Empress Jingū

| Empress Jingū 神功皇后 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

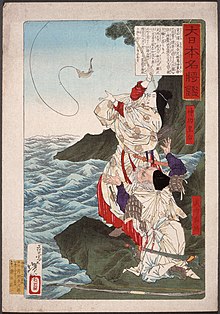

Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1843-44 | |||||

| Empress of Japan | |||||

| Reign | 201–269[1] (de facto)[a] | ||||

| Predecessor | Chūai (traditional) | ||||

| Successor | Ōjin (traditional) | ||||

| Empress consort of Japan | |||||

| Tenure | 192–200 | ||||

| Born | 169[2] | ||||

| Died | 269 (aged 100) (Kojiki)[3] | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Emperor Chūai | ||||

| Issue | Emperor Ōjin | ||||

| |||||

| House | Imperial House of Japan | ||||

| Father | Okinaga no Sukune | ||||

Empress Jingū (神功皇后, Jingū-kōgō)[b] was a legendary Japanese empress who ruled as a regent following her husband's death in 200 AD.[5][6] Both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki (collectively known as the Kiki) record events that took place during Jingū's alleged lifetime. Legends say that after seeking revenge on the people who murdered her husband, she then turned her attention to a "promised land." Jingū is thus considered to be a controversial monarch by historians in terms of her alleged invasion of the Korean Peninsula. This was in turn possibly used as justification for imperial expansion during the Meiji period. The records state that Jingū gave birth to a baby boy whom she named Homutawake three years after he was conceived by her late husband.

Jingū's reign is conventionally considered to have been from 201 to 269 AD, and was considered to be the 15th Japanese imperial ruler until the Meiji period.[c] Modern historians have come to the conclusion that the name "Jingū" was used by later generations to describe this legendary Empress. It has also been proposed that Jingū actually reigned later than she is attested. While the location of Jingū's grave (if any) is unknown, she is traditionally venerated at a kofun and at a shrine. It is accepted today that Empress Jingū reigned as a regent until her son became Emperor Ōjin upon her death. She was additionally the last de facto ruler of the Yayoi period.[d]

Legendary narrative

The Japanese have traditionally accepted this regent's historical existence, and a mausoleum (misasagi) for Jingū is currently maintained. The following information available is taken from the pseudo-historical Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, which are collectively known as Kiki (記紀) or Japanese chronicles. These chronicles include legends and myths, as well as potential historical facts that have since been exaggerated and/or distorted over time. According to extrapolations from mythology, Jingū's birth name was Okinaga-Tarashi (息長帯比売), she was born sometime in 169 AD.[2][8][9] Her father was named Okinaganosukune (息長宿禰王), and her mother Kazurakinotakanuka-hime (葛城高額媛). Her mother is noted for being a descendant of Amenohiboko (天日槍), a legendary prince of Korea (despite the fact that Amenohiboko is believed to have moved to Japan between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, at least 100 years after the extrapolated birth year of his granddaughter Jingū[10]).[11] At some point in time she wed Tarashinakahiko (or Tarashinakatsuhiko), who would later be known as Emperor Chūai and bore him one child under a now disputed set of events. Jingū would serve as "Empress consort" during Chūai's reign until his death in 200 AD.

Emperor Chūai died in 200 AD, having been killed directly or indirectly in battle by rebel forces. Okinagatarashi-hime no Mikoto then turned her rage on the rebels whom she vanquished in a fit of revenge.[8] She led an army in an invasion of a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the Korean Peninsula), and returned to Japan victorious after three years.[12] While returning to Japan she was nearly shipwrecked but managed to survive thanks to praying to Watatsumi, and she made the shrine to honor him.[13] Ikasuri Shrine and Ikuta Shrine and Watatsumi Shrine were both also made at the same time by the Empress.[13] She then ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne as Empress Jingū, and legend continues by saying that her son was conceived but unborn when Chūai died.[13]

According to a certain source Empress Jingu had sex with the god Azumi-no-isora while pregnant with Emperor Ojin after he said from the womb that it was acceptable, and then Azumi no Isora gave her the tide jewels, and she later strapped a stone to her stomach to delay the birth of her son.[14]: xxvii [e] After those three years she gave birth to a baby boy whom she named Homutawake.

The narrative of Empress Jingū invading and conquering the Korean Peninsula is now considered controversial and up for debate due to the complete lack of evidence and involvement of both the Japanese and Korean points of view. According to the Nihon Shoki, the king of Baekje gifted Jingū a Seven-Branched Sword sometime in 253 AD.[18][f] Empress Jingū was the de facto ruler until her death in 269 at the age of 100.[1][3] The modern traditional view is that Chūai's son (Homutawake) became the next Emperor after Jingū acted as a regent. She would have been de facto ruler in the interim.[1]

Known information

Empress consort Jingū is regarded by historians as a legendary figure, as there is insufficient material available for further verification and study. The lack of this information has made her very existence open to debate. If Empress Jingū was an actual figure, investigations of her tomb suggest she may have been a regent in the late 4th century AD or late 5th century AD.[19][20][page needed]

There is no evidence to suggest that the title tennō was used during the time to which Jingū's regency has been assigned. It is certainly possible that she was a chieftain or local clan leader, and that the polity she ruled would have only encompassed a small portion of modern-day Japan. The name Jingū was more than likely assigned to her posthumously by later generations; during her lifetime she would have been called Okinaga-Tarashi respectively.[8] Empress Jingū was later removed from the imperial lineage during the reign of Emperor Meiji as a way of making sure the lineage remained unbroken. This occurred when examining the emperors of the Northern Court and Southern Court of the fourteenth century. Focus was given on who should be the "true" ancestors of those who occupied the throne.[21]

Gosashi kofun

While the actual site of Jingū's grave is not known, this regent is traditionally venerated at a kofun-type Imperial tomb in Nara.[22] This kofun is also known as the "Gosashi tomb", and is managed by the Imperial Household Agency. The tomb was restricted from archaeology studies in 1976 as the tomb dates back to the founding of a central Japanese state under imperial rule. The Imperial Household Agency had also cited "tranquility and dignity" concerns in making their decision. Serious ethics concerns had been raised in 2000 after a massive archaeological hoax was exposed. Things changed in 2008 when Japan allowed limited access to Jingū's kofun to foreign archaeologists, who were able to determine that the tomb likely dated to the 4th century AD. The examination also discovered haniwa terracotta figures.[19][4][23] Empress Jingū is also enshrined at Sumiyoshi-taisha in Osaka, which was established in the 11th year of her reign (211 AD).[24]

Controversy

Birth of Ōjin and Jingū's Identity

According to the Kiki, Empress Jingū gave birth to a baby boy whom she named Homutawake (aka Emperor Ōjin) following her return from Korean conquest. The legend alleges that her son was conceived but unborn when Emperor Chūai died. As three more years would pass before Homutawake was finally born, this claim appears to be mythical and symbolic rather than real. Scholar William George Aston has suggested that this claim was misinterpreted, and instead refers to a period of less than nine months containing three "years" (some seasons), e.g. three harvests.[25] If Ōjin was an actual historical figure then historians have proposed that he ruled later than attested years of 270 to 310 AD.[19][26][27]

Jingū's identity has since been questioned by medieval and modern scholars whom have put forward different theories. Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293–1354) and Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725) asserted that she was actually the shaman-queen Himiko.[28] The kiki does not include any mentions of Queen Himiko, and the circumstances under which these books were written is a matter of unending debate. Even if such a person was known to the authors of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, they may have intentionally decided not to include her.[29] However, they do include imperial-family shamans identified with her which include Jingū. Modern scholars such as Naitō Torajirō have stated that Jingū was actually Yamatohime-no-mikoto and that Wa armies obtained control of southern Korea.[30] Yamatohime-no-Mikoto supposedly founded the Ise Shrine in tribute to the sun-goddess Amaterasu. While historian Higo Kazuo suggested that she is a daughter of Emperor Kōrei (Yamatototohimomosohime-no-Mikoto).

Korean Invasion

Both the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki give accounts of how Okinaga-Tarashi (Jingū) led an army to invade a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the Korean Peninsula).[9][12] She then returned to Japan victorious after three years of conquest where she was proclaimed as Empress. The second volume of the Kojiki (中巻 or "Nakatsumaki") states that the Korean kingdom of Baekje (百済 or "Kudara") paid tribute to Japan under "Tribute from Korea".[31] The Nihon Shoki states that Jingū conquered a region in southern Korea in the 3rd century AD naming it "Mimana".[32][33] One of the main proponents of this theory was Japanese scholar Suematsu Yasukazu, who in 1949 proposed that Mimana was a Japanese colony on the Korean peninsula that existed from the 3rd until the 6th century.[33] The Chinese Book of Song of the Liu Song dynasty also allegedly notes the Japanese presence in the Korean Peninsula, while the Book of Sui says that Japan provided military support to Baekje and Silla.[34]

In 1883, a memorial stele for the tomb of King Gwanggaeto (374 – 413) of Goguryeo was discovered and hence named the Gwanggaeto Stele. An issue arose though, when the inscriptions describing events during the king's reign were found to be in bad condition with portions illegible.[35] At the center of the disagreement is the "sinmyo passage" of year 391 as it can be interpreted in multiple ways. Korean scholars maintain that it states the Goguryeo subjugated Baekje and Silla, while Japanese scholars have traditionally interpreted that Wa had at one time subjugated Baekje and Silla. The stele soon caught the interest of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, who obtained a rubbed copy from its member Kageaki Sakō in 1884. They particularly became intrigued over the passage describing the king's military campaigns for the sinmyo in 391 AD.[36] Additional research was done by some officers in the Japanese army and navy, and the rubbed copy was later published in 1889.[37] The interpretation was made by Japanese scholars at the time that the "Wa" had occupied and controlled the Korean Peninsula. The legends of Empress Jingū's conquest of Korea could have then been used by Imperial Japan as reasoning for their annexation of Korea in 1910 as "restoring" unity between the two countries. As it was, imperialists had already used this historical claim to justify expansion into the Korean Peninsula.[32]

The main issue with an invasion scenario is a lack of evidence of Jingū's rule in Korea, or the existence of Jingū as an actual historical figure. This suggests that the accounts given are either fictional or an inaccurate/misleading account of events that occurred.[38][39][40] According to the book "From Paekchae Korea to the Origin of Yamato Japan", the Japanese had misinterpreted the Gwanggaeto Stele. The Stele was a tribute to a Korean king, but because of a lack of correct punctuation, the writing can be translated in 4 different ways. This same Stele can also be interpreted as saying Korea crossed the strait and forced Japan into subjugation, depending on where the sentence is punctuated. An investigation done by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2006 suggested that the inscription could also be interpreted as "Silla and Baekje were dependent states of Yamato Japan."[41]

The imperialist reasoning for occupation eventually led to an emotional repulsion from Jingu after World War II had ended as she had symbolized Japan's nationalistic foreign policy. Historian Chizuko Allen notes that while these feelings are understandable, they are not academically justifiable.[11] The overall popularity of the Jingū theory has been declining since the 1970s due to concerns raised about available evidence.[33]

Legacy

In 1881, Empress Jingū became the first woman to be featured on a Japanese banknote. As no actual images of this legendary figure are known to exist, the representation of Jingū which was artistically contrived by Edoardo Chiossone is entirely conjectural; Chiossone used a female employee of the Government Printing Bureau as his model for Jingū.[42] This picture was also used for 1908/14 postage stamps, the first postage stamps of Japan to show a woman. A revised design by Yoshida Toyo was used for the 1924/37 Jingū design stamps. The usage of a Jingū design ended with a new stamp series in 1939.[43]

Excluding the legendary Empress Jingū, there were eight reigning empresses and their successors were most often selected from amongst the males of the paternal Imperial bloodline, which is why some conservative scholars argue that the women's reigns were temporary and that male-only succession tradition must be maintained in the 21st century.[44]

Family tree

See also

Notes

- ^ The modern view is that Jingū served as "empress dowager" in interregnum, acting as a regent.[1]

- ^ Occasionally she is given the title 天皇 tennō, signifying an empress-regnant, as opposed to kōgō, which indicates an empress-consort.

- ^ According to the traditional order of succession, hence her alternate title Jingū tennō (神功天皇)

- ^ In terms of rulers she is traditionally listed as the last of the Yayoi period. This period itself though, is traditionally dated from 300 BC to 300 AD.[7]

- ^ According to a certain source, Isora offered his navigational services in "exchange for a sexual relationship" with the empress.[15] Though "the motif of divine union between Jingu and a sea god is relatively uncommon", the notion that Azumi-no-isora obtained sexual favors from the empress is attested in shrine-foundation myth (jisha engi) document called the Rokugō kaizan Ninmmon daibosatsu hongi (六郷開山仁聞大菩薩本紀).[16] Other shrines of the cult do not promote this idea. Isora carries out the task "without any sexual compensation" in the Hachiman gudōkun attributed to a priest at the Iwashimizu Hachimangu.[17]

- ^ The Nihon Shoki mentions her "fifty-second year" of reign

- ^ There are two ways this name is transcribed: "Ika-gashiko-me" is used by Tsutomu Ujiya, while "Ika-shiko-me" is used by William George Aston.[75]

References

- ^ a b c d Kenneth Henshall (2013). Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press. p. 487. ISBN 9780810878723.

- ^ a b Sharma, Arvind (1994). Religion and Women. SUNY Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780791416907.

- ^ a b Chamberlain, Basil Hall. (1920). "[SECT. CIII.—EMPEROR CHIŪ-AI (PART IX.—HIS DEATH AND THAT OF THE EMPRESS JIN-GŌ).]".

The Empress died at the august age of one hundred.

- ^ a b McNicol, Tony (April 28, 2008). "Japanese Royal Tomb Opened to Scholars for First Time". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Shinto Shrine Agency of Ehime Prefecture". Archived from the original on 2013-12-26. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416.

- ^ Keally, Charles T. (2006-06-03). "Yayoi Culture". Japanese Archaeology. Charles T. Keally. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ a b c Brinkley, Frank (1915). A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the end of the Meiji Era. Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. pp. 88–89.

Okinaga-Tarashi.

- ^ a b Rambelli, Fabio (2018). The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: Aspects of Maritime Religion. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350062870.

- ^ Nihon Shoki, Vol.6 "天日槍對曰 僕新羅國主之子也 然聞日本國有聖皇 則以己國授弟知古而化歸之"

- ^ a b Chizuko Allen (2003). "Empress Jingū: a shamaness ruler in early Japan". Japan Forum. 15 (1): 81–98. doi:10.1080/0955580032000077748. S2CID 143770151. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "Nihon Shoki, Volume 9". Archived from the original on 2014-04-25. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Watatsumi Shrine | 海神社 |Hyogo-ken, Kobe-shi". shintoshrines. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Rambelli, F (2018). The Sea and The Sacred in Japan. Camden: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-1350062870.

- ^ Rambelli (2018), p. 77.

- ^ Rambelli (2018), p. 69.

- ^ Rambelli (2018), p. 74.

- ^ William George, Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D.697, Tuttle Publishing, 1841

- ^ a b c Keally, Charles T. "Kofun Culture". www.t-net.ne.jp. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press. 7 November 2013. ISBN 9780810878723.

- ^ Conlan, Thomas (2011). From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth Century Japan. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780199778102.

- ^ Jingū's misasagi (PDF) (map), JP: Nara shikanko, lower right, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-24, retrieved January 7, 2008.

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan, p. 424.

- ^ "歴史年表 (History of Sumiyoshi-taisha)". sumiyoshitaisha.net. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ Aston, William. (1998). Nihongi, Vol. 1, pp. 224–253.

- ^ Jestice, Phyllis G. (2004). Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, Volumes 1-3. ABC-CLIO. p. 653. ISBN 9781576073551.

- ^ Wakabayashi, Tadashi (1995). Japanese loyalism reconstrued. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780824816674.

- ^ Mason, Penelope (2005). History of Japanese Art Second Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 29. ISBN 9780131176027.

- ^ Miller, Laura (2014). "Rebranding Himiko, the Shaman Queen of Ancient History". Mechademia. 9. University of Minnesota Press: 179–198. doi:10.1353/mec.2014.0015. S2CID 122601314.

- ^ Farris, William (1998). Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780824820305.

- ^ Chamberlain, Basil Hall. (1920). "[SECT. CX.—EMPEROR Ō-JIN (PART VIII.—TRIBUTE FROM KOREA).]".

- ^ a b Seth, Michael J. (2006). A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period Through the Nineteenth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 31. ISBN 9780742540057.

- ^ a b c Joanna Rurarz (2014). Historia Korei (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog. p. 89. ISBN 9788363778866.

- ^ Chinese History Record Book of Sui: 隋書 東夷伝 第81巻列伝46 : 新羅、百濟皆以倭為大國,多珍物,並敬仰之,恆通使往來.

- ^ Rawski, Evelyn S. (2015). Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 9781316300350.

- ^ Xu, Jianxin. 好太王碑拓本の研究 (An Investigation of Rubbings from the Stele of Haotai Wang). Tokyodo Shuppan, 2006. ISBN 978-4-490-20569-5.

- ^ Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Park Jinhoon; Yi Huyn-hae (2014), Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press, p. 49, ISBN 1107098467

- ^ E. Taylor Atkins (10 July 2010). Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910–1945. University of California Press. pp. 114–117. ISBN 978-0-520-94768-9.

- ^ Kenneth B. Lee (1997). "4. Korea and Early Japan, 200 BC – 700 AD". Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 31–35. ISBN 0-275-95823-X.

- ^ Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-521-22352-0.

- ^ Xu, Jianxin. An Investigation of Rubbings from the Stele of Haotai Wang. Tokyodo Shuppan, 2006. ISBN 978-4-490-20569-5.

- ^ History, Bank of Japan, archived from the original on 2007-12-14.

- ^ 続逓信事業史 (Continued - History of Communications Business) vol. 3 郵便 (mails), ed. 郵政省 (Ministry of Postal Services), Tokyo 1963

- ^ Yoshida, Reiji. "Life in the Cloudy Imperial Fishbowl", Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Japan Times. March 27, 2007; retrieved 2013-8-22.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 104–112.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya; Tatsuya, Yumiyama (20 October 2005). "Ōkuninushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Routledge Library Editions: Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 402. ISBN 978-1-136-90376-2. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (21 April 2005). "Ōnamuchi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b The Emperor's Clans: The Way of the Descendants, Aogaki Publishing, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. Columbia University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780231049405.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (28 April 2005). "Kotoshironushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ Sendai Kuji Hongi, Book 4 (先代舊事本紀 巻第四), in Keizai Zasshisha, ed. (1898). Kokushi-taikei, vol. 7 (国史大系 第7巻). Keizai Zasshisha. pp. 243–244.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXIV.—The Wooing of the Deity-of-Eight-Thousand-Spears.

- ^ Tanigawa Ken'ichi 『日本の神々 神社と聖地 7 山陰』(新装復刊) 2000年 白水社 ISBN 978-4-560-02507-9

- ^ a b Kazuhiko, Nishioka (26 April 2005). "Isukeyorihime". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b 『神話の中のヒメたち もうひとつの古事記』p94-97「初代皇后は「神の御子」」

- ^ a b 日本人名大辞典+Plus, デジタル版. "日子八井命とは". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ^ a b ANDASSOVA, Maral (2019). "Emperor Jinmu in the Kojiki". Japan Review (32): 5–16. ISSN 0915-0986. JSTOR 26652947.

- ^ a b "Visit Kusakabeyoshimi Shrine on your trip to Takamori-machi or Japan". trips.klarna.com. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780674017535.

- ^ a b c Ponsonby-Fane, Richard (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Ponsonby Memorial Society. p. 29 & 418.

- ^ a b c Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida (1979). A Translation and Study of the Gukanshō, an Interpretative History of Japan Written in 1219. University of California Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780520034600.

- ^ 『図説 歴代天皇紀』p42-43「綏靖天皇」

- ^ a b c d e Anston, p. 144 (Vol. 1)

- ^ Grapard, Allan G. (2023-04-28). The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91036-2.

- ^ Tenri Journal of Religion. Tenri University Press. 1968.

- ^ Takano, Tomoaki; Uchimura, Hiroaki (2006). History and Festivals of the Aso Shrine. Aso Shrine, Ichinomiya, Aso City.: Aso Shrine.

- ^ Anston, p. 143 (Vol. 1)

- ^ a b c d Anston, p. 144 (Vol. 1)

- ^ Watase, Masatada [in Japanese] (1983). "Kakinomoto no Hitomaro". Nihon Koten Bungaku Daijiten 日本古典文学大辞典 (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. pp. 586–588. OCLC 11917421.

- ^ a b c Aston, William George. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697, Volume 2. The Japan Society London. pp. 150–164. ISBN 9780524053478.

- ^ a b c "Kuwashi Hime • . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史". . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ a b c Anston, p. 149 (Vol. 1)

- ^ Louis-Frédéric, "Kibitsu-hiko no Mikoto" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 513.

- ^ Ujiya, Tsutomu (1988). Nihon shoki. Grove Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8021-5058-5.

- ^ Aston, William George. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697, Volume 2. The Japan Society London. p. 109 & 149–150. ISBN 9780524053478.

- ^ a b c d Shimazu Norifumi (March 15, 2006). "Takeshiuchi no Sukune". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Asakawa, Kan'ichi (1903). The Early Institutional Life of Japan. Tokyo Shueisha. p. 140. ISBN 9780722225394.

- ^ Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida (1979). A Translation and Study of the Gukanshō, an Interpretative History of Japan Written in 1219. University of California Press. p. 248 & 253. ISBN 9780520034600.

- ^ Henshall, Kenneth (2013-11-07). Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7872-3.

- ^ "Mimakihime • . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史". . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史. Retrieved 2023-11-18.

- ^ Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida (1979). A Translation and Study of the Gukanshō, an Interpretative History of Japan Written in 1219. University of California Press. p. 248 & 253–254. ISBN 9780520034600.

- ^ a b Henshall, Kenneth (2013-11-07). Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7872-3.

- ^ "Sahobime • . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史". . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史. Retrieved 2023-11-18.

- ^ a b Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library), Issues 32-34. Toyo Bunko. 1974. p. 63. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "Yasakairihime • . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史". . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ a b Kenneth Henshall (2013). Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press. p. 487. ISBN 9780810878723.

- ^ a b Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library), Issues 32-34. Toyo Bunko. 1974. pp. 63–64. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Saigū | 國學院大學デジタルミュージアム". web.archive.org. 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ Brown Delmer et al. (1979). Gukanshō, p. 253; Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki, pp. 95-96; Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 10.

- ^ Kidder, Jonathan E. (2007). Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology. University of Hawaii Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780824830359.

- ^ a b c Packard, Jerrold M. (2000). Sons of Heaven: A Portrait of the Japanese Monarchy. FireWord Publishing, Incorporated. p. 45. ISBN 9781930782013.

- ^ a b c Xinzhong, Yao (2003). Confucianism O - Z. Taylor & Francis US. p. 467. ISBN 9780415306539.

- ^ Aston, William George. (1998). Nihongi, p. 254–271.

- ^ a b Aston, William. (1998). Nihongi, Vol. 1, pp. 224–253.

- ^ 文也 (2019-05-26). "仲姫命とはどんな人?". 歴史好きブログ (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ "日本人名大辞典+Plus - 朝日日本歴史人物事典,デジタル版 - 仲姫命(なかつひめのみこと)とは? 意味や使い方". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ "Nunasoko Nakatsuhime • . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史". . A History . . of Japan . 日本歴史. Retrieved 2023-11-18.

- ^ Aston, William. (1998). Nihongi, Vol. 1, pp. 254–271.

Further reading

- Aston, William George. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. OCLC 448337491

- Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida, eds. (1979). Gukanshō: The Future and the Past. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03460-0; OCLC 251325323

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall. (1920). The Kojiki. Read before the Asiatic Society of Japan on April 12, May 10, and June 21, 1882; reprinted, May, 1919. OCLC 1882339

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 194887

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Nihon Ōdai Ichiran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Royal Asiatic Society, Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 5850691

- Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04940-5; OCLC 59145842