Thylakoid

| Cell biology | |

|---|---|

| Chloroplast | |

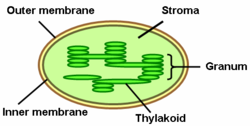

Components of a typical chloroplast

1 Granum

3 Thylakoid ◄ You are here

4 Stromal thylakoid |

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thylakoids frequently form stacks of disks referred to as grana (singular: granum). Grana are connected by intergranal or stromal thylakoids, which join granum stacks together as a single functional compartment.

In thylakoid membranes, chlorophyll pigments are found in packets called quantasomes. Each quantasome contains 230 to 250 chlorophyll molecules.

Etymology

The word Thylakoid comes from the Greek word thylakos or θύλακος, meaning "sac" or "pouch".[1] Thus, thylakoid means "sac-like" or "pouch-like".

Structure

Thylakoids are membrane-bound structures embedded in the chloroplast stroma. A stack of thylakoids is called a granum and resembles a stack of coins.

Membrane

The thylakoid membrane is the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis with the photosynthetic pigments embedded directly in the membrane. It is an alternating pattern of dark and light bands measuring each 1 nanometre.[3] The thylakoid lipid bilayer shares characteristic features with prokaryotic membranes and the inner chloroplast membrane. For example, acidic lipids can be found in thylakoid membranes, cyanobacteria and other photosynthetic bacteria and are involved in the functional integrity of the photosystems.[4] The thylakoid membranes of higher plants are composed primarily of phospholipids[5] and galactolipids that are asymmetrically arranged along and across the membranes.[6] Thylakoid membranes are richer in galactolipids rather than phospholipids; also they predominantly consist of hexagonal phase II forming monogalacotosyl diglyceride lipid. Despite this unique composition, plant thylakoid membranes have been shown to assume largely lipid-bilayer dynamic organization.[7] Lipids forming the thylakoid membranes, richest in high-fluidity linolenic acid[8] are synthesized in a complex pathway involving exchange of lipid precursors between the endoplasmic reticulum and inner membrane of the plastid envelope and transported from the inner membrane to the thylakoids via vesicles.[9]

Lumen

The thylakoid lumen is a continuous aqueous phase enclosed by the thylakoid membrane. It plays an important role for photophosphorylation during photosynthesis. During the light-dependent reaction, protons are pumped across the thylakoid membrane into the lumen making it acidic down to pH 4.

Granum and stroma lamellae

In higher plants thylakoids are organized into a granum-stroma membrane assembly. A granum (plural grana) is a stack of thylakoid discs. Chloroplasts can have from 10 to 100 grana. Grana are connected by stroma thylakoids, also called intergranal thylakoids or lamellae. Grana thylakoids and stroma thylakoids can be distinguished by their different protein composition. Grana contribute to chloroplasts' large surface area to volume ratio. A recent electron tomography study of the thylakoid membranes has shown that the stroma lamellae are organized in wide sheets perpendicular to the grana stack axis and form multiple right-handed helical surfaces at the granal interface.[2] Left-handed helical surfaces consolidate between the right-handed helices and sheets. This complex network of alternating helical membrane surfaces of different radii and pitch was shown to minimize the surface and bending energies of the membranes.[2] This new model, the most extensive one generated to date, revealed that features from two, seemingly contradictory, older models[10][11] coexist in the structure. Notably, similar arrangements of helical elements of alternating handedness, often referred to as "parking garage" structures, were proposed to be present in the endoplasmic reticulum[12] and in ultradense nuclear matter.[13][14][15] This structural organization may constitute a fundamental geometry for connecting between densely packed layers or sheets.[2]

Formation

Chloroplasts develop from proplastids when seedlings emerge from the ground. Thylakoid formation requires light. In the plant embryo and in the absence of light, proplastids develop into etioplasts that contain semicrystalline membrane structures called prolamellar bodies. When exposed to light, these prolamellar bodies develop into thylakoids. This does not happen in seedlings grown in the dark, which undergo etiolation. An underexposure to light can cause the thylakoids to fail. This causes the chloroplasts to fail resulting to the death of the plant.

Thylakoid formation requires the action of vesicle-inducing protein in plastids 1 (VIPP1). Plants cannot survive without this protein, and reduced VIPP1 levels lead to slower growth and paler plants with reduced ability to photosynthesize. VIPP1 appears to be required for basic thylakoid membrane formation, but not for the assembly of protein complexes of the thylakoid membrane.[16] It is conserved in all organisms containing thylakoids, including cyanobacteria,[17] green algae, such as Chlamydomonas,[18] and higher plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana.[19]

Isolation and fractionation

Thylakoids can be purified from plant cells using a combination of differential and gradient centrifugation.[20] Disruption of isolated thylakoids, for example by mechanical shearing, releases the lumenal fraction. Peripheral and integral membrane fractions can be extracted from the remaining membrane fraction. Treatment with sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) detaches peripheral membrane proteins, whereas treatment with detergents and organic solvents solubilizes integral membrane proteins.

Proteins

Thylakoids contain many integral and peripheral membrane proteins, as well as lumenal proteins. Recent proteomics studies of thylakoid fractions have provided further details on the protein composition of the thylakoids.[21] These data have been summarized in several plastid protein databases that are available online.[22][23]

According to these studies, the thylakoid proteome consists of at least 335 different proteins. Out of these, 89 are in the lumen, 116 are integral membrane proteins, 62 are peripheral proteins on the stroma side, and 68 peripheral proteins on the lumenal side. Additional low-abundance lumenal proteins can be predicted through computational methods.[20][24] Of the thylakoid proteins with known functions, 42% are involved in photosynthesis. The next largest functional groups include proteins involved in protein targeting, processing and folding with 11%, oxidative stress response (9%) and translation (8%).[22]

Integral membrane proteins

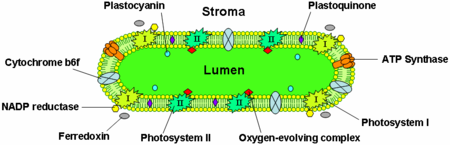

Thylakoid membranes contain integral membrane proteins which play an important role in light-harvesting and the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. There are four major protein complexes in the thylakoid membrane:

Photosystem II is located mostly in the grana thylakoids, whereas photosystem I and ATP synthase are mostly located in the stroma thylakoids and the outer layers of grana. The cytochrome b6f complex is distributed evenly throughout thylakoid membranes. Due to the separate location of the two photosystems in the thylakoid membrane system, mobile electron carriers are required to shuttle electrons between them. These carriers are plastoquinone and plastocyanin. Plastoquinone shuttles electrons from photosystem II to the cytochrome b6f complex, whereas plastocyanin carries electrons from the cytochrome b6f complex to photosystem I.

Together, these proteins make use of light energy to drive electron transport chains that generate a chemiosmotic potential across the thylakoid membrane and NADPH, a product of the terminal redox reaction. The ATP synthase uses the chemiosmotic potential to make ATP during photophosphorylation.

Photosystems

These photosystems are light-driven redox centers, each consisting of an antenna complex that uses chlorophylls and accessory photosynthetic pigments such as carotenoids and phycobiliproteins to harvest light at a variety of wavelengths. Each antenna complex has between 250 and 400 pigment molecules and the energy they absorb is shuttled by resonance energy transfer to a specialized chlorophyll a at the reaction center of each photosystem. When either of the two chlorophyll a molecules at the reaction center absorb energy, an electron is excited and transferred to an electron-acceptor molecule. Photosystem I contains a pair of chlorophyll a molecules, designated P700, at its reaction center that maximally absorbs 700 nm light. Photosystem II contains P680 chlorophyll that absorbs 680 nm light best (note that these wavelengths correspond to deep red – see the visible spectrum). The P is short for pigment and the number is the specific absorption peak in nanometers for the chlorophyll molecules in each reaction center. This is the green pigment present in plants that is not visible to unaided eyes.

Cytochrome b6f complex

The cytochrome b6f complex is part of the thylakoid electron transport chain and couples electron transfer to the pumping of protons into the thylakoid lumen. Energetically, it is situated between the two photosystems and transfers electrons from photosystem II-plastoquinone to plastocyanin-photosystem I.

ATP synthase

The thylakoid ATP synthase is a CF1FO-ATP synthase similar to the mitochondrial ATPase. It is integrated into the thylakoid membrane with the CF1-part sticking into the stroma. Thus, ATP synthesis occurs on the stromal side of the thylakoids where the ATP is needed for the light-independent reactions of photosynthesis.

Lumen proteins

The electron transport protein plastocyanin is present in the lumen and shuttles electrons from the cytochrome b6f protein complex to photosystem I. While plastoquinones are lipid-soluble and therefore move within the thylakoid membrane, plastocyanin moves through the thylakoid lumen.

The lumen of the thylakoids is also the site of water oxidation by the oxygen evolving complex associated with the lumenal side of photosystem II.

Lumenal proteins can be predicted computationally based on their targeting signals. In Arabidopsis, out of the predicted lumenal proteins possessing the Tat signal, the largest groups with known functions are 19% involved in protein processing (proteolysis and folding), 18% in photosynthesis, 11% in metabolism, and 7% redox carriers and defense.[20]

Protein expression

Chloroplasts have their own genome, which encodes a number of thylakoid proteins. However, during the course of plastid evolution from their cyanobacterial endosymbiotic ancestors, extensive gene transfer from the chloroplast genome to the cell nucleus took place. This results in the four major thylakoid protein complexes being encoded in part by the chloroplast genome and in part by the nuclear genome. Plants have developed several mechanisms to co-regulate the expression of the different subunits encoded in the two different organelles to assure the proper stoichiometry and assembly of these protein complexes. For example, transcription of nuclear genes encoding parts of the photosynthetic apparatus is regulated by light. Biogenesis, stability and turnover of thylakoid protein complexes are regulated by phosphorylation via redox-sensitive kinases in the thylakoid membranes.[25] The translation rate of chloroplast-encoded proteins is controlled by the presence or absence of assembly partners (control by epistasy of synthesis).[26] This mechanism involves negative feedback through binding of excess protein to the 5' untranslated region of the chloroplast mRNA.[27] Chloroplasts also need to balance the ratios of photosystem I and II for the electron transfer chain. The redox state of the electron carrier plastoquinone in the thylakoid membrane directly affects the transcription of chloroplast genes encoding proteins of the reaction centers of the photosystems, thus counteracting imbalances in the electron transfer chain.[28]

Protein targeting to the thylakoids

Thylakoid proteins are targeted to their destination via signal peptides and prokaryotic-type secretory pathways inside the chloroplast. Most thylakoid proteins encoded by a plant's nuclear genome need two targeting signals for proper localization: An N-terminal chloroplast targeting peptide (shown in yellow in the figure), followed by a thylakoid targeting peptide (shown in blue). Proteins are imported through the translocon of the outer and inner membrane (Toc and Tic) complexes. After entering the chloroplast, the first targeting peptide is cleaved off by a protease processing imported proteins. This unmasks the second targeting signal and the protein is exported from the stroma into the thylakoid in a second targeting step. This second step requires the action of protein translocation components of the thylakoids and is energy-dependent. Proteins are inserted into the membrane via the SRP-dependent pathway (1), the Tat-dependent pathway (2), or spontaneously via their transmembrane domains (not shown in the figure). Lumenal proteins are exported across the thylakoid membrane into the lumen by either the Tat-dependent pathway (2) or the Sec-dependent pathway (3) and released by cleavage from the thylakoid targeting signal. The different pathways utilize different signals and energy sources. The Sec (secretory) pathway requires ATP as an energy source and consists of SecA, which binds to the imported protein and a Sec membrane complex to shuttle the protein across. Proteins with a twin arginine motif in their thylakoid signal peptide are shuttled through the Tat (twin arginine translocation) pathway, which requires a membrane-bound Tat complex and the pH gradient as an energy source. Some other proteins are inserted into the membrane via the SRP (signal recognition particle) pathway. The chloroplast SRP can interact with its target proteins either post-translationally or co-translationally, thus transporting imported proteins as well as those that are translated inside the chloroplast. The SRP pathway requires GTP and the pH gradient as energy sources. Some transmembrane proteins may also spontaneously insert into the membrane from the stromal side without energy requirement.[29]

Function

The thylakoids are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. These include light-driven water oxidation and oxygen evolution, the pumping of protons across the thylakoid membranes coupled with the electron transport chain of the photosystems and cytochrome complex, and ATP synthesis by the ATP synthase utilizing the generated proton gradient.

Water photolysis

The first step in photosynthesis is the light-driven reduction (splitting) of water to provide the electrons for the photosynthetic electron transport chains as well as protons for the establishment of a proton gradient. The water-splitting reaction occurs on the lumenal side of the thylakoid membrane and is driven by the light energy captured by the photosystems. This oxidation of water conveniently produces the waste product O2 that is vital for cellular respiration. The molecular oxygen formed by the reaction is released into the atmosphere.

Electron transport chains

Two different variations of electron transport are used during photosynthesis:

- Noncyclic electron transport or non-cyclic photophosphorylation produces NADPH + H+ and ATP.

- Cyclic electron transport or cyclic photophosphorylation produces only ATP.

The noncyclic variety involves the participation of both photosystems, while the cyclic electron flow is dependent on only photosystem I.

- Photosystem I uses light energy to reduce NADP+ to NADPH + H+, and is active in both noncyclic and cyclic electron transport. In cyclic mode, the energized electron is passed down a chain that ultimately returns it (in its base state) to the chlorophyll that energized it.

- Photosystem II uses light energy to oxidize water molecules, producing electrons (e−), protons (H+), and molecular oxygen (O2), and is only active in noncyclic transport. Electrons in this system are not conserved, but are rather continually entering from oxidized 2H2O (O2 + 4 H+ + 4 e−) and exiting with NADP+ when it is finally reduced to NADPH.

Chemiosmosis

A major function of the thylakoid membrane and its integral photosystems is the establishment of chemiosmotic potential. The carriers in the electron transport chain use some of the electron's energy to actively transport protons from the stroma to the lumen. During photosynthesis, the lumen becomes acidic, as low as pH 4, compared to pH 8 in the stroma.[30] This represents a 10,000 fold concentration gradient for protons across the thylakoid membrane.

Source of proton gradient

The protons in the lumen come from three primary sources.

- Photolysis by photosystem II oxidises water to oxygen, protons and electrons in the lumen.

- The transfer of electrons from photosystem II to plastoquinone during non-cyclic electron transport consumes two protons from the stroma. These are released in the lumen when the reduced plastoquinol is oxidized by the cytochrome b6f protein complex on the lumen side of the thylakoid membrane. From the plastoquinone pool, electrons pass through the cytochrome b6f complex. This integral membrane assembly resembles cytochrome bc1.

- The reduction of plastoquinone by ferredoxin during cyclic electron transport also transfers two protons from the stroma to the lumen.

The proton gradient is also caused by the consumption of protons in the stroma to make NADPH from NADP+ at the NADP reductase.

ATP generation

The molecular mechanism of ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) generation in chloroplasts is similar to that in mitochondria and takes the required energy from the proton motive force (PMF).[citation needed] However, chloroplasts rely more on the chemical potential of the PMF to generate the potential energy required for ATP synthesis. The PMF is the sum of a proton chemical potential (given by the proton concentration gradient) and a transmembrane electrical potential (given by charge separation across the membrane). Compared to the inner membranes of mitochondria, which have a significantly higher membrane potential due to charge separation, thylakoid membranes lack a charge gradient.[citation needed] To compensate for this, the 10,000 fold proton concentration gradient across the thylakoid membrane is much higher compared to a 10 fold gradient across the inner membrane of mitochondria. The resulting chemiosmotic potential between the lumen and stroma is high enough to drive ATP synthesis using the ATP synthase. As the protons travel back down the gradient through channels in ATP synthase, ADP + Pi are combined into ATP. In this manner, the light-dependent reactions are coupled to the synthesis of ATP via the proton gradient.[citation needed]

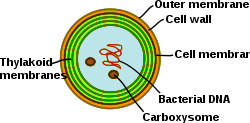

Thylakoid membranes in cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic prokaryotes with highly differentiated membrane systems. Cyanobacteria have an internal system of thylakoid membranes where the fully functional electron transfer chains of photosynthesis and respiration reside. The presence of different membrane systems lends these cells a unique complexity among bacteria. Cyanobacteria must be able to reorganize the membranes, synthesize new membrane lipids, and properly target proteins to the correct membrane system. The outer membrane, plasma membrane, and thylakoid membranes each have specialized roles in the cyanobacterial cell. Understanding the organization, functionality, protein composition, and dynamics of the membrane systems remains a great challenge in cyanobacterial cell biology.[31]

In contrast to the thylakoid network of higher plants, which is differentiated into grana and stroma lamellae, the thylakoids in cyanobacteria are organized into multiple concentric shells that split and fuse to parallel layers forming a highly connected network. This results in a continuous network that encloses a single lumen (as in higher‐plant chloroplasts) and allows water‐soluble and lipid‐soluble molecules to diffuse through the entire membrane network. Moreover, perforations are often observed within the parallel thylakoid sheets. These gaps in the membrane allow for the traffic of particles of different sizes throughout the cell, including ribosomes, glycogen granules, and lipid bodies.[32] The relatively large distance between the thylakoids provides space for the external light-harvesting antennae, the phycobilisomes.[33] This macrostructure, as in the case of higher plants, shows some flexibility during changes in the physicochemical environment.[34]

See also

- Arthur Meyer (botanist)

- André Jagendorf

- Chemiosmosis

- Electrochemical gradient

- Endosymbiosis

- Oxygen evolution

- Photosynthesis

References

- ^ θύλακος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ a b c d e Bussi Y, Shimoni E, Weiner A, Kapon R, Charuvi D, Nevo R, Efrati E, Reich Z (2019). "Fundamental helical geometry consolidates the plant photosynthetic membrane". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116 (44): 22366–22375. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11622366B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1905994116. PMC 6825288. PMID 31611387.

- ^ "Photosynthesis" McGraw Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 10th ed. 2007. Vol. 13 p. 469

- ^ Sato N (2004). "Roles of the acidic lipids sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol and phosphatidylglycerol in photosynthesis: their specificity and evolution". J Plant Res. 117 (6): 495–505. Bibcode:2004JPlR..117..495S. doi:10.1007/s10265-004-0183-1. PMID 15538651. S2CID 27225926.

- ^ "photosynthesis."Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 9 Apr. 2008

- ^ Spraque SG (1987). "Structural and functional organization of galactolipids on thylakoid membrane organization". J Bioenerg Biomembr. 19 (6): 691–703. doi:10.1007/BF00762303. PMID 3320041. S2CID 6076741.

- ^ YashRoy, R.C. (1990). "Magnetic resonance studies of dynamic organization of lipids in chloroplast membranes" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 15 (4): 281–288. doi:10.1007/bf02702669. S2CID 360223.

- ^ YashRoy, R.C. (1987). "13C NMR studies of lipid fatty-acyl chains of chloroplast membranes". Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 24 (3): 177–178. PMID 3428918.

- ^ Benning C, Xu C, Awai K (2006). "Non-vesicular and vesicular lipid trafficking involving plastids". Curr Opin Plant Biol. 9 (3): 241–7. Bibcode:2006COPB....9..241B. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.012. PMID 16603410.

- ^ Shimoni E, Rav-Hon O, Ohad I, Brumfeld V, Reich Z (2005). "Three-dimensional organization of higher-plant chloroplast thylakoid membranes revealed by electron tomography". Plant Cell. 17 (9): 2580–6. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.035030. PMC 1197436. PMID 16055630.

- ^ Mustárdy, L.; Buttle, K.; Steinbach, G.; Garab, G. (2008). "The Three-Dimensional Network of the Thylakoid Membranes in Plants: Quasihelical Model of the Granum-Stroma Assembly". Plant Cell. 20 (10): 2552–2557. doi:10.1105/tpc.108.059147. PMC 2590735. PMID 18952780.

- ^ Terasaki M, Shemesh T, Kasthuri N, Klemm R, Schalek R, Hayworth K, Hand A, Yankova M, Huber G, Lichtman J, Rapoport T, Kozlov M (2013). "Stacked endoplasmic reticulum sheets are connected by helicoidal membrane motifs". Cell. 154 (2): 285–96. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.031. PMC 3767119. PMID 23870120.

- ^ Berry DK; Caplan ME; Horowitz CJ; Huber G; Schneider AS (2016). ""Parking-garage" structures in nuclear astrophysics and cellular biophysics". Physical Review C. 94 (5). American Physical Society: 055801. arXiv:1509.00410. Bibcode:2016PhRvC..94e5801B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.94.055801. S2CID 36462725.

- ^ Horowitz CJ; Berry DK; Briggs CM; Caplan ME; Cumming A; Schneider AS (2015). "Disordered nuclear pasta, magnetic field decay, and crust cooling in neutron stars". Phys Rev Lett. 114 (3): 031102. arXiv:1410.2197. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.114c1102H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.031102. PMID 25658989. S2CID 12021024.

- ^ Schneider AS; Berry DK; Caplan ME; Horowitz CJ; Lin Z (2016). "Effect of topological defects on "nuclear pasta" observables". Physical Review C. 93 (6): 065806. arXiv:1602.03215. Bibcode:2016PhRvC..93f5806S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.93.065806. S2CID 28272522.

- ^ Elena Aseeva; Friederich Ossenbühl; Claudia Sippel; Won K. Cho; Bernhard Stein; Lutz A. Eichacker; Jörg Meurer; Gerhard Wanner; Peter Westhoff; Jürgen Soll; Ute C. Vothknecht (2007). "Vipp1 is required for basic thylakoid membrane formation but not for the assembly of thylakoid protein complexes". Plant Physiol Biochem. 45 (2): 119–28. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.01.005. PMID 17346982.

- ^ Westphal S, Heins L, Soll J, Vothknecht U (2001). "Vipp1 deletion mutant of Synechocystis: A connection between bacterial phage shock and thylakoid biogenesis?". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (7): 4243–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.061501198. PMC 31210. PMID 11274448.

- ^ Liu C, Willmund F, Golecki J, Cacace S, Markert C, Heß B, Schroda M, Schroda M (2007). "The chloroplast HSP70B-CDJ2-CGE1 chaperones catalyse assembly and disassembly of VIPP1 oligomers in Chlamydomonas". Plant J. 50 (2): 265–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03047.x. PMID 17355436.

- ^ Kroll D, Meierhoff K, Bechtold N, Kinoshita M, Westphal S, Vothknecht U, Soll J, Westhoff P (2001). "VIPP1, a nuclear gene of Arabidopsis thaliana essential for thylakoid membrane formation". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (7): 4238–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.061500998. PMC 31209. PMID 11274447.

- ^ a b c Peltier J, Emanuelsson O, Kalume D, Ytterberg J, Friso G, Rudella A, Liberles D, Söderberg L, Roepstorff P, von Heijne G, van Wijk KJ (2002). "Central Functions of the Lumenal and Peripheral Thylakoid Proteome of Arabidopsis Determined by Experimentation and Genome-Wide Prediction". Plant Cell. 14 (1): 211–36. doi:10.1105/tpc.010304. PMC 150561. PMID 11826309.

- ^ van Wijk K (2004). "Plastid proteomics". Plant Physiol Biochem. 42 (12): 963–77. Bibcode:2004PlPB...42..963V. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.10.015. PMID 15707834.

- ^ a b Friso G, Giacomelli L, Ytterberg A, Peltier J, Rudella A, Sun Q, Wijk K (2004). "In-Depth Analysis of the Thylakoid Membrane Proteome of Arabidopsis thaliana Chloroplasts: New Proteins, New Functions, and a Plastid Proteome Database". Plant Cell. 16 (2): 478–99. doi:10.1105/tpc.017814. PMC 341918. PMID 14729914.- The Plastid Proteome Database

- ^ Kleffmann T, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Gruissem W, Baginsky S (2006). "plprot: a comprehensive proteome database for different plastid types". Plant Cell Physiol. 47 (3): 432–6. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcj005. PMID 16418230. – Plastid Protein Database

- ^ Peltier J, Friso G, Kalume D, Roepstorff P, Nilsson F, Adamska I, van Wijk K (2000). "Proteomics of the Chloroplast: Systematic Identification and Targeting Analysis of Lumenal and Peripheral Thylakoid Proteins". Plant Cell. 12 (3): 319–41. doi:10.1105/tpc.12.3.319. PMC 139834. PMID 10715320.

- ^ Vener AV, Ohad I, Andersson B (1998). "Protein phosphorylation and redox sensing in chloroplast thylakoids". Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1 (3): 217–23. Bibcode:1998COPB....1..217V. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80107-6. PMID 10066592.

- ^ Choquet Y, Wostrikoff K, Rimbault B, Zito F, Girard-Bascou J, Drapier D, Wollman F (2001). "Assembly-controlled regulation of chloroplast gene translation". Biochem Soc Trans. 29 (Pt 4): 421–6. doi:10.1042/BST0290421. PMID 11498001.

- ^ Minai L, Wostrikoff K, Wollman F, Choquet Y (2006). "Chloroplast Biogenesis of Photosystem II Cores Involves a Series of Assembly-Controlled Steps That Regulate Translation". Plant Cell. 18 (1): 159–75. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.037705. PMC 1323491. PMID 16339851.

- ^ Allen J, Pfannschmidt T (2000). "Balancing the two photosystems: photosynthetic electron transfer governs transcription of reaction centre genes in chloroplasts". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 355 (1402): 1351–9. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0697. PMC 1692884. PMID 11127990.

- ^ a b Gutensohn M, Fan E, Frielingsdorf S, Hanner P, Hou B, Hust B, Klösgen R (2006). "Toc, Tic, Tat et al.: structure and function of protein transport machineries in chloroplasts". J. Plant Physiol. 163 (3): 333–47. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2005.11.009. PMID 16386331.

- ^ Jagendorf A. T. and E. Uribe (1966). "ATP formation caused by acid-base transition of spinach chloroplasts". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 55 (1): 170–177. Bibcode:1966PNAS...55..170J. doi:10.1073/pnas.55.1.170. PMC 285771. PMID 5220864.

- ^ Herrero, Antonia; Flores, Enrique, eds. (2008). The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics and Evolution (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-15-8.

- ^ Nevo R, Charuvi D, Shimoni E, Schwarz R, Kaplan A, Ohad I, Reich Z (2007). "Thylakoid membrane perforations and connectivity enable intracellular traffic in cyanobacteria". EMBO J. 26 (5): 1467–1473. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601594. PMC 1817639. PMID 17304210.

- ^ Olive, J; Ajlani, G; Astier, C; Recouvreur, M; Vernotte, C (1997). "Ultrastructure and light adaptation of phycobilisome mutants of Synechocystis PCC 6803". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1319 (2–3): 275–282. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(96)00168-5.

- ^ Nagy, G; Posselt, D; Kovács, L; Holm, JK; Szabó, M; Ughy, B; Rosta, L; Peters, J; Timmins, P; Garab, G (1 June 2011). "Reversible membrane reorganizations during photosynthesis in vivo: revealed by small-angle neutron scattering" (PDF). The Biochemical Journal. 436 (2): 225–30. doi:10.1042/BJ20110180. PMID 21473741.

Textbook sources

- Heller, H. Craig; Orians, Gordan H.; Purves, William K. & Sadava, David (2004). LIFE: The Science of Biology (7th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7167-9856-9.

- Raven, Peter H.; Ray F. Evert; Susan E. Eichhorn (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 115–127. ISBN 978-0-7167-1007-3.

- Herrero, Antonia; Flores, Enrique, eds. (2008). The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics and Evolution (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-15-8.