HIV/AIDS in Eswatini

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions. As of 2016, Eswatini had the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).[1][2]

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Eswatini has contributed largely to high mortality rates among productive Swazi age groups. Over the long-term, the epidemic and its respondents induced major cultural changes surrounding local practices and ideas of death, dying, and illness, as well as an expansion of life insurance and mortuary service markets and health-related non-governmental organizations.[3]

To help Eswatini and other countries across the world address HIV and AIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) developed the 95-95-95 testing and treatment targets. Local and national efforts worked towards the following three goals by 2020: 90% of people living with HIV will be aware of their HIV-positive status; 90% of those who have been diagnosed with HIV will continuously and consistently receive antiretroviral therapy (ART); and 90% of all people who are receiving ART will have viral suppression.[4] Although Eswatini has nearly achieved the testing and treatment targets of the 90–90–90 model,[4] certain populations carry a disproportionate burden.[5] The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has identified priority and key populations as the most vulnerable to HIV infection, due to epidemiological, socioeconomic, and environmental and contextual factors.[5] In particular, PEPFAR identified three priority populations in Eswatini as the focus of HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs: adolescent girls and young women (aged nine to 29), men aged 15 to 39, and orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC). PEPFAR additionally identified three key populations: men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSW), and transgender people.

Overall prevalence of HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS remains one of the major challenges to Eswatini's socioeconomic development. In 2010, "the Ministry of Labour and Social Security estimated 43 percent of the population were "inactive workers"—students, the elderly, the ill, the disabled, people who "lack capital" or "look after" their own "need"—and not part of the formal labor force."[6]

Periodic surveillance of prenatal clinics in the country has shown a consistent rise in HIV prevalence among pregnant women attending the clinics. The most recent surveillance in antenatal women reported an overall prevalence of 42.6% in 2004. Prevalence of 28% was found among young women aged 15–19. In women ages 25–29, prevalence was 56%.[7]

The Human Development Index from the UN Development Programme reports that as a consequence of HIV/AIDS, life expectancy in Eswatini has fallen from 61 years in 2000, to 32 years in 2009.[8] From another perspective, the last available World Health Organization (WHO) data (2002) shows that 64% of all deaths in the country were caused by HIV/AIDS.[9] In 2009, an estimated 7,000 people died from AIDS-related causes.[10] On a total population of approximately 1,185,000[11] this implies that HIV/AIDS kills an estimated 0.6% of the Swazi population every year. Chronic illnesses that are the most prolific causes of death in the developed world only account for a minute fraction of deaths in Eswatini; for example, heart disease, strokes, and cancer cause a total of less than 5% of deaths in Eswatini, compared to 55% of all deaths yearly in the US.[12]

The United Nations Development Program has written that if the spread of the epidemic in the country continues unabated, the "longer term existence of Eswatini as a country will be seriously threatened".[13]

History

The first reported case of HIV in Eswatini was in 1986 in the Times of Swaziland newspaper. The spread of HIV throughout Eswatini in the 1980s and 1990s coincided with the increase of migrant workers from Eswatini to the mines of South Africa.[14] "Researchers, health care and public health specialists, and policymakers all lobbied for state action since the late 1980s; the Ministry of Health established the Swaziland National AIDS Programme (SNAP) in 1987. Vusi Matsebula and Thulasizwe Hannie Dlamini registered their Emahlahlandlela (Pioneers) grassroots AIDS support group, the first in the country, as SASO, the Swaziland AIDS Support Organisation, in 1994. The year before, Hannie Dlamini publicly stated that he was HIV positive, the first person to do so in the country. Swazi women scholars Mamane Nxumalo and Phumelele Thwala were some of the first to write critically about HIV/AIDS in Swaziland, discussing how gender-unequal practices played a role in disease transmission," and "by the time SASO opened their first office in Mbabane in 1998, the national incidence rate was estimated to be 5.5 percent."[15]

Finally, King Mswati III of Eswatini declared HIV/AIDS to be a national disaster in Eswatini in February 1999.[16][17] By 1999, "there were an estimated 112,000 OVCs [orphaned and vulnerable children], almost a quarter of all children in the country; the Ministry of Education reported losing four teachers a week to AIDS-related illness, and business owners feared foreign investment losses due to decreased productivity in sick workers’ absenteeism. The Ministry of Health and Social Welfare was not able to fully finance public treatment. Even working with the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and local NGOs, they were all structurally outpaced."[18]

Cultural background

Regionally, there are many indigenous cultural practices that encourage abstinence and gender-segregated sexual and social education for youth,[19] the avoidance of premarital penetrative heterosexual contact,[20] and the avoidance of public lascivious behavior (i.e. displaying penile erections).[21]

In part, certain proponents of aspects of what is called 'traditional Swazi culture' discourage safe sexual practices, like condom use and monogamous relationships.[8] Very few men today practice the cultural ideal of polygamy. Sexual aggression is common, with 18% of sexually active high school students saying they were coerced into their first sexual encounter.[22]

National response

In 2003, the National Emergency Response Committee on HIV/AIDS (NERCHA) was established to coordinate and facilitate the national multisectoral response to HIV/AIDS, while the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) was to implement activities. The previous national HIV/AIDS strategic plan covered the period 2000–2005; a new national HIV/AIDS strategic plan and a national HIV/AIDS action plan for the 2006–2008 period are currently being developed by a broad group of national stakeholders. To date, the six key areas of the plan are prevention, care and support, impact mitigation, communications, monitoring and evaluation, and management/coordination.[7]

Despite the widespread nature of the epidemic in Eswatini, HIV/AIDS is still heavily stigmatized. Few people living with HIV/AIDS, particularly prominent people such as religious and traditional leaders and media/sports personalities, have come out publicly and revealed their status. Stigma hinders the flow of information to communities, hampers prevention efforts, and reduces utilization of services.[7]

On June 4, 2009, the US and then-Swaziland signed the "Swaziland Partnership Framework on HIV and AIDS for 2009–2014". The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) will contribute to the implementation of Eswatini's multi-sectoral "National Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS".[23] The plan was reconducted with a new eNSF (National Strategic Framework) for 2014–2018.[24]

Various community responses have been implemented as a result of this plan, consisting in the implementation of a decentralised coordination. For example, the formation of 3 regional and community structures, including Nhlangano AIDS Training Information and Counseling Center in the Shiselweni Region.[24]

The 2015 ART treatment guidelines from the Ministry of Health "mandate that after a test, patients are given HIV information in simple terms to “clarify misconceptions and myths.” They are also counseled on good nutrition, risk reduction, and where to get more information about HIV. If they test positive, they are reassured “that they can live a long healthy life.” ARVs are immediately commenced with seropositive patients who: have CD4 counts of 350 or less; are over age fifty or under age five; pregnant; have tuberculosis; and/or have a serodiscordant partner, namely a partner who is HIV negative. Opportunistic infections are treated before ART."[25]

HIV/AIDS-related disparities

Although Eswatini's multisectoral response to HIV and AIDS has obtained positive results,[5] HIV/AIDS prevalence continues to be higher and access to prevention programs continues to be lower in rural populations compared to urban populations, as well as in economically disadvantaged populations compared to economically advantaged populations.

Rural versus urban populations

The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimated that, from 2009 to 2013, 70% of urban females aged 15 to 24 had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS.[26] Only 55% of rural females in the same age group from 2009 to 2013 had access to HIV/AIDS-related knowledge.[26] Still, given the relatively small size of the country, nearly all citizens are connected by family and social networks and often move between urban and rural areas.

Economically disadvantaged versus economically advantaged populations

Data from 2009 to 2013 revealed that, out of the poorest 20% of females aged 15 to 24 in Eswatini, 49% had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS.[26] In comparison, 72% of the richest 20% of females from the same age group had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS.[26]

The gap observed among rich and poor males is comparable to the gap in comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge among rich and poor females from 2009 to 2013: 44% of the poorest 20% versus 64% of the richest 20% of Swazi males aged 15 to 24 had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS.[26]

Men aged 15 to 39

Uptake of HIV testing and treatment services presently remains low among men compared to women.[27] Furthermore, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2018, Swazi men continue to under-utilize self-testing and assisted partner notification as methods of HIV transmission prevention.[27]

“Test and Start” is an antiretroviral therapy (ART) program recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).[28] Under this program, individuals who have been diagnosed with HIV start ART soon after diagnosis, regardless of disease progression.[28] Randomized and controlled trials of Test and Start have demonstrated the program’s effectiveness in decreasing overall HIV transmission rates.[28] However, a study of Swazi men’s perceptions of Test and Start found that many men failed to seek HIV testing services due to fears of a positive result, combined with perceptions of an HIV-positive status as a death sentence.[29] The study additionally identified men’s fears of the side effects of ART as a potential barrier to initiation of and adherence to the Test and Start program.[29] Furthermore, men were uncertain of the financial stability of the Swazi government, citing doubt in the government’s ability to provide sustainable supplies of ART as a reason for not wanting to start treatment.[29] The authors of the study have recommended interventions specifically focused on Swazi men’s perceptions of HIV testing and treatment, including targeted counseling and education that address concerns about early initiation of ART, social consequences of accessing ART services, and capacity of the Swazi government to tackle HIV/AIDS-related issues.[29]

Marginalized, neglected, and vulnerable populations

Interventions serving the general Swazi population, such as campaigns and initiatives encouraging voluntary medical male circumcision, promoting greater treatment uptake and adherence, and providing risk-reduction counseling, have contributed to major reductions in HIV transmission and acquisition rates.[30] However, these interventions for the general population may not be as effective for marginalized populations facing greater than average stigmatization, including female sex workers (FSW), men who have sex with men (MSM), and transgender people.[5] Other populations, such as children living with HIV and orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC), are left vulnerable by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and societal forces.

Female sex workers (FSW)

Even in the context of a generalized HIV epidemic in Eswatini, in which HIV prevalence is higher among women than men in the general population, female sex workers (FSW) in Eswatini carry an even more disproportionate burden.[30] The FSW population is largely understudied and underserved, which has resulted in poor characterization of specific HIV prevention, treatment, and care needs for FSW, as well as sparse provision and uptake of health resources. This limited uptake is due partly to fear of disclosure of sex work status.[31] Sex work in Eswatini is illegal. Due to criminalization of sex work, it is particularly difficult to reach the female and male sex worker population.[31] The 2016 Eswatini HIV country profile from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated the prevalence of HIV among sex workers (both female and male) to be 61%.[32]

A study of 328 FSW in Eswatini, conducted between August 2011 to October 2011, found that about 75% of the FSW living with HIV who participated in the survey were aware of their status.[30] Even so, only 40% of these women reported to be receiving treatment.[30] In addition to these statistics, the study found that HIV-positive FSW who were aware of their status, compared to HIV-negative FSW, were not more likely to wear condoms.[30] Overall, the study's FSW had limited knowledge of safe-sex practices, with only three participants aware that anal sex carries the highest risk of HIV transmission.[30] Although 86% of the survey sample reported to have received HIV prevention information in the past 12 months, only about half of the sample reported to have access to specialized HIV prevention programs for sex workers.[30] A large portion (73%) of the survey's participants reported to have experienced any event of stigma.[30] Furthermore, this sense of stigmatization is reflected in the low rates of disclosure of their sex work to family members and healthcare workers.[30]

To address the lack of specialized HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs for FSW, some studies have explored potential avenues for intervention. For instance, a study found that higher levels of social cohesion and social participation among a sample of FSW in Eswatini was positively associated with protective behaviors, such as consistent condom use, HIV testing in the previous year, and collective engagement with other sex workers in HIV-related meetings and talks.[33] At the same time, the same study found higher levels of social cohesion and social participation to be inversely associated with HIV-related risk factors, such as experiences of social discrimination and physical, sexual, and emotional violence.[33]

Men who have sex with men (MSM)

HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) aged 16 to 44 years is 17.7% in Eswatini, with the HIV prevalence increasing with age in this group.[5] MSM represent a neglected population: HIV/AIDS data for MSM are less robust than for the general Swazi population, and the government of Eswatini has only just recently directed public funding towards programs aimed specifically at addressing the epidemic among MSM.[34] MSM face criminalization, stigma, and discrimination when accessing HIV/AIDS services.[34] Although no laws in Eswatini specifically prohibit homosexuality, same-sex practices can be charged as indecent acts under common law, and these practices are widely regarded as illegal under the Sodomy Act.[35]

More than a third of MSM in Eswatini reported having been tortured due to their sexual orientation, as found in a study published by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Research to Prevention program.[36] One-fifth of respondents in this study also believed they had received lower quality medical care due to their orientation. MSM also reported having experienced other rights violations related to their sexual practices, such as denial of care, police-mediated violence, as well as verbal and/or physical harassment.[36]

Such barriers to access are linked to lower levels of HIV/AIDS-related information, education, and communication services uptake among MSM, as compared with other reproductive-age adults, thus resulting in limited knowledge of HIV/AIDS-related risks associated with same-sex practices.[34][37] For instance, in a study of 324 Swazi MSM, participants were significantly more likely to have received information about HIV transmission via sex with women, rather than during sex with other men.[37] The limited availability of relevant HIV/AIDS information for MSM could perpetuate ignorance regarding same-sex HIV transmission.[37] Among this study’s sample, there were lower rates of condom use with male sexual partners as compared to female sexual partners, further emphasizing the need for specific information about same-sex HIV acquisition and transmission.[37] Only about half of the study’s respondents expressed concern about HIV.[37] Furthermore, only a quarter of men living with HIV who participated in the study were aware of their HIV-positive status.[37] The provision of healthcare services for MSM and research into HIV/AIDS among MSM are largely concentrated in urban regions. Although the HIV/AIDS situation has been reported to improve for MSM in urban regions of Eswatini, the situation has worsened in rural regions, where strong stigma associated with same-sex practices persists.[35][38]

Children living with HIV and orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC)

It has been estimated that there are 15,000 children aged zero to 14 living with HIV.[32] While the antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage for adults was approximately 80% in 2016, the estimated ART coverage for children was considerably lower, at 64%.[32] Since 2016, the coverage for children has increased to 75%, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).[27]

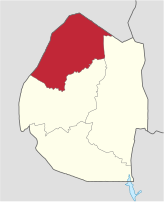

Increased mortality rates due to the high prevalence of HIV and AIDS in Eswatini have also contributed to a growing number of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) as well as child-headed households. This however changed in 2019 due to government financial support.[27][39] OVC are, compared to their peers, at increased risk of experiencing negative outcomes, such as loss of their education, food insecurity, malnutrition, and morbidity.[39][40] The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimated in 2013 that approximately 70% of Swazi orphans lost their parents to AIDS.[26] Among Eswatini's four regions, the highest number of OVC are found in Lubombo (35.9%).[41] This is followed by 35.5% in Shiselweni, 33.2% in Manzini, and 21.6% in Hhohho.[41]

A program funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) was designed to economically empower female caregivers of OVC in rural Eswatini.[42] The program has been shown to have had a positive impact on child protection, well-being, and health.[42] Women enrolled in the intervention participated in activities related to care and support of OVC and HIV prevention, as well as activities focused on saving and lending principles, group savings, establishment and sustenance of small business, marketing, and income generation.[42] The intervention helped female caregivers of OVC in the development of income-generating micro-enterprises, while creating a platform through which these women could learn and discuss with one another about meeting the overall health, sexual and reproductive health, psychosocial, and education needs of their OVC.[42] In general, the Swazi government has been successful in improving school attendance while simultaneously providing psychosocial and economic supports to OVC outside of school.[43] However, a study analyzing the relationship between household characteristics and the schooling status of OVC in Eswatini found that non-OVC are statistically significantly more likely than OVC to attend school.[44] The same study found that OVCs belonging to socioeconomically disadvantaged households as well as OVCs living in urban regions were less likely to attend school.[44]

Other HIV/AIDS-affected populations

Healthcare workers

The HIV pandemic in Eswatini does not spare healthcare workers, among which utilization of HIV/AIDS services is low.[45][46] Fears of HIV-related stigma are prevalent among members of the healthcare workforce.[45] Such stigma serves as a significant barrier for healthcare workers to accessing and utilizing HIV/AIDS care and prevention services at their own workplace and other facilities. In particular, workers have cited a fear of stigmatization by both their patients and colleagues, and a fear of breach of confidentiality, as reasons for deciding not to access HIV testing or care.[45] Self-stigmatization is exacerbated among healthcare workers.[45] They view themselves as separate from and more knowledgeable than the HIV-vulnerable general population, which enforces a professional need to be HIV free.[45] Many HIV-positive healthcare workers feel a sense of failure and professional embarrassment, as they have contracted an infection that they have been trained to avoid and prevent.[45]

The public health sector in Eswatini faces a shortage of healthcare workers, with many health workers overwhelmed by the demand for care.[46] This depletion of the healthcare workforce has been attributed partly to HIV/AIDS.[45][46] In fact, the prevalence of HIV among healthcare workers is estimated to be equal to that among the general Swazi population.[45] The self-stigmatization of HIV/AIDS care among healthcare workers prevents healthcare workers from accessing needed care,[46] which can contribute to HIV-related death and absenteeism of healthcare providers.[45]

Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS

Since the early 1990s, Eswatini has been depending on food aid from other countries to feed its population.[47] Furthermore, the Swazi government declared a national drought disaster in February 2016, seventeen years after its declaration of HIV/AIDS as a national disaster.[48] Food shortages caused by the El Niño-induced drought left more than 300,000 people food insecure.[48]

In southern Africa, lack of food security has not only been linked to an increased risk of acquiring HIV, but also increased difficulty remaining healthy for people living with HIV.[49] In particular, in southern Africa, food insecurity has been linked to high-risk sexual behaviors among women, including practices such as decreased condom use, transactional sex, and sex work.[49] Food insecurity has also been linked to decreased adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and rapid HIV progression.[49] ART has also been found to be less effective at maintaining CD4 cell counts, an indication of the health of one's immune system, in individuals suffering from malnutrition or food insecurity.[50]

The relationship between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS is bidirectional. Not only does food insecurity often drive individuals in Eswatini to engage in behaviors that may increase their risk of acquiring HIV, HIV/AIDS is argued by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and World Food Programme (WFP) to be the primary underlying driver of food insecurity among Swazi households, as it limits Swazis’ productivity and ability to generate income.[47]

In fact, female Swazi sex workers living with HIV have reported being caught in a cycle of hunger, HIV, and sex work.[47][49] Many women in Eswatini experiencing poverty and food insecurity resort to sex work in order to secure sufficient food for themselves and their families.[49] Engagement in sex work increases their risk of acquiring HIV.[49] Many sex workers who are living with HIV then attempt to manage their infection and to prevent side effects from ART by trying to secure more food, especially more healthy food. This increased dependence on food also leads many of the women to increasingly depend on the income generated from sex work.[49]

HIV and tuberculosis (TB) co-infection

Eswatini not only has the highest adult HIV prevalence globally, it also has the second highest rate of HIV-tuberculosis (TB) co-infection in the world.[51] Accompanying this statistic, TB-related mortality in people living with HIV in Eswatini (135 deaths per 100,000) is significantly higher than TB-related mortality among the general Swazi population (51 deaths per 100,000).[51]

Over the past decade, the country has taken steps to strengthen collaborative HIV-TB services and interventions. For example, it was documented in 2014 that 97% of Swazi patients with TB who know their HIV status are HIV positive.[51] As of 2017, this percentage has fallen to 70%.[52] As Eswatini has expanded antiretroviral therapy (ART) and other HIV care and prevention services, notification rates of TB have coincidentally declined.[53] In 2014, only 79% of HIV-positive TB patients initiated ART.[51] As of 2017, this percentage has increased to 94%.[52] TB incidence has declined at an average annual rate of 18% from 2010 to 2017 in Eswatini, among the fastest rates in recent decades.[52]

One example of such public health advancements is the establishment of facilities offering both TB and HIV services in the Hhohho, Manzini, Lubombo, and Shiselweni regions of Eswatini.[51] ART clinics, in addition to offering routine HIV services, are offering TB screening, diagnosis, and preventive therapy to patients. Likewise, TB clinics, in addition to offering routine TB services are offering HIV testing, preventive therapy, and services for ART initiation and follow-up.[51] A 2018 retrospective study assessing the provision of HIV and TB services in Eswatini's co-located HIV and TB clinics concluded that there is a high rate of timely ART uptake among TB patients whose HIV-positive status is known.[51]

More than one-third of Swazi women between the ages of 15 and 49 are living with HIV;[30] this is accompanied by high HIV-TB co-infection rates in Eswatini, placing women at greater risk of contracting TB compared to men. Given this statistic, the Swazi government is taking steps to integrate TB screening, prevention, and treatment with women’s health services along with routine HIV services for women.[54] As of March 2019, non-medical staff called “cough officers” who screen patients for TB are now part of routine care for women visiting clinics for family planning, prenatal care, or well-child check-ups.[54]

Despite the significant increases in ART coverage for HIV-positive TB patients in Eswatini, provision of TB preventive treatment to people newly enrolled in HIV care has remained at 1% in the country as of 2017.[52]

See also

References

- ^ "Swaziland 2016 Country factsheet". UNAIDS. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "Prevalence of HIV, total (% of population ages 15-49)". The World Bank. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ Golomski, Casey (2018-06-04). Funeral Culture: AIDS, Work, and Cultural Change in an African Kingdom. Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 9780253036469. OCLC 1039318343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2014). 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic

- ^ a b c d e U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. (2018). Swaziland Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary.

- ^ Golomski, Casey (2018-06-04). Funeral Culture : AIDS, Work, and Cultural Change in an African Kingdom. Bloomington, Indiana. p. 58. ISBN 9780253036469. OCLC 1039318343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Health Profile: Swaziland" Archived 2008-08-17 at the Wayback Machine. United States Agency for International Development (June 2005).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Swaziland: A culture that encourages HIV/AIDS". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN). 15 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ Swaziland, Mortality Country Fact Sheet 2006. WHO. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed November 22, 2009 - ^ UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010 Annex 1 - HIV and AIDs estimates and data, 2009 and 2001. UNAIDS. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed October 6, 2011 - ^ World Population Prospects: 2008 Revision. United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2008/wpp2008_text_tables.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2011

- ^ Causes of death in US, 2006. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_14.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2009.

- ^ Country programme outline for Swaziland, 2006-2010. United Nations Development Program. http://www.undp.org.sz/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=19&Itemid=67 Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed November 22, 2009

- ^ Crush, Jonathan (2010). Migration-Induced HIV and AIDS in Rural Mozambique and Swaziland. Idasa. ISBN 978-1-920409-49-4.

- ^ Golomski, Casey (2018). Funeral Culture: AIDS, Work, and Cultural Change in an African Kingdom. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780253036452.

- ^ Wyngaard, Arnau van; Root, Robin; Whiteside, Alan (2017-07-04). "Food insecurity and ART adherence in Swaziland: the case for coordinated faith-based and multi-sectoral action". Development in Practice. 27 (5): 599–609. doi:10.1080/09614524.2017.1327026. hdl:2263/64318. ISSN 0961-4524. S2CID 157916875.

- ^ "AIDS in Swaziland", Radio Netherlands Archives, July 10, 2000

- ^ Golomski, Casey (2018-06-04). Funeral culture : AIDS, work, and cultural change in an African kingdom. Bloomington, Indiana. p. 39. ISBN 9780253036469. OCLC 1039318343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Golomski, Casey (2018-06-04). Funeral culture : AIDS, work, and cultural change in an African kingdom. Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 9780253036469. OCLC 1039318343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hunter, Mark. (2010). Love in the time of AIDS : inequality, gender, and rights in South Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253004819. OCLC 680017828.

- ^ Golomski, Casey; Nyawo, Sonene (2017-08-03). "Christians' cut: popular religion and the global health campaign for medical male circumcision in Swaziland". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 19 (8): 844–858. doi:10.1080/13691058.2016.1267409. ISSN 1369-1058. PMID 28074706. S2CID 39361080.

- ^ "Swaziland HIV/AIDS health profile" (PDF). USAID. September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-10. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ "Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Swaziland". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Swaziland global AIDS response progress reporting 2014" (PDF). Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Golomski, Casey (2018-06-04). Funeral culture : AIDS, work, and cultural change in an African kingdom. Bloomington, Indiana. p. 58. ISBN 9780253036469. OCLC 1039318343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f UNICEF (Ed.). (2014). Reimagine the future: innovation for every child. New York, NY: UNICEF.

- ^ a b c d UNAIDS. (2018). UNAIDS Data 2018 (UNAIDS Data). Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf

- ^ a b c Reis, Ria; Shabalala, Fortunate; Simelane, Njabulo; Masilela, Nelisiwe; Vernooij, Eva; Pell, Christopher (2018-03-01). "False starts in 'test and start': a qualitative study of reasons for delayed antiretroviral therapy in Swaziland". International Health. 10 (2): 78–83. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihx065. ISSN 1876-3413. PMID 29342259.

- ^ a b c d Adams, Alfred K.; Zamberia, Agostino M. (December 2017). ""I will take ARVs once my body deteriorates": an analysis of Swazi men's perceptions and acceptability of Test and Start". African Journal of AIDS Research. 16 (4): 295–303. doi:10.2989/16085906.2017.1362015. ISSN 1727-9445. PMID 29132279.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Baral, Stefan; Ketende, Sosthenes; Green, Jessie L.; Chen, Ping-An; Grosso, Ashley; Sithole, Bhekie; Ntshangase, Cebisile; Yam, Eileen; Kerrigan, Deanna (2014-12-22). "Reconceptualizing the HIV Epidemiology and Prevention Needs of Female Sex Workers (FSW) in Swaziland". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e115465. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5465B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115465. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4274078. PMID 25531771.

- ^ a b Chipamaunga, Shalote; Muula, Adamson S; Mataya, Ronald (October 2010). "An assessment of sex work in Swaziland: barriers to and opportunities for HIV prevention among sex workers". SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 7 (3): 44–50. doi:10.1080/17290376.2010.9724968. ISSN 1729-0376. PMC 11133881. PMID 21409304.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization. (2017). Swaziland (HIV Country Profile 2016). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hiv/data/Country_profile_Swaziland.pdf

- ^ a b Baral, Stefan; Kennedy, Caitlin E.; Ketende, Sosthenes; Mnisi, Zandile; Kerrigan, Deanna; Fonner, Virginia A. (2014-01-31). "Social Cohesion, Social Participation, and HIV Related Risk among Female Sex Workers in Swaziland". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e87527. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987527F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087527. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3909117. PMID 24498125.

- ^ a b c Sithole, Bhekie (2017-10-02). "HIV prevention needs for men who have sex with men in Swaziland". African Journal of AIDS Research. 16 (4): 315–320. doi:10.2989/16085906.2017.1379420. ISSN 1608-5906. PMID 29132291.

- ^ a b The Foundation for AIDS Research. (2013). Country Profile: Swaziland (Achieving an AIDS-Free Generation for Gay Men and Other MSM in Southern Africa). Retrieved from https://www.amfar.org/uploadedFiles/_amfarorg/Articles/Around_The_World/GMT/2013/MSM%20Country%20Profiles%20Swaziland%20092613.pdf Archived 2022-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b U.S. Agency for International Development. (2013). HIV among Female Sex Workers and Men Who Have Sex with Men in Swaziland: A combined report of quantitative and qualitative studies. Retrieved from https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/research-to-prevention/publications/Swazi-integrated-report-final.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f Baral, Stefan D.; Ketende, Sosthenes; Mnisi, Zandile; Mabuza, Xolile; Grosso, Ashley; Sithole, Bhekie; Maziya, Sibusiso; Kerrigan, Deanna L.; Green, Jessica L. (2013). "A cross-sectional assessment of the burden of HIV and associated individual- and structural-level characteristics among men who have sex with men in Swaziland". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 16 (4S3): 18768. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.4.18768. ISSN 1758-2652. PMC 3852353. PMID 24321117.

- ^ Imrie, John; Hoddinott, Graeme; Fuller, Sebastian; Oliver, Stephen; Newell, Marie-Louise (2013-05-01). "Why MSM in Rural South African Communities Should be an HIV Prevention Research Priority". AIDS and Behavior. 17 (1): 70–76. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0356-1. ISSN 1573-3254. PMC 3627851. PMID 23196857.

- ^ a b Thwala, S’lungile K. (2018-06-27). "Experiences and Coping Strategies of Children From Child-Headed Households in Swaziland". Journal of Education and Training Studies. 6 (7): 150–158. doi:10.11114/jets.v6i7.3393. ISSN 2324-8068.

- ^ Arora, Shilpa Khanna; Shah, Dheeraj; Chaturvedi, Sanjay; Gupta, Piyush (2015). "Defining and Measuring Vulnerability in Young People". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 40 (3): 193–197. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.158868. ISSN 0970-0218. PMC 4478662. PMID 26170545.

- ^ a b Owaga, E. E.; Masuku-Maseko, S. K. S. (2012-01-01). "Child malnutrition and mortality in Swaziland: Situation analysis of the immediate, underlying and basic causes". African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. 12 (2): 5994–6006–6006. doi:10.18697/ajfand.50.11710. ISSN 1684-5374. S2CID 240472680.

- ^ a b c d Makufa, Syloid Choice; Kisyombe, Daisy; Miller, Nicole; Barkey, Nanette (2017-10-02). "Empowering caregivers of orphans and vulnerable children in Swaziland". African Journal of AIDS Research. 16 (4): 355–363. doi:10.2989/16085906.2017.1387579. ISSN 1608-5906. PMID 29132285.

- ^ Whiteside, Alan; Vinnitchok, Andriana; Dlamini, Tengetile; Mabuza, Khanya (December 2017). "Mixed results: the protective role of schooling in the HIV epidemic in Swaziland". African Journal of AIDS Research. 16 (4): 305–313. doi:10.2989/16085906.2017.1362016. ISSN 1727-9445. PMID 29132280.

- ^ a b Dlamini, Bongiwe N.; Chiao, Chi (2015-09-02). "Closing the health gap in a generation: exploring the association between household characteristics and schooling status among orphans and vulnerable children in Swaziland". AIDS Care. 27 (9): 1069–1078. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1026306. ISSN 0954-0121. PMID 25830786. S2CID 46876949.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vries, Daniel H. de; Galvin, Shannon; Mhlanga, Masitsela; Cindzi, Brian; Dlamini, Thabsile (2011). ""Othering" the health worker: self-stigmatization of HIV/AIDS care among health workers in Swaziland". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 14 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-14-60. ISSN 1758-2652. PMC 3287109. PMID 22192455.

- ^ a b c d Kober, Katharina; Van Damme, Wim (2006-05-31). "Public sector nurses in Swaziland: can the downturn be reversed?". Human Resources for Health. 4: 13. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-4-13. ISSN 1478-4491. PMC 1513248. PMID 16737544.

- ^ a b c Frayne, B. et al. (2010). The State of Urban Food Insecurity in Southern Africa (rep., pp. 1-54). Kingston, ON and Cape Town: African Food Security Urban Network. Urban Food Security Series No. 2.

- ^ a b Ministry of Health. (2016). Swaziland Comprehensive Drought Health and Nutrition Assessment Report. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/wfp283963.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g Fielding-Miller, Rebecca; Mnisi, Zandile; Adams, Darrin; Baral, Stefan; Kennedy, Caitlin (2014-01-25). ""There is hunger in my community": a qualitative study of food security as a cyclical force in sex work in Swaziland". BMC Public Health. 14 (1): 79. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-79. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 3905928. PMID 24460989.

- ^ Anema, Aranka; Vogenthaler, Nicholas; Frongillo, Edward A.; Kadiyala, Suneetha; Weiser, Sheri D. (November 2009). "Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities". Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 6 (4): 224–231. doi:10.1007/s11904-009-0030-z. ISSN 1548-3576. PMC 5917641. PMID 19849966.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pathmanathan, Ishani; Pasipamire, Munyaradzi; Pals, Sherri; Emily, Dokubo; Preko, Peter; Trong, Ao; Mazibuko, Sikhathele; Ongole, Janet; Dhlamini, Themba (2018-05-16). "High uptake of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive TB patients receiving co-located services in Swaziland". PLOS ONE. 13 (5): e0196831. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1396831P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196831. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5955520. PMID 29768503.

- ^ a b c d World Health Organization. (2018). Global tuberculosis report 2018. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- ^ Haumba, S.; Dlamini, T.; Calnan, M.; Ghazaryan, V.; Smith-Arthur, A. E.; Preko, P.; Ehrenkranz, P. (2015-06-21). "Declining tuberculosis notification trend associated with strengthened TB and expanded HIV care in Swaziland". Public Health Action. 5 (2): 103–105. doi:10.5588/pha.15.0008. PMC 4487488. PMID 26400378.

- ^ a b "New, More Convenient Tuberculosis Services Are Saving Women's Lives in Eswatini". ICAP at Columbia University. March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2019.