Greek alphabet

| Greek alphabet | |

|---|---|

Ellinikó alfávito "Greek alphabet" in the modern Greek language | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 800 BC – present[1] |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Official script | |

| Languages | Greek |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Grek (200), Greek |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Greek |

| |

| Greek alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diacritics and other symbols | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BC.[2][3] It was derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet,[4] and is the earliest known alphabetic script to have developed distinct letters for consonants as well as vowels.[5] In Archaic and early Classical times, the Greek alphabet existed in many local variants, but, by the end of the 4th century BC, the Ionic-based Euclidean alphabet, with 24 letters, ordered from alpha to omega, had become standard throughout the Greek-speaking world[6] and is the version that is still used for Greek writing today.[7]

The uppercase and lowercase forms of the 24 letters are:

- Α α, Β β, Γ γ, Δ δ, Ε ε, Ζ ζ, Η η, Θ θ, Ι ι, Κ κ, Λ λ, Μ μ, Ν ν, Ξ ξ, Ο ο, Π π, Ρ ρ, Σ σ (word-final form: ς), Τ τ, Υ υ, Φ φ, Χ χ, Ψ ψ, Ω ω.

The Greek alphabet is the ancestor of several scripts, such as the Latin, Gothic, Coptic, and Cyrillic scripts.[8] Throughout antiquity, Greek had only a single uppercase form of each letter. It was written without diacritics and with little punctuation.[9] By the 9th century, Byzantine scribes had begun to employ the lowercase form, which they derived from the cursive styles of the uppercase letters.[10] Sound values and conventional transcriptions for some of the letters differ between Ancient and Modern Greek usage because the pronunciation of Greek has changed significantly between the 5th century BC and today. Additionally, Modern and Ancient Greek now use different diacritics, with ancient Greek using the polytonic orthography and modern Greek keeping only the stress accent (acute) and the diaeresis.

Apart from its use in writing the Greek language, in both its ancient and its modern forms, the Greek alphabet today also serves as a source of international technical symbols and labels in many domains of mathematics, science, and other fields.

Letters

Sound values

In both Ancient and Modern Greek, the letters of the Greek alphabet have fairly stable and consistent symbol-to-sound mappings, making pronunciation of words largely predictable. Ancient Greek spelling was generally near-phonemic. For a number of letters, sound values differ considerably between Ancient and Modern Greek, because their pronunciation has followed a set of systematic phonological shifts that affected the language in its post-classical stages.[11]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Examples

- Notes

- ^ By around 350 BC, zeta in the Attic dialect had shifted to become a single fricative, [z], as in modern Greek.[21]

- ^ a b c The letters theta ⟨θ⟩, phi ⟨φ⟩, and chi ⟨χ⟩ are normally taught to English speakers with their modern Greek pronunciations of [θ], [f], and [x] ~ [ç] respectively, because these sounds are easier for English speakers to distinguish from the sounds made by the letters tau ([t]), pi ([p]), and kappa ([k]) respectively.[23][20] These are not the sounds they made in classical Attic Greek.[23][20] In classical Attic Greek, these three letters were always aspirated consonants, pronounced exactly like tau, pi, and kappa respectively, only with a blast of air following the actual consonant sound.[23][20]

- ^ The letter Λ is almost universally known today as lambda (λάμβδα) except in Modern Greek and in Unicode, where it is lamda (λάμδα), and the most common name for it during the Greek Classical Period (510–323 BC) appears to have been labda (λάβδα), without the μ.[15]

- ^ The letter sigma ⟨Σ⟩ has two different lowercase forms in its standard variant, with ⟨ς⟩ being used in word-final position and ⟨σ⟩ elsewhere.[20][24][25] In some 19th-century typesetting, ⟨ς⟩ was also used word-medially at the end of a compound morpheme, e.g. "δυςκατανοήτων", marking the morpheme boundary between "δυς-κατανοήτων" ("difficult to understand"); modern standard practice is to spell "δυσκατανοήτων" with a non-final sigma.[25]

- ^ The letter omega ⟨ω⟩ is normally taught to English speakers as [oʊ], the long o as in English go, in order to more clearly distinguish it from omicron ⟨ο⟩.[26][20] This is not the sound it actually made in classical Attic Greek.[26][20]

Among consonant letters, all letters that denoted voiced plosive consonants (/b, d, g/) and aspirated plosives (/pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/) in Ancient Greek stand for corresponding fricative sounds in Modern Greek. The correspondences are as follows:

| Former voiced plosives | Former aspirates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | Ancient | Modern | Letter | Ancient | Modern | |

| Labial | Β β | /b/ | /v/ | Φ φ | /pʰ/ | /f/ |

| Dental | Δ δ | /d/ | /ð/ | Θ θ | /tʰ/ | /θ/ |

| Dorsal | Γ γ | /ɡ/ | [ɣ] ~ [ʝ] | Χ χ | /kʰ/ | [x] ~ [ç] |

Among the vowel symbols, Modern Greek sound values reflect the radical simplification of the vowel system of post-classical Greek, merging multiple formerly distinct vowel phonemes into a much smaller number. This leads to several groups of vowel letters denoting identical sounds today. Modern Greek orthography remains true to the historical spellings in most of these cases. As a consequence, the spellings of words in Modern Greek are often not predictable from the pronunciation alone, while the reverse mapping, from spelling to pronunciation, is usually regular and predictable.

The following vowel letters and digraphs are involved in the mergers:

| Letter | Ancient | Modern |

|---|---|---|

| Η η | ɛː | > i |

| Ι ι | i(ː) | |

| ΕΙ ει | eː | |

| Υ υ | u(ː) > y | |

| ΟΙ οι | oi > y | |

| ΥΙ υι | yː > y | |

| Ω ω | ɔː | > o |

| Ο ο | o | |

| Ε ε | e | > e |

| ΑΙ αι | ai |

Modern Greek speakers typically use the same, modern symbol–sound mappings in reading Greek of all historical stages. In other countries, students of Ancient Greek may use a variety of conventional approximations of the historical sound system in pronouncing Ancient Greek.

Digraphs and letter combinations

Several letter combinations have special conventional sound values different from those of their single components. Among them are several digraphs of vowel letters that formerly represented diphthongs but are now monophthongized. In addition to the four mentioned above (⟨ει, οι, υι⟩, pronounced /i/ and ⟨αι⟩, pronounced /e/), there is also ⟨ηι, ωι⟩, and ⟨ου⟩, pronounced /u/. The Ancient Greek diphthongs ⟨αυ⟩, ⟨ευ⟩ and ⟨ηυ⟩ are pronounced [av], [ev] and [iv] in Modern Greek. In some environments, they are devoiced to [af], [ef] and [if].[27] The Modern Greek consonant combinations ⟨μπ⟩ and ⟨ντ⟩ stand for [b] and [d] (or [mb] and [nd]); ⟨τζ⟩ stands for [d͡z] and ⟨τσ⟩ stands for [t͡s]. In addition, both in Ancient and Modern Greek, the letter ⟨γ⟩, before another velar consonant, stands for the velar nasal [ŋ]; thus ⟨γγ⟩ and ⟨γκ⟩ are pronounced like English ⟨ng⟩ like in the word finger (not like in the word thing). In analogy to ⟨μπ⟩ and ⟨ντ⟩, ⟨γκ⟩ is also used to stand for [g] before vowels [a], [o] and [u], and [ɟ] before [e] and [i]. There are also the combinations ⟨γχ⟩ and ⟨γξ⟩.

| Combination | Pronunciation | Devoiced pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨ου⟩ | [u] | – |

| ⟨αυ⟩ | [av] | [af] |

| ⟨ευ⟩ | [ev] | [ef] |

| ⟨ηυ⟩ | [iv] | [if] |

| ⟨μπ⟩ | [b] or [mb] | – |

| ⟨ντ⟩ | [d] or [nd] | – |

| ⟨γκ⟩ and ⟨γγ⟩ | [ɡ], [ɟ] or [ŋɡ], [ŋɟ] | – |

| ⟨τζ⟩ | [d͡z] | – |

| ⟨τσ⟩ | [t͡s] | – |

| ⟨γ⟩ in ⟨γχ⟩ and ⟨γξ⟩ | [ŋ] | – |

Diacritics

In the polytonic orthography traditionally used for ancient Greek and katharevousa, the stressed vowel of each word carries one of three accent marks: either the acute accent (ά), the grave accent (ὰ), or the circumflex accent (α̃ or α̑). These signs were originally designed to mark different forms of the phonological pitch accent in Ancient Greek. By the time their use became conventional and obligatory in Greek writing, in late antiquity, pitch accent was evolving into a single stress accent, and thus the three signs have not corresponded to a phonological distinction in actual speech ever since. In addition to the accent marks, every word-initial vowel must carry either of two so-called "breathing marks": the rough breathing (ἁ), marking an /h/ sound at the beginning of a word, or the smooth breathing (ἀ), marking its absence. The letter rho (ρ), although not a vowel, also carries rough breathing in a word-initial position. If a rho was geminated within a word, the first ρ always had the smooth breathing and the second the rough breathing (ῤῥ) leading to the transliteration rrh.

The vowel letters ⟨α, η, ω⟩ carry an additional diacritic in certain words, the so-called iota subscript, which has the shape of a small vertical stroke or a miniature ⟨ι⟩ below the letter. This iota represents the former offglide of what were originally long diphthongs, ⟨ᾱι, ηι, ωι⟩ (i.e. /aːi, ɛːi, ɔːi/), which became monophthongized during antiquity.

Another diacritic used in Greek is the diaeresis (¨), indicating a hiatus.

This system of diacritics was first developed by the scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium (c. 257 – c. 185/180 BC), who worked at the Musaeum in Alexandria during the third century BC.[28] Aristophanes of Byzantium also was the first to divide poems into lines, rather than writing them like prose, and also introduced a series of signs for textual criticism.[29] In 1982, a new, simplified orthography, known as "monotonic", was adopted for official use in Modern Greek by the Greek state. It uses only a single accent mark, the acute (also known in this context as tonos, i.e. simply "accent"), marking the stressed syllable of polysyllabic words, and occasionally the diaeresis to distinguish diphthongal from digraph readings in pairs of vowel letters, making this monotonic system very similar to the accent mark system used in Spanish. The polytonic system is still conventionally used for writing Ancient Greek, while in some book printing and generally in the usage of conservative writers it can still also be found in use for Modern Greek.

Although it is not a diacritic, the comma has a similar function as a silent letter in a handful of Greek words, principally distinguishing ό,τι (ó,ti, "whatever") from ότι (óti, "that").[30]

Romanization

There are many different methods of rendering Greek text or Greek names in the Latin script.[31] The form in which classical Greek names are conventionally rendered in English goes back to the way Greek loanwords were incorporated into Latin in antiquity.[32] In this system, ⟨κ⟩ is replaced with ⟨c⟩, the diphthongs ⟨αι⟩ and ⟨οι⟩ are rendered as ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩ (or ⟨æ,œ⟩); and ⟨ει⟩ and ⟨ου⟩ are simplified to ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩.[33] Smooth breathing marks are usually ignored and rough breathing marks are usually rendered as the letter ⟨h⟩.[34] In modern scholarly transliteration of Ancient Greek, ⟨κ⟩ will usually be rendered as ⟨k⟩, and the vowel combinations ⟨αι, οι, ει, ου⟩ as ⟨ai, oi, ei, ou⟩.[31] The letters ⟨θ⟩ and ⟨φ⟩ are generally rendered as ⟨th⟩ and ⟨ph⟩; ⟨χ⟩ as either ⟨ch⟩ or ⟨kh⟩; and word-initial ⟨ρ⟩ as ⟨rh⟩.[35]

Transcription conventions for Modern Greek[36] differ widely, depending on their purpose, on how close they stay to the conventional letter correspondences of Ancient Greek-based transcription systems, and to what degree they attempt either an exact letter-by-letter transliteration or rather a phonetically based transcription.[36] Standardized formal transcription systems have been defined by the International Organization for Standardization (as ISO 843),[36][37] by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names,[38] by the Library of Congress,[39] and others.

| Letter | Traditional Latin transliteration[35] |

|---|---|

| Α α | A a |

| Β β | B b |

| Γ γ | G g |

| Δ δ | D d |

| Ε ε | E e |

| Ζ ζ | Z z |

| Η η | Ē ē |

| Θ θ | Th th |

| Ι ι | I i |

| Κ κ | C c, K k |

| Λ λ | L l |

| Μ μ | M m |

| Ν ν | N n |

| Ξ ξ | X x |

| Ο ο | O o |

| Π π | P p |

| Ρ ρ | R r, Rh rh |

| Σ σ/ς | S s |

| Τ τ | T t |

| Υ υ | Y y, U u |

| Φ φ | Ph ph |

| Χ χ | Ch ch, Kh kh |

| Ψ ψ | Ps ps |

| Ω ω | Ō ō |

History

Origins

During the Mycenaean period, from around the sixteenth century to the twelfth century BC, a script called Linear B was used to write the earliest attested form of the Greek language, known as Mycenaean Greek. This writing system, unrelated to the Greek alphabet, last appeared in the thirteenth century BC.[7] Inscription written in the Greek alphabet begin to emerge from the eighth century BC onward. While early samples of the Greek alphabet date from at least 775 BC,[40] the oldest known substantial and comprehensible Greek inscriptions, such as those on the Dipylon vase, the cup of Nestor and Acesander, date from c. 740/30 BC.[41] It is accepted that the introduction of the alphabet occurred some time prior to these inscriptions.[note 1] While earlier dates have been proposed,[42] the Greek alphabet is commonly held to have originated some time in the late ninth[43] or early eighth century BC,[44] conventionally around the year 800 BC.[1]

The period between the use of the two writing systems, Linear B and the Greek alphabet, during which no Greek texts are attested, is known as the Greek Dark Ages.[45] The Greeks adopted the alphabet from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, one of the closely related scripts used for the West Semitic languages, calling it Greek: Φοινικήια γράμματα 'Phoenician letters'.[46] However, the Phoenician alphabet was limited to consonants. When it was adopted for writing Greek, certain consonants were adapted in order to express vowels. The use of both vowels and consonants makes Greek the first alphabet in the narrow sense,[47] as distinguished from the abjads used in Semitic languages, which have letters only for consonants.[48]

Greek initially took over all of the 22 letters of Phoenician. Five were reassigned to denote vowel sounds: the glide consonants /j/ (yodh) and /w/ (waw) were used for [i] (Ι, iota) and [u] (Υ, upsilon); the glottal stop consonant /ʔ/ (aleph) was used for [a] (Α, alpha); the pharyngeal /ʕ/ (ʿayin) was turned into [o] (Ο, omicron); and the letter for /h/ (he) was turned into [e] (Ε, epsilon). A doublet of waw was also borrowed as a consonant for [w] (Ϝ, digamma). In addition, the Phoenician letter for the emphatic glottal /ħ/ (heth) was borrowed in two different functions by different dialects of Greek: as a letter for /h/ (Η, heta) by those dialects that had such a sound, and as an additional vowel letter for the long /ɛː/ (Η, eta) by those dialects that lacked the consonant. Eventually, a seventh vowel letter for the long /ɔː/ (Ω, omega) was introduced. Greek also introduced three new consonant letters for its aspirated plosive sounds and consonant clusters: Φ (phi) for /pʰ/, Χ (chi) for /kʰ/ and Ψ (psi) for /ps/. In western Greek variants, Χ was instead used for /ks/ and Ψ for /kʰ/. The origin of these letters is a matter of some debate.

| Phoenician | Greek | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aleph | /ʔ/ | Α | alpha | /a/, /aː/ | ||

| beth | /b/ | Β | beta | /b/ | ||

| gimel | /ɡ/ | Γ | gamma | /ɡ/ | ||

| daleth | /d/ | Δ | delta | /d/ | ||

| he | /h/ | Ε | epsilon | /e/, /eː/[note 2] | ||

| waw | /w/ | Ϝ | (digamma) | /w/ | ||

| zayin | /z/ | Ζ | zeta | [zd](?) | ||

| heth | /ħ/ | Η | eta | /h/, /ɛː/ | ||

| teth | /tˤ/ | Θ | theta | /tʰ/ | ||

| yodh | /j/ | Ι | iota | /i/, /iː/ | ||

| kaph | /k/ | Κ | kappa | /k/ | ||

| lamedh | /l/ | Λ | lambda | /l/ | ||

| mem | /m/ | Μ | mu | /m/ | ||

| nun | /n/ | Ν | nu | /n/ | ||

| Phoenician | Greek | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samekh | /s/ | Ξ | xi | /ks/ | ||

| ʿayin | /ʕ/ | Ο | omicron | /o/, /oː/[note 2] | ||

| pe | /p/ | Π | pi | /p/ | ||

| ṣade | /sˤ/ | Ϻ | (san) | /s/ | ||

| qoph | /q/ | Ϙ | (koppa) | /k/ | ||

| reš | /r/ | Ρ | rho | /r/ | ||

| šin | /ʃ/ | Σ | sigma | /s/ | ||

| taw | /t/ | Τ | tau | /t/ | ||

| (waw) | /w/ | Υ | upsilon | /u/, /uː/ | ||

| – | Φ | phi | /pʰ/ | |||

| – | Χ | chi | /kʰ/ | |||

| – | Ψ | psi | /ps/ | |||

| – | Ω | omega | /ɔː/ | |||

Three of the original Phoenician letters dropped out of use before the alphabet took its classical shape: the letter Ϻ (san), which had been in competition with Σ (sigma) denoting the same phoneme /s/; the letter Ϙ (qoppa), which was redundant with Κ (kappa) for /k/, and Ϝ (digamma), whose sound value /w/ dropped out of the spoken language before or during the classical period.

Greek was originally written predominantly from right to left, just like Phoenician, but scribes could freely alternate between directions. For a time, a writing style with alternating right-to-left and left-to-right lines (called boustrophedon, literally "ox-turning", after the manner of an ox ploughing a field) was common, until in the classical period the left-to-right writing direction became the norm. Individual letter shapes were mirrored depending on the writing direction of the current line.

Archaic variants

There were initially numerous local (epichoric) variants of the Greek alphabet, which differed in the use and non-use of the additional vowel and consonant symbols and several other features. Epichoric alphabets are commonly divided into four major types according to their different treatments of additional consonant letters for the aspirated consonants (/pʰ, kʰ/) and consonant clusters (/ks, ps/) of Greek.[49] These four types are often conventionally labelled as "green", "red", "light blue" and "dark blue" types, based on a colour-coded map in a seminal 19th-century work on the topic, Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Alphabets by Adolf Kirchhoff (1867).[49]

The "green" (or southern) type is the most archaic and closest to the Phoenician.[50] The "red" (or western) type is the one that was later transmitted to the West and became the ancestor of the Latin alphabet, and bears some crucial features characteristic of that later development.[50] The "blue" (or eastern) type is the one from which the later standard Greek alphabet emerged.[50] Athens used a local form of the "light blue" alphabet type until the end of the fifth century BC, which lacked the letters Ξ and Ψ as well as the vowel symbols Η and Ω.[50][51] In the Old Attic alphabet, ΧΣ stood for /ks/ and ΦΣ for /ps/. Ε was used for all three sounds /e, eː, ɛː/ (correspondinɡ to classical Ε, ΕΙ, Η), and Ο was used for all of /o, oː, ɔː/ (corresponding to classical Ο, ΟΥ, Ω).[51] The letter Η (heta) was used for the consonant /h/.[51] Some variant local letter forms were also characteristic of Athenian writing, some of which were shared with the neighboring (but otherwise "red") alphabet of Euboia: a form of Λ that resembled a Latin L (![]() ) and a form of Σ that resembled a Latin S (

) and a form of Σ that resembled a Latin S (![]() ).[51]

).[51]

| Phoenician model | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern | "green" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western | "red" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern | "light blue" | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "dark blue" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Classic Ionian | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Modern alphabet | Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | — | Ζ | — | Η | Θ | Ι | Κ | Λ | Μ | Ν | Ξ | Ο | Π | — | — | Ρ | Σ | Τ | Υ | — | Φ | Χ | Ψ | Ω | |

| Sound in Ancient Greek | a | b | g | d | e | w | zd | h | ē | tʰ | i | k | l | m | n | ks | o | p | s | k | r | s | t | u | ks | pʰ | kʰ | ps | ō | |

*Upsilon is also derived from waw (![]() ).

).

The classical twenty-four-letter alphabet that is now used to represent the Greek language was originally the local alphabet of Ionia.[52] By the late fifth century BC, it was commonly used by many Athenians.[52] In c. 403 BC, at the suggestion of the archon Eucleides, the Athenian Assembly formally abandoned the Old Attic alphabet and adopted the Ionian alphabet as part of the democratic reforms after the overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants.[52][53] Because of Eucleides's role in suggesting the idea to adopt the Ionian alphabet, the standard twenty-four-letter Greek alphabet is sometimes known as the "Eucleidean alphabet".[52] Roughly thirty years later, the Eucleidean alphabet was adopted in Boeotia and it may have been adopted a few years previously in Macedonia.[54] By the end of the fourth century BC, it had displaced local alphabets across the Greek-speaking world to become the standard form of the Greek alphabet.[54]

Letter names

When the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, they took over not only the letter shapes and sound values but also the names by which the sequence of the alphabet could be recited and memorized. In Phoenician, each letter name was a word that began with the sound represented by that letter; thus ʾaleph, the word for "ox", was used as the name for the glottal stop /ʔ/, bet, or "house", for the /b/ sound, and so on. When the letters were adopted by the Greeks, most of the Phoenician names were maintained or modified slightly to fit Greek phonology; thus, ʾaleph, bet, gimel became alpha, beta, gamma.

The Greek names of the following letters are more or less straightforward continuations of their Phoenician antecedents. Between Ancient and Modern Greek, they have remained largely unchanged, except that their pronunciation has followed regular sound changes along with other words (for instance, in the name of beta, ancient /b/ regularly changed to modern /v/, and ancient /ɛː/ to modern /i/, resulting in the modern pronunciation vita). The name of lambda is attested in early sources as λάβδα besides λάμβδα;[55][15] in Modern Greek the spelling is often λάμδα, reflecting pronunciation.[15] Similarly, iota is sometimes spelled γιώτα in Modern Greek ([ʝ] is conventionally transcribed ⟨γ{ι,η,υ,ει,οι}⟩ word-initially and intervocalically before back vowels and /a/). In the tables below, the Greek names of all letters are given in their traditional polytonic spelling; in modern practice, like with all other words, they are usually spelled in the simplified monotonic system.

| Letter | Name | Pronunciation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | Phoenician original | English | Greek (Ancient) | Greek (Modern) | English | |

| Α | ἄλφα | aleph | alpha | [alpʰa] | [ˈalfa] | /ˈælfə/ |

| Β | βῆτα | beth | beta | [bɛːta] | [ˈvita] | /ˈbiːtə/, US: /ˈbeɪtə/ |

| Γ | γάμμα | gimel | gamma | [ɡamma] | [ˈɣama] | /ˈɡæmə/ |

| Δ | δέλτα | daleth | delta | [delta] | [ˈðelta] | /ˈdɛltə/ |

| Η | ἦτα | heth | eta | [hɛːta], [ɛːta] | [ˈita] | /ˈiːtə/, US: /ˈeɪtə/ |

| Θ | θῆτα | teth | theta | [tʰɛːta] | [ˈθita] | /ˈθiːtə/, US: /ˈθeɪtə/ |

| Ι | ἰῶτα | yodh | iota | [iɔːta] | [ˈʝota] | /aɪˈoʊtə/ |

| Κ | κάππα | kaph | kappa | [kappa] | [ˈkapa] | /ˈkæpə/ |

| Λ | λάμβδα | lamedh | lambda | [lambda] | [ˈlamða] | /ˈlæmdə/ |

| Μ | μῦ | mem | mu | [myː] | [mi] | /mjuː/ ; occasionally US: /muː/ |

| Ν | νῦ | nun | nu | [nyː] | [ni] | /njuː/ |

| Ρ | ῥῶ | reš | rho | [rɔː] | [ro] | /roʊ/ |

| Τ | ταῦ | taw | tau | [tau] | [taf] | /taʊ, tɔː/ |

In the cases of the three historical sibilant letters below, the correspondence between Phoenician and Ancient Greek is less clear, with apparent mismatches both in letter names and sound values. The early history of these letters (and the fourth sibilant letter, obsolete san) has been a matter of some debate. Here too, the changes in the pronunciation of the letter names between Ancient and Modern Greek are regular.

| Letter | Name | Pronunciation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | Phoenician original | English | Greek (Ancient) | Greek (Modern) | English | |

| Ζ | ζῆτα | zayin | zeta | [zdɛːta] | [ˈzita] | /ˈziːtə/, US: /ˈzeɪtə/ |

| Ξ | ξεῖ, ξῖ | samekh | xi | [kseː] | [ksi] | /zaɪ, ksaɪ/ |

| Σ | σίγμα | šin | siɡma | [siɡma] | [ˈsiɣma] | /ˈsɪɡmə/ |

In the following group of consonant letters, the older forms of the names in Ancient Greek were spelled with -εῖ, indicating an original pronunciation with -ē. In Modern Greek these names are spelled with -ι.

| Letter | Name | Pronunciation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | English | Greek (Ancient) | Greek (Modern) | English | |

| Ξ | ξεῖ, ξῖ | xi | [kseː] | [ksi] | /zaɪ, ksaɪ/ |

| Π | πεῖ, πῖ | pi | [peː] | [pi] | /paɪ/ |

| Φ | φεῖ, φῖ | phi | [pʰeː] | [fi] | /faɪ/ |

| Χ | χεῖ, χῖ | chi | [kʰeː] | [çi] | /kaɪ/ |

| Ψ | ψεῖ, ψῖ | psi | [pseː] | [psi] | /saɪ/, /psaɪ/ |

The following group of vowel letters were originally called simply by their sound values as long vowels: ē, ō, ū, and ɔ. Their modern names contain adjectival qualifiers that were added during the Byzantine period, to distinguish between letters that had become confusable.[15] Thus, the letters ⟨ο⟩ and ⟨ω⟩, pronounced identically by this time, were called o mikron ("small o") and o mega ("big o").[15] The letter ⟨ε⟩ was called e psilon ("plain e") to distinguish it from the identically pronounced digraph ⟨αι⟩, while, similarly, ⟨υ⟩, which at this time was pronounced [y], was called y psilon ("plain y") to distinguish it from the identically pronounced digraph ⟨οι⟩.[15]

| Letter | Name | Pronunciation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (Ancient) | Greek (Medieval) | Greek (Modern) | English | Greek (Ancient) | Greek (Modern) | English | |

| Ε | εἶ | ἐ ψιλόν | ἔψιλον | epsilon | [eː] | [ˈepsilon] | /ˈɛpsɪlɒn/, some UK: /ɛpˈsaɪlən/ |

| Ο | οὖ | ὀ μικρόν | ὄμικρον | omicron | [oː] | [ˈomikron] | /ˈɒmɪkrɒn/, traditional UK: /oʊˈmaɪkrɒn/ |

| Υ | ὖ | ὐ ψιλόν | ὔψιλον | upsilon | [uː], [yː] | [ˈipsilon] | /juːpˈsaɪlən, ˈʊpsɪlɒn/, also UK: /ʌpˈsaɪlən/, US: /ˈʌpsɪlɒn/ |

| Ω | ὦ | ὠ μέγα | ὠμέγα | omega | [ɔː] | [oˈmeɣa] | US: /oʊˈmeɪɡə/, traditional UK: /ˈoʊmɪɡə/ |

Some dialects of the Aegean and Cypriot have retained long consonants and pronounce [ˈɣamːa] and [ˈkapʰa]; also, ήτα has come to be pronounced [ˈitʰa] in Cypriot.[56]

Letter shapes

Like Latin and other alphabetic scripts, Greek originally had only a single form of each letter, without a distinction between uppercase and lowercase. This distinction is an innovation of the modern era, drawing on different lines of development of the letter shapes in earlier handwriting.

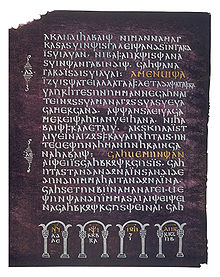

The oldest forms of the letters in antiquity are majuscule forms. Besides the upright, straight inscriptional forms (capitals) found in stone carvings or incised pottery, more fluent writing styles adapted for handwriting on soft materials were also developed during antiquity. Such handwriting has been preserved especially from papyrus manuscripts in Egypt since the Hellenistic period. Ancient handwriting developed two distinct styles: uncial writing, with carefully drawn, rounded block letters of about equal size, used as a book hand for carefully produced literary and religious manuscripts, and cursive writing, used for everyday purposes.[57] The cursive forms approached the style of lowercase letter forms, with ascenders and descenders, as well as many connecting lines and ligatures between letters.

In the ninth and tenth century, uncial book hands were replaced with a new, more compact writing style, with letter forms partly adapted from the earlier cursive.[57] This minuscule style remained the dominant form of handwritten Greek into the modern era. During the Renaissance, western printers adopted the minuscule letter forms as lowercase printed typefaces, while modeling uppercase letters on the ancient inscriptional forms. The orthographic practice of using the letter case distinction for marking proper names, titles, etc. developed in parallel to the practice in Latin and other western languages.

| Inscription | Manuscript | Modern print | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic | Classical | Uncial | Minuscule | Lowercase | Uppercase |

| α | Α | ||||

| β | Β | ||||

| γ | Γ | ||||

| δ | Δ | ||||

| ε | Ε | ||||

| ζ | Ζ | ||||

| η | Η | ||||

| θ | Θ | ||||

| ι | Ι | ||||

| κ | Κ | ||||

| λ | Λ | ||||

| μ | Μ | ||||

| ν | Ν | ||||

| ξ | Ξ | ||||

| ο | Ο | ||||

| π | Π | ||||

| ρ | Ρ | ||||

| σς | Σ | ||||

| τ | Τ | ||||

| υ | Υ | ||||

| φ | Φ | ||||

| χ | Χ | ||||

| ψ | Ψ | ||||

| ω | Ω | ||||

Derived alphabets

The Greek alphabet was the model for various others:[8]

- The Etruscan alphabet;

- The Latin alphabet, together with various other ancient scripts in Italy, adopted from an archaic form of the Greek alphabet brought to Italy by Greek colonists in the late 8th century BC, via Etruscan;

- The Gothic alphabet, devised in the 4th century AD to write the Gothic language, based on a combination of Greek and Latin uncial models;[58]

- The Glagolitic alphabet, devised in the 9th century AD for writing Old Church Slavonic;

- The Cyrillic script, which replaced the Glagolitic alphabet shortly afterwards.

- The Coptic Alphabet used for writing the Coptic language.

The Armenian and Georgian alphabets are almost certainly modeled on the Greek alphabet, but their graphic forms are quite different.[59]

Other uses

Use for other languages

Apart from the daughter alphabets listed above, which were adapted from Greek but developed into separate writing systems, the Greek alphabet has also been adopted at various times and in various places to write other languages.[60] For some of them, additional letters were introduced.

Antiquity

- Most of the Iron Age alphabets of Asia Minor were also adopted around the same time, as the early Greek alphabet was adopted from the Phoenician Alphabet. The Lydian and Carian alphabets are generally believed to derive from the Greek alphabet, although it is not clear which variant is the direct ancestor. While some of these alphabets such as Phrygian had slight differences from the Greek counterpart, some like Carian alphabet had mostly different values and several other characters inherited from pre-Greek local scripts. They were in use c. 800–300 BC until all the Anatolian languages were extinct due to Hellenization.[61][62][63][64][65]

- The original Old Italic alphabets was the early Greek alphabet with only slight modifications.

- It was used in some Paleo-Balkan languages, including Thracian. For other neighboring languages or dialects, such as Ancient Macedonian, isolated words are preserved in Greek texts, but no continuous texts are preserved.

- The Greco-Iberian alphabet was used for writing the ancient Iberian language in parts of modern Spain.

- Gaulish inscriptions (in modern France) used the Greek alphabet until the Roman conquest

- The Bactrian language, an Iranian language spoken in what is now Afghanistan, was written in the Greek alphabet during the Kushan Empire (65–250 AD). It adds an extra letter ⟨þ⟩ for the sh sound [ʃ].[66]

- Derived from Indo-Greek coinage, the coins of Nahapana and Chastana of the Western Satraps featured an Indo-Aryan language legend written in Greek or pseudo-Greek letters. The subsequent rulers' coins had the Greek script degrade to a mere ornament that no longer represented any legible legend.[67]

- The Coptic alphabet adds eight letters derived from Demotic. It is still used today, mostly in Egypt, to write Coptic, the liturgical language of Egyptian Christians. Letters usually retain an uncial form different from the forms used for Greek today. The alphabet of Old Nubian is an adaptation of Coptic.

Middle Ages

- Coins from the 4th-8th centuries known as mordovkas were used as currency in Eastern Europe by Uralic peoples and were written in Moksha using Greek uncial script.[68]

- An 8th-century Arabic fragment preserves a text in the Greek alphabet,[69] as does a 9th or 10th century psalm translation fragment.[70]

- An Old Ossetic inscription of the 10th–12th centuries found in Arxyz, the oldest known attestation of an Ossetic language.

- The Old Nubian language of Makuria (modern Sudan) adds three Coptic letters, two letters derived from Meroitic script, and a digraph of two Greek gammas used for the velar nasal sound.

- Various South Slavic dialects, similar to the modern Bulgarian and Macedonian languages, have been written in Greek script.[71][72][73][74] The modern South Slavic languages now use modified Cyrillic alphabets.

Early modern

- Turkish spoken by Orthodox Christians (Karamanlides) was often written in Greek script, and called Karamanlidika.

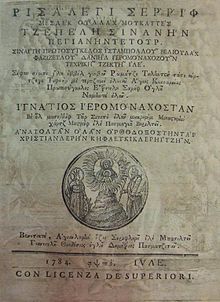

- Tosk Albanian was often written using the Greek alphabet, starting in about 1500.[75] The printing press at Moschopolis published several Albanian texts in Greek script during the 18th century. It was only in 1908 that the Monastir conference standardized a Latin orthography for both Tosk and Gheg. Greek spelling is still occasionally used for the local Albanian dialects (Arvanitika) in Greece.

- Gagauz, a Turkic language of the northeast Balkans spoken by Orthodox Christians, was apparently written in Greek characters in the late 19th century. In 1957, it was standardized on Cyrillic, and in 1996, a Gagauz alphabet based on Latin characters was adopted (derived from the Turkish alphabet).

- Surguch, a Turkic language, was spoken by a small group of Orthodox Christians in northern Greece. It is now written in Latin or Cyrillic characters.

- Urum or Greek Tatar, spoken by Orthodox Christians, used the Greek alphabet.

- Judaeo-Spanish or Ladino, a Jewish dialect of Spanish, has occasionally been published in Greek characters in Greece.[76]

- The Italian humanist Giovan Giorgio Trissino tried to add some Greek letters (Ɛ ε, Ꞷ ω) to Italian orthography in 1524.[77]

In mathematics and science

Greek symbols are used as symbols in mathematics, physics and other sciences. Many symbols have traditional uses, such as lower case epsilon (ε) for an arbitrarily small positive number, lower case pi (π) for the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, capital sigma (Σ) for summation, and lower case sigma (σ) for standard deviation. For many years the Greek alphabet was used by the World Meteorological Organization for naming North Atlantic hurricanes if a season was so active that it exhausted the regular list of storm names. This happened during the 2005 season (when Alpha through Zeta were used), and the 2020 season (when Alpha through Iota were used), after which the practice was discontinued.[78][79] In May 2021 the World Health Organization announced that the variants of SARS-CoV-2 of the virus would be named using letters of the Greek alphabet to avoid stigma and simplify communications for non-scientific audiences.[80][81]

Astronomy

Greek letters are used to denote the brighter stars within each of the eighty-eight constellations. In most constellations, the brightest star is designated Alpha and the next brightest Beta etc. For example, the brightest star in the constellation of Centaurus is known as Alpha Centauri. For historical reasons, the Greek designations of some constellations begin with a lower ranked letter.

International Phonetic Alphabet

Several Greek letters are used as phonetic symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).[82] Several of them denote fricative consonants; the rest stand for variants of vowel sounds. The glyph shapes used for these letters in specialized phonetic fonts is sometimes slightly different from the conventional shapes in Greek typography proper, with glyphs typically being more upright and using serifs, to make them conform more with the typographical character of other, Latin-based letters in the phonetic alphabet. Nevertheless, in the Unicode encoding standard, the following three phonetic symbols are considered the same characters as the corresponding Greek letters proper:[83]

| β | beta | U+03B2 | voiced bilabial fricative |

| θ | theta | U+03B8 | voiceless dental fricative |

| χ | chi | U+03C7 | voiceless uvular fricative |

On the other hand, the following phonetic letters have Unicode representations separate from their Greek alphabetic use, either because their conventional typographic shape is too different from the original, or because they also have secondary uses as regular alphabetic characters in some Latin-based alphabets, including separate Latin uppercase letters distinct from the Greek ones.

| Greek letter | Phonetic letter | Uppercase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ | phi | U+03C6 | ɸ | U+0278 | Voiceless bilabial fricative | – |

| γ | gamma | U+03B3 | ɣ | U+0263 | Voiced velar fricative | Ɣ U+0194 |

| ε | epsilon | U+03B5 | ɛ | U+025B | Open-mid front unrounded vowel | Ɛ U+0190 |

| α | alpha | U+03B1 | ɑ | U+0251 | Open back unrounded vowel | Ɑ U+2C6D |

| υ | upsilon | U+03C5 | ʊ | U+028A | near-close near-back rounded vowel | Ʊ U+01B1 |

| ι | iota | U+03B9 | ɩ | U+0269 | Obsolete for near-close near-front unrounded vowel now ɪ | Ɩ U+0196 |

The symbol in Americanist phonetic notation for the voiceless alveolar lateral fricative is the Greek letter lambda ⟨λ⟩, but ⟨ɬ⟩ in the IPA. The IPA symbol for the palatal lateral approximant is ⟨ʎ⟩, which looks similar to lambda, but is actually an inverted lowercase y.

Use as numerals

Greek letters were also used to write numbers. In the classical Ionian system, the first nine letters of the alphabet stood for the numbers from 1 to 9, the next nine letters stood for the multiples of 10, from 10 to 90, and the next nine letters stood for the multiples of 100, from 100 to 900. For this purpose, in addition to the 24 letters which by that time made up the standard alphabet, three otherwise obsolete letters were retained or revived: digamma ⟨Ϝ⟩ for 6, koppa ⟨Ϙ⟩ for 90, and a rare Ionian letter for [ss], today called sampi ⟨Ͳ⟩, for 900. This system has remained in use in Greek up to the present day, although today it is only employed for limited purposes such as enumerating chapters in a book, similar to the way Roman numerals are used in English. The three extra symbols are today written as ⟨ϛ⟩, ⟨ϟ⟩ and ⟨ϡ⟩. To mark a letter as a numeral sign, a small stroke called keraia is added to the right of it.

| Αʹ αʹ | alpha | 1 |

| Βʹ βʹ | beta | 2 |

| Γʹ γʹ | gamma | 3 |

| Δʹ δʹ | delta | 4 |

| Εʹ εʹ | epsilon | 5 |

| ϛʹ | digamma (stigma) | 6 |

| Ζʹ ζʹ | zeta | 7 |

| Ηʹ ηʹ | eta | 8 |

| Θʹ θʹ | theta | 9 |

| Ιʹ ιʹ | iota | 10 |

| Κʹ κʹ | kappa | 20 |

| Λʹ λʹ | lambda | 30 |

| Μʹ μʹ | mu | 40 |

| Νʹ νʹ | nu | 50 |

| Ξʹ ξʹ | xi | 60 |

| Οʹ οʹ | omicron | 70 |

| Πʹ πʹ | pi | 80 |

| ϟʹ | koppa | 90 |

| Ρʹ ρʹ | rho | 100 |

| Σʹ σʹ | sigma | 200 |

| Τʹ τʹ | tau | 300 |

| Υʹ υʹ | upsilon | 400 |

| Φʹ φʹ | phi | 500 |

| Χʹ χʹ | chi | 600 |

| Ψʹ ψʹ | psi | 700 |

| Ωʹ ωʹ | omega | 800 |

| ϡʹ | sampi | 900 |

Use by student fraternities and sororities

In North America, many college fraternities and sororities are named with combinations of Greek letters, and are hence also known as "Greek letter organizations".[84] This naming tradition was initiated by the foundation of the Phi Beta Kappa Society at the College of William and Mary in 1776.[84] The name of this fraternal organization is an acronym for the ancient Greek phrase Φιλοσοφία Βίου Κυβερνήτης (Philosophia Biou Kybernētēs), which means "Love of wisdom, the guide of life" and serves as the organization's motto.[84] Sometimes early fraternal organizations were known by their Greek letter names because the mottos that these names stood for were secret and revealed only to members of the fraternity.[84]

Different chapters within the same fraternity are almost always (with a handful of exceptions) designated using Greek letters as serial numbers. The founding chapter of each organization is its A chapter. As an organization expands, it establishes a B chapter, a Γ chapter, and so on and so forth. In an organization that expands to more than 24 chapters, the chapter after Ω chapter is AA chapter, followed by AB chapter, etc. Each of these is still a "chapter Letter", albeit a double-digit letter just as 10 through 99 are double-digit numbers. The Roman alphabet has a similar extended form with such double-digit letters when necessary, but it is used for columns in a table or chart rather than chapters of an organization.[85]

Glyph variants

Some letters can occur in variant shapes, mostly inherited from medieval minuscule handwriting. While their use in normal typography of Greek is purely a matter of font styles, some such variants have been given separate encodings in Unicode.

- The symbol ϐ ("curled beta") is a cursive variant form of beta (β). In the French tradition of Ancient Greek typography, β is used word-initially, and ϐ is used word-internally.

- The letter delta has a form resembling a cursive capital letter D; while not encoded as its own form, this form is included as part of the symbol for the drachma (a Δρ digraph) in the Currency Symbols block, at U+20AF (₯).

- The letter epsilon can occur in two equally frequent stylistic variants, either shaped ('lunate epsilon', like a semicircle with a stroke) or (similar to a reversed number 3). The symbol ϵ (U+03F5) is designated specifically for the lunate form, used as a technical symbol.

- The symbol ϑ ("script theta") is a cursive form of theta (θ), frequent in handwriting, and used with a specialized meaning as a technical symbol.

- The symbol ϰ ("kappa symbol") is a cursive form of kappa (κ), used as a technical symbol.

- The symbol ("variant pi") is an archaic script form of pi (π), also used as a technical symbol.

- The letter rho (ρ) can occur in different stylistic variants, with the descending tail either going straight down or curled to the right. The symbol ϱ (U+03F1) is designated specifically for the curled form, used as a technical symbol.

- The letter sigma, in standard orthography, has two variants: ς, used only at the ends of words, and σ, used elsewhere. The form ϲ ("lunate sigma", resembling a Latin c) is a medieval stylistic variant that can be used in both environments without the final/non-final distinction.

- The capital letter upsilon (Υ) can occur in different stylistic variants, with the upper strokes either straight like a Latin Y, or slightly curled. The symbol ϒ (U+03D2) is designated specifically for the curled form (), used as a technical symbol, e.g. in physics.

- The letter phi can occur in two equally frequent stylistic variants, either shaped as (a circle with a vertical stroke through it) or as (a curled shape open at the top). The symbol ϕ (U+03D5) is designated specifically for the closed form, used as a technical symbol.

- The letter omega has at least three stylistic variants of its capital form. The standard is the "open omega" (Ω), resembling an open partial circle with the opening downward and the ends curled outward. The two other stylistic variants are seen more often in modern typography, resembling a raised and underscored circle (roughly o̲), where the underscore may or may not be touching the circle on a tangent (in the former case it resembles a superscript omicron similar to that found in the numero sign or masculine ordinal indicator; in the latter, it closely resembles some forms of the Latin letter Q). The open omega is always used in symbolic settings and is encoded in Letterlike Symbols (U+2126) as a separate code point for backward compatibility.

Computer encodings

For computer usage, a variety of encodings have been used for Greek online, many of them documented in RFC 1947.

The two principal ones still used today are ISO/IEC 8859-7 and Unicode. ISO 8859-7 supports only the monotonic orthography; Unicode supports both the monotonic and polytonic orthographies.

ISO/IEC 8859-7

For the range A0–FF (hex), it follows the Unicode range 370–3CF (see below) except that some symbols, like ©, ½, § etc. are used where Unicode has unused locations. Like all ISO-8859 encodings, it is equal to ASCII for 00–7F (hex).

Greek in Unicode

Unicode supports polytonic orthography well enough for ordinary continuous text in modern and ancient Greek, and even many archaic forms for epigraphy. With the use of combining characters, Unicode also supports Greek philology and dialectology and various other specialized requirements. Most current text rendering engines do not render diacritics well, so, though alpha with macron and acute can be represented as U+03B1 U+0304 U+0301, this rarely renders well: ᾱ́.[86]

There are two main blocks of Greek characters in Unicode. The first is "Greek and Coptic" (U+0370 to U+03FF). This block is based on ISO 8859-7 and is sufficient to write Modern Greek. There are also some archaic letters and Greek-based technical symbols.

This block also supports the Coptic alphabet. Formerly, most Coptic letters shared codepoints with similar-looking Greek letters; but in many scholarly works, both scripts occur, with quite different letter shapes, so as of Unicode 4.1, Coptic and Greek were disunified. Those Coptic letters with no Greek equivalents still remain in this block (U+03E2 to U+03EF).

To write polytonic Greek, one may use combining diacritical marks or the precomposed characters in the "Greek Extended" block (U+1F00 to U+1FFF).

| Greek and Coptic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+037x | Ͱ | ͱ | Ͳ | ͳ | ʹ | ͵ | Ͷ | ͷ | ͺ | ͻ | ͼ | ͽ | ; | Ϳ | ||

| U+038x | ΄ | ΅ | Ά | · | Έ | Ή | Ί | Ό | Ύ | Ώ | ||||||

| U+039x | ΐ | Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | Ζ | Η | Θ | Ι | Κ | Λ | Μ | Ν | Ξ | Ο |

| U+03Ax | Π | Ρ | Σ | Τ | Υ | Φ | Χ | Ψ | Ω | Ϊ | Ϋ | ά | έ | ή | ί | |

| U+03Bx | ΰ | α | β | γ | δ | ε | ζ | η | θ | ι | κ | λ | μ | ν | ξ | ο |

| U+03Cx | π | ρ | ς | σ | τ | υ | φ | χ | ψ | ω | ϊ | ϋ | ό | ύ | ώ | Ϗ |

| U+03Dx | ϐ | ϑ | ϒ | ϓ | ϔ | ϕ | ϖ | ϗ | Ϙ | ϙ | Ϛ | ϛ | Ϝ | ϝ | Ϟ | ϟ |

| U+03Ex | Ϡ | ϡ | Ϣ | ϣ | Ϥ | ϥ | Ϧ | ϧ | Ϩ | ϩ | Ϫ | ϫ | Ϭ | ϭ | Ϯ | ϯ |

| U+03Fx | ϰ | ϱ | ϲ | ϳ | ϴ | ϵ | ϶ | Ϸ | ϸ | Ϲ | Ϻ | ϻ | ϼ | Ͻ | Ͼ | Ͽ |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Greek Extended[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1F0x | ἀ | ἁ | ἂ | ἃ | ἄ | ἅ | ἆ | ἇ | Ἀ | Ἁ | Ἂ | Ἃ | Ἄ | Ἅ | Ἆ | Ἇ |

| U+1F1x | ἐ | ἑ | ἒ | ἓ | ἔ | ἕ | Ἐ | Ἑ | Ἒ | Ἓ | Ἔ | Ἕ | ||||

| U+1F2x | ἠ | ἡ | ἢ | ἣ | ἤ | ἥ | ἦ | ἧ | Ἠ | Ἡ | Ἢ | Ἣ | Ἤ | Ἥ | Ἦ | Ἧ |

| U+1F3x | ἰ | ἱ | ἲ | ἳ | ἴ | ἵ | ἶ | ἷ | Ἰ | Ἱ | Ἲ | Ἳ | Ἴ | Ἵ | Ἶ | Ἷ |

| U+1F4x | ὀ | ὁ | ὂ | ὃ | ὄ | ὅ | Ὀ | Ὁ | Ὂ | Ὃ | Ὄ | Ὅ | ||||

| U+1F5x | ὐ | ὑ | ὒ | ὓ | ὔ | ὕ | ὖ | ὗ | Ὑ | Ὓ | Ὕ | Ὗ | ||||

| U+1F6x | ὠ | ὡ | ὢ | ὣ | ὤ | ὥ | ὦ | ὧ | Ὠ | Ὡ | Ὢ | Ὣ | Ὤ | Ὥ | Ὦ | Ὧ |

| U+1F7x | ὰ | ά | ὲ | έ | ὴ | ή | ὶ | ί | ὸ | ό | ὺ | ύ | ὼ | ώ | ||

| U+1F8x | ᾀ | ᾁ | ᾂ | ᾃ | ᾄ | ᾅ | ᾆ | ᾇ | ᾈ | ᾉ | ᾊ | ᾋ | ᾌ | ᾍ | ᾎ | ᾏ |

| U+1F9x | ᾐ | ᾑ | ᾒ | ᾓ | ᾔ | ᾕ | ᾖ | ᾗ | ᾘ | ᾙ | ᾚ | ᾛ | ᾜ | ᾝ | ᾞ | ᾟ |

| U+1FAx | ᾠ | ᾡ | ᾢ | ᾣ | ᾤ | ᾥ | ᾦ | ᾧ | ᾨ | ᾩ | ᾪ | ᾫ | ᾬ | ᾭ | ᾮ | ᾯ |

| U+1FBx | ᾰ | ᾱ | ᾲ | ᾳ | ᾴ | ᾶ | ᾷ | Ᾰ | Ᾱ | Ὰ | Ά | ᾼ | ᾽ | ι | ᾿ | |

| U+1FCx | ῀ | ῁ | ῂ | ῃ | ῄ | ῆ | ῇ | Ὲ | Έ | Ὴ | Ή | ῌ | ῍ | ῎ | ῏ | |

| U+1FDx | ῐ | ῑ | ῒ | ΐ | ῖ | ῗ | Ῐ | Ῑ | Ὶ | Ί | ῝ | ῞ | ῟ | |||

| U+1FEx | ῠ | ῡ | ῢ | ΰ | ῤ | ῥ | ῦ | ῧ | Ῠ | Ῡ | Ὺ | Ύ | Ῥ | ῭ | ΅ | ` |

| U+1FFx | ῲ | ῳ | ῴ | ῶ | ῷ | Ὸ | Ό | Ὼ | Ώ | ῼ | ´ | ῾ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Combining and letter-free diacritics

Combining and spacing (letter-free) diacritical marks pertaining to Greek language:

| Combining | Spacing | Sample | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+0300 | U+0060 | ( ̀ ) | "varia / grave accent" |

| U+0301 | U+00B4, U+0384 | ( ́ ) | "oxia / tonos / acute accent" |

| U+0304 | U+00AF | ( ̄ ) | "macron" |

| U+0306 | U+02D8 | ( ̆ ) | "vrachy / breve" |

| U+0308 | U+00A8 | ( ̈ ) | "dialytika / diaeresis" |

| U+0313 | U+02BC | ( ̓ ) | "psili / comma above" (spiritus lenis) |

| U+0314 | U+02BD | ( ̔ ) | "dasia / reversed comma above" (spiritus asper) |

| U+0342 | ( ͂ ) | "perispomeni" (circumflex) | |

| U+0343 | ( ̓ ) | "koronis" (= U+0313) | |

| U+0344 | U+0385 | ( ̈́ ) | "dialytika tonos" (deprecated, = U+0308 U+0301) |

| U+0345 | U+037A | ( ͅ ) | "ypogegrammeni / iota subscript". |

Encodings with a subset of the Greek alphabet

IBM code pages 437, 860, 861, 862, 863, and 865 contain the letters ΓΘΣΦΩαδεπστφ (plus β as an alternative interpretation for ß).

See also

Notes

- ^ The latest archaeological evidence functions as a terminus ante quem, with the proposed dates being placed some time earlier, see Astoreca 2021, p. 8; Powell 2012, p. 240. It is also possible that the alphabet first circulated on perishable materials, before being written on materials that can be preserved, see Lopez-Ruiz 2022, p. 231; Cook 1987, p. 9

- ^ a b Epsilon ⟨ε⟩ and omicron ⟨ο⟩ originally could denote both short and long vowels in pre-classical archaic Greek spelling, just like other vowel letters. They were restricted to the function of short vowel signs in classical Greek, as the long vowels /eː/ and /oː/ came to be spelled instead with the digraphs ⟨ει⟩ and ⟨ου⟩, having phonologically merged with a corresponding pair of former diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ respectively.

References

- ^ a b Lopez-Ruiz 2022, p. 231; Parker & Steele 2021, p. 2; Powell 2012, p. 240

- ^ The date of the earliest inscribed objects; Johnston 2003, pp. 263–276 summarizes the scholarship on the dating.

- ^ See also: Lopez-Ruiz 2022, pp. 230–231; Parker & Steele 2021, pp. 2–3; Woodard & Scott 2014, p. 3; Horrocks 2014, p. xviii; Howatson 2013, p. 35; Swiggers 1996, p. 268; Cook 1987, p. 9

- ^ The Development of the Greek Alphabet within the Chronology of the ANE Archived 2015-04-12 at the Wayback Machine (2009), Quote: "Naveh gives four major reasons why it is universally agreed that the Greek alphabet was developed from an early Phoenician alphabet.

1 According to Herodutous "the Phoenicians who came with Cadmus... brought into Hellas the alphabet, which had hitherto been unknown, as I think, to the Greeks."

2 The Greek Letters, alpha, beta, gimmel have no meaning in Greek but the meaning of most of their Semitic equivalents is known. For example, 'aleph' means 'ox', 'bet' means 'house' and 'gimmel' means 'throw stick'.

3 Early Greek letters are very similar and sometimes identical to the West Semitic letters.

4 The letter sequence between the Semitic and Greek alphabets is identical. (Naveh 1982)" - ^ Horrocks 2014, p. xviii: "By redeploying letters that that denoted consonant sounds irrelevant to Greek, the vowels could now be written systematically, thus producing the first 'true' alphabet"; Howatson 2013, p. 35; Swiggers 1996, p. 265

- ^ Howatson 2013, p. 35; Threatte 1996, p. 271

- ^ a b Horrocks 2014, p. xviii.

- ^ a b Coulmas 1996.

- ^ Threatte 1996, p. 272.

- ^ Colvin 2014, pp. 87–88; Threatte 1996, p. 272

- ^ Horrocks 2006, pp. 231–250

- ^ Woodard 2008, pp. 15–17

- ^ Holton, Mackridge & Philippaki-Warburton 1998, p. 31

- ^ a b Adams 1987, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Keller & Russell 2012, p. 5

- ^ a b c d e Mastronarde 2013, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e Groton 2013, p. 3

- ^ Matthews, Ben (May 2006). "Acquisition of Scottish English Phonology: An Overview". ResearchGate. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Hinge 2001, pp. 212–234

- ^ a b c d e f g Keller & Russell 2012, pp. 5–6

- ^ a b c d e f Mastronarde 2013, p. 11

- ^ "Net Definition & Meaning". Britannica Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ^ a b c Mastronarde 2013, pp. 11–13

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mastronarde 2013, p. 12

- ^ a b Nicholas, Nick (2004). "Sigma: final versus non-final". Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ a b c d Mastronarde 2013, p. 13

- ^ Additionally, the more ancient combination ⟨ωυ⟩ or ⟨ωϋ⟩ can occur in ancient especially in Ionic texts or in personal names.

- ^ Dickey 2007, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Dickey 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Nicolas, Nick. "Greek Unicode Issues: Punctuation Archived 2012-08-06 at archive.today". 2005. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

- ^ a b Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 499–511.

- ^ Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 499–502.

- ^ Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 499–502, 510–511.

- ^ Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 499–502, 509.

- ^ a b Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 510–511.

- ^ a b c Verbrugghe 1999, pp. 505–507, 510–511.

- ^ ISO (2010). ISO 843:1997 (Conversion of Greek characters into Latin characters). Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ UNGEGN Working Group on Romanization Systems (2003). "Greek". Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ "Greek (ALA-LC Romanization Tables)" (PDF). Library of Congress. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ Montarini & Montana 2022, pp. 18–19; Horrocks 2014, p. xviii; Powell 2012, pp. 235–236, 240; Niesiolowski-Spano 2007, p. 180

- ^ Mannack 2019, p. 31; Colvin 2014, pp. 83–84; Rose 2012, p. 96; Powell 2012, pp. 236–239

- ^ Astoreca 2021, p. 8; Powell 2012, p. 240

- ^ Woodard & Scott 2014, p. 3; Horrocks 2014, p. xviii; Howatson 2013, p. 35

- ^ Swiggers 1996, p. 268; Cook 1987, p. 9; Howatson 2013, p. 35

- ^ Colvin 2014, p. 53.

- ^ "A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language", article by Roger D. Woodward (ed. Egbert J. Bakker, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell).

- ^ Horrocks 2014, p. xviii; Coulmas 1996

- ^ Daniels 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b Voutiras 2007, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d Woodard 2010, pp. 26–46.

- ^ a b c d Jeffery 1961, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Threatte 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Horrocks 2010, p. xiix.

- ^ a b Panayotou 2007, p. 407.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1940, s.v. "λάβδα"

- ^ Newton, B. E. (1968). "Spontaneous gemination in Cypriot Greek". Lingua. 20: 15–57. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(68)90130-7. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b Thompson 1912, pp. 102–103

- ^ Murdoch 2004, p. 156

- ^ George L. Campbell, Christopher Moseley, The Routledge Handbook of Scripts and Alphabets, pp. 51ff, 96ff

- ^ Macrakis 1996.

- ^ Understanding Relations Between Scripts II Archived 2022-05-22 at the Wayback Machine by Philip J Boyes & Philippa M Steele. Published in the UK in 2020 by Oxbow Books: "The Carian alphabet resembles the Greek alphabet, though, as in the case of Phrygian, no single Greek variant can be identified as its ancestor", "It is generally assumed that the Lydian alphabet is derived from the Greek alphabet, but the exact relationship remains unclear (Melchert 2004)"

- ^ Britannica – Lycian Alphabet Archived 2024-07-10 at the Wayback Machine "The Lycian alphabet is clearly related to the Greek, but the exact nature of the relationship is uncertain. Several letters appear to be related to symbols of the Cretan and Cyprian writing systems."

- ^ Scriptsource.org – Carian Archived 2023-10-29 at the Wayback Machine"Visually, the letters bear a close resemblance to Greek letters. Decipherment was initially attempted on the assumption that those letters which looked like Greek represented the same sounds as their closest visual Greek equivalents. However it has since been established that the phonetic values of the two scripts are very different. For example the theta θ symbol represents 'th' in Greek but 'q' in Carian. Carian was generally written from left to right, although Egyptian writers wrote primarily from right to left. It was written without spaces between words."

- ^ Omniglot.com – Carian Archived 2024-08-27 at the Wayback Machine "The Carian alphabet appears in about 100 pieces of graffiti inscriptions left by Carian mercenaries who served in Egypt. A number of clay tablets, coins and monumental inscriptions have also been found. It was possibly derived from the Phoenician alphabet."

- ^ Ancient Anatolian languages and cultures in contact: some methodological observations Archived 2023-09-03 at the Wayback Machine by Paola Cotticelli-Kurras & Federico Giusfredi (University of Verona, Italy) "During the Iron ages, with a brand new political balance and cultural scenario, the cultures and languages of Anatolia maintained their position of a bridge between the Aegean and the Syro-Mesopotamian worlds, while the North-West Semitic cultures of the Phoenicians and of the Aramaeans also entered the scene. Assuming the 4th century and the hellenization of Anatolia as the terminus ante quem, the correct perspective of a contact-oriented study of the Ancient Anatolian world needs to take as an object a large net of cultures that evolved and changed over almost 16 centuries of documentary history."

- ^ Sims-Williams 1997.

- ^ Rapson, E. J. (1908). Catalogue of the Coins of the Andhra Dynasty, the Western Kṣatrapas, the Traikūṭaka Dynasty, and the 'Bodhi' Dynasty. London: Longman & Co. pp. cxci–cxciv, 65–67, 72–75. ISBN 978-1-332-41465-9.

- ^ Zaikovsky 1929

- ^ J. Blau, "Middle and Old Arabic material for the history of stress in Arabic", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 35:3:476–84 (October 1972) full text Archived 2024-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ahmad Al-Jallad, The Damascus Psalm Fragment: Middle Arabic and the Legacy of Old Ḥigāzī, in series Late Antique and Medieval Islamic Near East (LAMINE) 2, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2020; full text Archived 2021-07-11 at the Wayback Machine; see also Bible translations into Arabic

- ^ Miletich 1920.

- ^ Mazon & Vaillant 1938.

- ^ Kristophson 1974, p. 11.

- ^ Peyfuss 1989.

- ^ Elsie 1991.

- ^ Katja Šmid, "Los problemas del estudio de la lengua sefardí", Verba Hispanica 10:1:113–24 (2002) full text Archived 2024-10-07 at the Wayback Machine: "Es interesante el hecho que en Bulgaria se imprimieron unas pocas publicaciones en alfabeto cirílico búlgaro y en Grecia en alfabeto griego."

- ^ Trissino, Gian Giorgio (1524). De le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua Italiana (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2022 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "2020 hurricane season exhausts regular list of names". Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. September 21, 2020. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ "WMO Hurricane Committee retires tropical cyclone names and ends the use of Greek alphabet". Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. March 17, 2021. Archived from the original on December 18, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ "WHO announces simple, easy-to-say labels for SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest and Concern". WHO. 31 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Mohamed, Edna (2021-05-31). "Covid-19 variants to be given Greek alphabet names to avoid stigma". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge: University Press. 1999. pp. 176–181.

- ^ For chi and beta, separate codepoints for use in a Latin-script environment were added in Unicode versions 7.0 (2014) and 8.0 (2015) respectively: U+AB53 "Latin small letter chi" (ꭓ) and U+A7B5 "Latin small letter beta" (ꞵ). As of 2017, the International Phonetic Association still lists the original Greek codepoints as the standard representations of the IPA symbols in question [1] Archived 2019-10-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d Winterer 2010, p. 377.

- ^ "How To Switch From Letters to Numbers for Columns in Excel". Indeed. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Deborah. "Preliminary Guidelines to Using Unicode for Greek". Classics@ Journal. Harvard University. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

Bibliography

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1987). Essential Modern Greek Grammar. New York City: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-25133-2. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Astoreca, Natalia Elvira (2021). Early Greek Alphabetic Writing, A Linguistic Approach. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781789257465.

- Colvin, Stephen (2014). A Brief History of Ancient Greek. Wiley. ISBN 9781405149259.

- Cook, B. F. (1987). Greek inscriptions. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520061132.

- Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-631-21481-6.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195079937.

- Daniels, Peter T. "The Study of Writing Systems". In Daniels & Bright (1996).

- Swiggers, Pierre. "Transmission of the Phoenician Script to the West". In Daniels & Bright (1996).

- Threatte, Leslie. "The Greek Alphabet". In Daniels & Bright (1996).

- Dickey, Eleanor (2007). Ancient Greek Scholarship: A Guide to Finding, Reading, and Understanding Scholia, Commentaries, Lexica, and Grammatical Treatises, from Their Beginnings to the Byzantine Period. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-531293-5.

Aristophanes of Byzantium Greek diacritics.

- Elsie, Robert (1991). "Albanian Literature in Greek Script: the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth-Century Orthodox Tradition in Albanian Writing" (PDF). Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 15 (20): 20–35. doi:10.1179/byz.1991.15.1.20. S2CID 161805678. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- Groton, Anne H. (2013). From Alpha to Omega: A Beginning Course in Classical Greek. Indianapolis, Indiana: Focus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58510-473-4. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Hinge, George (2001). Die Sprache Alkmans: Textgeschichte und Sprachgeschichte (Ph.D.). University of Aarhus.

- Jeffery, Lilian H. (1961). The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece: A Study of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and Its Development from the Eighth to the Fifth Centuries B. C. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Keller, Andrew; Russell, Stephanie (2012). Learn to Read Greek, Part 1. New Haven, Connecticut and London, England: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11589-5.

- Holton, David; Mackridge, Peter; Philippaki-Warburton, Irini (1998). Grammatiki tis ellinikis glossas. Athens: Pataki.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey (2014). Greek, A History of the Language and Its Speakers (2nd illustrated ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781118785157.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey (2006). Ellinika: istoria tis glossas kai ton omiliton tis. Athens: Estia. [Greek translation of Greek: a history of the language and its speakers, London 1997]

- Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). "The Greek Alphabet". Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3415-6. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

- Howatson, M.C., ed. (2013). The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (3rd reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199548552.

- Johnston, A. W. (2003). "The alphabet". In Stampolidis, N.; Karageorghis, V (eds.). Sea Routes from Sidon to Huelva: Interconnections in the Mediterranean 16th – 6th c. B.C. Athens: Museum of Cycladic Art. pp. 263–276.

- Kristophson, Jürgen (1974). "Das Lexicon Tetraglosson des Daniil Moschopolitis". Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. 10: 4–128.

- Liddell, Henry G; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon. Archived from the original on 2023-09-24. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- Lopez-Ruiz, Carolina (2022). Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674269958.

- Macrakis, Stavros M (1996). "Character codes for Greek: Problems and modern solutions". In Macrakis, Michael (ed.). Greek letters: from tablets to pixels. Newcastle: Oak Knoll Press. p. 265.

- Mannack, Thomas (2019). "The Good, The Bad, and the Misleading: A Network of Names on (Mainly) Athenian Vases". In Ferreira, Daniela; Leão, Delfim; Rodriguez-Perez, Diana; Moraiz, Rui (eds.). Greek Art in Motion. Archaeopress Publishing. ISBN 9781789690248.

- Mastronarde, Donald J. (2013). Introduction to Attic Greek (2nd ed.). Berkeley, California, Los Angeles, California, and London, England: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27571-3. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Mazon, André; Vaillant, André (1938). L'Evangéliaire de Kulakia, un parler slave de Bas-Vardar. Bibliothèque d'études balkaniques. Vol. 6. Paris: Librairie Droz. – selections from the Gospels in Macedonian.

- Miletich, L. (1920). "Dva bŭlgarski ru̐kopisa s grŭtsko pismo". Bŭlgarski Starini. 6.

- Montarini, Franco; Montana, Fausto (2022). History of Ancient Greek Literature. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110426328.

- Murdoch, Brian (2004). "Gothic". In Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm (eds.). Early Germanic literature and culture. Woodbridge: Camden House. pp. 149–170. ISBN 9781571131997.

- Niesiolowski-Spano, Lukasz (2007). "Early alphabetic scripts and the origin of Greek letters". In Berdowski, Piotr; Blahaczek, Beata (eds.). Haec mihi animis vestris templa, Studia Classica, In Memory of Professor Leslaw Morawiecki. Instytut Historii UR. ISBN 9788360825075.

- Panayotou, A. (12 February 2007). "Ionic and Attic". A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 405–416. ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Parker, Robert; Steele, Philippa (2021). The Early Greek Alphabets, Origin, Diffusion, Uses. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198859949.

- Powell, Barry (2012). Writing, Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. Wiley. ISBN 9781118255322.

- Peyfuss, Max Demeter (1989). Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769: Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung in Erzbistum Achrida. Wiener Archiv für Geschichte des Slawentums und Osteuropas. Vol. 13. Böhlau Verlag.

- Rose, Peter W. (2012). Class in Archaic Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521768764.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1997). "New Findings in Ancient Afghanistan – the Bactrian documents discovered from the Northern Hindu-Kush". Archived from the original on 2007-06-10.

- Stevenson, Jane (2007). "Translation and the spread of the Greek and Latin alphabets in Late Antiquity". In Harald Kittel; et al. (eds.). Translation: an international encyclopedia of translation studies. Vol. 2. Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 1157–1159.

- Threatte, Leslie (1980). The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions. Vol. I: Phonology. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-007344-7. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Thompson, Edward M (1912). An introduction to Greek and Latin palaeography. Oxford: Clarendon. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139833790. ISBN 978-1-139-83379-0.

- Verbrugghe, Gerald P. (1999), "Transliteration or Transcription of Greek", The Classical World, 92 (6): 499–511, doi:10.2307/4352343, JSTOR 4352343

- Voutiras, E. (2007). "The Introduction of the Alphabet". In Christidis, Anastasios-Phoivos (ed.). A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 266–276. ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Winterer, Caroline (2010), "Fraternities and sororities", in Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (eds.), The Classical Tradition, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0, archived from the original on 2024-10-07, retrieved 2020-11-11

- Woodard, Roger D. (2010), "Phoinikeia Grammata: An Alphabet for the Greek Language", in Bakker, Egbert J. (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language, Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-118-78291-0

- Woodard, Roger D. (2008). "Attic Greek". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The ancient languages of Europe. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 14–49. ISBN 9780521684958.

- Woodard, Roger D.; Scott, David A. (2014). The Textualization of the Greek Alphabet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107028111.

- Zaikovsky, Bogdan (1929). "Mordovkas Problem". Nizhne-Volzhskaya Oblast Ethnological Scientific Society Review (36–2). Saratov: 30–32.

External links

- Greek and Coptic character list in Unicode

- Unicode collation charts – including Greek and Coptic letters, sorted by shape

- Examples of Greek handwriting

- Greek Unicode Issues (Nick Nicholas) at archive.today (archived August 5, 2012)

- Unicode FAQ – Greek Language and Script

- alphabetic test for Greek Unicode range (Alan Wood)

- numeric test for Greek Unicode range

- Classical Greek keyboard, a browser-based tool

- GFS Typefaces, a collection of free fonts by Greek Font Society