Archives Nationales (France)

| Archives nationales | |

|---|---|

Top: Façade of Hôtel de Soubise, the historic site of the National Archives in the Marais district of Paris, where pre-French Revolution records are kept. Bottom: National Archives' new site at Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, where post-French Revolution records are kept. | |

| |

| 48°51′37″N 2°21′34″E / 48.86029568613751°N 2.359355640417249°E and 48°56′54″N 2°21′53″E / 48.94825818490026°N 2.364806794181443°E | |

| Location | Paris and Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, France |

| Established | 1790 |

| Collection size | 383 km (physical records)(as of 2022) 74.75 terabytes (electronic archives) (as of end 2020) |

| Period covered | AD 625 - present |

| Website | www |

The Archives nationales (French pronunciation: [aʁʃiv nɑsjɔnal]; abbreviated AN; English: National Archives) are the national archives of France. They preserve the archives of the French state, apart from the archives of the Ministry of Armed Forces and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as these two ministries have their own archive services, the Defence Historical Service (SHD) and Diplomatic Archives respectively. The National Archives of France also keep the archives of local secular and religious institutions from the Paris Region seized at the time of the French Revolution (such as local royal courts of Paris, suburban abbeys and monasteries, etc), as well as the archives produced by the notaries of Paris during five centuries, and many private archives donated or placed in the custody of the National Archives by prominent aristocratic families, industrialists, and historical figures.

The National Archives have one of the largest and oldest archival collections in the world. As of 2022, they held 383 km (238 mi) of physical records (the total length of occupied shelves put next to each other) from the year 625 to the present time, and as of 2020 74.75 terabytes (74,750 GB) of electronic archives.[2]

To deal with this massive volume of documents, the National Archives currently operate from two sites in the Paris Region: the historical site of the National Archives in the heart of Paris (in the Medieval Marais district), which contains the physical records of the French state from before the French Revolution as well as the records of the Paris notaries from all periods, and the newer site at Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, in the northern suburbs of Paris, opened in 2013, which contains all the physical records of the French state since the French Revolution, as well as the private archives from all periods.

Two sister agencies, the National Overseas Archives (ANOM) and the National Archives of the World of Labour (ANMT) are located in Aix-en-Provence and in Roubaix respectively. These are managed separately from the National Archives.

History

The Archives nationales are heir to the Trésor des chartes ("Charters Treasury"), the archives of the French crown that were kept in the ancient Capetian royal palace on the Île de la Cité until the French Revolution, although the Trésor des chartes was more limited in scope than the current Archives nationales, since it contained only charters and legal records constituting title deeds for the French crown, used to establish the rights of French kings over crown lands. The Trésor des chartes today still forms one of the most renowned archival series in the collections of the National Archives.

The Archives nationales were created at the time of the French Revolution in 1790. It was a state decree of 1794 that made it mandatory to centralise all the pre-French Revolution private and public archives seized by the revolutionaries, completed by a law passed in 1796 which created departmental archives (archives départementales) in the departments of France to alleviate the burden on the Archives nationales in Paris, thus creating the collections of the French archives as we know them today. In 1800 the Archives nationales became an autonomous body of the French state.

Archives of France

The National Archives are under the authority of the Archives of France administration (Service interministériel des Archives de France) in the Ministry of Culture. The Archives of France also manage the 101 departmental archives located in the prefectures of each of the 100 departments of France plus the city of Paris, as well as various other local (municipal) archives, plus 12 more recent regional archives (which store the archives of the regional councils and their agencies). The departmental and local archives contain all the archives from the deconcentrated branches of the French state, as well as all the archives of the pre-French Revolution provincial and local institutions seized by the revolutionaries (parliaments, chartered cities, abbeys, and churches).

In addition to the 459 kilometres (285 mi) of physical records and 74.75 terabytes of electronic archives kept by the National Archives and its sister agencies, the National Overseas Archives (ANOM) in Aix-en-Provence and the National Archives of the World of Labour (ANMT) in Roubaix, this as of the end of 2020 (373 km and 74.75 TB at the National Archives strictly speaking, and 86 km at ANOM and ANMT), another 3,591 kilometres (2,231 mi) of physical records and 225.25 terabytes of electronic archives were kept in the regional, departmental and local archives in the end of 2020,[2] in particular the church records and notarial records used by genealogists.

The archives of the Ministry of Armed Forces (Defence Historical Service, ca. 450 kilometres (280 mi) of physical records) and the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Diplomatic Archives , ca. 120 kilometres (75 mi) of physical records) are managed separately by their respective ministries and do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Archives of France administration.[3]

Collections

The National Archives have one of the largest and most important archival collections in the world.[citation needed] As of 2022, the National Archives contained 383 km (238 mi) of physical records (the total length of occupied shelves put next to each other) and as 2020 74.75 terabytes (74,750 GB) of electronic archives,[2] an enormous mass of documents growing every year (3.1 km of physical records and 4.7 terabytes of electronic archives entered the National Archives in 2020 despite the COVID-19 lockdowns).[4]

Due to the events of the French Revolution, the pre-French Revolution archives kept by the National Archives are not just the archives of the central state, but also the many local archives of the Paris region, such as all the archives of the abbeys surrounding Paris (e.g. the Royal Abbey of St Denis), the archives of the churches of Paris, and the archives of the medieval Paris city hall. Thus, the National Archives serve as the archives of the French central state for records from 1790 onwards, but for records before 1790 they serve as both the archives of the central state and the local archives of Paris and its region. The National Archives, however, do not keep the pre-1790 church records of Paris (baptisms, marriages and burials). These were kept at the municipal archives of Paris (original series from 16th century to French Revolution) and at the Palais de Justice (duplicate registers from 1700 to French Revolution), and were entirely destroyed by fires set by extremists at the end of the Paris Commune in May 1871 which destroyed both the municipal archives and a large part of the Palais de Justice.

The oldest original record kept at the National Archives is a papyrus dated AD 625 coming from the archives of the Royal Abbey of St Denis seized at the time of the French Revolution. This papyrus is the confirmation by King Chlothar II of a grant of land in the city of Paris to the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis previously made by the vir illustris Dagobert, son of Baddo. This charter is the oldest original one kept by the National Archives, but the National Archives possess medieval copies of earlier records from the 6th century (but not the originals). The National Archives also possess a small fragment of an original papyrus record from the year 619 or 620 (uncertain date), a private donation, probably to the basilica of St Denis, but the charter from 625 is the oldest one preserved in its entirety.

The National Archives keep 211 authentic, original records from the 1st millennium (later copies and forgeries not included).[5] The oldest Merovingian records are all written on papyrus imported from Egypt, in continuation of Roman practices. Records written on parchment appear after 670, due to the Muslim conquest of the Southern Mediterranean, and completely replace papyrus records within a few decades.[6][7]

Detail of the 211 authentic, original records from before the year 1000 kept by the National Archives:[5][8][9]

| Years | Number of authentic records |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 600-649 | 9 | Oldest record: year 625 (also fragment of an earlier record from 619/620). All written on papyrus. |

| 650-699 | 27 | 8 written on papyrus; 19 written on parchment. |

| 700-749 | 10 | All written on parchment. |

| 750-799 | 40 | 38 written on parchment; 2 written on papyrus. |

| 800-849 | 50 | All written on parchment. |

| 850-899 | 51 | 49 written on parchment; 2 written on papyrus. |

| 900-949 | 12 | All written on parchment. |

| 950-999 | 12 | All written on parchment. |

In total, the National Archives possess 47 original records from the Merovingian period (ended in 751). They also possess 5 original records from the reign of Pepin the Short (751–768), 31 from the reign of Charlemagne (768-814), 28 from the reign of Louis the Pious (814-840), 69 from the reign of Charles the Bald (840-877), 4 from the reign of Hugh Capet (987–996), 21 from the reign of Robert the Pious (996–1031), and then a rapidly increasing number of original records after Robert the Pious, with for example more than 1,000 original records from the reign of Philip Augustus (1180–1223) and several thousand original records from the reign of Saint Louis (1226–1270).

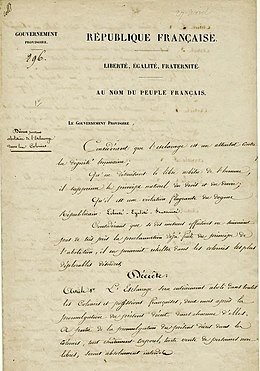

The National Archives also hold the original draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, dating from 1789, a core statement of the values of the French Revolution which had a major impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide. It was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme Register in 2003 in recognition of its historical significance.[10]

Sites

Due to the massive volume of documents and records kept by the National Archives, these have been divided among two sites, one in the historic center of Paris, the other one in the northern Parisian suburb of Pierrefitte-sur-Seine (opened in 2013), complemented by a microform centre at the Château d'Espeyran, in Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, serving as a back-up in case original documents are destroyed. A third site in the Paris Region, at Fontainebleau, was closed in 2016 and its content moved to Pierrefitte-sur-Seine.

Paris

The National Archives has been located since 1808 in a group of buildings comprising the Hôtel de Soubise and the Hôtel de Rohan in the district of Le Marais in the centre of Paris.

Since the opening of the Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site in 2013, the historic Paris site stores only the documents and records from before the French Revolution, as well as the so-called Minutier central of Paris, i.e. the archives of all the Parisian notaries extending from the 15th century to the beginning of the 20th century.[11] Since 1867 it has also housed the Musée des Archives Nationales.

In 2004, the Paris site of the National Archives kept 98.3 kilometres (61.1 mi) of physical records: 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) of pre-French Revolution archives; 52 kilometres (32 mi) of records of the French central state from 1790 to 1958; 20 kilometres (12 mi) of Paris notary records (Minutier central); 5.8 kilometres (3.6 mi) of private archives, notably the archives of the aristocratic families seized at the time of the French Revolution; 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) of books; and finally 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of ancient maps and plans.

In 2012-2013, all archives, maps and plans from 1790 to the 20th century, as well as all private archives from all periods, were moved to the new site of Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, and as a result the amount of archives stored at the historic Paris site was reduced to 45.8 kilometres (28.5 mi) of physical records (situation as of the end of 2015).[12]

The space liberated by the departure of more than 50 km of records allowed the National Archives to resume the collection of archives from the Paris notaries, in particular late 19th and early 20th centuries records which hadn't been collected yet. As of 2022, the Minutier central of the Paris notaries stored at the National Archives was filling 23.8 kilometres (14.8 mi) of shelves, representing 20 million notary records from the 1460s to the first half of the 20th century.[13]

Pierrefitte-sur-Seine

The construction of a new National Archives centre at Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, in the northern suburbs of Paris, was decided in 2004 to alleviate the burden on the historic Paris sites of the National Archives as well as on the newer Fontainebleau site. Designed by the Italian architect Massimiliano Fuksas, it opened to the public in January 2013.[14] It was meant to become the main site of the National Archives, with a capacity of 380 kilometres (240 mi) of shelves, one of the largest storage capacities in the world.[14]

In 2012-2013, more than 50 km of records from the historic Paris site and 150 km of records from the newer Fontainebleau site were moved to the new Pierrefitte site. By the end of 2015, the Pierrefitte site kept 219.5 kilometres (136.4 mi) of records.[12] The decision to close the Fontainebleau site in 2016 after the discovery of structural issues in 2014 has led to the transfer of all Fontainebleau's remaining archives to the Pierrefitte site, a transfer that was to be completed in 2022,[15] at which point the Pierrefitte site of the National Archives would store more than 300 kilometres (190 mi) of physical records, close to maximum capacity, at a much earlier date than was originally anticipated. As a result, the National Archives have launched the construction of new storage capacity (100 km of shelves) at the Pierrefitte site, which should bring the total capacity of the Pierrefitte site to 480 kilometres (300 mi) of shelf space by 2026.[16]

The Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site of the National Archives stores all the archives of the French central state since 1790 (except those of the Ministry of Armed Forces and of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which have their own archive agencies, the Defence Historical Service and the Diplomatic Archives respectively), as well as all the private archives from all periods seized during the French Revolution or deposited at the National Archives since then (archives of aristocratic families, industrialists, major historical figures, etc).[11] The Pierrefitte site will receive all the new records from the central state every year for the next 30 years after its opening.

Fontainebleau

The Centre for Contemporary Archives (Centre des archives contemporaines or CAC), founded as the Cité interministérielle des archives, opened in Fontainebleau in 1969. It was the repository for documents produced by the French central state since 1958 (founding of the Fifth Republic). In 2006 it contained 193 kilometres (120 mi) of physical records. The Fontainebleau site also stored the electronic archives collected by the National Archives, as well as the audio and video files kept by the National Archives.

With the construction of the new Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site of the National Archives, it was decided to transfer most of the archives stored at Fontainebleau to Pierrefitte, and to keep at Fontainebleau only the electronic archives, the audio and video files, as well as some series of physical records concerning specific individuals, such as naturalization records or the career files of government employees, representing an estimated 60 km of shelf space.[11]

After the discovery of structural issues with the buildings at the Fontainebleau site in 2014, it was decided to permanently close the Fontainebleau site in 2016, and move all the remaining physical records stored there to the Pierreffitte site of the National Archives.[17] The removal of more than 70 km of records to Pierrefitte was due to be completed by 2022.[15]

Espeyran

The National Microfilm Centre (Centre national du microfilm), opened in the Château d'Espeyran, in Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, in 1973. This centre stores original microforms of documents held in other archive centres, both national and departmental, in case the original documents were destroyed. This centre keeps approximately 61 million views of original documents.

Sister agencies

National Overseas Archives (ANOM)

The National Overseas Archives (Archives nationales d'outre-mer or ANOM), originally the Centre for Overseas Archives (Centre des archives d'outre-mer), opened in Aix-en-Provence in 1966. It stores the archives from the ministries in charge of the French colonies and Algeria until the 1960s (such as the Ministry of Colonies) as well as the archives transferred from the French colonies and Algeria at the time of their independence between 1954 and 1962. The ANOM also possesses private and corporate archives related to the former French colonies and Algeria. In total the ANOM keeps 36.5 kilometres (22.7 mi) of archives[4] from the 17th to the 20th century covering more than 40 currently independent countries spread over 5 continents. Note that the archives concerning Tunisia and Morocco, which were protectorates and not colonies, are kept by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in its Diplomatic Archives.

In addition to these 36.5 km of archives, the ANOM also possesses 60,000 maps and plans going back to the 17th century, 150,000 photographs, 20,000 postcards, and 100,000 books.

National Archives of the World of Labour (ANMT)

The National Archives of the World of Labour (Archives nationales du monde du travail or ANMT), originally the Centre for the Archives of the World of Labour (Centre des archives du monde du travail), opened in Roubaix in 1993. It stores the archives of businesses, trades unions, associations and corporations, and architects. In total it contains 49.8 kilometres (30.9 mi) of archives (as of 2020).[4] Most of the archives at the ANMT are private archives.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Grands Documents de l'Histoire de France, Archives Nationales de France, p.38, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Activité des services d'archives en France : données 2020 - Conservation et restauration". francearchives.fr. Archived from the original (ODS) on 2022-06-16. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- ^ Court of Audit (France) (November 2016). "Les Archives nationales - Les voies et moyens d'une nouvelle ambition" (PDF). p. 14. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ a b c "Accueil".

- ^ a b Atelier de Recherches sur les Textes Médiévaux (ARTEM), University of Lorraine (10 June 2010). "Chartes originales antérieures à 1121 conservées en France". Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Laurent Morelle. "Une royauté par éclats et lambeaux : les papyrus mérovingiens des Archives nationales" (PDF). École pratique des hautes études. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Henri Pirenne (June 1928). "Le commerce du papyrus dans la Gaule mérovingienne". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 72 (2): 178–191.

- ^ Archives nationales. "Cartons des rois - Inventaire des actes produits entre la fin du VIe siècle et 986". Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Archives nationales. "« Monuments historiques » - Titre I : Cartons des rois - Inventaire analytique de K 1 à 164". Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "Original Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789 1791)". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2009-02-27. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ a b c "Rapport d'activité 2011-2012". www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr. p. 16. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ a b Court of Audit (France) (November 2016). "Les Archives nationales - Les voies et moyens d'une nouvelle ambition" (PDF). p. 36. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "Chantiers d'inventaires du Minutier central des notaires de Paris". www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ a b "Livret de présentation du site" (PDF). Archives nationales. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ a b "Archives nationales - Site de Pierrefitte-sur-Seine". www.lejournaldesarts.fr. 2021. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ "Rapport d'activité 2020". www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr. p. 45. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ Françoise Banat-Berger (2019). "Les Archives nationales : une institution en profonde mutation". Histoire@Politique. 39 (39). Sciences Po: 144–162. doi:10.4000/histoirepolitique.3409.

Bibliography

- Favier, Lucie, 2004. La mémoire de l'État: histoire des Archives nationales. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-61758-9.

- Claire Béchu (dir.), Les Archives nationales, des lieux pour l'histoire de France: bicentenaire d'une installation (1808–2008), Paris, Somogy & Archives nationales, 2008, 384 p. (ISBN 978-2-7572-0187-9)

- Philippe Béchu & Christian Taillard, Les Hôtels de Soubise et de Rohan, Paris, Somogy, 2004, 488 p. (ISBN 2-85056-796-5)

- Miller, David C.(2019) "Armand-Gaston Camus: Catholic Scholar, Revolutionary, and Founder of the National Archives of France." Catholic Library World (December) 90, no.2