Herman the Archdeacon

Herman the Archdeacon (also Hermann the Archdeacon[2] and Hermann of Bury,[3] born before 1040, died late 1090s) was a member of the household of Herfast, Bishop of East Anglia, in the 1070s and 1080s. Thereafter, he was a monk of Bury St Edmunds Abbey in Suffolk for the rest of his life.

Herman was probably born in Germany. Around 1070 he entered Herfast's household, and according to a later source he became the bishop's archdeacon, which was at that time an important secretarial position. He assisted Herfast in his unsuccessful campaign to move his bishopric to Bury St Edmunds Abbey, against the opposition of its abbot, and helped to bring about a temporary reconciliation between the two men. He remained with the bishop until his death in 1084, but he later regretted supporting his campaign to move the bishopric and himself moved to the abbey by 1092.

Herman was a colourful character and a theatrical preacher, but he is chiefly known as an able scholar who wrote the Miracles of St Edmund, a hagiographical account of miracles believed to have been performed by Edmund, King of East Anglia after his death at the hands of a Danish Viking army in 869. Herman's account also covered the history of the eponymous abbey. After his death, two revised versions of his Miracles were written, a shortened anonymous work which cut out the historical information, and another by Goscelin, which was hostile to Herman.

Life

Herman is described by the historian Tom Licence as a "colourful figure".[4] His origin is unknown but it is most likely that he was German. Similarities between his works and those of Sigebert of Gembloux and an earlier writer, Alpert of Metz, both of whom were at the Abbey of St. Vincent in Metz, suggest that he was a monk there for a period between 1050 and 1070. He may have been a pupil in Sigebert's school before emigrating to East Anglia. Herman was probably born before 1040 as between around 1070 and 1084 he held an important secretarial post in the household of Herfast, Bishop of East Anglia, and Herman would have been too young for the post if he had been born later.[5] According to the fourteenth-century archivist and prior of Bury St Edmunds Abbey, Henry de Kirkestede, Herman was Herfast's archdeacon, a post which was administrative in the immediate post-Conquest period.[6]

Soon after his appointment as bishop in 1070, Herfast came into conflict with Baldwin, abbot of Bury St Edmunds Abbey, over his attempt, with Herman's secretarial assistance, to move his bishopric to the abbey.[7] Herfast's see was located at North Elmham when he was appointed and in 1072 he moved it to Thetford, but both minsters had an income which was grossly inadequate for a bishop's estate and Bury would have provided a much better base of operations.[8] Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent an angry letter to Herfast, demanding that he submit the dispute to Lanfranc's archiepiscopal court and concluding by requiring that Herfast "banish the monk Herman, whose life is notorious for its many faults, from your society and your household completely. It is my wish that he live according to a rule in an observant monastery, or – if he refuses to do this – that he depart from the kingdom of England." Lanfranc's informant was a clerk of Baldwin, who may have had a grudge against Herfast.[9] In spite of Lanfranc's demand for his expulsion, Herman remained with Herfast. In 1071, Baldwin went to Rome and secured a papal immunity for the abbey from episcopal control and from conversion into a bishop's see.[7] Baldwin was a physician to Edward the Confessor and William the Conqueror, and when Herfast almost lost his sight in a riding accident, Herman persuaded him to seek Baldwin's medical help and end their dispute, but Herfast later renewed his campaign, finally losing by a judgement of the king's court in 1081.[10]

Herman later regretted supporting Herfast in the dispute, and looking back on it he wrote:

- Nor will I omit to mention – now that the blush of shame is wiped away – that I frequently gave ear to the bishop in this matter; that, when he sent across the sea to the king already mentioned [William the Conqueror], seeking to establish his see at the abbey, I drafted the letters and wrote up those that were drafted. I also read the responses that he received.[11]

Herman stayed with Herfast until his death in 1084, but it is not clear whether he served the succeeding bishop, William de Beaufeu, and by 1092 he was a monk at Bury St Edmunds Abbey. He occupied senior roles there, probably precentor, and perhaps from about 1095 the position of prior or sub-prior.[12] The abbey's most important relics were the bloodstained undergarments of the saint it was named after, Edmund the Martyr, and Herman was an enthusiastic preacher who enjoyed displaying the relics to the common people. According to an account by a writer who was hostile to him, his disrespectful treatment of the undergarments on one occasion, in taking them out of their box and allowing people to kiss them for two pence, was punished by his death soon afterwards.[13] He probably died in June 1097 or 1098.[14]

Miracles of St Edmund

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the defeat of the Kingdom of East Anglia and killing of King Edmund (the Martyr) by a Viking army in 869, but almost nothing survives giving information about his life and reign apart from some coins in his name. Between about 890 and 910 the Danish rulers of East Anglia, who had recently converted to Christianity, issued a coinage commemorating Edmund as a saint, and in the early tenth century his remains were translated to what was to become Bury St Edmunds Abbey.[15] The first known hagiography of Edmund was Abbo of Fleury's Life of St Edmund in the late tenth century and the second was by Herman.[16][a] Edmund was a patron saint of the English people and kings, and a popular saint in the Middle Ages.[18]

Herman's historical significance in the view of historians lies in the Miracles of St Edmund (Latin: De Miraculis Sancti Edmundi), his hagiography of King Edmund.[19] His ultimate aim in this work, according to Licence, "was to validate belief in the power of God and St Edmund",[20] but it was also a work of history, using the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to provide a basic structure and covering not only Edmund's miracles but also the history of the abbey and good deeds of kings and bishops.[21] The Miracles was intended for an erudite audience with an advanced knowledge of Latin.[22] Like other writers of his time, he collected rare words, but his choice of vocabulary was unique. Licence comments that he employed "a convoluted style and recherché vocabulary, which included Grecisms, archaisms and neologisms ... Herman's penchant for odd vernacular proverbs, dark humour and comically paradoxical metaphors such as 'the anchor of disbelief', 'the knot of slackness', 'the burden of laziness', and 'trusting to injustice' is evident throughout his work."[23] His style was "mannerist", in the sense of "that tendency or approach in which the author says things 'not normally, but abnormally', to surprise, astonish, and dazzle the audience".[24] His writing was influenced by Christian and classical sources and he could translate a vernacular text into accurate and poetic Latin: Licence observes that "his inner Ciceronian was at peace with his inner Christian".[25] Summarising the Miracles, Licence says:

Herman's work was exceptional for its day in its historical vision and breadth. The product of a writer schooled at an abbey with an unusually strong interest in historical writing, it was no mere saint's Life or miracle collection ... Nor were its horizons limited like those of local institutional histories ... Although closer to their genre of composition, Herman's piece was developing into something bigger. The catalyst in this experiment was his desire to reinterpret St Edmund as the deputy of God interested in English affairs ... Herman's achievement was to create a seamless narrative of English history without annalistic entries, a feat that neither Byrhtferth of Ramsey at the turn of the eleventh century nor John of Worcester early in the twelfth undertook. Bede had accomplished it, and so would William of Malmesbury on a far more impressive scale in the 1120s.[26]

Herman may have written the first half, covering the period up to the Conquest, around 1070, but it is more likely that the whole work was written in the reign of King William II (1087–1100).[27] Herman's original text in his own hand does not survive, but a shorter version[b] forms part of a book which covers the official biography of the abbey's patron saint. As Herman clearly intended, the book is composed of Abbo's Life followed by the Miracles. It is a luxury product dating to around 1100.[29] This version has some blank spaces and the final miracle stops in the middle of a sentence, indicating that the copying ceased abruptly. A manuscript dating to 1377 includes seven miracles assigned by the scribe to Herman which are not in the Miracles, and they are probably the stories which were intended for the blank spaces.[30][c] Two copies survive of a version produced shortly after Herman's death which leaves out the historical sections and only includes the miracles.[32][d]

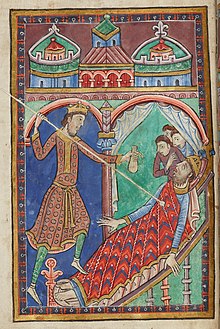

Another revised version of the Miracles (illustrated above) was written around 1100 and survives in a manuscript dating to the 1120s or 1130s.[34][e] It is attributed by Licence to the hagiographer and musician Goscelin, who is not recorded after 1106.[35] Herbert de Losinga, who was Bishop of East Anglia from 1091 to 1119, renewed Herfast's campaign to bring St Edmunds under episcopal control, against the opposition of Baldwin and his supporters, including Herman. The dispute continued after the deaths of Baldwin and Herman in the late 1090s, but like Herfast, Herbert was ultimately unsuccessful. Baldwin's death was followed by a battle over the appointment of a new abbot. Goscelin's text attacks Herbert's enemies, including Herman, and emphasises the role of bishops in Bury's history. The version was probably commissioned by Herbert.[36]

Herbert had bought the bishopric of East Anglia for himself, and the abbacy of New Minster, Winchester, for his father, from William II, and the father and son were attacked in an anonymous satire in fifty hexameters, On the Heresy Simony. Licence argues that Herman, who compared Herbert to Satan in the Miracles, was the author of the satire.[37]

The three versions of the Miracles, together with the additional seven miracles and On the Heresy Simony, are printed and translated by Licence.[38]

Controversy over authorship

The historian Antonia Gransden described the writer of the Miracles as "a conscientious historian, highly educated, and a gifted Latinist",[39] but she questioned Herman's authorship in a journal article in 1995 and her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article about Herman in 2004.[40] She stated that the earliest attribution of authorship to Herman is by Henry de Kirkestede in about 1370, and that there is no record of an archdeacon called Herman in the records of Norwich Cathedral, nor can the hagiographer be identified as a monk at St Edmunds Abbey. She thought that the author was probably a hagiographer praised by Goscelin called Bertrann, and de Kirkestede may have misread Bertrann for Hermann (her spelling).[39] Gransden's arguments are dismissed by Licence, who points out that the author of the Miracles confirmed his name by describing a monk called Herman of Binham as his namesake.[41]

Notes

- ^ Herman claimed to have found another early account of St Edmund's miracles, but he may have just have been following a standard practice of hagiographers of giving their works the authority of tradition by claiming to be following an ancient text.[17]

- ^ London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B. ii, fos. 20r–85v[28]

- ^ Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley, 240, fos. 623–677[31]

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Latin 2621, fos. 84r–92v and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Digby 39, fos. 24r–39v.[32] In Licence's view, both this version and the one in the official biography must derive from a lost intermediate text, because they have illiterate errors in common which would not have been made by Herman himself.[33]

- ^ New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 736, fos. 23r–76r[33]

References

- ^ Life and Miracles, Morgan Library, MS M.736 fol. 21v; Licence 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Gransden 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Williams 2004.

- ^ Licence 2009, p. 516.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xxxii, xxxv–xliv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xlvii–xlix.

- ^ a b Licence 2014, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Gransden 1995, p. 14; Licence 2014, pp. xv n. 9, xxxiii.

- ^ Licence 2009, p. 520; Licence 2014, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xxxi–xxxiv, xlvi–xlvii.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xlix–li.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. li–liv, 289, 295.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. cx.

- ^ Mostert 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. liv–lv; Winterbottom 1972.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lv.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xxxv; Farmer 2011, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxiii–lxiv; Hunt 1891, p. 249.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lx–lxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxi–lxii, lxix.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxviii.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxxxiii.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxxix–lxxxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxiii–lxiv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. liv–lix.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xci.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxi, xci.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. 337–349.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. 337.

- ^ a b Licence 2014, p. xcii.

- ^ a b Licence 2014, p. xciv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. cix, cxiv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. cxiv–cxxix.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. cii, cxi–cxiv; Harper-Bill 2004.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xcvi–cix, 115, 351–355; Harper-Bill 2004.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. 1–355.

- ^ a b Gransden 2004.

- ^ Gransden 1995; Gransden 2004.

- ^ Licence 2009, pp. 517–518; Licence 2014, p. 99.

Bibliography

- Farmer, David (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (5th revised ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959660-7.

- Gransden, Antonia (1995). "The Composition and Authorship of De Miraculis Sancti Edmundi: Attributed to Hermann the Archdeacon". The Journal of Medieval Latin. 5: 1–52. doi:10.1484/J.JML.2.304037. ISSN 0778-9750.

- Gransden, Antonia (2004). "Hermann (fl. 1070–1100)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13083. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Harper-Bill, Christopher (2004). "Losinga, Herbert de (d. 1119)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17025. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Hunt, William (1891). "Hermann (fl. 1070)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 26. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 249. OCLC 13955143.

- Licence, Tom (June 2009). "History and Hagiography in the Late Eleventh Century: The Life and Work of Herman the Archdeacon, Monk of Bury St Edmunds". English Historical Review. 124 (508): 516–544. doi:10.1093/ehr/cep145. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Licence, Tom, ed. (2014). Herman the Archdeacon and Goscelin of Saint-Bertin: Miracles of St Edmund (in Latin and English). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968919-4.

- "The Life and Miracles of St. Edmund". New York: The Morgan Library & Museum. 22 April 2016. MS M.736 fol. 21v. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Mostert, Marco (2014). "Edmund, St, King of East Anglia". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Eadred [Edred] (d. 955)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8510. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Winterbottom, Michael, ed. (1972). "Abbo: Life of St Edmund". Three Lives of English Saints (in Latin). Toronto, Canada: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies for the Centre for Medieval Studies. pp. 65–89. ISBN 978-0-88844-450-9.