Geology of Victoria

Victoria is an Australian state, situated at the southern end of the Great Dividing Range. The Great Dividing Range stretches along the east coast of the continent and terminates near the Victorian city of Ballarat west of the capital Melbourne, though the nearby Grampians may be considered to be the final part of the range. The highest mountains in Victoria (just under 2,000 m) are the Victorian Alps, located in the northeast of the state.

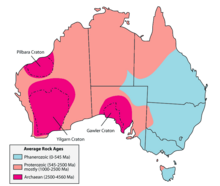

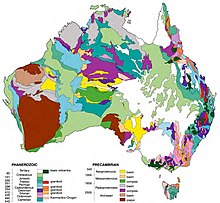

The northwest of the state is mostly Cainozoic rocks while the southeast is primarily made up of Palaeozoic rocks.[1] There have been no discoveries of Precambrian rocks in Victoria.

The low flat northwest of the state that borders the Murray River was once the bed of an ancient sea and the land is much afflicted with salinity. Saline drainage from Victorian land is one of the sources of the salinity problem in the Murray–Darling River system. Commercial salt evaporation is undertaken near Swan Hill.

Central and western Victoria comprise world-class vein-hosted gold deposits, hosted mostly in the extensive Ordovician turbidites.

The southeast of the state has enormous brown coal fields.[2]

Volcanism

There is an area of extensive volcanism in central and southwestern Victoria, where there are numerous volcanoes and volcanic lakes. The Western Victorian Volcanic Plains are the third largest in the world after the Deccan in western India, and the Snake River Plateau in Idaho, United States. The most recent volcanic activity was at Mt Eccles, which last erupted a few thousand years ago, making it an active volcanic region.[3] Large basaltic lava flows are present on the western side of Melbourne and in the southwest of the state.

Neoproterozoic to early Carboniferous

This period is covered by the recent Geological Survey of Victoria publication The Tasman Fold Belt System in Victoria. The sequence of events associated with the building of southeastern Australia reveals that mineralization and magmatic processes are intimately linked with the tectonic development of the region. The history is dominated by east–west compression of predominantly oceanic sedimentary and igneous rocks and their resultant folding, faulting and uplift. Recently, it has become increasingly apparent that major north–south movements have also been involved in constructing eastern Australia.

The Palaeozoic basement is traversed by thrust faults more or less parallel to the north–south structural grain. The largest faults separate rocks with different ages and structural histories, and subdivide Victoria into three main structural rankings consisting of twofold belts (Delamerian and Lachlan), two terranes in the Lachlan Fold Belt (Whitelaw and Benambra), and ten structural zones (Glenelg, Grampians-Stavely, Stawell, Bendigo, Melbourne, Tabberabbera, Omeo, Deddick, Kuark, Mallacoota).[4]

Moyston Fault

The Moyston Fault is the most important fault as it forms the terrane boundary between the Delamerian and Lachlan fold belts. These twofold belts show important differences. The Delamerian Fold Belt is mainly composed of Neoproterozoic-Cambrian rocks and was deformed in the Late Cambrian Delamerian Orogeny whereas the Lachlan Fold Belt contains mainly Cambrian-Devonian rocks with the main deformations occurring in the late Ordovician to early Carboniferous interval. The first regional deformation to affect the Lachlan Fold Belt was the Benambran Orogeny, about 450 MYA, after the Delamerian Orogeny.[4] Granites comprise 20% of the total exposed area of the Lachlan Fold Belt and fall within an age range of 440 to 350 MYA. Volcanics associated with the granites are also widespread and cover an additional 5%. Blocks of older crust consisting of Neoproterozoic-Cambrian rocks, such as the Selwyn Block in central Victoria, were deformed during the late Cambrian Tyennan Orogeny prior to being incorporated into the Lachlan Fold Belt.

Baragwanath Transform

The second major structural break in Victoria is the Baragwanath Transform, which occurs along the eastern side of the Selwyn Block. This transform fault divides the Lachlan Fold Belt into two terranes, the Whitelaw Terrane to the west and the Benambra Terrane to the east. The main difference between these is that orogen-parallel (north-south) transport was more prevalent in the Benambra Terrane, whereas convergent east–west transport orthogonal to the orogen was dominant in the Whitelaw Terrane.

See also

- List of Victorian volcanoes

- Geology of Australia

- Australian gold rushes

- Murray–Darling basin

- Murray–Darling Basin Authority

References

- ^ Macdonald, J. Reid; Mary Lee Macdonald; Patricia Vickers-Rich; Leaellyan S. V. Rich; Thomas H. Rich (1997). Fossil collectors guide. Kangaroo Press. p. 155. ISBN 086417845X.

- ^ "Coal". 13 May 2019.

- ^ "What is the difference between an active, erupting, dormant and extinct volcano?". www.volcanodiscovery.com.

- ^ a b Birch, W.D., ed. (2003). Geology of Victoria. Special Publication. Vol. 23. Geological Society of Australia (Victorian Division). ISBN 1876125330.

External links

- "Victoria's geology". Earth Resources. Dept. of Jobs Precincts & Regions, Victoria State Government. 2019.

- GeoVIC - Victorian Government Geospatial Application

- Victorian Geology

- Western Victorian Volcanic Plains