Henry Cow

Henry Cow | |

|---|---|

Henry Cow, 1975 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Cambridge, England |

| Genres | |

| Discography | Henry Cow discography |

| Years active | 1968–1978 |

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Past members |

|

Henry Cow were an English experimental rock group, founded at the University of Cambridge in 1968 by multi-instrumentalists Fred Frith and Tim Hodgkinson. Henry Cow's personnel fluctuated over their decade together, but drummer Chris Cutler, bassist John Greaves, and bassoonist/oboist Lindsay Cooper were important long-term members alongside Frith and Hodgkinson.

An inherent anti-commercial attitude kept them at arm's length from the mainstream music business, enabling them to experiment at will. Critic Myles Boisen writes, "[their sound] was so mercurial and daring that they had few imitators, even though they inspired many on both sides of the Atlantic with a blend of spontaneity, intricate structures, philosophy, and humor that has endured and transcended the 'progressive' tag."[4]

While it was generally thought that Henry Cow took their name from 20th-century American composer Henry Cowell,[7][8] this has been repeatedly denied by band members.[9][10] According to Hodgkinson, the name "Henry Cow" was "in the air" in 1968, and it seemed like a good name for the band. It had no connection to anything.[11][12] In a 1974 interview, Cutler said the name was chosen because "[i]t's silly. What could be sillier than Henry Cow?"[13]

History

Early years

Fred Frith met Tim Hodgkinson, a fellow student, in a blues club at Cambridge University in May 1968. Recognising their mutual open-minded approach to music, the two began performing together, playing a variety of musical styles including "dada blues" and "neo-Hiroshima". One of Henry Cow's first concerts was supporting Pink Floyd at the Architects' Ball at Homerton College, Cambridge, on 12 June 1968.[14]

In October 1968, Henry Cow expanded when they were joined by Andy Powell (bass guitar), David Attwooll (drums)[15] and Rob Brooks (rhythm guitar). They performed with this line-up until December that year, when Frith, Hodgkinson and Powell split off from the rest of the group and became a trio. Powell at the time was studying music at King's College under Roger Smalley, the resident composer. Smalley was influential in Henry Cow's early development. He exposed them to a variety of new music from bands and musicians like Soft Machine, Captain Beefheart and Frank Zappa. Smalley also introduced them to the idea of writing long and complex musical pieces for rock groups.[16] It was at this time that Henry Cow began writing music to challenge their collective ability to play, then using it to improve on themselves.[17][18]

As a trio, with Frith on bass guitar, Powell on drums and Hodgkinson playing an organ that Frith and Powell had persuaded him to learn, Henry Cow performed a number of gigs on the university calendar, including the annual Architects' Ball and the Midsummer Common Festival, as well as a performance on the roof of a 14-storey building in Cambridge. In April 1969, Powell left and the band reverted to a duo, with Frith playing violin and Hodgkinson on keyboards and reeds. In October 1969 philosopher Galen Strawson auditioned for the band. Later, Frith and Hodgkinson persuaded bassist John Greaves to join the band, and with the services of a couple of temporary drummers and then Sean Jenkins, Henry Cow performed as a quartet for the next eight months. In May 1971, Martin Ditcham replaced Jenkins on drums, and with this line-up they played at several events, including the Glastonbury Festival alongside Gong in June 1971.

Ditcham left in July 1971, and it was not until September that year that the drummer's seat was filled again, this time by Chris Cutler. Responding to one of Cutler's adverts in Melody Maker, the band invited him to a rehearsal,[16] and it was only when Cutler joined that Henry Cow settled into a permanent core of Frith, Hodgkinson, Cutler and Greaves. The band then relocated to London, where they began an aggressive rehearsal schedule.

After having entered John Peel's "Rockortunity Knocks" contest in 1971, Henry Cow recorded a John Peel session for BBC Radio 1 in February 1972. They later went on to record another session in October that year and a further three sessions between 1973 and 1975.

In April 1972, Henry Cow wrote and performed the music for Robert Walker's production of Euripides' The Bacchae. This involved an intense and demanding three-week period of concentrated work that changed the band completely. It was during this time that Geoff Leigh on woodwinds joined and Henry Cow became a quintet.

In July 1972, the band performed at the Edinburgh Festival, and wrote and performed music for a ballet with artist Ray Smith and the Cambridge Contemporary Dance Group at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Smith appeared with Henry Cow at several of their early 1970s performances,[14] to "add a dimension to the whole experience".[19] Smith's acts included "set[ting] up an ironing board stage left and spen[ding] the whole evening ... quietly ironing" at the Rainbow Theatre, "read[ing] out short passages of discontinuous text between each piece of music" at the Hammersmith Palais, and miming with a glove puppet at the New London Theatre.[19] Smith later went on to do the "paint sock" art work for three of Henry Cow's LP covers.[20]

Back in London, they started to organise a series of concerts and events under the names Cabaret Voltaire and Explorers' Club at the Kensington Town Hall and the London School of Economics respectively. Invited guests included Derek Bailey, Lol Coxhill, Ivor Cutler, Ron Geesin, David Toop, Lady June and Smith.[14] Improvisers Bailey and Coxhill became "enthusiastic supporters" of Henry Cow and attended many of their concerts; Frith later stated that he was "strongly affected by their critical engagement and encouragement".[21] For the first time the band started getting some attention from the national music press.[22] Reviewing the first Cabaret Voltaire event with Kevin Ayers in October 1972 in New Musical Express, Ian MacDonald described Henry Cow as "one of the most resilient and obstinate of that range of groups normally ignored by the popular music press".[23] This exposure, and a John Peel recording session in April 1973, led to the band signing with Virgin Records in May 1973.[24]

Unrest

Within two weeks of signing the contract, Henry Cow began recording their debut album Legend (also known as Leg End) at Virgin's Manor Studios in Oxfordshire. It took three weeks of hard work, but at the end they were able to handle the studio themselves, which would prove to be invaluable later in their career. The track "Nine Funerals of the Citizen King", sung by the whole group, was Henry Cow's first overtly political statement.[25]

To promote its new signing, Virgin organised a UK tour for Henry Cow and Faust, who had also just signed to the label. During this tour, Henry Cow began preparing music for an unorthodox and provocative play, based on Shakespeare's The Tempest. Some of this music was used on their next record Unrest. In November 1973, members of the band participated in a live-in-the-studio performance of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells for the BBC,[26] which was later released on the 2004 DVD edition of Oldfield's video compilation, Elements.

During a tour of the Netherlands in December 1973, Geoff Leigh left the group.[16] Looking for more unusual instruments to draw them further away from rock and jazz,[27] Henry Cow asked classically trained Lindsay Cooper (oboe, bassoon) to join. In early 1974 the group began recording Unrest at The Manor. Having only enough prepared material to fill one side of the LP, they developed a studio composition process that produced the second side.[27]

In May 1974, Henry Cow were on tour again around England and Europe with Captain Beefheart. It was during this tour that they realised they were becoming a conventional rock band, playing the same material night after night. Their music was no longer a challenge and they were becoming complacent. After some serious deliberating, they asked Cooper to leave and fulfilled their last outstanding concert obligations (a tour of the Netherlands) as a quartet. Without Cooper they were forced to abandon much of their learned material and worked on a 35–40 minute piece Hodgkinson had written that later became the politically charged "Living in the Heart of the Beast" on their third album, In Praise of Learning.[25]

In November 1974, avant-pop group Slapp Happy (Anthony Moore, Peter Blegvad, Dagmar Krause) invited Henry Cow to record with them on their second album for Virgin. The result was Desperate Straights, an almost entirely Slapp Happy-composed album that surprised critics, considering how dissimilar the two groups were.[28] The success of this venture prompted a merger of the two bands, and in early 1975 they recorded In Praise of Learning at The Manor. The merger ended in April 1975 when Moore and Blegvad left. Krause remained with Henry Cow, which effectively spelled the end of Slapp Happy.[29][30]

Having made guest appearances on both the Henry Cow/Slapp Happy albums, Cooper rejoined in April 1975 and Henry Cow became a sextet. In May 1975 they embarked on a concert tour with Robert Wyatt in England, France and Italy to launch In Praise of Learning and Wyatt's new album, Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard.[31][14] This was followed by a period of almost constant touring across Western Europe that continued until Henry Cow disbanded in 1978.[32][14]

Europe

Henry Cow's music was challenging and uncompromising and this often led to them being accused of deliberately making it unapproachable.[16] In a review of Unrest in New Musical Express on 15 June 1974, Neil Spencer called the band "determinedly inaccessible".[33][a] As a result, Henry Cow were virtually ignored in their own country. Virgin Records too, having started dropping experimental groups in favour of commercial ones, now showed little to no interest in the band. The group continuously considered whether to continue or not; there certainly were no economic inducements. Cutler said, "We had to make what amounted to political decisions about the organization of the group and its relation to the commercial structures, and this was bound to be reflected in the music too."[34] Henry Cow's anti-capitalist stance[35] was brought on partly out of necessity rather than choice. They began working outside the music industry and did everything for themselves. They abandoned agencies and managers and stopped looking for approval from the music press. Henry Cow quickly became self-sufficient and self-reliant.

Virtual exiles from their own country, they made mainland Europe their second home where they (and their music) were well received. After a concert in Rome in July 1975, Henry Cow remained behind with their truck/bus/mobile home and began meeting local musicians, including progressive rock band Stormy Six, and the PCI (Italian Communist Party). The PCI offered them concerts at Festa de L'Unità (large open-air fairs that run every summer all over Italy), and they joined Stormy Six's L'Orchestra, a musicians' co-operative in Milan. Each contact they made led to more contacts and soon doors opened for Henry Cow all over Europe.

Henry Cow performing in Fresnes, France, 16 November 1975. Left to right: Tim Hodgkinson, Lindsay Cooper, Dagmar Krause, John Greaves, Chris Cutler and Fred Frith |

While rehearsing for an upcoming tour of Scandinavia in March 1976, John Greaves left the band to start working on the Kew. Rhone. project with Peter Blegvad, and Dagmar Krause withdrew due to ill health. Committed to the tour, Henry Cow had to perform as a quartet (Hodgkinson, Frith, Cooper and Cutler) and adjust their music accordingly. They took the radical option and abandoned composed material completely in favour of pure improvisation.

In May 1976, Henry Cow compiled a double LP Concerts for a new Norwegian underground label Compendium (re-released later on the budget Virgin sub-label Caroline). For the first time, they did everything themselves: the mastering, cover design, cutting, pressing and manufacturing. The album included an excerpt from one of several concerts performed with guest artist Robert Wyatt in 1975.

Henry Cow began auditioning for a bass player and found Georgie Born, a classically trained cellist and improviser. Even though she had never played bass guitar before,[36] she joined the band in June 1976 and tuned her bass in 5ths like a cello with a lower C.[37] In the interim, the band's compositions, including a new Hodgkinson epic with the working title of "Erk Gah", grew more complex.

Henry Cow returned to London in early 1977, where they merged with the entire Mike Westbrook Brass Band and folk singer Frankie Armstrong to form the Orckestra. They played their first concert at the Moving Left Revue at The Roundhouse in London and then at the Open Air Theatre in Regent's Park. The Orckestra later went on to tour in France, Italy and Scandinavia (extracts from some of these performances were released in 2006 on a CD-single included in the Henry Cow Box). At more or less the same time they set up Music for Socialism and its May Festival. It had been three years since Henry Cow had performed more than one concert a year in their own country. In an attempt to break the apathy that seemed to be discouraging anyone from wanting to put them on, they tried to organise a small alternative tour themselves, but abandoned it after 11 concerts when they started losing money: clearly nothing had changed.

Their contract with Virgin Records had now become a burden to both Henry Cow and Virgin: none of Henry Cow's records were licensed or distributed in the countries in which they spent all their time playing, and Henry Cow were not making any money for Virgin. Henry Cow needed to record again but Virgin refused to give them studio time at The Manor. When Henry Cow referred to the contract ("one month at a first class studio"),[27] Virgin Records (in October 1977) agreed to cancel it.

By now, Krause's health had deteriorated to such an extent that touring became impossible for her and she decided to leave the group, although she agreed to sing on Henry Cow's next album. The recording of this album was to begin at Sunrise studios in Kirchberg, Switzerland in January 1978. However, a group meeting one week before threw into question the material planned for it, the aforementioned "Erk Gah" in particular. Cutler and Frith hurriedly wrote a set of songs which, along with some of the planned material, were duly recorded. On returning to London, another meeting was convened to question the predominance of songs on the album. The group agreed that the songs would be released separately by Cutler and Frith, while the instrumentals would be released later by Henry Cow. This decision, however, spelled the end of the band. Cutler, Frith and Krause released the songs, with four extra tracks recorded at David Vorhaus's Kaleidophon Studio in London, as Hopes and Fears under the name Art Bears, crediting the rest of Henry Cow as guests. Later that year Henry Cow returned to Sunrise, by then without Dagmar Krause and Georgie Born, to record their last album, Western Culture, an instrumental. Annemarie Roelofs had joined the band two months before the split and plays on the album as well.[14]

Rock in Opposition

Henry Cow agreed to disband as a permanent group, but did not announce the fact immediately. They continued for another six months, creating a new set of material (recorded later to complete Western Culture) and revisited for the last time all the places that had supported them over the years.

In March 1978, Henry Cow invited four European groups, Stormy Six (Italy), Samla Mammas Manna (Sweden), Univers Zero (Belgium) and Etron Fou Leloublan (France), to come to London and perform in a festival Henry Cow had organised called Rock in Opposition, or RIO. Throughout Europe, Henry Cow had encountered many "progressive" groups refusing to bow to the hegemony of American and British rock music. Instead they drew on non-American music sources, such as local folk music and 20th century "classical" or "art music", and often sang in their own languages. As was the case with Henry Cow, these groups struggled to survive: record companies were not interested in their music. Although these groups and Henry Cow were musically diverse, what they had in common was: (1) their independence and opposition to the established Rock business; and (2) a determination to pursue their own work regardless.

After the festival, RIO was formalised as an organisation with a charter whose aim was to represent and promote its members. RIO thus became a collective of bands united in their opposition to the music industry and the pressures to compromise their music.

Henry Cow's last concert was held in Milan on 25 July 1978. A final performance scheduled at the Annual World Youth Festival in Cuba never materialised.[17] In August they returned to the Sunrise studios to complete Western Culture, after which the band officially announced their break-up in the press, stating that "… although the group as a commodity, as a name, ceases to exist the work of the group will go on …"[9]

Western Culture was released on Henry Cow's own Broadcast label. Shortly afterward, Chris Cutler launched Recommended Records, his own independent label and non-commercial record distribution network.

Legacy

The legacy of Henry Cow continues. Former members have collaborated in numerous projects, including:

- Art Bears

- Fred Frith, Chris Cutler and Dagmar Krause (1978–1981)

- Rags (Lindsay Cooper solo album)

- Lindsay Cooper, Fred Frith, Chris Cutler, Georgie Born and others (1979–1980)

- The Last Nightingale (benefit album for the striking miners in the 1984–1985 UK miners' strike)

- Lindsay Cooper, Chris Cutler, Tim Hodgkinson and others (1984)

- News from Babel

- Chris Cutler, Lindsay Cooper, Georgie Born, Dagmar Krause, Robert Wyatt and others (1983–1986)

- Duck and Cover (commission from the Berlin Jazz Festival)

- Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, Dagmar Krause and others (1983–1984)

- Each in Our Own Thoughts (Tim Hodgkinson solo album)

- Tim Hodgkinson, Chris Cutler, Lindsay Cooper, Dagmar Krause and others (1993) – the track "Hold to the Zero Burn, Imagine" was a Henry Cow piece performed by the group between 1976 and 1978 (as "Erk Gah") but never recorded in the studio

- Live improvisations

- Fred Frith and Chris Cutler (1979–2010)

- Fred Frith and Tim Hodgkinson (1988–1990)

- Chris Cutler, Fred Frith and Tim Hodgkinson (1986 and 2006)

- Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, John Greaves and Tim Hodgkinson (2022–2023, as Henry Now)

- Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, Tim Hodgkinson and Annemarie Roelofs (2024, as Henry Now)

- The Artaud Beats

- Chris Cutler, John Greaves, Geoff Leigh and others (2009–present)

- The Watts

- Chris Cutler, Tim Hodgkinson and others (2018)

- Projects around Lindsay Cooper's music

- Henry Cow and others play the music of Lindsay Cooper: Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, John Greaves, Tim Hodgkinson, Dagmar Krause, Annemarie Roelofs and others (2014)

- Half the Sky: Chris Cutler, Dagmar Krause and others (2017)

- Lindsay Cooper Songbook (a continuation of Half the Sky): Chris Cutler, Dagmar Krause, Tim Hodgkinson, John Greaves and others (2018)

A partial Henry Cow reunion occurred in 1993 when Hodgkinson, Cutler, Cooper and Krause came together to record "Hold to the Zero Burn, Imagine" for Hodgkinson's solo album, Each in Our Own Thoughts. The song was formerly known as "Erk Gah" and composed by Hodgkinson for, and performed by, Henry Cow. When asked in 1998 about a possible Henry Cow reunion concert, Frith replied, "Forget it! We're all much too busy."[38] In December 2006, Cutler, Frith and Hodgkinson performed together at The Stone in New York City, only their second concert performance since Henry Cow broke up in 1978.[39][40] The first was in London in 1986. Frith and Hodgkinson also performed improvised duo concerts in 1990. Extracts of the concerts were released in 1992 as Live Improvisations.

Cooper died in September 2013;[41][42] In June 2014, it was announced that there would be a Henry Cow reunion as part of two concerts celebrating her life and works. The band, including Henry Cow members Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, John Greaves, Tim Hodgkinson, Annemarie Roelofs and Dagmar Krause, performed a set of Cooper's compositions in Henry Cow, then in News from Babel, Music for Films and Oh Moscow. The Henry Cow set featured Cutler, Frith, Greaves, Hodgkinson, Roelofs, Michel Berckmans, Alfred Harth and, on one piece, Veryan Weston and Zeena Parkins; Krause performed later in the evening, but not on the Henry Cow set. The concerts were performed at the Barbican Centre, London on 21 November 2014, as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival, and at the Lawrence Batley Theatre, Huddersfield as part of the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, on 22 November 2014.[43][44] A third remembrance concert for Cooper featuring the same line-up above was held in Forlì, Italy on 23 November 2014.[45]

In a review of the Barbican concert on 21 November, Dom Lawson of The Guardian called it "a fitting salute to Cooper's life", adding "what tonight’s experience never becomes is self‑indulgent: there’s a sharpness to the intricate arrangements as very obvious waves of passion and commitment from everyone on stage flow and spread across the auditorium."[46]

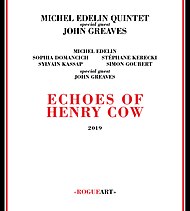

In May 2019, the Michel Edelin Quintet with John Greaves released Echoes of Henry Cow, an album of variations on Henry Cow compositions and other music.[47] Aymeric Leroy wrote in the liner notes that it should not be seen as a Henry Cow tribute album, but rather "echoes (much transformed during its long journey through time, space, memory and the mysterious twists and turns of the creative process) in [Edelin's] own musical inner world".[47]

In September 2019, American historian of experimental music and an associate professor of music at Cornell University, Benjamin Piekut published Henry Cow: The World Is a Problem, a detailed biography and analysis of the band from their inception in 1968 to their demise in 1978.[48] On 18 November 2022, Greaves, Frith, Hodgkinson and Cutler reunited for concerts in Piacenza, Italy, under the moniker of Henry Now with Italian friend Annie Barbazza guesting.[49] The same line-up played two gigs in the Czech Republic in November 2023.[50][51] In January 2024 Henry Now performed in Barcelona with a line-up of Cutler, Frith, Hodgkinson and Annemarie Roelofs.[52][53][better source needed]

Music

Henry Cow's music included elaborately scored pieces (often with complex time signatures), tape loops and manipulations, "flat-out free improvisation" and songs.[54] It incorporated elements of jazz, rock, contemporary classical music and the avant-garde. Dagmar Krause's vocals added another dimension to their sound, giving it a dramatic, almost Brechtian flair. Music journalists at the time often underestimated the formal compositional element of their music,[17] while others simply dismissed it as being "inaccessible".[16]

John Kelman wrote at All About Jazz that "Henry Cow represented a new kind of classical chamber music; one where spontaneity was a partial component, and the instrumentation used created textures that defied those looking for tradition and convention."[54] Edward Macan in his 1997 book Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture described Henry Cow's music as "highly eclectic" and said that their pieces often included "furious atonal instrumental passages with no discernable melodic contour or key center, impossibly complex shifting meters alternating with freely ametric sections with no definable beat or regular recurring rhythms, and jagged, sprechstimme-like vocal lines that blur the line between song and speech."[34]

Trond Einar Garmo described Henry Cow's music as avant-garde rock.[55] Writing in his book, Henry Cow: An Analysis of Avant Garde Rock (2020), Garmo stated:

I have chosen to use the term 'avant-garde rock' for Henry Cow's music. The word 'avant-garde' is usually associated with art that is 'difficult', 'incomprehensible', and to some extent 'meaningless'. The actual meaning of the word, however, is 'vanguard'. Avant-garde artists are, therefore, artists who find new directions and expand the boundaries of the art form in which they operate. And it is in this sense that I have used the word. Avant-garde rock represents the most experimental and radical trends within rock.[55]

Henry Cow's music was challenging, not only to the listener, but also to the band themselves. They often composed pieces to challenge their own capabilities. Some of their music was scored beyond the conventional ranges of their instruments, necessitating that they "reinvent their instruments" and learn how to play them in completely new ways.[17][18] Frith explained in a 1973 interview, "What we've done is to literally teach ourselves to ... compos[e] music which we could not initially, play. Because of that attitude, we can go on forever. It's a self-generative concept which gives us a sense of purpose most groups simply don't have."[56] And yet their music may not have been as good as it could have been. Henry Cow conducted their affairs as a collective and all decisions, including those related to their music, had to be approved by the group. Cutler said at a conference on "Composition and Experimentation in British Rock 1967–1976" in Italy in 2005 that Henry Cow had a rule that "the composer no longer owned the composition once the band had started to work on it."[57] In a 1998 interview Frith said that this may have led to much of Henry Cow's material being "watered down" rather than strengthened.[38] He felt that "this ... was a big mistake, and a lot of our best ideas may not have been fully realised as a result of it."[38] Cutler wrote that when Art Bears was formed in 1978, he and Frith decided there would be "no discussions; if someone had an idea, they put it to tape. Then we'd listen and it would be immediately clear if it worked, didn't work or could work if pursued."[58]

Henry Cow were largely a live band, yet of the original six albums they made, only one, Concerts gave a glimpse of their live performances. In January 2009 Recommended Records released The 40th Anniversary Henry Cow Box Set, a nine-CD plus one-DVD collection of over 10 hours of previously unreleased and mostly live recordings made between 1972 and 1978, over four hours of which was improvised. This offered, "for the first time," according to Kelman, "a comprehensive account of Henry Cow's breadth and depth."[54]

Members

Source: The Canterbury Website Henry Cow Chronology.[14]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fred Frith | 1968–1978 |

|

all releases | |

| Tim Hodgkinson |

| |||

| David Attwooll | 1968 (died 2016) | drums | none[b] | |

| Rob Brooks | 1968 | rhythm guitar | ||

| Joss Grahame | bass guitar | |||

| Andy Spooner | harmonica | |||

| Andy Powell | 1968–1969 |

| ||

| John Greaves | 1969–1976 |

|

| |

| Sean Jenkins | 1969–1971 | drums | none[b][c] | |

| Martin Ditcham | 1971 | The Henry Cow Box Redux: The Complete Henry Cow (2019)[c] | ||

| Chris Cutler | 1971–1978 |

|

all releases | |

| Geoff Leigh | 1972–1973 (session afterward) |

|

| |

| Lindsay Cooper | 1974–1978 (died 2013) |

|

| |

| Peter Blegvad | 1974–1975[d] |

|

| |

| Anthony Moore |

| |||

| Dagmar Krause | 1974–1977[d] |

|

| |

| Georgie Born | 1976–1978 |

|

| |

| Annemarie Roelofs | 1978 |

|

|

Timeline

Notes: before Sean Jenkins joined, the band auditioned several other drummers. According to Fred Frith, between 1969 and 1971, the band played more as a trio than with a drummer.[14] From November 1974 to April 1975, Henry Cow merged with Slapp Happy to form one group. The band's final studio album, Western Culture, was released in 1979 after the group had split up.

Discography

Studio albums

| Year | Title | Format | Label | Released | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Legend [e] | LP | Virgin (UK) | September 1973 | |

| 1974 | Unrest | LP | Virgin (UK) | May 1974 | |

| 1975 | Desperate Straights | LP | Virgin (UK) | March 1975 | Collaborative album with Slapp Happy. |

| In Praise of Learning | LP | Virgin (UK) | May 1975 | Collaborative album with Slapp Happy. | |

| 1979 | Western Culture | LP | Broadcast (UK) | 1979 |

See also

Notes

- ^ Cutler responded to Spencer's claim by writing a letter to the editor of New Musical Express (published 29 June 1974) in which he said Spencer was "imputing to us a complicity in precisely that attitude of irresponsible cynicism that we exist to destroy", and that he was projecting his own cynicism onto them, which "help[s] to actually create that very antisocial effect you are pretending to criticise in us."[33]

- ^ a b Did not appear on any officially released Henry Cow recordings.

- ^ a b According to The Henry Cow Box Redux: The Complete Henry Cow liner notes, Martin Ditcham plays on one track on Ex Box – Collected Fragments 1971–1978,[59] but several sources have stated that this is incorrect, and that it was Henry Cow's previous drummer, Sean Jenkins.[60][16][14]

- ^ a b Blegvad, Moore and Krause were members of Slapp Happy. From November 1974 to April 1975 Slapp Happy and Henry Cow were merged as one group. When the two groups separated, Krause decided to continue with Henry Cow.

- ^ Legend is also known as The Henry Cow Legend and Leg End.

References

- ^ Jazz Forum (51–56 ed.). For Jazz, sp. z o. o. 1978. p. 7.

- ^ Marsh, Peter. "Henry Cow/Slapp Happy Desperate Straights Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ Robbins, Ira (1987). The New Music Record Guide. Omnibus Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7119-1115-4.

- ^ a b Boisen, Myles. "Henry Cow | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Smith, Sid (17 April 2015). "The Canterbury Scene: The Sound Of The Underground". Prog. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ The Beat. Vol. 14. Bongo Productions. 1995. p. 20.

- ^ Kenny, Glenn. "Henry Cow". Trouser Press. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John, eds. (1983). The New Rolling Stone Record Guide (2nd ed.). Random House/Rolling Stone Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-394-72107-1.

- ^ a b "Henry Cow". The Canterbury Music Website. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ Cutler 2009a, p. 21.

- ^ Brook, Chris (2003). "Henry Cow". In Buckley, Peter (ed.). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. p. 490. ISBN 1-84353-105-4.

- ^ Cutler 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Murray, Charles Shaar (31 August 1974). "Henry Cow: Gerroff An' Milk It". New Musical Express. Retrieved 13 June 2018 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Henry Cow Chronology". Calyx: The Canterbury Music Website. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Obituary: David Attwooll". University of Liverpool. 11 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Ansell, Kenneth (April 1975). "Dissecting the Cow". ZigZag. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wright, Patrick (11 November 1995). "Resist Me, Make Me Strong: On Chris Cutler" (PDF). The Guardian. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ a b Lake, Steve (16 April 1977). "Cow: moving left ...". Melody Maker. p. 38.

- ^ a b Romano 2014, "Chapter 17 | Shock to the System | Henry Cow and Rock in Opposition".

- ^ Romano 2014, "Chapter 8 | Escape Artists – Designing and Creating Prog Rock's Wondrous Visuals | Henry Cow: Legend (1973)".

- ^ Cutler 2009a, p. 15.

- ^ Piekut 2019, p. 73.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (14 October 1972). "Ayers / Cabaret Voltaire". New Musical Express.

- ^ Piekut 2019, pp. 75, 98.

- ^ a b Martens, Matthew (October 1996). "Henry Cow". Perfect Sound Forever. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Mike Oldfield (with Mick Taylor, Steve Hillage and members of Henry Cow, Gong and Soft Machine) – Tubular Bells (Live BBC Video 1973)". MOG. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Cutler, Chris. "Henry Cow". Chris Cutler. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Mills, Ted. "Desperate Straights". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Slapp Happy". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Piekut 2019, p. 196.

- ^ Piekut 2019, p. 212.

- ^ Gross, Jason (March 1997). "Chris Cutler". Perfect Sound Forever. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b Piekut 2019, p. 141.

- ^ a b Macan, Edward (1997). Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture. Oxford University Press. p. 1973. ISBN 0-19-509888-9.

- ^ Glanden, Brad (18 November 2006). "Henry Cow: Concerts". All About Jazz. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Cutler 2009b, p. 34.

- ^ Cutler 2009b, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Warburton, Dan (19 March 1998). "Fred Frith interview". Paris Transatlantic Magazine. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ "The Stone calendar". The Stone, New York City. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ "Fred Frith – Tim Hodgkinson – Chris Cutler, The Stone NYC, December 16, 2006". Punkcast. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ Fordham, John (24 September 2013). "Lindsay Cooper obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Mack, Shane (19 September 2013). "RIP: Lindsay Cooper, member of Comus and Henry Cow collaborator". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Legendary bands celebrate the life and work of Lindsay Cooper". hcmf// (Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival). 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ "HENRY COW, MUSIC FOR FILMS, NEWS FROM BABEL and OH MOSCOW play the music of Lindsay Cooper". Serious. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ "HENRY COW | MUSIC FOR FILM | NEWS FROM BABEL | OH MOSCOW". Area Sismica. 14 August 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Lawson, Dom (2 January 2015). "HENRY COW LIVE". teamrock.com. Retrieved 8 January 2015.(registration required)

- ^ a b "Michel Edelin Quintet with special guest John Greaves: Echoes of Henry Cow". RogueArt. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "Henry Cow: The World Is a Problem Book Release". New York University College of Arts & Science. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "Henry Now in Piacenza" (in Italian). 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Henry Now – Fred Frith, Chros Cutler, Tim Hodgkinson, John Greaves | jazzinec.cz". www.jazzinec.cz.

- ^ o, ArtFrame Palác Akropolis s r. "ÚTERÝ 07. 11 HENRY NOW /UK / 19:30, VELKÝ SÁL". Palác Akropolis.

- ^ "Henry Now – L'Auditori". www.auditori.cat.

- ^ "Instagram".

- ^ a b c Kelman, John (12 January 2009). "Henry Cow: The 40th Anniversary Henry Cow Box Set". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ a b Garmo 2020, p. 3.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (7 April 1973). "Henry Cow: Just Happy Playing Their Music". New Musical Express. Retrieved 18 June 2018 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Cutler, Chris (21 October 2005). "Conference on Composition and Experimentation in British Rock 1967–1976, Palazzo Cittanova, Italy". Department of Musicology and Cultural Heritage, University of Pavia. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Cutler, Chris. "Art Bears". Chris Cutler. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Cutler, Chris (2019). Ex Box – Collected Fragments 1971–1978 (CD liner notes). Henry Cow. London: Recommended Records.

- ^ Piekut 2019, p. 49.

Works cited

- Cutler, Chris (2006). Concerts (CD booklet). Henry Cow. London: Recommended Records.

- Cutler, Chris, ed. (2009a). "The Road: Volumes 1–5". The 40th Anniversary Henry Cow Box Set (box set booklet). Henry Cow. London: Recommended Records.

- Cutler, Chris, ed. (2009b). "The Road: Volumes 6–10". The 40th Anniversary Henry Cow Box Set (box set booklet). Henry Cow. London: Recommended Records.

- Garmo, Trond Einar (2020). Henry Cow: An Analysis of Avant Garde Rock. London: ReR Megacorp / November Books. ISBN 978-0-95601-84-4-1.

- Piekut, Benjamin (2019). Henry Cow: The World Is a Problem. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-47800-405-9.

- Romano, Will (2014). Prog Rock FAQ: All That's Left To Know About Rock's Most Progressive Music (e-book ed.). Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-587-3.

Further reading

- Cutler, Chris; Hodgkinson, Tim (1981). The Henry Cow Book. London: Third Step Printworks. ISBN 0-9508870-0-5.

- Cutler, Chris (1985). File Under Popular: Theoretical and Critical Writings on Music. London: November Books. ISBN 0-946423-01-6.

External links

- Unofficial Henry Cow Site at the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

- Perfect Sound Forever. Henry Cow biography.

- Calyx: The Canterbury Website. Henry Cow lyrics.

- Collapso–Canterbury Music Family Tree. Henry Cow family tree.

- Perfect Sound Forever. Interview with Chris Cutler (March 1997).

- BBC Radio 1. Henry Cow John Peel sessions.

- "Henry Cow: The greatest band you never heard of". The Boston Phoenix (3 June 1980).