Hippolyte Bouchard

Hippolyte Bouchard | |

|---|---|

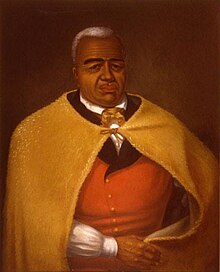

Hippolyte Bouchard, oil on canvas by José Gil de Castro | |

| Born | André Paul Bouchard 15 January 1780[1][A] |

| Died | 4 January 1837 (aged 56) near Palpa, North Peru, Peru–Bolivian Confederation |

| Parents |

|

Hippolyte or Hipólito Bouchard (15 January 1780[1][A] – 4 January 1837), known in California as Pirata Buchar, was a French-born Argentine[2][3] sailor and corsair (pirate) who fought for Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

During his first campaign as an Argentine corsair he attacked the Spanish colonies of Chile and Peru, under the command of the Irish-Argentine Admiral William Brown. During his overseas voyage he blockaded the port of Manila, Philippines. In Hawaii, he recovered an Argentine privateer which had been seized by mutineers. He also met the local ruler, King Kamehameha I. His forces occupied Monterey, California, then a Spanish colony, raised the Argentine flag and held the town for six days. After raiding Monterey, he plundered Mission San Juan Capistrano in Southern California. Toward the end of the voyage Bouchard raided Spanish ports in Central America.[4] His second homeland remembers him as a hero and patriot; several places are named in his honour.

Early life

Bouchard was born in a small village close to Saint-Tropez, Bormes-les-Mimosas, on the Côte d'Azur (French Riviera) in 1780[1][A] The son of André Louis Bouchard and Thérèse Brunet was baptized as André Paul but eventually went by the name Hippolyte. He initially worked in the French merchant fleet, then served in the French Navy in their campaigns against the English, thus starting his life at sea. After many campaigns including the French Campaign in Egypt by the future Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the Saint-Domingue expedition, disillusioned with the direction of the French Revolution, Bouchard went to Argentina in 1809 and, to aid the May Revolution, became a part of the National Argentine Fleet, led by Azopardo. On 2 March 1811 he fought for the first time under the Argentine Flag when the Spanish Captain Jacinto de Romarate defeated the first Argentine flotilla at San Nicolás de los Arroyos, and in July and August of that year he played a major role in defending the City of Buenos Aires from a Spanish blockade. In March 1812 Bouchard joined the Mounted Grenadiers Regiment led by José de San Martín and took part in the Battle of San Lorenzo in 1813, where he captured a Spanish flag and therefore was granted Argentine citizenship.[3] Some months later he married Norberta Merlo.[5]

Campaign with William Brown

In 1815 Bouchard started a naval campaign under the command of Admiral William Brown, wherein he attacked the fortress of El Callao and the Ecuadorian city of Guayaquil. On 12 September 1815 he was granted a corsair license to fight the Spanish aboard the French-built corvette Halcón, which had been bought for the Argentine State by Vicente Anastacio Echeverría. Most of the officers were French, except for the second commander, the Englishman Robert Jones, and Ramón Freire. Before weighing anchor a conflict between Bouchard and his superiors arose when the expedition's agent, Severino Prudant, promoted several sailors. Echeverría intervened and settled the conflict.

The campaign fleet was composed of the frigate Hercules under the command of William Brown, the Santísima Trinidad under the command of his brother, Miguel Brown, the schooner Constitución under the command of Oliverio Russell, and the Halcón. The Hércules and Santísima Trinidad set sail from Montevideo on 24 October; the other two ships departed five days later. The plan was for all four ships to rendezvous at Mocha Island where they would establish a plan of operation. The Brown brothers arrived at the island on 28 December, with the Halcón arriving the following day. Upon arrival Bouchard announced that while circumnavigating Cape Horn his ship was exposed to fourteen days of severe weather, and it was on that basis that he had concluded that the Constitución had sunk (neither the ship nor its crew were ever seen again). On 31 December Brown and Bouchard agreed to operate together during the first hundred days of 1816. Any plunder would be divided as follows: two parts to Brown, as the commander-in-chief, and one-and-a-half parts each for the Santísima Trinidad and the Halcón.[6] Bouchard and Miguel Brown subsequently set course for the Peruvian coast, while the Hércules sailed to the Juan Fernández Islands in order to free a number of patriots that were being held prisoner there.

On 10 January 1816 the three vessels met again near the fortress of El Callao. The ships formed a blockade and bombarded Guayaquil and its nearby fortification. The following day the group seized the brigantine San Pablo, which was used to transport sick and injured sailors as well as the liberated prisoners. On the 13th the frigate Gobernadora was captured, and Lt. Colonel Vicente Banegas, officer of the Republican Army of Nueva Granada, joined the fleet. Four more ships were commandeered on the 18th, including the schooner Carmen and the brig Místico along with two other ships, one of which was sacked and sunk. On 21 January the Argentine fleet again attacked the fortress, sinking the frigate Fuente Hermosa in the process. Seven days later two more vessels were captured, the frigates Candelaria and Consecuencia. The next day the expanded fleet sailed north in search of the Guayas River. On 7 February the Argentine contingent arrived at Puná Island, near Guayaquil. As they arrived, William Brown ordered Bouchard and his brother to stay close to the seven ships they had captured. Brown took the command of the Santísima Trinidad, with which he wanted to attack Guayaquil. The next day his attack demolished the fort of Punta de Piedras, located some five leagues from Guayaquil. However, on 9 February Brown failed in his attempt to take the castle of San Carlos, and was instead captured by the royalist forces. After a long negotiation, the Argentine corsairs traded Brown for the Candelaria, three brigantines and five correspondence chests that had been taken from the Consecuencia.[7]

After three days, Bouchard informed Brown that his ship was close to sinking and that the officers wished to return to Buenos Aires. He then asked for a division of the booty, and received the Consecuencia, the Carmen, and 3,475 pesos as compensation (he had to leave the Halcón behind). Bouchard elected to return to Buenos Aires via Cape Horn, and it was there that new incidents with the crew arose, many of which were solved with violence, such as a duel with one of his sergeants. When an officer on the Carmen notified Bouchard that the ship was in imminent danger of foundering, Bouchard nonetheless ordered the man to continue the journey. As a result, the crew mutinied and headed to the Galápagos Islands. The Consecuencia, with Bouchard still in command, made port in Buenos Aires on 18 June.[8]

Campaign with La Argentina

The beginning of the campaign

Bouchard decided to stay with the frigate Consecuencia for his next campaign. In concert with Vicente Echevarría the ship's name was changed to La Argentina. Preparing the ship was not an easy task, as it was very heavy and some 100 metres (330 feet) long. Echevarría acquired 34 artillery pieces and hired experienced carpenters to mount them in place. Upon Bouchard's request, the Argentine State gave him 4 bronze cannons and 12 iron cannons, 128 guns, and 1,700 cannonballs, but he was unable to requisition small arms such as boarding guns or sabers (even cavalry sabers).[9] Even more difficult was finding the 180 men he needed for a crew, especially given Bouchard's reputation as ill-tempered (which dogged him after the conflicts in the Pacific)[citation needed]. Most of the sailors he did enlist were foreigners, though some were from the provinces of Corrientes and Entre Ríos.

On 25 June, with La Argentina still in port, a sailor struck one of his superiors, an act of insubordination. When Bouchard discovered this he ordered the sailor's arrest, provoking general unrest. One of the fellow sailors attacked Commander Sommers, who killed him in self-defense. This did not prevent other members of the crew from barricading themselves inside the ship, which led to their being forcibly removed by the marine infantry, led by Sommers. Two crewmen were killed in the conflict, and four others were wounded. Following the altercation Echevarría sent a letter to Supreme Director Juan Martín de Pueyrredón explaining that the incident was the result of the crew having been stuck in Buenos Aires for an extended period, and that chances of further outbreaks would be lessened once the ship put to sea. Two days later La Argentina headed to Ensenada de Barragán, which started rumors flying that Bouchard had deserted the service. In reality, the frigate disembarked under the authority of a general order which required that ships that were subjected to loading delays and such but were otherwise seaworthy leave the harbor in order that they not be caught at anchor should the Spanish attempt an invasion.

On 27 June Bouchard obtained the Argentine corsair patent (a "letter of marque") that authorized him to prey on Spanish commerce, the countries of Spain and Argentina being in a state of war at the time.[7] On 9 July 1817 (the first anniversary of the signing of the Argentine Declaration of Independence) Bouchard set out from Ensenada de Barragán in command of La Argentina on a two-year voyage, intending to travel across the Atlantic to the African coast in order to circumnavigate around the Cape of Good Hope and engage a fleet of ships operated by the Company of the Philippines that had sailed from Spain to India. However, a fire broke out on 19 July which the crew had to fight for hours until it was extinguished. Consequently, when the ship subsequently arrived in the Indian Ocean it headed northeast to Madagascar, where it laid up at Tamatave (on the east of the island) for a period of two months while repairs were effected. Once in Tamatave, a British officer requested Bouchard's assistance in preventing four slaver ships (three British and one French) from leaving the island, whereupon Bouchard offered the use of all his available troops. The La Argentina seized the slavers' food supplies and recruited five French sailors prior to departing Madagascar with the intent of launching attacks on the Spanish merchant vessels that sailed in the region. Much of the crew was soon afflicted with scurvy, which required that ship's operations be conducted by those few sailors who had escaped illness. On 18 October La Argentina encountered an American frigate that passed on the news that the Company of the Philippines had ended trade with India three years prior.

The Pirates

La Argentina headed toward the Philippines, weathering several storms in the Sunda Strait (that divides the islands of Java and Sumatra, and connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean) along the way. On 7 November Bouchard decided to land at Java in order to let his sick crew members recuperate. After leaving the island, La Argentina continued on its journey to the Philippines. Traveling through the region was fraught with danger due to the presence of Malayan pirates, and was compounded by the crew's weakened condition. The pirate ships were equipped with cannons in the prow and in the stern, and were outfitted with one mast and many oars. The Lanun as they were known to the Malay people were not seen until the morning of 7 December, when the watchman sighted four small ships. Combat was delayed until midday when the largest of the pirate vessels attempted to close in on La Argentina. It arrived towing a boat of the frigate that had visited him in search of provisions. [10] As Bouchard preferred to instigate boarding actions and relied on hand-to-hand combat he therefore chose to forgo firing upon the aggressor. La Argentina's crew prevailed and were ordered to take the ship; in the meantime, the other would-be attackers fled. Bouchard convened a "war council" to judge the prisoners, sentencing all of them to death, save for the youngest. The condemned prisoners were returned to their ship and locked below the deck; the damaged vessel was subjected to salvo after salvo of cannon fire from La Argentina until she sank with all hands aboard.[11]

The Sulu Islands

After passing through the Makassar Strait, La Argentina crossed the Celebes Sea and made landfall on the island of Joló. Bouchard arrived in the archipelago on January 2, 1818, and remained there for five days. Large numbers of underwater rocks and strong currents made navigation difficult in these seas. Its inhabitants considered valor as the first of the virtues and always boasted of being invincible. His whole life was based on piracy that regulated his economy, his military forces and his social life. While the frigate's crew was negotiating with the natives to secure adequate supplies, sentries were stationed, loaded with muskets, to repel any possible attack by the Joloans. At night a sentry perceived movements and cautiously alerted the whole crew. When they confirmed that the boats dangerously lurked to the frigate, all the men prepared their arms and when being at a distance of a hundred yards the order was given to open fire. The Joloans were surprised and quickly fled. After a series of incidents finally the monarch appeared with a richly adorned boat. It brought with it a great quantity of fruits and vegetables, besides four buffaloes for the hungry sailors. From that moment they were able to complete the watering without being disturbed and the islanders were allowed to trade freely with the crew of the frigate.[12]

The Philippines

Then headed to the Spanish port at Manila for the purpose of establishing a blockade. Upon arrival on 31 January 1818 the Argentines stopped an English frigate attempting to dock to determine whether or not it carried supplies for the Spanish colony. Bouchard attempted to hide his origin, but the frigate's captain discerned what his true intentions were and warned the Spanish authorities of his intentions. The City of Manila had fortified walls and was protected by a redoubt, Fort Santiago, with powerful artillery. Bouchard instead began to plunder nearby vessels, all the while staying clear of the Spanish cannons. For the next two months La Argentina captured a total of 16 ships through the use of intimidating cannon fire and quick boardings. To further tighten the siege over the capital of the archipelago, Bouchard arranged for an armed Pontin with 23 crew members to block the strait of San Bernardino under the command of second captain Sommers. In that action they captured a felluca and a galley.[13] While Manila's inhabitants fell into a state of despair as the price of food doubled, and even tripled. The governor sent two armed merchant vessels, accompanied by a corvette, to engage La Argentina. The group missed its opportunity, however, as Bouchard had already departed the area on 30 March.[14]

Few days after, the ship sighted a brigantine from the Mariana Islands. When it noticed the proximity of La Argentina, it fled to the port of Santa Cruz. The Argentine frigate was unable to approach the harbor because of its draft, so Bouchard ordered Sommers, Greissac and Van Buren to use three boats to capture the ship. The three officers and many crew members started to approach the brigantine that had not arrived to the port. Owing to the speed of his boat, Sommers went ahead and managed to reach the brigantine. But the cutter leading to Sommers was overturned by the crew of the brig that threw moorings to their masts. From the deck of the brig, they attacked the defenseless men in the water, killing fourteen.[15] The others were rescued by Greissac and Van Buren and returned to the frigate. Bouchard wanted to revenge the deaths, but in order to capture the brigantine he needed a vessel with a smaller stern. So he ordered Greissac to lead some sailors and take any of the schooners that sailed near the port. Once captured, Bouchard put a number of cannons in her. He placed Greissac and Oliver in command of her with 35 sailors. The schooner attacked on 10 April but the brigantine's crew had fled. Continuing their navigation, they reached the northern end of the island and captured a pontoon that carried the Royal Situado to the islands Batanes.[16] However, because of the strong winds it was possible to send only an officer and eight sailors to sail the vessel. The schooner was in sight until 15 April, possibly the insubordination was caused by the value of the shipment.[17] La Argentina traveled to the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii) to find new crew members to replace those who had died from scurvy. Bouchard hired Peter Corney to captain the Santa Rosa, a captured ship whose crew had mutinied.[18] Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. in his paper: “Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm”, stated that his second ship, the Santa Rosa had a multi-ethnic crew which included Filipinos.[19] Mercene, writer of the Book “Manila Men”, proposes that those Manilamen were recruited in San Blas, an alternative port to Acapulco Mexico where several Filipinos had settled during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade era. The Filipinos who settled in San Blas were escapees from Spanish slavery in the Manila Galleons, upon meeting Hippolyte Bouchard who worked for the Argentinians that revolted against Spain, the common grievance the Filipinos shared against the Spaniards, which they shared with the Argentines caused them to mutiny and join the rebel Argentines.[20]

Sandwich Islands (Hawaii)

On 17 August Bouchard arrived at Kealakekua Bay on the western coast of the island of Hawaii. A group of natives came close to the ship in a canoe and informed them, in English, that a corvette, which used to be Spanish but had been sold to King Kamehameha I, was also at anchor in the harbor. They also told them that, on the previous night, a frigate had departed. Bouchard decided to chase the frigate, which they found becalmed. He ordered Sheppard to take a rowboat to ask the frigate's commander for information about the ship in the Hawaiian harbor. Sheppard found out that it was the Santa Rosa or the Chacabuco, a corvette that had weighed anchor at Buenos Aires almost the same day the La Argentina had. The crew of Santa Rosa had mutinied near Chile's coast and headed to Hawaii, where the crew had attempted to sell the vessel to the Hawaiian king.[21] The French privateer forced the frigate to return to the harbor, because he suspected that among its crew were hiding some of the mutineers. While investigating the men he found nine men he had seen in Buenos Aires and punished them. After an interrogation he found out the revolt's leaders were hiding in Kauai Island.

When he arrived at the harbor he found the Santa Rosa almost dismantled, therefore he decided to meet King Kamehameha I wearing his uniform of Lieutenant Colonel of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. During the meeting Bouchard demanded the restitution of the corvette. However, the king argued he had paid 600 hundredweight of sandalwood for her and that he deserved a compensation. Bouchard traded his sword and commanders hat, along with an honorific title of Lieutenant Colonel of the United Provinces. Argentine historian, author and 6th President of Argentina Bartolomé Mitre wrote of this agreement as the first "international treaty" signed by Argentina with a non-Latin American country, an interpretation dismissed by later historians.[22] Historian Pacho O'Donnell affirms that Hawaii was the first state that recognized Argentina's independence.[23] After the negotiation, Bouchard returned to the Bay of Kealekekua, conditioned the Santa Rosa and waited for the king to send him the agreed provisions. As this did not occur he went with his warships to rejoin the monarch at his residence in Kailua.[24] For the risk involved two warships in his capital, Kamehameha indicated that it could be provisioned in Maui[25] After obtaining supplies in Maui he went to Oahu, arriving in Honolulu,[26] where he met Francisco de Paula y Marín, who was appointed representative of the United Provinces of South America and captain of the armies.[27] He also recruited Peter Corney, who put in charge of the corvette Santa Rosa.[28] On 26 August he took charge of the Santa Rosa, which he had to rebuild partially. Six days later he arrived to Kauai island. There he captured those who had mutinied in the Santa Rosa, executed the leaders and punishing the rest with twelve blows with a lash in the face.[29] After buying food, ammunition and hiring eighty men, the fleet left, heading to California.

California and Central America

Bouchard sailed towards California to exploit the Spanish trade. However the Spanish authorities knew his intentions since on 6 October the Clarion had reported two corsair ships were ready to attack the Californian coast. The governor, Pablo Vicente de Solá, who resided in Monterey, ordered removed from the city all valuables and two thirds of the gunpowder stocked in the military outposts.[30]

On 20 November 1818, the watchman of Punta de Pinos, located at the tip of the southern end of Monterey Bay, sighted the two Argentine ships. The governor was informed; the Spanish prepared the cannons along the coastline, the garrison manned their battle stations, and the women, children, and men unfit to fight were sent to an inland mission at Soledad.[31]

Bouchard met with his officers to design the attack plan. Peter Corney knew the bay from two previous visits to Monterey. They used the corvette Santa Rosa to attack since the deep draft frigate La Argentina might run aground. The frigate had to be towed by small boats and out of range of the Spanish artillery. Once it was out of range, Bouchard sent captain Sheppard to the Santa Rosa, leading two hundred soldiers, carrying firearms and lances.[31]

Santa Rosa corvette, led by Sheppard, anchored by midnight near the Presidio of Monterey.[2] Since, after towing the frigate and rowing back to the corvette the men were very tired, Sheppard decided not to attack in the night. At dawn he discovered that he had anchored too close to the coast and that few meters ahead the Spanish artillery was ready to attack them. The captain opened fire, but after fifteen minutes of combat the corvette surrendered.[32]

From the frigate, Bouchard saw his men defeated, but also noticed that the Spanish lacked boats to seize Santa Rosa. The corsair ordered his ships to weigh anchor and move towards the port. However, due to the frigate's draft, he could not get close enough to open fire. After sunset they brought the corvette's survivors aboard the frigate. On 24 November, before dawn, Bouchard ordered his men to board the boats. They were 200: 130 had rifles and 70 had spears. They landed 7 km (4.3 mi) away from the fort in a hidden creek. The fort defended by José Bandini resisted ineffectively, and after an hour of combat the Argentine flag flew over it.[4] The Argentines took the city for six days, during which time they stole the cattle and burned the fort, the artillery headquarters, the governor's residence and the Spanish houses. The town's residents were unharmed.[33]

On 29 November they left Monterey, passed Point Conception, and anchored off of Refugio Canyon, about twenty miles west of Santa Barbara, where they went to the hacienda of the Ortega family rancho. Bouchard was told the family had strongly supported the Spanish cause. On 5 December the Argentines disembarked near the farm and, meeting no resistance, took all the food, killed the cattle, and slit the throats of the saddle horses in the corrals. A small squadron of cavalry, sent by José de la Guerra y Noriega from the Santa Barbara Presidio, waited quietly nearby for an opportunity to capture some stragglers. They captured an officer and two sailors, whom they brought back to the Presidio in chains. Bouchard waited for them the whole day, because he thought they were lost, until he decided to burn the farm and go to Mission Santa Barbara, where the three men could have been taken as prisoners. Once he arrived at Santa Bárbara, and seeing the town was heavily defended (in reality, what Bouchard saw through his spyglass was the same small troop of cavalry, which stopped and changed costume each time it passed behind a heavy clump of brush), the privateer sent a messenger to speak to the governor. After the negotiation the three captured men returned to the Santa Rosa and Bouchard freed one prisoner.[34]

On 16 December the ships weighed anchor and headed to San Juan Capistrano. There he requested food and ammunition; a Spanish officer said "he had enough gunpowder and cannonballs for me". Threats annoyed Bouchard; he sent one hundred men to take the town. After a short fight the corsairs took some valuables and burned the Spanish houses. On 20 December he left for Vizcaíno Bay, where he repaired the ships and allowed his men to rest.[35] Among the Spanish settlements in California the raids earned Bouchard a reputation as "California's only pirate" (and was therefore often referred to as Pirata Buchar by the Spanish colonists of the day).[36][37] To avoid an attack from Bouchard like the one he successfully launched against San Juan Capistrano, San Buenaventura moved all of its herd and valuables inland.[38]

On 17 January they sailed to the port of San Blas, located on the west coast of mainland Mexico, and began a blockade eight days later. During the approach, they seized the Spanish brig Las Ánimas, with a cargo of cacao. Near Tres Marías islands, La Argentina boarded the British Good Hope. After four days, they allowed the ship to weigh anchor, but not before confiscating her cargo of Spanish goods. On 1 March, while blockading San Blas, they sighted a schooner. The two ships began to chase her but failed to reach her. Afterwards, Bouchard ordered them to proceed south to Acapulco following the coastline. Once they arrived, he sent a boat with an officer to explore the place, and to report the quantity and quality of the ships in the harbour. The officer reported there was no relevant ship nearby, and Bouchard decided to sail on.[39]

On 18 March the Argentines went to a town called Sonsonate in El Salvador. An officer sent to spy on the port reported there were reasonable ships to board. On that day Bouchard captured a brigantine. On 2 April they arrived at the port of El Realejo, and prepared two boats with cannons and sixty men, led by Bouchard himself. They were sighted by the port's watch, however, and Spanish troops went to defend the ships. In addition, they had protected the port with four ships: a brig, two schooners and a lugger. After an intense combat three ships were taken. Bouchard burned the brig San Antonio and the schooner Lauretana, because their owners had not offered enough money for them, 30,000 and 20,000 duros respectively. Owing to their quality he kept the lugger, Neptuno, and the second schooner, María Sofía.[40]

After the combat in El Realejo, the Argentines found the same schooner with the Spanish flag that they had lost in San Blas. The ship went forward towards the Santa Rosa, whose crew was composed of inexpert Hawaiian sailors and had few artillery. A first attack killed three Argentines and wounded many more. When the Argentine ship was going to repel the enemy's boarding, the schooner took out the Spanish flag and showed it was a Chilean ship, called Chileno (Chilean). It was commanded by a corsair whose surname was Croll. Bouchard demanded that his surgeon heal the wounded, but the Chilean corsair decided to go away.[41]

On 3 April 1819 Hippolyte Bouchard's long expedition ended. He went to Valparaíso, in Chile in order to collaborate with José de San Martín's campaign to liberate Peru. Some historians, for example Miguel Ángel de Marco,[42] suggest that the flags of the United Provinces of Central America and most of the states that composed it were inspired by the Argentine Flag that Bouchard took with him. While others claim that the flag was modeled on the Argentine flag, but introduced by Commodore Louis-Michel Aury.

Arrest in Chile

On 9 July 1819, exactly two years after Bouchard left Buenos Aires, the Santa Rosa and the María Sofía arrived to Valparaíso. the 12th of the same month arrived the Neptuno and one day later arrived La Argentina. Bouchard was informed that Thomas Cochrane had ordered his arrest.[7] The corsair replied that the Chilean government had no authority to judge him and that he would only speak about his travels to the Argentine authority. The trial for piracy started on 20 July. In September a Chilean fleet had left to Peru to try to take El Callao fortress. In order to put pressure on the court, Argentine Colonel Mariano Necochea along with 30 Mounted Grenadiers and sailors stormed La Argentina and took control of the ship in the name of the United Provinces.[43] Then, the corsair's defense decided to accelerate the trial and the judge decided, on 9 December, to return all ships, papers and documents to Bouchard; however the money and the booty were not given back. The ships had no sails nor cannons, because they had been requested by the Chilean navy. Bouchard, virtually in bankruptcy, used a schooner to deliver clay to Buenos Aires, and due to the poor future of his ships, he decided to change the name of La Argentina to Consecuencia, the name she had before being taken. They were used as transport ships: the Consecuencia carried 500 soldiers to Peru, while Santa Rosa took cattle and weapons.

Later life

In 1820 Bouchard was in Peru serving with the Chilean navy. In December of that year he requested José de San Martín, who had been named Protector of Peru, to be allowed to return to Argentina due to his economic situation. San Martín ordered him to stay in Lima for four more months.[44]

When Lord Cochrane took the money stored in the warships he commanded to compensate for the wages he did not receive, San Martín decided to fight against him. He created the Peruvian Navy and Bouchard was given the frigate Prueba, captured by the Royalists in Callao.[45] Cochrane complained again and Tomás Guido asked him to protest to the Chilean government and ordered Bouchard to be ready to fight if the Scottish admiral decided to attack the Peruvian fleet. Bouchard confronted Cochrane at sea, to the point of challenging him to a single duel; however, the Chilean admiral refused to fight and sailed back to Valparaíso.[43]

After the incident, Bouchard continued to sail in Peruvian waters commanding the Santa Rosa, because Consecuencia had to be sold as firewood. Santa Rosa would end up being burned during the El Callao rebellion of 1824. Bouchard would also participate, in 1828, in the war against Gran Colombia. After the death of the Admiral Martín Jorge Guise, he was in charge of the Peruvian Navy, but he would retire one year later, after the loss of the ensign ship, Presidente.[46]

During his retirement Bouchard decided to live on the properties that had been given to him by the Peruvian Government, San Javier y San José de la Nazca, near Palpa. He established a sugar mill. Bouchard had lost contact with his family many years before: after the expedition with Brown he had lived with his wife for only ten months, and he never knew his younger daughter who was born after the beginning of his expedition around the world. He was killed by one of his servants on 4 January 1837.[5]

Legacy

In his adopted country of Argentina, Bouchard is revered as a patriot and several places (one being a street in downtown Buenos Aires close to the waterfront) are named in his honor.[2] USS Borie, an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer sold to Argentina in July 1972, was renamed as ARA Hipólito Bouchard; the ship saw action in the Falklands War.[47]

See also

- May Revolution

- Argentine War of Independence

- Spanish American wars of independence

- French Campaign in Egypt

- Napoleon

Notes

- ^ a b c The California State Military Museum gives 1783 as his birth date. Also, note that this website's form of the name - "de Bouchard" - does not agree with published sources.[2]

References

- ^ a b c Pigna 2005, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d "Hippolyte de Bouchard and His Attacks on the California Missions". Sacramento, CA: California State Military Museum – California State Military Department. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ a b Pérez Pardella 1997.

- ^ a b De Marco 2002, p. 180.

- ^ a b "Bouchard, Hipólito (1780–1837)" (in Spanish). IESE – Instituto Universitario del Ejército. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- ^ Prieto & Marí 1927, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Cerone, Pablo Martín (2004). "El Corsario Albiceleste" (in Spanish). Quinta Dimensión. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 124–125, 142–143.

- ^ Alonso Piñeiro 1984, ch. 33.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2016, pp. 59.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2016, pp. 68.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2016, pp. 92.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2016, pp. 109.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2016, pp. 124.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 160–161.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación.

- ^ Mercene, Manila men, p. 52.

- ^ Chapman 1921, pp. 442–443.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 168–170.

- ^ O'Donnell 1998.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2017, p. 122.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2017, p. 160.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Rossi Belgrano 2017, p. 182.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 172.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 177.

- ^ a b De Marco 2002, p. 178.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 179.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Tompkins 1975, pp. 16–17.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 183.

- ^ Yenne 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Jones 1997, p. 170.

- ^ "California's Only Pirate - Hippolyte de Bouchard".

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 185–187.

- ^ De Marco 2002, pp. 187–188.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 189.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 190.

- ^ a b Pigna 2005, p. 94.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 204.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 207.

- ^ De Marco 2002, p. 208.

- ^ "Destructor A.R.A. "Bouchard" D-26" (in Spanish). Histarmar. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Alonso Piñeiro, Armando (1984). La historia Argentina que muchos argentinos no conocen (in Spanish) (5th ed.). Buenos Aires: Depalma. ISBN 978-9501402025.

- Chapman, Charles Edward (1921). A History of California: The Spanish Period. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Cichero, Daniel E. (1999). El corsario del plata (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. ISBN 950-07-1560-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - De Marco, Miguel Ángel (2002). Corsarios Argentinos (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. ISBN 950-49-0944-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Departamento de Estudios Históricos Navales de la Armada Argentina (1987). Historia marítima Argentina (in Spanish). Vol. V. Buenos Aires: Cuántica Editora. ISBN 950-9257-05-2.

- Gregory, Kristiana (1995). The Stowaway: A Tale of California Pirates. Scholastic Trade. ISBN 0-590-48822-8.

- Jones, Roger W. (1997). California from the Conquistadores to the Legends of Laguna. Laguna Hills, CA: Rockledge Enterprises. ASIN B0006R3LVM.

- Leffingwell, Randy (2005). California Missions and Presidios. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press, Inc. ISBN 0-89658-492-5.

- Melzer, Michael (2016). The Patriot Pirate (1st ed.). California. ISBN 978-1-36-686692-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mitre, Bartolomé (1909). Páginas de Historia (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: La Nación.

- O'Donnell, Pacho (1998). El Aguila Guerrera: La Historia Argentina Que No Nos Contaron (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Editorial Sudamericana. ISBN 978-9500714617.

- Pérez Pardella, Agustín (1997). José de San Martín, El Libertador Cabalga (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Planeta. ISBN 978-9507428166.

- Pigna, Felipe (2005). Los mitos de la historia argentina (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Editora Argentina. ISBN 950-49-1342-3.

- Pitt, Leonard (1970). Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01637-8.

- Prieto, N.; Marí, A. (1927). Historia Completa de la Nación Argentina (in Spanish). Vol. XXIV. Buenos Aires.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rossi Belgrano, Alejandro and Mariana (2016). Nuevos Documentos sobre el Crucero de la Argentina a través del Mundo Vol I (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Buenos Aires. ISBN 978-987-42-0631-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rossi Belgrano, Alejandro and Mariana (2017). Nuevos Documentos sobre el Crucero de la Argentina a través del Archipiélago Hawaiano Vol II (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Buenos Aires. ISBN 978-987-42-3709-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tompkins, Walker A. (1975). Santa Barbara, Past and Present. Santa Barbara, CA: Tecolote Books. ASIN B0006XNLCU.

- Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. San Diego, CA: Advantage Publishers Group. ISBN 1-59223-319-8.

External links

- Hipólito (Hypolite) Bouchard and the Raid of 1818 at Monterey County Historical Society