Guido of Arezzo

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

Guido of Arezzo (Italian: Guido d'Arezzo;[n 1] c. 991–992 – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a massive influence on the development of Western musical notation and practice.[1][2] Perhaps the most significant European writer on music between Boethius and Johannes Tinctoris,[3] after the former's De institutione musica, Guido's Micrologus was the most widely distributed medieval treatise on music.[4]

Biographical information on Guido is only available from two contemporary documents; though they give limited background, a basic understanding of his life can be unravelled. By around 1013 he began teaching at Pomposa Abbey, but his antiphonary Prologus in antiphonarium and novel teaching methods based on staff notation brought considerable resentment from his colleagues. He thus moved to Arezzo in 1025 and under the patronage of Bishop Tedald of Arezzo he taught singers at the Arezzo Cathedral. Using staff notation, he was able to teach large amounts of music quickly and he wrote the multifaceted Micrologus, attracting attention from around Italy. Interested in his innovations, Pope John XIX called him to Rome. After arriving and beginning to explain his methods to the clergy, sickness sent him away in the summer. The rest of his life is largely unknown, but he settled in a monastery near Arezzo, probably one of the Avellana of the Camaldolese order.

Context and sources

Information on Guido's life is scarce; the music historian Charles Burney asserted that the paucity of records was because Guido was a monk.[5] Burney furthered that, in the words of musicologist Samuel D. Miller, "Guido's modesty, selfless abandon from material gain life, and obedience to authority tended to obscure his moves, work, and motivations".[2] The scholarly outline of Guido's life has been subject to much mythologization and misunderstandings.[6] These dubious claims include that he spent much of life in France (recorded as early as Johannes Trithemius's 1494 De scriptoribus ecclesiasticis); that he trained in the Saint-Maur-des-Fossés near Paris;[6] and unsupported rumours that he was imprisoned because of plots from those hostile to his innovations.[2]

The primary surviving documents associated with Guido are two undated letters; a dedicatory letter to Bishop Tedald of Arezzo and a letter to his colleague Michael of Pomposa, known as the Epistola ad Michaelem.[7][n 2] These letters provide enough information and context to map of the main events and chronology of Guido's life,[7] though Miller notes that they do "not permit a detailed, authoritative sketch".[2]

Life and career

Early life

Guido was born sometime between 990 and 999.[7] This birthdate range was conjectured from a now lost and undated manuscript of the Micrologus, where he stated that he was age 34 while John XIX was pope (1024–1033).[7] Swiss musicologist Hans Oesch's dating of the manuscript to 1025–1026 is agreed by scholars Claude V. Palisca, Dolores Pesce and Angelo Mafucci, with Mafucci noting that it is "now unanimously accepted".[10][11][n 3] This would suggest a birthdate of c. 991–992.[10][n 4]

Guido's birthplace is even less certain, and has been the subject of much disagreement between scholars,[13] with music historian Cesarino Ruini noting that due to Guido's pivotal significance "It is understandable that several locations in Italy claim the honor of having given birth to G[uido]".[6][n 5] There are two principal candidates: Arezzo, Tuscany or the Pomposa Abbey on the Adriatic coast near Ferrara.[14][n 6] Musicologist Jos. Smits van Waesberghe asserted that he was born in Pomposa due to his strong connection with the Abbey from c. 1013–1025; according to Van Waesberghe, Guido's epitaph 'of Arezzo' is because of his stay of about a dozen years there later in life.[11] Disagreeing with Van Waesberghe's conclusions, Mafucci argued that were Guido born in Pomposa, he would have spent nearly 35 years there and would thus more likely be known as 'of Pomposa'.[11] Mafucci cites the account of the near-contemporary historian Sigebert of Gembloux (c. 1030–1112) who referred to Guido as "Guido Aretinus" (Guido of Arezzo), suggesting that the early use of such a designation means Guido's birthplace was Arezzo.[16] Citing recently unearthed documents in 2003, Mafucci identified Guido with a Guido clerico filius Roze of the Arezzo Cathedral.[17] If Mafucci is correct, Guido would have received early musical education at the Arezzo Cathedral from a deacon named Sigizo and was ordained as a subdeacon and active as a cantor.[18][n 7]

Pomposa

"Guido [...] perhaps attracted by the fame of what was considered one of the most famous Benedictine abbeys, full of hope of new spiritual and musical life, he enters the monastery of Pomposa, unaware of the storm that, in a few years, it would hit him. In fact [...] it will be his own brothers and the abbot himself who will force him to leave Pomposa."

Around 1013 Guido went to the Pomposa Abbey, one of the most famous Benedictine monasteries of the time, to complete his education.[19] Becoming a noted monk,[5] he started to develop the novel principles of staff notation (music being written and read from an organized visual system).[1]

Likely drawing from the writings of Odo of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés,[1] Guido began to draft his system in the antiphonary Regulae rhythmicae, which he probably worked on with his colleague Michael of Pomposa.[7][n 9] In the prologue to the antiphonary, Guido expressed his frustration with the large amount of time singers spent to memorize music.[21] The system, he explained, would prevent the need for memorization and thus permit the singers extra time to diversify their studies into other prayers and religious texts.[6] He began to instruct his singers along these lines and obtained a reputation for being able to teach substantial amounts of music quickly.[7] Though his ideas brought interest from around Italy, they inspired considerable jealousy and resistance from his fellow monks,[1][7] who felt threatened by his innovations.[6] Among those disapproving was the Abbot Guido of Pomposa.[6] In light of these objections, Guido left Pomposa in around 1025 and moved to—or 'returned to', if following the Arezzo birthplace hypothesis—Arezzo.[1]

Arezzo, Rome and later life

Arezzo was without a monastery; Bishop Tedald of Arezzo (Bishop from 1023 to 1036) appointed Guido to oversee the training of singers for the Arezzo Cathedral.[7] It was at this time that Guido began work on the Micrologus, or in full Micrologus de disciplina artis musicae.[1] The work was both commissioned by and dedicated to Tedald.[7] It was primarily a musical manual for singers and discussed a wide variety of topics, including chant, polyphonic music, the monochord, melody, syllables, modes, organum, neumes and many of his teaching methods.[22] Resuming the same teaching approach as before, Guido lessened the standard 10-year training for the ideal cantor to only one or two years.[6] Italy-wide attention returned to Guido, and Pope John XIX called him to Rome, having either seen or heard of both his Regulae rhythmicae and innovative staff notation teaching techniques.[7] Theobald may have helped arranged the visit,[1] and in around 1028, Guido traveled there with the Canon Dom Peter of Arezzo as well as the Abbot Grimaldus of Arezzo.[6][7][n 10] His presentation incited much interest from the clergy and the details of his visit are included in the Epistola ad Michaelem.[6]

While in Rome, Guido became sick and the hot summer forced him to leave, with the assurance that he would visit again and give further explanation of his theories.[7] In the Epistola ad Michaelem, Guido mentions that before leaving, he was approached by the Abbot Guido of Pomposa who regretted his part in Guido's leave from Arezzo and thus invited him to return to the Abbey.[6] Guido of Pomposa's rationale was that he should avoid the cities, as most of their churchmen were accused of simony,[7] though it remains unknown if Guido chose the Pomposa Abbey as his destination.[6] It seems more likely that around 1029,[1] Guido settled in a monastery of the Avellana of the Camaldolese order near Arezzo, as many of the oldest manuscripts with Guidonian notation are Camaldolese.[7] The last document pertaining to Guido places him in Arezzo on 20 May 1033;[6] his death is only known to have been sometime after that date.[7]

Music theory and innovations

Works

Works by Guido of Arezzo

- The Micrologus (c. 1025–1026)[n 4]

- Regulae rhythmicae (after 1026)

- Prologus in antiphonarium (c. 1030)[12]

- Epistola ad Michaelem (c. 1032)[12]

Four works are securely attributed to Guido:[23] the Micrologus, the Prologus in antiphonarium, the Regulae rhythmicae and the Epistola ad Michaelem.[7][n 2]

The Epistola ad Michaelem is the only one not a formal musical treatise; it was written directly after Guido's trip to Rome,[20] perhaps in 1028,[7] but no later than 1033.[20] All three musical treatises were written before the Epistola ad Michaelem, as Guido mentions each of them in it.[20] More specifically, the Micrologus can be dated to after 1026, as in the preliminary dedicatory letter to Tebald, Guido congratulates him for his 1026 plans for the new St Donatus church.[20] Though the Prologus in antiphonarium was begun in Pomposa (1013–1025), it seems to have not been completed until 1030.[20]

Solmization

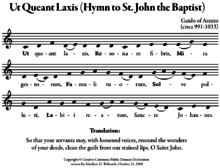

Guido developed new techniques for teaching, such as staff notation and the use of the "ut–re–mi–fa–sol–la" (do–re–mi–fa–so–la) mnemonic (solmization). The syllables ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la (do-re-mi-fa-sol-la) are taken from the six half-lines of the first stanza of the hymn Ut queant laxis, the notes of which are successively raised by one step, and the text of which is attributed to the Italian monk and scholar Paulus Deacon (although the musical line either shares a common ancestor with the earlier setting of Horace's Ode to Phyllis (Odes 4.11) recorded in Montpellier manuscript H425, or may have been taken from there)[24] Giovanni Battista Doni is known for having changed the name of note "Ut" (C), renaming it "Do" (in the "Do Re Mi ..." sequence known as solfège).[25] A seventh note, "Si" (from the initials for "Sancte Iohannes," Latin for Saint John the Baptist) was added shortly after to complete the diatonic scale.[26] In anglophone countries, "Si" was changed to "Ti" by Sarah Glover in the nineteenth century so that every syllable might begin with a different letter (this also freed up Si for later use as Sol-sharp). "Ti" is used in tonic sol-fa and in the song "Do-Re-Mi".

The Guidonian hand

Guido is somewhat erroneously credited with the invention of the Guidonian hand,[10][27][vague] a widely used mnemonic system where note names are mapped to parts of the human hand. Only a rudimentary form of the Guidonian hand is actually described by Guido, and the fully elaborated system of natural, hard, and soft hexachords cannot be securely attributed to him.[28]

In the 12th century, a development in teaching and learning music in a more efficient manner arose. Guido of Arezzo's alleged development of the Guidonian hand, more than a hundred years after his death, allowed musicians to label a specific joint or fingertip with the gamut (also referred to as the hexachord in the modern era).[citation needed] Using specific joints of the hand and fingertips transformed the way one would learn and memorize solmization syllables. Not only did the Guidonian hand become a standard use in preparing music in the 12th century, its popularity grew more widespread well into the 17th and 18th centuries.[29] The knowledge and use of the Guidonian hand would allow a musician to simply transpose, identify intervals, and aid in the use of notation and the creation of new music. Musicians were able to sing and memorize longer sections of music and counterpoint during performances and the amount of time spent diminished dramatically.[30]

Legacy

Almost immediately after his death commentaries were written on Guido's work, particularly the Micrologus.[31] One of the most noted is the De musica of Johannes Cotto (fl. c. 1100), whose influential treatise was largely a commentary that expanded and revised the Micrologus.[32] Aribo (fl. c. 1068–78) also dedicated a substantial part of his De musica as a commentary on chapter 15 of the Micrologus.[33] Other significant commentaries are anonymous, including the Liber argumentorum and Liber specierum (both Italian, 1050–1100); the Commentarius anonymus in Micrologum (Belgian or Bavarian, c. 1070–1100); and the Metrologus (English, 13th century).[31]

Guido of Arezzo and his work are frequent namesakes. The controversial mass Missa Scala Aretina (1702) by Francisco Valls takes its name from Guido's hexachord.[34] Lorenzo Nencini sculpted a statue of Guido in 1847 that is included in the Loggiato of the Uffizi, Florence.[35] A statue to him was erected 1882 in his native Arezzo; it was sculpted by Salvino Salvini.[36] Modern namesakes include the computer music notation system GUIDO music notation,[37] as well as the "Concorso Polifónico Guido d'Arezzo" (International Guido d'Arezzo Polyphonic Contest) hosted by the Fondazione Guido D'Arezzo in Arezzo.[38] A street in Milan, Via Guido D'Arezzo, is named after him.[39]

In 1950, the Comitato Nazionale per le Onoranze a Guido Monaco (National Committee for Honors to Guido Monaco) held various events for the ninth centenary of Guido's death. Among these was a monograph competition; Jos Smits van Waesberghe won with the Latin work De musico-paedagogico et theoretico Guidone Aretino eiusque vita et moribus (The Musical-Pedagogy of Theoretician Guido of Arezzo Both His Life and Morals).[11]

Editions

- Guido of Arezzo (1955). van Waesberghe, Jos Smits [in Dutch] (ed.). Micrologus. Corpus Scriptorum de Musica. Vol. 4. Rome: American Institute of Musicology. OCLC 1229808694.

- —— (1975). van Waesberghe, Jos Smits [in Dutch] (ed.). Prologus in antiphonarium. Divitiae Musicae Artis. Buren: Frits Knuf. OCLC 251805291.

- —— (1978). "Micrologus". In Palisca, Claude V. (ed.). Hucbald, Guido, and John on music: Three Medieval Treatises. Translated by Babb, Warren. Index of chants by Alejandro Enrique Planchart. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02040-3.

- —— (1985). van Waesberghe, Jos Smits [in Dutch]; Vetter, Eduard (eds.). Regulae rhythmicae. Divitiae Musicae Artis. Buren: Frits Knuf. OCLC 906533025.

- —— (1993). Micrologus (in French). Translated by Colette, Marie-Noël; Jolivet, Jean-Christophe. Paris: Édition IPMC. ISBN 978-2-906460-28-7. OCLC 935613218.

- —— (1999). Guido d'Arezzo's Regule rithmice, Prologus in antiphonarium, and Epistola ad michahelem: a critical text and translation, with an introduction, annotations, indices, and new manuscript inventories. Translated by Pesce, Dolores. Ottawa: Institute of Mediaeval Music. ISBN 978-1-896926-18-6. OCLC 247329370.

References

Notes

- ^ Guido's name is recorded in many variants, including Guido Aretinus, Guido Aretino, Guido da Arezzo, Guido Monaco, Guido d'Arezzo, Guido Monaco Pomposiano, or Guy of Arezzo also Guy d'Arezzo

- ^ a b The Epistola ad Michaelem is also known as the Epistola de ignoto cantu or the Epistola de cantu ignoto.[8][9]

- ^ Translated as "now unanimously accepted" from the original Italian: "ormai unanimemente accettata".[11]

- ^ a b Other musicologists have concluded different datings for the Micrologus. Jos. Smits van Waesberghe had dated the work to 1028–1032, suggesting a birthdate of 994–998,[7] while Charles Atkinson dated it to c. 1026–1028, suggesting a birthdate of 992–994.[12]

- ^ Translated as "It is understandable that several locations in Italy claim the honor of having given birth to G[uido]" from the original Italian: "È comprensibile che diverse località in Italia rivendichino l'onore di avere dato i natali a G[uido]".[6]

- ^ Older commentators have proposed revisionist theories that he originated from England or Germany.[6] Mafucci noted that theories other than Arezzo and Pomposa are too baseless to be considered.[15]

- ^ Palisca (2001a) does not include Mafucci's conclusions; however, it is worth noting that Palisca's Grove article was written before the publication of Mafucci (2003).

- ^ Translated as "Guido [...] perhaps attracted by the fame of what was considered one of the most famous Benedictine abbeys, full of hope of new spiritual and musical life, he enters the monastery of Pomposa, unaware of the storm that, in a few years, it would hit him. In fact [...] it will be his own brothers and the abbot himself who will force him to leave Pomposa." from the original Italian: "Guido [...] forse attratto dalla fama di quella che era considerata una delle più celebri abbazie benedettine, pieno di speranza di nuova vita spirituale e musicale, entra nel monastero di Pomposa, ignaro tuttavia della bufera che, di lì a qualche anno, si sarebbe abbattuta su di lui. Se infatti [...] da Pomposa saranno i suoi stessi confratelli e lo stesso abate che lo costringeranno alla partenza."[19]

- ^ In his letter to Michael, Epistola ad Michaelem, Guido referred to the Prologus in antiphonarium as "nostrum antiphonarium" ("our antiphoner") suggesting they had drafted it together.[20] This remains uncheckable as the work is now lost.[21]

- ^ Dom Peter of Arezzo was the Prefect of the Canons at the Arezzo Cathedral.[6][7] Abbot Grimaldus of Arezzo's identity is uncertain; Ruini (2004) suggested that he was "an unknown Grünwald of Germanic origin", while Palisca (2001a, "1. Life") suggested he was an Abbot of Badicroce, which was about 15 kilometers south of Arezzo.

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h Britannica 2021.

- ^ a b c d Miller 1973, p. 239.

- ^ Grier 2018, "Introduction".

- ^ Haines 2008, p. 328.

- ^ a b Miller 1973, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ruini 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Palisca 2001a, "1. Life".

- ^ "Harley MS 3199". The British Library. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Palisca 2001a, "Writings".

- ^ a b c Palisca 2001a, "Introduction".

- ^ a b c d e Mafucci 2003, "Il Parere Di J. Smits Van Waesberghe" ["The Opinion of J. Smits Van Waesberghe"].

- ^ a b c Atkinson 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Introduction", "Il Parere Di J. Smits Van Waesberghe" ["The Opinion of J. Smits Van Waesberghe"].

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Introduction".

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Note 2".

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Nascita Aretina Di Guido Monaco" ["Aretina Birth of Guido Monaco"].

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Guido Entra Alla Scuola Dei Chierici" ["Guido Enters the School of the Clerks"].

- ^ Mafucci 2003, "Guido Entra Alla Scuola Dei Chierici" ["Guido Enters the School of the Clerks"], "Guido Lascia Arezzo per Pomposa" ["Guido Leaves Arezzo for Pomposa"].

- ^ a b c Mafucci 2003, "Guido Lascia Arezzo per Pomposa" ["Guido Leaves Arezzo for Pomposa"].

- ^ a b c d e f Palisca 2001a, "2. Writings": "(i) Chronology".

- ^ a b Palisca 2001a, "2. Writings": "(ii) Prologus in antiphonarium".

- ^ Palisca 2001a, "2. Writings": "(iii) Micrologus".

- ^ Herlinger 2004, p. 471.

- ^ Stuart Lyons, Horace's Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi with Full Verse Translation of the Odes. Oxford: Aris & Phillips, 2007. ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7

- ^ McNaught, W. G. (1893). "The History and Uses of the Sol-fa Syllables". Proceedings of the Musical Association. 19. London: Novello, Ewer and Co.: 35–51. doi:10.1093/jrma/19.1.35. ISSN 0958-8442. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 271–7). ISBN 978-0-19-520912-9; ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

- ^ "Solmization" by Andrew Hughes and Edith Gerson-Kiwi, Grove Music Online (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Claude V. Palisca, "Theory, Theorists, §5: Early Middle Ages", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers).

- ^ Bonnie J. Blackburn, "Lusitano, Vicente", Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. accessed 13 July 2016.

- ^ Don Michael Randel, "Guido of Arezzo", The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996): 339–40.

- ^ a b Palisca 2001a, "2. Writings": "(vi) Commentaries".

- ^ Palisca 2001b, "2. The treatise".

- ^ Hughes 2001.

- ^ Fitch, Fabrice. "VALLS Missa Scala Aretina". Gramophone. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Firenze – Statue degli illustri nel loggiato degli Uffizi". Statues – Hither & Thither. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Arezzo – Guido Monaco". Statues – Hither & Thither. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Guido Music Notation". Grame-CNCM. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "The Foundation". Fondazione Guido D'Arezzo. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "Via Guido D'Arezzo". Google Maps. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

Sources

- Books

- Atkinson, Charles M. (2008). The Critical Nexus: Tone-System, Mode, and Notation in Early Medieval Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972238-9.

- Journal and encyclopedia articles

- Grier, James (2018). "Guido of Arezzo". Oxford Bibliographies: Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199757824-0248. (subscription required)

- Haines, John (2008). "The Origins of the Musical Staff". The Musical Quarterly. 91 (3/4). Oxford University Press: 327–378. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdp002. JSTOR 20534535.

- Herlinger, Jan (2004). "Guido d'Arezzo". In Kleinhenz, Christopher (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis.

- Hughes, Andrew (2001). "Aribo". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.01233. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Mafucci, Angelo (2003). "Guido d'Arezzo: I primi venti anni della sua vita" [Guido d'Arezzo: The First Twenty Years of His Life]. Rivista Internationale di Musica Sacra (in Italian). 24 (2): 111–122. Reprinted on musicologie.org.

- Miller, Samuel D. (Autumn 1973). "Guido d'Arezzo: Medieval Musician and Educator". Journal of Research in Music Education. 21 (3): 239–245. doi:10.2307/3345093. JSTOR 3345093. S2CID 143833782.

- Palisca, Claude V. (2001a). "Guido of Arezzo". Grove Music Online. Revised by Dolores Pesce. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11968. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 19 September 2020. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Palisca, Claude (2001b). "Johannes Cotto". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14349. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Ruini, Cesarino (2004). "Guido d'Arezzo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 64. Treccani.

- "Guido d'Arezzo | Italian musician | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1 January 2021. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020.

Further reading

See Grier (2018) for an extensive bibliography

- Books

- Hoppin, Richard (1978). Medieval Music. The Norton Introduction to Music History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-09090-1.

- Lyons, Stuart (2010). Music in the Odes of Horace. Oxford: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-844-7.

- Mengozzi, Stefano (2010). The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo Between Myth and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88415-0.

- Oesch, Hans [in German] (1978). Guido von Arezzo: Biographisches und Theoretisches unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der sogenannten odonischen Traktate [Guido von Arezzo: Biographical and theoretical matters with special consideration of the so-called odonic treatises]. Publikationen der Schweizerischen Musikforschenden Gesellschaft (in German). Bern: P. Haupt. OCLC 527452.

- Pesce, Dolores (2010). "Guido d'Arezzo, Ut queant laxis, and Musical Understanding". In Murray, Russell E.; Weiss, Susan Forscher; Cyrus, Cynthia J. (eds.). Music Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 25–36. ISBN 978-0-253-00455-0.

- Journal and encyclopedia articles

- Berger, Carol (1981). "The Hand and the Art of Memory". Musica Disciplina. 35. American Institute of Musicology Verlag Corpusmusicae, GmbH: 87–120. JSTOR 20532236.

- Carey, Norman; Clampitt, David (Spring 1996). "Regions: A Theory of Tonal Spaces in Early Medieval Treatises". Journal of Music Theory. 40 (1). Duke University Press: 113–147. JSTOR 843924.

- Fuller, Sarah (January–June 1981). "Theoretical Foundations of Early Organum Theory". Acta Musicologica. 53 (Fasc. 1). International Musicological Society: 52–84. doi:10.2307/932569. JSTOR 932569.

- Green, Edward (December 2007). "What Is Chapter 17 of Guido's 'Micrologus' about? A Proposal for a New Answer". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. 38 (2): 143–170. JSTOR 25487523.

- Huglo, Michel (1988). "Bibliographie des éditions et études relatives à la théorie musicale du Moyen Âge (1972–1987)" [Bibliography of Editions and Studies Relating to Medieval Music Theory (1972–1987)]. Acta Musicologica. 60 (Fasc. 3). Basel: International Musicological Society: 229–272 [252]. doi:10.2307/932753. JSTOR 932753.

- Mengozzi, Stefano (Summer 2006). "Virtual Segments: The Hexachordal System in the Late Middle Ages". The Journal of Musicology. 23 (3). University of California Press: 426–467. doi:10.1525/jm.2006.23.3.426. JSTOR 10.1525/jm.2006.23.3.426.

- Reisenweaver, Anna J. (2012). "Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning". Musical Offerings. 3 (1): 55–63. doi:10.15385/jmo.2012.3.1.4.

- Russell, Tilden A. (Spring 1981). "A Poetic Key to a Pre-Guidonian Palm and the 'Echemata'". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 34 (1). University of California Press: 109–118. doi:10.2307/831036. JSTOR 831036.

- Sullivan, Blair (1989). "Interpretive Models of Guido of Arezzo's Micrologus" (PDF). Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 20 (1): 20–42.

- van Waesberghe, Jos Smits [in Dutch] (1951). "The Musical Notation of Guido of Arezzo". Musica Disciplina. 5. American Institute of Musicology Verlag Corpusmusicae, GmbH: 15–53. JSTOR 20531824.

- van Waesberghe, Jos Smits [in Dutch] (1951). "Guido of Arezzo and Musical Improvisation". Musica Disciplina. 5. American Institute of Musicology Verlag Corpusmusicae, GmbH: 55–63. JSTOR 20531825.

External links

- Free scores by Guido of Arezzo at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- List of compositions by Guido of Arezzo at the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music

- Manuscripts of works by Guido at The British Library

- Transcription of the Micrologus in Latin on the Thesaurus Musicarum Latinarum of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music