H. H. Asquith

The Earl of Oxford and Asquith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Asquith c. 1910s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 April 1908 – 5 December 1916 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Campbell-Bannerman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 February 1920 – 21 November 1922 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Donald Maclean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Ramsay MacDonald | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 December 1916 – 14 December 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Carson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Donald Maclean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Liberal Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 30 April 1908 – 14 October 1926 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Campbell-Bannerman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Herbert Asquith 12 September 1852 Morley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 15 February 1928 (aged 75) Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Liberal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 10, including Raymond, Herbert, Arthur, Violet, Cyril, Elizabeth and Anthony | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | City of London School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Barrister | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last prime minister from the Liberal Party to command a majority government, and the most recent Liberal to have served as Leader of the Opposition. He played a major role in the design and passage of major liberal legislation and a reduction of the power of the House of Lords. In August 1914, Asquith took Great Britain and the British Empire into the First World War. During 1915, his government was vigorously attacked for a shortage of munitions and the failure of the Gallipoli Campaign. He formed a coalition government with other parties but failed to satisfy critics, was forced to resign in December 1916 and never regained power.

After attending Balliol College, Oxford, he became a successful barrister. In 1886, he was the Liberal candidate for East Fife, a seat he held for over thirty years. In 1892, he was appointed Home Secretary in Gladstone's fourth ministry, remaining in the post until the Liberals lost the 1895 election. In the decade of opposition that followed, Asquith became a major figure in the party, and when the Liberals regained power under Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman in 1905, Asquith was named Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1908, Asquith succeeded him as prime minister. The Liberals were determined to advance their reform agenda. An impediment to this was the House of Lords, which rejected the People's Budget of 1909. Meanwhile, the South Africa Act 1909 passed. Asquith called an election for January 1910, and the Liberals won, though they were reduced to a minority government. After another general election in December 1910, he gained passage of the Parliament Act 1911, allowing a bill three times passed by the Commons in consecutive sessions to be enacted regardless of the Lords. Asquith was less successful in dealing with Irish Home Rule. Repeated crises led to gun running and violence, verging on civil war.

When Britain declared war on Germany in response to the German invasion of Belgium, high-profile domestic conflicts were suspended regarding Ireland and women's suffrage. Asquith was more of a committee chair than a dynamic leader. He oversaw national mobilisation, the dispatch of the British Expeditionary Force to the Western Front, the creation of a mass army and the development of an industrial strategy designed to support the country's war aims. The war became bogged down and there was a call for better leadership. He was forced to form a coalition with the Conservatives and Labour early in 1915. He was weakened by his own indecision over strategy, conscription and financing.[1] David Lloyd George replaced him as prime minister in December 1916. They became bitter enemies and fought for control of the fast-declining Liberal Party. Asquith's role in creating the modern British welfare state (1906–1911) has been celebrated, but his weaknesses as a war leader and as a party leader after 1914 have been highlighted by historians. He remained the only prime minister between 1827 and 1979 to serve more than eight consecutive years in a single term.

Early life: 1852–1874

Family background

Asquith was born in Morley, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the younger son of Joseph Dixon Asquith (1825–1860) and his wife Emily, née Willans (1828–1888). The couple also had three daughters, of whom only one survived infancy.[2][3][a] The Asquiths were an old Yorkshire family, with a long nonconformist tradition.[b] It was a matter of family pride, shared by Asquith, that an ancestor, Joseph Asquith, was imprisoned for his part in the pro-Roundhead Farnley Wood Plot of 1664.[4]

Both Asquith's parents came from families associated with the Yorkshire wool trade. Dixon Asquith inherited the Gillroyd Mill Company, founded by his father. Emily's father, William Willans, ran a successful wool-trading business in Huddersfield. Both families were middle-class, Congregationalist, and politically radical. Dixon was a mild man, cultivated and in his son's words "not cut out" for a business career.[2] He was described as "a man of high character who held Bible classes for young men".[5] Emily suffered persistent poor health, but was of strong character, and a formative influence on her sons.[6]

Childhood and schooling

In his younger days, he was called Herbert ("Bertie" as a child) within the family, but his second wife called him Henry. His biographer Stephen Koss entitled the first chapter of his biography "From Herbert to Henry", referring to upward social mobility and his abandonment of his Yorkshire Nonconformist roots with his second marriage. However, in public, he was invariably referred to only as H. H. Asquith. "There have been few major national figures whose Christian names were less well known to the public" according to biographer Roy Jenkins.[2]

Herbert Asquith and his brother were educated at home by their parents until 1860, when Dixon Asquith died suddenly. William Willans took charge of the family, moved them to a house near his own, and arranged for the boys' schooling.[7] After a year at Huddersfield College they were sent as boarders to Fulneck School, a Moravian Church school near Leeds. In 1863 William Willans died, and the family came under the care of Emily's brother, John Willans. The boys went to live with him in London; when he moved back to Yorkshire in 1864 for business reasons, they remained in London and were lodged with various families.

The biographer Naomi Levine writes that in effect Asquith was "treated like an orphan" for the rest of his childhood.[8] The departure of his uncle effectively severed Asquith's ties with his native Yorkshire, and he described himself thereafter as "to all intents and purposes a Londoner".[9] Another biographer, H. C. G. Matthew, writes that Asquith's northern nonconformist background continued to influence him: "It gave him a point of sturdy anti-establishmentarian reference, important to a man whose life in other respects was a long absorption into metropolitanism."[10]

The boys were sent to the City of London School as day boys. Under the school's headmaster, E. A. Abbott, a distinguished classical scholar, Asquith became an outstanding pupil. He later said that he was under deeper obligations to his old headmaster than to any man living;[11] Abbott disclaimed credit for the boy's progress: "I never had a pupil who owed less to me and more to his own natural ability."[11][12] Asquith excelled in classics and English, was little interested in sports, read voraciously in the Guildhall Library, and became fascinated with oratory. He visited the public gallery of the House of Commons, studied the techniques of famous preachers, and honed his own skills in the school debating society.[13] Abbott remarked on the cogency and clarity of his pupil's speeches, qualities for which Asquith became celebrated throughout the rest of his life.[14][15] Asquith later recalled seeing, as a schoolboy, the corpses of five murderers left hanging outside Newgate.[16]

Oxford

In November 1869, Asquith won a classical scholarship at Balliol College, Oxford, going up the following October. The college's prestige, already high, continued to rise under the recently elected Master, Benjamin Jowett. He sought to raise the standards of the college to the extent that its undergraduates shared what Asquith later called a "tranquil consciousness of effortless superiority".[17] Although Asquith admired Jowett, he was more influenced by T. H. Green, White's Professor of Moral Philosophy. The abstract side of philosophy did not greatly attract Asquith, whose outlook was always practical, but Green's progressive liberal political views appealed to him.[10]

Asquith's university career was distinguished—"striking without being sensational" in the words of his biographer, Roy Jenkins. An easy grasp of his studies left him ample time to indulge his liking for debate. In the first month at university he spoke at the Oxford Union. His official biographers, J. A. Spender and Cyril Asquith, commented that in his first months at Oxford "he voiced the orthodox Liberal view, speaking in support, inter alia, of the disestablishment of the Church of England, and of non-intervention in the Franco-Prussian War".[18] He sometimes debated against his Balliol contemporary Alfred Milner, who although then a Liberal was already an advocate of British imperialism.[19] He was elected Treasurer of the Union in 1872 but was defeated at his first attempt at the Presidency.[20] During the General Election in January and February 1874 he spoke against Lord Randolph Churchill, who was not yet a prominent politician, at nearby Woodstock.[21] He eventually became President of the Union in Trinity Term 1874, his last term as an undergraduate.[22][23]

Asquith was proxime accessit (runner-up) for the Hertford Prize in 1872, again proxime accessit for the Ireland Prize in 1873, and again for the Ireland in 1874, on that occasion coming so close that the examiners awarded him a special prize of books. However, he won the Craven Scholarship and graduated with what his biographers describe as an "easy" double first in Mods and Greats.[24] After graduating he was elected to a prize fellowship of Balliol.[25]

Early professional career: 1874–1886

After Oxford

Perhaps because of his stark beginnings, Asquith was always attracted to the comforts and accoutrements that money can buy. He was personally extravagant, always enjoying the good life—good food, good companions, good conversation and attractive women.

After his graduation in 1874, Asquith spent several months coaching Viscount Lymington, the 18-year-old son and heir of the Earl of Portsmouth. He found the experience of aristocratic country-house life agreeable.[27][28] He liked less the austere side of the nonconformist Liberal tradition, with its strong temperance movement. He was proud of ridding himself of "the Puritanism in which I was bred".[29] His fondness for fine wines and spirits, which began at this period, eventually earned him the sobriquet "Squiffy".[30]

Returning to Oxford, Asquith spent the first year of his seven-year fellowship in residence there. But he had no wish to pursue a career as a don; the traditional route for politically ambitious but unmoneyed young men was through the law.[28] While still at Oxford Asquith had already entered Lincoln's Inn to train as a barrister, and in 1875 he served a pupillage under Charles Bowen.[31] He was called to the bar in June 1876.[32]

Marriage and children

There followed what Jenkins calls "seven extremely lean years".[31] Asquith set up a legal practice with two other junior barristers. With no personal contacts with solicitors, he received few briefs.[c] Those that came his way he argued capably, but he was too fastidious to learn the wilier tricks of the legal trade: "he was constitutionally incapable of making a discreet fog ... nor could he prevail on himself to dispense the conventional patter".[33] He did not allow his lack of money to stop him from marrying. His bride, Helen Kelsall Melland (1854–1891), was the daughter of Frederick Melland, a physician in Manchester. She and Asquith had met through friends of his mother's.[33] The two had been in love for several years, but it was not until 1877 that Asquith sought her father's consent to their marriage. Despite Asquith's limited income—practically nothing from the bar and a small stipend from his fellowship—Melland consented after making inquiries about the young man's potential. Helen had a private income of several hundred pounds a year, and the couple lived in modest comfort in Hampstead. They had five children:

- Raymond Asquith (6 November 1878 – 15 September 1916), who married Katharine Horner (daughter of Sir John Horner) on 25 July 1907. They had three children.

- Herbert Asquith (11 March 1881 – 5 August 1947), who married Lady Cynthia Charteris (daughter of Hugo Richard Charteris, 11th Earl of Wemyss and 7th Earl of March) on 28 July 1910. They had three children.

- Arthur Asquith (24 April 1883 – 25 August 1939), who married Betty Constance Manners (daughter of John Manners-Sutton, 3rd Baron Manners) on 30 April 1918. They had four daughters.

- Violet Asquith (15 April 1887 – 19 February 1969), who married Sir Maurice Bonham Carter on 30 November 1915. They had four children.

- Cyril Asquith, Baron Asquith of Bishopstone (5 February 1890 – 24 August 1954),[10] who married Anne Pollock (daughter of Sir Adrian Donald Wilde Pollock) on 12 February 1918. They had four children.

The Spectator and politics

Between 1876 and 1884, Asquith supplemented his income by writing regularly for The Spectator, which at that time had a broadly Liberal outlook. Matthew comments that the articles Asquith wrote for the magazine give a good overview of his political views as a young man. He was staunchly radical, but as unconvinced by extreme left-wing views as by Toryism. Among the topics that caused debate among Liberals were British imperialism, the union of Great Britain and Ireland, and female suffrage. Asquith was a strong, though not jingoistic, proponent of the Empire, and, after initial caution, came to support home rule for Ireland. He opposed votes for women for most of his political career.[d] There was also an element of party interest: Asquith believed that votes for women would disproportionately benefit the Conservatives. In a 2001 study of the extension of the franchise between 1832 and 1931, Bob Whitfield concluded that Asquith's surmise about the electoral impact was correct.[34] In addition to his work for The Spectator, he was retained as a leader writer by The Economist, taught at evening classes, and marked examination papers.[35]

Asquith's career as a barrister began to flourish in 1883 when R. S. Wright invited him to join his chambers at the Inner Temple. Wright was the Junior Counsel to the Treasury, a post often known as "the Attorney General's devil",[36] whose function included giving legal advice to ministers and government departments.[36] One of Asquith's first jobs in working for Wright was to prepare a memorandum for the prime minister, W. E. Gladstone, on the status of the parliamentary oath in the wake of the Bradlaugh case. Both Gladstone and the Attorney General, Sir Henry James, were impressed. This raised Asquith's profile, though not greatly enhancing his finances. Much more remunerative were his new contacts with solicitors who regularly instructed Wright and now also began to instruct Asquith.[37]

Member of Parliament: 1886–1908

Queen's Counsel

In June 1886, with the Liberal party split on the question of Irish Home Rule, Gladstone called a general election.[38] There was a last-minute vacancy at East Fife, where the sitting Liberal member, John Boyd Kinnear, had been deselected by his local Liberal Association for voting against Irish Home Rule. Richard Haldane, a close friend of Asquith's and also a struggling young barrister, had been Liberal MP for the nearby Haddingtonshire constituency since December 1885. He put Asquith's name forward as a replacement for Kinnear, and only ten days before polling Asquith was formally nominated in a vote of the local Liberals.[39] The Conservatives did not contest the seat, putting their support behind Kinnear, who stood against Asquith as a Liberal Unionist. Asquith was elected with 2,863 votes to Kinnear's 2,489.[40]

The Liberals lost the 1886 election, and Asquith joined the House of Commons as an opposition backbencher. He waited until March 1887 to make his maiden speech, which opposed the Conservative administration's proposal to give special priority to an Irish Crimes Bill.[41][42] From the start of his parliamentary career Asquith impressed other MPs with his air of authority as well as his lucidity of expression.[43] For the remainder of this Parliament, which lasted until 1892, Asquith spoke occasionally but effectively, mostly on Irish matters.[44][45]

Asquith's legal practice was flourishing, and took up much of his time. In the late 1880s Anthony Hope, who later gave up the bar to become a novelist, was his pupil. Asquith disliked arguing in front of a jury because of the repetitiveness and "platitudes" required, but excelled at arguing fine points of civil law before a judge or in front of courts of appeal.[46] These cases, in which his clients were generally large businesses, were unspectacular but financially rewarding.[47]

From time to time Asquith appeared in high-profile criminal cases. In 1887 and 1888, he defended the radical Liberal MP, Cunninghame Graham, who was charged with assaulting police officers when they attempted to break up a demonstration in Trafalgar Square.[48] Graham was later convicted of the lesser charge of unlawful assembly.[49] In what Jenkins calls "a less liberal cause", Asquith appeared for the prosecution in the trial of Henry Vizetelly for publishing "obscene libels"—the first English versions of Zola's novels Nana, Pot-Bouille and La Terre, which Asquith described in court as "the three most immoral books ever published".[50]

Asquith's law career received a great and unforeseen boost in 1889 when he was named junior counsel to Sir Charles Russell at the Parnell Commission of Enquiry. The commission had been set up in the aftermath of damaging statements in The Times, based on forged letters, that Irish MP Charles Stuart Parnell had expressed approval of Dublin's Phoenix Park killings. When the manager of The Times, J. C. Macdonald, was called to give evidence Russell, feeling tired, surprised Asquith by asking him to conduct the cross-examination.[51] Under Asquith's questioning, it became plain that in accepting the forgeries as genuine, without making any check, Macdonald had, in Jenkins's phrase, behaved "with a credulity which would have been childlike had it not been criminally negligent".[52] The Manchester Guardian reported that under Asquith's cross-examination, Macdonald "squirmed and wriggled through a dozen half-formed phrases in an attempt at explanation, and finished none".[53] The accusations against Parnell were shown to be false, The Times was obliged to make a full apology, and Asquith's reputation was assured.[54][55] Within a year he had gained advancement to the senior rank of the bar, Queen's Counsel.[56]

Asquith appeared in two important cases in the early 1890s. He played an effective low-key role in the sensational Tranby Croft libel trial (1891), helping to show that the plaintiff had not been libelled. He was on the losing side in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1892), a landmark English contract law case that established that a company was obliged to meet its advertised pledges.[57][58]

Widower and cabinet minister

In September 1891, Helen Asquith died of typhoid fever, following a few days' illness while the family were on holiday in Scotland.[59] Asquith bought a house in Surrey, and hired nannies and other domestic staff. He sold the Hampstead property and took a flat in Mount Street, Mayfair, where he lived during the working week.[60]

The general election of July 1892 returned Gladstone and the Liberals to office, with intermittent support from the Irish Nationalist MPs. Asquith, who was then only 39 and had never served as a junior minister, accepted the post of Home Secretary, a senior Cabinet position. The Conservatives and Liberal Unionists jointly outnumbered the Liberals in the Commons, which, together with a permanent Unionist majority in the House of Lords, restricted the government's capacity to put reforming measures in place. Asquith failed to secure a majority for a bill to disestablish the Church in Wales, and another to protect workers injured at work, but he built up a reputation as a capable and fair minister.[10]

In 1893, Asquith responded to a request from Magistrates in the Wakefield area for reinforcements to police a mining strike. Asquith sent 400 Metropolitan policeman. After two civilians were killed in Featherstone when soldiers opened fire on a crowd, Asquith was subject to protests at public meetings for a period. He responded to a taunt, "Why did you murder the miners at Featherstone in '92?" by saying, "It was not '92, it was '93."[61]

When Gladstone retired in March 1894, Queen Victoria chose the Foreign Secretary, Lord Rosebery, as the new prime minister. Asquith thought Rosebery preferable to the other possible candidate, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir William Harcourt, whom he deemed too anti-imperialist—one of the so-called "Little Englanders"—and too abrasive.[62] Asquith remained at the Home Office until the government fell in 1895.[10]

Asquith had known Margot Tennant slightly since before his wife's death, and grew increasingly attached to her in his years as a widower. On 10 May 1894, they were married at St George's, Hanover Square. Asquith became a son in law of Sir Charles Tennant, 1st Baronet. Margot was in many respects the opposite of Asquith's first wife, being outgoing, impulsive, extravagant and opinionated.[63] Despite the misgivings of many of Asquith's friends and colleagues the marriage proved to be a success. Margot got on, if sometimes stormily, with her step-children. She and Asquith had five children of their own, only two of whom survived infancy:[63] Anthony Asquith (9 November 1902 – 21 February 1968), and Elizabeth Asquith (26 February 1897 – 7 April 1945), who married Prince Antoine Bibesco on 30 April 1919.

Out of office

The general election of July 1895 was disastrous for the Liberals, and the Conservatives under Lord Salisbury won a majority of 152. With no government post, Asquith divided his time between politics and the bar.[e] Jenkins comments that in this period Asquith earned a substantial, though not stellar, income and was never worse off and often much higher-paid than when in office.[64] Matthew writes that his income as a QC in the following years was around £5,000 to £10,000 per annum (around £500,000–£1,000,000 at 2015 prices).[10][65] According to Haldane, on returning to government in 1905 Asquith had to give up a £10,000 brief to act for the Khedive of Egypt.[66] Margot later claimed (in the 1920s, when they were short of money) that he could have made £50,000 per annum had he remained at the bar.[67]

The Liberal Party, with a leadership—Harcourt in the Commons and Rosebery in the Lords—who detested each other, once again suffered factional divisions. Rosebery resigned in October 1896 and Harcourt followed him in December 1898.[68][69] Asquith came under strong pressure to accept the nomination to take over as Liberal leader, but the post of Leader of the Opposition, though full-time, was then unpaid, and he could not afford to give up his income as a barrister. He and others prevailed on the former Secretary of State for War, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman to accept the post.[70]

During the Boer War of 1899–1902 Liberal opinion divided along pro-imperialist and "Little England" lines, with Campbell-Bannerman striving to maintain party unity. Asquith was less inclined than his leader and many in the party to censure the Conservative government for its conduct, though he regarded the war as an unnecessary distraction.[10] Joseph Chamberlain, a former Liberal minister, now an ally of the Conservatives, campaigned for tariffs to shield British industry from cheaper foreign competition. Asquith's advocacy of traditional Liberal free trade policies helped to make Chamberlain's proposals the central question in British politics in the early years of the 20th century. In Matthew's view, "Asquith's forensic skills quickly exposed deficiencies and self-contradictions in Chamberlain's arguments."[10] The question divided the Conservatives, while the Liberals were united under the banner of "free fooders" against those in the government who countenanced a tax on imported essentials.[71]

Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1905–1908

Salisbury's Conservative successor as prime minister, Arthur Balfour, resigned in December 1905, but did not seek a dissolution of Parliament and a general election.[f] King Edward VII invited Campbell-Bannerman to form a minority government. Asquith and his close political allies Haldane and Sir Edward Grey tried to pressure him into taking a peerage to become a figurehead prime minister in the House of Lords, giving the pro-empire wing of the party greater dominance in the House of Commons. Campbell-Bannerman called their bluff and refused to move.[72][73] Asquith was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. He held the post for over two years, and introduced three budgets.[74][75]

A month after taking office, Campbell-Bannerman called a general election, in which the Liberals gained a landslide majority of 132.[76] However, Asquith's first budget, in 1906, was constrained by the annual income and expenditure plans he had inherited from his predecessor Austen Chamberlain. The only income for which Chamberlain had over-budgeted was the duty from sales of alcohol.[g][77] With a balanced budget, and a realistic assessment of future public expenditure, Asquith was able, in his second and third budgets, to lay the foundations for limited redistribution of wealth and welfare provisions for the poor. Blocked at first by Treasury officials from setting a variable rate of income tax with higher rates on those with high incomes, he set up a committee under Sir Charles Dilke which recommended not only variable income tax rates but also a supertax on incomes of more than £5,000 a year. Asquith also introduced a distinction between earned and unearned income, taxing the latter at a higher rate. He used the increased revenues to fund old-age pensions, the first time a British government had provided them. Reductions in selective taxes, such as that on sugar, were aimed at benefiting the poor.[78]

Asquith planned the 1908 budget, but by the time he presented it to the Commons he was no longer chancellor. Campbell-Bannerman's health had been failing for nearly a year. After a series of heart attacks, Campbell-Bannerman resigned on 3 April 1908, less than three weeks before his death.[79] Asquith was universally accepted as the natural successor.[80] King Edward, who was on holiday in Biarritz, sent for Asquith, who took the boat train to France and kissed hands as prime minister in the Hôtel du Palais, Biarritz, on 8 April.[81]

Peacetime prime minister: 1908–1914

Appointments and cabinet

On Asquith's return from Biarritz, his leadership of the Liberals was affirmed by a party meeting (the first time this had been done for a prime minister).[10] He initiated a cabinet reshuffle. Lloyd George was promoted to be Asquith's replacement as chancellor. Winston Churchill succeeded Lloyd George as President of the Board of Trade, entering the Cabinet despite his youth (aged 33) and the fact that he had crossed the floor to become a Liberal only four years previously.[82]

Asquith demoted or dismissed a number of Campbell-Bannerman's cabinet ministers. Lord Tweedmouth, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was relegated to the nominal post of Lord President of the Council. Lord Elgin was sacked from the Colonial Office and the Earl of Portsmouth (whom Asquith had tutored) was too, as undersecretary at the War Office. The abruptness of their dismissals caused hard feelings; Elgin wrote to Tweedmouth, "I venture to think that even a prime minister may have some regard for the usages common among gentlemen ... I feel that even a housemaid gets a better warning."[h][83]

Historian Cameron Hazlehurst wrote that "the new men, with the old, made a powerful team".[84] The cabinet choices balanced the competing factions in the party; the appointments of Lloyd George and Churchill satisfied the radicals, while the whiggish element favoured Reginald McKenna's appointment as First Lord.[10]

Prime minister at leisure

Possessed of "a faculty for working quickly",[85] Asquith had considerable time for leisure. Reading[86] the classics, poetry and a vast range of English literature consumed much of his time. So did correspondence; intensely disliking the telephone, Asquith was a prolific letter writer.[87] Travelling, often to country houses owned by members of Margot's family, was almost constant, Asquith being a devoted "weekender".[88] He spent part of each summer in Scotland, with golf, constituency matters, and time at Balmoral as duty minister.[10] He and Margot divided their time between Downing Street and The Wharf,[89] a country house at Sutton Courtenay in Berkshire which they bought in 1912;[90] their London mansion, 20 Cavendish Square,[91] was let during his premiership. He was addicted to Contract bridge.[92]

Above all else, Asquith thrived on company and conversation. A clubbable man, he enjoyed "the companionship of clever and attractive women" even more.[93] Throughout his life, Asquith had a circle of close female friends, which Margot termed his "harem".[94] In 1912, one of these, Venetia Stanley became much closer. Meeting first in 1909–1910, by 1912 she was Asquith's constant correspondent and companion. Between that point and 1915, he wrote her some 560 letters, at a rate of up to four a day.[95] Although it remains uncertain whether or not they were lovers,[96] she became of central importance to him.[97] Asquith's thorough enjoyment of "comfort and luxury"[93] during peacetime, and his unwillingness to adjust his behaviour during conflict,[98] ultimately contributed to the impression of a man out of touch. Lady Tree's teasing question, asked at the height of the conflict, "Tell me, Mr Asquith, do you take an interest in the war?",[99] conveyed a commonly held view.

Asquith enjoyed alcohol and his drinking was the subject of considerable gossip. His relaxed attitude to drink disappointed the temperance element in the Liberal coalition[100] and some authors have suggested it affected his decision-making, for example in his opposition to Lloyd George's wartime attacks on the liquor trade.[101] The Conservative leader Bonar Law quipped "Asquith drunk can make a better speech than any of us sober". [102] His reputation suffered, especially as wartime crises demanded the full attention of the prime minister.[103] David Owen writes that Asquith was ordered by his doctor to rein in his consumption after a near-collapse in April 1911, but it is unclear whether he actually did so. Owen, a medical doctor by training, states that "by modern diagnostic standards, Asquith became an alcoholic while Prime Minister." Witnesses often remarked on his weight gain and red, bloated face.[104]

Domestic policy

Reforming the House of Lords

Asquith hoped to act as a mediator between members of his cabinet as they pushed Liberal legislation through Parliament. Events, including conflict with the House of Lords, forced him to the front from the start of his premiership. Despite the Liberals' massive majority in the House of Commons, the Conservatives had overwhelming support in the unelected upper chamber.[105][i] Campbell-Bannerman had favoured reforming the Lords by providing that a bill thrice passed by the Commons at least six months apart could become law without the Lords' consent, while diminishing the power of the Commons by reducing the maximum term of a parliament from seven to five years.[106] Asquith, as chancellor, had served on a cabinet committee that had written a plan to resolve legislative stalemates by a joint sitting of the Commons as a body with 100 of the peers.[107] The Commons passed a number of pieces of legislation in 1908 which were defeated or heavily amended in the Lords, including a Licensing Bill, a Scottish Small Landholders' Bill, and a Scottish Land Values Bill.[105]

None of these bills was important enough to dissolve parliament and seek a new mandate at a general election.[10] Asquith and Lloyd George believed the peers would back down if presented with Liberal objectives contained within a finance bill—the Lords had not obstructed a money bill since the 17th century and, after initially blocking Gladstone's attempt (as chancellor) to repeal Paper Duties, had yielded in 1861 when it was submitted again in a finance bill. Accordingly, the Liberal leadership expected that after much objection from the Conservative peers, the Lords would yield to policy changes wrapped within a budget bill.[108]

1909: People's Budget

In a major speech in December 1908, Asquith announced that the upcoming budget would reflect the Liberals' policy agenda, and the People's Budget that was submitted to Parliament by Lloyd George the following year greatly expanded social welfare programmes. To pay for them, it significantly increased both direct and indirect taxes.[10] These included a 20 per cent tax on the unearned increase in value in land, payable at death of the owner or sale of the land. There would also be a tax of 1⁄2d in the pound[j] on undeveloped land. A graduated income tax was imposed, and there were increases in imposts on tobacco, beer and spirits.[109] A tax on petrol was introduced despite Treasury concerns that it could not work in practice. Although Asquith held fourteen cabinet meetings to assure unity amongst his ministers,[10] there was opposition from some Liberals; Rosebery described the budget as "inquisitorial, tyrannical, and Socialistic".[110]

The budget divided the country and provoked bitter debate through the summer of 1909.[111] The Northcliffe Press (The Times and the Daily Mail) urged rejection of the budget to give tariff reform (indirect taxes on imported goods which, it was felt, would encourage British industry and trade within the Empire) a chance; there were many public meetings, some of them organised by dukes, in protest at the budget.[112] Many Liberal politicians attacked the peers, including Lloyd George in his Newcastle upon Tyne speech, in which he said "a fully-equipped duke costs as much to keep up as two Dreadnoughts; and dukes are just as great a terror and they last longer".[113] King Edward privately urged Conservative leaders Balfour and Lord Lansdowne to pass the Budget (this was not unusual, as Queen Victoria had helped to broker agreement between the two Houses over the Irish Church Act 1869 and the Third Reform Act in 1884).[114]

From July it became increasingly clear that the Conservative peers would reject the budget, partly in the hope of forcing an election.[115] If they rejected it, Asquith determined, he would have to ask the King to dissolve Parliament, four years into a seven-year term,[10] as it would mean the legislature had refused supply.[k] The budget passed the Commons on 4 November 1909, but was voted down in the Lords on the 30th, the Lords passing a resolution by Lord Lansdowne stating that they were entitled to oppose the finance bill as it lacked an electoral mandate.[116] Asquith had Parliament prorogued three days later for an election beginning on 15 January 1910, with the Commons first passing a resolution deeming the Lords' vote to be an attack on the constitution.[117]

1910: election and constitutional deadlock

The January 1910 general election was dominated by talk of removing the Lords' veto.[10][118] A possible solution was to threaten to have King Edward pack the House of Lords with freshly minted Liberal peers, who would override the Lords's veto; Asquith's talk of safeguards was taken by many to mean that he had secured the King's agreement to this. They were mistaken; the King had informed Asquith that he would not consider a mass creation of peers until after a second general election.[10]

Lloyd George and Churchill were the leading forces in the Liberals' appeal to the voters; Asquith, clearly tired, took to the hustings for a total of two weeks during the campaign, and when the polls began, journeyed to Cannes with such speed that he neglected an engagement with the King, to the monarch's annoyance.[119] The result was a hung parliament. The Liberals lost heavily from their great majority of 1906, but still finished with two more seats than the Conservatives. With Irish Nationalist and Labour support, the government would have ample support on most issues, and Asquith stated that his majority compared favourably with those enjoyed by Palmerston and Lord John Russell.[120]

Immediate further pressure to remove the Lords' veto now came from the Irish MPs, who wanted to remove the Lords' ability to block the introduction of Irish Home Rule. They threatened to vote against the Budget unless they had their way.[121][l] With another general election likely before long, Asquith had to make clear the Liberal policy on constitutional change to the country without alienating the Irish and Labour. This initially proved difficult, and the King's speech opening Parliament was vague on what was to be done to neutralise the Lords' veto. Asquith dispirited his supporters by stating in Parliament that he had neither asked for nor received a commitment from the King to create peers.[10] The cabinet considered resigning and leaving it up to Balfour to try to form a Conservative government.[122]

The budget passed the Commons again, and this time was approved by the Lords in April without a division.[123] The cabinet finally decided to back a plan based on Campbell-Bannerman's, that a bill passed by the Commons in three consecutive annual sessions would become law notwithstanding the Lords' objections. Unless the King guaranteed that he would create enough Liberal peers to pass the bill, ministers would resign and allow Balfour to form a government, leaving the matter to be debated at the ensuing general election.[124] On 14 April 1910, the Commons passed resolutions that would become the basis of the eventual Parliament Act 1911: to remove the power of the Lords to veto money bills, to reduce blocking of other bills to a two-year power of delay, and also to reduce the term of a parliament from seven years to five.[125] In that debate Asquith also hinted—in part to ensure the support of the Irish MPs—that he would ask the King to break the deadlock "in that Parliament" (i.e. that he would ask for the mass creation of peers, contrary to the King's earlier stipulation that there be a second election).[126][m]

These plans were scuttled by the death of Edward VII on 6 May 1910. Asquith and his ministers were initially reluctant to press the new king, George V, in mourning for his father, for commitments on constitutional change, and the monarch's views were not yet known. With a strong feeling in the country that the parties should compromise, Asquith and other Liberals met with Conservative leaders in a number of conferences through much of the remainder of 1910. These talks failed in November over Conservative insistence that there be no limits on the Lords's ability to veto Irish Home Rule.[10] When the Parliament Bill was submitted to the Lords, they made amendments that were not acceptable to the government.[127]

1910–1911: second election and Parliament Act

On 11 November, Asquith asked King George to dissolve Parliament for another general election in December, and on the 14th met again with the King and demanded assurances the monarch would create an adequate number of Liberal peers to carry the Parliament Bill. The King was slow to agree, and Asquith and his cabinet informed him they would resign if he did not make the commitment. Balfour had told King Edward that he would form a Conservative government if the Liberals left office but the new King did not know this. The King reluctantly gave in to Asquith's demand, writing in his diary that, "I disliked having to do this very much, but agreed that this was the only alternative to the Cabinet resigning, which at this moment would be disastrous".[128]

Asquith dominated the short election campaign, focusing on the Lords' veto in calm speeches, compared by his biographer Stephen Koss to the "wild irresponsibility" of other major campaigners.[129] In a speech at Hull, he stated that the Liberals' purpose was to remove the obstruction, not establish an ideal upper house, "I have always got to deal—the country has got to deal—with things here and now. We need an instrument [of constitutional change] that can be set to work at once, which will get rid of deadlocks, and give us the fair and even chance in legislation to which we are entitled, and which is all that we demand."[130]

The election resulted in little change to the party strengths (the Liberal and Conservative parties were exactly equal in size; by 1914 the Conservative Party would actually be larger owing to by-election victories). Nevertheless, Asquith remained in Number Ten, with a large majority in the Commons on the issue of the House of Lords. The Parliament Bill again passed the House of Commons in April 1911, and was heavily amended in the Lords. Asquith advised King George that the monarch would be called upon to create the peers, and the King agreed, asking that his pledge be made public, and that the Lords be allowed to reconsider their opposition. Once it was, there was a raging internal debate within the Conservatives on whether to give in, or to continue to vote no even when outnumbered by hundreds of newly created peers. After lengthy debate, on 10 August 1911 the Lords voted narrowly not to insist on their amendments, with many Conservative peers abstaining and a few voting in favour of the government; the bill was passed into law.[131]

According to Jenkins, although Asquith had at times moved slowly during the crisis, "on the whole, Asquith's slow moulding of events had amounted to a masterly display of political nerve and patient determination. Compared with [the Conservatives], his leadership was outstanding."[132] Churchill wrote to Asquith after the second 1910 election, "your leadership was the main and conspicuous feature of the whole fight".[129] Matthew, in his article on Asquith, found that, "the episode was the zenith of Asquith's prime ministerial career. In the British Liberal tradition, he patched rather than reformulated the constitution."[10]

Social, religious and labour matters

Despite the distraction of the problem of the House of Lords, Asquith and his government moved ahead with a number of pieces of reforming legislation. According to Matthew, "no peacetime premier has been a more effective enabler. Labour exchanges, the introduction of unemployment and health insurance ... reflected the reforms the government was able to achieve despite the problem of the Lords. Asquith was not himself a 'new Liberal', but he saw the need for a change in assumptions about the individual's relationship to the state, and he was fully aware of the political risk to the Liberals of a Labour Party on its left flank."[10] Keen to keep the support of the Labour Party, the Asquith government passed bills urged by that party, including the Trade Union Act 1913 (reversing the Osborne judgment) and in 1911 granting MPs a salary, making it more feasible for working-class people to serve in the House of Commons.[133]

Asquith had as chancellor placed money aside for the provision of non-contributory old-age pensions; the bill authorising them passed in 1908, during his premiership, despite some objection in the Lords.[134] Jenkins noted that the scheme (which provided five shillings a week to single pensioners aged seventy and over, and slightly less than twice that to married couples) "to modern ears sounds cautious and meagre. But it was violently criticised at the time for showing a reckless generosity."[135]

Asquith's new government became embroiled in a controversy over the Eucharistic Congress of 1908, held in London. Following the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, the Catholic Church had seen a resurgence in Britain, and a large procession displaying the Blessed Sacrament was planned to allow the laity to participate. Although such an event was forbidden by the 1829 act, planners counted on the British reputation for religious tolerance,[136] and Francis Cardinal Bourne, the Archbishop of Westminster, had obtained permission from the Metropolitan Police. When the plans became widely known, King Edward objected, as did many other Protestants. Asquith received inconsistent advice from his Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, and successfully pressed the organisers to cancel the religious aspects of the procession, though it cost him the resignation of his only Catholic cabinet minister, Lord Ripon.[137]

Disestablishment of the Welsh Church was a Liberal priority, but despite support by most Welsh MPs, there was opposition in the Lords. Asquith was an authority on Welsh disestablishment from his time under Gladstone, but had little to do with the passage of the bill. It was twice rejected by the Lords, in 1912 and 1913, but having been forced through under the Parliament Act received royal assent in September 1914, with the provisions suspended until war's end.[10][138]

Votes for women

Asquith had opposed votes for women as early as 1882, and he remained well known as an adversary throughout his time as prime minister.[139] He took a detached view of the women's suffrage question, believing it should be judged on whether extending the franchise would improve the system of government, rather than as a question of rights. He did not understand—Jenkins ascribed it to a failure of imagination—why passions were raised on both sides over the issue. He told the House of Commons in 1913, while complaining of the "exaggerated language" on both sides, "I am sometimes tempted to think, as one listens to the arguments of supporters of women's suffrage, that there is nothing to be said for it, and I am sometimes tempted to think, as I listen to the arguments of the opponents of women's suffrage, that there is nothing to be said against it."[140]

In 1906 suffragettes Annie Kenney, Adelaide Knight, and Jane Sbarborough were arrested when they tried to obtain an audience with Asquith.[141][142] Offered either six weeks in prison or giving up campaigning for one year, the women all chose prison.[141] Asquith was a target for militant suffragettes as they abandoned hope of achieving the vote through peaceful means. He was several times the subject of their tactics: approached (to his annoyance) arriving at 10 Downing Street (by Olive Fargus and Catherine Corbett whom he called 'silly women',[143] confronted at evening parties, accosted on the golf course, and ambushed while driving to Stirling to dedicate a memorial to Campbell-Bannerman. On the last occasion, his top hat proved adequate protection against the dog whips wielded by the women. These incidents left him unmoved, as he did not believe them a true manifestation of public opinion.[144]

With a growing majority of the Cabinet, including Lloyd George and Churchill, in favour of women's suffrage, Asquith was pressed to allow consideration of a private member's bill to give women the vote. The majority of Liberal MPs were also in favour.[145] Jenkins deemed him one of the two main prewar obstacles to women gaining the vote, the other being the suffragists's own militancy. In 1912, Asquith reluctantly agreed to permit a free vote on an amendment to a pending reform bill, allowing women the vote on the same terms as men. This would have satisfied Liberal suffrage supporters, and many suffragists, but the Speaker in January 1913 ruled that the amendment changed the nature of the bill, which would have to be withdrawn. Asquith was loud in his complaints against the Speaker, but was privately relieved.[146]

Asquith belatedly came around to support women's suffrage in 1917,[147] by which time he was out of office. Women over the age of thirty were eventually given the vote by Lloyd George's government under the Representation of the People Act 1918. Asquith's reforms to the House of Lords eased the way for the passage of the bill.[148]

Irish Home Rule

As a minority party after 1910 elections, the Liberals depended on the Irish vote, controlled by John Redmond. To gain Irish support for the budget and the parliament bill, Asquith promised Redmond that Irish Home Rule would be the highest priority.[149] It proved much more complex and time-consuming than expected.[150] Support for self-government for Ireland had been a tenet of the Liberal Party since 1886, but Asquith had not been as enthusiastic, stating in 1903 (while in opposition) that the party should never take office if that government would be dependent for survival on the support of the Irish Nationalist Party.[151] After 1910, though, Irish Nationalist votes were essential to stay in power. Retaining Ireland in the Union was the declared intent of all parties, and the Nationalists, as part of the majority that kept Asquith in office, were entitled to seek enactment of their plans for Home Rule, and to expect Liberal and Labour support.[10] The Conservatives, with die-hard support from the Protestant Orangemen of Ulster, were strongly opposed to Home Rule. The desire to retain a veto for the Lords on such bills had been an unbridgeable gap between the parties in the constitutional talks prior to the second 1910 election.[152]

The cabinet committee (not including Asquith) that in 1911 planned the Third Home Rule Bill opposed any special status for Protestant Ulster within majority-Catholic Ireland. Asquith later (in 1913) wrote to Churchill, stating that the Prime Minister had always believed and stated that the price of Home Rule should be a special status for Ulster. In spite of this, the bill as introduced in April 1912 contained no such provision, and was meant to apply to all Ireland.[10] Neither partition nor a special status for Ulster was likely to satisfy either side.[150] The self-government offered by the bill was very limited, but Irish Nationalists, expecting Home Rule to come by gradual parliamentary steps, favoured it. The Conservatives and Irish Unionists opposed it. Unionists began preparing to get their way by force if necessary, prompting nationalist emulation. Though very much a minority, Irish Unionists were generally better financed and more organised.[153]

Since the Parliament Act the Unionists could no longer block Home Rule in the House of Lords, but only delay Royal Assent by two years. Asquith decided to postpone any concessions to the Unionists until the bill's third passage through the Commons, when he believed the Unionists would be desperate for a compromise.[154] Jenkins concluded that had Asquith tried for an earlier agreement, he would have had no luck, as many of his opponents wanted a fight and the opportunity to smash his government.[155] Sir Edward Carson, MP for Dublin University and leader of the Irish Unionists in Parliament, threatened a revolt if Home Rule was enacted.[156] The new Conservative leader, Bonar Law, campaigned in Parliament and in northern Ireland, warning Ulstermen against "Rome Rule", that is, domination by the island's Catholic majority.[157] Many who opposed Home Rule felt that the Liberals had violated the Constitution—by pushing through major constitutional change without a clear electoral mandate, with the House of Lords, formerly the "watchdog of the constitution", not reformed as had been promised in the preamble of the 1911 Act—and thus justified actions that in other circumstances might be treason.[158]

The passions generated by the Irish question contrasted with Asquith's cool detachment, and he wrote about the prospective partition of the county of Tyrone, which had a mixed population, deeming it "an impasse, with unspeakable consequences, upon a matter which to English eyes seems inconceivably small, & to Irish eyes immeasurably big".[159] In 1912 Asquith said: "Ireland is a nation, not two nations but one nation. There are few cases in history, ...of nationality at once so distinct, so persistent and so assimilative as the Irish."[160] As the Commons debated the Home Rule bill in late 1912 and early 1913, unionists in the north of Ireland mobilised, with talk of Carson declaring a Provisional Government and Ulster Volunteer Forces (UVF) built around the Orange Lodges, but in the cabinet, only Churchill viewed this with alarm.[161] These forces, insisting on their loyalty to the British Crown but increasingly well-armed with smuggled German weapons, prepared to do battle with the British Army, but Unionist leaders were confident that the army would not aid in forcing Home Rule on Ulster.[159] As the Home Rule bill awaited its third passage through the Commons, the so-called Curragh incident occurred in April 1914. With deployment of troops into Ulster imminent and threatening language by Churchill and the Secretary of State for War, John Seely, around sixty army officers, led by Brigadier-General Hubert Gough, announced that they would rather be dismissed from the service than obey.[10] With unrest spreading to army officers in England, the Cabinet acted to placate the officers with a statement written by Asquith reiterating the duty of officers to obey lawful orders but claiming that the incident had been a misunderstanding. Seely then added an unauthorised assurance, countersigned by Sir John French (the professional head of the army), that the government had no intention of using force against Ulster. Asquith repudiated the addition, and required Seely and French to resign, taking on the War Office himself,[162] retaining the additional responsibility until hostilities against Germany began.[163]

Within a month of the start of Asquith's tenure at the War Office, the UVF landed a large cargo of guns and ammunition at Larne, but the Cabinet did not deem it prudent to arrest their leaders. On 12 May, Asquith announced that he would secure Home Rule's third passage through the Commons (accomplished on 25 May), but that there would be an amending bill with it, making special provision for Ulster. But the Lords made changes to the amending bill unacceptable to Asquith, and with no way to invoke the Parliament Act on the amending bill, Asquith agreed to meet other leaders at an all-party conference on 21 July at Buckingham Palace, chaired by the King. When no solution could be found, Asquith and his cabinet planned further concessions to the Unionists, but this did not occur as the crisis on the Continent erupted into war.[10] In September 1914, after the outbreak of the conflict, Asquith announced that the Home Rule bill would go on the statute book (as the Government of Ireland Act 1914) but would not go into force until after the war (see Suspensory Act 1914); in the interim a bill granting special status to Ulster would be considered. This solution satisfied neither side.[164]

Foreign and defence policy

Asquith led a deeply divided Liberal Party as prime minister, not least on questions of foreign relations and defence spending.[10] Under Balfour, Britain and France had agreed upon the Entente Cordiale.[165] In 1906, at the time the Liberals took office, there was an ongoing crisis between France and Germany over Morocco, and the French asked for British help in the event of conflict. Grey, the Foreign Secretary, refused any formal arrangement, but gave it as his personal opinion that in the event of war Britain would aid France. France then asked for military conversations aimed at co-ordination in such an event. Grey agreed, and these went on in the following years, without cabinet knowledge—Asquith most likely did not know of them until 1911. When he learnt of them, Asquith was concerned that the French took for granted British aid in the event of war, but Grey persuaded him the talks must continue.[166]

More public was the naval arms race between Britain and Germany. The Moroccan crisis had been settled at the Algeciras Conference, and Campbell-Bannerman's cabinet approved reduced naval estimates. Tenser relationships with Germany, and that nation moving ahead with its own dreadnoughts, led Reginald McKenna, when Asquith appointed him First Lord of the Admiralty in 1908, to propose the laying down of eight more British ones in the following three years. This prompted conflict in the Cabinet between those who supported this programme, such as McKenna, and the "economists" who promoted economy in naval estimates, led by Lloyd George and Churchill.[167] There was much public sentiment for building as many ships as possible to maintain British naval superiority. Asquith mediated among his colleagues and secured a compromise whereby four ships would be laid down at once, and four more if there proved to be a need.[168] The armaments matter was put to the side during the domestic crises over the 1909 budget and then the Parliament Act, though the building of warships continued at an accelerated rate.[169]

The Agadir Crisis of 1911 was again between France and Germany over Moroccan interests, but Asquith's government signalled its friendliness towards France in Lloyd George's Mansion House speech on 21 July.[170] Late that year, the Lord President of the Council, Viscount Morley, brought the question of the communications with the French to the attention of the Cabinet. The Cabinet agreed (at Asquith's instigation) that no talks could be held that committed Britain to war, and required cabinet approval for co-ordinated military actions. Nevertheless, by 1912, the French had requested additional naval co-ordination and late in the year, the various understandings were committed to writing in an exchange of letters between Grey and French Ambassador Paul Cambon.[171] The relationship with France disquieted some Liberal backbenchers and Asquith felt obliged to assure them that nothing had been secretly agreed that would commit Britain to war. This quieted Asquith's foreign policy critics until another naval estimates dispute erupted early in 1914.[172]

July Crisis and outbreak of World War I

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 initiated a month of unsuccessful diplomatic attempts to avoid war.[173] These attempts ended with Grey's proposal for a four-power conference of Britain, Germany, France and Italy, following the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia on the evening of 23 July. Grey's initiative was rejected by Germany as "not practicable".[174] During this period, George Cassar considers that "the country was overwhelmingly opposed to intervention."[175] Much of Asquith's cabinet was similarly inclined, Lloyd George told a journalist on 27 July that "there could be no question of our taking part in any war in the first instance. He knew of no Minister who would be in favour of it."[174] and wrote in his War Memoirs that before the German ultimatum to Belgium on 3 August "The Cabinet was hopelessly divided—fully one third, if not one half, being opposed to our entry into the War. After the German ultimatum to Belgium the Cabinet was almost unanimous."[176] Asquith himself, while growing more aware of the impending catastrophe, was still uncertain of the necessity for Britain's involvement. On 24 July, he wrote to Venetia, "We are within measurable, or imaginable, distance of a real Armageddon. Happily there seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators."[177]

During the continuing escalation Asquith "used all his experience and authority to keep his options open"[178] and adamantly refused to commit his government by saying, "The worst thing we could do would be to announce to the world at the present moment that in no circumstances would we intervene."[179] But he recognised Grey's clear commitment to Anglo-French unity and, following Russian mobilisation on 30 July,[180] and the Kaiser's ultimatum to the Tsar on 1 August, he recognised the inevitability of war.[181] From this point, he committed himself to participation, despite continuing Cabinet opposition. As he said, "There is a strong party reinforced by Ll George[, ] Morley and Harcourt who are against any kind of intervention. Grey will never consent and I shall not separate myself from him."[182] Also, on 2 August, he received confirmation of Conservative support from Bonar Law.[183] In one of two extraordinary Cabinets held on that Sunday, Grey informed members of the 1912 Anglo-French naval talks and Asquith secured agreement to mobilise the fleet.[184]

On Monday 3 August, the Belgian Government rejected the German demand for free passage through its country and in the afternoon, "with gravity and unexpected eloquence",[183] Grey spoke in the Commons and called for British action "against the unmeasured aggrandisement of any power".[185] Basil Liddell Hart considered that this speech saw the "hardening (of) British opinion to the point of intervention".[186] The following day Asquith saw the King and an ultimatum to Germany demanding withdrawal from Belgian soil was issued with a deadline of midnight Berlin time, 11.00 p.m. (GMT). Margot Asquith described the moment of expiry, somewhat inaccurately, in these terms: "(I joined) Henry in the Cabinet room. Lord Crewe and Sir Edward Grey were already there and we sat smoking cigarettes in silence ... The clock on the mantelpiece hammered out the hour and when the last beat of midnight struck it was as silent as dawn. We were at War."[187]

First year of the war: August 1914 – May 1915

Asquith's wartime government

The declaration of war on 4 August 1914 saw Asquith as the head of an almost united Liberal Party. Having persuaded Sir John Simon and Lord Beauchamp to remain,[188] Asquith suffered only two resignations from his cabinet, those of John Morley and John Burns.[189] With other parties promising to co-operate, Asquith's government declared war on behalf of a united nation, Asquith bringing "the country into war without civil disturbance or political schism".[190]

The first months of the War saw a revival in Asquith's popularity. Bitterness from earlier struggles temporarily receded and the nation looked to Asquith, "steady, massive, self-reliant and unswerving",[191] to lead them to victory. But Asquith's peacetime strengths ill-equipped him for what was to become perhaps the first total war and, before its end, he would be out of office for ever and his party would never again form a majority government.[192]

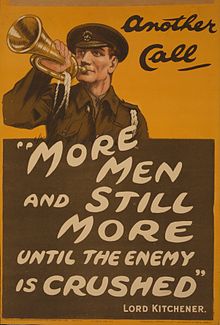

Beyond the replacement of Morley and Burns,[193] Asquith made one other significant change to his cabinet. He relinquished the War Office and appointed the non-partisan but Conservative-inclined Lord Kitchener of Khartoum.[194] Kitchener was a figure of national renown and his participation strengthened the reputation of the government.[195] Whether it increased its effectiveness is less certain.[99] Overall, it was a government of considerable talent with Lloyd George remaining as chancellor,[196] Grey as foreign secretary,[197] and Churchill at the Admiralty.[194]

The invasion of Belgium by German forces, the touch paper for British intervention, saw the Kaiser's armies attempt a lightning strike through Belgium against France, while holding Russian forces on the Eastern Front.[198] To support the French, Asquith's cabinet authorised the despatch of the British Expeditionary Force.[199] The ensuing Battle of the Frontiers in the late summer and early autumn of 1914 saw the final halt of the German advance at the First Battle of the Marne, which established the pattern of attritional trench warfare on the Western Front that continued until 1918.[200] This stalemate brought deepening resentment against the government, and against Asquith personally, as the population at large and the press lords in particular, blamed him for a lack of energy in the prosecution of the war.[201] It also created divisions within the Cabinet between the "Westerners", including Asquith, who supported the generals in believing that the key to victory lay in ever greater investment of men and munitions in France and Belgium,[202] and the "Easterners", led by Churchill and Lloyd George, who believed that the Western Front was in a state of irreversible stasis and sought victory through action in the East.[203] Lastly, it highlighted divisions between those politicians, and newspaper owners, who thought that military strategy and actions should be determined by the generals, and those who thought politicians should make those decisions.[204] Asquith said in his memoirs: "Once the governing objectives have been decided by Ministers at home—the execution should always be left to the untrammeled discretion of the commanders on the spot."[205] Lloyd George's counter view was expressed in a letter of early 1916 in which he asked "whether I have a right to express an independent view on the War or must (be) a pure advocate of opinions expressed by my military advisers?"[206] These divergent opinions lay behind the two great crises that would, within 14 months, see the collapse of the last ever fully Liberal administration and the advent of the first coalition on 25 May 1915, the Dardanelles Campaign and the Shell Crisis.[207]

Dardanelles Campaign

The Dardanelles Campaign was an attempt by Churchill and those favouring an Eastern strategy to end the stalemate on the Western Front. It envisaged an Anglo-French landing on Turkey's Gallipoli Peninsula and a rapid advance to Constantinople which would see the exit of Turkey from the conflict. The plan was rejected by Admiral Fisher, the First Sea Lord, and Kitchener.[208] Unable to provide decisive leadership, Asquith sought to arbitrate between these two and Churchill, leading to procrastination and delay. The naval attempt was badly defeated. Allied troops established bridgeheads on the Gallipoli Peninsula, but a delay in providing sufficient reinforcements allowed the Turks to regroup, leading to a stalemate Jenkins described "as immobile as that which prevailed on the Western Front".[209] The Allies suffered from infighting at the top, poor equipment, incompetent leadership, and lack of planning, while facing the best units of the Ottoman army. The Allies sent in 492,000 men; they suffered 132,000 casualties in the humiliating defeat—with very high rates for Australia and New Zealand that permanently transformed those dominions. In Britain, it was political ruin for Churchill and badly hurt Asquith.[210]

Shell Crisis of May 1915

The opening of 1915 saw growing division between Lloyd George and Kitchener over the supply of munitions for the army. Lloyd George considered that a munitions department, under his control, was essential to co-ordinate "the nation's entire engineering capacity".[211] Kitchener favoured the continuance of the current arrangement whereby munitions were sourced through contracts between the War Office and the country's armaments manufacturers. As so often, Asquith sought compromise through committee, establishing a group to "consider the much vexed question of putting the contracts for munitions on a proper footing".[212] This did little to dampen press criticism[213] and, on 20 April, Asquith sought to challenge his detractors in a major speech at Newcastle by saying, "I saw a statement the other day that the operations of our army were being crippled by our failure to provide the necessary ammunition. There is not a word of truth in that statement."[214]

The press response was savage: 14 May 1915 saw the publication in The Times of a letter from their correspondent Charles à Court Repington which ascribed the British failure at the Battle of Aubers Ridge to a shortage of high explosive shells. Thus opened a fully-fledged crisis, the Shell Crisis. The prime minister's wife correctly identified her husband's chief opponent, the Press baron, and owner of The Times, Lord Northcliffe: "I'm quite sure Northcliffe is at the bottom of all this,"[215] but failed to recognise the clandestine involvement of Sir John French, who leaked the details of the shells shortage to Repington.[216] Northcliffe claimed that "the whole question of the supply of the munitions of war is one on which the Cabinet cannot be arraigned too sharply."[217] Attacks on the government and on Asquith's personal lethargy came from the left as well as the right, C. P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian writing, "The Government has failed most frightfully and discreditably in the matter of munitions."[218]

Other events

Failures in both the East and the West began a tide of events that was to overwhelm Asquith's Liberal Government.[219] Strategic setbacks combined with a shattering personal blow when, on 12 May 1915, Venetia Stanley announced her engagement to Edwin Montagu. Asquith's reply was immediate and brief, "As you know well, this breaks my heart. I couldn't bear to come and see you. I can only pray God to bless you—and help me."[220] Venetia's importance to him is illustrated by a remark in a letter written in mid-1914: "Keep close to me beloved in this most critical time of my life. I know you will not fail."[221] Her engagement, "a very treacherous return after all the joy you've given me", left him devastated.[222] Significant though the loss was personally, its impact on Asquith politically can be overstated.[223] The historian Stephen Koss notes that Asquith "was always able to divide his public and private lives into separate compartments (and) soon found new confidantes to whom he was writing with no less frequency, ardour and indiscretion."[224]

This personal loss was immediately followed, on 15 May, by the resignation of Admiral Fisher after continuing disagreements with Churchill and in frustration at the disappointing developments in Gallipoli.[225] Aged 74, Fisher's behaviour had grown increasingly erratic and, in frequent letters to Lloyd George, he gave vent to his frustrations with the First Lord of the Admiralty: "Fisher writes to me every day or two to let me know how things are going. He has a great deal of trouble with his chief, who is always wanting to do something big and striking."[226] Adverse events, press hostility, Conservative opposition and personal sorrows assailed Asquith, and his position was further weakened by his Liberal colleagues. Cassar considers that Lloyd George displayed a distinct lack of loyalty,[227] and Koss writes of the contemporary rumours that Churchill had "been up to his old game of intriguing all round" and reports a claim that Churchill "unquestionably inspired" the Repington Letter, in collusion with Sir John French.[228] Lacking cohesion internally, and attacked from without, Asquith determined that his government could not continue and he wrote to the King, "I have come decidedly to the conclusion that the [Government] must be reconstituted on a broad and non-party basis."[229]

First Coalition: May 1915 – December 1916

The formation of the First Coalition saw Asquith display the political acuteness that seemed to have deserted him.[230] But it came at a cost. This involved the sacrifice of two old political comrades: Churchill, who was blamed for the Dardanelles fiasco, and Haldane, who was wrongly accused in the press of pro-German sympathies.[229] The Conservatives under Bonar Law made these removals a condition of entering government and, in sacking Haldane, who "made no difficulty",[231] Asquith, committed "the most uncharacteristic fault of (his) whole career".[232] In a letter to Grey, Asquith wrote of Haldane, "He is the oldest personal and political friend that I have in the world and, with him, you and I have stood together for the best part of 30 years."[233] But he was unable to express these sentiments directly to Haldane, who was greatly hurt. Asquith handled the allocation of offices more successfully, appointing Law to the relatively minor post of Colonial Secretary,[234] taking responsibility for munitions from Kitchener and giving it, as a new ministry, to Lloyd George and placing Balfour at the Admiralty, in place of Churchill, who was demoted to the sinecure Cabinet post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Overall the Liberals held 12 Cabinet seats, including most of the important ones, while the Conservatives held 8.[235] Despite this outcome, many Liberals were dismayed, the sacked Charles Hobhouse writing, "The disintegration of the Liberal Party is complete. Ll.G. and his Tory friends will soon get rid of Asquith."[236] From a party, and a personal, perspective, the creation of the First Coalition was seen as a "notable victory for (Asquith), if not for the allied cause".[230] But Asquith's dismissive handling of Law also contributed to his own and his party's later destruction.[237]

War re-organisation

Having reconstructed his government, Asquith attempted a re-configuration of his war-making apparatus. The most important element of this was the establishment of the Ministry of Munitions,[238] followed by the re-ordering of the War Council into a Dardanelles Committee, with Maurice Hankey as secretary and with a remit to consider all questions of war strategy.[239]

The Munitions of War Act 1915 brought private companies supplying the armed forces under the tight control of the Minister of Munitions, Lloyd George. The policy, according to J. A. R. Marriott, was that:

no private interest was to be permitted to obstruct the service, or imperil the safety, of the State. Trade Union regulations must be suspended; employers' profits must be limited, skilled men must fight, if not in the trenches, in the factories; man-power must be economised by the dilution of labour and the employment of women; Private factories must pass under the control of the State, and new national factories be set up. Results justified the new policy: the output was prodigious; the goods were at last delivered.[240]

Nevertheless, criticism of Asquith's leadership style continued. The Earl of Crawford, who had joined the Government as Minister of Agriculture, described his first Cabinet meeting in these terms: "It was a huge gathering, so big that it is hopeless for more than one or two to express opinions on each detail [...] Asquith somnolent—hands shaky and cheeks pendulous. He exercised little control over debate, seemed rather bored, but good humoured throughout." Lloyd George was less tolerant, George Riddell recording in his diary, "(He) says the P.M. should lead not follow and (Asquith) never moves until he is forced, and then it is usually too late."[241] And crises, as well as criticism, continued to assail the Prime Minister, "envenomed by intra-party as well as inter-party rancour".[242]

Conscription

The insatiable demand for manpower for the Western Front had been foreseen early on. A volunteer system had been introduced at the outbreak of war, and Asquith was reluctant to change it for political reasons, as many Liberals, and almost all of their Irish Nationalist and Labour allies, were strongly opposed to conscription.[243] Volunteer numbers dropped,[244] not meeting the demands for more troops for Gallipoli, and much more strongly, for the Western Front.[245] This made the voluntary system increasingly untenable; Asquith's daughter Violet wrote in March 1915, "Gradually every man with the average number of limbs and faculties is being sucked out to the war."[246] In July 1915, the National Registration Act was passed, requiring compulsory registration for all men between the ages of 18 and 65.[247] This was seen by many as the prelude to conscription but the appointment of Lord Derby as Director-General of Recruiting instead saw an attempt to rejuvenate the voluntary system, the Derby Scheme.[248] Asquith's slow steps towards conscription continued to infuriate his opponents. Sir Henry Wilson, for example, wrote this to Leo Amery: "What is going to be the result of these debates? Will 'wait and see' win, or can that part of the Cabinet that is in earnest and is honest force that damned old Squiff into action?"[249] The Prime Minister's balancing act, within Parliament and within his own party, was not assisted by a strident campaign against conscription conducted by his wife. Describing herself as "passionately against it",[250] Margot Asquith engaged in one of her frequent influencing drives, by letters and through conversations, which had little impact other than doing "great harm" to Asquith's reputation and position.[251]