Golden Temple

| Golden Temple | |

|---|---|

Harmandir Sahib Darbar Sahib | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sikhism |

| Location | |

| Location | Amritsar |

| State | Punjab |

| Country | India |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°37′12″N 74°52′35″E / 31.62000°N 74.87639°E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Guru Arjan |

| Groundbreaking | December 1581[1] |

| Completed | 1589 (temple), 1604 (with Adi Granth) [1] |

| Website | |

| sgpc | |

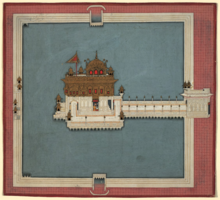

The Golden Temple (also known as the Harmandir Sāhib (lit. 'House of God', Punjabi pronunciation: [ɦəɾᵊmən̪d̪əɾᵊ saːɦ(ɪ)bᵊ]), or the Darbār Sāhib, (lit. ''exalted court'', [d̪əɾᵊbaːɾᵊ saːɦ(ɪ)bᵊ] or Suvaran Mandir[2]) is a gurdwara located in the city of Amritsar, Punjab, India.[3][4] It is the pre-eminent spiritual site of Sikhism. It is one of the holiest sites in Sikhism, alongside the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur in Kartarpur, and Gurdwara Janam Asthan in Nankana Sahib.[3][5]

The man-made pool (sarovar) on the site of the temple (gurdwara) was completed by the fourth Sikh Guru, Guru Ram Das, in 1577.[6][7] In 1604, Guru Arjan, the fifth Sikh Guru, placed a copy of the Adi Granth in the Golden Temple and was a prominent figure in its development.[3][8] The gurdwara was repeatedly rebuilt by the Sikhs after it became a target of persecution and was destroyed several times by the Mughal and invading Afghan armies.[3][5][9] Maharaja Ranjit Singh, after founding the Sikh Empire, rebuilt it in marble and copper in 1809, and overlaid the sanctum with gold leaf in 1830. This has led to the name the Golden Temple.[10][11][12]

The Golden Temple is spiritually the most significant shrine in Sikhism. It became a centre of the Singh Sabha Movement between 1883 and the 1920s, and the Punjabi Suba movement between 1947 and 1966. In the early 1980s, the gurdwara became a centre of conflict between the Indian government and a radical movement led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.[13] In 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sent in the Indian Army as part of Operation Blue Star, leading to the deaths of thousands of soldiers, militants and civilians, as well as causing significant damage to the gurdwara and the destruction of the nearby Akal Takht. The gurdwara complex was rebuilt again after the 1984 attack on it.[5]

The Golden Temple is an open house of worship for all people, from all walks of life and faiths.[3] It has a square plan with four entrances, and a circumambulation path around the pool. The four entrances to the gurudwara symbolises the Sikh belief in equality and the Sikh view that all people are welcome into their holy place.[14] The complex is a collection of buildings around the sanctum and the pool.[3] One of these is Akal Takht, the chief centre of religious authority of Sikhism.[5] Additional buildings include a clock tower, the offices of the Gurdwara Committee, a Museum and a langar – a free Sikh community-run kitchen that offers a vegetarian meal to all visitors without discrimination.[5] Over 150,000 people visit the holy shrine everyday for worship.[15] The gurdwara complex has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its application is pending on the tentative list of UNESCO.[16]

Nomenclature

The Harmandir Sahib (Gurmukhi: ਹਰਿਮੰਦਰ ਸਾਹਿਬ) is also spelled as Harimandar or Harimandir Sahib.[3][17] It is also called the Durbār Sahib (ਦਰਬਾਰ ਸਾਹਿਬ), which means "sacred audience", as well as the Golden Temple for its gold leaf-covered sanctum centre.[5] The word "Harmandir" is composed of two words: "Hari", which scholars translate as "God ",[3] and "mandir", which means "house".[18] "Sahib" is further appended to the shrine's name, the term often used within Sikh tradition to denote respect for places of religious significance.[19] The Sikh tradition has several Gurdwaras named "Harmandir Sahib", such as those in Kiratpur and Patna. Of these, the one in Amritsar is most revered.[20][21]

History

According to the Sikh historical records, the land that became Amritsar and houses the Harimandir Sahib was chosen by Guru Amar Das, the third Guru of the Sikh tradition. It was then called Guru Da Chakk, after he had asked his disciple Ram Das to find land to start a new town with a man-made pool as its central point.[6][7][22] After Guru Ram Das succeeded Guru Amar Das in 1574, and in the face of hostile opposition from the sons of Guru Amar Das,[23] Guru Ram Das founded the town that came to be known as "Ramdaspur". He started by completing the pool with the help of Baba Buddha (not to be confused with the Buddha of Buddhism). Guru Ram Das built his new official centre and home next to it. He invited merchants and artisans from other parts of India to settle in the new town with him.[22]

Ramdaspur town expanded during the time of Guru Arjan financed by donations and constructed by voluntary work. The town grew to become the city of Amritsar, and the area grew into the temple complex).[24] The construction activity between 1574 and 1604 is described in Mahima Prakash Vartak, a semi-historical Sikh hagiography text likely composed in 1741, and the earliest known document dealing with the lives of all the ten Gurus.[25] Guru Arjan installed the scripture of Sikhism inside the new gurdwara in 1604.[24] Continuing the efforts of Guru Ram Das, Guru Arjan established Amritsar as a primary Sikh pilgrimage destination. He wrote a voluminous amount of Sikh scripture including the popular Sukhmani Sahib.[26][27]

Construction

Guru Ram Das acquired the land for the site. Two versions of stories exist on how he acquired this land. In one, based on a Gazetteer record, the land was purchased with Sikh donations of 700 rupees from the people and owners of the village of Tung. In another version, Emperor Akbar is stated to have donated the land to the wife of Guru Ram Das.[22][28]

In 1581, Guru Arjan initiated the construction of the Gurdwara.[1] During the construction the pool was kept empty and dry. It took 8 years to complete the first version of the Harmandir Sahib. Guru Arjan planned a gurdwara at a level lower than the city to emphasise humility and the need to efface one's ego before entering the premises to meet the Guru.[1] He also demanded that the gurdwara compound be open on all sides to emphasise that it was open to all. The sanctum inside the pool where his Guru seat was, had only one bridge to emphasise that the end goal was one, states Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair.[1] In 1589, the gurdwara made with bricks was complete. Guru Arjan is believed by some later sources to have invited the Sufi saint Mian Mir of Lahore to lay its foundation stone, signalling pluralism and that the Sikh tradition welcomed all.[1] This belief is however unsubstantiated.[29][30] According to Sikh traditional sources such as Sri Gur Suraj Parkash Granth it was laid by Guru Arjan himself.[31] After the inauguration, the pool was filled with water. On 16 August 1604, Guru Arjan completed expanding and compiling the first version of the Sikh scripture and placed a copy of the Adi Granth in the gurdwara. He appointed Baba Buddha as the first Granthi.[32]

Ath Sath Tirath, which means "shrine of 68 pilgrimages", is a raised canopy on the parkarma (circumambulation marble path around the pool).[3][8][33] The name, as stated by W. Owen Cole and other scholars, reflects the belief that visiting this temple is equivalent to 68 Hindu pilgrimage sites in the Indian subcontinent, or that a Tirath to the Golden Temple has the efficacy of all 68 Tiraths combined.[34][35] The completion of the first version of the Golden Temple was a major milestone for Sikhism, states Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, because it provided a central pilgrimage place and a rallying point for the Sikh community, set within a hub of trade and activity.[1]

Mughal Empire era destruction and rebuilding

The growing influence and success of Guru Arjan drew the attention of the Mughal Empire. Guru Arjan was arrested under the orders of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir and asked to convert to Islam.[36][37] He refused, was tortured and executed in 1606.[36][37][38] Guru Arjan's son and successor Guru Hargobind fought a Battle at Amritsar and later left Amritsar and its surrounding areas in 1635 for Kiratpur.[39][40] For about a century after the Golden Temple was occupied by the Minas.[39] In the 18th century, Guru Gobind Singh after creating the Khalsa sent Bhai Mani Singh to take back the temple.[39][41][42] The Golden Temple was viewed by the Mughal rulers and Afghan Sultans as the centre of Sikh faith and it remained the main target of persecution.[9] After the original temple was destroyed by hostile forces, the shrine was reconstructed in 1764 (a date which H.H. Cole affirms in his monograph on the temple), however most of the elaborate decorations and additions were added to the shrine in the early 19th century.[43] However, according to Giani Gian Singh's Tawarikh Sri Amritsar (1889), a slightly later date of 1776 is given for the construction of the temple tank (sarovar), the temple edifice proper, the causeway, and the entry gateway or archway (Darshani Deori).[43]

The Golden Temple was the centre of historic events in Sikh history:[44][10]

- In 1709, the governor of Lahore sent in his army to suppress and prevent the Sikhs from gathering for their festivals of Vaisakhi and Diwali. But the Sikhs defied by gathering in the Golden Temple. In 1716, Banda Singh and numerous Sikhs were arrested and executed.

- In 1737, the Mughal governor ordered the capture of the custodian of the Golden Temple named Mani Singh and executed him. He appointed Masse Khan as the police commissioner who then occupied the Temple and converted it into his entertainment centre with dancing girls. He befouled the pool. Sikhs avenged the sacrilege of the Golden Temple by assassinating Masse Khan inside the Temple in August 1740.

- In 1746, another Lahore official Diwan Lakhpat Rai working for Yahiya Khan, and seeking revenge for the death of his brother, filled the pool with sand. In 1749, Sikhs restored the pool when Muin ul-Mulk slackened Mughal operations against Sikhs and sought their help during his operations in Multan.

- In 1757, the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Durrani, also known as Ahmad Shah Abdali, attacked Amritsar and desecrated the Golden Temple.[45] He had waste poured into the pool along with entrails of slaughtered cows, before departing for Afghanistan. The Sikhs restored it again.

- In 1762, Ahmad Shah Durrani returned and had the Golden Temple blown up with gunpowder.[45] Sikhs returned and celebrated Diwali in its premises. In 1764, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia collected donations to rebuild the Golden Temple.[43] A new main gateway (Darshan Deorhi), causeway and sanctum were completed in 1776, while the floor around the pool was completed in 1784.[43] The Sikhs also completed a canal to bring in fresh water from Ravi River for the pool.

- Shri Harmandir Sahib was attacked by the Afghan forces under Ahmed Shah Durrani on 1 December 1764. Baba Gurbaksh Singh along with 29 other Sikhs lead a last stand against the much larger Afghan forces and were killed in the skirmish.[46] Abdali then destroyed Shri Harmandir Sahib for the 3rd time.[47][45]

Ranjit Singh era reconstruction

Ranjit Singh founded the nucleus of the Sikh Empire at the age of 36 with help of Sukerchakia Misl forces he inherited and those of his mother-in-law Rani Sada Kaur. In 1802, at age 22, he took Amritsar from the Bhangi Sikh misl, paid homage at the Golden Temple and announced that he would renovate and rebuild it with marble and gold.[48][43] The Sikh ruler donated the gilded copper panels for the roof, which was worth 500,000 rupees in the erstwhile currency.[43] He entrusted Mistri Yar Muhammad Khan to carry-out the roofing work, who himself was supervised by Bhai Sand Singh.[43] The first gilded copper panel was placed on the shrine in 1803.[43]

Various personalities helped decorate and embellish the ceiling of the first floor, with names of some contributors to the cause being Tara Singh Gheba, Partap Singh, Jodh Singh, and Ganda Singh Peshawari.[43] Ganda Singh Peshawari sent his donation in the year 1823.[43] For the decoration and gilding with copper of the main entryway and archway to the causeway leading to the temple proper, known as the Darshani Deori, the prime personality who helped assist with this work was Raja Sangat Singh of Jind State.[43] Due to the central and paramount importance of the shrine in Sikhism, essentially every Sikh sardar of the era had contributed or donated in some manner to assist with the architectural and artistic renovations of the shrine.[43] Owing to the large number of people helping with the renovation work back then, it is difficult to account for when certain parts of the temple were constructed or decorated and by whom (aside from instances where the work has a date inscribed to it) and a chronological record of how the temple evolved over time (in-regards to its murals, decorations, and other aspects) is near-impossible to complete.[43]

The Temple was renovated in marble and copper in 1809, and in 1830 Ranjit Singh donated gold to overlay the sanctum with gold leaf.[10] There is an inscription on embossed metal located at the entrance to the temple proper which commemorates the renovations of the temple undertaken by Ranjit Singh and done through Giani Sant Singh, of the Giani Samparda.[43]

"The Great Guru in His wisdom looked upon Maharaja Ranjit Singh as his chief servitor and Sikh and, in his benevolence, bestowed on him the privilege of serving the temple."

— English translation of a Gurmukhi inscription on embossed metal located at the entrance way to the temple, translated in 'Punjab Art and Culture' (1988), page 59, by Kanwarjit Singh Kang

After learning of the Gurdwara through Maharaja Ranjit Singh,[49] the 7th Nizam of Hyderabad "Mir Osman Ali Khan" started giving yearly grants towards it.[50] The management and operation of Durbar Sahib – a term that refers to the entire Golden Temple complex of buildings, was taken over by Ranjit Singh. He appointed Sardar Desa Singh Majithia (1768–1832) to manage it and made land grants whose collected revenue was assigned to pay for the Temple's maintenance and operation.

Ranjit Singh also made the position of Temple officials hereditary.[3] The Giani family was the only family allowed to do Katha in the Golden Temple, they served the Sikh community till 1921, when the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee came into power, they were the only family allowed to do Katha since 1788 and were also he heads of the Giani Samparda, they had built all the Bungas around the Golden Temple and helped in construction work including overlaying the temple with Gold and Marble.[51] One of the main Bungas that was destroyed in 1988 was the Burj Gianian. The other family were the Kapurs, who were made as the Head Granthis, this included the ancestors of Bhai Jawahir Singh Kapur who also did try to become the Head Granthi in the late 1800s, but was not allowed (his father Bhai Atma Singh, grandfather Bhai Mohar Singh and their ancestors were also Head Granthis).[52]

Destruction and reconstruction after Indian independence

The destruction of the temple complex occurred during the Operation Blue Star. It was the codename of an Indian military action carried out between 1 and 8 June 1984 to remove militant Sikh Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) complex in Amritsar, Punjab. The decision to launch the attack rested with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.[53] In July 1982, Harchand Singh Longowal, the President of the Sikh political party Akali Dal, had invited Bhindranwale to take up residence in the Golden Temple Complex to evade arrest.[54][55] The government claimed Bhindranwale later made the sacred temple complex an armoury and headquarters.[56]

On 1 June 1984, after negotiations with the militants failed, Indira Gandhi ordered the army to launch Operation Blue Star, simultaneously attacking scores of Sikh temples across Punjab.[57] A variety of army units and paramilitary forces surrounded the Golden Temple complex on 3 June 1984. The fighting started on 5 June with skirmishes and the battle went on for three days, ending on 8 June. A clean-up operation codenamed Operation Woodrose was also initiated throughout Punjab.[58]

The army had underestimated the firepower possessed by the militants, whose armament included Chinese-made rocket-propelled grenade launchers with armour piercing capabilities. Tanks and heavy artillery were used to attack the militants, who responded with anti-tank and machine-gun fire from the heavily fortified Akal Takht. After a 24-hour firefight, the army gained control of the temple complex. Casualty figures for the army were 83 dead and 249 injured.[59] According to the official estimates, 1,592 militants were apprehended and there were 493 combined militant and civilian casualties.[60] According to the government claims, high civilian casualties were attributed to militants using pilgrims trapped inside the temple as human shields.[61]

Brahma Chellaney, the Associated Press's South Asia correspondent, was the only foreign reporter who managed to stay on in Amritsar despite the media blackout.[62] His dispatches, filed by telex, provided the first non-governmental news reports on the bloody operation in Amritsar. His first dispatch, front-paged by The New York Times, The Times of London and The Guardian, reported a death toll about twice of what authorities had admitted. According to the dispatch, about 780 militants and civilians and 400 troops had perished in fierce gun-battles.[63] Chellaney reported that about "eight to ten" men suspected Sikh militants had been shot with their hands tied. In that dispatch, Chellaney interviewed a doctor who said he had been picked up by the army and forced to conduct postmortems despite the fact he had never done any postmortem examination before.[64] In reaction to the dispatch, the Indian government charged Chellaney with violating Punjab press censorship, two counts of fanning sectarian hatred and trouble, and later with sedition,[65] calling his report baseless and disputing his casualty figures.[66]

The military action in the temple complex was criticised by Sikhs worldwide, who interpreted it as an assault on the Sikh religion.[67] Many Sikh soldiers in the army deserted their units;[68] several Sikhs resigned from civil administrative office and returned awards received from the Indian government. Five months after the operation, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated in an act of revenge by her two Sikh bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh.[55] Public outcry over Gandhi's death led to the killings of more than 3,000 Sikhs in Delhi alone, in the ensuing 1984 anti-Sikh riots.[69] A few months after the government operation of 1984, major kar seva renovations were undertaken at the shrine complex, including a complete draining and then cleaning of the temple tank (sarovar) by volunteers.[43]

Following the operation the central government demolished hundreds of houses and created a corridor around the compound called "Galliara" (also spelled Galiara or Galyara) for security reasons.[70] This was made into a public park and opened in June 1988.[71][72][73][74]

In December 2021, a young man was allegedly beaten to death after disrupting the Rehras Sahib (evening prayer) at the sanctum of the temple. He reportedly jumped over a railing and picked up the sword lying before the temple's copy of the Guru Granth Sahib, before attempting to touch the Guru Granth Sahib itself. He was subsequently overpowered by the sangat and received fatal injuries to the head.[75]

Damage from 2023 events

- 2023 Golden Temple blasts on 7 May and on 9 May 2023.[76]

Description

Architecture

The Golden Temple's architecture reflects different architectural practices prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, as various iterations of temple were rebuilt and restored.[43]

The first structure of the Harmandir Sahib constructed under the purview of Guru Arjan combined the concepts of dharamsaals and the holy water tanks (sarovar).[43] Rather than copying the traditional method of Hindu temple construction by building the shrine on a high plinth, Guru Arjan rather decided to build the shrine lower than the surroundings so that devotees would have to walk downwards to reach it.[43] The four entrances represented that the Sikh faith was equally open to all four of the traditional Indian caste classifications (varnas).[43] No surviving account, depiction, or record is extant or known of the proto-type, pre-1764 Harmandir Sahib that was built by the Sikh gurus themselves.[43] However, Kanwarjit Singh Kang believes the original, Guru-constructed structure was mostly comparable and similar to the present-day structure said to have been constructed in 1764.[43]

James Fergusson considered the Golden Temple as a specimen of one of the forms that the architecture of Hindu temples developed into in the 19th century.[43] When a list of structures of interest was prepared and published by the colonial government of Punjab in 1875, it was claimed that the architectural design of the Golden Temple, in the form it was constructed as by Ranjit Singh, was based ultimately on the shrine of the Sufi saint Mian Mir.[43] Louis Rousselet stated in 1882 that the shrine was a "handsome style of Jat architecture."[43] Major Henry Hardy Cole described the architecture of the edifice as being primarily drawn from Islamic sources with a significant input from Hindu styles.[43] Percy Brown also classified the temple as being a synthesis of Islamic and Hindu architectural styles, but also observed that the structure has its own unique characteristics and inventions.[43] Hermann Goetz believed that the temple's architecture was a "Kangra transformation of Oudh architecture" that the Sikhs adopted for their own constructions, which he praises, however he also critiqued the temple for having "gaudy" elements commonly found in Indian gurdwaras, an example being the rococo-styled art.[43] The Temple is described by Ian Kerr, and other scholars, as a mixture of the Indo-Islamic Mughal and the Hindu Rajput architecture.[3][77]

The sanctum is a 12.25 x 12.25 metre square with two storeys and a gold leaf dome. This sanctum has a marble platform that is a 19.7 x 19.7 metre square. It sits inside an almost square (154.5 x 148.5 m2) pool called amritsar or amritsarovar (amrit means nectar, sar is short form of sarovar and means pool). The pool is 5.1 metres deep and is surrounded by a 3.7 metre wide circumambulatory marble passage that is circled clockwise. The sanctum is connected to the platform by a causeway and the gateway into the causeway is called the Darshani Ḍeorhi (from Darshana Dvara). For those who wish to take a dip in the pool, the Temple provides a half hexagonal shelter and holy steps to Har ki Pauri.[3][78] Bathing in the pool is believed by many Sikhs to have restorative powers, purifying one's karma.[79] Some carry bottles of the pool water home particularly for sick friends and relatives.[80] The pool is maintained by volunteers who perform kar seva (community service) by draining and desilting it periodically.[79]

There is a section of the shrine known as the Har-Ki-Pauri, located on the backside of the temple proper, where pilgrims and worshippers can take a sip of the water from the holy temple tank.[43] The water used for the daily ritual cleaning of the temple premises is also sourced from this section.[43] The water is mixed with milk to dilute the milk content, with the combined solution used to clean the temple's surfaces on a daily basis.[43]

The sanctum has two floors. The Sikh Scripture Guru Granth Sahib is seated on the lower square floor for about 20 hours every day, and for 4 hours it is taken to its bedroom inside Akal Takht with elaborate ceremonies in a palki, for sukhasana and Prakash.[34] The floor with the seated scripture is raised a few steps above the entrance causeway level. The upper floor in the sanctum is a gallery and connected by stairs. The ground floor is lined with white marble, as is the path surrounding the sanctum. The sanctum's exterior has gilded copper plates. The doors are gold leaf-covered copper sheets with nature motifs such as birds and flowers. The ceiling of the upper floor is gilded, embossed and decorated with jewels. The sanctum dome is semi-spherical with a pinnacle ornament. The sides are embellished with arched copings and small solid domes, the corners adorning cupolas, all of which are covered with gold leaf-covered gilded copper.[3] There is a pavilion located on the second-floor called the Shish Mahal (mirror room).[43]

The floral designs on the marble panels of the walls around the sanctum are Arabesque. The arches include verses from the Sikh scripture in gold letters. The frescoes follow the Indian tradition and include animal, bird and nature motifs rather than being purely geometrical. The stair walls have murals of Sikh Gurus such as the falcon carrying Guru Gobind Singh riding a horse.[3][81]

The Darshani Deorhi is a two-storey structure that houses the temple management offices and treasury. At the exit of the path leading away from the sanctum is the Prasada facility, where volunteers serve a flour-based sweet offering called Karah prasad. Typically, the pilgrims to the Golden Temple enter and make a clockwise circumambulation around the pool before entering the sanctum. There are four entrances to the gurdwara complex signifying the openness to all sides, but a single entrance to the sanctum of the temple through a causeway.[3][82][page needed]

Art

The art of the Golden Temple has rarely been analysed or studied in a serious manner.[43] Within the Shish Mahal on the second-story of the building, there are mirror-work art designs which consist of small pieces of mirror which are inlaid into the walls and ceilings, highlighed with decorations of floral designs.[43] The celings, walls and arches of the structure are embellished by intricate mural artwork.[43] The pietra dura (inlaid stone design) artwork of the shrine, which features avian and other animalistic designs using semi-precious stones, was mostly inspired by the Mughal tradition.[43] The temple premises is also decorated with embossed copper, gach, tukri, jaratkari, and ivory inlay artwork.[43] The external portions of the upper story's walls of the temple have been affixed with beaten copper plates that feature raised designs depicting usually florals and abstracts but there are some depictions of human figures as well.[43] An example of embossed metal designs depicting humans are two raised copper panels located on the front-side of the temple prior, the first which depicts Guru Nanak surrounded by his companions, Bhai Mardana and Bhai Bala, on each side.[43] The second embossed panel features an equestrian portrayal of Guru Gobind Singh.[43]

Gach can be described as a kind of stone or gypsum.[43] Gach was transformed into a paste and used on the walls, similar in nature to lime-plaster.[43] Once applied to the wall, it was decorated into shape with steel cutters and other tools.[43] Sometimes the gach had coloured glass pieces placed on it, which is known as tukri.[43] The Shish Mahal features a lot of examples of tukri work.[43] On the other hand, jaratkari was an art form and method which involved placing inlaid and cut stones of varying colours and types into marble.[43] Surviving exemplars of jaratkari art from the temple can be found on the bottom-section of the exterior walls which are encased with marble panels featuring jaratkari artwork.[43] The jaratkari marble panels in this lower exterior section is classified as pietra dura and semi-precious stones, like lapis lazuli and onyx, were utilised.[43] While the Mughals also decorated their edifices using jaratkari and pietra dura art, what sets apart the Sikh form of the art technique from the Mughal one is that the Sikh jaratkari art form also depicts human and animal figuratives with it, something that is not found in Mughal jaratkari art.[43]

Inlaid ivory work can be witnessed on the doors of the Darshani Deori structure of the complex.[43] The structure of the Darshani Deori was made out of shisham wood, the front of the edifice is overlaid with silverwork, including ornamated silver panels.[43] The back of the structure is decorated with panels consisting of floral and geometric designs but also animal figuratives, such as deer, tigers, lions, and birds.[43] Portions of the inlaid ivory had been coloured red or green, an aspect of the artwork that was praised by H.H. Cole for its harmoniousness.[43]

The oldest extant murals in the complex date back to the 1830s.[45] Most of the vast array of murals that once coated the walls of the complex were destroyed in subsequent renovation works conducted under the guise of kar seva, such as by being covered by marble slabs affixed to the walls.[45] A prominent artist who painted many of the murals in the complex was Gian Singh Naqqash.[45] The mural artwork of the temple consists primarily of floral designs with scattered examples of animal designs and themes.[43] There are over 300 different design patterns dispersed all over the walls of the edifice.[43] These wall paintings were created by Naqqashi artists, who had developed their own lingo to differentiate their various themes and designs.[43] The most prominent design category was referred to as Dehin, which is described as "a medium of expression of the imaginative study of the artist's own creation of idealized forms".[43] The base of dehin is known as Gharwanjh.[43] Gharwanjh is a "decorative device involving knotted grapples between animals".[43] The gharwanjh designs of the Golden Temple features cobras, lions, and elephants holding one another or carrying floral vases which feature fruit and fairies as decoration.[43] The decorative border of the dehin is known as Patta, usually utilising creepers for its design.[43] Furthermore, some dehin feature designs incorporating aquatic creatures.[43]

The only mural depicting human figures within the temple proper is located on the wall behind the northern narrow staircase leading to the top of the shrine, and it is a depiction of Guru Gobind Singh on horseback alongside his retinue leaving the fort of Anandpur, ultimately a mural adaptation of what was originally a Kangra miniature painting.[43] When H.H. Cole wrote about the murals of the Golden Temple, he witnessed many murals depicting Indic mythological scenes but these murals have since been seemingly lost to time and are no longer extant.[43]

While W. Wakefield had recorded that he observed murals depicting erotic scenes painted on the Golden Temple's walls in a work published in 1875, Kanwarjit Singh Kang finds this to be a spurious account which is likely false because there is no corroborative accounts to support this.[43]

The various artists and craftsmen who worked on creating the mural artwork and other accessory art of the temple are mostly unknown and it is nearly impossible to link any particular art piece with a specific name, aside from a very few.[43] A traditional Sikh artist who had worked at the Golden Temple, named Hari Singh, had prepared a list of all the names of the artists, painters (naqqashis), and craftsmen he could recount that had also worked at some point in time at the Golden Temple, the names are as follows: Kishan Singh, Bishan Singh, Kapur Singh, Kehar Singh, Mahant Ishar Singh, Sardul Singh, Jawahar Singh, Mehtab Singh, Mistri Jaimal Singh, Harnam Singh, Ishar Singh (not to be confused with Mahant Ishar Singh), Gian Singh, Lal Singh Tarn Taran, Mangal Singh, Mistri Narain Singh, Mistri Jit Singh, Atma Singh, Darja Mal, and Vir Singh.[43]

Most of the artwork lost over the years, throughout the various changes and renovations to the temple, were murals.[43] Murals started being lost in the temple around the last years of the 19th century, when devotees were allowed to start donating inlaid marble panels to affix to the walls of the shrine.[43] The walls that were covered by these marble panels usually were painted with murals and thus the murals were either hidden under the marble panels or destroyed.[43] The Golden Temple used to have many traditional buildings, known as bungas, surrounding it.[43] These bungas were a great source and collection of murals and thus their artwork was lost when the vast majority of the bungas were demolished over the years under the guise of modernising the religious site and expanding its parikrama.[43] When the Darshani Deori was covered with marble panels, many wall paintings that had been executed by Mahant Ishar Singh were covered up and lost due to them.[43]

Akal Takht and Teja Singh Samundri Hall

In front of the sanctum and the causeway is the Akal Takht building. It is the chief Takht, a centre of authority in Sikhism. Its name Akal Takht means "throne of the Timeless (God)". The institution was established by Guru Hargobind after the martyrdom of his father Guru Arjan, as a place to conduct ceremonial, spiritual and secular affairs, issuing binding writs on Sikh Gurdwaras far from his own location. A building was later constructed over the Takht founded by Guru Hargobind, and this came to be known as Akal Bunga. The Akal Takht is also known as Takht Sri Akal Bunga. The Sikh tradition has five Takhts, all of which are major pilgrimage sites in Sikhism. These are in Anandpur, Patna, Nanded, Talwandi Sabo and Amritsar. The Akal Takht in the Golden Temple complex is the primary seat and chief.[83][84] It is also the headquarters of the main political party of the Indian state of Punjab, Shiromani Akali Dal (Supreme Akali Party).[5] The Akal Takht issues edicts or writs (hukam) on matters related to Sikhism and the solidarity of the Sikh community.

The Teja Singh Samundri Hall is the office of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (Supreme Committee of Temple Management). It is located in a building near the Langar-kitchen and Assembly Hall. This office coordinates and oversees the operations of major Sikh temples.[5][85]

Ramgarhia Bunga and Clock Tower

The Ramgarhia Bunga – the two high towers visible from the parikrama (circumambulation) walkway around the tank,[87] is named after a Sikh subgroup. The red sandstone minaret-style Bunga (buêgā) towers were built in the 18th century, a period of Afghan attacks and temple demolitions. It is named after the Sikh warrior and Ramgarhia misl chief Jassa Singh Ramgarhia. It was constructed as the temple watchtowers for sentinels to watch for any military raid approaching the temple and the surrounding area, help rapidly gather a defence to protect the Golden Temple complex. According to Fenech and McLeod, during the 18th century, Sikh misl chiefs and rich communities built over 70 such Bungas of different shapes and forms around the temple to watch the area, house soldiers and defend the temple.[88] These served defensive purposes, provided accommodation for Sikh pilgrims and served as centres of learning in the 19th century.[88] Most of the Bungas were demolished during the British colonial era. The Ramgarhia Bunga remains a symbol of the Ramgarhia Sikh community's identity, their historic sacrifices and contribution to defending the Golden Temple over the centuries.[89]

The Clock Tower did not exist in the original version of the temple. In its location was a building, now called the "lost palace". The officials of the British India wanted to demolish the building after the Second Anglo-Sikh war and once they had annexed the Sikh Empire. The Sikhs opposed the demolition, but this opposition was ignored. In its place, the clock tower was added. The clock tower was designed by John Gordon in a Gothic cathedral style with red bricks. The clock tower construction started in 1862 and was completed in 1874. The tower was demolished by the Sikh community about 70 years later. In its place, a new entrance was constructed with a design more harmonious with the Temple. This entrance on the north side has a clock, houses a museum on its upper floor, and it continues to be called ghanta ghar deori.[86][90]

Ber trees

The Golden Temple complex originally was open and had numerous trees around the pool. It is now a walled, two-storey courtyard with four entrances, that preserve three Ber trees (jujube). One of them is to the right of the main ghanta ghar deori entrance with the clock, and it is called the Ber Baba Buddha. It is believed in the Sikh tradition to be the tree where Baba Buddha sat to supervise the construction of the pool and first temple.[34][35]

A second tree is called Laachi Ber, believed to the one under which Guru Arjan rested while the temple was being built.[35] The third one is called Dukh Bhanjani Ber, located on the other side of the sanctum, across the pool. It is believed in the Sikh tradition that this tree was the location where a Sikh was cured of his leprosy after taking a dip in the pool, giving the tree the epithet of "suffering remover".[18][91] There is a small Gurdwara underneath the tree.[35] The Ath Sath Tirath, or the spot equivalent to 68 pilgrimages, is in the shade underneath the Dukh Bhanjani Ber tree. Sikh devotees, states Charles Townsend, believe that bathing in the pool near this spot delivers the same fruits as a visit to 68 pilgrimage places in India.[35]

Sikh history museums

The main ghanta ghari deori north entrance has a Sikh history museum on the first floor, according to the Sikh tradition. The display shows various paintings, of gurus and martyrs, many narrating the persecution of Sikhs over their history, as well as historical items such as swords, kartar, comb, chakkars.[92] A new underground museum near the clock tower, but outside the temple courtyard also shows Sikh history.[93][94] According to Louis E. Fenech, the display does not present the parallel traditions of Sikhism and is partly ahistorical such as a headless body continuing to fight, but a significant artwork and reflects the general trend in Sikhism of presenting their history to be one of persecution, martyrdoms and bravery in wars.[95]

The main entrance to the Gurdwara has many memorial plaques that commemorate past Sikh historical events, saints and martyrs, contributions of Ranjit Singh, as well as commemorative inscriptions of all the Sikh soldiers who died fighting in the two World Wars and the various Indo-Pakistan wars.[96]

Guru Ram Das Langar

Harmandir Sahib complex has a Langar, a community-run free kitchen and dining hall. It is attached to the east side of the courtyard near the Dukh Bhanjani Ber, outside of the entrance. Food is served here to all visitors who want it, regardless of faith, gender or economic background. Vegetarian food is served and all people eat together as equals. Everyone sits on the floor in rows, which is called sangat. The meal is served by volunteers as part of their kar seva ethos.[35]

Daily ceremonies

There are several rites performed everyday in the Golden Temple as per the historic Sikh tradition. These rites treat the scripture as a living person, a Guru out of respect. They include:[97][98]

- Closing rite called sukhasan (sukh means "comfort or rest", asan means "position"). At night, after a series of devotional kirtans and three part ardās, the Guru Granth Sahib is closed, carried on the head, placed into and then carried in a flower decorated, pillow-bed palki (palanquin), with chanting. Its bedroom is in the Akal Takht, on the first floor. Once it arrives there, the scripture is tucked into a bed.[97][98]

- Opening rite called prakash which means "light". About dawn everyday, the Guru Granth Sahib is taken out its bedroom, carried on the head, placed and carried in a flower-decorated palki with chanting and bugle sounding across the causeway. It is brought to the sanctum. Then after ritual singing of a series of Var Asa kirtans and ardas, a random page is opened. This is the mukhwak of the day, it is read out loud, and then written out for the pilgrims to read over that day.[97][98]

Influence on contemporary era Sikhism

Singh Sabha movement

The Singh Sabha movement was a late-19th century movement within the Sikh community to rejuvenate and reform Sikhism at a time when Christian, Hindu and Muslim proselytizers were actively campaigning to convert Sikhs to their religion.[99][100] The movement was triggered by the conversion of Ranjit Singh's son Duleep Singh and other well-known people to Christianity. Started in 1870s, the Singh Sabha movement's aims were to propagate the true Sikh religion, restore and reform Sikhism to bring back into the Sikh fold the apostates who had left Sikhism.[99][101][102] There were three main groups with different viewpoints and approaches, of which the Tat Khalsa group had become dominant by the early 1880s.[103][104] Before 1905, the Golden Temple had Brahmin priests, idols and images for at least a century, attracting pious Sikhs and Hindus.[105] In 1890s, these idols and practices came under attack from reformist Sikhs.[105] In 1905, with the campaign of the Tat Khalsa, these idols and images were removed from the Golden Temple.[106][107] The Singh Sabha movement brought the Khalsa back to the fore of Gurdwara administration[108] over the mahants (priests) class,[109] who had taken over control of the main gurdwaras and other institutions vacated by the Khalsa in their fight for survival against the Mughals during the 18th century[110] and had been most prominent during the 19th century.[110]

Jallianwala Bagh massacre

As per tradition, the Sikhs gathered in the Golden Temple to celebrate the festival of Baisakhi in 1919. After their visit, many walked over to the Jallianwala Bagh next to it to listen to speakers protesting the Rowlatt Act and other policies implemented by the British colonial government. A large crowd had gathered, when Colonel Reginald Edward Harry Dyer ordered a detachment of ninety soldiers (drawn from the 9th Gorkha Rifles and the 59th Scinde Rifles) under his command to surround the Jallianwala Bagh, and then open fire into the crowd. 379 were killed and thousands were wounded in the massacre.[111] The massacre strengthened the opposition to colonial rule throughout India, particularly that from Sikhs. It triggered massive non-violent protests. The protests pressured the British colonial government to transfer the control over the management and treasury of the Golden Temple to an elected organisation called Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC). The SGPC continues to manage the Golden Temple.[112]

Punjabi Suba movement

The Punjabi Suba movement was a long-drawn political agitation, launched by the Sikhs, demanding the creation of a Punjabi Suba, or Punjabi-speaking state, in the post-independence state of East Punjab.[113] It was first presented as a policy position in April 1948 by the Shiromani Akali Dal,[114] after the States Reorganization Commission set up after independence was not effective in the north of the country during its work to delineate states on a linguistic basis.[115] The Golden Temple complex was the main centre of operations of the movement,[116] and important events during the movement that occurred at the gurdwara included the 1955 raid by the government to quash the movement, and the subsequent Amritsar Convention in 1955 to convey Sikh sentiments to the central government.[117] The complex was also the site of speeches, demonstrations, and mass arrests,[116] and where leaders of the movement domiciled in huts during hunger strikes.[118] The borders of the modern state of Punjab, along with the official status of the state's native language of Punjabi in the Gurmukhi script, are the result of the movement, which culminated in the setting of the current borders in 1966.[119]

Operation Blue Star

The Golden Temple and Akal Takht were occupied by various militant groups in the early 1980s. These included the Dharam Yudh Morcha led by Sikh fundamentalist Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the Babbar Khalsa, the AISSF and the National Council of Khalistan.[120] In December 1983, the Sikh political party Akali Dal's President Harchand Singh Longowal had invited Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale to take up residence in Golden Temple Complex.[121] The Bhindranwale-led group under the military leadership of General Shabeg Singh had begun to build bunkers and observations posts in and around the Golden Temple.[122] They organised the armed militants present at the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar in June 1984. The Golden Temple became a place for weapons training for the militants.[120] Shabeg Singh's military expertise is credited with the creation of effective defences of the Gurdwara Complex that made the possibility of a commando operation on foot impossible. Supporters of this militant movement circulated maps showing parts of northwest India, north Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan as historic and future boundaries of the Khalsa Sikhs, with varying claims in different maps.[123]

In June 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to begin Operation Blue Star against the militants.[120] The operation caused severe damage and destroyed the Akal Takht. Numerous soldiers, militants and civilians died in the crossfire, with official estimates of death of 492 civilians and 83 Indian army men.[124] Within days of the Operation Bluestar, some 2,000 Sikh soldiers in India mutinied and attempted to reach Amritsar to liberate the Golden Temple.[120] Within six months, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi's Sikh bodyguards assassinated her.

In 1986, Indira Gandhi's son and the next Prime Minister of India Rajiv Gandhi ordered repairs to the Akal Takht Sahib. These repairs were removed and Sikhs rebuilt the Akal Takht Sahib in 1999.[125]

List of granthi

Granthi is a person, female or male, of the Sikh religion who is a ceremonial reader of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, which is the Holy Book in Sikhism. Here is list of granthi:

- Baba Buddha

- Bidhi Chand

- Mani Singh

- Gopal Das Udasi

- Chanchal Singh

- Atma Singh

- Sham Singh

- Jass Singh

- Jawahar Singh

- Harnam Singh

- Fateh Singh

- Kartar Singh kalaswalia

- Mool Singh

- Bhulinder Singh

- Chet Singh

- Makhan Singh

- Labh Singh

- Takur Singh

- Achhru Singh

- Arjan Singh

- Kapoor Singh

- Niranjan Singh

- Mani Singh

- Kirpal Singh

- Sahib Singh

- Pritam Singh

| Portrait | Name | Term Start | Term End | Appointed by | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhai Mani Singh | Head Granthi: 1 Vaisakh 1755 (Bikrami), 1698 AD | 1734 | Guru Gobind Singh | ||

| Bhai Surat Singh | 1761 | ||||

| Bhai Gurdas Singh | |||||

| Bhai Sant Singh | 1790 | 1832 | |||

| Giani Harnam Singh | 1885 | ||||

| Giani Fateh Singh | 1925 | ||||

| Giani Kartar Singh Kalaswalia | 1925

Head Granthi: 1929 |

1937 | |||

| Giani Labh Singh | 1926

Head Granthi: 1937 |

1 October 1940 | |||

| Giani Thakur Singh | 1927 | 1943 | |||

| Mahant Giani Mool Singh | 1934

Head Granthi: 1 October 1940 |

1952 | |||

| Giani Achhar Singh | 1940

Head Granthi: 23 May 1955 |

1962 | |||

| Giani Chet Singh | 1944

Head Granthi: 10 February 1963 |

31 May 1974 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Bhupinder Singh | 1948

Head Granthi: 1952 |

October 1963 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Arjan Singh | 1952 | 1957 | |||

| Giani Kirpal Singh | 2 April 1958

Head Granthi: 2 June 1974 |

16 April 1983 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Kapur Singh | 10 February 1963 | 3 September 1973 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Sohan Singh | 3 December 1966

Head Granthi: 30 May 1988 |

25 July 1988 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Niranjan Singh | 2 April 1974 | 16 March 1976 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Jasbir Singh | 2 April 1974 | 27 February 1976 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Mani SIngh | 2 June 1974 | 8 April 1983 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Sahib SIngh | 1 May 1976

Head Granthi: 16 April 1983 |

24 December 1986

Head Granthi: 26 January 1986 |

SGPC | ||

| Giani Mohan Singh | August 1978

Head Granthi: 29 July 1988 |

8 December 2000 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Puran Singh | 19 April 1983 Head Granthi: 26 January 1987 | 2 May 1988

Head Granthi: 1 May 1988 |

Sarbat Khalsa | ||

| Giani Jaswant Singh Parwana | 4 May 1985 | 1987 | |||

| Pandit Giani Bakhshish Singh | 26 January 1986 | Sarbat Khalsa | |||

| Baba Ram Singh | 6 March 1987 | 29 April 1998 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Pritam Singh | 10 August 1988 | SGPC | |||

| Giani Jagtar Singh Jachak | 29 November 1988 | 31 January 1989 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Joginder Singh Vedanti | 13 May 1989 | 30 April 1998 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Charan Singh | 29 November 1989 | 14 March 2001 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Puran Singh (Second Term) | 21 November 1990 | 28 March 2000 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Joginder Singh Vedanti (Second Term) | 22 May 1999 | SGPC | |||

| Giani Puran Singh

(Third Term) |

Head Granthi: 9 December 2000 | 14 January 2005 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Jaswinder Singh | 15 March 2001 | 9 April 2015 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Jagtar Singh | 15 March 2001 | 22 November 2022 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Mal Singh | 4 November 2001

Head Granthi: 18 November 2012 |

22 August 2013 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Jaswant Singh (Manji Sahib) | 31 May 2002 | 2009 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Mohan Singh (Second Term) | Additional: 1 February 2004 | 18 July 2004 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Mohan Singh (Third Term) | Additional:

20 July 2004 |

25 July 2009 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Maan Singh | 1 March 2009 | 9 June 2021 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Sukhjinder Singh | 1 March 2009 | 7 October 2020 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Ravail Singh | 1 March 2009 | 2017 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Jagtar Singh Ludhiana | 7 July 2011

Additional: 20 August 2013 Head Granthi: 22 November 2022 |

30 June 2023 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Raghbir Singh | 21 April 2014 | 24 August 2017 | SGPC | ||

| Giani Amarjeet Singh | 21 April 2014

Additional: 3 July 2023 |

Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Gurminder Singh | 21 April 2014 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Balwinder Singh | 21 April 2014 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Sultan Singh | 26 August 2021 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Rajdeep Singh | 26 August 2021 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Baljit Singh | 26 August 2021 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Raghbir Singh

(Second Term) |

Additional: 10 March 2023

Head Granthi: 30 June 2023 |

Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Kewal Singh | 15 July 2024 | Incumbent | SGPC | ||

| Giani Parwinderpal Singh | 15 July 2024 | Incumbent | SGPC |

Commemorative Postal Stamps

Commemorative stamps released by India Post (by year) –

See also

- Golden Temple, Vellore

- Amritsar Jamnagar Expressway

- Amritsar Ring Road

- Delhi Amritsar Katra Expressway

- Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib

- Hazur Sahib Nanded

- List of Gurudwaras

- Takht Sri Patna Sahib

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 41–42.

- ^ McLeod, W.H. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 978-1442236011. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

The latter name was attached to it after Maharaja Ranjit Singh gilded the upper two stories, and it became known as the Suvaran Mandir, or the Golden Temple

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kerr, Ian J. (2011). "Harimandar". In Harbans Singh (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala. pp. 239–248. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Eleanor Nesbitt 2016, pp. 64–65, 150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Harmandir-Sahib". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2014. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ a b Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 33.

- ^ a b Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 5–7.

- ^ a b W. Owen Cole 2004, p. 7

- ^ a b M. L. Runion (2017). The History of Afghanistan, 2nd Edition. Greenwood. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018., Quote: "Ahmad Durrani was forced to return to India and [he] declared a jihad, known as an Islamic holy war, against the Marathas. A multitude of tribes heralded the call of the holy war, which included the various Pashtun tribes, the Balochs, the Tajiks, and also the Muslim population residing in India. Led by Ahmad Durrani, the tribes joined the religious quest and returned to India (...) The domination and control of the [Afghan] empire began to loosen in 1762 when Ahmad Shah Durrani crossed Afghanistan to subdue the Sikhs, followers of an indigenous monotheistic religion of India found in the 16th century by Guru Nanak. (...) Ahmad Shah greatly desired to subdue the Sikhs, and his army attacked and gained control of the Sikh's holy city of Amritsar, where he brutally massacred thousands of Sikh followers. Not only did he viciously demolish the sacred temples and buildings, but he ordered these holy places to be covered with cow's blood as an insult and desecration of their religion (...)"

- ^ a b c Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson & Paul Schellinger 2012, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Eleanor Nesbitt 2016, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Jean Marie Lafont (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ^ Fenech, Louis E. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. OUP Oxford. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

But this strategy backfired in the spring of 1984, when a group of armed radicals led by Bhindranwale decided to provoke a confrontation with the government by occupying Akal Takhat building inside the Golden Temple complex.

- ^ "Nature and importance of Harmandir Sahib – Pilgrimage". BBC (GCSE Religious Studies Revision ed.). Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Soon, Golden Temple to use phone jammers". The Times of India. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ Sri Harimandir Sahib, Amritsar, Punjab Archived 16 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- ^ Asher, Catherine Blanshard (1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

Situated in the middle of an enormous tank connected to land via a long causeway, the shrine is known as Harimandir.

- ^ a b Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 146.

- ^ McLeod, W.H. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 269. ISBN 978-1442236011.

- ^ Henry Walker 2002, pp. 95–98.

- ^ H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Hemkunt Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- ^ a b c G.S. Mansukhani. "Encyclopaedia of Sikhism". Punjab University Patiala. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b Christopher Shackle & Arvind Mandair 2013, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ W. H. McLeod 1990, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Mahindara Siṅgha Joshī (1994). Guru Arjan Dev. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-81-7201-769-9.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 205.

- ^ Rishi Singh (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. Sage Publications India. ISBN 978-9351505044. It is, however, possible that Mian Mir, who had close links to Guru Arjan, was invited and present at the time of the laying of the foundation stone, even if he did not lay the foundation stone himself.

- ^ Rishi Singh (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. Sage Publications India. ISBN 978-9351505044.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh 2011, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Madanjit Kaur (1983). The Golden Temple: Past and Present. Amritsar: Dept. of Guru Nanak Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University Press. p. 174. OCLC 18867609. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ a b c W. Owen Cole 2004, pp. 6–9

- ^ a b c d e f Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 435–436.

- ^ a b Pashaura Singh (2005). "Understanding the Martyrdom of Guru Arjan" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 12 (1): 29–62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b W. H. McLeod (2009). "Arjan's Death". The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0810863446. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

The Mughal rulers of Punjab were evidently concerned with the growth of the Panth, and in 1605 the Emperor Jahangir made an entry in his memoirs, the Tuzuk-i-Jahāṅgīrī, concerning Guru Arjan's support for his rebellious son Khusrau Mirza. Too many people, he wrote, were being persuaded by his teachings, and if the Guru would not become a Muslim the Panth had to be extinguished. Jahangir believed that Guru Arjan was a Hindu who pretended to be a saint and that he had been thinking of forcing Guru Arjan to convert to Islam or his false trade should be eliminated, for a long time. Mughal authorities seem to have been responsible for Arjan's death in custody in Lahore, and this may be accepted as an established fact. Whether the death was by execution, the result of torture, or drowning in the Ravi River remains unresolved. For Sikhs, Guru Arjan Dev is the first martyr Guru.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech, Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition, Oxford University Press, pp. 118–121

- ^ a b c Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Syan 2014, p. 176.

- ^ W. H. McLeod (2005). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Scarecrow. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-8108-5088-0.

- ^ Harbans Singh (1992–1998). The encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 3. Patiala: Punjabi University. p. 88. ISBN 0-8364-2883-8. OCLC 29703420. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt Kang, Kanwarjit Singh (1988). "13. Art and Architecture of the Golden Temple". Punjab Art and Culture. Atma Ram & Sons. pp. 56–62. ISBN 9788170430964.

- ^ Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 22–25.

- ^ a b c d e f Bakshi, Artika Aurora; Dhillon, Ganeev Kaur. "The Mural Arts of Panjab". Nishaan Nagaara Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Singh, Harbans (2011). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism Volume II E-L (3rd ed.). Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-81-7380-204-1.

- ^ Gupta, Hari (2007). History Of The Sikhs Vol. II Evolution Of Sikh Confederacies (1707–69). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 216. ISBN 978-81-215-0248-1.

- ^ Patwant Singh (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen. pp. 18, 177. ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ "Maharaja Ranjit Singh's contributions to Harimandir Sahib". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Pandharipande, Reeti; Nadimpally, Lasya (5 August 2017). "A Brief History of The Nizams of Hyderabad". Outlook Traveller. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Nama, Khalsa (8 March 2024). "The Origins of the Giani Samprada: Giani Surat Singh". The Khalsa Chronicle. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "The Kapurs, including Bhai Jawahir Singh Kapur" (PDF).

- ^ Swami, Praveen (16 January 2014). "RAW chief consulted MI6 in build-up to Operation Bluestar". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839–2004, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 332.

- ^ a b "Operation Blue Star: India's first tryst with militant extremism". DNA. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Sikh Leader in Punjab Accord Assassinated". LA Times. Times Wire Services. 21 August 1985. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

The Punjab violence reached a peak in June, 1984, when the army attacked the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the holiest Sikh shrine, killing hundreds of Sikh militants who lived in the temple complex, and who the government said had turned it into an armory for Sikh terrorism.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A., ed. (2009). "India". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Kiessling, Hein (2016). Faith, Unity, Discipline: The Inter-Service-Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1849048637. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Varinder Walia (20 March 2007). "Army reveals startling facts on Bluestar". Tribune India. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ White Paper on the Punjab Agitation. Shiromani Akali Dal and Government of India. 1984. p. 169. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Kiss, Peter A. (2014). Winning Wars amongst the People: Case Studies in Asymmetric Conflict (Illustrated ed.). Potomac Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-1612347004. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Hamlyn, Michael (12 June 1984). "Amritsar witness puts death toll at 1000". The Times. p. 7.

- ^ Eric Silver (7 June 1984). "Golden Temple Sikhs Surrender". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Chellaney, Brahma (14 June 1984). "Sikhs in Amritsar 'tied up and shot'". The Times.

- ^ "India is set to drop prosecution of AP reporter in Punjab Case". The New York Times. Associated Press. 14 September 1985. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Indian Police Question Reporter on Amritsar". The New York Times. Associated Press. 24 November 1984. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Westerlund, David (1996). Questioning The Secular State: The Worldwide Resurgence of Religion in Politics. C. Hurst & Co. p. 1276. ISBN 978-1-85065-241-0.

- ^ Sandhu, Kanwar (15 May 1990). "Sikh Army deserters are paying the price for their action". India Today. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Singh, Pritam (2008). Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-415-45666-1. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ "Five years on, govt yet to announce closure of Galliara Project : The Tribune India". Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "SGPC seeks control of Golden Temple galliara, heritage street". Hindustan Times. 31 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Golden Temple: Galiara haven for drug addicts, cops claim 'no info'". 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Nanhi Chhaan's Golden Temple 'galliara' upkeep contract ends : The Tribune India". Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Golden temple's galiara, a picture of complete neglect". Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023 – via PressReader.

- ^ Rana, Yudhvir (19 December 2021). "Amritsar: Youth disrupts religious service in Golden Temple". Times of India. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "National Security Guard team at Amritsar twin blast site". ANI News. 9 May 2023. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Eleanor Nesbitt 2016, pp. 64–65 Quote: "The Golden Temple (...) By 1776, the present structure, a harmonious blending of Mughal and Rajput (Islamic and Hindu) architectural styles was complete."

- ^ Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 97–116.

- ^ a b Gene R. Thursby (1992). The Sikhs. Brill. pp. 14–15. ISBN 90-04-09554-3.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2004). Sikhism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-1-4381-1779-9.

- ^ Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 68–73.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Geoffrey William Bromiley (1999). The encyclopedia of Christianity (Reprint ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14596-2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh 2011, p. 80.

- ^ Pashaura Singh; Norman Gerald Barrier; W. H. McLeod (2004). Sikhism and History. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–215. ISBN 978-0-19-566708-0.

- ^ W. Owen Cole 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b Ian Talbot (2016). A History of Modern South Asia: Politics, States, Diasporas. Yale University Press. pp. 80–81 with Figure 8. ISBN 978-0-300-19694-8.

- ^ Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, p. 435.

- ^ a b Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Pashaura Singh; Norman Gerald Barrier (1999). Sikh Identity: Continuity and Change. Manohar. p. 264. ISBN 978-81-7304-236-2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ Shikha Jain (2015). Yamini Narayanan (ed.). Religion and Urbanism: Reconceptualising Sustainable Cities for South Asia. Routledge. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-317-75542-5.

- ^ H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- ^ Bruce M. Sullivan (2015). Sacred Objects in Secular Spaces: Exhibiting Asian Religions in Museums. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-1-4725-9083-1.

- ^ "Golden Temple's hi-tech basement showcases Sikh history, ethos opens for pilgrims". Hindustan Times. 22 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ G. S. Paul (22 December 2016). "Golden Temple's story comes alive at its plaza". Tribune India. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech (2000). Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition: Playing the "game of Love". Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45, 57–61, 114–115, 157 with notes. ISBN 978-0-19-564947-5.

- ^ K Singh (1984). The Sikh Review, Volume 32, Issues 361–372. Sikh Cultural Centre. p. 114.

- ^ a b c Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh 2011, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c Kristina Myrvold (2016). The Death of Sacred Texts: Ritual Disposal and Renovation of Texts in World Religions. Routledge. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-1-317-03640-1.

- ^ a b Barrier, N. Gerald; Singh, Nazer (2002) [1998]. Singh, Harbans (ed.). Singh Sabha Movement (4th ed.). Patiala, Punjab: Punjab University. pp. 205–212. ISBN 978-8173803499. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Singh Sabha (Sikhism)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 28–29, 73–76.

- ^ Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 382–383. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ^ a b Kenneth W. Jones (1976). Arya Dharm: Hindu Consciousness in 19th-century Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-520-02920-0., Quote: "Brahmin priests and their idols had been associated with the Golden Temple for at least a century and had over these years received the patronage of pious Hindus and Sikhs. In the 1890s these practices came under increasing attack by reformist Sikhs."

- ^ W. H. McLeod (2009). "Idol Worship". The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- ^ Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 320–327. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ^ Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 542–543.

- ^ Deol, Harnik (2003). Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab. Routledge. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-1134635351. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed (illustrated ed.). London: A&C Black. p. 83. ISBN 978-1441102317. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Kristen Haar; Sewa Singh Kalsi (2009). Sikhism. Infobase Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4381-0647-2.

- ^ Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 433–434.

- ^ Doad 1997, p. 391.

- ^ Bal 1985, p. 419.

- ^ Doad 1997, p. 392.

- ^ a b Doad 1997, p. 397.

- ^ Bal 1985, p. 426.

- ^ Doad 1997, p. 398.

- ^ Doad 1997, p. 404.

- ^ a b c d Jugdep S Chima (2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. Sage Publications. pp. 85–95. ISBN 978-81-321-0538-1.

- ^ Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839–2004, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 337.

- ^ Tully, Mark (3 June 2014). "Wounds heal but another time bomb ticks away". Gunfire Over the Golden Temple. The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Brian Keith Axel (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. pp. 96–107. ISBN 0-8223-2615-9. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "What happened during 1984 Operation Blue Star?". India Today. 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Know facts about Harmandir Sahib, The Golden Temple". India TV. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

General bibliography

- Pardeep Singh Arshi (1989). The Golden Temple: history, art, and architecture. Harman. ISBN 978-81-85151-25-0.

- Bal, Sarjit Singh (1985). "Punjab After Independence (1947–1956)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 46: 416–430. JSTOR 44141382.

- W. Owen Cole (2004). Understanding Sikhism. Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-906716-91-2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Doad, Karnail Singh (1997). "Punjabi Sūbā Movement". In Siṅgh, Harbans (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Sikhism (3rd ed.). Patiala, Punjab, India: Punjab University, Patiala (published 2011). pp. 391–404. ISBN 9788173803499. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- W. H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.

- Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-45101-0. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-962-1.

- Henry Walker (2002). Kerry Brown (ed.). Sikh Art and Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-63136-0. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Syan, Hardip S. (2014). "Sectarian Works". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–179. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2019.