Henry Flagler

Henry Flagler | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Henry Flagler | |

| Born | Henry Morrison Flagler January 2, 1830 Hopewell, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 20, 1913 (aged 83) Palm Beach, Florida, U.S. |

| Resting place | Memorial Presbyterian Church, St. Augustine, Florida, U.S. |

| Children | 3, including Harry Harkness Flagler |

Henry Morrison Flagler (January 2, 1830 – May 20, 1913) was an American industrialist and a founder of Standard Oil, which was first based in Ohio. He was also a key figure in the development of the Atlantic coast of Florida and founder of the Florida East Coast Railway. He is also known as a co-founder and major investor of the cities of Miami and Palm Beach, Florida.[1]

Early life and education

Flagler was born in Hopewell, New York. His father was Isaac Flagler, a Presbyterian minister and great-grandson of Zacharra Flegler, whose family had emigrated from the German Palatinate region to Holland in 1688. Zacharra worked in England for several years before moving to Dutchess County, New York, in 1710. His grandson Solomon changed the spelling of the surname to Flagler and passed it on to his 11 children.[2] Flagler's mother was Elizabeth Caldwell Harkness Flagler, Isaac's third wife and a widow who had a stepson, Stephen V. Harkness, and a son, Daniel M. Harkness, from her marriage to deceased widower David Harkness of Milan, Ohio.[3]

Flagler attended local schools through eighth grade. His half-brother Daniel had left Hopewell to live and work with his paternal uncle Lamon G. Harkness, who had a store in Republic, Ohio. He recruited Henry Flagler to join him, and the youth went to Ohio at age 14, where he started work in 1844 at a salary of US$5 per month plus room and board. By 1849, Flagler was promoted to the sales staff at a salary of $40 per month. He later joined Daniel in a grain business started with his uncle Lamon in Bellevue, Ohio, [citation needed] and made a small fortune distilling whiskey. He sold his stake in the business in 1858.[4]

In 1862, Flagler and his wife's brother-in-law Barney Hamlin York (1833–1884) founded the Flagler and York Salt Company, a salt mining and production business in Saginaw, Michigan. He found that salt mining required more technical knowledge than he had and struggled in the industry during the Civil War. The company collapsed when the war undercut commercial demand for salt. Flagler returned to Bellevue having lost his initial $50,000 investment and an additional $50,000 he had borrowed from his father-in-law and Daniel. Flagler believed that he had learned a valuable lesson: invest in a business only after thorough investigation.[5]

Business and Standard Oil

After the failure of his salt business in Saginaw, Flagler returned to Bellevue in 1866 and reentered the grain business as a commission merchant with the Harkness Grain Company. During this time he worked to pay back his stepbrother. Through this business, Flagler became acquainted with John D. Rockefeller, who worked as a commission agent with Hewitt and Tuttle for the Harkness Grain Company. By the mid-1860s, Cleveland had become the center of the oil refining industry in America and Rockefeller left the grain business to start his own oil refinery. Rockefeller worked in association with chemist and inventor Samuel Andrews.[citation needed]

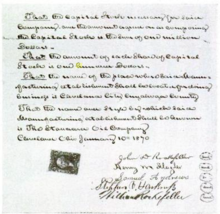

Needing capital for his new venture, Rockefeller approached Flagler in 1867. Flagler's stepbrother Stephen V. Harkness invested $100,000 (equivalent to $2.18 million in 2023[7]) on the condition that Flagler be made a partner. The Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler partnership was formed with Flagler in control of Harkness' interest.[8] The partnership eventually grew into the Standard Oil Corporation. It was Flagler's idea to use the rebate system to strengthen the firm's position against competitors and the transporting enterprises alike. Flagler was in a special position to make those deals due to his connections as a grain merchant. Equivalent to a 15% discount, they put Standard Oil in position to significantly undercut other oil refineries.[9] By 1872, it led the American oil refining industry, producing 10,000 barrels per day (1,600 m3/d). In 1877, Flagler and his family moved to New York City, which was becoming the center of commerce in the U.S.. In 1885, Standard Oil moved its corporate headquarters to New York City to the iconic 26 Broadway location.[citation needed]

By the end of the American Civil War, Cleveland was one of the five main refining centers in the U.S. (besides Pittsburgh, New York City, Philadelphia, and the region in northwestern Pennsylvania where most of the oil originated).[10]

By 1869, there was three times more kerosene refining capacity than needed to supply the market, and the capacity remained in excess for many years.[11] In June 1870, Flagler and Rockefeller formed Standard Oil of Ohio, which rapidly became the most profitable refiner in Ohio. Standard Oil grew to become one of the largest shippers of oil and kerosene in the country. The railroads were fighting fiercely for traffic and, in an attempt to create a cartel to control freight rates, formed the South Improvement Company in collusion with Standard and other oil men outside the main oil centers.[12] The cartel received preferential treatment as a high-volume shipper, which included not just steep rebates of up to 50% for their product but also rebates for the shipment of competing products.[12] Part of this scheme was the announcement of sharply increased freight charges. This touched off a firestorm of protest from independent oil well owners, including boycotts and vandalism, which eventually led to the discovery of Standard Oil's part in the deal. A major New York refiner, Charles Pratt and Company, headed by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers, led the opposition to this plan, and railroads soon backed off. Pennsylvania revoked the cartel's charter, and non-preferential rates were restored for the time being.[13]

Undeterred, though vilified for the first time by the press, Flagler and Rockefeller continued with their self-reinforcing cycle of buying competing refiners, improving the efficiency of operations, pressing for discounts on oil shipments, undercutting competition, making secret deals, raising investment pools, and buying rivals out. In less than four months in 1872, in what was later known as "The Cleveland Conquest" or "The Cleveland Massacre", Standard Oil had absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors.[14] Eventually, even former antagonists Pratt and Rogers saw the futility of continuing to compete against Standard Oil: in 1874, they made a secret agreement with their old nemesis to be acquired. Pratt and Rogers became Flagler and Rockefeller's partners. Rogers, in particular, became one of Flagler and Rockefeller's key men in the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt, became Secretary of Standard Oil. For many of the competitors, Flagler and Rockefeller had merely to show them the books so they could see what they were up against and make them a decent offer. If they refused the offer, Flagler and Rockefeller told them they would run them into bankruptcy and then cheaply buy up their assets at auction. Flagler and Rockefeller saw themselves as the industry's saviors, "an angel of mercy" absorbing the weak and making the industry as a whole stronger, more efficient, and more competitive.[15] Standard was growing horizontally and vertically. It added its own pipelines, tank cars, and home delivery network. It kept oil prices low to stave off competitors, made its products affordable to the average household, and, to increase market penetration, sometimes sold below cost if necessary. It developed over 300 oil-based products from tar to paint to Vaseline petroleum jelly to chewing gum. By the end of the 1870s, Standard was refining over 90% of the oil in the U.S.[16]

In 1877, Standard clashed with Thomas A. Scott the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, its chief hauler. Flagler and Rockefeller had envisioned the use of pipelines as an alternative transport system for oil and began a campaign to build and acquire them.[17] The railroad, seeing Standard's incursion into the transportation and pipeline fields, struck back and formed a subsidiary to buy and build oil refineries and pipelines.[18]This subsidiary, the Empire Transportation Company, which Joseph D. Potts created in 1865 and also ran, owned other assets including a small fleet of ships on the Great Lakes.[19][20] Standard countered and held back its shipments and, with the help of other railroads, started a price war that dramatically reduced freight payments and caused labor unrest as well. Flagler and Rockefeller eventually prevailed and the railroad sold all its oil interests to Standard. But in the aftermath of that battle, in 1879 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania indicted Flagler and Rockefeller on charges of monopolizing the oil trade, starting an avalanche of similar court proceedings in other states and making a national issue of Standard Oil's business practices.[21] The New York State Legislature's Hepburn Committee in 1879 conducted hearings in response to the complaints of local merchants that were not involved in the oil trade in order to investigate railroad rebate practices. The committee ultimately discovered the previously unknown scope of Standard Oil's business interests.[22]

Monopoly

Standard Oil gradually gained almost complete control of oil refining and marketing in the United States through horizontal integration. In the kerosene industry, Standard Oil replaced the old distribution system with its own vertical system. It supplied kerosene by tank cars that brought the fuel to local markets, and tank wagons then delivered to retail customers, thus bypassing the existing network of wholesale jobbers.[23] Despite improving the quality and availability of kerosene products while greatly reducing their cost to the public (the price of kerosene dropped by nearly 80% over the life of the company), Standard Oil's business practices created intense controversy. Standard's most potent weapons against competitors were underselling, differential pricing, and secret transportation rebates.[24] The firm was attacked by journalists and politicians throughout its existence, in part for these monopolistic methods, giving momentum to the antitrust movement. By 1880, according to the New York World, Standard Oil was "the most cruel, impudent, pitiless, and grasping monopoly that ever fastened upon a country."[25] To the critics Flagler and Rockefeller replied, "In a business so large as ours... some things are likely to be done which we cannot approve. We correct them as soon as they come to our knowledge."[25]

At that time, many legislatures had made it difficult to incorporate in one state and operate in another. As a result, Flagler and Rockefeller and their associates owned dozens of separate corporations, each of which operated in just one state; the management of the whole enterprise was rather unwieldy. In 1882, Flagler and Rockefeller's lawyers created an innovative form of corporation to centralize their holdings, giving birth to the Standard Oil Trust.[26] The "trust" was a corporation of corporations, and the entity's size and wealth drew much attention. Nine trustees, including Rockefeller, ran the 41 companies in the trust.[26] The public and the press were immediately suspicious of this new legal entity, and other businesses seized upon the idea and emulated it, further inflaming public sentiment. Standard Oil had gained an aura of invincibility, always prevailing against competitors, critics, and political enemies. It had become the richest, biggest, most feared business in the world, seemingly immune to the boom and bust of the business cycle, consistently racking up profits year after year.[27]

Its vast American empire included 20,000 domestic wells, 4,000 miles of pipeline, 5,000 tank cars, and over 100,000 employees.[27] Its share of world oil refining topped out above 90% but slowly dropped to about 80% for the rest of the century.[28] In spite of the formation of the trust and its perceived immunity from all competition, by the 1880s Standard Oil had passed its peak of power over the world oil market. Flagler and Rockefeller finally gave up their dream of controlling all the world's oil refining. Rockefeller admitted later, "We realized that public sentiment would be against us if we actually refined all the oil."[28] Over time foreign competition and new finds abroad eroded his dominance. In the early 1880s, Flagler and Rockefeller created one of their most important innovations. Rather than try to influence the price of crude oil directly, Standard Oil had been exercising indirect control by altering oil storage charges to suit market conditions. Flagler and Rockefeller then decided to issue certificates against oil stored in Standard Oil's pipelines. These certificates became traded by speculators, thus creating the first oil-futures market which effectively set spot market prices from then on. The National Petroleum Exchange opened in Manhattan in late 1882 to facilitate the oil futures trading.[29]

Even though 85% of world crude production was still coming from Pennsylvania wells in the 1880s, overseas drilling in Russia and Asia began to reach the world market.[30] Robert Nobel had established his own refining enterprise in the abundant and cheaper Russian oil fields, including the region's first pipeline and the world's first oil tanker. The Paris Rothschilds jumped into the fray providing financing.[31] Additional fields were discovered in Burma and Java. Even more critical, the invention of the light bulb gradually began to erode the dominance of kerosene for illumination. But Standard Oil adapted, developing its own European presence, expanding into natural gas production in the U.S., then into gasoline for automobiles, which until then had been considered a waste product.[32]

Standard Oil moved its headquarters to New York City, at 26 Broadway, and Flagler and Rockefeller became central figures in the city's business community. In 1887, Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission, which was tasked with enforcing equal rates for all railroad freight, but by then Standard depended more on pipeline transport.[33] More threatening to Standard's power was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, originally used to control unions, but later central to the breakup of the Standard Oil trust.[34] Ohio was especially vigorous in applying its state anti-trust laws, and finally forced a separation of Standard Oil of Ohio from the rest of the company in 1892, the first step in the dissolution of the trust.[34]

Upon his ascent to the presidency, Theodore Roosevelt initiated dozens of suits under the Sherman Antitrust Act and coaxed reforms out of Congress. In 1901, U.S. Steel, now controlled by J. Pierpont Morgan, having bought Andrew Carnegie's steel assets, offered to buy Standard's iron interests as well. A deal brokered by Henry Clay Frick exchanged Standard's iron interests for U.S. Steel stock and gave Rockefeller and his son membership on the company's board of directors.[citation needed]

One of the most effective attacks on Flagler and Rockefeller and their firm was the 1905 publication of The History of the Standard Oil Company, by Ida Tarbell, a leading muckraker. She documented the company's espionage, price wars, heavy-handed marketing tactics, and courtroom evasions.[35] Although her work prompted a huge backlash against the company, Tarbell claims to have been surprised at its magnitude. "I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and wealthy as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me." Tarbell's father had been driven out of the oil business during the South Improvement Company affair.[citation needed]

Flagler and Rockefeller began a publicity campaign to put the company and themselves in a better light. Though Flagler and Rockefeller had long maintained a policy of active silence with the press, they decided to make themselves more accessible and responded with conciliatory comments such as "capital and labor are both wild forces which require intelligent legislation to hold them in restriction."[36]

Flagler and Rockefeller continued to consolidate their oil interests as best they could until New Jersey, in 1909, changed its incorporation laws to effectively allow a re-creation of the trust in the form of a single holding company. Rockefeller retained his nominal title as president until 1911 and he kept his stock. At last in 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States found Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. By then the trust still had a 70% market share of the refined oil market but only 14% of the U.S. crude oil supply.[37] The court ruled that the trust originated in illegal monopoly practices and ordered it to be broken up into 34 new companies. These included, among many others, Continental Oil, which became Conoco, now part of ConocoPhillips; Pennzoil, now part of Shell;[38] Standard of Indiana, which became Amoco, now part of BP; Standard of California, which became Chevron, still a separate company; Standard of New Jersey, which became Esso (and later, Exxon), now part of ExxonMobil; Standard of New York, which became Mobil, now part of ExxonMobil; and Standard of Ohio, which became Sohio, now part of BP.[39]

Flagler's contributions

When Flagler envisioned successes in the oil industry, he and Rockefeller started building their fortune in refining oil in Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland became very well known for oil refining, as, "More and more crude oil was shipped from the oil regions to Cleveland for the refining process because of transportation facilities and the aggressiveness of the refiners there. It was due largely to the efforts of Henry M. Flagler and John D. Rockefeller."[40] Flagler and Rockefeller worked hard for their company to achieve such prominence. Henry explained: "We worked night and day, making good oil as cheaply as possible and selling it for all we could get."[41] Not only did Flagler and Rockefeller's Standard Oil company become well known in Ohio, they expanded to other states, as well as gained additional capital in purchasing smaller oil refining companies across the nation.[41] According to Allan Nevins, in John D. Rockefeller (p 292), "Standard Oil was born as a big enterprise, it had cut its teeth as a partnership and was now ready to plunge forward into a period of greater expansion and development. It soon was doing one tenth of all the petroleum business in the United States. Besides its two refineries and a barrel plant in Cleveland, it possessed a fleet of tank cars and warehouses in the oil regions as well as warehouses and tanks in New York."[42]

By 1892, Standard Oil had a monopoly over all oil refineries in the United States. In an overall calculation of America's oil refineries' assets and capital, Standard Oil surpassed all.[43] Standard Oil's combined assets equalled approximately $42,882,650 (equivalent to $1.45 billion in 2023[7]) in Indiana, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York and Ohio. Standard Oil also had the highest capitalization, totaling $26,000,000 (equivalent to $882 million in 2023).[43]

Although Standard Oil was a partnership, Flagler was credited as the brain behind the booming oil refining business. "When John D. Rockefeller was asked if the Standard Oil company was the result of his thinking, he answered, 'No, sir. I wish I had the brains to think of it. It was Henry M. Flagler.'"[44] Flagler served as an active part of Standard Oil until 1882, when he stepped back to take a secondary role at Standard Oil. He served as a vice president through 1908 and was part of ownership until 1911.[45]

Florida: resort hotels and railroads

When Flagler's first wife Mary (née Harkness) fell sick, his physician recommended they travel to Jacksonville for the winter to escape the brutal conditions of the North. For the first time, Flagler was able to experience the warm, sunny atmosphere of Florida. Two years after his first wife died in 1881, he married again. Ida Alice (née Shourds) Flagler had been a caregiver for Mary. After their wedding, the couple traveled to Saint Augustine. Flagler found the city charming, but the hotel facilities and transportation systems inadequate. Franklin W. Smith had just finished building Villa Zorayda and Flagler offered to buy it for his honeymoon. Smith would not sell, but he planted the seed of St. Augustine's and Florida's future in Flagler's mind.[46]

Although Flagler remained on the board of directors of Standard Oil, he gave up his day-to-day involvement in the corporation to pursue his interests in Florida. He returned to St. Augustine in 1885 and made Smith an offer. If Smith could raise $50,000, Flagler would invest $150,000 and they would build a hotel together. Perhaps fortunately for Smith, he couldn't come up with the funds,[47] so Flagler began construction of the 540-room Ponce de Leon Hotel by himself, but spent several times his original estimate. Smith helped train the masons on the mixing and pouring techniques he used on Zorayda.[48]

Realizing the need for a sound transportation system to support his hotel ventures, Flagler purchased short line railroads in what would later become known as the Florida East Coast Railway. He used convict leasing — "a method undertaken by the Southern States to replace the economic setup of slavery"[49] — to modernize the existing railroads, allowing them to accommodate heavier loads and more traffic.[50]

His next project was the Ponce de Leon Hotel, now part of Flagler College. He invested with the guidance of Dr. Andrew Anderson, a native of St. Augustine. After many years of work, it opened on January 10, 1888, and was an instant success.

This project sparked Flagler's interest in creating a new "American Riviera." Two years later, he expanded his Florida holdings. He built a railroad bridge across the St. Johns River to gain access to the southern half of the state and purchased the Hotel Ormond, just north of Daytona. He also built the Alcazar Hotel as an overflow hotel for the Ponce de Leon Hotel. The Alcazar is today the Lightner Museum, next to the Casa Monica Hotel in St. Augustine that Flagler bought from Franklin W. Smith. His personal dedication to the state of Florida was demonstrated when he began construction on his private residence, Kirkside, in St. Augustine.

An immense engineering effort was required to cut through the wilderness and marsh from St. Augustine to Palm Beach. The state provided incentive in the form of 3,840 acres (15.5 km2) for every mile (1.6 km) of track constructed.[51]

Flagler completed the 1,100-room Royal Poinciana Hotel on the shores of Lake Worth in Palm Beach and extended his railroad to its service town, West Palm Beach, by 1894, founding Palm Beach and West Palm Beach.[1] The Royal Poinciana Hotel was at the time the largest wooden structure in the world. Two years later, Flagler built the Palm Beach Inn (renamed The Breakers in 1901), overlooking the Atlantic Ocean in Palm Beach.

Flagler originally intended West Palm Beach to be the terminus of his railroad system, but in 1894 and 1895, severe freezes hit the area, causing Flagler to reconsider. Sixty miles (97 km) south, the area today known as Miami was reportedly unharmed by the freeze. To further convince Flagler to continue the railroad to Miami, he was offered land in exchange for laying rail tracks from private landowners, the Florida East Coast Canal and Transportation Company, and the Boston and Florida Atlantic Coast Land Company. The land owners were Julia Tuttle, whom he had met in Cleveland, Ohio, and William Brickell, who ran a trading post on the Miami River.

Such incentive led to the development of Miami, which was an unincorporated area at the time. Flagler encouraged fruit farming and settlement along his railway line and made many gifts to build hospitals, churches and schools in Florida.[citation needed]

By 1896, Flagler's railroad, the Florida East Coast Railway, reached Biscayne Bay. Flagler dredged a channel, built streets, instituted the first water and power systems, and financed the city's first newspaper, The Metropolis. When the city was incorporated in 1896, its citizens wanted to honor the man responsible for its growth by naming it "Flagler". He declined the honor, persuading them to use an old Indian name, "Mayaimi". Instead, an artificial island was constructed in Biscayne Bay called Flagler Monument Island. In 1897, Flagler opened the exclusive Royal Palm Hotel on the north bank of the Miami River where it overlooked Biscayne Bay. He became known as the Father of Miami, Florida.

Flagler's second wife, the former Ida Alice Shourds, was declared insane[52] by Flagler's friend Dr. Anderson in 1896 and was institutionalized on and off starting that year. At the same time, he began to have an affair with Mary Lily Kenan; by 1899, newspapers began to openly question whether the two were having an affair. That year he reportedly gave her more than $1 million in jewelry.[53] In 1901, Flagler bribed the Florida Legislature and Governor to pass a law that made incurable insanity grounds for divorce, opening the way for Flagler to remarry. Flagler was the only person to be divorced under the law before it was repealed in 1905.[54] It was not until 1969 that a spouse's incurable insanity (mental incapacity) again became a ground for divorce in Florida.[55] It remains a ground today,[56] but since Florida became a "no fault" divorce state in 1971,[57] there is less need to use that ground to obtain a divorce (dissolution of marriage).

On August 24, 1901, 10 days after his divorce, Flagler married Mary Lily at her family's plantation, Liberty Hall, and the couple soon moved into their new Palm Beach estate, Whitehall, a 55-room beaux arts home designed by the New York-based firm of Carrère and Hastings, which also had designed the New York Public Library and the Pan-American Exposition.[58] Built in 1902 as a wedding present to Mary Lily, Whitehall (now the Flagler Museum) was a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) winter retreat that established the Palm Beach "season" of about 8–12 weeks, for the wealthy of America's Gilded Age.[citation needed]

By 1905, Flagler decided that his Florida East Coast Railway should be extended from Biscayne Bay to Key West, a point 128 miles (206 km) past the end of the Florida peninsula. At the time, Key West was Florida's most populous city, with a population of 20,000, and it was also the United States' deep water port closest to the canal that the U.S. government proposed to build in Panama. Flagler wanted to take advantage of additional trade with Cuba and Latin America as well as the increased trade with the west that the Panama Canal would bring.[citation needed]

In 1912, the Florida Overseas Railroad was completed to Key West. Over 30 years, Flagler had invested about $50 million in railroad, home and hotel construction and had made donations to suffering farmers after the freeze in 1894. When asked by the president of Rollins College in Winter Park about his philanthropic efforts, Flagler reportedly replied, "I believe this state is the easiest place for many men to gain a living. I do not believe any one else would develop it if I do not..., but I do hope to live long enough to prove I am a good business man by getting a dividend on my investment."[59]

Alleged use of convict leasing and debt peonage

Flagler allegedly used convicts leased from Florida prison camps, the majority of them African-American, to clear land for the Royal Palm Hotel in Miami and to build the Florida East Coast Railway from West Palm Beach to Miami and the rail extension to Key West. He also used labor agencies to bring around 4,000 new immigrants to Florida who contracted to work until their transportation costs had been paid off. Due to the harsh working and living conditions in the railway construction camps, many workers became victims of debt slavery.[60][61]

When the Department of Justice prosecuted four Flagler employment agents in 1908 for "conspiracy to hold workmen in peonage and slavery," the Flagler-owned The Florida Times-Union and other Florida newspapers depending on the Times-Union for material or owned by Flagler published articles to "influence juries and public opinion." The judge instructed the jury to find them not guilty because the "prosecution had failed to prove 'an agreement of minds with evil intent to conspire'."[60]

A congressional investigation in 1909 concluded that "there had been little immigrant peonage in the South and none in the ... [railway camps] camps in the Keys. Congress concluded that newspapers in Florida and across the South spread the deceitful news against Flagler."[61][62]

According to historian Joe Knetsch, reformers and muckrakers exaggerated charges of peonage regarding construction of the Florida East Coast Railway in 1893 to 1909. Flager and his lawyers defeated all legal challenges and neither the company or its employees were ever convicted in court. However, there were many reports of harsh working conditions and forced indebtedness to the company, and malfeasance by labor agents who hired men for the railway. Knetsch concludes that "Flagler in fact provided health care for his employees and was a far better employer than the press alleged."[63]

Death and legacy

In March 1913, Flagler fell down a flight of marble stairs at Whitehall. He never recovered and died in Palm Beach of his injuries on May 20, 1913, at 83 years of age.[64][65] At 3 p.m. on the day of the funeral, May 23, 1913, every engine on the Florida East Coast Railway stopped wherever it was for ten minutes as a tribute to Flagler. It was reported that people along the railway line waited all night for the passing of the funeral train as it traveled from Palm Beach to St. Augustine.[66]

Flagler was entombed in the Flagler family mausoleum at Memorial Presbyterian Church in St. Augustine alongside his first wife, Mary Harkness; daughter, Jennie Louise (née Flagler) Benedict; and granddaughter, Margery [Benedict].[67] Only his son Harry Harkness Flagler survived of the three children by his first marriage in 1853 to Mary Harkness. A large portion of his estate was designated for a "niece" who was said actually to be a child born out of wedlock.[citation needed]

When looking back at Flagler's life, after Flagler's death, George W. Perkins, of J.P. Morgan & Co., reflected, "But that any man could have the genius to see of what this wilderness of waterless sand and underbrush was capable and then have the nerve to build a railroad here, is more marvelous than similar development anywhere else in the world."[68]

Miami's main east–west street is named Flagler Street and is the main shopping street in Downtown Miami. Flagler Avenue is a main route through Key West. There is also a monument to him on Flagler Monument Island in Biscayne Bay in Miami; Flagler College and Flagler Hospital are named after him in St. Augustine. Flagler County, Florida, Flagler Beach, Florida, and Flagler, Colorado, are also named for him. Whitehall, Palm Beach, is open to the public as the Henry Morrison Flagler Museum; his private railcar No. 91 is preserved inside a Beaux Arts pavilion built to look like a 19th-century railway palace.[69]

On February 24, 2006, a statue of Flagler was unveiled in Key West near the spot where the Overseas Railroad once terminated. Also, on July 28, 2006, a statue of Flagler was unveiled on the southeast steps of Miami's Dade County Courthouse, located on Miami's Flagler Street.[citation needed]

The Overseas Railroad, also known as the Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway, was heavily damaged and partially destroyed in the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. The railroad was financially unable to rebuild the destroyed sections, so the roadbed and remaining bridges were sold to the State of Florida, which built the Overseas Highway to Key West, using much of the remaining railway infrastructure.[citation needed]

Flagler's third wife, Mary Lily Kenan Flagler Bingham was born in North Carolina. The top-ranked Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is named for Flagler and his wife, who was an early benefactor of UNC along with her family and descendants.[70] After Flagler's death, she married an old friend, Robert Worth Bingham, who used an inheritance from her to buy the Louisville Courier-Journal. The Bingham-Flagler marriage (and questions about her death or possible murder) figured prominently in several books that appeared in the 1980s, when the Bingham family sold the newspaper in the midst of great acrimony. Control of the Flagler fortune largely passed into the hands of Mary Lily Kenan's family of sisters and brother, who survived into the 1960s.[citation needed][71]

See also

- Casa Monica Hotel - purchased by Flagler and renamed Cordova

- Ponce de León Hotel - Built by Flagler

- The Alcazar Hotel now the Lightner Museum

- Flagler Memorial Presbyterian Church St. Augustine, FL

- Royal Poinciana Hotel

- Whitehall now Henry Morrison Flagler Museum

- Breakers Hotel

References

- ^ a b "Madoff scandal stuns Palm Beach Jewish community". Reuters. December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Henry Morrison Flagler - S. Walter Martin

- ^ Martin 1949. 05.

- ^ Yergin, Daniel (2008). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (Third ed.). Free Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4391-1012-6.

- ^ Martin. 29.

- ^ Udo Hielscher. Historische amerikanische Aktien, p. 68 - 74, ISBN 3921722063

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Martin. p. 45.

- ^ Martin. p. 64.

- ^ Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- ^ Yergin, Daniel (1992). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-1012-6.

- ^ a b Segall (2001), p. 42.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 43.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 44.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 46.

- ^ Segall (2001), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 57.

- ^ "292: Colonel Joseph D. Potts Leader in the Pennsylvania on LiveAuctioneers".

- ^ Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. p. 109. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 58.

- ^ Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. pp. 145-150. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 258.

- ^ a b Segall (2001), p. 60.

- ^ a b Segall (2001), p. 61.

- ^ a b Chernow 1998, p. 249.

- ^ a b Segall (2001), p. 67.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 259.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 242.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 246.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 68.

- ^ Rockefeller 1984, p. 48.

- ^ a b Segall (2001), p. 69.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 89.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 91.

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 93.

- ^ Pennzoil Company, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Segall (2001), p. 112.

- ^ Martin, Sidney Walter. Florida's Flagler. Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2010, p. 55.

- ^ a b Sammons, Sandra Wallus. Henry Flagler, Builder of Florida. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press Inc, 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Martin, p. 58.

- ^ a b Tarbell (1905), p. 376.

- ^ Martin, p. 56, quoting Edwin Lefevre, in "Flagler and Florida" from Everybody's Magazine, XXII (February 1910) p. 183.

- ^ Chandler (1986), p. 92-93.

- ^ Nolan (1984), p. 95.

- ^ Nolan (1984), p. 101.

- ^ Nolan (1984), p. 105.

- ^ "The Story of Convict Leasing in Florida". www.thejaxsonmag.com. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ "Henry M. Flagler | American financier". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Eriksen, John M. Brevard County, Florida : A Short History to 1955. Chapter Eight

- ^ Stone, Rick (February 13, 2005). "Robber Baron in Love". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Chandler (1986), p. 168-172.

- ^ "Divorce Law Was For One Person". The Ledger. March 28, 2010. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Fla. Laws ch. 69-142.

- ^ Fla. Stat. s. 61.052(1)(b)

- ^ Fla. Laws ch. 71-241

- ^ Chandler (1986), p. 193.

- ^ Chandler (1986).

- ^ a b Carper, N. Gordon (January 1, 1976). "Slavery Revisited: Peonage in the South". Phylon. 37 (1): 90–92. doi:10.2307/274733. JSTOR 274733. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Bowman, Bryan; Roberts Forde, Kathy (May 17, 2018). "How slave labor built the state of Florida — decades after the Civil War". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Abstracts of Reports of the Immigration Commission, Vol II". Washington Government Printing Office. 1911. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Joe Knetsch, "The Peonage Controversy and the Florida East Coast Railway," Tequesta (1999), Vol. 59, pp 5-28.

- ^ "Whitehall Flagler Museum". Destination 360. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ "Henry Morrison Flagler". Everglades Digital Library. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ ""News of Henry Flagler's death rediscovered years later; Descendants of Marie Smith find rare copy of The Record reporting benefactor's funeral" The St. Augustine Record, Nov. 14, 2011". Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Henry Flagler". St. Augustine Record. May 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ Moffet, Samuel. Henry Morrison Flagler The Cosmopolitan; a Monthly Illustrated Magazine (1902) APS Online

- ^ "Henry Morrison Flagler Museum". Fodor's. May 12, 2014.

- ^ "History". Kenan-Flagler Business School. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Walter E. Campbell, Across Fortune’s Tracks: A Biography of William Rand Kenan, Jr. (UNC Press, 1996)

Bibliography

- Chandler, David Leon (1986). Henry Flagler: The Astonishing Life and Times of the Visionary Robber Baron who Founded Florida. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 9780025236905.

- Chernow, Ron (1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. London: Warner Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-7730-4.

- Derbyshire, Wyn (2008). Six Tycoons: The lives of John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford and Joseph P. Kennedy. London: Spiramus Press. ISBN 978-1-9049-0585-1. OCLC 231588563.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- Knetsch, Joe. "The Peonage Controversy and the Florida East Coast Railway," Tequesta (1999), Vol. 59, pp 5–28.

- Martin, Sidney Walter (1998). Henry Flagler Visionary of the Gilded Age. Tailored Tours Publications, Buena Vista, Florida. ISBN 0-9631241-1-0.

- Martin, Sydney Walter (1949). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press, USA.

- Rockefeller, John D. (1984) [1909]. Random Reminiscences of Men and Events. New York: Sleepy Hollow Press and Rockefeller Archive Center. ISBN 978-1-79049-499-6.

- Segall, Grant (February 8, 2001). John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19512147-6. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Standiford, Les (2002). Last Train to Paradise. Crown Publishers, New York. ISBN 0-609-60748-0.

- Tarbell, Ida M. (1905). The History of the Standard Oil Company. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co.

Further reading

- Akin, Edward N. (1991). Flagler: Rockefeller Partner and Florida Baron. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1108-6. online

- Bramson, Seth H. (2002). Speedway to Sunshine: The Story of the Florida East Coast Railway. Boston Mills Press, Erin, ONT, Canada. ISBN 1-55046-358-6. Noted by the author as the official history of the Florida East Coast Railway.

- Graham, Thomas. "Henry M. Flagler's Hotel Ponce de León." Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts (1998): 97–111. [

- Graham, Thomas. Mr. Flagler’s St. Augustine (University Press of Florida, 2014), online.

- Keys, Leslee F. Hotel Ponce de Leon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of Flagler’s Gilded Age Palace (University Press of Florida, 2015) online.

- Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996). The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates — A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present. Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8. OCLC 33818143.

- Mendez, Jesus. "1892-A Year of Crucial Decisions in Florida", Florida Historical Quarterly, Summer 2009, Vol. 88 Issue 1, pp 83–106, focus on Flager's aggressive urban development of the city of St. Augustine, his improvement of the local railroad networks between several Florida communities, and negotiations regarding international government trade policies and regulations.

- Nolan, David (1984). Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-1513-0748-7. OCLC 10348448.

- Ossman, Laurie; Ewing, Heather (2011). Carrère and Hastings, The Masterworks. Rizzoli USA. ISBN 9780847835645.

External links

- Henry Flagler biography

- History of The Breakers Hotel

- Flagler College

- Indiana Transportation Museum exhibit of Henry Flagler's private railroad car (Florida East Coast No.90)

- Photo of Flagler and his wife

- Ohio Historical Marker 5-39[permanent dead link] located in Bellevue, Ohio

- Henry Flagler at Find a Grave

- Railroad Bells at A History of Central Florida Podcast