Grant's Canal

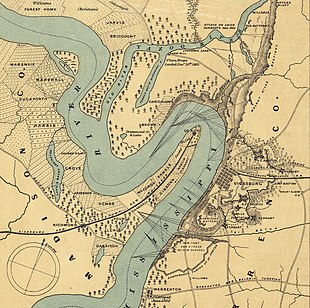

Grant's Canal (also known as Williams's Canal) was an incomplete military effort to construct a canal through De Soto Point in Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from Vicksburg, Mississippi. During the American Civil War, the Union Navy attempted to capture the Confederate-held city of Vicksburg in 1862, but were unable to do so with army support. Union Brigadier-General Thomas Williams was sent to De Soto Point with 3,200 men to dig a canal capable of bypassing the strong defenses around Vicksburg. Despite being assisted by locally enslaved people, Williams was unable to finish constructing the canal due to disease and falling river levels, and the project was abandoned until January 1863, when Union Major-General Ulysses S. Grant took an interest in the project.

Grant attempted to resolve some of the issues inherent to the concept by moving the upstream entrance to a spot with a stronger current, but the heavy rains and flooding that broke a dam prevented the project from succeeding. Work was abandoned in March, and Grant eventually used other methods to capture Vicksburg, whose Confederate garrison surrendered on July 4, 1863. In 1876, the Mississippi River changed course to cut across De Soto Point, eventually isolating Vicksburg from the river, but the completion of the Yazoo Diversion Canal in 1903 restored Vicksburg's river access. Most of the canal site has since been destroyed by agriculture, but a small section survives. This section was donated by local landowners to the National Park Service and became part of Vicksburg National Military Park in 1990. A 1974 article in The Military Engineer speculated that the canal would likely have been successful if the dam at the downstream end of the canal had been opened.

History

Background

During the opening days of the American Civil War in 1861, Winfield Scott, Commanding General of the United States Army, developed the Anaconda Plan for defeating the Confederate States of America. A major part of this plan was controlling the Mississippi River, to cut the Confederacy in two and provide a supply outlet for northern goods to reach foreign markets.[1] In early 1862, the Union Army defeated Confederate forces in several significant battles, including Shiloh, First Corinth, Fort Donelson, and Island Number Ten. The city of New Orleans also fell to Union troops in late April. Between the capture of New Orleans and the battlefield victories, much of the Mississippi Valley was in Union hands.[2] Flag Officer David Farragut commanded the Union Navy elements which had been present at New Orleans, and took his ships upriver to the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi,[3] which was considered to be strategically valuable as it connected the regions west of the Mississippi River with the eastern portions of the Confederacy.[4] The naval force was accompanied by 1,500 Union troops under the command of Brigadier-General Thomas Williams.[5] After reaching Vicksburg in mid-May, Farragut unsuccessfully demanded that the city surrender to his fleet. On May 20, the first Union shot towards Vicksburg was fired by USS Oneida, and more bombardments followed on May 26 and 28 before Farragut decided to fall back to New Orleans, a move that was politically unpopular.[3] The decision to withdraw was the result of falling river levels threatening to strand the Union ships, a shortage of coal, and Farragut being ill.[6]

Another attempt on the city was made in June. Williams again accompanied the expedition, this time with a 3,200-man force. Williams's infantrymen, Farragut's fleet, and a group of ships armed with mortars commanded by Commodore David Dixon Porter left the city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on June 20. They reached Vicksburg five days later.[7] On June 26, Porter and Farragut's ships attempted to bombard the Confederate artillery batteries defending the city, but were unable to do so. Confederate counter-battery fire was ineffective due to most Union ships anchoring out of range of the Confederate guns, and the remainder being anchored in a location shielded by heavy vegetation.[8] Two days later, Farragut ordered most of his ships (but not Porter's) to pass in front of the city's defenses to meet a fleet of Union ironclads that had traveled down the river from Memphis, Tennessee. Farragut's movement involved navigating around De Soto Point, a peninsula of land on the Louisiana side of the river, where the Mississippi River made a horseshoe-shaped meander. The Union ships suffered damage, but were able to pass the batteries.[9] Farragut and the commander of the ironclads, Flag Officer Charles Davis, agreed that the Union Navy could not capture the city without large numbers of army troops and that the needed number of infantrymen would not be released by the Union general-in-chief, Major-General Henry Halleck, for the Vicksburg operations.[10]

1862 attempt

In 1853, as part of his survey of the Mississippi River for the Secretary of War, engineer Charles Ellet Jr. determined that the Mississippi was likely to cut across the narrow De Soto Point, leaving Vicksburg isolated on an oxbow lake.[11] On June 6, 1862, the idea of cutting a canal across the point had been referenced in communication between Williams and Major-General Benjamin Butler.[12] Williams selected a site for a canal to be built across the point in early June,[13] and his men began digging on June 27, assisted by 1,200 local slaves, most of whom were from nearby plantations.[14] These slaves had been impressed into service by Union raiding parties, although many had come willingly, having been told that they would be freed for their work. Williams intended to free them only if the canal was completed successfully and treated them harshly.[15] As planned, the canal would have openings on the river 6 miles (10 km) upstream and 3.5 miles (6 km) downstream from Vicksburg.[16] The canal's length was to be 1.25 miles (2 km)[14] or 1.33 miles (2 km)[13] with a width of 50 feet (20 m) and depth of 13 feet (4 m).[14][16] While the path of the canal could conceivably have been as short as 0.75 miles (1 km), the longer route was chosen to stay further from Vicksburg's defenses.[17]

If the plan worked as intended, the Mississippi would cut through the canal ditch, allowing Union ships to traverse the river without being fired on by the defenders of Vicksburg. It was also considered possible that the river would move from its old course through the canal cut, isolating Vicksburg from the river entirely.[16] Progress was hampered by the falling level of the river and outbreaks of disease.[18] Williams's soldiers were primarily men from New England who were unused to the climate of southern summers.[12] The temperature in the area sometimes reached as high as 110 °F (40 °C), potable water was scarce, and the mosquito-ridden swamps in the area were havens for disease. Malaria, dysentery, and scurvy were common among the workers, and supplies of quinine to treat malaria ran out. Disease was further promoted by soldiers dumping raw sewage into the Mississippi River, which was also their source of drinking water.[19]

The geology of the ground where the canal was dug was thought to consist of about 11 feet (3 m) of clay with sand below.[20][a] A river current was expected to cut through the sand, but not the clay, so the clay needed to be entirely removed before the canal was opened to the river.[20][b] The river was falling almost 1 foot (0.3 m) a day, although reports from upriver at St. Louis noted that the Mississippi was rising further north. This rise did not manifest itself downstream where the canal project was.[18] A rise in the river's level was expected in June, but this never happened.[21] By July 4, 1862, the cut was only about 7 feet (2 m) deep.[20] A week later, the depth of the canal was 1.5 feet (0.5 m) below the surface level of the river.[21] Williams considered opening the canal to the river at this time, but was delayed by soil collapses in the canal. By the time this was resolved, the river had fallen to below the trough of the canal.[22] On July 17 the canal had a depth of 13 feet (4 m) and a width of 18 feet (5 m).[21] A steamboat was set up near the opening of the canal in a failed attempt to force water into the canal.[23] The workers dug even deeper, but the walls of the canal collapsed in several places.[14]

As the conditions deteriorated further, Williams decided that the canal was no longer feasible and ordered his men from De Soto Point, ending work on July 24.[24][25] In addition to the problems at the canal site, the Confederates were showing signs of activity in the Baton Rouge area and near the Red River.[22] His command had been reduced by disease to 700[26] or 800 healthy soldiers.[25] The civilian workers suffered from sickness as well.[26] With the withdrawal of the infantrymen being at least part of his decision, Davis withdrew his ironclads upriver to Helena, Arkansas.[25] Farragut's ships also withdrew at this time, escorting the transports carrying Williams's infantrymen back to Baton Rouge. These deep-draft naval vessels moved downstream with difficulty.[27] When the Confederate States Army later examined the area where the canal construction had taken place, they found 600 graves and 500 abandoned African Americans,[25] most of whom were ill. The other African-American slaves had been either forcibly returned to their owners, or given three days's rations and instructions to walk back to their homes.[28] The ditch had reached a depth of 13 feet (4 m) and was 18 feet (5 m) wide, but these dimensions were not enough to allow navigation[24] because the river level had fallen below the ditch's trough.[21] Although the proposed bypass of Vicksburg had failed, the diggers did destroy part of the Vicksburg, Shreveport and Texas Railroad, severing an important Confederate rail connection across the Mississippi.[29]

1863 attempt

In late November 1862, Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant began an offensive aimed at Vicksburg. He took 40,000 soldiers into northern Mississippi while Major-General William T. Sherman made an amphibious thrust down the Mississippi towards Vicksburg. Both wings were forced to withdraw, Grant's after his supply line was wrecked by the Holly Springs Raid and West Tennessee Raids and Sherman's after a repulse at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou.[30] Sherman's men fell back to Milliken's Bend, Louisiana, Sherman being superseded in command by Major-General John McClernand. The two generals took the force north to Arkansas Post, Arkansas, and captured a Confederate fort in early January in the Battle of Arkansas Post. Grant then ordered Sherman to take a force down to the old canal site and resume work on the project.[31] Overall command of the move against Vicksburg was taken over by Grant in late January 1863, although the lead elements of his force had already reached the area.[32] A direct attack on Vicksburg was impractical; the strength of the Confederate defenses had been improved since Farragut's campaign the previous year, the terrain north of the city in the Mississippi Delta was impassable to an army, and a withdrawal to Memphis to make a second overland attempt would be publicly viewed as a defeat and would be politically disastrous.[33]

Despite some urging from a Vicksburg newspaper editor, Confederate troops had never filled in the traces of the canal. The steamboat Catahoula was sent to the area in January 1863 by the Union, under the command of a Lieutenant Wilson, to scout the remains of the canal cut. Both the captain of the vessel and a newspaperman on board reported that while there was water standing in the canal, it was stagnant and that the cut needed significant work before large ships such as Union Navy ironclads could pass through it.[34] Union Colonel Josiah W. Bissell, who had prior engineering experience, surveyed the canal on January 10 and noted that it was still in similar shape as to how Williams left it. All of the previously excavated dirt had been thrown to the side facing Vicksburg, which provided some protection from Confederate fire and made it easier to widen the canal, as the side to be widened did not contain excess debris.[35] During the new round of digging, some of the dirt from the side facing Vicksburg was removed and the western side of the widened canal built up, to encourage floodwaters to flow east, away from the Union camps.[36] Although he was initially unconvinced by the project,[37] Grant ordered that the digging resume after making some adjustments to the plans of the canal.[38] Visiting Union officers later found that the water was only 2 feet (0.6 m) in the ditch and also noted the lack of a current,[39] although depths of up to 8 feet (2 m) and widths up to 12 feet (4 m) were also reported.[40] Tree stumps would need to be removed from the canal sides and a levee would need to be constructed to prevent canal water from flooding into where Union camps would be located.[41]

The project had the support of President Abraham Lincoln.[42] The first workers were assigned to the canal project on January 23.[43] Major-General Carter L. Stevenson, the immediate Confederate commander of the Vicksburg defenses, originally interpreted the Union movement to the canal site as preparatory to cross the river at Warrenton, Mississippi. However, the Confederate regional commander, Lieutenant-General John C. Pemberton doubted a crossing would be attempted, and learned of the true Union plan the next day from papers captured along with the mortally wounded commander of the 15th Illinois Cavalry Regiment.[44] The canal was widened to 16 feet (5 m) within a week, but because there was water in the canal, the newly widened points only had a depth down to the water level.[40][43] The use of dredging boats would have been a solution to this problem, but none were available at the time.[45] Water depth was increased to 5 feet (2 m), and in hopes of creating greater erosion in the canal, soldiers were ordered to dig pits along its sides.[43] Another attempt to use a steamboat to push water into the canal was made, but again failed. By the end of the month, Grant was beginning to think that the canal project would not succeed, but continued with the construction.[46] Captain Frederick E. Prime was placed in command of the effort on January 28.[45] Outbreaks of disease struck again, and the levees around the project frequently broke, flooding parts of the canal.[47] At least some of this flooding was caused by intentional levee damage by Confederate troops, and the flooding led to the Union camps along the southern portion of the canal having to be relocated.[48] The diggers were also exposed to Confederate artillery fire. By now, the construction had been divided into 160-foot (50 m) sections, with the intention of making each section 6 feet (2 m) deep and 60 feet (20 m) wide.[47] As these early attempts at working on the canal failed to achieve significant progress, Grant ordered that the upstream end of the canal be moved to a point 200 yards (200 m) upstream to allow for a stronger current to flow into the ditch;[45][49] it had been found that Williams selected a poor location for the canal opening.[50]

Rains hampered the project by exposing poorly buried graves from the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou and turning the soil to a consistency Sherman described as "wet, almost water".[38] Union morale was falling, the work was inefficient, and Grant banned gambling and the sale of alcohol.[51] Prime determined that the only way to deepen the canal would be to drain it, so he ordered any holes in the levees surrounding the canal plugged with dirt-filled gunny sacks. This process was completed by February 9, although it was noted that evidence of current-based erosion was finally sighted shortly before the canal was closed off. By February 12, the new entrance, which was constructed by 550 African Americans, had dimensions of 60 feet (20 m) across and 4 feet (1 m) deep. Water still kept rising through February 16, so one of the levees closing the canal off from the campsites was opened to drain the excess water into an unused area.[52] On the 19th, a steam-powered sump pump was completed; the sump itself had been completed ten days earlier. That same day, 1,000 African American laborers were sent from Memphis to work on the project.[53] In mid-February, the work assignments were rearranged so that each regiment had a 150-yard (100 m) section. The regiments were in turn subdivided so that an individual soldier only worked on the canal for two hours a day; units competed against each other in the construction work. Though many soldiers were theoretically available to work on the project, only 3,000 or 4,000 were assigned to it due to lack of tools.[54][55] About 2,000 civilian laborers also worked on the canal during the life of the project.[55] Two dredging boats were finally secured on February 16, the first arriving on March 1.[56]

Union newspapers criticized the project, and the Confederates built new artillery emplacements capable of enfilading most of the canal.[38] Optimism among those working on the canal grew as progress was made. Grant sent a message to Halleck on March 4 stating that the canal was only days from completion, and the second dredging boat arrived the next day.[57] On March 7, the dam holding the upstream end of the canal failed, inundating the canal.[40] The opening in the levee expanded until it was 150 feet (50 m) wide, and water flooded some of the Union campsites.[57] This breach was a disaster for the project. Though the inflow of water had flooded the area, it had not produced any scouring effect.[58] Prime ordered the lower end of the canal blown and attempted to plug the upper breach with a coal barge.[59] The attempt to use the coal barge failed, as the engineers lost control of the barge and it damaged one of the dredging boats.[60] It took days of frantic work to plug the hole.[59] By March 12, the upper half of the canal only needed some widening and stump and tree removal, while the lower half required little widening but still some stump removal. Aside from those issues, the only remaining work to be done was filling a breach in one of the canal's side levees.[61] The flooding had caused the cut to begin to fill with sediment, and the two dredging boats, Hercules and Sampson, were sent to try to clear the channel, but they came under Confederate artillery fire.[24][40] With the soldiers flooded out and forced to higher ground elsewhere, the dredges continued the work.[62] By March 19, Confederate fire had become accurate enough that the dredges could only operate under the cover of night.[63] Grant wrote on March 22 that he doubted that the canal would be useful, and noted that Confederate artillery had been positioned to fire down the exit end of the canal.[63] The dredges were withdrawn two days later.[63] Their civilian operators had balked at working under enemy fire, stating that being shot at was not part of their contract.[62] On March 27, Halleck was informed that the project had ended.[62] Grant's canal had been a failure.[64] The canal had reached a width of about 60 feet (20 m) and a depth of about 9 feet (3 m) to 12 feet (4 m).[40] Grant viewed the canal construction as a good way to prevent idleness among his soldiers, but eventually conceived another way to get troops past Vicksburg.[65] In Sherman's words, the canal was "labor lost".[66]

Aftermath

A similar attempt, known as the Duckport Canal, was made 3 miles (5 km) to the north. Near Duckport, Louisiana, a 1 mile (2 km) channel that was 40 feet (10 m) wide and 7 feet (2 m) deep was to be dug to connect the Mississippi to Walnut Bayou. It was hoped that this would provide a navigable channel to the Mississippi at New Carthage, Louisiana, downstream from Vicksburg. On April 13, a levee was blasted to open the channel, but Grant decided that the project would take too long to be viable, although the work still continued with hopes of using the Duckport cut as a future supply channel. The transport Silver Wave attempted to navigate the lower part of the path, but was unable to do so because of low water and submerged trees obstructing the path. The Mississippi began to fall, and low waters doomed the Duckport Canal; by April 27, there was only 6 inches (20 cm) of water where the cut entered Walnut Bayou.[67] Another digging project was made with the Lake Providence Canal. Located 40 miles (64 km) to the north of Vicksburg, the Lake Providence project was intended to produce a water route into the Red River, and bypass Vicksburg that way. Work began on it while the canal at De Soto Point was still being worked on; the Lake Providence cut was expected to be much easier. Union troops cut levees on March 4 and 17, but the project encountered difficulties with trees blocking the path, and Grant had the attention given there redirected elsewhere before a needed sawing machine arrived.[68] Other failed attempts to get around Vicksburg were the Steele's Bayou Expedition and the Yazoo Pass Expedition, two attempts to weave through the waterways to the north of the city.[69]

Grant decided to land troops on the Mississippi side of the river below Vicksburg in April.[70] After pushing aside Confederate resistance at the battles of Port Gibson and Raymond, Grant's soldiers moved against Jackson, Mississippi, and captured the city from a Confederate army assembled to support Vicksburg. The Confederate defenders of Vicksburg had moved east from the city but were defeated at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16. By May 18, Grant's men had reached Vicksburg. Frontal attacks against the city on May 19 and 22 failed with significant losses, and the city was placed under siege. The siege of Vicksburg continued until the Confederate defenders surrendered on July 4. After Vicksburg surrendered, the Confederate garrison of Port Hudson, Louisiana, followed suit, giving the Union full control of the Mississippi River.[71] The fall of Vicksburg was a decisive blow to the Confederacy and directly contributed to the eventual Confederate defeat.[72]

In April 1876, the Mississippi River changed course, cutting through De Soto Point and eventually isolating Vicksburg from the riverfront after the oxbow lake formed by the course change became cut off from the river. Vicksburg would not be a river town again until the completion of the Yazoo Diversion Canal in 1903.[73] The natural path was only about 1.5 miles (2 km) away from where Grant's Canal had been attempted.[74] Most of the canal path has since been destroyed by agriculture, but a small section still remains. The owners of the tract donated it to the National Park Service and it was added to Vicksburg National Military Park in 1990. Union African American soldiers who fought at the battles of Milliken's Bend and Goodrich's Landing are also commemorated at the site. A monument to the 9th Connecticut Infantry Regiment was also dedicated at the site in 2008.[24] The National Park Service unit is located in Madison Parish, Louisiana.[75]

Assessment

The historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel suggest that by the end of the project, Grant was only continuing the canal to please project supporter Lincoln and to distract the Confederates.[55] At the time of the 1863 attempt, Grant was not particularly popular in the Union, and newspaperman Sylvanus Cadwallader wrote that he believed Grant could only keep his command by occupying his soldiers with activity. Some outside observers did view Grant's Canal as the best option for taking the city, and it received press attention in the Union, Confederacy, and Europe.[76] Ed Bearss describes Grant's canal efforts as showing his willingness to try any available opportunity.[77] Likewise, the historian Shelby Foote included the canal as one of seven different failed attempts made before Grant successfully took Vicksburg.[78] A 1974 article published in The Military Engineer calculated that if the dam at the downstream end of the canal had been opened along with the breach in the upper canal, then a current strong enough to successfully erode through the canal cut would have probably been produced.[40] Writer Kevin Dougherty believes that Grant's willingness to try various projects to get around the city had a side effect of confusing the Confederates.[79] Engineer David F. Bastian suggests that the canal came close to success, and could have been successful if dredges had been obtained in January instead of March. He believes that using the dredges would have been more effective at widening and deepening the ditch than manual labor, and would have been less affected by rising river levels. The project would also have been completed quicker, allowing for time to reroute the downstream end of the canal away from the new Confederate batteries. If successful, the canal could have rendered Vicksburg moot by bypassing it. Historical consensus has nonetheless treated the project as impractical.[74]

See also

- Dutch Gap, a similar attempt in 1864 on the James River.

Notes

References

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b "The Long, Gruesome Fight to Capture Vicksburg". American Battlefield Trust. July 29, 2013. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 120, 128.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 128.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 135–137.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 148–149, 152.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 92, 153.

- ^ Bastian 1995, p. 3.

- ^ a b Smith 2023, p. 84.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Winschel, Terry (September 2, 2016). "Engineers at Vicksburg: Part Four, Grant's Canal". Targeted News Service. ProQuest 1816225668. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b c Carter 1980, p. 63.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 154–156.

- ^ a b c Miller 2019, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d e f Bastian 1974, p. 228.

- ^ a b Smith 2023, p. 85.

- ^ Bastian 1995, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d "Grant's Canal". National Park Service. October 25, 2018. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ballard 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 154, 156–157.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 256–259.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Carter 1980, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Bastian 1995, p. 27.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 107.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Carter 1980, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d e f Bastian 1974, p. 229.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Bastian 1995, p. 30.

- ^ Smith 2023, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b c Bastian 1995, p. 33.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 30, 33.

- ^ a b Ballard 2004, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Smith 2023, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 110.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 111.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 36, 38.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 38, 41–42.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 38, 41.

- ^ a b c Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, pp. 42, 44.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 195.

- ^ Bastian 1995, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Miller 2019, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Bastian 1995, p. 45.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Carter 1980, p. 113.

- ^ Foote 1986, p. 192.

- ^ Bastian 1995, pp. 46, 49.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, p. 30.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 158–173.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 482–483.

- ^ "Water Returned to City's Doorstep 100 Years Ago". Vicksburg Post. January 27, 2003. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Bastian 1995, p. 52.

- ^ "Vicksburg National Military Park Expansion: Grant's Canal". National Park Service. December 18, 2017. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 270.

- ^ Bearss 2007, p. 204.

- ^ Foote 1995, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, p. 90.

Sources

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2893-9.

- Bastian, David Fenwick (July–August 1974). "Hydraulic Analysis of Grant's Canal". The Military Engineer. 66 (432): 228–229. JSTOR 44558356. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- Bastian, David F. (1995). Grant's Canal: The Union Attempt to Bypass Vicksburg. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: Burd Street Press. ISBN 0-942597-93-1.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (2007) [2006]. Fields of Honor. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- Carter, Samuel (1980). The Final Fortress: The Campaign for Vicksburg 1862–1863. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3128-3926-0.

- Dougherty, Kevin (2011). The Campaigns for Vicksburg 1862–1863: Leadership Lessons. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-014-5.

- Foote, Shelby (1995) [1963]. The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign (Modern Library ed.). New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60170-8.

- Foote, Shelby (1986) [1963]. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-74621-X.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2023). Bayou Battles for Vicksburg: The Swamp and River Expeditions, January 1–April 30, 1863. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3566-5.