History of American football

| Part of the American football series on the |

| History of American football |

|---|

| Origins of American football |

| Close relations to other codes |

| Topics |

The history of American football can be traced to early versions of rugby football and association football. Both games have their origin in multiple varieties of football played in the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century, in which a football is kicked at a goal or kicked over a line, which in turn were based on the varieties of English public school football games descending from medieval ball games.

American football resulted from several major divergences from association football and rugby football. Most notably the rule changes were instituted by Walter Camp, a Yale University athlete and coach who is considered to be the "Father of American Football". Among these important changes were the introduction of the hike spot, of down-and-distance rules, and of the legalization of forward pass and blocking.[1][2][3] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, gameplay developments by college coaches such as Eddie Cochems, Amos Alonzo Stagg, Parke H. Davis, Knute Rockne, and Glenn "Pop" Warner helped take advantage of the newly introduced forward pass. The popularity of college football grew as it became the dominant version of the sport in the United States for the first half of the 20th century. Bowl games, a college football tradition, attracted a national audience for college teams. Boosted by fierce rivalries and colorful traditions, college football still holds widespread appeal in the United States

The origin of professional football can be traced back to 1892,[4] with Pudge Heffelfinger's $500 ($16,956 in 2023 dollars) contract to play in a game for the Allegheny Athletic Association against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club. In 1920 the American Professional Football Association was formed. This league changed its name to the National Football League (NFL) two years later, and eventually became the major league of American football. Beginning primarily as a sport of Midwestern industrial towns in the United States, professional football eventually became a national phenomenon.

The modern era of American football can be considered to have begun after the 1932 NFL Playoff game, which was the first indoor championship game since 1902 and the first American football game to feature hash marks, forward passes anywhere behind the line of scrimmage, and the movement of the goalposts back to the goal line. Other innovations to occur immediately after 1932 were the introduction of the AP Poll in 1934, the tapering of the ends of the football in 1934, the awarding of the first Heisman Trophy in 1935, the first NFL draft in 1936 and the first televised game in 1939. Another important event was the American football game at the 1932 Summer Olympics, which combined with a similar demonstration game at 1933 World's Fair, led to the first College All-Star Game in 1934, which in turn was an important factor in the growth of professional football in the United States.[5] American football's explosion in popularity during the second half of the 20th century can be traced to the 1958 NFL Championship Game, a contest that has been dubbed the "Greatest Game Ever Played". A rival league to the NFL, the American Football League (AFL), began play in 1960; the pressure it put on the senior league led to a merger between the two leagues and the creation of the Super Bowl, which has become the most watched television event in the United States on an annual basis.[6]

History of American football before 1869

Predecessors

In Ancient Greece, men played a similar sport called Episkyros where they tried to throw a ball over a scrimmage while avoiding tackles.[7]

Forms of traditional football may have been played throughout Europe and beyond since antiquity. Many of these may have involved handling of the ball, and scrummage-like formations. These archaic forms of football, typically classified as mob football, could be played between neighboring towns and villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams, who could clash in a heaving mass of people struggling to drag an inflated pig's bladder by any means possible to markers at each end of a town. By some accounts, in some such events any means could be used to move the ball towards the goal, as long as it did not lead to manslaughter or murder.[8] These antiquated games went into sharp decline in the 19th century when the Highway Act 1835 was passed banning the playing of football on public highways.[9]

Football in the United States

Although there are some mentions of Native Americans playing football-like games, modern American football has its origins in the traditional football games played in the cities, villages and schools of Europe for many centuries before America was settled by Europeans. Early games appear to have had much in common with the traditional "mob football" played in England. The games remained largely unorganized until the 18th century, when intramural games of football began to be played. Organized varieties of football began to take form in 19th century in English public schools. According to legend, William Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it during a school football match in 1823, thus creating a new style of play in which running with the ball predominated instead of kicking. Football soon began to be played at colleges and universities in the United States. Each school played its own variety of football. Princeton University students played a game called "ballown" as early as 1820. A Harvard tradition known as "Bloody Monday" began in 1827, which consisted of a mass ballgame between the freshman and sophomore classes, played at The Delta, the space where Memorial Hall now stands. (A poem, "The Battle of the Delta", was written about the first match: "The Freshmen's wrath, to Sophs the direful spring / Of shins unnumbered bruised, great goddess sing!"[10]) In 1860, both the town police and the college authorities agreed that Bloody Monday had to go. The Harvard students responded by going into mourning for a mock figure called "Football Fightum", for whom they conducted funeral rites. The authorities held firm and it was a dozen years before football was once again played at Harvard. Dartmouth played its own version called "Old division football", the rules of which were first published in 1871, though the game dates to at least the 1830s. All of these games, and others, shared certain commonalities. They remained largely "mob" style games, with huge numbers of players attempting to advance the ball into a goal area, often by any means necessary. Rules were simple, and violence and injury were common.[11][12] The violence of these mob-style games led to widespread protests and a decision to abandon them. Yale, under pressure from the city of New Haven, banned the play of all forms of football in 1860.[11]

The game began to return to college campuses by the late 1860s. Yale, Princeton, Rutgers University, and Brown University began playing the popular "kicking" game during this time. In 1867, Princeton used rules based on those of the London Football Association.[11] A "running game", resembling rugby football, was taken up by the Montreal Football Club in Canada in 1868.[2] While the game between Rutgers and Brown is commonly considered the first American football game, several years prior in 1862, the Oneida Football Club formed as the oldest known football club in the United States. The team consisted of graduates of Boston's elite preparatory schools and played from 1862 to 1865.[13]

Intercollegiate football (1869–present)

Pioneer period (1869–1875)

On November 6, 1869, Rutgers University faced Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey) in a game that was played with a round ball and used a set of rules suggested by Rutgers captain William J. Leggett, based on the Football Association's first set of rules, which were an early attempt by the former pupils of England's public schools to unify the rules of their public schools games and create a universal and standardized set of rules for the game of football and bore little resemblance to the American game which would be developed in the following decades. It is still usually regarded as the first game of intercollegiate American football.[2][3][11][14] The game was played at a Rutgers field. Two teams of 25 players attempted to score by kicking the ball into the opposing team's goal. Throwing or carrying the ball was not allowed, but there was plenty of physical contact between players. The first team to reach six goals was declared the winner. Rutgers won by a score of six to four. A rematch was played at Princeton a week later under Princeton's own set of rules (one notable difference was the awarding of a "free kick" to any player that caught the ball on the fly, which was a feature adopted from the Football Association's rules; the fair catch kick rule has survived through to modern American game). Princeton won that game by a score of 8–0. Columbia joined the series in 1870, and by 1872 several schools were fielding intercollegiate teams, including Yale and Stevens Institute of Technology.[11]

Rutgers was first to extend the reach of the game. An intercollegiate game was first played in the state of New York when Rutgers played Columbia on November 2, 1872. It was also the first scoreless tie in the history of the fledgling sport.[15] Yale football started the same year and had its first match against Columbia, the nearest college to play football. It took place at Hamilton Park in New Haven and was the first game in New England. The game used a set of rules based on association football with 20-man sides, played on a field 400 by 250 feet. Yale won 3–0, Tommy Sherman scoring the first goal and Lew Irwin the other two.[16]

By 1873, the college students playing football had made significant efforts to standardize their fledgling game. Teams had been scaled down from 25 players to 20. The only way to score was still to bat or kick the ball through the opposing team's goal, and the game was played in two 45 minute halves on fields 140 yards long and 70 yards wide. On October 20, 1873, representatives from Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Rutgers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to codify the first set of intercollegiate football rules. Before this meeting, each school had its own set of rules and games were usually played using the home team's own particular code. At this meeting, a list of rules, based more on the Football Association's rules than the rules of the recently founded Rugby Football Union, was drawn up for intercollegiate football games.[11]

Harvard refused to attend the rules conference organized by the other schools and continued to play under its own code,[17] known as the "Boston game".[18][19] While Harvard's decision to maintain its code made it hard for them to schedule games against other American universities,[20] it agreed to play McGill University, from Montreal, in a two-game series in 1874. Harvard won the first game, in which its rules were used, 3–0. The second game, which was played under rugby regulations, did not have a winner as neither team managed to score.[21]

Harvard quickly took a liking to the rugby game, and its use of the try which, until that time, was not used in American football. The try would later evolve into the score known as the touchdown. On June 4, 1875, Harvard faced Tufts University in the first game between two American colleges played under rules similar to the McGill/Harvard contest, which was won by Tufts.[22] The rules included each side fielding 11 men at any given time, the ball was advanced by kicking or carrying it, and tackles of the ball carrier stopped play.[23] Further elated by the excitement of McGill's version of football, Harvard challenged its closest rival, Yale, to which the Bulldogs accepted. The two teams agreed to play under a set of rules called the "Concessionary Rules", which involved Harvard conceding something to Yale's soccer and Yale conceding a great deal to Harvard's rugby. They decided to play with 15 players on each team. On November 13, 1875, Yale and Harvard played each other for the first time ever, where Harvard won 4–0. At the first The Game—the annual contest between Harvard and Yale, among the 2000 spectators attending the game that day, was the future "father of American football" Walter Camp. Walter, who would enroll at Yale the next year, was torn between an admiration for Harvard's style of play and the misery of the Yale defeat and became determined to avenge Yale's defeat. Spectators from Princeton admired this type of game and it became the most popular version of football there.[11]

Walter Camp: Father of American football

Walter Camp is widely considered to be the most important figure in the development of American football.[1][2][3] As a youth, he excelled in sports like track, baseball, and association football, and after enrolling at Yale in 1876, he earned varsity honors in every sport the school offered.[1]

Following the introduction of rugby-style rules to American football, Camp became a fixture at the Massasoit House conventions where rules were debated and changed. Dissatisfied with what seemed to him to be a disorganized mob, he proposed his first rule change at the first meeting he attended in 1878: a reduction from fifteen players to eleven. The motion was rejected at that time but passed in 1880. The effect was to open up the game and emphasize speed over strength. Camp's most famous change, the establishment of the line of scrimmage and the snap from center to quarterback, was also passed in 1880. Originally, the snap was executed with the foot of the center. Later changes made it possible to snap the ball with the hands, either through the air or by a direct hand-to-hand pass.[1]

Camp's new scrimmage rules revolutionized the game, though not always as intended. Princeton, in particular, used scrimmage play to slow the game, making incremental progress towards the end zone during each down. Rather than increase scoring, which had been Camp's original intent, the rule was exploited to maintain control of the ball for the entire game, resulting in slow, unexciting contests. At the 1882 rules meeting, Camp proposed that a team be required to advance the ball a minimum of five yards within three downs. These down-and-distance rules, combined with the establishment of the line of scrimmage and forward pass, transformed the game from a variation of rugby football into the distinct sport and football code of American football.[1]

Camp was central to several more significant rule changes that came to define American football. In 1881, the field was reduced in size to 110 by 531⁄3 yards (100.6 by 48.8 meters). Several times in 1883, Camp tinkered with the scoring rules, finally arriving at four points for a touchdown, two points for kicks after touchdowns, two points for safeties, and five for field goals. Camp's innovations in the area of point scoring influenced rugby union's move to point scoring in 1890. In 1887, game time was set at two halves of 45 minutes each. Also in 1887, two paid officials—a referee and an umpire—were mandated for each game. A year later, the rules were changed to allow tackling below the waist, and in 1889, the officials were given whistles and stopwatches.[1]

The last, and arguably most important innovation, which would at last make American football uniquely "American", was the legalization of interference, or blocking, a tactic which was highly illegal under the rugby-style rules. Interference remains strictly illegal in both rugby codes. The prohibition of interference in the rugby game stems from the game's strict enforcement of its offside rule, which prohibited any player on the team with possession of the ball to loiter between the ball and the goal. At first, American players would find creative ways of aiding the runner by pretending to accidentally knock into defenders trying to tackle the runner. When Walter Camp witnessed this tactic being employed against his Yale team, he was at first appalled, but the next year had adopted the blocking tactics for his own team. During the 1880s and 1890s, teams developed increasingly complex blocking tactics including the interlocking interference technique known as the flying wedge or "V-trick formation", which was developed by Lorin F. Deland and first introduced by Harvard in a collegiate game against Yale in 1892. Despite its effectiveness, it was outlawed two seasons later in 1894 through the efforts of the rule committee led by Parke H. Davis, because of its contribution to serious injury.[24]

After his playing career at Yale ended in 1882, Camp was employed by the New Haven Clock Company until his death in 1925. Though no longer a player, he remained a fixture at annual rules meetings for most of his life, and he personally selected an annual All-American team every year from 1889 through 1924. The Walter Camp Football Foundation continues to select All-American teams in his honor.[25]

Scoring table

| Era | T.D. | F.G. | Con. | Con. (T.D.) | Saf. | Con. (S) |

Def. con. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1883 | 2 | 5 | 4 | – | 1 | – | – |

| 1883–1897 | 4 | 5 | 2 | – | 2 | – | – |

| 1898–1903 | 5 | 5 | 1 | – | 2 | – | – |

| 1904–1908 | 5 | 4 | 1 | – | 2 | – | – |

| 1909–1911 | 5 | 3 | 1 | – | 2 | – | – |

| 1912–1957 | 6 | 3 | 1 | – | 2 | – | – |

| 1958–present | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Note: For brief periods in the late 19th century, some penalties awarded one or more points for the opposing teams, and some teams in the late 19th and early 20th centuries chose to negotiate their own scoring system for individual games. | |||||||

Period of the American Intercollegiate Football Association (1876–1893)

On November 23, 1876, representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia met at the Massasoit House hotel in Springfield, Massachusetts to standardize a new code of rules based on the rugby game first introduced to Harvard by McGill University in 1874. The rules were based largely on the Rugby Football Union's code from England, though one important difference was the replacement of a kicked goal with a touchdown as the primary means of scoring (a change that would later occur in rugby itself, favoring the try as the main scoring event). Three of the schools—Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton—formed the Intercollegiate Football Association, as a result of the meeting. Yale did not join the group until 1879, because of an early disagreement about the number of players per team.[1]

The first game where one team scored over 100 points happened on October 25, 1884 when Yale routed Dartmouth 113–0. It was also the first time one team scored over 100 points and the opposing team was shut out.[27] The next week, Princeton outscored Lafayette by 140 to 0.[28]

The University of Michigan became the first school west of Pennsylvania to establish a college football team. On May 30, 1879 Michigan beat Racine College 1–0 in a game played in Chicago. The Chicago Daily Tribune called it "the first rugby-football game to be played west of the Alleghenies."[29] Other Midwestern schools soon followed suit, including the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Minnesota. The first western team to travel east was the 1881 Michigan team, which played at Harvard, Yale and Princeton.[30][31] The nation's first college football league, the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives (also known as the Western Conference), a precursor to the Big Ten Conference, was founded in 1895.[32]

On April 9, 1880 at Stoll Field, Transylvania University (then called Kentucky University) beat Centre College by the score of 13+3⁄4–0 in what is often considered the first recorded game played in the South.[33] The first game of "scientific football" in the South was the first instance of the Victory Bell rivalry between North Carolina and Duke (then known as Trinity College) held on Thanksgiving Day, 1888, at the Raleigh, North Carolina Athletic Park.[34][35]

On November 13, 1887 the Virginia Cavaliers and Pantops Academy fought to a scoreless tie in the first organized football game in the state of Virginia.[36] Students at UVA were playing pickup games of the kicking-style of football as early as 1870, and some accounts even claim that some industrious ones organized a game against Washington and Lee College in 1871, just two years after Rutgers and Princeton's historic first game in 1869. But no record has been found of the score of this contest. Washington and Lee also claims a 4 to 2 win over VMI in 1873.[37] Washington and Lee won 4–2.[37] Some industrious students of the two schools organized a game for October 23, 1869 – but it was rained out.[38]

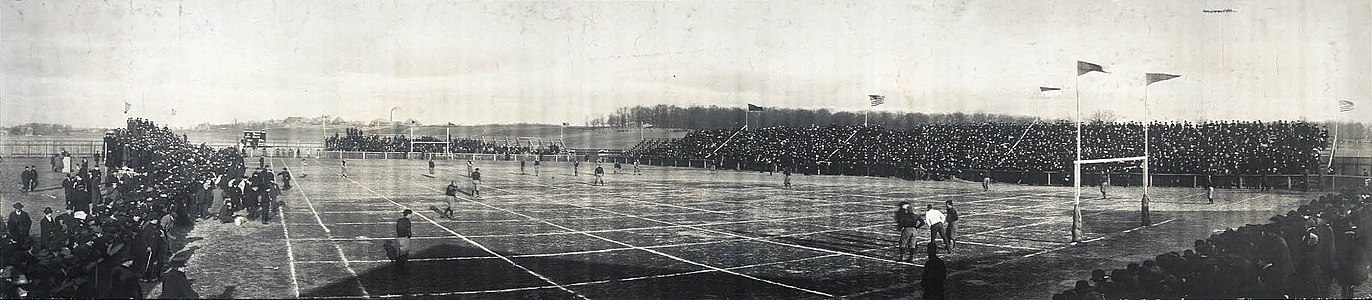

College football expanded greatly during the last two decades of the 19th century.[39] Several major rivalries date from this time period.[40]

November 1890 was an active time in the sport. In Baldwin City, Kansas, on November 22, 1890, college football was first played in the state of Kansas. Baker beat Kansas 22–9.[41] On the 27th, Vanderbilt played Nashville (Peabody) at Athletic Park and won 40–0. It was the first time organized football played in the state of Tennessee.[42] The 29th also saw the first instance of the Army–Navy Game. Navy won 24–0.[43]

The first nighttime football game was played in Mansfield, Pennsylvania on September 28, 1892 between Mansfield State Normal and Wyoming Seminary and ended at halftime in a 0–0 tie.[44] The Army-Navy game of 1893 saw the first documented use of a football helmet by a player in a game. Joseph M. Reeves had a crude leather helmet made by a shoemaker in Annapolis and wore it in the game after being warned by his doctor that he risked death if he continued to play football after suffering an earlier kick to the head.[45]

Period of Rules Committees and Conference (1894–1932)

The beginnings of the contemporary Southeastern Conference and Atlantic Coast Conference started in 1892. Upon organizing the first Auburn football team in that year, George Petrie arranged for the team to play the University of Georgia team at Piedmont Park in Atlanta, Georgia. Auburn won the game, 10–0, in front of 2,000 spectators. The game inaugurated what is known to college football fans as the Deep South's Oldest Rivalry. It was in 1894 the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) was founded on December 21, 1894, by Dr. William Dudley, a chemistry professor at Vanderbilt.[46] The original members were Alabama, Auburn, Georgia, Georgia Tech, North Carolina, Sewanee, and Vanderbilt. Clemson, Cumberland, Kentucky, LSU, Mercer, Mississippi, Mississippi A&M (Mississippi State), Southwestern Presbyterian University, Tennessee, Texas, Tulane, and the University of Nashville joined the following year in 1895 as invited charter members.[47] The conference was originally formed for "the development and purification of college athletics throughout the South".[48]

It is thought that the first forward pass in football occurred on October 26, 1895 in a game between Georgia and North Carolina when, out of desperation, the ball was thrown by the North Carolina back Joel Whitaker instead of punted and George Stephens caught the ball.[49] On November 9, 1895 John Heisman executed a hidden ball trick utilizing quarterback Reynolds Tichenor to get Auburn's only touchdown in a 6 to 9 loss to Vanderbilt. It was the first game in the south decided by a field goal.[50] Heisman later used the trick against Pop Warner's Georgia team. Warner picked up the trick and later used it at Cornell against Penn State in 1897.[51] He then used it in 1903 at Carlisle against Harvard and garnered national attention, the play was soon made illegal.[52]

The 1899 Sewanee Tigers are one of the all-time great teams of the early sport. The team went 12–0, outscoring opponents 322 to 10. Known as the "Iron Men", with just 13 men they had a six-day road trip with five shutout wins over Texas A&M; Texas; Tulane; LSU; and Ole Miss. It is recalled memorably with the phrase "... and on the seventh day they rested."[53][54] Grantland Rice called them "the most durable football team I ever saw."[55]

The first college football game in Oklahoma Territory occurred on November 7, 1895 when the 'Oklahoma City Terrors' defeated the Oklahoma Sooners 34 to 0. The Terrors were a mix of Methodist college students and high schoolers.[56] The Sooners did not manage a single first down. By next season, Oklahoma coach John A. Harts had left to prospect for gold in the Arctic.[57][58] Organized football was first played in the territory on November 29, 1894 between the Oklahoma City Terrors and Oklahoma City High School. The high school won 24 to 0.[57]

In 1891, the first Stanford football team was hastily organized and played a four-game season beginning in January 1892 with no official head coach. Following the season, Stanford captain John Whittemore wrote to Yale coach Walter Camp asking him to recommend a coach for Stanford. To Whittemore's surprise, Camp agreed to coach the team himself, on the condition that he finish the season at Yale first.[59] As a result of Camp's late arrival, Stanford played just three official games, against San Francisco's Olympic Club and rival California. The team also played exhibition games against two Los Angeles area teams that Stanford does not include in official results.[60][61] Camp returned to the East Coast following the season, but coached Stanford for two further years from 1894–1895.[62]

USC first fielded an American football team in 1888. Playing its first game on November 14 of that year against the Alliance Athletic Club, in which USC gained a 16–0 victory. Frank Suffel and Henry H. Goddard were playing coaches for the first team which was put together by quarterback Arthur Carroll; who in turn volunteered to make the pants for the team and later became a tailor.[63] USC faced its first collegiate opponent the following year in fall 1889, playing St. Vincent's College to a 40–0 victory.[63] In 1893, USC joined the Intercollegiate Football Association of Southern California (the forerunner of the SCIAC), which was composed of USC, Occidental College, Throop Polytechnic Institute (Cal Tech), and Chaffey College. Pomona College was invited to enter, but declined to do so. An invitation was also extended to Los Angeles High School.[64]

The Big Game between Stanford and California is the oldest college football rivalry in the West. The first game was played on San Francisco's Haight Street Grounds on March 19, 1892 with Stanford winning 14–10. The term "Big Game" was first used in 1900, when it was played on Thanksgiving Day in San Francisco. During that game, a large group of men and boys, who were observing from the roof of the nearby S.F. and Pacific Glass Works, fell into the fiery interior of the building when the roof collapsed, resulting in 13 dead and 78 injured.[65][66][67][68][69] On December 4, 1900, the last victim of the disaster (Fred Lilly) died, bringing the death toll to 22; the "Thanksgiving Day Disaster" remains the deadliest accident to kill spectators at a U.S. sporting event.[70]

In May 1900, Fielding H. Yost was hired as the football coach at Stanford University,[71] and, after traveling home to West Virginia, he arrived in Palo Alto, California, on August 21, 1900.[72] Yost led the 1900 Stanford team to a 7–2–1 record, outscoring opponents 154 to 20.[73] The next year in 1901, Yost was hired by Charles A. Baird as the head football coach for the Michigan Wolverines football team.[74] Led by Yost, Michigan became the first "western" national power. From 1901 to 1905, Michigan had a 56-game undefeated streak that included a 1902 trip to play in the first college football bowl game, which later became the Rose Bowl Game. During this streak, Michigan scored 2,831 points while allowing only 40.[75]

In 1906, citing concerns about the violence in American Football, universities on the West Coast, led by California and Stanford, replaced the sport with rugby union.[76] At the time, the future of American football was very much in doubt and these schools believed that rugby union would eventually be adopted nationwide.[76] Other schools followed suit and also made the switch included Nevada, St. Mary's, Santa Clara, and USC (in 1911).[76] However, due to the perception that West Coast football was inferior to the game played on the East Coast anyway, East Coast and Midwest teams shrugged off the loss of the teams and continued playing American football.[76] With no nationwide movement, the available pool of rugby teams to play remained small.[76] The schools scheduled games against local club teams and reached out to rugby union powers in Australia, New Zealand, and especially, due to its proximity, Canada. The annual Big Game between Stanford and California continued as rugby, with the winner invited by the British Columbia Rugby Union to a tournament in Vancouver over the Christmas holidays, with the winner of that tournament receiving the Cooper Keith Trophy.[76][77][78]

Violence and controversy (1905)

"No sport is wholesome in which ungenerous or mean acts which easily escape detection contribute to victory."

From its earliest days as a mob game, football was a very violent sport.[11] The 1894 Harvard-Yale game, known as the "Hampden Park Blood Bath", resulted in crippling injuries for four players; the contest was suspended until 1897. The annual Army-Navy game was suspended from 1894 to 1898 for similar reasons.[80] One of the major problems was the popularity of mass-formations like the flying wedge, in which a large number of offensive players charged as a unit against a similarly arranged defense. The resultant collisions often led to serious injuries and sometimes even death.[81] Georgia fullback Richard Von Albade Gammon died on the field from a concussion received against Virginia in 1897, causing some southern universities to temporarily stop their football programs.[82]

In 1905 there were 19 fatalities nationwide. President Theodore Roosevelt reportedly threatened to shut down the game if drastic changes were not made.[83] However, though he lectured on eliminating and reducing injuries, and held a meeting of football representatives from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton on October 9, 1905, he never threatened to completely ban football. He lacked the authority to abolish the game and was actually a fan who wanted to preserve it. The President's sons were playing football at the college and secondary levels at the time.[84]

Meanwhile, John H. Outland held an experimental game in Wichita, Kansas that reduced the number of scrimmage plays to earn a first down from four to three in an attempt to reduce injuries.[85] The Los Angeles Times reported an increase in punts and considered the game much safer than regular play but that the new rule was not "conducive to the sport".[86] Finally, on December 28, 1905, 62 schools met in New York City to discuss rule changes to make the game safer. As a result of this meeting, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, later named the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), was formed.[87] One rule change introduced in 1906, devised to open up the game and reduce injury, was the introduction of the legal forward pass. Though it was underutilized for years, this proved to be one of the most important rule changes in the establishment of the modern game.[88]

As a result of the 1905–1906 reforms, mass formation plays became illegal and forward passes legal. Bradbury Robinson, playing for visionary coach Eddie Cochems at St. Louis University, threw the first legal pass in a September 5, 1906, game against Carroll College at Waukesha. Other important changes, formally adopted in 1910, were the requirements that at least seven offensive players be on the line of scrimmage at the time of the snap, that there be no pushing or pulling, and that interlocking interference (arms linked or hands on belts and uniforms) was not allowed. These changes greatly reduced the potential for collision injuries.[89] Several coaches emerged who took advantage of these sweeping changes. Amos Alonzo Stagg introduced such innovations as the huddle, the tackling dummy, and the pre-snap shift.[90] Other coaches, such as Pop Warner and Knute Rockne, introduced new strategies that still remain part of the game.[91][92]

Besides these coaching innovations, several rules changes during the first third of the 20th century had a profound impact on the game, mostly in opening up the passing game. In 1914, the first roughing-the-passer penalty was implemented. In 1918, the rules on eligible receivers were loosened to allow eligible players to catch the ball anywhere on the field—previously strict rules were in place only allowing passes to certain areas of the field.[93] Scoring rules also changed during this time: field goals were lowered to three points in 1909[3] and touchdowns raised to six points in 1912.[94] In addition, 1912 saw the introduction of the 10-yard long end zone at each end of the field, thus reducing the size of the main field from 110 to 100 yards, and a fourth down was added, among other rule changes.[95]

Star players that emerged in the early 20th century include Jim Thorpe, Red Grange, and Bronko Nagurski; these three made the transition to the fledgling NFL and helped turn it into a successful league. Sportswriter Grantland Rice helped popularize the sport with his poetic descriptions of games and colorful nicknames for the game's biggest players, including Notre Dame's "Four Horsemen" backfield and Fordham University's linemen, known as the "Seven Blocks of Granite".[96]

In 1907 at Champaign, Illinois Chicago and Illinois played in the first game to have a halftime show featuring a marching band.[97] Chicago won 42–6. On November 25, 1911 Kansas and Missouri played the first homecoming football game.[98] The game was "broadcast" play-by-play over telegraph to at least 1,000 fans in Lawrence, Kansas.[99] It ended in a 3–3 tie. The game between West Virginia and Pittsburgh on October 8, 1921, saw the first live radio broadcast of a college football game when Harold W. Arlin announced that year's Backyard Brawl played at Forbes Field on KDKA. Pitt won 21–13.[100] On October 28, 1922, Princeton and Chicago played the first game to be nationally broadcast on radio. Princeton won 21–18 in a hotly contested game which had Princeton dubbed the "Team of Destiny".[101]

Notable intersectional games

In 1906 Vanderbilt defeated Carlisle 4–0, the result of a Bob Blake field goal.[102][103] In 1907 Vanderbilt fought Navy to a 6–6 tie. In 1910 Vanderbilt held defending national champion Yale to a scoreless tie.[103]

Helping Georgia Tech's claim to a title in 1917, the Auburn Tigers held undefeated, Chic Harley led Big Ten champion Ohio State to a scoreless tie the week before Georgia Tech beat the Tigers 68–7.[104] The next season, with many players gone due to World War I, a game was finally scheduled at Forbes Field with Pittsburgh. The Panthers, led by halfback Tom Davies, defeated Georgia Tech 32–0.[105]

1917 saw the rise of another Southern team in Centre of Danville, Kentucky. In 1921 Bo McMillin led Centre upset defending national champion Harvard 6–0 in what is widely considered one of the greatest upsets in college football history. The next year Vanderbilt fought Michigan to a scoreless tie at the inaugural game on Dudley Field, the first stadium in the South made exclusively for college football. Michigan coach Fielding Yost and Vanderbilt coach Dan McGugin were brothers-in-law, and the latter the protege of the former. The game featured the season's two best defenses and included a goal line stand by Vanderbilt to preserve the tie. Its result was "a great surprise to the sporting world".[106] Commodore fans celebrated by throwing some 3,000 seat cushions onto the field. The game features prominently in Vanderbilt's history.[107] That same year, Alabama upset Penn 9–7.[108]

Vanderbilt's line coach then was Wallace Wade, who in 1925 coached Alabama to the south's first Rose Bowl victory. This game is commonly referred to as "the game that changed the south".[109] Wade followed up the next season with an undefeated record and Rose Bowl tie.[110]

Modernization of intercollegiate American football (1933–1969)

In the early 1930s, the college game continued to grow, particularly in the South, bolstered by fierce rivalries such as the "South's Oldest Rivalry", between Virginia and North Carolina and the "Deep South's Oldest Rivalry", between Georgia and Auburn. Although before the mid-1920s most national powers came from the Northeast or the Midwest, the trend changed when several teams from the South and the West Coast achieved national success. Wallace William Wade's 1925 Alabama team won the 1926 Rose Bowl after receiving its first national title and William Alexander's 1928 Georgia Tech team defeated California in the 1929 Rose Bowl. College football quickly became the most popular spectator sport in the South.[111]

Several major modern college football conferences rose to prominence during this time period. The Southwest Athletic Conference had been founded in 1915. Consisting mostly of schools from Texas, the conference saw back-to-back national champions with Texas Christian University (TCU) in 1938 and Texas A&M in 1939.[112][113] The Pacific Coast Conference (PCC), a precursor to the Pac-12 Conference (Pac-12), had its own back-to-back champion in the University of Southern California which was awarded the title in 1931 and 1932.[112] The Southeastern Conference (SEC) formed in 1932 and consisted mostly of schools in the Deep South.[114] As in previous decades, the Big Ten continued to dominate in the 1930s and 1940s, with Minnesota winning 5 titles between 1934 and 1941, and Michigan (1933, 1947, and 1948) and Ohio State (1942) also winning titles.[112][115]

As it grew beyond its regional affiliations in the 1930s, college football garnered increased national attention. Four new bowl games were created: the Orange Bowl, Sugar Bowl, the Sun Bowl in 1935, and the Cotton Bowl in 1937. In lieu of an actual national championship, these bowl games, along with the earlier Rose Bowl, provided a way to match up teams from distant regions of the country that did not otherwise play. In 1936, the Associated Press began its weekly poll of prominent sports writers, ranking all of the nation's college football teams. Since there was no national championship game, the final version of the AP poll was used to determine who was crowned the National Champion of college football.[116]

The 1930s saw growth in the passing game. Though some coaches, such as Robert Neyland at Tennessee, continued to eschew its use and was the last college team to produce an undefeated, untied and unscored upon season in 1939. Several rules changes to the game had a profound effect on teams' ability to throw the ball. In 1934, the rules committee removed two major penalties—a loss of five yards for a second incomplete pass in any series of downs and a loss of possession for an incomplete pass in the end zone—and shrunk the circumference of the ball, making it easier to grip and throw. Players who became famous for taking advantage of the easier passing game included Alabama end Don Hutson and TCU passer "Slingin" Sammy Baugh.[117]

In 1935, New York City's Downtown Athletic Club awarded the first Heisman Trophy to University of Chicago halfback Jay Berwanger, who was also the first ever NFL Draft pick in 1936. The trophy was designed by sculptor Frank Eliscu and modeled after New York University player Ed Smith. The trophy recognizes the nation's "most outstanding" college football player and has become one of the most coveted awards in all of American sports.[118]

During World War II, college football players enlisted in the armed forces, some playing in Europe during the war. As most of these players had eligibility left on their college careers, some of them returned to college at West Point, bringing Army back-to-back national titles in 1944 and 1945 under coach Red Blaik. Doc Blanchard (known as "Mr. Inside") and Glenn Davis (known as "Mr. Outside") both won the Heisman Trophy, in 1945 and 1946 respectively. On the coaching staff of those 1944–1946 Army teams was future Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Vince Lombardi.[115][119]

The 1950s saw the rise of yet more dynasties and power programs. Oklahoma, under coach Bud Wilkinson, won three national titles (1950, 1955, 1956) and all ten Big Eight Conference championships in the decade while building a record 47-game winning streak. Woody Hayes led Ohio State to two national titles, in 1954 and 1957, and dominated the Big Ten conference, winning three Big Ten titles—more than any other school. Wilkinson and Hayes, along with Robert Neyland of Tennessee, oversaw a revival of the running game in the 1950s. Passing numbers dropped from an average of 18.9 attempts in 1951 to 13.6 attempts in 1955, while teams averaged just shy of 50 running plays per game. Nine out of ten Heisman trophy winners in the 1950s were runners. Notre Dame, one of the biggest passing teams of the decade, saw a substantial decline in success; the 1950s were the only decade between 1920 and 1990 when the team did not win at least a share of the national title. Paul Hornung, Notre Dame quarterback, did, however, win the Heisman in 1956, becoming the only player from a losing team ever to do so.[120][121]

In January of 1956, Bobby Grier became the first black player to participate in the Sugar Bowl. He is also regarded as the first black player to compete at a bowl game in the Deep South, though others such as Wallace Triplett had played in games like the 1948 Cotton Bowl in Dallas. Grier's team, the Pittsburgh Panthers, was set to play against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.[122] However, Georgia governor Marvin Griffin beseeched Georgia Tech to not participate in this racially-integrated game.[123][124] Griffin was widely criticized by news media leading up to the game, and protests were held at his mansion by Georgia Tech students. Despite the governor's objections, Georgia Tech upheld the contract and proceeded to compete in the bowl. In the game's first quarter, a pass interference call against Grier ultimately resulted in the Yellow Jackets' 7-0 victory. Grier stated that he has mostly positive memories about the experience, including the support from teammates and letters from all over the world.[125]

Modern intercollegiate football (1970–present)

Following the enormous success of the National Football League's 1958 championship game, college football no longer enjoyed the same popularity as the NFL, at least on a national level. While both games benefited from the advent of television, since the late 1950s, the NFL has become a nationally popular sport while college football has maintained strong regional ties.[126][127][128]

As professional football became a national television phenomenon, college football did as well. In the 1950s, Notre Dame, which had a large national following, formed its own network to broadcast its games, but by and large the sport still retained a mostly regional following. In 1952, the NCAA claimed all television broadcasting rights for the games of its member institutions, and it alone negotiated television rights. This situation continued until 1984, when several schools brought a suit under the Sherman Antitrust Act; the Supreme Court ruled against the NCAA and schools are now free to negotiate their own television deals. ABC Sports began broadcasting a national Game of the Week in 1966, bringing key matchups and rivalries to a national audience for the first time.[129]

New formations and play sets continued to be developed. Emory Bellard, an assistant coach under Darrell Royal at the University of Texas, developed a three-back option style offense known as the wishbone. The wishbone is a run-heavy offense that depends on the quarterback making last second decisions on when and to whom to hand or pitch the ball to. Royal went on to teach the offense to other coaches, including Bear Bryant at Alabama, Chuck Fairbanks at Oklahoma and Pepper Rodgers at UCLA; who all adapted and developed it to their own tastes.[130] The strategic opposite of the wishbone is the spread offense, developed by professional and college coaches throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Though some schools play a run-based version of the spread, its most common use is as a passing offense designed to "spread" the field both horizontally and vertically.[131] Some teams have managed to adapt with the times to keep winning consistently. In the rankings of the most victorious programs, Michigan, Notre Dame, and Texas are ranked first, second, and third in total wins.[132]

Growth of bowl games

| Growth of bowl games 1930–2020[133] | |

| Year | # of games |

|---|---|

| 1930 | 1 |

| 1940 | 5 |

| 1950 | 8 |

| 1960 | 8 |

| 1970 | 8 |

| 1980 | 15 |

| 1990 | 19 |

| 2000 | 25 |

| 2010 | 35 |

| 2020 | 40[134] |

In 1940, for the highest level of college football, there were only five bowl games (Rose, Orange, Sugar, Sun, and Cotton). By 1950, three more had joined that number and in 1970, there were still only eight major college bowl games. The number grew to eleven in 1976. At the birth of cable television and cable sports networks like ESPN, there were fifteen bowls in 1980. With more national venues and increased available revenue, the bowls saw an explosive growth throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In the thirty years from 1950 to 1980, seven bowl games were added to the schedule. From 1980 to 2010, an additional 20 bowl games were added to the schedule.[133][135] Some have criticized this growth, claiming that the increased number of games has diluted the significance of playing in a bowl game. Yet others have countered that the increased number of games has increased exposure and revenue for a greater number of schools, and see it as a positive development.[136]

With the growth of bowl games, it became difficult to determine a national champion in a fair and equitable manner. As conferences became contractually bound to certain bowl games (a situation known as a tie-in), match-ups that guaranteed a consensus national champion became increasingly rare. In 1992, seven conferences and independent Notre Dame formed the Bowl Coalition, which attempted to arrange an annual No. 1 versus No. 2 matchup based on the final AP poll standings. The Coalition lasted for three years; however, several scheduling issues prevented much success; tie-ins still took precedence in several cases. For example, the Big Eight and SEC champions could never meet, since they were contractually bound to different bowl games. The coalition also excluded the Rose Bowl, arguably the most prestigious game in the nation, and two major conferences—the Pac-10 and Big Ten—meaning that it had limited success. In 1995, the Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance, which reduced the number of bowl games to host a national championship game to three—the Fiesta, Sugar, and Orange Bowls—and the participating conferences to five—the ACC, SEC, Southwest, Big Eight, and Big East. It was agreed that the No. 1 and No. 2 ranked teams gave up their prior bowl tie-ins and were guaranteed to meet in the national championship game, which rotated between the three participating bowls. The system still did not include the Big Ten, Pac-10, or the Rose Bowl, and thus still lacked the legitimacy of a true national championship.[135][137]

Bowl Championship Series

In 1998, a new system was put into place called the Bowl Championship Series. For the first time, it included all major conferences (ACC, Big East, Big 12, Big Ten, Pac-10, and SEC) and all four major bowl games (Rose, Orange, Sugar and Fiesta). The champions of these six conferences, along with two "at-large" selections, were invited to play in the four bowl games. Each year, one of the four bowl games served as a national championship game. Also, a complex system of human polls, computer rankings, and strength of schedule calculations was instituted to rank schools. Based on this ranking system, the No. 1 and No. 2 teams met each year in the national championship game. Traditional tie-ins were maintained for schools and bowls not part of the national championship. For example, in years when not a part of the national championship, the Rose Bowl still hosted the Big Ten and Pac-10 champions.[137]

The system continued to change, as the formula for ranking teams was tweaked from year to year. At-large teams could be chosen from any of the Division I conferences, though only one selection—Utah in 2005—came from a BCS non-AQ conference. Starting with the 2006 season, a fifth game—simply called the BCS National Championship Game—was added to the schedule, to be played at the site of one of the four BCS bowl games on a rotating basis, one week after the regular bowl game. This opened up the BCS to two additional at-large teams. Also, rules were changed to add the champions of five additional conferences (Conference USA, the Mid-American Conference, the Mountain West Conference, the Sun Belt Conference and the Western Athletic Conference), provided that said champion ranked in the top twelve in the final BCS rankings, or was within the top 16 of the BCS rankings and ranked higher than the champion of at least one of the "BCS conferences" (also known as "AQ" conferences, for Automatic Qualifying).[137] Several times after this rule change was implemented, schools from non-AQ conferences played in BCS bowl games, most notably Boise State in the 2007 Fiesta Bowl, in which they upset Oklahoma in overtime.[138] In 2009, Boise State played TCU in the Fiesta Bowl, the first time two schools from BCS non-AQ conferences played each other in a BCS bowl game.[139] The last team from the non-AQ ranks to reach a BCS bowl game was Northern Illinois in 2012, which played in (and lost) the 2013 Orange Bowl.[140][141][142]

College Football Playoff

Due to the intensification of the college football playoff debate after nearly a decade of the sometimes disputable results of the BCS, the conference commissioners and Notre Dame's president voted to implement a postseason tournament to name a champion, which came to be called the College Football Playoff (CFP). CFP is the annual postseason tournament for the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS). Just as its predecessors, such a postseason tournament has failed to receive official sanctioning from the NCAA.

CFP began with the 2014 NCAA Division I FBS football season.[143] Originally, four teams played in two semifinal games, with the winners advancing to the College Football Playoff National Championship game.[144] The first season of the new system was not without controversy, however, after TCU and Baylor (both with only one loss) both failed to receive the support of the CFP selection committee.[145] The CFP was expanded to 12 teams as of the 2024 NCAA Division I FBS football season.

Professional football (1892–present)

Early players, teams, and leagues (1892–1919)

In the early 20th century, football began to catch on in the general population of the United States and was the subject of intense competition and rivalry, albeit of a localized nature. Although payments to players were considered unsporting and dishonorable at the time, a Pittsburgh area club, the Allegheny Athletic Association, of the unofficial western Pennsylvania football circuit, surreptitiously hired former Yale All-American guard Pudge Heffelfinger. On November 12, 1892, Heffelfinger became the first known professional football player. He was paid $500 to play in a game against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club. Heffelfinger picked up a Pittsburgh fumble and ran 35 yards for a touchdown, winning the game 4–0 for Allegheny. Although observers held suspicions, the payment remained a secret for years.[2][3][146][147]

On September 3, 1895 the first wholly professional game was played, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, between the Latrobe Athletic Association and the Jeannette Athletic Club. Latrobe won the contest 12–0.[2][3] During this game, Latrobe's quarterback, John Brallier became the first player to openly admit to being paid to play football. He was paid $10 plus expenses to play.[148] In 1897, the Latrobe Athletic Association paid all of its players for the whole season, becoming the first fully professional football team. In 1898, William Chase Temple took over the team payments for the Duquesne Country and Athletic Club, a professional football team based in Pittsburgh from 1895 until 1900, becoming the first known individual football club owner.[149]

Later that year, the Morgan Athletic Club, on the South Side of Chicago, was founded. This team later became the Chicago Cardinals, then the St. Louis Cardinals and now is known as the Arizona Cardinals, making them the oldest continuously operating professional football team.[3]

The first known professional football league, known as the National Football League (not the same as the modern league) began play in 1902 when several baseball clubs formed football teams to play in the league, including the Philadelphia Athletics, Pittsburgh Pirates and the Philadelphia Phillies. The Pirates' team the Pittsburgh Stars were awarded the league championship. However, the Philadelphia Football Athletics and Philadelphia Football Phillies also claimed the title.[150] A five-team tournament, known as the World Series of Football was organized by Tom O'Rouke, the manager of Madison Square Garden. The event featured the first-ever indoor pro football games. The first professional indoor game came on December 29, 1902, when the Syracuse Athletic Club defeated the "New York team" 5–0. Syracuse would go on to win the 1902 Series, while the Franklin Athletic Club won the Series in 1903. The World Series only lasted two seasons.[3][151]

The first black person to be paid for his play in football games is thought to be two-sport athlete Charles Follis, A member of the Shelby Steamfitters for five years starting in 1902, Follis turned professional in 1904.[152]

The game moved west into Ohio, which became the center of professional football during the early decades of the 20th century. Small towns such as Massillon, Akron, Portsmouth, and Canton all supported professional teams in a loose coalition known as the "Ohio League", the direct predecessor to today's National Football League. In 1906 the Canton Bulldogs–Massillon Tigers betting scandal became the first major scandal in professional football in the United States. It was the first known case of professional gamblers attempting to fix a professional sport. Although the Massillon Tigers could not prove that the Canton Bulldogs had thrown the second game, the scandal tarnished the Bulldogs' name and helped ruin professional football in Ohio until the mid-1910s.[153]

In 1915, the reformed Canton Bulldogs signed former Olympian and Carlisle Indian School standout Jim Thorpe to a contract. Thorpe became the face of professional football for the next several years and was present at the founding of the National Football League five years later.[3][154]

Early years of the NFL (1920–1932)

Formation

In 1920, the American Professional Football Association (APFA) was founded, in a meeting at a Hupmobile car dealership in Canton, Ohio. Jim Thorpe was elected the league's first president. After several more meetings, the league's membership was formalized. The original teams were:[94][155]

In its early years the league was little more than a formal agreement between teams to play each other and to declare a champion at season's end. Teams were still permitted to play non-league members. The 1920 season saw several teams drop out and fail to play through their schedule. Only four teams: Akron, Buffalo, Canton, and Decatur, finished the schedule. Akron claimed the first league champion, with the only undefeated record among the remaining teams.[94][156]

The APFA, which became the National Football League (NFL) in 1922,[157] had a limited number of black players. In the league's first seven years, nine African-Americans played in the APFA/NFL. Two black players took part in the league's inaugural season: Fritz Pollard and Bobby Marshall. In 1921, Pollard coached in the league, becoming the first African-American to do so.[158]

Expansion

In 1921, several more teams joined the league, increasing the membership to 22 teams. Among the new additions were the Green Bay Packers, which now has the record for longest use of an unchanged team name. Also in 1921, A. E. Staley, the owner of the Decatur Staleys, sold the team to player-coach George Halas, who went on to become one of the most important figures in the first half century of the NFL. In 1921, Halas moved the team to Chicago, but retained the Staleys nickname. In 1922 the team was renamed the Chicago Bears.[159][160] The Staleys won the 1921 AFPA Championship, over the Buffalo All-Americans in an event later referred to as the "Staley Swindle".[161]

By the mid-1920s, NFL membership had grown to 25 teams, and a rival league known as the American Football League was formed. The rival AFL folded after a single season, but it symbolized a growing interest in the professional game. Several college stars joined the NFL, most notably Red Grange from the University of Illinois, who was taken on a famous barnstorming tour in 1925 by the Chicago Bears.[159][162] Another scandal that season centered on a 1925 game between the Chicago Cardinals and the Milwaukee Badgers. The scandal involved a Chicago player, Art Folz, hiring a group of high school football players to play for the Milwaukee Badgers, against the Cardinals. This would ensure an inferior opponent for Chicago. The game was used to help prop up their win–loss percentage and as a chance of wrestling away the 1925 Championship away from the first place Pottsville Maroons. All parties were severely punished initially; however, a few months later the punishments were rescinded.[163] Also that year a controversial dispute stripped the NFL title from the Maroons and awarded it to the Cardinals.[164]

1932 NFL playoff game

At the end of the 1932 season, the Chicago Bears and the Portsmouth Spartans were tied with the best regular-season records. To determine the champion, the league voted to hold its first playoff game. Because of cold weather, the game was held indoors at Chicago Stadium, which forced some temporary rule changes. Chicago won, 9–0. The playoff proved so popular that the league reorganized into two divisions for the 1933 season, with the winners advancing to a scheduled championship game. A number of new rule changes were also instituted: the goal posts were moved forward to the goal line, every play started from between the hash marks, and forward passes could originate from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage (instead of the previous five yards behind).[165][166][167] In 1936, the NFL instituted the first draft of college players. With the first ever draft selection, the Philadelphia Eagles picked Heisman Trophy winner Jay Berwanger, but he declined to play professionally.[168] Also in that year, another AFL formed, but it also lasted only two seasons.[169]

Stability and growth of the NFL (1933–1969)

The 1930s represented an important time of transition for the NFL. League membership was fluid prior to the mid-1930s. In 1933, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles were founded. 1936 was the first year where there were no franchise moves,[170] prior to that year 51 teams had gone defunct.[155] In 1941, the NFL named its first Commissioner, Elmer Layden. The new office replaced that of President. Layden held the job for five years, before being replaced by Philadelphia Eagles co-owner Bert Bell in 1946.[171]

During World War II, a player shortage led to a shrinking of the league as several teams folded and others merged. Among the short-lived merged teams were the Steagles (Pittsburgh and Philadelphia) in 1943, the Card-Pitts (Chicago Cardinals and Pittsburgh) in 1944, and a team formed from the merger of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Yanks in 1945.[155][171]

1946 was an important year in the history of professional football, as that was the year when the league reintegrated. The Los Angeles Rams signed two African American players, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. Also that year, a competing league, the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), began operation.[171]

During the 1950s, additional teams entered the league. In 1950, the AAFC folded, and three teams from that league were absorbed into the NFL: the Cleveland Browns (who had won the AAFC Championship every year of the league's existence), the San Francisco 49ers, and the Baltimore Colts (not the same as the modern franchise, this version folded after one year). The remaining players were chosen by the now 13 NFL teams in a dispersal draft. Also in 1950, the Los Angeles Rams became the first team to televise its entire schedule, marking the beginning of an important relationship between television and professional football.[171] In 1952, the Dallas Texans went defunct, becoming the last NFL franchise to do so.[155] The following year a new Baltimore Colts franchise formed to take over the assets of the Texans. The players' union, known as the NFL Players Association, formed in 1956.[172]

The Greatest Game Ever Played

At the conclusion of the 1958 NFL season, the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants met at Yankee Stadium to determine the league champion. Tied after 60 minutes of play, it became the first NFL game to go into sudden death overtime. The final score was Colts 23, Giants 17. The game has since become widely known as "the Greatest Game Ever Played". It was carried live on the NBC television network, and the national exposure it provided the league has been cited as a watershed moment in professional football history, helping propel the NFL to become one of the most popular sports leagues in the United States.[172][173][174] Journalist Tex Maule said of the contest, "This, for the first time, was a truly epic game which inflamed the imagination of a national audience."[126]

American Football League and merger

In 1959, longtime NFL commissioner Bert Bell died of a heart attack while attending an Eagles/Steelers game at Franklin Field. That same year, Dallas businessman Lamar Hunt led the formation of the rival American Football League, the fourth such league to bear that name, with war hero and former South Dakota Governor Joe Foss as its first Commissioner. Unlike the earlier rival leagues, and bolstered by television exposure, the AFL posed a significant threat to NFL dominance of the professional football world. With the exception of Los Angeles and New York, the AFL avoided placing teams in markets where they directly competed with established NFL franchises. In 1960, the AFL began play with eight teams and a double round-robin schedule of fourteen games. New NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle took office the same year.[172]

The AFL became a viable alternative to the NFL as it made a concerted effort to attract established talent away from the NFL, signing half of the NFL's first-round draft choices in 1960. The AFL worked hard to secure top college players, many from sources virtually untapped by the established league: small colleges and predominantly black colleges. Two of the eight coaches of the Original Eight AFL franchises, Hank Stram (Texans/Chiefs) and Sid Gillman (Chargers) eventually were inducted to the Hall of Fame. Led by Oakland Raiders owner and AFL commissioner Al Davis, the AFL established a "war chest" to entice top talent with higher pay than they got from the NFL. Former Green Bay Packers quarterback Babe Parilli became a star for the Boston Patriots during the early years of the AFL, and University of Alabama passer Joe Namath rejected the NFL to play for the New York Jets. Namath became the face of the league as it reached its height of popularity in the mid-1960s. Davis's methods worked, and in 1966, the junior league forced a partial merger with the NFL. The two leagues agreed to have a common draft and play in a common season-ending championship game, known as the AFL-NFL World Championship. Two years later, the game's name was changed to the Super Bowl.[175][176][177] AFL teams won the next two Super Bowls, and in 1970, the two leagues completed their merger to form a new 26-team league. The resulting newly expanded NFL eventually incorporated some of the innovations that led to the AFL's success, such as including names on player's jerseys, official scoreboard clocks, national television contracts (the addition of Monday Night Football gave the NFL broadcast rights on all of the Big Three television networks), and sharing of gate and broadcasting revenues between home and visiting teams.[175]

Modern, post-merger NFL (1970–present)

The NFL continued to grow, eventually adopting some innovations of the AFL, including the two-point conversion. It has expanded several times to its current 32-team membership, and the Super Bowl has become a cultural phenomena across the United States. One of the most popular televised events annually in the United States,[6] it has become a major source of advertising revenue for the television networks that have carried it and it serves as a means for advertisers to debut elaborate and expensive commercials for their products.[178] The NFL has grown to become the most popular spectator sports league in the United States.[179]

One of the things that have marked the modern NFL as different from other major professional sports leagues is the apparent parity between its 32 teams. While from time to time, dominant teams have arisen, the league has been cited as one of the few where every team has a realistic chance of winning the championship from year to year.[180] The league's complex labor agreement with its players' union, which mandates a hard salary cap and revenue sharing between its clubs, prevents the richest teams from stockpiling the best players and gives even teams in smaller cities such as Green Bay and New Orleans the opportunity to compete for the Super Bowl.[181] One of the chief architects of this labor agreement was former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue, who presided over the league from 1989 to 2006.[182] In addition to providing parity between the clubs, the current labor contract, established in 1993 and renewed in 1998 and 2006, has kept player salaries low—the lowest among the four major league sports in the United States—[183] and has helped make the NFL the only major American professional sports league since 1993 not to suffer any player strike or work stoppage.[184]

Since taking over as commissioner before the 2006 season, Roger Goodell has made player conduct a priority of his office. Since taking office, several high-profile players have experienced trouble with the law, from Adam "Pacman" Jones to Michael Vick. In these and other cases, Commissioner Goodell has mandated lengthy suspensions for players who fall outside acceptable conduct limits.[185] Goodell, however, has remained a largely unpopular figure to many of the league's fans, who perceive him attempting to change the NFL's identity and haphazardly damage the sport.[186][187][188]

Other professional leagues

Minor professional leagues such as the original United Football League, Atlantic Coast Football League (ACFL), Seaboard Football League and Continental Football League existed in abundance in the 1960s and early 1970s, to varying degrees of success.[189] In 1970, Patricia Barzi Palinkas became the first woman to ever play on a men's semipro football team when she joined the Orlando Panthers of the ACFL.[190][191]

Several other professional football leagues have been formed since the AFL–NFL merger, though none have had the success of the AFL.[192][193] In 1974, the World Football League formed and was able to attract such stars as Larry Csonka away from the NFL with lucrative contracts.[194] However, most of the WFL franchises were insolvent and the league, despite having finished out its 1974 season, shut down late in its second season in 1975.[195]

In 1982, the original United States Football League formed as a spring league (starting play in 1983), and enjoyed moderate success during its first two seasons behind such stars as Jim Kelly and Herschel Walker.[196] In 1985, the league, which lost a considerable amount of money due to overspending on players, opted to gamble on moving its schedule to fall in 1986 (thus competing with the NFL and college/high school football) and filing a billion-dollar antitrust lawsuit against the NFL in an effort to stay afloat.[197][198][199] When the lawsuit only drew a three-dollar judgment, the first USFL folded.[200] A second incarnation of the USFL, connected in name only to the original, started play in 2022.[201]

The NFL founded a developmental league known as the World League of American Football with teams based in the United States, Canada, and Europe. The WLAF ran for two years as an intercontential league, in 1991 and 1992. After a two-year hiatus, the league (which would eventually become NFL Europe [League] and later NFL Europa) returned in 1995 as a purely European league, operating until 2007.[202]

In 2001, the original XFL was formed as a joint venture between the World Wrestling Federation (now World Wrestling Entertainment [WWE])[203] and the NBC television network. It folded after one season in the face of rapidly declining fan interest and a poor reputation. However, XFL stars such as Tommy Maddox and Rod "He Hate Me" Smart later saw success in the NFL.[204][205][206] In 2020, a new XFL began play. The league, owned by Vince McMahon in its first season is vastly different from the original incarnation; after going on hiatus due to COVID-19 pandemic midway through its first season, the league returned to play in 2023 under new management of a consortium led by former WWE wrestler Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson, Dany Garcia, and Gerry Cardinale (through Cardinale's fund RedBird Capital Partners).[207][208]

Youth and high school football

Football is a popular participatory sport among youth. One of the earliest youth football organizations was founded in Philadelphia, in 1929, as the Junior Football Conference. Organizer Joe Tomlin started the league to provide activities and guidance for teenage boys who were vandalizing the factory he owned. The original four-team league expanded to sixteen teams in 1933 when Pop Warner, who had just been hired as the new coach of the Temple University football team, agreed to give a lecture to the boys in the league. In his honor, the league was renamed the Pop Warner Conference.[209][210]

Today, Pop Warner Little Scholars—as the program is now known—enrolls over 300,000 young boys and girls ages 5–16 in over 5000 football and cheerleading squads, and has affiliate programs in Mexico and Japan.[210] Other organizations, such as the Police Athletic League,[211] Upward,[212] and the National Football League's NFL Youth Football Program also manage various youth football leagues.[213]

Football is a popular sport for high schools in the United States. The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) was founded in 1920 as an umbrella organization for state-level organizations that manage high school sports, including high school football. The NFHS publishes the rules followed by most local high school football associations.[209][214] More than 13,000 high schools participate in football, and in some places high school teams play in stadiums that rival college-level facilities. For example, the school district serving the Houston suburb of Katy, Texas opened a 12,000-seat stadium in 2017 that cost over $70 million to host the district's eight high school teams.[215] The growth of high school football and its impact on small town communities has been documented by landmark non-fiction works such as the 1990 book Friday Night Lights and the subsequent fictionalized film and television series.[216]

American football outside the United States

American football has been played outside the U.S. since the 1920s and accelerated in popularity after World War II, especially in countries with large numbers of U.S. military personnel, who often formed a substantial proportion of the players and spectators.[217][218]

In 1998, the International Federation of American Football, was formed to coordinate international amateur competition. At present, 45 associations from the Americas, Europe, Asia and Oceania are organized within the IFAF, which claims to represent 23 million amateur athletes.[219] The IFAF, which is based in La Courneuve, France,[220] organizes the quadrennial World Championship of American Football.[221]

A long-term goal of the IFAF is for American football to be accepted by the International Olympic Committee as an Olympic sport.[222] The only time that the sport was played was at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, but as a demonstration sport. Among the various problems the IFAF has to solve in order to be accepted by the IOC are building a competitive women's division, expanding the sport into Africa, and overcoming the current worldwide competitive imbalance that is in favor of American teams.[223]

Similar codes of football

Other codes of football share a common history with American football. Canadian football is a form of the game that evolved parallel to American football. While both games share a common history, there are some important differences between the two.[224] A more modern sport that derives from American football is Arena football, designed to be played indoors inside of ice hockey or basketball arenas. The game was invented in 1981 by Jim Foster and the Arena Football League was founded in 1987 as the first major professional league to play the sport. Several other indoor football leagues have since been founded and continue to play today.[225]

American football's parent sport of rugby continued to evolve. Today, two distinct codes known as rugby union and rugby league are played throughout the world. Since the two codes split following a schism on how the sport should be managed in 1895, the history of rugby league and the history of rugby union have evolved separately.[226] Both codes have adopted innovations parallel to the American game; the rugby union scoring system is almost identical to the American game, while rugby league uses a gridiron-style field and a six-tackle rule similar to the system of downs in American Football.

Another game that can trace it history to English public school football games is the Australian rules football, which was first played in Melbourne, Victoria in 1858. The game, also known as Australian football or Aussie rules, is played between teams of 18 players on an oval field, often a modified cricket ground. Points are scored by kicking the oval ball between the middle goal posts (worth six points) or between a goal and behind post (worth one point). The Melbourne Football Club published the first laws of Australian football in May 1859, which predates American football by at least 10 years, and making it the oldest of the world's major football codes.[227][228]

Gaelic football is an Irish-specific sport, that can also trace its roots to the early days of football. The game is played between two teams of 15 players on a rectangular grass pitch. The objective of the sport is to score by kicking or punching the ball into the other team's goals (3 points) or between two upright posts above the goals and over a crossbar 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) above the ground (1 point). Unlike other similar football codes, the game ball is round (a spherical leather ball resembling a volleyball), and players advance it up the field with a combination of carrying, bouncing, kicking, hand-passing, and soloing (dropping the ball and then toe-kicking the ball upward into the hands). The game playing code was formally arranged by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in 1885, and was played in the 1904 Summer Olympics as a demonstration sport.

See also

- American football rules

- Comparison of American football and rugby league

- Comparison of American football and rugby union

- Comparison of Canadian and American football

- Gridiron football

- History of American football positions

- Homosexuality in American football

- History of association football

- History of the football helmet

- List of historically significant college football games

- Timeline of college football in Kansas

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g "Camp and His Followers: American Football 1876–1889" (PDF). The Journey to Camp: The Origins of American Football to 1889. Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "The History of Football". The History of Sports. Saperecom. 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "NFL History3039–1910". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ^ "Birth of Pro Football | Pro Football Hall of Fame Official Site". www.profootballhof.com.

- ^ Ray Schmidt (May 2004). "The Olympics Game" (PDF). College Football Historical Society Newsletter. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "NFL:America's Choice" (PDF). National Football League. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Greek Episkyros (Ball Game)". Health and Fitness History.

- ^ "History of Football – Britain, the home of Football". FIFA. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ "An Act to consolidate and amend the Laws relating to Highways in that Part of Great Britain called England" (PDF). Legislation.gov.uk. August 31, 1835. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (April 13, 1964). Three Centuries of Harvard, 1636–1936. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674888913 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "No Christian End!" (PDF). The Journey to Camp: The Origins of American Football to 1889. Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2010.