Great Plague of Marseille

The Great Plague of Marseille, also known as the Plague of Provence, was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Western Europe. Arriving in Marseille, France, in 1720, the disease killed over 100,000 people: 50,000 in the city during the next two years and another 50,000 to the north in surrounding provinces and towns.[1]

While economic activity took only a few years to recover, as trade expanded to the West Indies and Latin America, it was not until 1765 that the population returned to its pre-1720 level.

Pre-plague city

Sanitation board

At the end of the plague of 1580, the people at Marseille took some measures to attempt to control the future spread of disease. The city council of Marseille established a sanitation board, whose members were to be drawn from the city council as well as the doctors of the city. The exact founding date of the board is unknown, but its existence is first mentioned in a 1622 text of the Parliament of Aix. The newly established sanitation board made a series of recommendations to maintain the health of the city.[2]

They established a bureaucracy to maintain the health of Marseille. In addition to protecting the city from exterior vulnerabilities, the sanitation board sought to build a public infrastructure. The first public hospital of Marseille was also built during this time period and was given a full-sized staff of doctors and nurses. Additionally, the sanitation board was responsible for the accreditation of local doctors. Citing the vast amount of misinformation that propagates during a plague, the sanitation board sought to, at a minimum, provide citizens with a list of doctors who were believed to be credible.[3]

The sanitation board was one of the first executive bodies formed by the city of Marseille. It was staffed to support the board's increasing responsibilities.[citation needed]

Quarantine system

The Sanitation Board established a three-tiered control and quarantine system. Members of the board inspected all incoming ships and gave them one of three "bills of health". The “bill of health” then determined the level of access to the city by the ship and its cargo. [citation needed]

A delegation of members of the sanitation board was to greet every incoming ship. They reviewed the captain's log, which recorded every city where the ship had landed, and checked it against the sanitation board's master list of cities throughout the Mediterranean that had rumors of recent plague incidents. The delegation also inspected all the cargo, crew and passengers, looking for signs of possible disease. If the team saw signs of disease, the ship was not allowed to land at a Marseille dock. [citation needed]

If the ship passed that first test and there were no signs of disease, but the ship's itinerary included a city with documented plague activity, the ship was sent to the second tier of quarantine, at islands outside of Marseille harbour. The criteria for the lazarets were ventilation (to drive off what was thought to be the miasma of disease), be near the sea to facilitate communication and pumping of water to clean, and to be isolated yet easily accessible.[4]

Even a clean bill of health for a ship required a minimum of 18 days' quarantine at the off-island location. During such time, the crew would be held in one of the lazarettos/lazarets that were constructed around the city. The lazarettos were also classified in relation to bills of health given to the ship and individuals. With a clean bill, a crewman went to the largest quarantine site, which was equipped with stores and was large enough to accommodate many ships and crews at a time. If crew members were believed subject to a possibility of plague, they were sent to the more isolated quarantine site, which was built on an island off the coast of the Marseille harbour. The crew and passengers were required to wait there for 50 to 60 days to see if they developed any sign of plague.[5]

Once crews served their time, they were allowed into the city in order to sell their goods and enjoy themselves prior to departure.[citation needed]

Outbreak and fatalities

This great outburst of plague was the last recurrence of a pandemic of bubonic plague, following the devastating episodes which began in the early fourteenth century; the first known instance of bubonic plague in Marseille was the arrival of the Black Death in the autumn of 1347.[6] According to contemporary reports, in May 1720,Yersinia pestis arrived at the port of Marseille from the Levant upon the merchant ship Grand-Saint-Antoine. The vessel had departed from Sidon in Lebanon, having previously called at Smyrna, Tripoli[clarification needed], and plague-ridden Cyprus. A Turkish passenger was the first to be infected and soon died, followed by several crew members and the ship's surgeon. The ship was refused entry to the port of Livorno.[citation needed]

When it arrived at Marseille, it was promptly placed under quarantine in the lazaret by the port authorities.[7] Due largely to Marseille's monopoly on French trade with the Levant, this important port had a large stock of imported goods in warehouses. It was also expanding its trade with other areas of the Middle East and emerging markets in the New World. Powerful city merchants wanted the silk and cotton cargo of the ship for the great medieval fair at Beaucaire and pressured authorities to lift the quarantine. [citation needed] [8]

A few days later, the disease broke out in the city. Hospitals were quickly overwhelmed, and residents panicked, driving the sick from their homes and out of the city. Mass graves were dug but were quickly filled. Eventually, the number of dead overcame city public health efforts, until thousands of corpses lay scattered and in piles around the city.[citation needed]

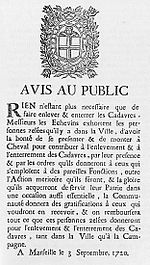

Attempts to stop the spread of plague included an Act of the Parlement of Aix that levied the death penalty for any communication between Marseille and the rest of Provence. To enforce this separation, a plague wall, or mur de la peste, was erected across the countryside. The wall was built of dry stone, 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high and 70 cm (28 in) thick, with guard posts set back from the wall. Remains of the wall can still be seen in different parts of the Plateau de Vaucluse.[citation needed]

At the onset of the plague, Nicolas Roze, who had been vice-consul at a factory on the Peloponnese coast and dealt against epidemics there, proposed his services to the local authorities, the échevins. On the strength of his experience dealing with the Greek outbreaks, he was made General Commissioner for the Rive-Neuve neighbourhood. He established a quarantine by setting up checkpoints, and went as far as building gallows as a deterrence against looters. He also had five large mass graves dug out, converted La Corderie into a field hospital, and organised distribution of humanitarian supply to the population. He furthermore organised supply for the city itself.[9]

On 16 September 1720, Roze personally headed a 150-strong group of volunteers and prisoners to remove 1,200 corpses in the poor neighbourhood of the Esplanade de la Tourette. Some of the corpses were three weeks old and contemporary sources describe them as "hardly human in shape and set in movement by maggots". In half an hour, the corpses were thrown into open pits that were then filled with lime and covered with soil.[9]

Out of 1,200 volunteers and prisoners deployed to fight the plague, only three survived. Roze himself caught the disease, but survived, although chances of survival without modern medicine are between 20 and 40%.[9]

During a two-year period, 50,000 of Marseille's total population of 90,000 died. An additional 50,000 people in other areas succumbed as the plague spread north, eventually reaching Aix-en-Provence, Arles, Apt and Toulon. Estimates indicate an overall death rate of between 25 and 50% for the population in the larger area, with the city of Marseille at 40%, the area of Toulon at above 50%, and the area of Aix and Arles at 25%.[citation needed]

After the plague subsided, the royal government strengthened the plague defenses of the port, building the waterside Lazaret d'Arenc. A double line of fifteen-foot walls ringed the whitewashed compound, pierced on the waterside to permit the offloading of cargo from lighters. Merchantmen were required to pass inspection at an island further out in the harbour, where crews and cargoes were examined.[10]

Recent research

In 1998, an excavation of a mass grave of victims of the bubonic plague outbreak was conducted by scholars from the Université de la Méditerranée.[11] The excavation provided an opportunity to study more than 200 skeletons from an area in the second arrondissement in Marseille, known as the Monastery of the Observance. In addition to modern laboratory testing, archival records were studied to determine the conditions and dates surrounding the use of this mass grave. This multidisciplinary approach revealed previously unknown facts and insights concerning the epidemic of 1722. The reconstruction of the skull of one body, a 15-year-old boy, revealed the first historical evidence of an autopsy dated to the spring of 1722. The anatomic techniques used appear to be identical to those described in a surgical book dating from 1708.[citation needed]

See also

- List of Bubonic plague outbreaks

- Plague of Justinian

- Popular revolt in late medieval Europe

- Moscow plague riot of 1771

- Second plague pandemic

- Third plague pandemic

- Nicolas Roze (chevalier)

- COVID-19 in France

Notes

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci, 2004

- ^ p. 17 Françoise Hildesheimer

- ^ p. 53, Françoise Hildesheimer

- ^ p. 361, Roger Duchêne et Jean Contrucci

- ^ p. 366, Roger Duchêne et Jean Contrucci

- ^ Duchene and Contrucci (2004), Chronology. Marseille suffered from epidemics of the European Black Death in 1348 (recurring intermittently until 1361), in 1580 and 1582, and in 1649–1650.

- ^ Duchêne & Contrucci (2004), pp. 361–362.

- ^ p. 17-19 Cindy Ermus

- ^ a b c "Nicolas Roze". hospitaliers-saint-lazare.org (in French). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ "La peste et les lazarets de Marseille" Archived 2022-02-18 at the Wayback Machine; briefly noted in Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (1995): 245f.

- ^ Signoli, Seguy, Biraben, Dutour & Belle (2002).

References

- Devaux, Christian (2013). "Small oversights that led to the Great Plague of Marseille (1720–1723): Lessons from the past". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 14 (March 2013): 169–185. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2012.11.016. PMID 23246639. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Duchêne, Roger; Contrucci, Jean (2004), Marseille, 2,600 ans d'histoire (in French), Fayard, ISBN 978-2-213-60197-7, Chapter 42, pages 360–378.

- Ermus, Cindy (2023), The Great Plague Scare of 1720: Disaster and Diplomacy in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, Cambridge University Press.

- Hildesheimer, Françoise (1980), Le Bureau de la santé de Marseille sous l'Ancien Régime. Le renfermement de la contagion, Fédération historique de Provence

- Signoli, Michel; Seguy, Isabelle; Biraben, Jean-Noel; Dutour, Olivier; Belle, Paul (2002), "Paleodemography and Historical Demography in the Context of an Epidemic: Plague in Provence in the Eighteenth Century", Population, 57 (6): 829–854, doi:10.2307/3246618, JSTOR 3246618

External links

Media related to Great Plague of Marseille at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Great Plague of Marseille at Wikimedia Commons