane Gilbert in 1988 as the reason for extending the parliamentary term beyond its normal five-year mandate.[98]

The date and tone of the election were shaped in part by Hurricane Gilbert, which made landfall in September 1988 and decimated the island. The hurricane caused almost $1 billion worth of damage to the island, with banana and coffee crops wiped out and thousands of homes destroyed. Both parties engaged in campaigning through the distribution of relief supplies, a hallmark of the Jamaican patronage system. Political commentators noted that prior to the hurricane, Edward Seaga and the JLP trailed Michael Manley and the PNP by twenty points in opinion polls. The ability to provide relief as the party in charge allowed Seaga to improve his standing among voters and erode the inevitability of Manley's victory. However, scandals related to the relief effort cost Seaga and the JLP some of the gains made immediately following the hurricane. Scandals that emerged included National Security Minister Errol Anderson personally controlling a warehouse full of disaster relief supplies and candidate Joan Gordon-Webley distributing American-donated flour in sacks with her picture on them.[99]

The election was characterised by a narrower ideological difference between the two parties on economic issues. Michael Manley facilitated his comeback campaign by moderating his leftist positions and admitting mistakes made as prime minister, saying he erred when he involved government in economic production and had abandoned all thoughts of nationalising industry. He cited the PNP's desire to continue the market-oriented policies of the JLP government, but with a more participatory approach.[100] Prime Minister Edward Seaga ran on his record of economic growth and the reduction of unemployment in Jamaica, using the campaign slogan "Don't Let Them Wreck It Again" to refer to Manley's tenure as prime minister.[101] Seaga during his tenure as prime minister emphasised the need to tighten public sector spending and cut close to 27,000 public sector jobs in 1983 and 1984.[102] He shifted his plans as elections neared with a promise to spend J$1 billion on a five-year Social Well-Being Programme, which would build new hospitals and schools in Jamaica.[103] Foreign policy also played a role in the 1989 election. Prime Minister Edward Seaga emphasised his relations with the United States, a relationship that saw Jamaica receiving considerable economic aid from the U.S. and additional loans from international institutions.[104] Manley pledged better relations with the United States while at the same time pledging to restore diplomatic relations with Cuba that had been cut under Seaga.[101] With Manley as prime minister, Jamaican-American relations had significantly frayed as a result of Manley's economic policies and close relations with Cuba.[105]

The PNP was ultimately victorious and Manley's second term focused on liberalising Jamaica's economy, with the pursuit of a free-market programme that stood in marked contrast to the interventionist economic policies pursued by Manley's first government. Various measures were, however, undertaken to cushion the negative effects of liberalisation. A Social Support Programme was introduced to provide welfare assistance for poor Jamaicans. In addition, the programme focused on creating direct employment, training, and credit for much of the population.[87] The government also announced a 50% increase in the number of food stamps for the most vulnerable groups (including pregnant women, nursing mothers, and children) was announced. A small number of community councils were also created. In addition, a limited land reform programme was carried out that leased and sold the land to small farmers, and land plots were granted to hundreds of farmers. The government also had an admirable record in housing provision, while measures were also taken to protect consumers from illegal and unfair business practices.[87]

In 1992, citing health reasons, Manley stepped down as prime minister and PNP leader. His former Deputy Prime Minister, Percival Patterson, assumed both offices. Patterson led efforts to strengthen the country's social protection and security systems—a critical element of his economic and social policy agenda to mitigate, reduce poverty and social deprivation.[106] His massive investments in modernisation of Jamaica's infrastructure and restructuring of the country's financial sector are widely credited with having led to Jamaica's greatest period of investment in tourism, mining, ICT and energy since the 1960s. He also ended Jamaica's 18-year borrowing relationship with the International Monetary Fund,[107] allowing the country greater latitude in pursuit of its economic policies.