Golf ball

A golf ball is a ball designed to be used in golf. Under the rules of golf, a golf ball has a mass no more than 1.620 oz (45.93 g), has a diameter not less than 1.680 inches (42.67 mm), and performs within specified velocity, distance, and symmetry limits. Like golf clubs, golf balls are subject to testing and approval by The R&A (formerly part of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews) and the United States Golf Association, and those that do not conform with regulations may not be used in competitions (Rule 5–1).

History

Early balls

It is commonly believed that hard wooden, round balls, made from hardwoods such as beech and box, were used for golf from the 14th through the 17th centuries. Though wooden balls were no doubt used for other similar contemporary stick and ball games, there is no definite evidence that they were actually used in golf in Scotland. It is equally likely, if not more so, that leather balls filled with cows' hair were used, imported from the Netherlands from at least 1486 onward.[1]

Featherie

Then or later, the featherie ball was developed and introduced. A featherie, or feathery, is a hand-sewn round leather pouch stuffed with chicken or goose feathers and coated with paint, usually white in color. A standard featherie used a gentleman's top hat full of feathers. The feathers were boiled and softened before they were stuffed into the leather pouch.[2] Making a featherie was a tedious and time-consuming process. An experienced ball maker could only make a few balls in one day, so they were expensive. A single ball would cost 2–5 shillings, which is equivalent to US$10–20 today.[3]

Guttie

In 1848, the Rev. Dr. Robert Adams Paterson (sometimes spelled Patterson) invented the gutta-percha ball (or guttie, gutty).[4][5] The guttie was made from dried sap of the Malaysian sapodilla tree. The sap had a rubber-like feel and could be made spherical by heating and shaping it in a mold. Because gutties were cheaper to produce, could be re-formed if they became out-of-round or damaged, and had improved aerodynamic qualities, they soon became the preferred ball for use.[6][7]

Accidentally, it was discovered that nicks in the guttie from normal use actually provided a ball with a more consistent ball flight than a guttie with a perfectly smooth surface. Thus, makers began intentionally making indentations into the surface of new balls using either a knife or hammer and chisel, giving the guttie a textured surface. Many patterns were tried and used. These new gutties, with protruding nubs left by carving patterned paths across the ball's surface, became known as "brambles" due to their resemblance to bramble fruit (blackberries).

Wound golf ball

The next major breakthrough in golf ball development came in 1898. Coburn Haskell of Cleveland, Ohio, had driven to nearby Akron, Ohio, for a golf date with Bertram Work, the superintendent of the B.F. Goodrich Company. While he waited in the plant for Work, Haskell picked up some rubber thread and wound it into a ball. When he bounced the ball, it flew almost to the ceiling. Work suggested Haskell put a cover on the creation, and that was the birth of the 20th-century wound golf ball that would soon replace the guttie bramble ball. The new design became known as the rubber Haskell golf ball.

For decades, the wound rubber ball consisted of a liquid-filled or solid round core that was wound with a layer of rubber thread into a larger round inner core and then covered with a thin outer shell made of balatá sap.[8] The balatá is a tree native to Central and South America and the Caribbean. The tree is tapped and the soft, viscous fluid released is a rubber-like material similar to gutta-percha, which was found to make an ideal cover for a golf ball. Balatá, however, is relatively soft. If the leading edge of a highly lofted short iron contacts a balatá-covered ball in a location other than the bottom of the ball a cut or "smile" will often be the result, rendering the ball unfit for play.

Addition of dimples

In the early 1900s, it was found that dimpling the ball provided even more control of the ball's trajectory, flight, and spin. David Stanley Froy, James McHardy, and Peter G. Fernie received a patent in 1897 for a ball with indentations;[9] Froy played in the Open in 1900 at the Old Course at St. Andrews with the first prototype.[10]

Players were able to put additional backspin on the new wound, dimpled balls when using more lofted clubs, thus inducing the ball to stop more quickly on the green. Manufacturers soon began selling various types of golf balls with various dimple patterns to improve the length, trajectory, spin, and overall "feel" characteristics of the new wound golf balls. Wound, balatá-covered golf balls were used into the late 20th century.[11]

Modern resin and polyurethane covered balls

In the mid-1960s, a new synthetic resin, an ionomer of ethylene acid named Surlyn was introduced by DuPont as were new urethane blends for golf ball covers, and these new materials soon displaced balatá as they proved more durable and more resistant to cutting.[12]

Along with various other materials that came into use to replace the rubber-wound internal sphere, golf balls came to be classified as either two-piece, three-piece, or four-piece balls, according to the number of layered components. These basic materials continue to be used in modern balls, with further advances in technology creating balls that can be customized to a player's strengths and weaknesses, and even allowing for the combination of characteristics that were formerly mutually-exclusive.

Titleist's Pro V1, Taylormade TP5, and Callaway Supersoft exemplify modern advancements in golf ball aerodynamics. The Titleist Pro V1 boasts a tightly wound 388-dimple design, minimizing gaps between dimples for better aerodynamics. On the other hand, the Taylormade TP5 features a combination of circular and hexagonal dimples to reduce drag. Lastly, Callaway balls showcase a sleek, completely hexagonal design for straighter ball flights.

Liquid cores were commonly used in golf balls as early as 1917.[13] The liquid cores in many of the early balls contained a caustic liquid, typically an alkali, causing eye injuries to children who happened to dissect a golf ball out of curiosity.[14] By the 1920s, golf ball manufacturers had stopped using caustic liquids, but into the 1970s and 1980s golf balls were still at times exploding when dissected and were causing injuries due to the presence of crushed crystalline material present in the liquid cores.[15]

In 1967, Spalding purchased a patent for a solid golf ball from Jim Bartsch.[16] His original patent defined a ball devoid of the layers in earlier designs, but Bartsch's patent lacked the chemical properties needed for manufacturing. Spalding's chemical engineering team developed a chemical resin that eliminated the need for the layered components entirely. Since then, the majority of non-professional golfers have transitioned to using solid core (or "2-piece") golf balls.[11][17]

The specifications for the golf ball continue to be governed by the ruling bodies of the game; namely, The R&A, and the United States Golf Association (USGA).

Biodegradable Golf Balls

The early wood, featherie and guttie balls were made from biodegradable materials. However, due to the industrial revolution and the invention of vulcanization, balls increasingly became made from non-biodegradable materials. During the late 2000's a few new biodegradable golf balls came into the market, including some made from wood, lobster shells or cornstarch.[18]

Regulations

The Rules of Golf, jointly governed by the R&A and the USGA, state in Appendix III that the diameter of a "conforming" golf ball cannot be any smaller than 1.680 inches (42.67 mm), and the weight of the ball may not exceed 1.620 ounces (45.93 g). The ball must also have the basic properties of a spherically symmetrical ball, generally meaning that the ball itself must be spherical and must have a symmetrical arrangement of dimples on its surface. While the ball's dimples must be symmetrical, there is no limit to the number of dimples allowed on a golf ball.[19] Additional rules direct players and manufacturers to other technical documents published by the R&A and USGA with additional restrictions, such as radius and depth of dimples, maximum launch speed from test apparatus (generally defining the coefficient of restitution) and maximum total distance when launched from the test equipment.

In general, the governing bodies and their regulations seek to provide a relatively level playing field and maintain the traditional form of the game and its equipment, while not completely halting the use of new technology in equipment design.

Until 1990, it was permissible to use balls of less than 1.68 inches in diameter in tournaments under the jurisdiction of the R&A, which differed in its ball specifications rules from those of the USGA.[20] This ball was commonly called a "British" ball, while the golf ball approved by the USGA was simply the "American ball". The smaller diameter gave the player a distance advantage, especially in high winds, as the smaller ball created a similarly smaller "wake" behind it.

Aerodynamics

When a golf ball is hit, the impact, which lasts less than a millisecond, determines the ball's velocity, launch angle and spin rate, all of which influence its trajectory and its behavior when it hits the ground.

A ball moving through air experiences two major aerodynamic forces: lift, and drag. Dimpled balls fly farther than non-dimpled balls due to the combination of these two effects.[21]

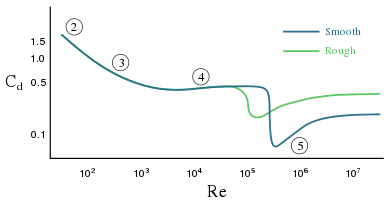

•2: attached flow (Stokes flow) and steady separated flow,

•3: separated unsteady flow, having a laminar flow boundary layer upstream of the separation, and producing a vortex street,

•4: separated unsteady flow with a laminar boundary layer at the upstream side, before flow separation, with downstream of the sphere a chaotic turbulent wake,

•5: post-critical separated flow, with a turbulent boundary layer.

First, the dimples on the surface of a golf ball cause the boundary layer on the upstream side of the ball to transition from laminar to turbulent. The turbulent boundary layer is able to remain attached to the surface of the ball much longer than a laminar boundary with fewer eddies and so creates a narrower low-pressure wake and hence less pressure drag. The reduction in pressure drag causes the ball to travel further.[22]

Second, backspin generates lift by deforming the airflow around the ball,[23] in a similar manner to an airplane wing. This is called the Magnus effect. The dimples on a golf ball deform the air around the ball quickly causing a turbulent airflow that results in more Magnus lift than a smooth ball would experience.[24]

Backspin is imparted in almost every shot due to the golf club's loft (i.e., angle between the clubface and a vertical plane). A backspinning ball experiences an upward lift force which makes it fly higher and longer than a ball without spin.[25]

Curvature of the ball flight occurs when the clubface is not aligned perpendicularly to the club direction at impact, leading to an angled spin axis that causes the ball to curve to one side or the other based on difference between the face angle and swing path at impact. Because the ball's spin during flight is angled, and because of the Magnus effect, the ball will take on a curved path during its flight. Some dimple designs claim to reduce the sidespin effects to provide a straighter ball flight.

Other effects can change the flight behaviour of the ball. Factors such as dynamic lie (the angle of the shaft at impact relative to the ground and its manufactured neutral angle), strike location if the player is using a wood due to the curved face, and external factors such as wind and debris.

To keep the aerodynamics optimal, the golf ball needs to be clean, including all dimples. Thus, it is advisable that golfers wash their balls whenever permissible by the rules of golf. Golfers can wash their balls manually using a wet towel or using a ball washer of some type.

Design

Dimples first became a feature of golf balls when English engineer and manufacturer William Taylor, co-founder of the Taylor-Hobson company, registered a patent for a dimple design in 1905.[26] William Taylor had realized that golf players were trying to make irregularities on their balls, noticing that used balls were going further than new ones. Hence he decided to make systematic tests to determine what surface formation would give the best flight. He then developed a pattern consisting of regularly spaced indentations over the entire surface, and later tools to help produce such balls in series.[27] Other types of patterned covers were in use at about the same time, including one called a "mesh" and another named the "bramble", but the dimple became the dominant design due to "the superiority of the dimpled cover in flight".[28]

Most modern golf balls have about 300–500 dimples,[29] though there have been balls with more than 1000 dimples. The record holder was a ball with 1,070 dimples—414 larger ones (in four different sizes) and 656 pinhead-sized ones.[citation needed]

Officially sanctioned balls are designed to be as symmetrical as possible. This symmetry is the result of a dispute that stemmed from the Polara, a ball sold in the late 1970s that had six rows of normal dimples on its equator but very shallow dimples elsewhere. This asymmetrical design helped the ball self-adjust its spin axis during the flight. The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls. Polara's producer sued the USGA and the association paid US$1.375 million in a 1985 out-of-court settlement.[30]

Golf balls are traditionally white, but are commonly available in other colors, some of which may assist with finding the ball when lost or when playing in low-light or frosty conditions. As well as bearing the maker's name or logo, balls are usually printed with numbers or other symbols to help players identify their ball.

Behavior

Today, golf balls are manufactured using a variety of different materials, offering a range of playing characteristics to suit the player's abilities and desired flight and landing behaviours.

A key consideration is "compression", typically determined by the hardness of the ball's core layers. A harder "high-compression" ball will fly further because of the more efficient transfer of energy into the ball, but will also transmit more of a shock through the club to the player's hands (a "hard feel"). A softer "low-compression" ball will do just the opposite. Golfers typically prefer a softer feel, especially in the "short game", as the softer ball typically also has greater backspin with lofted irons. However, a softer ball reduces drive distance, as it wastes more energy in compression. This makes it more difficult for players to get a birdie or eagle, as it can take more strokes to get on the green.

Another consideration is "spin", affected by compression and by the cover material – a "high-spin" ball allows more of the ball's surface to contact the clubface at impact, allowing the grooves of the clubface to "grip" the ball and induce more backspin at launch. Backspin creates lift that can increase carry distance, and also provides "bite" which allows a ball to arrest its forward motion at the initial point of impact, bouncing straight up or even backwards, allowing for precision placement of the ball on the green with an approach shot. However, high-spin cover materials, typically being softer, are less durable which shortens the useful life of the ball, and backspin is not desirable on most long-distance shots, such as with the driver, as it causes the shot to "balloon" and then to bite on the fairway, when additional rolling distance is usually desired.

Lastly, the pattern of dimples plays a role. By regulation, the arrangement of the dimples on the ball must be as symmetrical as possible. However, the dimples do not all have to be the same size, nor be in a uniform distribution. This allows designers to arrange the dimple patterns in such a way that the resistance to spinning is lower along certain axes of rotation and higher along others. This causes the ball to "settle" into one of these low-resistance axes that (golfers hope) is close to parallel with the ground and perpendicular to the direction of travel, thereby eliminating "sidespin" induced by a slight mishit, which will cause the ball to curve off its intended flight path. A badly mishit ball will still curve, as the ball will settle into a spin axis that is not parallel with the ground which, much like an aircraft's wings, will cause the shot to bank either to the left or to the right.

Selection

There are many types of golf balls on the market, and customers often face a difficult decision. Golf balls are divided into two categories: recreational and advanced balls. Recreational balls are oriented toward the ordinary golfer, who generally have low swing speeds (80 miles per hour (130 km/h) or lower) and lose golf balls on the course easily. These balls are made of two layers, with the cover firmer than the core. Their low compression and side spin reduction characteristics suit the lower swing speeds of average golfers quite well. Furthermore, they generally have lower prices than the advanced balls, lessening the financial impact of losing a ball to a hazard or out of bounds.

Advanced balls are made of multiple layers (three or more), with a soft cover and firm core. They induce a greater amount of spin from lofted shots (wedges especially), as well as a sensation of softness in the hands in short-range shots. However, these balls require a much greater swing speed and thus greater physical strength to properly compress at impact. If the compression of a golf ball does not match a golfer's swing speed, either a lack of compression or over-compression will occur, resulting in loss of distance. Other choices consumers must make include brand and color, with colored balls and better brands generally being more expensive.

Practice/range balls

A practice ball or range ball is similar to a recreational golf ball, but is designed to be inexpensive, durable and have a shorter flight distance, while still retaining the principal behaviors of a "real" golf ball and so providing useful feedback to players. All of these are desirable qualities for use in an environment like a driving range, which may be limited in maximum distance, and must have many thousands of balls on-hand at any time that are each hit and mis-hit hundreds of times during their useful life.

To accomplish these ends, practice balls are typically harder-cored than even recreational balls, have a firmer, more durable cover to withstand the normal abrasion caused by a club's hitting surface, and are made as cheaply as possible while maintaining a durable, quality product. Practice balls are typically labelled with "PRACTICE" in bold lettering, and often also have one or more bars or lines printed on them, which allow players (and high-speed imaging aids) to see the ball's spin more easily as it leaves the tee or hitting turf.

Practice balls conform to all applicable requirements of the Rules of Golf, and as such are legal for use on the course, but as the hitting characteristics are not ideal, players usually opt for a better-quality ball for actual play.

Recycled balls

Players, especially novice and casual players, lose a large number of balls during the play of a round. Balls hit into water hazards, penalty areas, buried deeply in sand, and otherwise lost or abandoned during play are a constant source of litter that groundskeepers must contend with, and can confuse players during a round who may hit an abandoned ball (incurring a penalty by strict rules). An estimated 1.2 billion balls are manufactured every year and an estimated 300 million are lost in the US alone.[31][32]

A variety of devices such as nets, harrows, sand rakes etc. have been developed that aid the groundskeeping staff in efficiently collecting these balls from the course as they accumulate. Once collected, they may be discarded, kept by the groundskeeping staff for their own use, repurposed on the club's driving range, or sold in bulk to a recycling firm. These firms clean and resurface the balls to remove abrasions and stains, grade them according to their resulting quality, and sell the various grades of playable balls back to golfers through retailers at a discount.

Used or recycled balls with obvious surface deformation, abrasion or other degradation are known informally as "shags", and while they remain useful for various forms of practice drills such as chipping, putting and driving, and can be used for casual play, players usually opt for used balls of higher quality, or for new balls, when playing in serious competition. Other grades are typically assigned letters or proprietary terms, and are typically differentiated by the cost and quality of the ball when new and the ability of the firm to restore the ball to "like-new" condition. The "top grade" balls are typically balls that are considered the current state of the art and, after cleaning and surfacing, are indistinguishable externally from a new ball sold by the manufacturer.

Markouts/X-outs

In addition to recycled balls, casual golfers wishing to procure quality balls at a discount price can often purchase "X-outs". These are "factory seconds" – balls which have failed the manufacturer's quality control testing standards and which the manufacturer therefore does not wish to sell under its brand name. To avoid a loss of money on materials and labor, however, the balls which still generally conform to the Rules are marked to obscure the brand name (usually with a series of "X"s, hence the most common term "X-out"), packaged in generic boxes and sold at a deep discount.

Typically, the flaw that caused the ball to fail QC does not have a significant effect on its flight characteristics (balls with serious flaws are usually discarded outright at the manufacturing plant), and so these "X-outs" will often perform identically to their counterparts that have passed the company's QC. They are thus a good choice for casual play. However, because the balls have been effectively "disowned" for practical and legal purposes by their manufacturer, they are not considered to be the same as the brand-name balls on the USGA's published Conforming Golf Ball List. Therefore, when playing in a tournament or other event that requires the ball used by the player to appear on this list as a "condition of competition", X-outs of any kind are illegal.

Marking and personalization

Golfers need to distinguish their ball from other players' to ensure that they do not play the wrong ball. This is often done by making a mark on the ball using a permanent marker pen such as a Sharpie. A wide number of markings are used; a majority of players either simply write their initial in a particular color, or color in a particular arrangement of the dimples on the ball. Many players make multiple markings so that at least one can be seen without having to lift the ball. Marking tools such as stamps and stencils are available to speed the marking process.

Alternatively, balls are usually sold pre-marked with the brand and model of golf ball, and also with a letter, number or symbol. This combination can usually (but not always) be used to distinguish a player's ball from other balls in play and from lost or abandoned balls on the course. Companies, country clubs and event organizers commonly have balls printed with their logo as a promotional tool, and some professional players are supplied with balls by their sponsors which have been custom-printed with something unique to that player (their name, signature, or a personal symbol).

Radio location

Golf balls with embedded radio transmitters to allow lost balls to be located were first introduced in 1973, only to be rapidly banned for use in competition.[33][34] More recently RFID transponders have been used for this purpose, though these are also illegal in tournaments. This technology can however be found in some computerized driving ranges. In this format, each ball used at the range has an RFID with its own unique transponder code. When dispensed, the range registers each dispensed ball to the player, who then hits them towards targets in the range. When the player hits a ball into a target, they receive distance and accuracy information calculated by the computer. The use of this technology was first commercialized by World Golf Systems Group to create TopGolf, a brand and chain of computerized ranges now owned by Callaway Golf.

World records

Canadian long drive champion Jason Zuback broke the world ball speed record on an episode of Sport Science with a golf ball speed of 328 km/h (204 mph). The previous record of 302 km/h (188 mph) was held by José Ramón Areitio, a Jai Alai player.[35]

References

- ^ "Golf Ball History from Hairy to Haskell 2014". scottishgolfhistory.org. Archived from the original on 2014-10-29.

- ^ Seltzer, Leon (2008). Golf: The Science and the Art. Tate Publishing & Enterprises. p. 37. ISBN 978-1602478480.

- ^ Cook, Kevin (May 2007). "Feature Interview with Kevin Cook". golfclubatlas.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007.

- ^ "Timeline of the history of golf". St Andrews Links Trust. Archived from the original on 2009-06-02.

- ^ "Golf ball inventor dead" (PDF). The New York Times. April 26, 1904. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-18. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "gutta percha golf balls". The Antiques Bible. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "Golf". World-Wide Encyclopedia. 1896.

- ^ Krens, Art (March 6, 1932). "Golf ball industry unharmed by Depression". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). National Editorial Association. p. 10. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Bibliographic data". Espacenet.com. Archived from the original on 2023-07-18. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- ^ Brenner, Morgan G. (2009-09-12). The Majors of Golf: Complete Results of the Open, the U.S. Open, the PGA Championship and the Masters, 1860–2008. McFarland. ISBN 9780786453955. Archived from the original on 2023-07-18. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ a b "Hot, new solid-core balls have nearly KO'd their wound-ball rivals". Golf Digest. June 2001. Archived from the original on 2012-05-31 – via findarticles.com.

- ^ "DuPont™ Surlyn® golf ball applications". dupont.com. 2005-12-02. Archived from the original on 2013-07-31. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ^ Rowland, W.D. (October 1917). "Golf Ball Rupture In Mouth With Acid Burns To Larynx Trachea Bronchi Oesophagus Stomach And Death In Thirty Hours From Bronchopneumonia". The Journal of Ophthalmology, Otology and Laryngology. 23 (10): 678–688. Archived from the original on 2023-07-18. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Crigler, L.W. (1913). "Burn of Eyeball Due to Caustic Contents of Golf-Ball". Journal of the American Medical Association. 60 (17): 1297. doi:10.1001/jama.1913.04340170025018. Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Lucas, D.R.; et al. (1976). "Ocular injuries from liquid golf ball cores". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 60 (11): 740–747. doi:10.1136/bjo.60.11.740. PMC 1042829. PMID 1009050.

- ^ "Obituaries: James R. Bartsch, Inventor, 58". The New York Times. March 7, 1991. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ "Golf Ball Knowledge: Pieces". golfball-guide.de. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 26 Sep 2015.

- ^ Reporter, Chris Zelkovich Sports (2011-04-14). "Fore! New biodegradable golf balls are made from lobster shells". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "How Many Dimples Are on a Golf Ball? Why do Balls Have Dimples?". Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ "Golf Timeline – 1990 – The Year in Golf, 1990". Golf.about.com. Archived from the original on 2013-04-16. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ "Golf Ball Dimples: Understanding the Science Behind How They Improve Golf Ball Performance".

- ^ "Golf Ball Dimples & Drag". Aerospaceweb.org. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ^ Nakagawa, Masamichi; Yabe, Takashi; Misaki, Masaya; Manome, Kazuto; Yamada, Tetsuri (2005). "202 Aerodynamic Coefficients of a Dimpled Sphere in Back-Spin". The Proceedings of the JSME Annual Meeting. 2005 (2): 89–90. doi:10.1299/jsmemecjo.2005.2.0_89.

- ^ "Why Do Golf Balls Have Dimples?" Archived 2020-08-10 at the Wayback Machine, Ivy Golf

- ^ DeForest, Craig. Physics/General/golf Archived 2018-10-24 at the Wayback Machine. math.ucr.edu

- ^ US patent 878254, William Taylor, "Golf-ball", issued 1908-02-04

- ^ "The Taylor Hobson Story". Taylor hobson. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ^ Feldman, David (1989). When Do Fish Sleep? And Other Imponderables of Everyday Life. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 46. ISBN 0-06-016161-2.

- ^ "How do dimples in golf balls affect their flight?". Scientific American. September 19, 2005. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Scouting; Duffer's Dream Finally Over". The New York Times. 1986-01-08. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ^ Scott, Alex (12 June 2017). "What's inside golf balls, and can chemistry make them fly farther?". Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Pennington, Bill (2 May 2010). "The Burden and Boon of Lost Golf Balls". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ History of the rules of golf Archived 2008-07-16 at the Wayback Machine. Ruleshistory.com. Retrieved on 2013-11-03.

- ^ Euronics Limited. US Patent 3782730 Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine. Publication Date: 1 January 1974 .

- ^ "FSN Sport Science – Episode 7 – Myths – Jason Zuback". Sport Science. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

Further reading

- Penner, A.R. (2001). "The physics of golf: The convex face of a driver". American Journal of Physics. 69 (10): 1073–1081. Bibcode:2001AmJPh..69.1073P. doi:10.1119/1.1380380. hdl:10613/2816.

- Penner, A.R. (2001). "The physics of golf: The optimum loft of a driver". American Journal of Physics. 69 (5): 563–568. Bibcode:2001AmJPh..69..563P. doi:10.1119/1.1344164. hdl:10613/2821.

External links

- Online golf ball museum with more than 1000 different golf balls

- Golf Balls Get Built-In Zip, July 1950, Popular Science detailed article on production of Golf Balls