Himalayas

| The Himalayas | |

|---|---|

The arc of the Himalayas showing the eight-thousanders (in red); Indo-Gangetic Plain; Tibetan plateau; rivers Indus, Ganges, and Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra; and the two anchors of the range (in yellow) | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Everest, Nepal/China |

| Elevation | 8,848.86 m (29,031.7 ft) |

| Coordinates | 27°59′N 86°55′E / 27.983°N 86.917°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,500 mi) |

| Area | 595,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

Map of the Himalayan-Hindu Kush region | |

| Countries | [a] |

| Continent | Asia |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Alpine orogeny |

| Rock age | Cretaceous to Cenozoic |

| Rock types | |

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (/ˌhɪməˈleɪ.ə, hɪˈmɑːləjə/ HIM-ə-LAY-ə, hih-MAH-lə-yə)[b] is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has several peaks exceeding an elevation of 8,000 m (26,000 ft) including Mount Everest, the highest mountain on Earth. The mountain range runs for 2,400 km (1,500 mi) as an arc from west-northwest to east-southeast at the northern end of the Indian subcontinent.

The Himalayas occupy an area of 595,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) across six countries–Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. The sovereignty of the range in the Kashmir region is disputed among India, Pakistan, and China. It is bordered by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges on the northwest, Tibetan Plateau in the north, and by the Indo-Gangetic Plain in the south. Its western anchor Nanga Parbat lies south of the northernmost bend of the Indus river and its eastern anchor Namcha Barwa lies to the west of the great bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. The Himalayas consists of four parallel mountain ranges: the Sivalik Hills on the south; the Lower Himalayas; the Great Himalayas, which is the highest and central range; and the Tibetan Himalayas on the north. The range varies in width from 350 km (220 mi) in the north-west to 150 km (93 mi) in the south-east.

The Himalayan range is one of the youngest mountain ranges on Earth and is made up of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. It was formed more than 10 mya due to the subduction of the Indian tectonic plate with the Eurasian Plate along the convergent boundary. Due to the continuous movement of the Indian plate, the Himalayas keep rising every year, making them geologically and seismically active. The mountains consist of large glaciers, which are remnants of the last ice age, and give rise to some of the world's major rivers such as the Indus, Ganges, and Tsangpo–Brahmaputra. Their combined drainage basin is home to nearly 600 million people including 52.8 million living in the vicinity of the Himalayas. The region is also home to many endorheic lakes.

The Himalayas have a major impact on the climate of the Indian subcontinent. It blocks the cold winds from Central Asia, and plays a significant roles in influencing the monsoons. The vast size, varying altitude range, and complex topography of the Himalayas result in a wide range of climates, from humid and subtropical to cold and dry desert conditions. The mountains have profoundly shaped the cultures of South Asia and Tibet. Many Himalayan peaks are considered sacred across various Indian and Tibetan religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon. Hence, the summits of several peaks in the region such as Gangkhar Puensum, Machapuchare, and Kailash have been off-limits to climbers.

Etymology

The name of the range is derived from the Sanskrit word Himālaya (हिमालय) meaning 'abode of snow'.[4][5][6] It is a combination of the words hima (हिम) meaning 'frost/cold' and ālaya (आलय) meaning 'dwelling/house'.[7][8] The name of the range is mentioned as Himavat (Sanskrit: हिमवत्) in older literature such as the Indian epic Mahabharata, which is the personification of the Hindu deity Himavan.[9] The mountain range is known as Himālaya in Hindi and Nepali (both written हिमालय),[10] Himalaya (ཧི་མ་ལ་ཡ་) in Tibetan,[11] Himāliya (سلسلہ کوہ ہمالیہ) in Urdu,[12] Himaloy (হিমালয়) in Bengali,[13] and Ximalaya (simplified Chinese: 喜马拉雅; traditional Chinese: 喜馬拉雅; pinyin: Xǐmǎlāyǎ) in Chinese.[14] It was mentioned as Himmaleh in western literature such as Emily Dickinson's poetry and Henry David Thoreau's essays.[15][16]

Geography and topography

The Himalayas run as an arc for 2,400 km (1,500 mi) from west-northwest to east-southeast at the northern end of the Indian subcontinent, separating the Indo-Gangetic Plains from the Tibetan Plateau. It is bordered by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges on the northwest, which extend into Central Asia.[1][17] Its western anchor Nanga Parbat lies south of the northernmost bend of the Indus river in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and its eastern anchor Namcha Barwa lies to the west of the great eastern bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet Autonomous Region of China. The Himalayas occupies an area of 595,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) across six countries – Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. The sovereignty of the range in the Kashmir region is disputed amongst India, Pakistan, and China. The range varies in width from 350 km (220 mi) in the north-west to 150 km (93 mi) in the south-east.[1][18] The range has several peaks exceeding an elevation of 8,000 m (26,000 ft) including Mount Everest, the highest mountain on Earth at 8,848 m (29,029 ft).[19]

Sub-ranges

The Himalayas consist of four parallel mountain ranges from south to north: the Sivalik Hills on the south; the Lower Himalayas; the Great Himalayas, which is the highest and central range; and the Tibetan Himalayas on the north.[20][21]

The Sivalik Hills form the lowest sub-Himalayan range and extends for about 1,600 km (990 mi) from the Teesta River in the Indian state of Sikkim to northern Pakistan. The name derives from Sanskrit meaning "Belonging to Shiva", which was originally used to denote the 320 km (200 mi) stretch from Haridwar to the Beas River. The range is about 16 km (9.9 mi) wide on average and the elevation ranges from 900–1,200 m (3,000–3,900 ft). It rises along the Indo-Gangetic Plain and is often separated from the higher northern sub-ranges by valleys. The eastern portion of the range is called Churia Range in Nepal.[22][23]

The Lower or Lesser Himalaya (also known as Himachal) is the lower middle sub-section of the Himalayas. It extends almost along the entire length of the Himalayas and is about 75 km (47 mi) wide. It is mostly composed of rocky surfaces and has an average elevation of 3,700–4,500 m (12,100–14,800 ft).[22][24] The Greater Himalayas (also known as Himadri) form the highest section of the Himalayas and extend for about 2,300 km (1,400 mi) from northern Pakistan to northern Arunachal Pradesh in India. The sub-range has an average elevation of more than 6,100 m (20,000 ft) and contains many of the world's tallest peaks, including Everest. It is mainly composed of granite rocks.[22][25] The Tibetan Himalayas (also known as Tethys) form the northern most sub-range of the Himalayas in Tibet.[21][26]

Divisions

Longitudinally, the range is broadly divided into three regions–western, central, and eastern.[27] The Western Himalayas form the westernmost section of the range and extend for about 560 km (350 mi) from the bend of the Indus River along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region in the north-west to the Satlej river basin in India in the south-east. Most of the region lies in the Kashmir territory disputed between India and Pakistan with certain portions of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The Indus forms the division between the Western Himalayas and the Karakoram range to the north. The Western Himalayas include the Zanskar, Pir Panjal Ranges, and parts of the Sivalik and Great Himalayas. The western anchor Nanga Parbat is the highest point in the region at 8,126 m (26,660 ft).[28] It is also referred Punjab, Kashmir or Himachal Himalyas from west to east locally.[27][29]

The central Himalayas or Kumaon extend for about 320 km (200 mi) along the state of Uttarakhand in northern India from the Sutlej River in the east to the Kali River in the west. The region comprises parts of Sivalik and Great Himalayas. At lower elevations below 2,400 m (7,900 ft), the region has a temperate climate and consists of permanent settlements. At elevations higher than 4,300 m (14,100 ft), permanent snow caps cover the Great Himalayas with the highest peaks being Nanda Devi at 7,817 m (25,646 ft) and Kamet at 7,756 m (25,446 ft). The region is also the source of major streams of the Ganges river system.[30]

The Eastern Himalayas form the eastern most stretch of the range and consist of the states of parts of Tibet in China, Sikkim, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, parts of other North East Indian states and north West Bengal in India, entirety of Bhutan, mountain regions of central and eastern Nepal, and most of the western lowlands in Nepal.[31] The eastern Himalayas broadly consists of two regions–the western Nepal Himalayas and the eastern Assam Himalayas.[1][29] The Nepal Himalayas forms the centre of the Himalayan curve and extend for 800 km (500 mi) between the Kali and Teesta Rivers. The Great Himalayas in the region form the highest part of the entire Himalayas and consist of many of the eight-thousanders including Everest, Kanchenjunga at 8,586 m (28,169 ft), and Makalu at 8,463 m (27,766 ft). These mountains host large glaciers that form the source of various rivers of the Ganges-Brahmaputra river system. The high altitude regions are uninhabitable with few mountain passes inbetween that serve as crossovers with the human settlements in the lower valleys.[32]

The Assam Himalaya forms the eastern most sub-section that extends eastward for 720 km (450 mi) from the Indian state of Sikkim through Bhutan and north-east India past the Dihang River to the India-Tibet border. The highest peak is the eastern anchor Namcha Barwa at 7,756 m (25,446 ft). The region is the source of many of the tributaries of the Brahmaputra River and consists of major mountain passes such as Nathu La, and Jelep La.[33] Beyond the Dihang valley, the mountains extend as Purvanchal mountain range across the eastern boundary of India.[29]

Geology

The Himalayan range is one of the youngest mountain ranges on the planet and consists of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rock. According to the modern theory of plate tectonics, it was formed as a result of a continental collision and orogeny along the convergent boundary between the India and Eurasian Plates. During the Jurassic period (201 to 145 mya), the Tethys Ocean formed the southern border of then existent Eurasian landmass. When the super-continent Gondwana broke up nearly 180 mya, the Indo-Australian plate slowly drifted northwards towards Eurasia for 130–140 million years.[34] The Indian Plate broke up with the Australian Plate about 100 mya.[35] The Tethys ocean constricted as the Indian plate moved gradually upward. As both the plates were made of continental crusts, which were less dense than oceanic crusts, the increased compressive forces resulted in folding of the underlying rock bed.[36] The thrust faults created between the folds resulted in granite and basalt rocks from the Earth's mantle protruding through the crust. During the paleogene period (about 50 mya), the Indian plate collided with the Eurasian plate after it completely closed the Tethys ocean gap.[34][37]

The Indian plate continued to subduct under the Eurasian plate over the next 30 million years that resulted in the formation of the Tibetan plateau. During miocene (20 mya), the increasing collision between the plates resulted in the top layer of metamorphic rocks getting peeled, which moved southwards to form nappes with trenches in between. As the mountains received rainfall, the waters flowing down the mountains eroded and steepened the southern slopes. The silt deposited by these rivers and streams in the trough between the Himalayas and the Deccan plateau formed the Indo-Gangetic Plain. About 0.6 mya in the pleistocene period, the Himalayas rose higher and became the highest mountains on Earth. In the northern Great Himalayas, new gneiss and granite formations emerged on crystalline rocks that gave rise to the higher peaks.[34][38]

The summit of Mount Everest is made of unmetamorphosed marine ordovician limestone with fossil trilobites, crinoids, and ostracods from the Tethys ocean.[39] The upliftment of the Himalayas occurred gradually and as the Great Himalayas became higher, they became a climatic barrier and blocked the winds, which resulted in lesser precipitation on the upper slopes. The lower slopes continued to be eroded by the rivers, which flowed in the gaps between the mountains and the folded lower Shivalik Hills and the Lesser Himalayas were formed due to the downwarping of the intermediate lands. Minor streams ran between the faults within the mountains until they joined the major river systems in the plains. Intermediate valleys such as Kashmir and Kathmandu were formed from temporary lakes that were formed during pleistocene, which dried up later.[34][40]

The Himalayan region is made up of five geological zones– the Sub-Himalayan Zone bound by the Main Frontal Thrust and the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT); the Lesser Himalayan Zone between the MBT and the Main Central Thrust (MCT); the Higher Himalayan Zone beyond the MCT; the Tethyan Zone, separated by the South Tibetan Detachment System; and the Indus-Tsangpo Suture Zone, where the Indian plate is subducted below the Asian plate.[41] The Arakan Yoma highlands in Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal were also formed as a result of the same tectonic processes that formed the Himalayas.[42] The Indian plate continues to be driven horizontally at the Tibetan Plateau at about 67 mm (2.6 in) per year, forcing it to continue to move upwards. About 20 mm (0.79 in) per year is absorbed by thrusting along the Himalaya southern front, which leads to the Himalayas rising by about 5 mm (0.20 in) per year.[43] This makes the Himalayan region geologically active and the movement of the Indian plate into the Asian plate makes the region seismically active, leading to earthquakes from time to time.[44][45]

The northern slopes of the Himalayas have a thicker soil cover than the southern slopes due to the lesser number of rivers and streams. These soils are loamy and are dark brown in colour, and are covered with forests in the lowlands and grassland meadows in the mid altitudes. The composition and texture of the soils in the Himalayas also vary across regions. In the Eastern Himalayas, the wet soils have a high humus content conducive for growing tea. Podzolic soils occur in the eastern range of the Indus basin between the Indus and Shyok Rivers. The Ladakh region is generally dry with saline soil while fertile alluvial soils occur in select river valleys such as the Kashmir valley. The higher elevations consist of rock fragments and lithosols with very low humus content.[34]

Hydrology

Glaciers

The Himalayas and the Central Asian mountain ranges consist of the third-largest deposit of ice and snow in the world, after the Antarctic and Arctic regions.[46] It is often referred to as the "Third Pole" as it encompasses about 15,000 glaciers, which store about 12,000 km3 (2,900 cu mi) of fresh water.[47][48] The South Col and Khumbu Glacier in the Mount Everest region are amongst the world's highest glaciers.[49] The Gangotri which is 32 km (20 mi) long and is one of the largest glaciers, is one of the sources of the Ganges. The Himalayan glaciers show considerable variation in the rate of descent. The Khumbu moves about 1 ft (0.30 m) daily compared to certain other glaciers which move about 6 ft (1.8 m) per day.[50]

During the last ice age, there was a connected ice stream of glaciers between Kangchenjunga in the east and Nanga Parbat in the west.[51] The glaciers joined with the ice stream network in the Karakoram in the west, the Tibetan inland ice in the north, and came to an end below an elevation of 1,000–2,000 m (3,300–6,600 ft) in the south. While the current valley glaciers of the Himalaya reach at most 20–32 km (12–20 mi) in length, several of the main valley glaciers were 60–112 km (37–70 mi) long during the ice age.[52][53] The glacier snowline (the altitude where accumulation and ablation of a glacier are balanced) was about 1,400–1,660 m (4,590–5,450 ft) lower than it is today. Thus, the climate would have been at least 7.0–8.3 °C (12.6–14.9 °F) colder than it is today.[54]

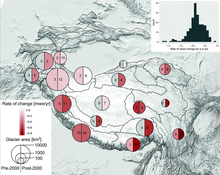

Since the late 20th century, scientists have reported a notable increase in the rate of glacier retreat across the region as a result of climate change.[55][56] The rate of retreat varies across regions depending on the local conditions. Since 1975, a marked increase in the loss of glacial mass from 5–13 Gt/yr to 16–24 Gt/yr has been observed with an estimated 13% overall decrease in glacial coverage in the Himalayas.[47][57][58][59] The resulting climate variations and changes in hydrology could affect the livelihoods of the people in the Himalayas and the plains below.[60]

Rivers

Despite its greater size, the Himalayas does not form a water divide across its span because of the multiple river systems that cut across the range. While the mountains were formed gradually, the rivers concurrently cut across deeper gorges ranging from 1,500–5,000 m (4,900–16,400 ft) in depth and 10–50 km (6.2–31.1 mi) in width. The actual water divide lies to the north of the Himalayas with rivers flowing down both the sides of the mountains. Some of the major river systems and their drainage system outdate the formation of the mountains itself. The water divide is formed by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges on the west and the Ladakh Range on the east, separating the Indus system from Central Asia. On the east, Kailas and Nyenchen Tanglha Mountains separate the Brahmaputra river system from the Tibetan rivers to the north. There are 19 major rivers in the Himalayas which form part of the two major river systems of Ganges-Brahmaputra, which follow an easterly course and Indus, which follows a north-westerly course.[50]

- The Indus Basin extends from the western section of the range and has a catchment area of nearly 450,000 km2 (170,000 sq mi). The river rises near Lake Manasarovar in Tibet and flows westward joining the Zanskar and Shyok Rivers. The five major tributaries of Indus–Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej join the Indus in the Punjab region spread across India and Pakistan. These five rivers constitute a watershed area of about 132,000 km2 (51,000 sq mi). The river system drains across the Himalayan region in Kashmir, before spreading through the Punjab Plains and later forms the Indus Delta near the India-Pakistan border before joining the Arabian sea.[61][62]

- The Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin extends from the north-eastern part of the Himalayas till its eastern edge. The system has an average discharge of 30,770 m2 (331,200 sq ft), which is the third greatest of the world's river systems and forms the largest alluvial deposits in the world with nearly 1.84 billion tonnes of silt deposited every year. The Ganges is formed by five head streams of which the major ones are the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi arising at Gangotri in Uttarakhand.[63] Other Himalayan rivers that form the major tributaries of the Ganges include Yamuna, Ramganga, Ghaghara, Rapti, Gandaki, Bagmati, and Kosi, which together drain about 218,000 km2 (84,000 sq mi) of area. The Brahmaputra arises in the Tibetan region flowing eastwards before making a turn towards south into India. The Teesta, Raidak, Manas form the major tributaries of the Brahmaputra and together drain 184,000 km2 (71,000 sq mi) of catchment area.[50][64] The Ganges and Brahmaputra join together before forming the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta spread across India and Bangladesh for nearly 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) is the largest in the world.[65]

The northern slopes of Gyala Peri and the peaks beyond the Tsangpo drain into the Irrawaddy River, which originates in eastern Tibet and flows south through Myanmar to drain into the Andaman Sea. The Salween, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers all originate from parts of the Tibetan Plateau, north of the great water divide. These are considered distinct from the Himalayan watershed and are known as circum-Himalayan rivers.[66]

Lakes

The Himalayan region has multiple lakes across various elevations including endorheic freshwater and saline lakes. The geology of the lakes vary across geographies depending on various factors such as altitude, climate, water source, and lithology. Tarns are high altitude mountain lakes situated above 5,500 m (18,000 ft) and are formed primarily by the snow-melt of the glaciers. The lower altitude lakes are replenished by a combination of rains, underground springs, and streams. Large lakes in the Himalayan basin were formed in the holocene period, when water pooled in the faults and the water supply was subsequently cut off.[67][68]

There are more than 4500 high altitude lakes of which about 12 large lakes contribute to more than 75% of the total lake area in the Indian Himalayas.[67] Pangong Lake spread across India and China is the highest saline lake in the world at an altitude of 4,350 m (14,270 ft) and amongst the largest in the region with a surface area of 700 km2 (270 sq mi).[69] Spread across 189 km2 (73 sq mi), Wular Lake is amongst the largest fresh water lakes in Asia.[70] Other large lakes include Tso Moriri, and Tso Kar in Ladakh, Nilnag, and Tarsar Lake, in Jammu and Kashmir, Gurudongmar, Chholhamu, and Tsomgo Lakes in Sikkim, Tilicho, Rara, Phoksundo, and Gokyo Lakes in Nepal.[67][71][72] Some of the Himalayan lakes present the danger of a glacial lake outburst flood as they have grown considerably over the last 50 years due to glacial melting.[73] While these lakes support a range of ecosystems and local communities, many of them remain poorly studied in terms of their hydrology and biodiversity.[67][74]

Climate

Due to its location and size, the Himalayas acts as a climatic barrier which affects the weather conditions of the Indian subcontinent and the regions north of the range.[75] The mountains are spread across more than eight degrees of latitude and hence includes a wide range of climatic zones including sub-tropical, temperate, and semi-arid. The climate in a region is determined by factors such as altitude, latitude, and the impact on monsoon.[76] There are generally five seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn or post-monsoon, winter, and spring.[77] The summer in April-May is followed by monsoon rains from June to September. The post monsoon season is largely devoid of rain and snow before beginning of cold winters in December-January with intermediate spring before the summer.[75] There are localised wind pressure systems at high altitudes resulting in heavy winds.[78]

Temperature

Due to its high altitude, the range blocks the flow of cold winds from the north into the Indian subcontinent.[75][79] This causes the tropical zone to extend farther north in South Asia than anywhere else in the world. The temperatures are more pronounced in the Brahmaputra valley in the eastern section as it lies at a lower latitude and due to the latent heat of the forced air from the Bay of Bengal which condenses before moving past the Namcha Barwa, the eastern anchor of the Himalayas.[80][76] Due to this, the permanent snow line is among the highest in the world, at typically around 5,500 m (18,000 ft) while several equatorial mountains such as in New Guinea, the Rwenzoris, and Colombia, have a snow line at 900 m (3,000 ft) lower.[81][82]

As the physical features of mountains are irregular, with broken jagged contours, there can be wide variations in temperature over short distances. The temperature at a location is dependent on the season, orientation and bearing with respect to the Sun, and the mass of the mountain. As the Sun is the major contributor to the temperature, it is often directly proportional to the received radiation from the Sun with faces receiving more sunlight having a higher heat buildup. In narrow valleys between steep mountain faces, the weather conditions may differ significantly on both the margins. The mountains act as heat islands and heavier mountains absorb and retain more heat than the surroundings, and therefore influences the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature from the winter minimum to the summer maximum.[83] However, soil temperatures mostly remain the same on both the sides of a mountain at altitudes higher than 4,500 m (14,800 ft).[84]

Temperatures in the Himalayas reduce by 2 °C (3.6 °F) for every 300 m (980 ft) increase of altitude.[76][85] Higher altitudes invariably experience low temperatures. In the Eastern Himalayas, Darjeeling at an altitude of 1,945 m (6,381 ft) has an average minimum temperature of 11 °C (52 °F) during the month of May, while the same has been recorded as −22 °C (−8 °F) at an altitude of 5,000 m (16,000 ft) on the Everest. At lower altitudes, the temperature is pleasantly warm during the summers. During winters, the low-pressure weather systems from the west cause heavy snowfall.[75]

Precipitation

There are two periods of precipitation with most of the rainfall occurring during the post summer season and moderate amount during the winter storms.[75] The Himalayan range obstructs the path of the south west monsoon winds, causing heavy precipitation on the slopes and the plains below.[79] The effect of Himalayas on the hydroclimate impacts millions in the plains as the variability in monsoon rainfall is the main factor behind wet and dry years.[86] As the Himalayas force the monsoon winds to give up most of the moisture before ascending up, the winds became dry once its reaches the north of the mountains. This results in the dry and windy cold desert climate in the Tibetan Himalayas and the plateau beyond.[75] It also played a role in the formation of Central Asian deserts such as the Taklamakan and Gobi.[87]

The monsoon is triggered by the different rates of heating and cooling between the Indian Ocean and Central Asia, which create large differences in the atmospheric pressure prevailing above each. As the Central Asian landmass heats up during the summer compared to the ocean below, the difference in pressure creates a thermal low. The moist air from the ocean is pushed inwards towards the low pressure system causing the monsoon winds. It results in precipitation along the slopes due to the orographic effect as the air rises along the mountains and condenses.[78][88] The monsoon begins at the end of May in the eastern fringes of the range and moves upwards towards the west in June and July. There is heavy precipitation in the east which reduces progressively towards the west as the air becomes drier. Cherrapunji in Eastern Himalayas is one of the wettest places on Earth with an annual precipitation of 428 in (10,900 mm).[89]

The average annual rainfall varies from 120 in (3,000 mm) in the Eastern Himalayas to about 120 in (3,000 mm) in the Kumaon region. The northern extremes of the Great Himalayas in Kashmir and Ladakh receive only 3–6 in (76–152 mm) of rainfall per year.[75] During the winter season, a high pressure system develops over Central Asia, which results in winds flowing towards the Himalayas. However, due to the presence of less water bodies in the Central Asian region, the moisture content is low.[78] As the condensation occurs at higher altitudes in the north, there is more precipitation in the Great Himalayas in the west during the winter rains and the precipitation reduces towards the east. In January, the Kumaon region receives about 3 in (76 mm) of rainfall compared to about 1 in (25 mm) in the Eastern Himalayas.[75]

Climate change

The Himalayan region has a highly sensitive ecosystem and is amongst the most affected regions due to climate change. Since the late 20th century, scientists have reported a notable increase in the rate of glacier retreat and changes occurring at a far rapid rate.[55][56][90] As per a 2019 assessment, the Himalayan region, which had experienced a temperature rise of 0.1 °C (32.2 °F) per decade was warming at an increased rate of 0.1 °C (32.2 °F) per decade over the past half a century. The average warm days and nights had also increased by 1.2 days and 1.7 nights per decade while the average cold days and nights had declined by 0.5 and 1 respectively. This has also prolonged the length of the growing season by 4.25 days per decade.[91]

The climate change might results in erratic rainfall, varying temperatures, and natural disasters like landslides, and floods.[92][93] The increasing glacier melt had been followed by an increase in the number of glacial lakes, some of which may be prone to dangerous floods. The region is expected to encounter continued increase in average annual temperature and 81% of the region's permafrost is projected to be lost by the end of the century.[94] The increased warming and melting of snow is projected to accelerate the regional river flows until 2060 after which it would decline due to reduction in ice caps and glacier mass. As the precipitation is projected to increase concurrently, the annual river flows would be largely unaffected for the Eastern Himalayan rivers fed by monsoons, but would reduce the flows in the Western Himalayan rivers.[95][96][97]

Almost a billion people live on either side of the mountain and are prone to impact of the climate change. This includes the people who live in the mountains, who are more vulnerable due to temperature variations and other biota.[90] Countries in the Himalayan region including Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan are amongst the most vulnerable countries in the Global South due to climate change.[98][99][100] The temperature rise increases the incidence of tropical diseases such as malaria, and dengue further north. The extreme weather events might cause physical harm directly and indirectly due to lack of access and contamination of drinking water, pollution, exposure to chemicals, and destruction of crops, and drought.[101][102][103] The climate change also impact the flora and fauna of the region. Changes might decrease the territory available for local wildlife and reduction in prey for the predators. This puts the animals in conflict with humans as humans might encroach animal territories and the animals might venture into human habitats for search of food, which might exacerbate the economic loss of the local population.[104]

The Himalayan nations are signatories of the Paris agreement, aimed at climate change mitigation and adaptation.[105][106] The actions are aimed at reducing emissions, increase the usage of renewable energy, and sustainable environmental practices.[107] As the local population increasingly experience the impact of the changes in climate such as variations in temperature and precipitation, and change in vegetation, they are forced to adapt for the same. This has led to increased awareness on the impact of climate change, and adaptations such as change in crop cycles, introduction of drought resistant crops, and plantation of new trees.[108] This has also led to the construction of more dams, canals, and other water structures, to prevent flooding and aid in agriculture. New plantations on barren lands to prevent landslides, and construction of fire lines made of litter and mud to prevent forest fires have been undertaken.[109][110] However, lack of funding, awareness, access to technology, and government policy are barriers for the same.[109]

Flora and fauna

The Himalayan region belongs to the Indomalayan realm.[111] The flora and fauna of the Himalayas vary broadly across regions depending on the climate and geology.[72] The Himalayas are home to multiple biodiversity hotspots, and is home to an estimated 35,000+ species of plants and 200+ species of animals. An average of 35 new species have been found every year since 1998.[112]

Flora

There are four types of vegetation found in the region tropical and subtropical, temperate, coniferous, and grasslands. Tropical and subtropical broadleaf forests are mostly constricted to the high temperature and humid regions in Eastern and Central Himalayas, and pockets of Kashmir in the west. There are about 4,000 species of Angiosperms with major vegetation include Dipterocarpus, and Ceylon ironwood on porous soils at elevations below 2,400 m (7,900 ft) and oak, and Indian horse chestnut on lithosol between 1,100–1,700 m (3,600–5,600 ft). Himalayan subtropical pine forests with Himalayan screw pine trees occur above 4,000 m (13,000 ft) and Alder, and bamboo are found on terrains with higher gradient. Temperate forest occur at altitudes between 1,400–3,400 m (4,600–11,200 ft) while moving from south-east to north-west towards higher latitude. Eastern and Western Himalayan broadleaf forests consisting of sal trees dominate the ecosystem.[113]

At higher altitudes, Eastern and Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests consisting of various conifers occur. Chir pine is the dominant species which occurs at elevations from 800–900 m (2,600–3,000 ft). Other species include Deodar cedar, which grows at altitudes of 1,900–2,700 m (6,200–8,900 ft), blue pine and morinda spruce between 2,200–3,000 m (7,200–9,800 ft). At higher altitudes, alpine shrubs and meadows occur above the trees. The Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows extend between 3,200–4,200 m (10,500–13,800 ft) and the Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows occur at altitudes of 3,600–4,500 m (11,800–14,800 ft). Major vegetation include Juniperus, Rhododendron on rocky terrain facing the Sun, various flowering plants at high elevations, and mosses, and lichens in humid, shaded areas.[113][114]

Interspersed Grasslands occur at certain regions, with thorns and semi-desert vegetation at low precipitation areas in the Western Himalayas.[113] The high altitude mountainous areas are mostly barren or, at the most, sparsely sprinkled with stunted bushes.[74] The Himalayas are home to various medicinal plants such as Abies pindrow used to treat bronchitis, Andrachne cordifolia used for snake bites, and Callicarpa arborea used for skin diseases. Nearly a fifth of the plant species in the Himalayas are used for medicinal purposes.[115][116] Climate change, illegal deforestation, and introduction of non native species have had an effect on the flora of the range. The increase in temperature has resulted in shifting of various species to higher elevations, and early flowering and fruiting.[117]

Fauna

Many of the animal species are from the tropics, which have adapted to the various conditions across the Himalayan range. Some of the species of the Eastern Himalayas are similar to those found in East and South East Asia, while the animals of the Western Himalayas has characteristics of species from Central Asia and Mediterranean region. Fossils of species such as giraffe, and hippopotamus have been found in the foothills, suggesting the presence of African species some time ago. Large mammals such as Indian elephant, and Indian rhinoceros are confined to the densely forested moist ecosystems in the Eastern and Central Himalayas. Many of the animal species found in the region are unique and endemic or nearly endemic to the region.[118]

Other large animal species found in the Himalayas include Asiatic black bear, clouded leopard, and herbivores such as bharal, Himalayan tahr, takin, Himalayan serow, Himalayan musk deer, and Himalayan goral. Animals found at higher altitudes include brown bear, and the elusive snow leopard, which mainly feed on bharal. The red panda is found in the mixed deciduous and conifer forests of the Eastern Himalayas and the Himalayan water shrew are found on the river banks. The forests of the foothills are inhabited by several different primates, including the endangered Gee's golden langur and the Kashmir gray langur, within highly restricted ranges in the east and west of the Himalayas, respectively. The yaks are large domesticated cattle found in the region.[74][118]

More than 800 species of birds have been recorded with a large number of species restricted to the Eastern Himalayas. Amongst the bird species found include magpies such as black-rumped magpie and blue magpie, titmice, choughs, whistling thrushes, and redstarts. Raptors include bearded vulture, black-eared kite, and Himalayan griffon. Snow partridge and Cornish chough are found at altitudes above 5,700 m (18,700 ft).[118] The Himalayan lakes also serve as breeding grounds for species such as black-necked crane and bar-headed goose.[67] There are multiple species of reptiles including Japalura lizards, blind snakes, and insects such as butterflies. Several fresh water fish such as Glyptothorax are found in the Himalayan waters. The extremes of high altitude favor the presence of extremophile organisms, which include various species of insects such as spiders, and mites.[118][119]

Conservation

The Himalayan fauna include endemic plants and animals and critically endangered or endangered species such as Indian elephant, Indian rhinoceros, musk deer and hangul.[118] There are more than 7,000 endemic plants and 1.9% of global endemic vertebrates in the region. As of 2022, there are 575 protected areas established by the nations in the Himalayan-Hindu Kush region, which account for 40% of the land area and 8.5% of the global protected area. There are also four biodiversity hotspots, 12 ecoregions, 348 key biodiversity areas, and six UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the region.[120][121]

Demographics

The Himalayan region with the associated Indo-Gangetic Plain and Tibetan plateau is home to more than a billion people.[90] In 2011, the population in the Himalayan region was estimated to be about 52.8 million with the combined drainage basin of the Himalayan rivers home to nearly 600 million.[122][123] Of this, 7.96 million (15.1% of the total Himalayan population) live in Eastern Himalayas, 19.22 million in Central Himalayas (36.4%), and 25.59 million reside in Western Himalayas (48.5%). The population of the Himalayas has grown considerably over the last five decades from 19.9 million in 1961 with the annual growth rate (3.31%) more than three times higher than the world average (1.1%) during the same period.[122]

The earliest tribes in the Himalayas might have originated from Dravidian people from the south of the Indian subcontinent as evidenced by the presence of Dravidian languages. The major human migration towards the Himalayan region occurred in 2000 BCE when Aryans came from Central Asia and progressively settled along the plains to the south. Information on the Aryan culture in the region is found in Hindu literature such as the Vedas, and Puranas. Since the second century BCE, the Silk Road in China was connected to the Indian subcontinent by various routes running along the Himalayan region. The northern side of the Himalayas was under the influence of various Tibetan kingdoms across history. In the Middle Ages, the southern side came under the influence of various Rajput kings and later under the Mughal rule. Nepal was ruled by various kingdoms from both the Indian and Tibetan regions, until it was conquered by the Gurkha kingdom in the early 18th century. Most of the southern region came under the British influence in the 18th century till the independence of the constituent states in the mid 20th century.[124]

Ethnicity and languages

The long history along with various outside influences have resulted in the mixture of various traditions and existence of wide range of ethnicity in the region. People speak various languages belonging to four principal language families–Indo-European, Tibeto-Burman, Austroasiatic, and Dravidian, with the majority of the languages belonging to the first two categories. The Tibetan Himalayas are inhabited by Tibetan people, who speak Tibeto-Burman languages. The Great Himalayas are mostly inhabited by nomadic groups and tribes, with most of the population in Lesser Himalayas, and Shivalik Hills. People towards the Great Himalayas in the north parts mostly speak Tibeto-Burman, while populations in the lower ranges on the southern slopes speak Indo-European languages.[125]

The inhabitants of the Western Himalayas include the Kashmiri people, who speak Kashmiri in the Vale of Kashmir and the Gujjar and Gaddi people, who speak Gujari and Gaddi respectively in the lower altitudes of Jammu and Himachal Pradesh in India. The last two are pastoral and nomadic people, who own flocks of cattle and migrate across the slopes based on seasons. Various ethnic people such as Ladakhi, Balti, and Dard live on the north of the Great Himalayas along the Indus basin in the Kashmir and Ladakh regions spread across India, Pakistan, and China. The Dard speak Dard, which is part of Indo-European languages, while the Balti and Ladakhi people speak Balti, and Ladakhi, which are part of Tibeto-Burman. In the Kumaon region in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand in India, Indo-European speakers such as the Kanet and Khasi reside in the lower altitudes along with descendants of migrants from Tibet, who speak Tibeto-Burman languages, in the Kalpa and Lahul-Spiti regions.[125][126]

In the Central Himalayas in Nepal, the Pahari people, who speak an Indo-European language Pahari, form the majority. People of various ethnicity such as Newar, Tamang, Gurung, Magar, Sherpa, Bhutia, Lepcha, and Kirat, who speak Tibeto-Burman languages, are spread across the mountainous regions of Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of North East India. The Newar and Kirat peoples are largely from the Kathmandu valley, and the Magars and Tamangs are spread across the region. The Gurung and Sherpa peoples live along the slopes of Annapurna and Everest respectively. The Lepcha people reside in Sikkim and western Bhutan while the Bhutia are found in eastern Bhutan. The Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh along the eastern edge is home to various Tibeto-Burman speaking ethnic groups such as Abor, Aka, Apatani, Dafla, Khamti, Khowa, Mishmi, Momba, Miri, and Singpho, who mostly practice shifting cultivation.[125][126]

Culture and religion

Himalayas have had a profound impact on the culture of the people in the region. The Himalayan region is occupied by people of various religions and several places in the Himalayas are of religious significance in, Bon, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Jainism, and Sikhism. Hindus form the majority of the low highlands and plains in Northern India and Nepal. People in high altitude region of Ladakh, Bhutan, and North East India follow Buddhism while Islam is dominant in the western region of the Himalayas and the Kashmir valley. Tibetan religions are followed in the northern Himalayas and various ethnicities in North East India follow indigenous religions.[126]

For the Hindus, Himalaya is a personification Himavat, the king of all mountains and the father of goddess Parvati.[127] It is also considered to be the birthplace of goddess Ganga, the personification of river Ganges.[128] It is considered as one of the 68 places hosting a Svayambhu form of Lingam, a form of Shiva. Himalaya is mentioned as the source of medicinal plants in Ayurveda, and is the name of the one of the 84 asanas in Siddha yoga.[129] Major Hindu pilgrimage centers include the Chota Char Dham–Gangotri, Yamunotri, Badrinath, and Kedarnath.[130][131] Thousands trek to the Amarnath Temple in Sind Valley, where an ice stalagmite formation in the Amarnath Peak is revered as a form of Shiva.[132][133][134] Pashupatinath is a sacred site in Shaivism.[135] Muktinath is considered sacred to both Hindus and Buddhists and is considered one of the Shakta pithas and part of Char Dham of Nepal. It houses saligrama stones, considered to be an incarnation of Vishnu by Hindus and Gawo Jagpa by Buddhists.[136]

For the Buddhists, Paro Taktsang is a religious site where Padmasambhava is said to have established Buddhism in Bhutan.[137][138] A number of Vajrayana Buddhist sites and monasteries are situated in the Himalayas.[139][140] In Jainism, Mount Ashtapada of the Himalayan mountain range is a sacred place where Rishabhanatha, the first Jain tirthankara, attained liberation. It is believed that after Rishabhanatha attained nirvana, his son Bharata constructed three stupas and 24 shrines of the Tirthankaras with their idols in the Himalayas.[141][142]

The Himalayan people's diversity shows through their architecture, their languages, and dialects, their beliefs and rituals, and clothing. The shapes and materials of the people's homes reflect their practical needs and beliefs. The handwoven textiles of the region display colors and patterns unique to their ethnic backgrounds. Some Himalayan ethnicities give great importance to jewelry such as the Rai and Limbu, where women wear big gold earrings and nose rings to show their wealth through their jewelry.[143]

Economy

The Himalayas contributes to the economy of the hilly region and the plains below. As the range stretches across various ecological zones, the economy of various regions of the Himalayas depends on the availability of resources. The Himalayan mountain range and its associated forests have extensive natural resources.[144] The fertile alluvium deposited by the Himalayan rivers have contributed to some the most fertile and arable lands. [145] Fruits such as apple, pear, peach, cherry, and grape are grown in fertile river valleys and lake beds. The climate also supports extensive cultivation of nuts such as walnut, and almond. Tea and spices are grown on the hills of Eastern Himalayas, which has the conducive climate and soil. The forests provide various natural resources, which form the livelihood of various ethnic tribes in the region.[144][115]

Due to the higher rate of flow of the Himalayan rivers, they have been dammed at multiple places for development of irrigation facilities and generation of hydroelectricity. Many of the nomadic and pastoral tribes rear livestock along the ranges of the Himalayas. They migrate to higher altitudes for grazing during the post spring season, when new pastures form and return to lower altitudes during the winters. The region is also rich in minerals, thought access has been an issue. In the Western Himalays, coal is found in Jammu region, bauxite, copper, and iron ore in Kashmir valley, borax and sulfur in Ladakh, and semi precious stones such as sapphire in Zanskar range. The Eastern Himalayas consist of deposits of gypsum, mica, graphite, coal, and various metal ores.[144]

There are a number of hill stations and religious centers on the lower ranges of the Himalayas and hence tourism is an important economic activity in the region.[146][147] Due to the presence of major peaks, mountaineering has become a major source of income and employment in the Central Himalayan region. However, the increased inflow of tourists and the associated infrastructure projects have resulted in pressure on the fragile ecosystem and depletion of the natural resources.[148][149][150] Sustainable tourism has been mooted as an alternative in the recent years.[151][152] The increasing growth of population has resulted in reduction in forest cover for agriculture, and other requirements such as firewood and timber.[144]

Transportation

Mountain trails with crossovers at mountain passes were the earlier means of travel and communication within the Himalayas. Since the late 20th century, road construction began in the region, which enabled transportation with the mountain valleys from both the sides of the Himalayas.[144] The Karakoram Highway connects the Pakistan administered Kashmir with Xinjiang region in China in the northwestern part of the Himalayas.[153] The Hindustan-Tibet Road (NH 5) stretches from the Indo-Pakistan border in the west to the India-China border in the east, before crossing over to Tibet at Shipka Pass. Other major roads in the western Himalayas include the Manali-Leh Highway connecting Himachal Pradesh with Ladakh, Srinagar-Leh highway (NH1) connecting the Vale of Kashmir with Ladakh through Khardung pass, and the Jammu–Srinagar Highway (NH 44) connecting Kashmir with rest of India through the Pir Panjal Range.[144][154][155]

In the eastern part in Nepal, the East-West Highway runs along the entire country in the east-west direction along the lower Himalayas. The Kathmandu–Terai Expressway connects the Kathmandu valley with Pokhara, the Arniko Highway connects Kathmandu with China through the Kodari pass and the Tribhuvan Highway links Kathmandu with the NH 28 on the Indian side.[144][154][156] The Indian state of Sikkim is connected to Tiber via through mountain passes at Jelep La and Nathu La.[157] Several motorable highways connect the North East Indian states with the rest of India.[144][154]

The majority of the railway lines in the region are on the Indian side, operated by Indian Railways.[158] There are two narrow gauge railway mountain railway lines–Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in West Bengal opened in 1881, and Kalka-Shimla Railway in Himachal Pradesh operating since 1903.[159] There is a narrow gauge railway line between Raxaul in Indian state of Bihar and Amlekhganj in Nepal.[160] Other railway lines include Jammu–Baramulla line in the Indian Kashmir region and Kangra Valley Railway in the Kumaon region.[144]

Multiple airstrips have been constructed on both the sides of the Himalayas for both civilian and military purposes. The major international airports in the Himalayas are the Kathmandu airport in the Kathmandu valley and Srinagar airport in the Vale of Kashmir. There are several other airports and airstrips, which support regional and limited international flights.[144] These include some of the world's highest and dangerous airports such as Tenzing-Hillary Airport in Nepal, and Paro Airport in Bhutan.[161][162] Daulat Beg Oldi in Ladakh is the oldest airstrip in the world.[163]

See also

Notes

- ^ Sovereignty over the range is contested in several places, most notably in the Kashmir region.[1][2]

- ^ Sanskrit: [ɦɪmaːlɐjɐ]; from Sanskrit himá 'snow, frost' and ā-laya 'dwelling, abode'),[3]

References

- ^ a b c d Bishop, Barry; Chatterjee, Shiba. "Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 8–12.

- ^ "Himalayan". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

Etymology: < Himālaya (Sanskrit < hima snow + ālaya dwelling, abode) + -an suffix)

(Subscription or participating institution membership required.) - ^ "BEN Cologne Scan". Sanskrit-lexicon. p. 1115. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ H.H. Wilson (1832). "WIL Cologne Scan". Sanskrit-lexicon. p. 976. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Himālay". Sanskrit-lexicon. p. 1299. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Him". Sanskrit-lexicon. p. 1298. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ H.H. Wilson (1832). "Alaya, a dictionary in Sanskrit and English". Sanskrit-lexicon. p. 121. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-8-184-75277-9.

- ^ "Nepali-English Dictionary" (PDF). Nepal Research. p. 56. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Translation of ཧི་མ་ལ་ཡ into English". Glosbe. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Himaliya death zone". BBC News (in Urdu). 26 June 2024. Archived from the original on 26 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "হিমালয় in English". English-Bangla. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Ximalaya". Reverso. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Dickinson, Emily, The Himmaleh was known to stoop.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David (1849), A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

- ^ Wadia, D. N. (1931). "The syntaxis of the northwest Himalaya: its rocks, tectonics and orogeny". Geological Survey of India. 65 (2): 189–220.

- ^ A.B.Roy; Ritesh Purohit (2018). "The Himalayas: Evolution Through Collision". Indian Shield: Precambrian Evolution and Phanerozoic Reconstitution. Elsevier. pp. 311–327. ISBN 978-0-128-09839-4.

- ^ "The Eight-Thousanders Of The Himalayas And The Karakoram". World Atlas. 16 August 2018. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ S. Sathyakumar; Mansi Mungee; Ranjana Pal (2020). "Biogeography of the Mountain Ranges of South Asia". Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes. Elsevier. pp. 543–554. ISBN 978-0-124-09548-9.

- ^ a b "Physiography of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 September 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Nag & Sengupta 1992, p. 40.

- ^ "Siwalik". Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Lesser Himalayas". Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Great Himalayas". Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Dubey, A.K. (2014). "The Tethys Himalaya". Understanding an Orogenic Belt. Springer Geology. pp. 345–352. ISBN 978-3-319-05588-6.

- ^ a b Nag & Sengupta 1992, p. 42.

- ^ "Western Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ a b c "Geographical Divisions of India" (PDF). NCERT. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Western Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Eastern Himalayas (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature (Report). February 2005. p. 2. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Nepal Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Assam Himalayas". Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Physical features". Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Geologists Find: An Earth Plate Is Breaking in Two". Columbia University. 7 July 1995. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Davies 2022, p. 81.

- ^ "The Himalayas: Two continents collide". USGS. 5 May 1999. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Frisch, Meschede & Blakey 2011, p. 209.

- ^ Sakai, Harutaka; Sawada, Minoru; Takigami, Yutaka; Orihashi, Yuji; Danhara, Tohru; Iwano, Hideki; Kuwahara, Yoshihiro; Dong, Qi; Cai, Huawei; Li, Jianguo (December 2005). "Geology of the summit limestone of Mount Qomolangma (Everest) and cooling history of the Yellow Band under the Qomolangma detachment". The Island Arc. 14 (4): 297–310. Bibcode:2005IsArc..14..297S. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.2005.00499.x. ISSN 1038-4871. S2CID 140603614. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Frisch, Meschede & Blakey 2011, p. 211.

- ^ Chakrabarti 2016, pp. 5–9.

- ^ Garzanti, Eduardo; Limonta, Mara; Resentini, Alberto; Bandopadhyay, Pinaki C.; Najman, Yani; Andò, Sergio; Vezzoli, Giovanni (1 August 2013). "Sediment recycling at convergent plate margins (Indo-Burman Ranges and Andaman–Nicobar Ridge)". Earth-Science Reviews. 123: 113–132. Bibcode:2013ESRv..123..113G. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.04.008. ISSN 0012-8252.

- ^ "Plate Tectonics -The Himalayas". The Geological Society. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Frisch, Meschede & Blakey 2011, p. 11.

- ^ "Devastating earthquakes are priming the Himalaya for a mega-disaster". National Geographic. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "The Himalayas – Himalayas Facts". PBS. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b Kulkarni, Anil V.; Karyakarte, Yogesh (2014). "Observed changes in Himalayan Glaciers". Current Science. 106 (2): 237–244. JSTOR 24099804. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "The Himalayan Glaciers, Fourth assessment report on climate change". IPCC. 2007. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Potocki, Mariusz; Mayewski, Paul Andrew; Matthews, Tom; Perry, L. Baker; Schwikowski, Margit; Tait, Alexander M.; Korotkikh, Elena; Clifford, Heather; Kang, Shichang; Sherpa, Tenzing Chogyal; Singh, Praveen Kumar; Koch, Inka; Birkel, Sean (2022). "Mt. Everest's highest glacier is a sentinel for accelerating ice loss". Nature. 5 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1038/s41612-022-00230-0. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Himalayas, Drainage". Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Glacier maps". Elsevier. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (2011). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and Last Glacial Maximum) Ice Cover of High and Central Asia, with a Critical Review of Some Recent OSL and TCN Dates". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L.; Hughes, P.D. (eds.). Quaternary Glaciation – Extent and Chronology, A Closer Look. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV. pp. 943–965.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (1987). "Subtropical mountain- and highland-glaciation as ice age triggers and the waning of the glacial periods in the Pleistocene". GeoJournal. 14 (4): 393–421. Bibcode:1987GeoJo..14..393M. doi:10.1007/BF02602717. S2CID 129366521.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (2005). "The maximum Ice Age (Würmian, Last Ice Age, LGM) glaciation of the Himalaya – a glaciogeomorphological investigation of glacier trim-lines, ice thicknesses and lowest former ice margin positions in the Mt. Everest-Makalu-Cho Oyu massifs (Khumbu- and Khumbakarna Himal) including information on late-glacial-, neoglacial-, and historical glacier stages, their snow-line depressions and ages". GeoJournal. 62 (3–4): 193–650. doi:10.1007/s10708-005-2338-6.

- ^ a b Lee, Ethan; Carrivick, Jonathan L.; Quincey, Duncan J.; Cook, Simon J.; James, William H. M.; Brown, Lee E. (20 December 2021). "Accelerated mass loss of Himalayan glaciers since the Little Ice Age". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 24284. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1124284L. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-03805-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8688493. PMID 34931039.

- ^ a b "Vanishing Himalayan Glaciers Threaten a Billion". Reuters. 4 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Kaushik, Saurabh; Rafiq, Mohammd; Joshi, P.K.; Singh, Tejpal (April 2020). "Examining the glacial lake dynamics in a warming climate and GLOF modelling in parts of Chandra basin, Himachal Pradesh, India". Science of the Total Environment. 714: 136455. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.71436455K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136455. PMID 31986382. S2CID 210933887.

- ^ Rafiq, Mohammd; Romshoo, Shakil Ahmad; Mishra, Anoop Kumar; Jalal, Faizan (January 2019). "Modelling Chorabari Lake outburst flood, Kedarnath, India". Journal of Mountain Science. 16 (1): 64–76. Bibcode:2019JMouS..16...64R. doi:10.1007/s11629-018-4972-8. ISSN 1672-6316. S2CID 134015944.

- ^ "Glaciers melting at alarming speed". People's Daily Online. 24 July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ Himalayan Glaciers: Climate Change, Water Resources, and Water Security. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2012. doi:10.17226/13449. ISBN 978-0-309-26098-5.

- ^ Shrestha, AB; Agrawal, NK; Alfthan, B; Bajracharya, SR; Maréchal, J; van Oort, B, eds. (2015). The Himalayan Climate and Water Atlas: Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Five of Asia's Major River Basins. ICIMOD, GRID-Arendal and CICERO. p. 58. ISBN 978-9-291-15357-2. Archived from the original on 17 August 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Indus River". Britannica. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Ganges River". Britannica. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Brahmaputra River". Britannica. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Sunderbans the world's largest delta". Gits4u. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Gaillardet, J.; Métivier, F.; Lemarchand, D.; Dupré, B.; Allègre, C.J.; Li, W.; Zhao, J. (2003). "Geochemistry of the Suspended Sediments of Circum-Himalayan Rivers and Weathering Budgets over the Last 50 Myrs" (PDF). Geophysical Research Abstracts. 5: 13,617. Bibcode:2003EAEJA....13617G. Abstract 13617. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- ^ a b c d e High Altitude Himalayan Lakes (PDF) (Report). Indian Space Research Organisation. January 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Drews, Carl. "Highest Lake in the World". Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "Pangong". Government of Ladakh. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Wular Lake". Global nature. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Waterbodies of Jammu and Kashmir (PDF) (Report). Government of Jammu and Kashmir. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b O'Neill, A. R. (2019). "Evaluating high-altitude Ramsar wetlands in the Sikkim Eastern Himalayas". Global Ecology and Conservation. 20 (e00715): 19. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00715.

- ^ "Tsho Rolpa". Rolwaling. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c O'Neill, Alexander; et al. (25 February 2020). "Establishing Ecological Baselines Around a Temperate Himalayan Peatland". Wetlands Ecology & Management. 28 (2): 375–388. Bibcode:2020WetEM..28..375O. doi:10.1007/s11273-020-09710-7. S2CID 211081106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Climate of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 50.

- ^ "Weather & Season Info of Nepal". Classic Himalaya. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 52.

- ^ a b Barry 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Barry 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Shi, Yafeng; Xie, Zizhu; Zheng, Benxing; Li, Qichun (1978). "Distribution, Feature and Variations of Glaciers in China" (PDF). World Glacier Inventory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2013.

- ^ Henderson-Sellers, Ann; McGuffie, Kendal (2012). The Future of the World's Climate: A Modelling Perspective. Elsevier. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-0-12-386917-3.

- ^ Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Barry 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Romshoo, Shakil Ahmad; Rafiq, Mohammd; Rashid, Irfan (March 2018). "Spatio-temporal variation of land surface temperature and temperature lapse rate over mountainous Kashmir Himalaya". Journal of Mountain Science. 15 (3): 563–576. Bibcode:2018JMouS..15..563R. doi:10.1007/s11629-017-4566-x. ISSN 1672-6316. S2CID 134568990.

- ^ Kad, Pratik; Ha, Kyung-Ja (27 November 2023). "Recent Tangible Natural Variability of Monsoonal Orographic Rainfall in the Eastern Himalayas". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 128 (22). AGU. Bibcode:2023JGRD..12838759K. doi:10.1029/2023JD038759.

- ^ Devitt, Terry (3 May 2001). "Climate shift linked to rise of Himalayas, Tibetan Plateau". University of Wisconsin–Madison News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Clift & Plumb 2008, p. 14–21.

- ^ Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 54.

- ^ a b c "Climate Change". World Wide Fund for Nature. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Wester, Philippus; Mishra, Arabinda; Mukherji, Aditi; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta, eds. (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. LCCN 2018954855.

- ^ Gentle, Popular; Thwaites, Rik; Race, Digby; Alexander, Kim (November 2014). "Differential impacts of climate change on communities in the middle hills region of Nepal". Natural Hazards. 74 (2): 815–836. Bibcode:2014NatHa..74..815G. doi:10.1007/s11069-014-1218-0. hdl:1885/66271. S2CID 129787080.

- ^ "Climate Change Policy, 2011" (PDF). Government of Nepal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Krishnan, Raghavan; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta; Ren, Guoyu; Rajbhandari, Rupak; Saeed, Sajjad; Sanjay, Jayanarayanan; Syed, Md. Abu.; Vellore, Ramesh; Xu, Ying; You, Qinglong; Ren, Yuyu (2019). "Unravelling Climate Change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Rapid Warming in the Mountains and Increasing Extremes". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. Springer Nature. pp. 57–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_3. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. S2CID 134572569. Archived from the original on 28 September 2024. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Damian Carrington (4 February 2019). "A third of Himalayan ice cap doomed, finds report". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Bolch, Tobias; Shea, Joseph M.; Liu, Shiyin; Azam, Farooq M.; Gao, Yang; Gruber, Stephan; Immerzeel, Walter W.; Kulkarni, Anil; Li, Huilin; Tahir, Adnan A.; Zhang, Guoqing; Zhang, Yinsheng (5 January 2019). "Status and Change of the Cryosphere in the Extended Hindu Kush Himalaya Region". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. Springer Nature. pp. 209–255. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_7. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. S2CID 134814572. Archived from the original on 28 September 2024. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Scott, Christopher A.; Zhang, Fan; Mukherji, Aditi; Immerzeel, Walter; Mustafa, Daanish; Bharati, Luna (5 January 2019). "Water in the Hindu Kush Himalaya". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. Springer Nature. pp. 257–299. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_8. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. S2CID 133800578.

- ^ "Countries most affected by climate change". World Food Program. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Almulhim, Abdulaziz I.; Alverio, Gabriela Nagle; Sharifi, Ayyoob; Shaw, Rajib; Huq, Saleemul; Mahmud, Md Juel; Ahmad, Shakil; Abubakar, Ismaila Rimi (14 June 2024). "Climate-induced migration in the Global South: an in depth analysis". Nature Partner Journals. 3: 47. Bibcode:2024npjCA...3...47A. doi:10.1038/s44168-024-00133-1. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Agrawal, A; Perrin, N (2008). Climate adaptation, local institutions and rural livelihoods. University of Michigan. pp. 350–367.

- ^ Devkota, Fidel (1 August 2013). "Climate Change and its socio-cultural impact in the Himalayan region of Nepal – A Visual Documentation". Anthrovision. Vaneasa Online Journal. 1 (2). doi:10.4000/anthrovision.589. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Rublee, Caitlin; Bhatta, Bishnu; Tiwari, Suresh; Pant, Suman (29 November 2023). "Three Climate and Health Lessons from Nepal Ahead of COP28". NAM Perspectives. 11 (29). doi:10.31478/202311f. PMC 11114597. PMID 38784635. S2CID 265597908.

- ^ Berstrand, s. "Fact Sheet | Climate, Environmental, and Health Impacts of Fossil Fuels (2021) | White Papers | EESI". EESI. Archived from the original on 31 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Oli, Madan K.; Taylor, Iain R.; Rogers, M. Elizabeth (1 January 1994). "Snow leopard Panthera uncia predation of livestock: An assessment of local perceptions in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal". Biological Conservation. 68 (1): 63–68. Bibcode:1994BCons..68...63O. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)90547-9.

- ^ "Paris climate deal: US and China formally join pact". BBC News. 3 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "India Ratifies Landmark Paris Climate Deal, Says, 'Kept Our Promise'". NDTV. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Nepal". Climate Action Tracker. Archived from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Das, Suraj; Mishra, Anindya Jayanta (1 March 2023). "Climate change and the Western Himalayan community: Exploring the local perspective through food choices". Ambio. 52 (3): 534–545. Bibcode:2023Ambio..52..534D. doi:10.1007/s13280-022-01810-3. PMC 9735043. PMID 36480087.

- ^ a b Dhungana, Nabin; Silwal, Nisha; Upadhaya, Suraj; Khadka, Chiranjeewee; Regmi, Sunil Kumar; Joshi, Dipesh; Adhikari, Samjhana (1 June 2020). "Rural coping and adaptation strategies for climate change by Himalayan communities in Nepal". Journal of Mountain Science. 17 (6): 1462–1474. Bibcode:2020JMouS..17.1462D. doi:10.1007/s11629-019-5616-3. S2CID 219281555.

- ^ BMP. "Fire Lines and Lanes" (PDF). BMP No. 12, Fire Lines and Lanes.

- ^ "Indomalayan realm". Biology Online. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Wester, Philippus; Mishra, Arabinda; Mukherji, Aditi; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1. ISBN 978-3-319-92288-1. S2CID 199491088. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ a b c "Plant life of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Miehe, Georg; Miehe, Sabine; Vogel, Jonas; Co, Sonam; Duo, La (May 2007). "Highest Treeline in the Northern Hemisphere Found in Southern Tibet" (PDF). Mountain Research and Development. 27 (2): 169–173. doi:10.1659/mrd.0792. hdl:1956/2482. S2CID 6061587. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b Jahangeer A. Bhat; Munesh Kumar; Rainer W. Bussmann (2 January 2013). "Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya, India". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. PMC 3560114. PMID 23281594.

- ^ Gupta, Pankaj; Sharma, Vijay Kumar (2014). Healing Traditions of the Northwestern Himalayas. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-81-322-1925-5.

- ^ "Himalayan Forests Disappearing". Earth Island Journal. 21 (4): 7–8. 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Animal life of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). Monosson, E. (ed.). "Extremophile". Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, DC: National Council for Science and the Environment. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Sunita Chaudhary; Kabir Uddin; Nakul Chettri; Rajesh Thapa; Eklabya Sharma (17 August 2022). "Protected areas in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: A regional assessment of the status, distribution, and gaps". Society for Conservation Biology. 4 (10). Bibcode:2022ConSP...4E2793C. doi:10.1111/csp2.12793. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Nieves López Isquierdo. "Protected areas and biodiversity hotspot areas in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region". Grida. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ a b Apollo, M. (2017). "Chapter 9: The population of Himalayan regions – by the numbers: Past, present and future". In Efe, R.; Öztürk, M. (eds.). Contemporary Studies in Environment and Tourism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 143–159.

- ^ A.P. Dimri; B. Bookhagen; M. Stoffel; T. Yasunari (8 November 2019). Himalayan Weather and Climate and their Impact on the Environment. Springer Science. p. 380. ISBN 978-3-030-29684-1.

- ^ Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 70–71.

- ^ a b c "People of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 76–78.

- ^ Gupta, Pankaj; Sharma, Vijay Kumar (2014). Healing Traditions of the Northwestern Himalayas. Springer Science. ISBN 978-8-132-21925-5.

- ^ Dallapiccola, Anna (2002). Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. National Geographic. ISBN 978-0-500-51088-9.

- ^ "Himalaya". Wisdom library. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Char Dham Yatra". Government of Uttarakhand. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Jahangeer A. Bhat; Munesh Kumar; Rainer W. Bussmann (2 January 2013). "Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya, India". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. PMC 3560114. PMID 23281594.

- ^ "New shrine on Amarnath route". The Hindu. Chennai, India. PTI. 30 May 2005. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ "The pilgrimage to Amarnath". BBC News. 6 August 2002. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Shankar, Ravi (26 September 2021). "Motherlodes of Power: The story of India's 'Shakti Peethas'". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Dubey, Yashika (21 December 2023). "Pashupatinath Temple: The Celestial Abode of Lord Shiva in Nepal". Amar Granth. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Nepal's Top Pilgrimage and Holy Sites – The Abode of Spirituality". Nepali Sansar. 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.]

- ^ Pommaret, Francoise (2006). Bhutan Himalayan Mountains Kingdom (5th ed.). Odyssey Books. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-962-217-810-6.

- ^ Cantor, Kimberly (14 July 2016). "Paro, Bhutan: The Tiger's Nest". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Tibetan monks: A controlled life". BBC News. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ Mehra, P. L. (1960). "Lacunae in the Study of the History of Bhutan and Sikkim". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 23: 190–201. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44137539. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Jain, Arun Kumar (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Jainism. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-8-17835-723-2.

- ^ "To heaven and back". The Times of India. 11 January 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Economy of Himalayas". Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Indo Gangetic Plain" (PDF). University Grants Commission. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Howard, Christopher A (2016). Mobile Lifeworlds: An Ethnography of Tourism and Pilgrimage in the Himalayas. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315622026. ISBN 978-0-367-87798-9.

- ^ Lim, Francis Khek Ghee (2007). "Hotels as sites of power: tourism, status, and politics in Nepal Himalaya". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. New Series. 13 (3). Royal Anthropological Institute: 721–738. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00452.x.

- ^ Humbert-Droz, Blaise (2017). "Impacts of Tourism and Military Presence on Wetlands and Their Avifauna in the Himalayas". In Prins, Herbert H. T.; Namgail, Tsewang (eds.). Bird Migration across the Himalayas Wetland Functioning amidst Mountains and Glaciers. Foreword by H.H. The Dali Lama. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 343–358. ISBN 978-1-107-11471-5.

- ^ Nyaupane, Gyan P.; Chhetri, Netra (2009). "Vulnerability to Climate Change of Nature-Based Tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas". Tourism Geographies. 11 (1): 95–119. doi:10.1080/14616680802643359. S2CID 55042146.

- ^ Nyaupane, Gyan P.; Timothy, Dallen J., eds. (2022). Tourism and Development in the Himalya: Social, Environmental, and Economic Forces. Routledge Cultural Heritage and Tourism Series. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-46627-5.

- ^ Pati, Vishwambhar Prasad (2020). Sustainable Tourism Development in the Himalya: Constraints and Prospects. Environmental Science and Engineering. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58854-0. ISBN 978-3-030-58853-3. S2CID 229256111.

- ^ Serenari, Christopher; Leung, Yu-Fai; Attarian, Aram; Franck, Chris (2012). "Understanding environmentally significant behavior among whitewater rafting and trekking guides in the Garhwal Himalaya, India". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 20 (5): 757–772. Bibcode:2012JSusT..20..757S. doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.638383. S2CID 153859477.

- ^ Mahnaz Z. Ispahani (June 1989). Roads and Rivals: The Political Uses of Access in the Borderlands of Asia (First ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0801422201.

- ^ a b c Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 85–88.

- ^ "Rationalization of Numbering Systems of National Highways" (PDF). Government of India. 28 April 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Nepal road standard (PDF) (Report). Government of Nepal. June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Arora, Vibha (2008). "Routing the Commodities of the Empire through Sikkim (1817-1906)" (PDF). Commodities of Empire Working Paper. No. 9. Open University. p. 8. ISSN 1756-0098. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Railway map of India". Survey of India. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Mountain Railways of India". World Heritage List. World Heritage Committee. 1999. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ "Nepalese Railway and Economic Development: What Has Gone Wrong?". India Review. 11 June 2020. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Most Extreme Airports". History Specials. Season 1. Episode 104. The History Channel. 26 August 2010.

- ^ "The top 10 highest altitude airports in the world". Airport-technology. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 12 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Anant Bewoor (July 2020). Daulat Beg Oldi: Operating from the World's Highest Airfield (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 1 June 2024.

Bibliography

- Barry, Roger E (2008). Mountain Weather and Climate (3rd ed.). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86295-0.

- Chakrabarti, B. K. (2016). Geology of the Himalayan Belt: Deformation, Metamorphism, Stratigraphy. Amsterdam and Boston: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-128-02021-0.

- Clift, Peter D.; Plumb, R. Alan (2008). The Asian Monsoon: Causes, History and Effects. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84799-5.

- Davies, Geoffrey F. (2022). Stories from the Deep Earth: How Scientists Figured Out What Drives Tectonic Plates and Mountain Building. Cham: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-91359-5. ISBN 978-3-030-91358-8. S2CID 245636487.

- Nag, Prithvish; Sengupta, Smita (1992). Geography of India. Concept Publishing. ISBN 978-8-170-22384-9.