Grottasöngr

Grottasǫngr (or Gróttasǫngr; Old Norse: 'The Mill's Songs',[1] or 'Song of Grótti') is an Old Norse poem, sometimes counted among the poems of the Poetic Edda as it appears in manuscripts that are later than the Codex Regius. The tradition is also preserved in one of the manuscripts of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda along with some explanation of its context.

The myth has also survived independently in modified forms in northern European folklore. Gróttasǫngr had social and political impact in Sweden during the 20th century as it was modernized in the form of Den nya Grottesången by Viktor Rydberg, which described conditions in factories using the mill of Grottasǫngr as a literary backdrop.

Poetic Edda

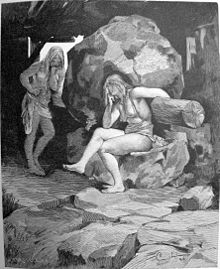

Though not originally included in the Codex Regius, Gróttasǫngr is included in many later editions of the Poetic Edda.[2] Gróttasǫngr is the work song of two young slave girls bought in Sweden by the Danish King Frodi (cf. Fróði in the Prose Edda). The girls are brought to a magic grindstone to grind out wealth for the king and sing for his household.

The girls ask for rest from the grinding but are commanded to continue. Undaunted in their benevolence, the girls proceed to grind and sing, wishing wealth and happiness for the King. The King, however, is still not pleased and continues to order the girls to grind without interruption.

King Frodi is ignorant of their lineage and the girls reveal that they are descended from mountain-risar. The girls recount their past deeds, including moving a flat-topped mountain and revealing that they had actually created the grinding stone they are now chained to. They tell him that they had advanced against an army in Sweden and fought "bearlike warriors",[3] had "broken shields",[3] supported troops, and overthrown one prince while supporting another. They recount that they had become well known warriors.

The girls then reflect that they have now become cold and dirty slaves, relentlessly worked, and living a life of dull grinding. The girls sing that they are tired, and call to King Frodi to wake up so that he may hear them. They announce that an army is approaching, that Frodi will lose the wealth they've ground for him, that he will also lose the magic grindstone, and that the army will burn the settlement and overthrow Frodi's throne in Lejre. They are grinding this army into existence via the magic stone. They then comment that they are "not yet warmed by the blood of slaughtered men".[3]

The girls continue to grind even harder and the shafts of the mill-frame snap. They then sing a prophecy of vengeance mentioning Hrólfr Kraki, Yrsa, Fróði and Halfdan:

Mölum enn framar. |

Let us grind on! |

Now filled with a great rage, the girls grind even harder until finally the grinding mechanism collapses and the magical stone splits in two. With the impending army soon to arrive, one of the girls finishes the song with:

Frodi, we have ground to the point where we must stop,

now the ladies have had a full stint of milling![3]

Prose Edda

Snorri relates in the Prose Edda that Skjöldr ruled the country that we today call Denmark. Skjöldr had a son named Friðleifr who succeeded him on the throne. Friðleifr had a son who was named Fróði who became king after Friðleifr, and this was at the time when Caesar Augustus proclaimed peace on earth and the Christian figure Jesus was born. The same peace ruled in Scandinavia, but there it was called Fróði's peace. The North was so peaceful that no man hurt another, even if he met his father's or his brother's killer, free or tied. No man was a robber and a golden ring could rest on the moor of Jelling for a long time.

King Fróði visited Sweden and its king Fjölnir, and from Fjölnir he bought two enslaved gýgjar named Fenja and Menja who were big and strong. In Denmark, there was a pair of magical mill stones; the man who ground with them could ask them to produce anything he wished. However, they were so big that no man was strong enough to use them. This mill was called "Grótti" and it had been given to Fróði by Hengikjopt.

Fróði had Fenja and Menja tied to the mill and asked them to grind gold, peace and happiness for himself. Then he gave them neither rest nor sleep longer than the time of a song or the silence of the cuckoo. In revenge Fenja and Menja started to sing a song named the "song of Grótti" (the poem itself) and before they ended it, they had produced a host led by a sea-king named Mysing. Mysing attacked Fróði during the night, killed him, and left with rich booty. This was the end of the Fróði peace.

Mysing took Grótti as well as Fenja and Menja and asked them to grind salt. At midnight, they asked Mysing if he did not have salt enough, but he asked them to grind more. They only ground for a short while before the ships sank. A giant whirlpool (maelstrom from mal "mill" and ström "stream") was formed as the sea started rushing through the center of the mill stone. Then the sea begun turning salt.

Post-Christianisation folklore

Modified forms of the tale are found as stories such as Why the Sea Is Salt, collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe in their Norske Folkeeventyr.

In Orcadian and Shetlandic folklore, the gýgjar are renamed 'Grotti Finnie' and 'Grotti Minnie' who are two witches that create a whirlpool in the Pentland Firth, named the Swelkie.[5]

Modern cultural references

Viktor Rydberg's apprehension of unregulated capitalism at the dawn of the industrial age is most fully expressed in his acclaimed poem Den nya Grottesången (The New Grotti Song) in which he delivered a fierce attack on the miserable working conditions in factories of the era, using the mill of Grottasöngr as his literary backdrop.[6]

Grottasǫngr appears as part of Johannes V. Jensen's novel The Fall of the King.[7] The author edited his prose text into a prose poem that was included in his first poetry collection published in 1906. Jensen later reflected on the Grottasǫngr in his book Kvinden i Sagatiden.[8]

The Raven Tower by Ann Leckie also draws inspiration from the Grottasǫngr in the character of the Strength and Patience of the Hill.[9]

Verses of the poem were used for the song Grótti by French neofolk group Skáld in 2020.[10]

References

- ^ Orchard 1997, p. 63.

- ^ 1907 edition of the Nordisk familjebok. Viewable online via Project Runeberg at https://runeberg.org/nfbf/0715.html

- ^ a b c d Larrington, Carolyne. The Poetic Edda: A new translation by Carolyne Larrington (1996) ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- ^ "Gróttasǫngr: The Lay of Grótti, or The Mill_Song". Northvegr Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ Marwick, Ernest W. (1975). The folklore of Orkney and Shetland. London: B.T. Batsford. p. 32. ISBN 0713429992.

- ^ Kunitz & Colby (1967), p. 810

- ^ Erik Svendsen (2009). "Grottesangen i Johannes V. Jensens og Viktor Rydbergs regi" (PDF). Danske Studier (in Danish): 177–180. ISSN 0106-4525. Wikidata Q62388510.

- ^ Johannes V. Jensen (1942), Kvinden i Sagatiden (in Danish), Illustrator: Aage Sikker Hansen, Johan Thomas Lundbye, Copenhagen: Gyldendal, Wikidata Q62388417

- ^ "360. ANN LECKIE (A.K.A. SINGULARITRIX) — THE RAVEN TOWER (AN INTERVIEW)". The Skiffy and Fanty Show (Podcast). 16 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Grótti, 2020-10-09, retrieved 2022-06-26

Bibliography

- Kunitz, Stanley J.; Colby, Vineta, eds. (1967). "Rydberg, (Abraham) Viktor". European Authors 1000–1900. New York, NY: H. W. Wilson Co. ISBN 9780824200138.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-34520-5.

- Tolley, Clive (ed. and trans.), Gróttasǫngr: The Song of Grotti. Viking Society for Northern Research, 2008.

External links

- Gróttasǫngr in Old Norse

- Den nya Grottesången in Swedish from «Kulturformidlingen norrøne tekster og kvad» Norway.