HMS St Fiorenzo (1794)

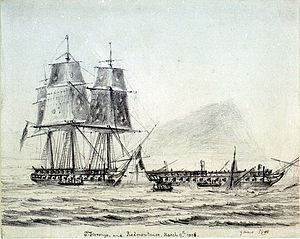

HMS St Fiorenzo and Piémontaise on 9 March 1808 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Minerve |

| Builder | Toulon |

| Laid down | January 1782 |

| Launched | 31 July 1782 |

| Completed | By October 1782 |

| Captured |

|

| Name | HMS St Fiorenzo |

| Acquired | 19 February 1794 |

| Honours and awards |

|

| Fate | Broken up in September 1837 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | 38-gun fifth rate |

| Tons burthen | 1,03186⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 39 ft 6 in (12.0 m) |

| Depth of hold | 13 ft 3 in (4.0 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 274 (British service) |

| Armament |

|

Minerve was a 40-gun frigate of the French Navy, lead ship of her class. She operated in the Mediterranean during the French Revolutionary Wars. Her crew scuttled her at Saint-Florent to avoid capture when the British invaded Corsica in 1794, but the British managed to raise her and recommissioned her in the Royal Navy as the 38-gun fifth rate HMS St Fiorenzo (also San Fiorenzo).

She went on to serve under a number of the most distinguished naval commanders of her age, in theatres ranging from the English Channel to the East Indies. During this time she was active against enemy privateers, and on several occasions she engaged ships larger than herself, being rewarded with victory on each occasion. She captured the 40-gun Résistance and the 22-gun Constance in 1797, the 36-gun Psyché in 1805, and the 40-gun Piémontaise in 1808. (These actions would earn the crew members involved clasps to the Naval General Service Medal.) After she became too old for frigate duties, the Admiralty had her converted for successively less active roles. She initially became a troopship and then a receiving ship. Finally she was broken up in 1837 after a long period as a lazarette.

French career

The French built Minerve at Toulon, laying her down on 10 February 1782 and launching her on 21 July 1782. She was the lead ship of her class.[4]

Minerve began her career in the Mediterranean, in particular operating in the Levant campaign from 1790 to 1791. In March 1793 she and Melpomène escorted from Toulon to Algiers two xebecs that the French had outfitted for the Dey. On Minerve's return to Toulon her commander was arrested following an insurrection on board. On 18 February 1794, her commander scuttled her before the British under Sir David Dundas captured the town of San Fiorenzo (San Fiurenzu or Saint-Florent, Haute-Corse) in the Gulf of St. Florent in Corsica. (Other accounts suggest that gunfire from British shore batteries sank her.) The British found Minerve on 19 February 1794, and were able to refloat her.[5] They then took her into service as a 38-gun frigate under the name St Fiorenzo.[6]

British career

Service in the Channel

She was initially under the command of Captain Charles Tyler, but passed under Captain Sir Charles Hamilton in July 1794.[4] Hamilton sailed her back to Chatham, where she arrived on 22 November and was registered as a Royal Navy ship on 30 May 1795.[4] She was then commissioned in June that year under Captain Sir Harry Neale. Neale was to command her for the next five years.[4]

St Fiorenzo was among the 25 British warships in the fleet under the command of Admiral John Colpoys that shared in the capture on 2 November 1796 of the French privateer Franklyn.[7] Twenty-six days later, St Fiorenzo was in company with Phaeton when they captured the French brig Anne. At some point, St Fiorenzo also captured the brig Cynthia.[8]

Capture of Résistance and Constance

On 9 March 1797 St Fiorenzo was sailing in company with Captain John Cooke's Nymphe, when they sighted two sails heading for Brest.[9] These turned out to be the French frigate Résistance and the corvette Constance, returning from the short-lived, quixotic and unsuccessful French raid on Fishguard in Wales, where they had landed troops.[9][10] Cooke and Neale chased after them, and engaged them for half an hour, after which both French ships surrendered.[10]

There were no casualties or damage on either of the British ships. Resistance had ten men killed and nine wounded; Constance had eight men killed and six wounded.[10]

Resistance had 48 guns, with 18-pounders on her main deck, and a crew of 345 men. Constance had twenty-four 9-pounder guns, and a crew of 181 men.[10] The Royal Navy took both into service. Résistance became HMS Fisgard, while Constance retained her name.[9] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General service Medal with clasp "San Fiorenzo 8 March 1797" to surviving claimants from the action.[a]

Channel

St Fiorenzo was one of the ships caught up in the mutiny at the Nore, but was one of the few ships to remain loyal to her commander. She subsequently escaped to Harwich after enduring musket and grapeshot fire from the mutinous ships that left four of the crew wounded.[4][11]

Further successes followed later that year. She captured the French privateer lugger Unité off The Owers on 3 June 1797. Unité was armed with 14 guns and had a crew of 58 men commanded by Citizen Charles Roberts. She was three days out of Morlaix without having captured anything.[12]

Then on 1 July St Fiorenzo captured the French privateer lugger Castor off the Scilly Isles. Castor too had been armed with 14 guns, all of which she had thrown overboard during the chase in an attempt to lighten herself and so gain speed, and had a crew of 57 men. She was 18 days out of Saint Malo and in that time had captured the brig Resolution, which had been carrying a cargo of salt.[13]

St Fiorenzo and Clyde shared in the capture in November and December 1797 of the French brigs Minerva and Succès.[14] In addition to the capture of the privateer Succès on 14 December, St Fiorenzo and Clyde captured the privateer Dorade two days later.[15] The actual captor of Dorade was Clyde. Dorade was from Bordeaux and was pierced for 18 guns, though she only had 12. She had been out 50 days and had been cruising off the Azores and Madeira, but had captured nothing. She and her crew of 93 men were on their way home when Clyde captured her. Unfortunately, the commander of the prize crew hoisted too much sail with the result that Dorade overturned, drowning all 19 members of the prize crew.[16]

St Fiorenzo, Cormorant and Cynthia shared in the recapture of the American brig Betty on 16 February 1798.[17][18] On 9 March St Fiorenzo recaptured the brig Cynthia.[19] Almost a month later, on 7 April, St Fiorenzo, in company with Impetueux, recaptured the Ulysses.[20] Ulysses, Smith, master, had been on her way from Santo Domingo to London when the French privateer Grande Buonaparte, of 22 guns and 200 men, captured her on 2 April. St Fiorenzo sent Ulysses into Plymouth.[21]

On 23 May St Fiorenzo captured the pram (chasse maree) Maria. two days later, St Fiorenzo and Impetueux captured the ship Fair American.[22] On 1 June, she added the brig Zeniphe to her list of captures, and then six days later, two empty sloops.[23] Sans Pareil, St Fiorenzo, and Amelia shared in the capture of the French sloop Marie Catharine.[24] St Fiorenzo, Phaeton, Anson and Stagg shared in the proceeds of the capture on 23 June of Jonge Marius.[25] That same day Phaeton captured the Speculation; San Fiorenzo's officers entitled to first or second-class shares in prize money shared by agreement.[26]

On 29 June Pique, Jason and Mermaid chased a French frigate. Pique and Jason chased her down and captured her in the Breton Passage on 30 June 1798, after an engagement in which the French suffered some 170 men killed. The French vessel was Seine, which the Royal Navy took into service under her existing name. In the fight Jason, Pique and Seine ran aground. Mermaid arrived and retrieved Jason, but Pique had to be destroyed. St Fiorenzo too arrived and was instrumental in recovering Seine.[27]

On 9 November, St Fiorenzo captured the French privateer Resource.[19] Head money for the men on the privateer and salvage for Cynthia in March was paid in February 1810.[b]

On 11 and 12 December 1798 St Fiorenzo and Triton captured and sent into Plymouth the Spanish privateer St Joseph y Animas and the French privateer Rusée, and recaptured the brig George, of London, which had originally been sailing from Bristol to Lisbon, loaded with a cargo of coals, copper, and bottles. St Joseph y Animas was armed with four brass 6-pounder guns and had a crew of 64 men. Rusée was coppered and just off the stocks, she carried fourteen 4-pounder guns and a crew of 60. Neale recommended that the Navy take her into service.[29] On 15 December St Fiorenzo captured the Spanish brig Nostra Senora Del Carmen y Animas.[30]

In late 1798 or early 1799, San Fiorenzo, Phaeton, Anson, Clyde, Mermaid, and Stag, shared in the capture of the chasse maree Marie Perotte and a sloop of unknown name, as well as the recapture of Sea Nymphe and Mary.[31] On 9 March 1799, St Fiorenzo and Clyde captured the French sloop St Joseph.[32] Three days later Triton, St Fiorenzo, Naiad and Cambrian captured the French merchant ship Victoire.[33]

On 9 April 1799, after reconnoitering two French frigates in L'Orient, St Fiorenzo and HMS Amelia sailed towards Belle Île. Conditions were hazy and although Neale had sighted some vessels, it was only when he had passed the island that he discovered three French frigates and a large gun vessel. At that instant a sudden squall carried away Amelia's main-top-mast and fore and mizzen top-gallant masts; the fall of the main-top-mast tore away much of the mainsail from the yard. Neale shortened St Fiorenzo's sail and ordered Amelia to keep close to St Fiorenzo to maintain the weather gage, and to prepare for battle. An action commenced but the French vessels avoided close-quarter action and, although the British ships came under fire from shore batteries, they had to bear down on the French three times to engage them. After nearly two hours the French wore ship and sailed away to take refuge in the Loire, with the gun-vessel returning to Belle Île.[34]

Amelia lost two killed and 17 wounded in the engagement. St Fiorenzo lost one man killed and eighteen wounded.[34]

That evening St Fiorenzo captured a French brig and learned that the French frigates were Vengeance, Sémillante and Cornélie.[34] The British further learned that Cornélie had lost some 100 men dead and wounded, with one of the wounded being her commodore. Later reports mentioned that Captain Caro of Vengeance had been mortally wounded and that Sémillante had 15 dead.[35]

Then on 13 April, St Fiorenzo captured the French ship Entreprenant.[36] On 17 April St Fiorenzo returned to Plymouth, bringing with her a French brig that she had captured. The French vessel had been sailing from San Domingo to Lorient with a cargo of sugar and coffee. St Fiorenzo had also captured another French brig, sailing in ballast, but she had not yet arrived.[34] That same month St Fiorenzo captured the Prussian brig Vrou Helena Catherina.[19] On 2 July 1799 St Fiorenzo took part in an attack on a Spanish squadron anchored in the Aix Roads.[4]

On 13 November 1800 St Fiorenzo and Cambrian recaptured the merchantman Hebe, which the 18-gun French privateer Grande Decide had captured about a week earlier.[37]

Captain Charles Paterson took over command in January 1801, serving in the Mediterranean. St Fiorenzo, Loire, Wolverine, Aggressor, Seahorse, Censor and hired armed cutter Swift shared in the capture on 11 and 12 August 1801 of the Prussian brigs Vennerne and Elizabeth.[38] On 30 September 1801 St Fiorenzo captured the schooner Worcester.[39]

In May 1802 Captain Joseph Bingham succeeded Paterson. He would serve as St Fiorenzo's commander until 1804.[4]

East Indies

Bingham sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, and spent the next couple of years operating in the Indian Ocean. On 14 January 1804 St Fiorenzo gave chase to the French naval chasse-marée and aviso Passe-Partout off Mount Dilly on the Malabar Coast.[40] When the wind began to fail, Bingham sent three of his boats after the quarry. Once alongside, in two minutes the British had captured the French vessel, despite fire from two brass six-pounder guns, six brass swivel guns and small arms. Out of her 25-man crew, Passe-Portout had two dead and five seriously wounded, including the captain, who was mortally wounded; the British suffered only one man slightly wounded.[41] Bingham discovered that the French had outfitted Passe Partout to land three officers on the coast to incite the Mahratta states to attack the British. Bingham passed on the intelligence with the result that the British at Poona were able to capture the Frenchmen.[42]

Bingham's successor was Captain Walter Bathurst, who commanded St Fiorenzo in 1805. Captain Henry Lambert (acting), replaced Bathurst.[40]

Psyché

On 13 February 1805 St Fiorenzo found the French frigate Psyché and two vessels that looked like merchantmen, off Vishakhapatnam. On the evening of the 14th, St Fiorenzo recaptured one of the merchantmen, Thetis, which was a prize to Psyché and which the French had abandoned. He put a prize crew aboard her and then engaged the other two vessels. After a fierce battle of more than three hours, Captain Bergeret, the French commander of Psyché, sent a boat to announce that she had struck her colours. She had lost 57 men killed and 70 men wounded; St Fiorenzo had 12 killed and 56 wounded.[43] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "San Fiorenzo 14 Feby. 1805" to any surviving claimants from the action.

During the engagement the third vessel, Equivoque, occasionally intervened, firing at St Fiorenzo. She was a privateer of ten guns and a crew of forty men under the command of a lieutenant. She was the former local ship Pidgeon, which Bergeret had captured and fitted out as a privateer. She escaped.[43]

Lambert was promoted to another command. Captain Patrick Campbell then commanded St Fiorenzo between 1806 and 1807.[40]

Capture of Piémontaise

St Fiorenzo's next commander was Captain George Nicholas Hardinge, who on 6 March 1808 encountered the 50-gun French frigate Piémontaise, which had been raiding British shipping off the Indian coast. Piémontaise was under the command of Captain Jacques Epron and had sailed from Île de France on 30 December with a crew of 366 Frenchmen, together with almost 200 lascars to work the sails.[44]

Hardinge was patrolling when, after having passed three East Indiamen, he spotted a frigate that would not identify itself. St Fiorenzo sailed towards the Frenchman, who attempted to escape.[44] St Fiorenzo chased Piémontaise for the next several days, with intermittent fighting as the French turned to engage their pursuer, before sailing away again. On 7 March the British lost eight men killed and suffered many wounded, two of whom died later.

St Fiorenzo finally brought Piémontaise to a decisive battle late on 8 March in the Gulf of Mannar, where after an hour and twenty minutes of fierce fighting, the French surrendered. French losses amounted to 48 dead and 112 wounded, while over the three days the British lost 13 dead and 25 wounded.[44][c] Captain Hardinge was among the dead, killed by grapeshot from the second broadside in the last engagement.[44] Lieutenant William Dawson took command and brought both vessels back to Colombo, even though Piémontaise's three masts fell over her side early in the morning of the 9th.[44]

Piémontaise also had on board British army officers and captains and officers from prizes that she had taken. These men helped organize the lascars to jury-rig masts and bring Piémontaise into port. St Fiorenzo had too few men and too many casualties and prisoners to guard to provide much assistance.

Aftermath

On 29 November 1809, His Majesty George III granted to the Hardinge family an augmentation to their coat of arms commemorating both the victory over Piémontaise and Hardinge's earlier victory over Atalante.[46] The merchants, shipowners, and underwriters of Bombay voted the sum of £500 to be "distributed to the Sufferers in the Action on the 8th March 1808". Sixteen men died without receiving their portion and the grantors paid for a notice in the London Gazette calling on the relatives of the men to claim their shares.[47] By September 1818, no one had come forward for the money due for eight seamen and marines; the Treasury agreed to hold £160 in trust (£20 per man) should any relative come forward later.[48] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "San Fiorenzo 8 March 1808" to any surviving claimants from the action.

Hardinge's successor was Captain John Bastard, who commanded St Fiorenzo until she was paid off later in 1808.[40]

Later career and fate

St Fiorenzo was then fitted out at Woolwich for service in the Baltic, under the command of Henry Matson.[40] She took part in the Walcheren Campaign in 1809. Her crew therefore qualified for the prize money from the expedition.[49]

St Fiorenzo was then refitted as a 22-gun troopship and sent to Lisbon under Commander Edmund Knox.[40] She was further fitted in 1812, this time to serve as a receiving ship at Woolwich, before being laid up in ordinary at Chatham. Her final service was as a lazarette at Sheerness, where she remained between 1818 and 1837. She was broken up at Deptford in September 1837, after 43 years with the Royal Navy.[40]

Notes

- ^ The reason for the discrepancy between the date of the action and the date on the clasp was that the Admiralty considered that a day ran from noon to noon. Thus the morning of 9 March was, to the Admiralty, the end of 8 March.

- ^ A petty officer received £1 8s 3d; an able seaman received 6s 10d.[28]

- ^ The initial report gave the casualties as 13 killed and 24 wounded for the British, and 50 killed and 100 wounded for the French.[45]

Citations

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 238.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 240.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f g Winfield (2008), p. 148.

- ^ Collingwood, Harry, Under the Meteor Flag: Log of a Midshipman During the French Revolutionary War, 1884, p.181

- ^ Colledge. Ships of the Royal Navy. p. 305.

- ^ "No. 14057". The London Gazette. 17 October 1797. p. 1000.

- ^ "No. 14008". The London Gazette. 9 May 1797. p. 423.

- ^ a b c James. James' Naval History. pp. 95–6.

- ^ a b c d "No. 13992". The London Gazette. 14 March 1797. pp. 251–252.

- ^ Guttridge. Mutiny. p. 67.

- ^ "No. 14015". The London Gazette. 3 June 1797. p. 514.

- ^ "No. 14026". The London Gazette. 8 July 1797. p. 645.

- ^ "No. 15045". The London Gazette. 28 July 1798. p. 714.

- ^ "No. 15080". The London Gazette. 13 November 1798. p. 1091.

- ^ "No. 14076". The London Gazette. 23 December 1797. p. 1221.

- ^ "No. 15018". The London Gazette. 22 May 1798. p. 436.

- ^ "No. 15024". The London Gazette. 2 June 1798. p. 486.

- ^ a b c "No. 16292". The London Gazette. 26 August 1809. p. 1372.

- ^ "No. 15046". The London Gazette. 31 July 1798. p. 728.

- ^ Lloyd's List, no. 2993,[1] – accessed 5 February 2014.

- ^ "No. 15296". The London Gazette. 23 September 1800. p. 1111.

- ^ "No. 15136". The London Gazette. 21 May 1799. p. 496.

- ^ "No. 15049". The London Gazette. 11 August 1798. p. 761.

- ^ "No. 15198". The London Gazette. 26 October 1799. p. 1108.

- ^ "No. 15762". The London Gazette. 11 December 1804. p. 1504.

- ^ "No. 15040". The London Gazette. 10 July 1798. pp. 650–651.

- ^ "No. 16340". The London Gazette. 6 February 1810. p. 200.

- ^ "No. 15093". The London Gazette. 29 December 1798. p. 1249.

- ^ "No. 15235". The London Gazette. 1 March 1800. p. 218.

- ^ "No. 15118". The London Gazette. 23 March 1799. p. 279.

- ^ "No. 15185". The London Gazette. 21 September 1799. p. 969.

- ^ "No. 15338". The London Gazette. 17 February 1801. p. 208.

- ^ a b c d "No. 15126". The London Gazette. 20 April 1799. p. 371.

- ^ James (1837), Vol. 2, pp.334–6.

- ^ "No. 15192". The London Gazette. 8 October 1799. p. 1033.

- ^ "No. 15344". The London Gazette. 10 March 1801. p. 280.

- ^ "No. 15937". The London Gazette. 15 July 1806. p. 888.

- ^ "No. 15582". The London Gazette. 7 May 1803. p. 544.

- ^ a b c d e f g Winfield (2008), p. 149.

- ^ "No. 15788". The London Gazette. 12 March 1805. p. 335.

- ^ Annual biography and obituary (1827), Vol. 11, p.433. (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown).

- ^ a b "No. 15834". The London Gazette. 13 August 1805. p. 1031.

- ^ a b c d e "No. 16210". The London Gazette. 17 December 1808. pp. 1710–1712.

- ^ "No. 16171". The London Gazette. 13 August 1808. p. 1108.

- ^ "No. 16204". The London Gazette. 26 November 1808. p. 1611.

- ^ "No. 16392". The London Gazette. 31 July 1810. p. 1145.

- ^ "No. 17403". The London Gazette. 29 September 1818. pp. 1752–1153.

- ^ "No. 16650". The London Gazette. 26 September 1812. pp. 1971–1972.

References

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Guttridge, Leonard F. (2005). Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-348-9.

- James, William (January 1999). James' Naval History. Epitomised in one volume by Robert O'Byrne. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-8133-7.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- James, William (1837) The Naval History of Great Britain from the Declaration of War by France in 1793 to the Accession of George IV. (London: Richard Bentley),

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

External links

Media related to HMS St Fiorenzo (ship, 1782) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS St Fiorenzo (ship, 1782) at Wikimedia Commons